Project Control in Practice and Prevention of Challenges to Effective Project Control

Overview of Project Control Process in Practice

The preceding chapter discussed the theoretical concept of project control. Sometimes, theoretical concepts do not align with reality. This chapter explains how project control is implemented in practice and some of the challenges it is exposed to, as well as how to surmount these challenges.

In practice, project control is often a multifaceted task undertaken by managers and practitioners working on projects. As discussed in the previous chapter, project control is a complex and iterative process. It is about the final step in management and during the control stage—the level of performance is compared with the planned objectives to find any deviation and corrective action taken as appropriate.

Research underpinning the project control inhibitors management (PCIM) methodology has identified several challenges and shortcomings of the project cost and time control processes in practice. These are discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter.

Prevalent Project Time Control in Practice and Shortcomings

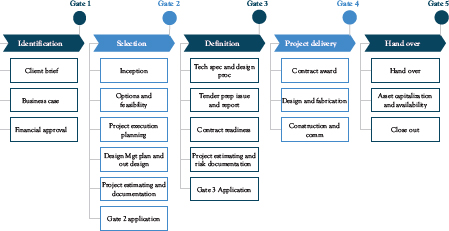

Although the research that informed the PCIM methodology was focused on the control of construction and infrastructure projects, the author has supplemented this chapter with his experience of working on other types of projects such as IT projects, research and development projects, transformation projects, consultancy projects, implementation of new financial services policy projects, and so on. The time objectives of projects are controlled by practitioners broadly following a common process. The prevalent time control practice as revealed by the PCIM project control methodology research is depicted in Figure 3.1 and described as follows.

Assessment of Duration of Tasks and Activities

The first step in the project time control process in practice normally involves an assessment of the resources available in the company to establish that there are adequate levels of personnel required to deliver the project. The duration of the project is decided at this stage. The methods for determining the duration of the project revolve around “assessment from experience” and “the use of calculations.” One problem with determining the duration of projects at this stage lies in the lack of involvement of supply chain partners. Therefore, durations of partners’ tasks are based on assumptions, which can sometimes be inaccurate.

Figure 3.1 Descriptive model of the prevailing time control process in practice

Visual Representation of Project Duration

The second step usually involves the development of a visual representation of the project duration, most often using scheduling software packages to produce a graphical output (Gantt or bar charts). Different forms of schedules are developed for different purposes. The different forms of schedules utilized in practice include:

• Tender schedule – which is the proposed schedule for delivering the project when it was tendered;

• Contract schedule – which is the schedule that is part of the signed contract documents and the one the project contractor must deliver to;

• Target schedule – which is a replanned schedule used by management to drive work during project delivery aimed at delivering the project quicker than the current master schedule. Therefore, the contract schedule is not always handed to the construction site team, instead the more ambitious target schedule is utilized;

• Stage schedule – which is a schedule developed for the different stages of the project; and

• Project master schedule – This is the current approved overarching schedule for the project, which has taken account of current change requests and incorporates all the work packages, and has therefore become the latest contract schedule. Schedules can also be referred to by “levels” as below:

• Level 1 schedule is the project’s master schedule which presents the key milestones and major activities of the project usually on one page;

• Level 2 schedule is the project management summary schedule which shows the project broken down into its major component including interfaces and used to show the integration of the work required to deliver the project;

• level 3 schedule is the control level schedule which is an integrated schedule of the project and contains all major milestones, procurement, design, execution/delivery, testing etc.;

• Level 4 schedule is the detailed network schedule and the schedule used for the execution of the project;

• Level 5 schedule is a more detailed breakdown of the level 4 schedule and used as a very tactical schedule to manage day-to-day activities of the project usually by supervisors on a short-term basis.

The assessment of duration and visual representation of the preceding project duration steps can be categorized as the planning phase of the project control cycle, the first step of the theoretical project control process.

Monitoring and Reporting of Progress

The third step of project time control in practice is normally monitoring and reporting. However, the PCIM research found that there is usually no dedicated monitoring process in place. Therefore, monitoring is usually ad hoc at best. Consequently, in practice, there is usually no due diligence on monitoring to ensure objectivity, leading to risk of nonfactual information being reported by project-level staff. Furthermore, the research shows that there is no real mechanism in place for reporting progress from the project site to the project/head office. At best, any reporting mechanism in place is often loose and unstructured.

This step of the project time control appears to move straight from monitoring to the analyzing stage bypassing the reporting process. It was found that in practice the reporting phase of project time control is only loosely incorporated into the overall project time control process. Most of the time, it was unclear if time is monitored directly by the project office or progress is reported to the project office by the project-level team. The most common time reporting structure in practice during construction projects is through progress meetings, which usually take place on a weekly basis. In the author’s experience (having delivered many projects as well as carried out consultancy performance reviews on dozens of projects), this informal reporting process, such as meetings between the client and the contractor and meetings between the contractor and subcontractors, is practised in most projects. This form of reporting structure is obviously not the most effective because necessary control action may be delayed between the interval of meetings. Meetings should not be discounted as they are a valuable method of discussing issues relating to the project and are often wider than project time control, but they should not be the main time control reporting avenue. Instead, meetings should just serve as a supplementary reporting structure or a high-level reporting forum.

Analysis

The fourth step in the prevailing project time control process in practice is the analysis of the information acquired through monitoring and reporting (albeit loose and unstructured). In practice, the use of robust project control analysis techniques like earned value analysis is not widespread, the prevailing practice when analyzing during time control is a qualitative evaluation of the current progress against the planned progress by marking progress on the project schedules (usually Gantt chart) to check if the project is ahead or behind schedule. This indicated that the Gantt chart doubled up as the time control tool in addition to being used as a scheduling tool. Hence what happens during the “analysis step” of the prevailing project time control process in practice is hardly analysis but interpretation. Interpretation is a very simplistic way of analysis during time control because this technique will hardly reveal the underlying reason for lack of progress or any problem lurking in the project that the project team should be wary of.

Action

The fifth and final step of the project time control process in practice, as customary with most control processes, is “action.” It was found that in practice, this appears to be another underutilized aspect of the project time control process. This is because the information generated from the previous step (analysis) is only interpretation and quantitative analytical tools are rarely utilized to reveal future trends. Hence, in practice, corrective actions to bring a project that is behind schedule back on track are quite often only reactive and usually end up not being effective.

Prevalent Project Cost Control in Practice and Shortcomings

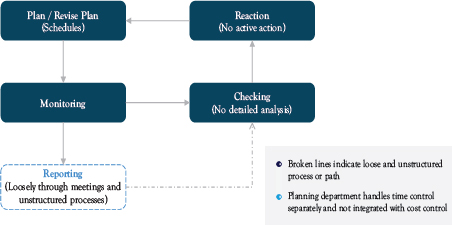

The cost control processes for construction projects utilized by practitioners who were involved in the research underpinning the PCIM project control methodology were also found to be common and similar to the author’s experience of working on other types of projects such as IT projects, research and development projects, transformation projects, consultancy projects, implementation of new financial services policy projects, and so on. The prevailing cost control process is shown in Figure 3.2 and discussed in the following section.

Cost Estimation

When there is a requirement for a new construction project, the first step is the estimating department is asked to price the job and prepare the estimate. However, quite often, no quantitative estimating method is used. The total project cost estimate is usually developed by obtaining quotations from subcontractors and suppliers for the various work packages of the project. After the tenders have been priced, a common practice is to ensure that every item, service, or package in the tender has a cost allocated to it in the hope that this will help control the cost of the package during implementation. For projects other than those of construction, for example IT projects, the cost estimating process is similar if the project is to be outsourced. However, for projects that are delivered internally by the company, the cost estimation for the projects takes into account the time to be expended by the various professionals (IT architects, business analysts, solution designers, project managers, and others involved in the project) who will be working on the project and the cost equivalent of these staff or how much will be paid to them if they are brought in as contractors into the business is calculated.

Figure 3.2 Descriptive model of the prevailing cost control process in practice

During project cost control, the second step involves monitoring and, as was the case during control of time, no clear distinction between monitoring and reporting appears to exist in the prevalent project cost control process in practice, although the reversal was noticed (reporting was more structured but monitoring was slack, which was the opposite for time control). During cost control, the monitoring regime in place is not usually robust enough because quite often, monitoring does not follow a periodic regime or utilize a dedicated structure such as computer tools or templates. For other projects such as internal IT projects, the monitoring of cost is even looser and reactive with the cost expended on projects usually extracted from the payment systems by the finance department and may sometimes not be able to be disaggregated easily from the many projects taking place within an organization. For consultancy projects, monitoring of cost is stronger since the services of people are what is usually being sold, time expended on projects is usually recorded on a system with the time expended for each resource, and the associated rate usually used to obtain the current project cost. The cost is usually compared against the agreed fee for the project if it is a fixed-fee consultancy project. If it is a time-based fee, the client is usually advised of the current project cost on a periodic basis such as weekly for comparison against the budget fee.

From the loose monitoring of project cost, the next step revealed involves reporting. As previously mentioned, the reporting mechanism during cost control in practice seems more robust than the monitoring regime. Research informing the PCIM project control methodology found that quite often the monitoring step is bypassed, moving straight from planning (determination of the project cost estimate) to cost reporting. This is because many practitioners alluded to the fact that they have site-based/project-level quantity surveyors (construction project cost professionals) tasked mainly with reporting cost to the project office. The project team rarely completes cost documents since anything to do with cost is considered strictly a quantity-surveying matter. Cost reporting was found to be more robust than cost monitoring on other types of projects as well; for example, in internal IT projects, the costs of resources expended are obtained from the financial system and reported to management periodically such as monthly. However, the project team on ground rarely has a cost-reporting responsibility. The cost-reporting responsibilities are usually the preserve of more senior project staff such as the project manager, and the project director discusses the cost of the project as compiled by the finance department at senior-level meetings such as program and project board meetings with the functional management of the organization.

Analysis of Cost Performance

The fourth step after reporting is analysis, but, unlike the prevailing time control process where interpretation is the norm rather than analysis, there is a wide usage of quantitative analytical tools and techniques for cost control. Practitioners control cost by considering cost and value, using tools like cost–value comparison and earned value analysis (albeit less frequently) to reveal overspend and its causes. Similarly, for other types of projects, cost is usually analyzed. For example, in internal IT projects, the finance department will usually obtain the cost of the projects from the finance system and analyze the cost of the projects. For process engineering projects, analysis of cost is also carried out in detail; here, cost of projects will typically be obtained from the finance system on a periodic (usually monthly) basis. This cost is then supplemented with cost information supplied by the cost professional responsible for the projects, usually called the cost engineer or cost controller. The costs of the projects are then analyzed by this cost professional utilizing techniques such as S-curves, cost of work done and value of work done analysis, anticipated final cost forecast, earned value analysis such as schedule performance index and cost performance index, and so on (cost analysis techniques are discussed in Chapter 8).

Action

The fifth and final step revealed for project cost control is “action” to control potential cost overrun. Although the analysis step is more detailed than was noticed in time control, there was no systematic way of acting when analysis showed the need for action. The PCIM project control methodology research showed that when analysis shows any cost overrun on an activity or work package in construction projects, the prevalent action involved having a meeting with the relevant subcontractor for the area with cost overrun to discuss the issue and how to mitigate the cost overrun or trying to manage the impact on the overall project by shuffling cost by finding other work package(s) with an underspend and reallocating the overrun cost to them. For other types of projects like internal IT projects, action will usually involve assessing the staff utilized on a project and reducing headcount or time spent. From the author’s experience and research, the action step of project cost control is usually reactive, panicked, and unsystematic with many actions taken not preceded necessarily by an action impact assessment on the project. It is not expected that every little project action should be subjected to impact assessment, but all proposed key actions at least should undergo an impact assessment.

Challenges to Minimize for Effective Project Control in Practice

One of the principles of the PCIM project control methodology is that project control is not devolved from the environment in which it operates. Therefore, there is a need to highlight the challenges of effective control of projects in practice and the provision of deeper insights into the day-to-day practical issues that make effective project cost and time control challenging from a practitioners’ perspective. The research that underpinned the PCIM project control methodology unearthed many challenges to the achievement of effective project control in practice. These challenges have been grouped under four themes based on their origin during the project control process. The categories and issues are presented in Table 3.1 and the challenges and prevention are discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter.

Table 3.1 Challenges to minimize for effective project control in practice

Challenge categories | Identified project cost and time control issues |

Organization | 1. Lack of integration of cost and time during project control 2. Lack of senior management buy-in 3. Complicated project control systems and processes 4. Lack of a project control training regime |

Project delivery approach | 5. Lapses in integration of interfaces 6. Project control not being implemented from the early stages of a project 7. Inefficient utilization and control of human resources 8. Limited time devoted to planning how a project will be controlled at the outset |

client or owner issues | 9. Excessive authorization gates 10. Use of adversarial and noncollaborative forms of contracts 11. Communication problems within client setup 12. Obstructive client representatives |

Project team issues | 13. Lack of detailed/complete design 14. Lack of trust among the project partners 15. Limited time devoted to project control on-site 16. Nonfactual reporting |

Challenges Stemming From the Organization

Challenges stemming from the organization are the most important barrier to effective project controls. In fact, research by Munizaga and Olawale (2022) has found that many factors that engender project failure can be linked to organizational issues. This is because organizations may sometimes exhibit certain behaviors or lack certain practices that make effective project control more challenging. The project control challenges emanating from this category are discussed below.

Lack of Integration of Cost and Time During Project Control

This is a major obstacle to effective control of the cost and time objectives of projects. Project control in the “real sense” can only work if cost and time are integrated. However, this is not always the case in practice. Quite often in many organizations, there has been a little office with the planners (schedulers) in, there has been a little office with the cost or commercial people in, and never the two shall meet. This kind of situation should be avoided to achieve effective project cost and time control because lack of integration of time control with the cost dimension of the project would not yield the necessary information needed to act on a project effectively. To buttress the importance of integration of cost and time during project control, the classical research by Chan, Ho, and Tam (2001) also found that there is a strong relationship between cost and time of the projects. Additionally, this integration principle of cost and time has been exploited by Ballesteros-Pérez, Elamrousy, and González-Cruzc (2019) in developing time–cost trade-off models that help with fast-tracking the progress of projects.

Lack of Senior Management Buy-In

Senior management of some organizations often do not appreciate the benefits of a project control system and consequently do not give support to instituting a dedicated project control culture in the organization. Lack of senior management buy-in and absence of the right project control culture in an organization will often lead to project control being implemented half-heartedly with limited investment and training. Therefore, it is essential that management create a project control culture among all employees and provide all the support and encouragement needed. Research also supports this assertion; for example, it has been shown by Young and Poon (2013) that top management support is significantly more important for project success than any other factor. More specifically, Kanwal, Zafarb, and Bashira (2017) found from their research that top management support is important for project success, especially outcome control (or scope control) and cost and time control, that is, the classic “iron triangle” as discussed in Chapter 2.

Complicated Project Control Systems and Processes

Quite often, organizations put in place project control systems and processes that are complicated and end up being a bottleneck. They are sometimes considered burdensome and used half-heartedly. Consequently, the necessary information and data essential to achieve effective project control are often not up-to-date, inaccurate, or unavailable, leading to futility of project control efforts. Although implementation of projects is a relatively straightforward process, some systems overcomplicate its working, and the project management staff who use the systems do not like highly complicated systems. This is supported by the research by Bryde, Unterhitzenberger, and Jober (2018) who show that a small number of simple metrics and indices are more effective at communicating performance of projects than a large number and complicated ones.

Lack of Project Control Training Regime

This challenge relates strictly to the quality of training and knowledge that the people working on the project have about project control. Project control would be more effective if project delivery staff understood the science of project control better than they currently do. Research that underpins the PCIM project control methodology revealed that there is still a misconception that project control is just about Gantt charts as there is inadequate understanding of more robust project control techniques such as earned value analysis, progress analysis, S-curves, and so on. An organization that is serious about delivering projects effectively should not only put in place the necessary project control systems and processes but will also need to provide the necessary training needed to implement them correctly. Research by Bryde et al. (2018) has found that adequate training of all members of the project team, including contractors, is crucial for the smooth operation and use of project control systems.

Challenges Stemming From Project Delivery Approach

The importance of project delivery competence is buttressed by the PMI (2020), which found that 69 percent of organizations highly value project management but only 22 percent use standardized project management practices throughout their organization. Where the project management capability within an organization is not mature sufficiently to support the type of projects being delivered by or in the company, then project practitioners will find it challenging to deploy project controls successfully.

Lapses in Integration of Interfaces

One of the challenges of effective project controls is that practitioners often find it challenging to integrate the different interfaces of basic projects, let alone complex projects. The effect of this is that project control becomes a more difficult task. The numerous interfaces that often characterize many projects are not insurmountable, although the challenges they present cannot be underestimated. To mitigate this in practice, adequate planning is important as this is often lacking in the haste to start projects early. Adequate planning will reveal complex interfaces, therefore necessitating better preparation on how these interfaces will be controlled, as corroborated by Arrto, Ahola, and Vartiainen (2016) who found that integration is beneficial and creates value during the project delivery and has long-term value-enhancing impacts.

Project Control Not Being Implemented From the Early Stages of a Project

The project delivery team often does not pay much attention to the project progress and performance at the early stage, believing that there is still enough time to recover the project if progress stalls. However, as the project progresses, then the slippage can move from not being critical to becoming more critical or even moving to the critical path of the project (see Chapter 7 for information on CPM). Lack of attention from the very start of a project will subsequently lead to a frantic rush to finish the project through acceleration, which consequently impacts project control negatively and quite often increases the project cost. Therefore, it is important to always implement monitoring, reporting, and taking appropriate corrective actions right from the outset of a project, enabling potential project problems to be revealed earlier and controlled in an orderly and systematic manner.

Inefficient Utilization and Control of Human Resources

The efficient use of human resources is an important consideration in the successful delivery of projects. Therefore, eradicating unproductive use of labor is always of major importance in achieving effective cost and time control of projects. However, for example, in construction projects, the project delivery team on-site often finds it challenging to control the use of labor resources efficiently, which negatively affects the project control process. The research that informs the PCIM project control methodology revealed that labor utilization on projects is often not managed efficiently and sometimes not utilized as planned since most projects usually involve significant manhours, for example, digging and building in engineering, infrastructure, or pipeline projects, or coding and testing as in software development and IT projects. Not being proficient in the management of human resources will quite often have a detrimental impact on the effective control of the cost, time, and quality of the deliverables of a project.

Limited Time Devoted to Planning How a Project Will Be Controlled at the Outset

The project control approach to be adopted for a project needs to be planned at the outset of a project so that the project management team is aligned. Due to the varied level of experience of the project team members, alignment on project control approach is only achievable with the setting up of a set of project control guidelines at the outset. However, oftentimes how a project will be controlled before commencement of the project is not planned. This usually leads to an unstructured and non-systematic project control effort, which does not bode well for effective project control. The main reason for this is that, quite often, there is not enough lead time from when the contract to deliver a project is awarded to a contractor to when the contractor starts the project or for internally delivered projects, from when the approval to proceed is received from management to the project’s start date. This leaves a very limited period for the project team and management to plan how the project will be controlled; it also hinders the installation of the necessary processes and systems that will ensure effective project control. The period between approval to proceed for internally delivered projects or tender receipt from external contractors and starting of work is very often “telescoped” and not sufficient. Consequently, many activities are rushed, leading to problems developing on the project. Research by Irfan, Khan, Hassan, Hassan, Habib, Khan, and Khan (2021) has found that preproject planning is important for the success of projects.

Challenges Stemming From the Client

When projects are being delivered to a client, some barriers to project control may emanate from the client processes and their approach to the project. Usually, this will relate to external clients, but it also covers projects delivered to business units or functions by their organization’s project delivery team. To the project management team, the business unit is a client or customer.

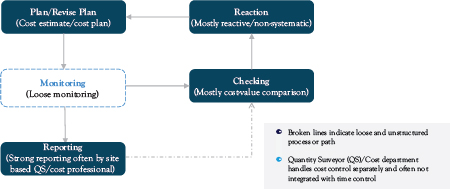

Excessive Authorization Gates

A stage gate process is an aspect of project governance that enables decision makers to assess that a project is being delivered as planned. The stage gate process will provide an organizationwide approval process where the project team needs to seek authorization from members of an authorization board to progress a project from one stage to another or stop the project if certain criteria are not met (see Figure 3.3 for an example of a stage gate process from the author’s experience). However, with everything, balance is important. If authorization gates are not proportionate to the value, pace, and complexity of projects being delivered, the project team’s ability to make agile, tactical decisions may be restricted and become detrimental to effective project controls. The reason for this detrimental effect on project control is that, quite often, time is spent waiting for approval from a manager who may not be part of the project team and decisions that are by no means strategic cannot be made by the project team. The authorization gate can then become a bottleneck as it unnecessarily causes delay. While having authorization gates is a good management practice, too much authorization gates could lead to bureaucracy and inflexibility, which does not bode well for effective time and cost control.

Figure 3.3 Example of a stage gate

Use of Adversarial and Noncollaborative Forms of Contracts

Projects usually involve interaction or use of other parties to execute the project. These relationships are usually guided by contracts. In process engineering projects, civil engineering projects, and building construction projects, for example, traditional standard forms of contracts like IChemE, ICE contract, and JCT contract are used, respectively. The form of contract adopted on projects helps in the allocation of risk and responsibilities to match the characteristics of different projects. However, contracts that are used on projects can either be collaborative or adversarial (where self-interest of the contracting parties mostly takes priority over everything, including their responsibilities on the project).

The use of adversarial types of contracts can often be a bottleneck during the project control process, as they do not aid openness and collaborative working and may sometimes prevent project partners from owning up to the mistakes that have been made. A classical empirical research by Larson (1995) asserts that “strictly adversarial” and even “guarded adversarial” contract approaches exhibited inferior project cost, time, and technical (scope) performance than those projects that employed a partnering approach. The challenge is most standard forms of contract used for a project have been traditionally adversarial; however, the project parties can overcome this challenge by having an ethos of openness and collaboration as part of their general project approach. There are now standard forms of contracts such as the standard forms of project partnering contracts and the NEC suite of contracts that have partnership and collaboration at their core.

Communication Problems Within Client Setup

Ineffective communication mostly within the client’s organization often brings about conflicting information. Lack of clear and correct communication between a client’s office staff and the project site representatives can sometimes lead to confusion. Inadequate or poor communication has also been identified by PMI (2018) as the primary cause of 29 percent of project failures. The research that informed the PCIM project control methodology also found that some client representatives communicate the changes they want without the client necessarily instructing it. This sometimes cause arguments, delay, and increased cost that the client later disputes. Research by Bryde et al. (2018) has found that high information asymmetry typically exists between project clients and contractors delivering the project, which needs to be addressed for project success. The importance of effective communication for effective project control cannot be overstated because project control relies on information and data. For effective project control to be achieved in practice, it is important that lines of communication are clear, and the most up-to-date information is communicated on time and to the relevant persons during the project control process.

Obstructive Client Representatives

Some client representatives can be obstructive in a bid to justify their importance and this does not create a team effort and a sleek project control process. According to the research underpinning the PCIM project control methodology, management problems with the client affecting project control quite often result from client representatives wanting to make sure that their position is safe by being overzealous to make sure that they’ve got a job. This kind of attitude from client representatives does not spell success for project control efforts and the project. To avoid this, it is imperative that all the project parties adopt a nonadversarial and collaborative approach for effective project control. In the author’s experience of delivering projects and consulting on projects, the interaction between the client representative and the project management team is important in facilitating good project progress and budget performance through the selection of a client representative who can gain the confidence of the project team quickly. Additionally, client representatives on projects should understand that they have a fiduciary responsibility to the client. Fiduciary responsibility means acting on behalf of another person but in so doing putting the interest of the person you are acting far ahead of yours while in that capacity, with an ultimate responsibility to do so in good faith and trust.

Challenges Stemming From the Project Team

Since project delivery is a team effort with project control implementation relying on individual team members, some of the challenges to effective project control also stem from the project team.

Lack of Detailed or Complete Design

Most projects often must go through a design stage, be it designing a process plant, an infrastructure facility, or an IT system. However, the research that underpins this chapter revealed that for infrastructure and construction projects, for example, there has been a general decline in the production of detailed design, especially with the increased usage of the design and build procurement route. This sentiment would likely be reflected in other types of projects as well, especially with the increased pressure to get to market quickly, which has led to the development of, for example, new methods of delivery in IT, for example, Agile methodology. The real issue for the project delivery team is that the designs that are coming through for delivery and execution may not have the level of detail in them required for appropriate pricing or to do the job one-time, accurately and without the back-and-forth clarification with designers, which consequently causes delay, design/scope changes, and additional cost. Although it is not always possible to produce a detailed design for all projects, designing the project to as much detail as possible at the outset is bound to reduce resource and cost uncertainties associated with incomplete designs, thereby giving the project time, scope, and cost control effort a better chance of being effective. See Table 3.2 for case study of the negative implication of incomplete design on the cost and time objectives of a project.

Table 3.2 Real-life case study of the negative implication of incomplete design on the cost and time objective of a project

• The author was part of a consulting team that was engaged by the directors of a company, “Musicven group” for anonymity, that was developing an entertainment venue.

• The aim of the consultancy work was to carry out an independent review of the entertainment venue construction project to ascertain the reasons for the increase in the cost of the project.

• The overall cost of the entertainment arena had increased since the project was started. the cost increased by more than £6 million.

• The review carried out identified that the use of incomplete design was one of the primary causes of the cost overrun the project was facing, accounting for more than 40 % of the cost overrun.

• The review carried showed that Musicven group was under pressure for the entertainment venue to be ready by a set date. However, the assessment by Musicven group and their advisers concluded that there was not enough time to complete the full design of the entertainment venue, tender the project, appoint a contractor, and construct the entertainment arena before the set date.

• Therefore, the contractor tendering process and construction work had to begin before the building design was completed, resulting in the preliminary cost estimate and the tender to be based on an immature design.

• The consequence of this was that during the contractor tendering, the cost estimates for major aspects of the project were not accurate. as a result, when the design for the various aspects of the projects was completed during the project and then priced, their eventual cost showed a large increase than what was initially estimated.

• Additionally, because construction of the entertainment venue also started before the completion of design for some key areas, cost increases occurred due to the contractors waiting for the design and rework on some parts of the project that had been completed to accommodate the consequential effect of the completed design. an example was the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning services for the entertainment arena, which following the completion of design, had a price increase of more than 35%.

• Finally, in addition to the significant cost overrun encountered by the project, the project eventually encountered time overrun of more than 15 weeks, as a result of, waiting for the complete design of areas of the work that had not been designed and rework due to the impact of newly completed design.

Lack of Trust Among the Project Partners

In projects, there is usually a collection of participants all working together toward completion. So, some form of cooperation and trust is usually required from all parties to the project to complete the project even though they all try to protect their various interests. However, lack of trust often exists among the project team members. For example, it emerged from the PCIM methodology research that sometimes a project partner may try to hide a mistake from the rest of the project team in the hope that it can be rectified without the rest of the team knowing about it. This lack of transparency often leads to time and cost penalties of such errors not being analyzed on time. Any lack of transparency is bound to be problematic in the quest to achieve effective cost and time control, since information about the project cost and time performance is essential for the project control process. The importance of teamwork has been identified by the research of Oh, Lee, and Zo (2021) as important to project success. Trust has also been found by the research of Rezvani, Changa, Wiewioraa, Ashkanasy, Jordan, and Zolina (2016) as serving to enhance project success including in complex project situations.

Limited Time Devoted to Project Control On-Site

Projects are usually developed and delivered under time constraints and quite often the project delivery team members are not able to devote enough time to project control, as they are usually busy expending time and effort on core delivery activities. One reason for this is the impression that it will be very onerous to participate fully in the project control process and attention should be focused on completing the project, which can at times be frantic. Reports are therefore half-heartedly produced and rushed, usually not up-to-date and mostly inaccurate. The PCIM project control methodology research found that many members of the project delivery team are frequently of the opinion that they should be managing progress, delivering, or executing the project and they are usually under time pressure. Leading the project delivery team quite often means trying to focus on the issue at hand, and those leads might have been working overtime, leaving little time to report anything else. Consequentially, the data that is obtained from the project delivery team quite often isn’t very good. The above sentiment that project control is an add-on to the duties involved in delivering a project can only be addressed by instilling a project control culture in an organization to the extent that the project management team, both on site and in the office, realize that project control is a good project management practice to be embraced by all.

Nonfactual Reporting

Reporting is a key step in project control, as it is how the status of the project in relation to the plan is communicated to the appropriate stakeholders including those with the responsibility to act should the project not be progressing as planned. The research that underpinned the PCIM project control methodology revealed that poor reporting is a common problem during project delivery and this problem needs to be dealt with for project control efforts to be effective. It was clear that reporting of information by the project delivery and sometimes management team is not always factual. One of the reasons for this is that project delivery personnel or even management are sometimes unwittingly optimistic about the status of the project or at worst dishonest to mask issues in the hope that they can bring a failing project back on track without raising the alarm to their senior staff based in the office. This problem has also been highlighted by the classical project reporting bias research by Snow, Keil, and Wallace (2007), which found that project managers produce biased reports 60 percent of the time and the bias is more than twice as likely to be optimistic than pessimistic. Consequently, the reported information, which is used during the analysis stage of project control, ultimately produces results that will not give a true reflection of the project. Therefore, areas needing corrective action will not be obvious to senior managers, making time and cost control ineffective. To give project control a better chance of success, it is important that reports are factual, true, and accurate. This will enable the information in the reports to highlight the true project progress, scope, and time status so that actions can be taken to bring the project back on track if necessary. See Table 3.3 for case study of nonfactual reporting.

Table 3.3 Real-life case study of nonfactual reporting: Crossrail mega project

Introduction

The author was part of the consulting team that was appointed by the project sponsors, Transport for London (TfL) and the UK Department for Transport (DfT), in October 2018 to carry out independent financial, commercial, and governance reviews of the Crossrail mega project following the sudden announcement that the project had encountered delay and cost overrun. Commercial reporting and oversight were one of the many areas that the project sponsors wanted the team of consultants to review.

Background

London’s Crossrail was planned as a £15 billion mega project to provide a new cross-London rail service, running through a newly constructed section beneath central London, including new rail tunnels and underground stations. The project was meant to be completed and opened for operations in December 2018. However, in August 2018, the project developer, Crossrail Limited, announced that the project could not be completed and opened for operations on the planned date and will be delayed for more than nine months! (It was eventually delayed for three and half years). Additionally, it emerged that the £15 billion would not be enough to complete the project and the project requested an additional funding of £2 billion! The fact that the project will be delayed and that it will encounter cost overrun of such magnitude came as a surprise to the sponsors and stakeholders because up until that point all the reports issued by the project had maintained that it was on track to be opened by December 2018. Surely, a delay of more than nine months and additional funding requirements of that magnitude did not just appear to the project management team four months before their reported opening date.

Findings in relation to reporting

The author and his team found, among other things, that factual reporting had not been happening on the project for a long time. It was found that the project’s performance monitoring and reporting has not led to timely and adequate advance notice being provided on the need to materially change the opening date and the resulting significant cost impact. Although there was reporting flow from the project teams to management and the project leadership/board and to the sponsors, “the resultant reporting within and by the project was neither sufficiently timely nor sufficiently clear as to the impacts and magnitude of the range of probable consequences of the issues within the project” (KPMG’s independent review of Crossrail report 2019). In essence, the warning signs of the delay and cost overrun had been there at least 12 months prior to the announcement and that most project staff on the project knew that the December 2018 opening date was not realistic, especially as some key parts of the project did not start when they should have started. For example, the dynamic train testing should have started in early 2018, but it did not and that would have made it very clear that the project would be delayed. However, because the project had been successful in the early stages and had built a reputation of being a model project, the leadership team of the project wanted to hold on to this reputation and continued to report that the project was on-time and on-budget. Despite the signs showing otherwise in the hope that they could recover the situation, they did not report externally the challenges being faced long beyond when they should have done.

Project control is important in preventing project failure. However, achieving effective project control in practice is often challenging. The challenges to achieving effective cost and time control of construction projects in practice as well as recommendations to address these have been described. Sixteen key challenges were identified with many submissions put forward to address them. These are classified into four categories based on their origin as follows: (1) from the organization; (2) from the project delivery approach; (3) from the client; and (4) from the project team. It was recommended that cost and time control should also always be integrated, since controlling one without the other is unlikely to be effective. Factual and accurate reporting was also seen as important in avoiding some of these challenges.

Adequate planning was put forward to ensuring better preparation on how complex interfaces will be controlled on projects. Similarly, it was recommended that project control systems and processes should always be in place before rushing to commence a project. However, it was highlighted that authorization gates should be proportionate to the type of projects so that they don’t lead to unnecessary bottlenecks in the project control process. Finally, the importance of good communication for effective project cost and time control was stressed since it is essential that lines of communication are clear and the most up-to-date and accurate information is communicated on time and to the relevant persons during the project control process. Being aware of these challenges will help project control practitioners and organizations as they will be able to guard against them during the project control effort leading to the achievement of improved project controls.