Chapter 12

Measuring and Managing Performance

Without targets you cannot measure achievements, deviations from stated objectives, or performance. There is a need for both quantitative and qualitative targets. A performance culture is rooted in defining objectives and creating a results-oriented approach. But it involves more than just looking at financial numbers. It also has to do with the type of delivery achieved and its quality. Measuring performance requires accountability in order to obtain a result that provides information about a given quality at a certain point in time. Resources that can be invested are finite. It is necessary, therefore, to take a structured approach to make best use of these limited resources. This mentality is important to ensure that people respect and invest the resources wisely within the time constraints available and from the standpoint of the company’s objectives. Once this process has been established, then and only then should performance be examined in terms of results and numbers.

UNDERSTANDING PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT

If performance management is neglected, the best-crafted strategies and visions will be to no avail. Even when a company has a credible vision, it will not achieve it if it cannot implement the steps to fulfil its goals. As discussed in Chapter 11, “Defining and Growing Leadership and Culture,” leading is about creating a credible vision. But it doesn’t stop there. Equally important is the execution, which has to be right. Performance management supplies the necessary link required to translate leadership’s vision into the very concrete actions involved in making it a reality.

Performance management can be applied to individual employees and entire companies. For employees, it can measure an individual’s performance and be used to set pay based on how he or she achieves targets and goals. For the business as a whole, performance management measures how well goals are achieved across the entire organisation or by divisions and teams. In all cases, goals—specific targets—must be aligned with the company’s priorities. If growth is targeted, this might relate to reaching specific revenue targets. If the aim is to become more competitive, it might be necessary to lower costs relative to peers and take measures to ensure a culture of innovation. If profit margins are to be expanded, this can be expressed by establishing precise targets.

Performance management can best be understood as the key to implementing strategy. Doing a good job of measuring performance is therefore at the heart of successful performance management. This chapter specifies which measurements are needed and how to assess the results. It is important to note that effective measurements need to go well beyond financial data. Relying on historical information alone is like trying to steer a car looking only in the rear view mirror. For companies, a focus on the past increases a risk that by the time some development is hurting the business to the degree that it is reflected in numbers, it is probably too late to offer a remedy. Similarly, positive developments that offer clues as to where future revenues can be obtained may be neglected unless close watch is kept on the factors truly driving performance. When only the “backward-looking” aspects are factored in, as is the case with most mainstream financial data, management’s view of the company’s ability to respond to future events is greatly restricted. This becomes clear especially during crises when businesses that were thought to be sound suddenly fail. It is much easier to hit targets in good markets. Performance management, therefore, is more in focus in poor markets. At such times, shortcomings may suddenly become glaringly apparent. Again, however, it will be too late to respond; that is why systems are needed to provide information about performance in a timely way, especially taking into account indicators that go beyond mainstream financial data.

In the context of performance management, information about and reporting by private banks is fairly straightforward; as a rule of thumb, assets under management provide about two-thirds of revenue, and employees generate about 70 percent of costs. The usual metrics include net new money (volume of inflows of client money minus volume of outflows), total client assets under management, costs relative to income, and profit margin (measured by net profit relative to assets under management). These metrics provide most of the information necessary to assess the growth and profitability of a private bank. But again, it is important to include those pieces of information that offer a sense of how business and trends might develop in the future. During the 2008 financial crisis, it is fair to say that if banks had been more aware of the changes that would affect their business, more questions would have been raised about their own viability. Questions also would have been asked about the type of behaviour encouraged and rewarded by performance-related compensation. For any company, but especially banks, rethinking how performance is measured and managed is required on a continual basis.

The following paragraphs examine general measures suited to evaluating performance, before taking a closer look at ways in which private banks specifically can use the information about their current business to be more proactive, rather than waiting until it is too late. In particular, the so-called balanced scorecard approach can deliver a sensible and fairly simple way to take into account major aspects of the business to deliver a bigger picture. It is also important especially for banks seeking to encourage a culture focused on “excellence,” as opposed to one where the only measures that are taken into account are financial targets.

THE EVOLUTION OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

Even when a company has the best people and its strategy is sound, it can still falter. Often it may come down to just one single factor that makes the difference—execution of strategy. Even competent and talented CEOs who fail to get things done can stumble in this regard. According to a widely cited study published in Fortune, in an estimated 70 percent of the cases where a CEO failed, it was caused by poor execution.(1) This book has covered many strategy-related concepts and themes that are important in creating a culture of excellence. But to get there, real hands-on tasks must be accomplished.

In companies with a simple organisation, especially smaller companies run by the founder, those at the top of the executive chain stay in close touch with most of the business through direct contacts with employees and customers. As an organisation grows, this type of control becomes more difficult. Many methods may be introduced in an attempt to regain the intuitive interaction that formed the basis of oversight when the company was smaller and simpler. Any business prepared to collect enough information can deliver just about every imaginable parameter in real time to the CEO or other decision makers. But as the financial crisis of 2008 proved, monitoring data is not the same as actually managing performance to achieve sustainable growth.

FROM MODELS TO STRATEGY TO METRICS

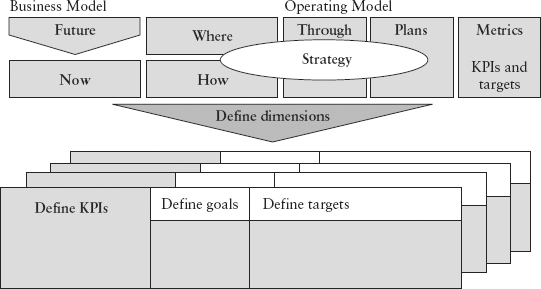

Performance management originated in industrial manufacturing. But as larger companies grew more prevalent, metrics have been adapted to suit service providers, including banks. For financial firms, the business model should define what a bank does to generate revenues through its client value proposition. This takes into account the products and services for which the customer pays. Success is defined by the extent to which the customer’s needs are met. According to this view, the operating model is a separate and distinct set of measures applied to functions needed to support, control, and manage delivery of products and services that comprise the customer value proposition. These measures define how the bank creates value for its stakeholders.

It will be the strategy that determines how the business operations and processes are carried out. The performance management system, however, provides the vital link between the strategy as it is envisioned and how it is implemented in the real world. The process to set up an effective system begins with defining the performance to be assessed and determining which aspects here are most relevant. For each it is then important to choose what will be measured. It is now time to close the circle and return to the first chapter of this book. The chart that follows is similar to the one presented in Chapter 1, “A Framework for Excellence in Private Banking.” This time, however, the key performance indicators, specific goals, and targets are added, as shown in Figure 12.1.

THE PERFORMANCE CYCLE

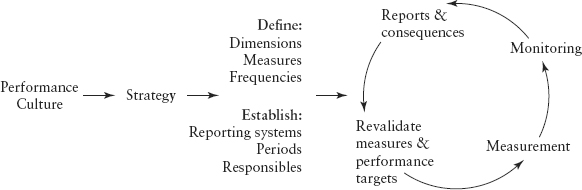

The performance cycle is a process designed to allow a company to improve the offering to the customer or client as well as its own earnings. Figure 12.2 shows a type of performance cycle. The first step is to define the main perimeters essential to the measurements, as well as the precise things to be measured. In addition, the frequency must be determined—in other words, how often are measurements to be taken? Systems to gather and report data are needed. Responsibilities must be assigned for judging different parts of the process. Once these initial steps have been completed, the cycle becomes self-perpetuating. Conclusions can be drawn and actions taken at an appropriate point. These might include readjusting the measures and performance targets or revalidating them, providing they are still appropriate. Then the necessary changes can be introduced in terms of either the people involved or the processes themselves.

The annual budgeting process is an example of a performance cycle. It tends to be fairly ineffective as a performance management tool. Too often companies’ budget processes are dominated by factors that go beyond financial figures. Furthermore, relying on a budget alone means that performance management is focused solely on financials, when in fact other dimensions are needed. In addition, the annual budget and the annual financial report take into account only past performance. Performance management, however, requires timely data that will allow a company to intervene preemptively. The best that can be achieved is gathering as much relevant information as possible about the current situation. This means choosing categories that can be monitored in real time, or at least on a weekly basis, in addition to those that should be monitored monthly or at least quarterly.

DIMENSIONS OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

The importance of assessing performance on many different levels was highlighted in a 1992 study by Harvard professor Robert Kaplan and technology consultant David Norton.(2) Their approach was based on a year-long research project involving 12 companies considered at the time to be on the leading edge of performance measurement. According to their results, information needed to make a complete assessment of a business goes beyond financial measures. It also requires those considered predictive, such as customer satisfaction. They advocated assigning equal weights to different aspects of performance measurement, thus creating the idea of a “balanced” scorecard. The approach can be compared to instruments in an airplane cockpit. Each offers a separate set of information. All readings are essential and require constant monitoring. Companies pay attention to all types of information. Kaplan and Norton advocated using four main “dimensions”: customers; internal perspective; innovation; and how, on the outside, shareholders perceive the company. Financial data are just part of the picture. These can provide an historical perspective on performance, but other factors are needed.

Which diagnostic tools are needed to make a valid assessment? In 1995, American economist Peter F. Drucker published a paper entitled “The Information Executives Truly Need.”(3) His study highlighted the fact that advances in technology are forcing companies to see their businesses in a new light. Drucker, who had witnessed firsthand the rise of global industry in the first half of the 20th century as well as the advances in technology in the 1980s and 1990s, challenged the idea that big companies were truly “profitable” even though, based on conventional accounting methods, they appeared to be. He advocated moving from traditional cost accounting to activity-based accounting, which includes the cost of all resources—including the cost of capital—to determine whether or not a business creates wealth. Gaining a clear understanding of profitability requires questioning not just the cost of processes but the notion that all processes are as efficient as possible. It may involve deciding whether all the processes are even necessary. This is especially key for service industries, including banking, where it is hard to separate different strands of “production.” Thinking along such lines forces these companies to see that ultimately there is just one activity at the centre of costs and results—serving the customer. It is the yield per customer that determines the true profitability of the business.

Drucker further advocated managing by objectives—allowing leaders and subordinates to agree on goals and then letting subordinates figure out how best to achieve them. His management by objectives (MBO) approach is viewed as the antithesis to “management by control.” To achieve it businesses need to employ a variety of indicators to gain a full picture and to set targets. This should allow them to create genuine value. The four diagnostic tools outlined by Drucker are as follows:

DEFINING THE METRICS

Having defined the dimensions to be considered when evaluating performance, the next task is to select the performance measures or metrics. The challenge is to find manageable sets of measures appropriate to each task.

Measurement and Monitoring, Reports and Consequences

When designing the measuring and reporting system, it is important to define who is responsible for reporting, what form the reports should take, how often the reports are made, and the level of detail required.

Measuring and monitoring are routine steps in any performance cycle. During this process, teams or individuals receive early warning signals or get interim encouragement. This information can be presented along with an assessment of the probability of meeting specific targets.

The goal of performance management should be to direct behaviour to ensure the implementation of the strategy. Implementing strategies always involves a process of change within an organisation. Experts on change management typically agree that human behaviour is hard to alter unless consequences are involved. Based on that, risk of failure must be made clear and the right behaviour acknowledged and rewarded.

Alongside monitoring individual performance, an effective system to manage performance requires reporting at predefined intervals, accompanied by regular appraisal and discussion of necessary actions. Normally there are predetermined ranges considered acceptable for each measure.

The Role of Benchmarks

Benchmarking is the process of identifying best practices and top performers and using them as a reference for company or individual performance. Benchmarking offers a quick and easy way to assess performance and identify areas of strengths and weaknesses. It can be applied to competitors or peers.

There is a danger if a company becomes preoccupied with competition. A company fixated on rivals might fail to recognize opportunities beyond its day-to-day businesses. One way to resolve this is to make competition effectively irrelevant. In the book Blue Ocean Strategy by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, the authors advocate looking for opportunities beyond the turbulent “red” waters where competitors, like sharks, feed on smaller prey. Instead, they advise companies to seek out “blue oceans” where competition is minimal or nonexistent.(4)

PRIVATE BANKING AND PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, it is not enough to simply look at the financial metrics of an organisation when measuring performance. By the time these pieces of information show meaningful developments it is often too late to react to trends and developments. This is true for private banks as well. Problems are likely to show up first in areas such as client satisfaction, innovation achieved, and so on before they are ever reflected in the financial figures.

In private banking, where employee compensation constitutes 70 percent of the cost base, business performance depends largely on the performance of individuals. Managing performance can thus be viewed to a large degree as managing the performance of individuals. Improving performance takes time. During weak market phases especially, it is very hard to increase income, so much of the emphasis is placed on lowering operating expenses. Assessing individual performance also depends in part on what role the individual plays. For example, a team head needs to ensure the success of relationship managers through coaching and mentoring. Accordingly, his or her performance measures should emphasise these aspects of learning and growth or related internal processes. A relationship manager’s performance should be measured by client satisfaction, which may be a factor in increasing net new money or increasing the profitability of those assets already managed. There are two ways to measure whether targets are being met, based on discretionary or non-discretionary factors. Discretionary performance measurements are based on subjective assessments. Non-discretionary performance mostly is expressed in numbers derived from clear formulas or figures that are directly related to a business process. In private banking, this latter measure often includes net new money or assets under management.

In private banking, a key indicator used to evaluate the performance of a relationship manager is net new money, expressed as a percentage of current assets under management. The ratio of new money to existing money makes it clear whether the relationship manager is struggling with acquisitions, losing business, or bringing in new business. In terms of accounts, it is more effective for a team head to look at how many accounts have been opened and closed, or net new money, rather than looking only at assets under management in order to gain more insight regarding future trends in this area. Fluctuations in assets under management, at least in the short run, are more likely to be related to market performance than the performance of the bank. Yet even here, a single metric tells only part of the story. A holistic approach is required. Using the balanced scorecard already described in this chapter makes sense. It can be viewed as a tree; clients and financials might be compared to the foliage and fruit, which flourish only when the soil (innovation and competencies of employees), as well as the trunk and root system (processes) are healthy.

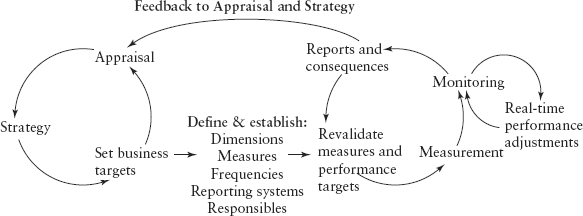

When put into practice in private banking, the feedback loop shown in Figure 12.3 must link performance of an individual relationship manager or division to the overall strategy. If a relationship manager completely fails to reach the defined targets, the organisation should consider that person’s individual situation and should appraise the way the business case was evaluated and what assumptions were made about the market. Were the indicators used during the recruitment process disregarded? What specific market (i.e., geographic region and whether it is a growth market or a consolidating market), or client segment is the relationship manager targeting? Are the difficulties encountered a sign of some larger and more problematic trend ahead? These questions can provide important insights. Used actively, they might even encourage learning and growth across the entire organisation. For example, if a department is not achieving its referral targets or is not ranking high in terms of what is called in the business “market purity,”* a bank might need to reconsider the underlying assumptions about synergies rather than simply try to remedy the problem by putting pressure on the teams involved.

Rewards must be included in the performance cycle. The widespread focus on compensation in the financial industry and regulatory recommendations, including those in Switzerland, could place limits on the scope of discretionary performance-related compensation allowed. But positive incentives provide a foundation for outstanding performance. Nonfinancial incentives, such as those discussed in Chapter 10, “Winning the War for Talent,” may play a major role here as well. There are several ways for nonfinancial incentives to be used to drive performance. For example, relationship managers who achieve an outstanding performance can be singled out and invited to speak at events or during training to share tips and offer examples of best practice. This also caters to higher-level human needs.

With regard to the overall business of private banking, based on the categories described, the most important questions to gain a clear view of performance might be some of the following:

Applied to internal “competitors” or peers, benchmarking can be useful in setting a bar based on the performance of the top relationship managers, using them as a standard by which to measure others in the team or division. The advantage of this approach is that comparisons can be made based on a level playing field; each relationship manager is operating in the same environment with the same products and services and support systems. The remaining variables are each individual relationship manager’s target segment, personal network, and, finally, personal performance.

Another area pertains to products. Some banks fix sales targets for in-house products. Sales of such products by relationship managers are then tracked. At best, this is a questionable practice. It contradicts the core value proposition of offering clients uniquely tailored custom solutions. When sales figures tied to specific products are used as performance measures, a conflict of interest can arise between the short-term goal of selling more products and the desire to achieve long-term client satisfaction. It is in the best long-term interest of a private bank, where fully two-thirds of the revenue is derived from assets under management, to avoid angering clients. As long as assets remain stable, they can serve as a good forecaster. So the challenge is not what is to be done, but what should not be done. The first rule is thus to not annoy or disappoint the client. In that sense, performance management might be viewed in a different light. Aggressive sales tactics that in theory might momentarily bolster revenues will, in the long run, unsettle clients, especially if the product performance disappoints. This will do more harm than good.

For a private bank, it is relatively easy to identify the relevant key performance indicators and the factors driving them. Private banks face a major challenge during periods when markets suffer shocks and setbacks, leading clients to be more conservative and retreat to defensive cash positions. It is extremely important in such periods to ensure that the bank is running lean and efficient operations, especially in service and support functions. Beyond that, banks need to focus on better risk management and compliance throughout the entire business. It becomes even more important to monitor signals so as to position the business to be responsive to changes in markets, the competitive landscape, and client needs.

To summarise, it is vital for measurements to be centred around realistic goals based on a concrete strategy. It is essential to have sound information upon which to base a strategy. International businesses plans, for example, need to be based on in-depth local know-how, as opposed to the global wealth reports of consulting firms. And especially in private banking, the industry should not dogmatically adhere to a two-year break-even period. Private banks operate in an industry characterised by long-term developments. Those in the business must have the courage to be honest. That includes being able to say when an investment will likely need a longer period to break even. It is also important to realise that forward-looking indicators are very important. If only “hard” financial metrics are used, such as assets under management, by the time these detect that something is amiss in terms of net new money flows, it is already late in the game and the brand will come under pressure. It is far better to address problems before they reach this stage.

CHOOSING WHAT TO MEASURE

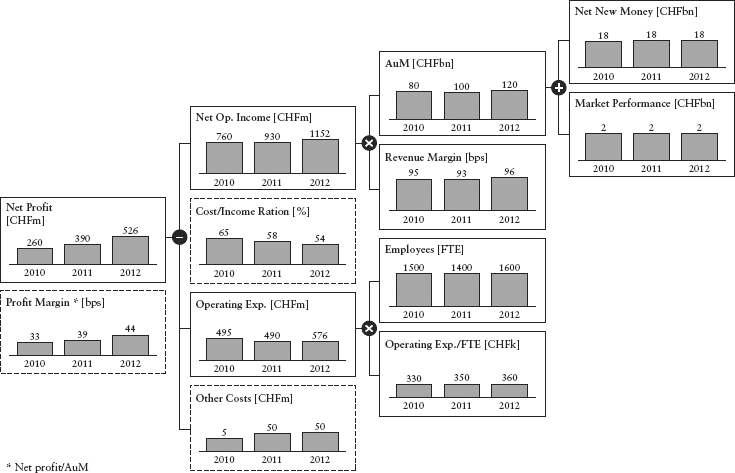

In private banking, net new money, assets under management, and return on assets are the key performance measures. Figure 12.4 provides a schematic overview of the interdependencies among private banking’s key measures.

Looking at net new money one can say that it satisfies the criteria of being meaningful, reliable, and distortion-resistant and reflects the quality of service. It is meaningful because it translates directly into growth in revenues. It is reliable because there is no measurement error or uncertainty. It resists distortion because inflows and outflows are both taken into account. It is responsive, meaning that when the relationship manager does a proper job of taking care of clients and their assets, net new money is likely to increase either directly through an increased share of the individual client’s assets or indirectly through referrals. By contrast, poor service and bad advice will result in outflows or negative net new money.

Assets under management as a metric is a direct driver of revenue. It is less suited, however, for use as a key performance indicator. While assets under management are meaningful in the sense that revenues are linked to this measure, they are far from a reliable measure of relationship manager performance. Profitability or return on assets (RoA) is more strongly linked to the asset mix and the performance of financial markets. Depending on the asset mix, the profitability of assets under management may be more reflective of the market than the performance of an individual relationship manager. Equity funds, for example, offer significant higher margins than money market funds.

Even though margins are relatively unresponsive measures and are usually fairly static, it is important to track them in relation to net new money. One reason is that this can prevent relationship managers from seeking to gain net new money at all costs. The relationship manager can grant special conditions to attract new money. Discounts and special terms are sometimes used to tempt new clients to enter the relationship. The bank needs to be careful that this is not done at the expense of profitability.

BALANCED SCORE CARD: SOFT MEASURES IN PRIVATE BANKING

The “soft” measures applied in the balanced scorecard system outlined in this chapter depend very much on the function of the employee or division. For a relationship manager, the measures most heavily weighted would be those pertaining to financial and client “dimensions.” As long as these measures are on target, there is little need for intervention. If there are problems meeting targets, however, the team leader may look for other ways to spot potential problems or to identify possible solutions. Such information might serve as an early warning signal. For each specific area, four items can be examined in detail:

For a detailed overview of the key measures that might be applied to private banking, please refer to the Appendix at the end of the chapter.

CONCLUSION

A private bank needs to be run according to targets. If there are no targets, it is impossible to measure achievements, deviations from targets, or performance as a whole. Quantitative targets as well as qualitative targets are necessary. The job of a CEO is to ensure that the company is going in the right direction. This is accomplished by continual monitoring and by keeping in close contact with staff. Once the direction is set and clearly communicated, employees need to be empowered to reach the goals and targets set. Resources are critical to delivery. Employees also require encouragement, controls need to be established and monitored, performance must be measured, and there must be compensation and rewards tied to these measures.

Assessing the right measures requires a clear focus on strategy, which needs to be simple and concise and expressed consistently to provide a meaningful basis. Companies must be honest and realistic in setting targets, avoiding traps such as failing to realise the difference between a mission statement and a strategy. The former is more general whereas the latter can be measured and evaluated in terms of achieving precise goals. It is important to base targets on realistic assessments (e.g., market share) that are truly attainable. This avoids internal wrangling when it comes to making forecasts used to set goals.

Performance management has been around for decades. It is only recently with the introduction of modern technology that it has become a highly technical discipline, allowing companies to gather information about past performance and to use this information to help predict success or failure. It has evolved into an effective tool that can spotlight problems at an early stage. Rather than serving as a dull counterpoint to the “real” business of a company, performance management has become an integral part of all phases of a business. This is true in service companies including banks, which in the past typically had a hard time measuring the true costs involved in their business.

In banking there are no items being produced on an assembly line. All areas of the company are aligned toward one goal: serving the customer. Each client will determine the yield on investment. For banks, the way forward must be to achieve the maximum sustainable profitability in this regard. Sustainability is understood, therefore, as engaging in those activities that offer the most benefit and value to each individual client.

NOTES

1. Charan, R. and Colvin, G. 1999. “Why CEOs Fail.” Fortune. 21 June.

2. Kaplan, R.S. and Norton D.P. 1992. “The Balanced Scorecard.” Harvard Business Review, Jan/Feb.

3. Drucker, P.F. 1995. “The Information Executives Truly Need.” Harvard Business Review, Jan/Feb.

4. Kim, W.C. and Mauborgne, R. 2005. Blue Ocean Strategy, Harvard Business School Press.

*In private banking, such an approach can be used to identify current problems and future potential. A bank is interested in the productivity or profitability of individual relationship managers, as well as in teams and divisions in relation to the full costs that they incur.

*Market purity refers to the strictness of segmentation. Low market purity exists when, for example, the Latin American team is also handling many clients from Germany or when the retail division in an universal bank does not refer its HNWIs to the private banking unit.

*The ‘net promoter’ score is calculated by subtracting the number of satisfied clients from the dissatisfied ones.

**In private banking, a relationship manager will present a “business case”—literally, this takes into account items such as the client’s assets that the manager believes that he or she can deliver within a given time period, and so forth.

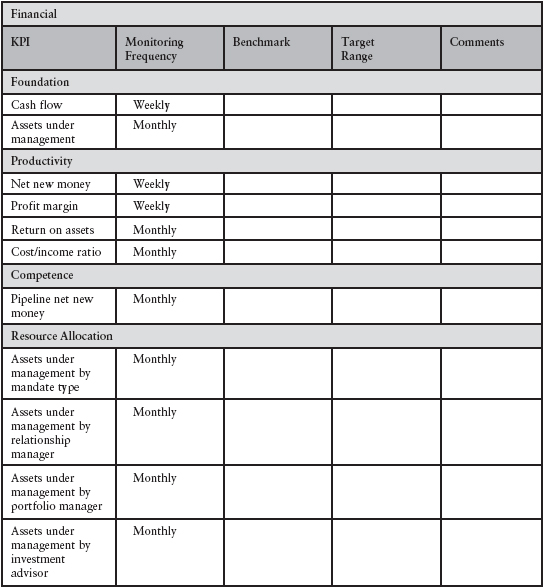

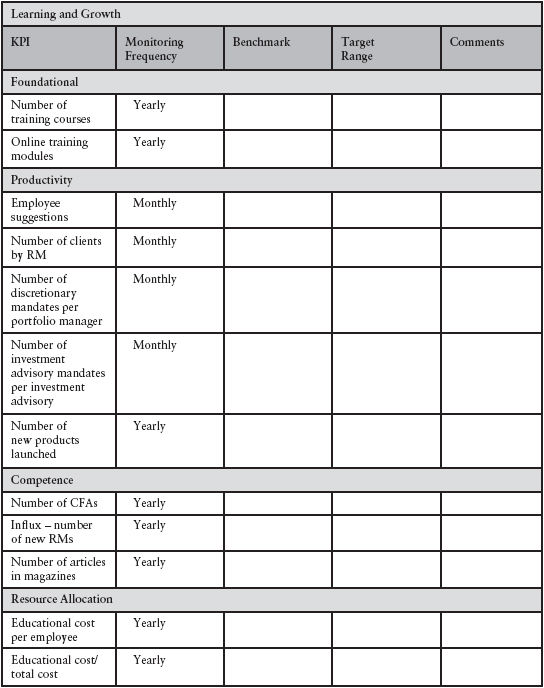

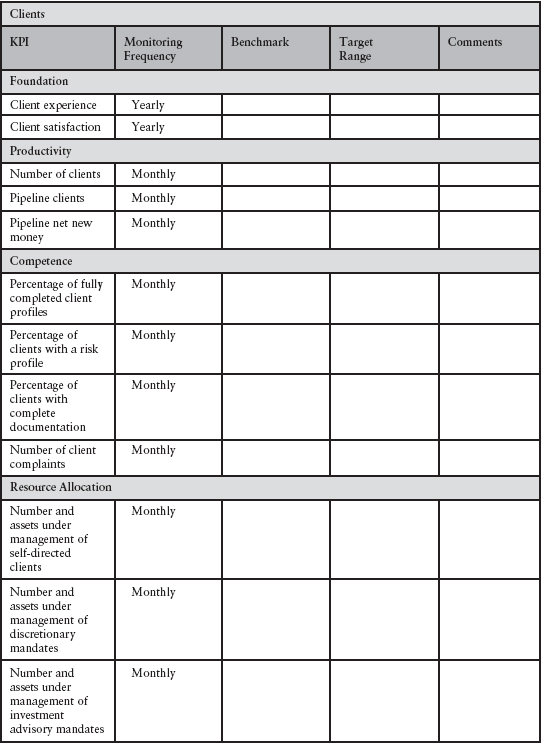

APPENDIX: KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

Key performance indicators in private banking are in one sense no different from those used in any other industry. The central measures are the level of client assets under management and especially flows of new client money (net new money). But a holistic approach is needed. For each of the main categories—financial/risk, learning/growth, clients, internal processes—these aspects must be included in measuring how successful the bank is in meeting targets. A balanced scorecard, as outlined by Kaplan and Norton, can thus be applied to private banking using Drucker’s diagnostic tools.

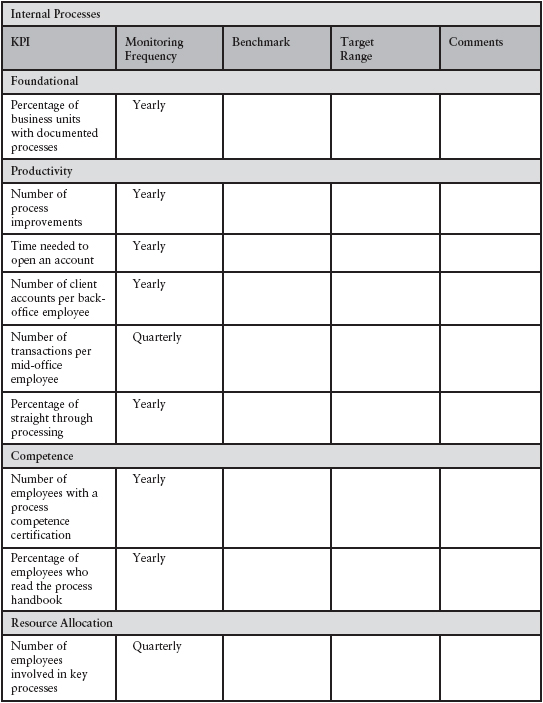

Tables 12.1–12.4 offer a breakdown of the main variables to be tracked when it comes to performance, both for the business as a whole and for individual relationship managers. It is important to identify both the variables that are tracked and their frequency to assign a benchmark and add quantitative comments where needed:

TABLE 12.1 Variables to Be Used to Track Education and Growth

Source: Author

TABLE 12.2 Variables to Be Used to Track Internal Processes

Source: Author

TABLE 12.3 Variables to Be Used to Track Clients

Source: Author

TABLE 12.4 Variables to Be Used to Track Financial Performance

Source: Author