Fundamental Concepts of Project Control

What Is Project Control?

Projects are usually executed on a budgeted capital and therefore are required to be completed within the available capital. Projects are also typically required for a purpose and therefore need to be completed before a deadline and to an agreed scope so that they can be utilized for the purpose intended. The need to complete a project within a capital budget, to a required scope, and delivery by a specified date point inherently to cost, scope, and time being arguably the most important objectives of most projects. Delivery of projects within a monetary budget, to an agreed scope, and by a specified date then become constraints imposed on projects. The financial constraint demands that the project costs be controlled (cost control) and the delivery by a specified date will require that the time expended on a project be controlled (time control). The successful control of cost and time requires scope control.

Cost control, scope control, and time control are important in projects so that cost overrun, scope creep, and time overrun are prevented. However, delivering projects within their cost estimates and on time has been considered to be challenging. There are many accounts of projects overrunning their cost and time. The seminal Egan (1998) report in the UK sums this up by stating that “projects are widely seen as unpredictable in terms of delivery on time, within budget.” The management tool for facilitating the predictability and completion of projects on time and within budget is “control.” Generally, controlling is an integral part of management with the function of management usually described as planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. Similarly, in the project context, control is also one of the major tools of project management; this is apparent from most definitions of project management where control always gets a mention. For example, the APM defined project management classically in its Body of Knowledge (BoK), 5th edition, as the process by which projects are defined, planned, monitored, controlled, and delivered such that the agreed benefits are derived. In fact, it can be argued that the role of the project manager during the execution phase mainly revolves around monitoring and controlling the project to enable successful delivery.

The Concept of Project Control

In a bid to discuss the issue of project control, it will be appropriate to start the discussion from the body of knowledge known as project management. Project management arose from the need to manage projects. Project management differs from the normal day-to-day management of businesses and organizations. A project is a unique, transient endeavor undertaken to bring about change and to achieve the planned objectives (APM 2019) with the intention of completing the project within a specified time, cost, and to a required quality standard.

What then is project management? Project management has existed informally for many centuries since the ancient projects we know of, such as the pyramids of Giza, Colosseum, Great Wall of China, would have relied on some of the principles of modern-day project management such as planning, monitoring, control, and so on to complete these projects successfully. However, modern project management is a relatively new field of management that evolved in recent decades in a bid to manage the set objectives of a project and associated activities effectively. Therefore, the Project Management Institute (2021) in the United States has defined project management as the “application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements.” The APM (2010) in the UK has similarly described project management as the process by which projects are defined, planned, monitored, controlled, and delivered such that the agreed benefits are realized. Effective project management requires planning, measuring, evaluating, forecasting, and controlling all aspects of a project including quality and quantity of work, costs, and time. It is evident that controlling is a major part of project management. The aim of controlling is to ensure that the future that is desired from a plan comes to fruition. Therefore, since projects are manifestations of the future of a past plan, the need for control in achieving that plan is crucial. The reality is that the objectives of a project would rarely be met on time and within budget unless the project is controlled in such a way that the deviations from plans are detected and corrected in a timely manner.

Factors That Are Controlled in a Project

Traditionally, the most important control areas in a project include the following:

• Control of time;

• Control of cost;

• Control of scope and quality (scope in this book will be taken as including quality because the scope of a project includes the specification of quality required);

• Control of procurement and supply;

• Control of logistics; and

• Control of resources.;

However, from the above, three factors, namely, time, cost, and scope, are regarded as the fundamental areas requiring control in a project. So important are these that classical project management literature has referred to cost, time, and quality as the “iron triangle,” first proposed by Dr. Martin Barnes in 1969 (Zwikael and Meridith 2021) or the triple constraints of projects as discussed in the next section.

The Triple Constraints

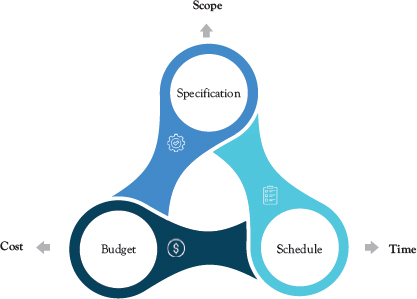

As mentioned previously, the most common areas needing control are cost, time, and quality/scope (the triple constraints). From the onset of project management, successful project execution and the ultimate objective in project management has been about achieving the performance specifications (scope and quality) on or before the time schedule and within the budgeted cost. This constitutes the triple constraints (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The triple constraints of project management

For the project to be successful, the three constraints would have to be controlled effectively. Therefore, the emphasis of project control is usually on the following:

• Time (progress): The aim of time control is to keep the progress of the project on schedule and minimize time overruns.

• Cost: Cost control monitors how much is spent on the project against budgets to highlight and explain variances, control cost increase, prevent unauthorized expenditures, and update the cost baselines with the forecast cost to completion.

• Scope: The aim of scope and change control is to facilitate the governance of change to the scope of the project including allowing only the necessary changes and approval. Scope control also includes quality control, which covers the management of the work contained in the scope to achieve the desired requirements and specifications avoiding/minimizing errors and mistakes.

There are three basic types of controls as described below:

• Cybernetic control, which is self-regulatory automatic control that operates in a closed system that uses a self-correcting feedback loop for the control. By this, we mean measurements are taken by the system and sent automatically for comparison against some predetermined performance requirements. If deviations from the performance requirements are found, the system then acts automatically to correct the deviation. The common thermostat is a good example of this.

• Go/no-go controls are not automatic. However, like the cybernetic control, they also involve the use of predetermined performance standards where another entity that is inside or outside the system tests the current performance of the system against some predetermined performance standards usually at regular, periodic intervals. Most of the controls in project management fall into this category. However, because the check is not automatic and happens periodically, it also allows errors to build up before they are identified at the next check.

• Postcontrol is also known as postperformance controls, reviews, or postproject controls or reviews. It is applied after the project, but it is not a vain attempt to alter what has already occurred. It is directed at improving the chances for future projects to meet their goals.

In a project-specific environment when the activities of a project are not progressing as planned, then action is taken normally. The actions are focused on a single exclusive objective of bringing the project back in line with its schedule or cost budget. There are two ways of implementing the control needed. These are as follows:

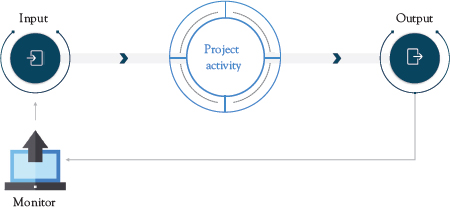

• Feedback control: This type of control monitors the output from the activities of a project and then adjusts the input to the activities as necessary to achieve a desired performance output (see Figure 2.2). The risk of this approach is that unless instantaneous feedback is obtained, the system may not produce information quickly enough to allow action. In order words, it is a reactive control. Ironically, feedback control is the most common form of control utilized for projects. That is, where project reports of all areas of the project are produced or obtained, performance is then analyzed against the set standard and then corrective actions are taken as appropriate.

Figure 2.2 Feedback control system

• Feed-forward control: This is applicable for activities and project operations where what is happening is well understood. Feed-forward control involves the monitoring of the input

to an activity before it starts or as the activity is ongoing and compared not with the output of that activity, but with the input required to achieve a desired output. The input is then adjusted accordingly impacting the desired output of the activity in question (see Figure 2.3). The feed-forward control is a proactive and active control process. That is, on projects, the feed-forward control consists of checking proactively the plan for an activity against the plan that will achieve the desired output. Where inadequacies are found, control actions are then taken by adjusting the planned input, for example, increasing the level of resources required for that activity. In essence, this control is performed on an activity before that activity is carried out or as it is progressing.

Figure 2.3 Feed-forward control system

Project Control Cycle and Steps

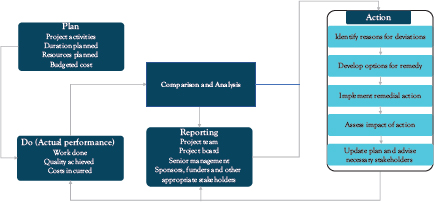

The project control cycle involves planning, implementing the plan, monitoring actual output, and recording it, reporting actual as well as planned parameters and their variations, and finally taking corrective action.

It is important to note that project control is not a one-time event; it is like driving a car to a planned destination. However, to reach the destination successfully, the driver needs to be in control all through the journey, following the key steps of driving a car and the rules of the road. On a project, the process of project control is a continuous feedback loop right from the conception of the project through to completion. However, this continuous feedback process is usually achieved in four phases: (1) setting planned performance standards, (2) comparing these planned standards with actual performance and forecast future results, (3) reporting the results as appropriate, and then (4) taking required corrective action as appropriate to recover or minimize the deviation from planned performance to return the project to the desired position or as close to it as possible. A typical project control cycle is shown in Figure 2.4.

In practice, the project control steps will usually involve the following:

1. The definition of the performance standards planned for a project traditionally will be the “iron triangle” explained earlier (budgeted cost, time, and scope/quality specifications), but more recently other performance standards are considered such as stakeholder satisfaction, resource requirements, sustainability, usability, and so on as explained in the section titled “When has a Project Performed Successfully?” in chapter one.

Figure 2.4 Typical project control cycle

2. Then, these performance standards are compared with the actual project performance to date. Schedule, cost budgets, and scope are compared to the progress of work, associated cost, and achieved scope. The remaining time to deliver the work and necessary cost of work remaining are then established and used to forecast the completion date of the project and outturn cost.

3. Reports are produced to present the outcome of this comparison, which are then shared with the appropriate internal and external project stakeholders.

4. Finally, whenever actual performance deviates significantly from the planned performance standards, corrective actions are taken as appropriate to bring the project back on track if possible or minimize the impact.

The main steps to the project control process as outlined above are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Planning

Planning and controlling are like “twins” in the project implementation process. This is because planning cannot achieve success without control while control itself could not be done without plans. Although planning and control are usually used together as a project management tool, they are quite distinct, with planning being a step within the project control process. Broadly, planning refers to the establishment of the goals and objectives of a future task or ongoing task (in the case of replanning), the setting out of the associated activities making up the task, the procedures, and the resources required to carry out these activities. Principally, planning is the setting out of what must be done and how to meet one or more objectives before proceeding to act in accordance with what has been set out. The plan captures in one concise document what needs to be done and the delivery approach. The plan documents all the material aspects relating to the delivery of a project including objectives, strategic approach, resources, cost, timeline, key milestones, and so on. Project planning is the modeling of a project, comprising the documentation of how the triple constraints (as discussed in the section titled “The Triple Constraints” earlier and shown in Figure 2.1) will be satisfied.

More specifically, project planning is basically planning in a project environment, with the APM (2015) describing project planning as the process of identifying the methods, resources, and activities necessary to accomplish the project objectives. Therefore, project planning involves the development of multiple plans: for the scope and performance dimension (the WBS), schedule dimension (preferably a network diagram), cost dimension (a financial estimate), and so on. The section below provides an overview of the project plan and its content.

Project Plan and Its Content

A project plan has often been confused with a project schedule, but it is worthwhile to note that while a project schedule and program are often called project plans by some practitioners, a project plan is not a project schedule. This is because a project schedule usually lays out project tasks and timings and enables the monitoring and controlling of progress as work proceeds, but the project plan contains the project schedule, and a lot more besides such as implementation strategy, configuration management, organization roles and responsibilities, and so on, as shown in Table 2.1. Project plans aid coordination and communication and help avoid problems during the execution of projects.

Table 2.1 Typical content of a project plan

Section | Typical contents |

Project summary | Project summary An overview of the project including background information on the project and the key particulars and information about the project. |

Project objectives and requirements | Describe what the project sets out to achieve as contained in the business case and the key specifications, features, and performance standards of the project that need to be met. |

Approach | A detailed explanation of how the project will be implemented including any methodology and procedures that will be followed. |

Timeline and milestones | An outline of the overall timescale for delivering the project with important milestones clearly stated. |

Scope | Information on the boundary of what the project is delivering including setting out of scope area for the project, especially those that stakeholders might logically consider part of the project but are not within scope of the project (for example, work being delivered by another project or which will be delivered as part of a future phase). |

Configuration management | The approach that will be used to manage the creation and control of the various aspects of the tasks, outputs, and scope of work required to deliver the project. |

Dependencies | Documentation of things, decisions, other projects, and others that the project relies on to start, progress, or complete. This will include internal and external dependencies. |

Resource needs | A summary of all the resources that are required to complete the project. |

Roles and responsibilities | An outline of the project roles and responsibilities, which could also include a RACI matrix. |

Assumptions and constraints | A list of the assumptions that have been used in planning the project as well as any limitations that the project needs to work within. |

Schedule | A diagrammatic depiction of the activities and tasks that will be delivered to achieve the project including their timing, sequencing, and interdependency relationships. |

Cost | A document of the cost estimate for executing the project, overall budget, and how cost will be managed during the project. |

Risk and issue management | Documentation of the key risks of the project, their analysis, and mitigation/management approach and a log of the current issues and how they will be managed. |

Quality management | A description of processes that will be used to monitor and control the outputs and works to deliver the project so that they meet the performance and quality specifications agreed for the outputs, works, and overall project. |

Deployment and implementation approach | Explanation of the entry into service strategy for the completed project including how the completed project will be implemented such as timeline and phasing if applicable. |

The project execution plan (PEP) is a document that establishes how the execution of a project will be managed to completion. The PEP describes how the overall execution phase of a project will be managed to meet the requirements of the project. In documenting how the various aspects of a project’s execution phase will be managed, the PEP usually incorporates the roles and responsibilities of the project’s parties in relation to the project as well as their relationships with each other.

The PEP usually starts by providing the project background and the project objectives. The resource levels required to execute the project as well as the delivery timeline are also contained in the PEP. The PEP also presents the communication and consultation procedure required for the project as well as the stakeholder management plan. The PEP also describes the governance arrangement for the project during the execution stage including the policies and procedures that will be adopted. For example, the PEP will usually have a risk section that explains the agreed approach for risk management including details of the risk governance and reporting structure within the project. Table 2.2 provides an example of the content of the PEP.

• Project definition and a summary of the strategic brief or later the project brief

• Roles, responsibilities, and relationships

• Design drawings

• Government authority approvals, permissions, and consents approach

• Project schedule

• Cost plan, cost management procedures

• Risk management strategy

• Issue management plan

• Contracting and procurement strategy

• Monitoring and reporting strategy

• Stakeholder management plan

• Gateway review process: internal and external/funders (if appropriate)

• Communication plan

• Technology strategy

• Change management approach

• Health and safety strategy

• Sustainability strategy

• Quality assurance strategy

• Handover and project acceptance approach

When performance standards have been set through planning, the next step in the project control process is usually to monitor and report on actual performance. Monitoring is the process that provides information on all aspects of a project so that management can use the information to understand the status of the project based on deliberate actions as well as unplanned or unforeseen events on the project. Monitoring aims to determine whether the intended objectives have been met. In a project environment, monitoring involves the process that facilitates the checking and validation of a project’s performance metrics and comparison with the planned and predicted project’s metrics. The aim of project monitoring is to ascertain whether the project is progressing in accordance with the project’s plan while providing information that can then be used to forecast the possible status of the project in the future.

Reporting is closely intertwined with monitoring, but reporting is the communication aspect of monitoring. Reporting provides an account of the work accomplished at a stated date (usually the reporting period end date) and information on the predicted project’s key performance including cost and schedule. Reporting also highlights current and potential problems identified during monitoring and presents the management action underway to overcome the effects of the problems. The importance of effective and accurate reporting in the project control process cannot be overemphasized because the report is where the information collected during monitoring is contained and it is an analysis of the information that shows the status of the project.

The PCIM project control methodology research that informed this book has developed best practices for the monitoring and reporting steps of the project control process. These are presented in Chapter 6.

Analysis (Comparison and Evaluation)

After monitoring and reporting, the next step in project cost and time control is the analysis of the cost and time information contained in the submitted report. Having gathered the data, the team must determine whether the project is behaving as predicted, and if not, calculate the size and impact of the variances. The quantitative measures of progress are time, scope, and cost and so they receive significant attention during the project control process. The project control team will utilize the reports to forecast time and cost at completion and compute any difference (variance) between these figures and the baseline. The data and information from the monitoring process are then evaluated for any trends that may impact the performance of the project. Following this, analysis of the project’s progress is done to determine the effect of the latest reported and evaluated information on the project’s planned performance objectives. There are many techniques that can be used for the analysis steps of the project control process (details of the available project control techniques are presented in Chapters 7 and 8). However, it is important to point out that the main objective of analysis in project control is to identify proactively, potential negative trends that might hamper the achievement of the project objectives to prevent this negative event from coming to fruition.

The PCIM project control methodology research has also developed best practices for the analysis step of the project control process. These are presented in Chapter 6.

Action

To close the control loop, the team must take effective action to overcome any identified variance and deviation from the set project performance plan. The action step of the project control process is concerned with identifying and evaluating alternative courses of action for resolving a perceived problem situation. The objective of action is the development of a timely plan to mitigate problems affecting the project’s performance. To elaborate, the objectives of the action step in project control include the production of a recommended course of action, together with a statement of the implications of the action for the future of the project so that the project team and management will understand the consequential impact of the action should they decide to go for it. In practice, this action step may well involve an element of replanning, for example, carrying out a “what if” analysis that can then be used to evaluate implications for the future of the project.

Action closes the project control loop and if action is not taken when required the whole project control process is in vain. That is, just monitoring a project, knowing the performance, and reporting it to the relevant project stakeholders should not be mistaken with control. The control loop is only closed when appropriate action is taken and then continuing the control cycle by monitoring the impact of the action on the project. Actions need to be cost-effective and proportionate in relation to the issue they have been instigated to solve. Additionally, actions need to be timely so that they achieve their purpose but carried out in a controlled manner so that they do not create additional problems through careless implementation.