2 Work Breakdown Structure

The work breakdown structure (WBS) provides a framework for all project elements, for specific tasks within the project, and ultimately for better schedules and better estimates. A WBS will facilitate the process of integrating project plans for time, resources, and scope. A good WBS encourages a systematic planning process, reduces the possibility of omitting key project elements, and simplifies the project by dividing it into manageable units. If the WBS is used as the common skeleton for the schedule and for the estimate, it will facilitate communication among the project team members implementing the project.

The WBS is an exceptionally useful tool for project planning and monitoring, particularly if it is a deliverable-oriented structure. The information for a WBS is drawn primarily from the project objectives statement, historical files containing information on past projects, previous project performance reports, or any other files containing the original and final objectives of previous projects.

Rather than develop a WBS for each project, sometimes it is more convenient to develop a general WBS for a family of projects and then select and modify only selected segments for each project. This practice is appropriate in organizations that conduct projects that are somewhat similar but not necessarily identical.

The process of estimating the cost and duration of the project will also require a detailed and sophisticated resource breakdown structure (RBS). While the WBS is a methodical categorization of the deliverable’s components, the RBS is a logical and useful classification of the resources necessary to accomplish the project objectives with respect to those deliverables. Rather than developing a new RBS for each project, developing an RBS for a large family of projects may be more efficient. As each new project is planned, only those portions of this common RBS that apply to the project at hand will be selected and used.

A project RBS is different from all other human resource or budgeting classification methods in that it will reflect applicability to project management as compared to cost accounting or to personnel evaluations. An RBS is essentially a catalog of all the resources that will be available to the project.

Another readily available structure that is indirectly useful to project planning is the organizational breakdown structure (OBS). Because companies frequently go through massive organizational changes, care must be taken to use the most current data, keeping them current with frequent updates as changes continue to occur to the reporting lines of the organization. For the purposes of the project management system, the normal organizational chart must be augmented by those unwritten responsibilities and by those dotted-line relationships that affect the project’s execution. The OBS will be exceptionally useful in identifying project stakeholders, organizational objectives, and resource constraints.

A WBS is—or should be—a uniform, consistent, and logical method for dividing the project into small, manageable components for purposes of planning, estimating, and monitoring. The WBS is also a facilitative tool for communication between the team and the stakeholders, and among the team members. A WBS will provide a roadmap for planning, monitoring, and managing all facets of the project, such as:

• Definition of work

• Cost estimates

• Budgeting

• Time estimates

• Scheduling

• Resource allocation

• Expenditures

• Changes to the project plan

• Productivity

• Performance.

As the project is conceived, defined, and fully developed, not only can summaries for the WBS be created for one project, but departmental and divisional summaries also can be made for each WBS item. These summaries, which use the relationship between the WBS, RBS, and the resource expenditure profile, can be quite useful for resource forecasting, personnel projections, priority definitions among projects, assessing the performance of departments and divisions, and general management purposes.

WBS DEVELOPMENT STEPS

Simply stated, WBS development can be viewed as the process of grouping all project elements into several major categories, normally referred to as Level One; each one of these categories will itself contain several subcategories, normally referred to as Level Two. Alternately, and more accurately, developing a WBS involves dividing the project into many parts that, when combined, constitute the project deliverable.

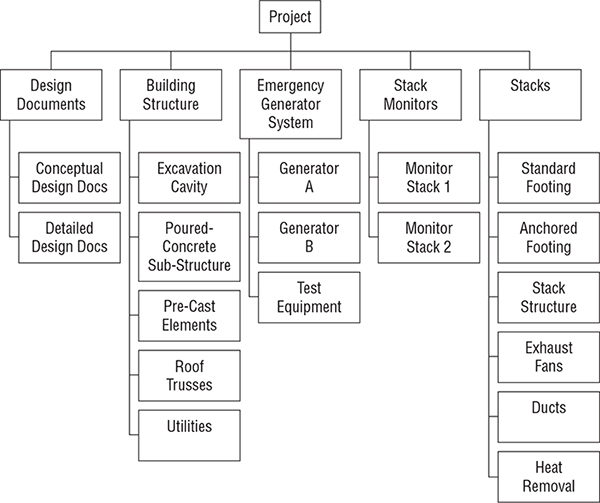

As a rule of thumb, the project is divided into several (three to nine) elements (see Figure 2-1). Then, each of the Level One elements will be divided into three to nine Level Two elements, each of the Level Two elements will be divided into three to nine Level Three elements, and so on. The ultimate goal is to formulate a detailed WBS that highlights a logical organization of products, parts, and modules.

This process of dividing the deliverable items continues until the project has been divided into manageable, discrete, and identifiable items requiring simple tasks to complete. A rule of thumb is to keep dividing the project until the elements cannot realistically be divided anymore. This point may vary from organization to organization and may even vary among project managers within the same organization.

The contents of each level of detail are not only organization-specific, but they also are specific to the nature of the deliverables involved in each project. Similarly, the degree of detail at the lowest level of each branch must be in line with the size of the project and in conformance with the organization’s operational philosophies.

Figure 2-1

Work Breakdown Structure

Ideally, there should be some uniformity and consistency in the WBS. To achieve this uniformity, all children of the same parent must be developed based on the same division basis.

Reasonable consistency should be maintained in the degree of detail at the lowest level elements. For example, if one branch describes the transmission of a car and the other branch describes the engine of the same car, the lowest levels should go either to subcomponents such as valves and sensors, or to more detail down to the metal screws. Not all branches need to go to the same level, but the significance of all of the lowest-level items in the overall project should be similar. Therefore, depending on the nature of the project, some branches may go to Level Two, some to Level Three, and some to Level Five.

Several WBS examples are included at the end of this chapter.

THE DIVISION BASES

The transition from each level of WBS to the next level may be based on any one of the following (see Figure 2-2):

• Deliverables

• Schedules

• Resources.

Figure 2-2

Work Breakdown Structure

In the deliverable-oriented mode, the product basis refers to those cases in which the project is divided into individual distinct components that ultimately comprise the project, such as hardware, software, physical structure, concrete foundation, or steel roof. The functional basis refers to the functional systems that provide a particular facet of the infrastructure for the project deliverable. Functional systems usually are interwoven into the product. Examples of functional systems include the electrical system, mechanical system, or skeleton of a building. In software and system development projects, these could be the verification module, data transfer module, backup module, and virus protection module. The physical-area basis highlights the geographical or physical locations of the deliverable (e.g., south side, north side, top floor, entrance). The most useful, and admittedly the most difficult, procedure for developing a WBS is to use the deliverable as the basis of breakdown of the project.

There is some overlap in definition and usage among the items of a subgroup of these nine bases, i.e., among product, functional system, and physical location. It is possible that someone would divide the project on the basis of product, and, depending on the nature of the project, someone else might view the division as having been on the basis of physical location.

For example, if the deliverables of a project included an industrial plan, one could divide the deliverables by functions, such as receiving, fabricating, polishing, packaging, and shipping. These operational functions use pieces of equipment that are distinct products, and operational design requires that each function be located in a specific area of the floor. Therefore, the division basis can be regarded as physical location basis also. Regardless of which of these subcategories is used, the deliverable basis of WBS development is far superior to the other bases, partly because it is customer-focused and partly because it has profound facilitation features during the project’s execution stages.

In the schedule-oriented mode, task or activity basis refers to things that project team members do toward accomplishing the goals of the project, such as excavating, pouring, forming, polishing, programming, and testing. Sequential basis reflects the order in which activities are performed, such as Phase I, Phase II, and Phase III. The sequence often is dictated by administrative constraints and is somewhat arbitrary.

Using these two bases is akin to importing the project schedule into the WBS. Ideally, the WBS should be used to develop the schedule, and not the other way around. There is no question that the lowest level of a fully developed WBS will comprise activities. However, it would be more useful if one of the deliverable-oriented bases were used for the majority of the upper portion of the structure.

Similarly, the resource-oriented basis is an infusion of the organizational structure into the WBS and will highlight the administrative or organizational division lines. Examples of discipline, or administrative-unit, basis elements are work done by employees of division A, division B, or the contract office.

The budget account basis is an infusion of the resource availability profile into the WBS and will follow the organization’s financial structure, such as activities paid by federal funds, state funds, charge account A, or fiscal account B. Here again, the WBS should be used to develop the cost accounts, costs estimates, and resource assignments, and not the other way around. The distinction is that funding procedures should not influence the nature of the project, just how the costs are disbursed.

COMPARISON OF THE DIFFERENT BASES

The most common and easiest method of developing the WBS is to use the task, activity, or phase as the basis of breakdown from one level to another. The vast majority of the elements in the vast majority of WBS fit this pattern. By and large, the project professionals that come from a scheduling background tend to use this basis as the breakdown basis. Notwithstanding, the deliverable-oriented bases, using any of the deliverable subcategories shown in Figure 2-1, are preferable.

One stated advantage for the schedule-oriented elements is that the resulting WBS can be used for many projects. Although this feature can be an advantage because the WBS is generic, the same feature also can be a disadvantage because it does not address the definitive features of the project in a clear and highlighted fashion.

Another feature of a schedule-oriented WBS, which sometimes has been perceived as an advantage, is that the WBS is applicable when the project is not fully defined. Unfortunately, this advantage also becomes a disadvantage when the project is fully specified, yet the estimating and scheduling of the project are still dependent on bundled categories for items such as design and testing.

Because ultimately projects are carried out when people do things such as develop, draw, print, fix, and fabricate, the elements at the lowest level always will be activity-based. However, using the deliverable methodology, the basis of division would change from schedule-oriented to deliverable-oriented as low in the WBS as possible. Alternately, different activities can be signaled by assigning resources that have appropriate titles or functions. For example, a lowest-level element can be tagged to design engineers, software programmers, and test engineers. Thus, without listing an activity-based WBS element, we have identified the activities involved with this element, namely, designing, programming, and testing.

The second most common basis for developing a WBS is the administrative basis. Those project professionals who come from a financial or administrative background tend to use disciplines, administrative units, or budget accounts as the basis of WBS breakdown. Although such bases would make tracking funds very simple and straightforward, they may not significantly help the project management objectives. The bases included in the resource-oriented group should be used as little as possible because they do not refer to the deliverable but rather to the means by which the work intended to produce the deliverable is administered and paid for.

Even if one chooses a schedule-based WBS, it is very important to make sure that the elements on the first several levels of the WBS, certainly those on Level One, are deliverable-oriented and not schedule-oriented or resource-oriented. That is not to say that activities and costs are not important. On the contrary, development, monitoring, analysis, and control of project schedule and project financing will be far more meaningful if a deliverable-oriented WBS that includes activities, or activity-referenced resources, at the lowest levels is used.

For example, if the testing tasks are late, it would be possible to determine that the complexity of testing Item BB has delayed the overall testing results. Similarly, if the design costs are significantly below budget, it would be possible to determine that an unexpected reduction in component design costs for item CC has caused this unexpected (and pleasant) reduction.

With minimal effort, deliverable-oriented elements can easily be developed for the top levels of the WBS for most projects. Beyond that, product-oriented projects can easily include deliverable-oriented WBS elements for most of the project, sometimes with the exception of the first or second levels. This methodical approach may initially require some extra effort for those project managers who have used schedule-oriented WBS in the past. Once using this methodology becomes second nature, deliverable-oriented WBS can be developed with ease. Process-oriented projects tend to have schedule-oriented elements for most of their WBS, certainly at the lower portion.

A deliverable-oriented WBS is most useful in projects in which it is more important to know the scope, cost, and duration of each delivered module rather than the activities that produced that module or group of modules. By contrast, a schedule-oriented WBS is more appropriate for cost-plus projects, for internal projects that have no work packages to contract, and for projects where the activities or the-step-by-step process is of utmost importance. Additionally, a deliverable-oriented WBS would facilitate and encourage the feed-forward of information within the project. (Feed-forward is a process by which the estimate of an element is refined by the performance of similar elements that were implemented earlier in the same project.)

PROCESS-ORIENTED PROJECTS

The point in the WBS at which the basis of division will change from deliverable-oriented to schedule-oriented depends on the nature of the project. If the project involves delivering a physical entity, most of the divisions and elements other than the lowest level can easily be described with deliverables. If the project is process-oriented, most of the elements will be activities.

A project is product-oriented if, at its end, a unique final product is delivered to the client, such as a car, an airplane, a building, an organizational structure, or a set of design documents. By contrast, a process-oriented project is somewhat repetitive, such as running a lumber mill, a refinery, or a contamination cleanup project. In these cases, the project resembles a checklist of objectives that must be estimated and scheduled. Even in these projects, someone fully conversant with the deliverable WBS can develop deliverable elements.

It is difficult—although not impossible, and certainly advisable—to develop deliverable-oriented elements for the top levels of the WBS for most of the process-oriented projects. The difficulty in developing a deliverable-oriented WBS is minor for projects that involve physical results, and the difficulty can be significant for process-oriented projects.

Sometimes, the distinction between a product-oriented project and a process-oriented project is determined by testing whether or not the project activities have become somewhat standardized in developing replicas of the deliverable of the first project. To illustrate, designing and building the first supersonic jumbo jet is a product-oriented project. However, manufacturing each of the next 245 planes is a process-oriented project.

In some projects, in which the physical deliverables are minimal or not commonly recognized as deliverables, the majority of elements are schedule-oriented. Examples of these projects are cleaning up a contaminated site, demolishing a building, excavating the cavity for a building foundation, or removing a software virus from a computer program. With some effort, a deliverable-based WBS can be crafted even for these projects. For example, the deliverable items can be reports of test results for thickness, contaminants, texture, or color. Likewise, the deliverables can be reports of test results for error rate, customer satisfaction, processing speed, and transmission speed.

Additional examples of product-oriented projects are:

• A new bank

• A new laboratory

• A new manufacturing plant

• A new software package

• A software upgrade

• A unique facility design.

By contrast, examples of process-oriented projects are:

• Conducting the annual closeout at a bank

• Converting chemicals into plastics

• Converting crude oil to gasoline

• Performing annual turnaround or maintenance for factories and plants

• Manufacturing a batch of chemicals

• Monitoring productivity at Site G

• Issuing monthly payroll checks.

ORGANIZATIONAL PRIORITIES

Sometimes there is a tendency to add items to the WBS that do not represent deliverables but that are activities that are part of the organizational priorities and imperatives. The intent of including such items in the first level of WBS is to signal conformance with the organizational imperatives or to maintain organizational harmony. Examples of items that often find their way to the first level of WBS are:

• User support

• Purchasing

• Integration

• Systems engineering

• Value engineering

• Contract process

• Project monitoring

• Project management

• Budget approval

• Project closeout

• Design process.

The rationale for not including these items at Level One is twofold. First, it would distort the deliverable basis of division at Level One; Level One would be fully deliverable without this activity element, and a hybrid of sorts with that activity. Second, and more important, placing such activities at Level One would detract from the accuracy of the plans and would thus destroy the sharp focus necessary for monitoring the schedule and cost. With some amount of care, these items either can be rolled into the overhead cost of the project or they can be tagged to individual lowest-level elements, or activities, as resources—that is, of course, if there is no overriding organizational need to highlight these elements.

An example of such a WBS modification was observed during the WBS development for a project with the objective to deliver a computer system to a customer. This project involved providing software and hardware to the client at the end of the project. The elements of this WBS were deliverable-oriented through Level Four (see Figure 2-3). The Level One WBS items were:

• Hardware

• Software

• System documents.

After the WBS was developed, the divisional manager instructed the project manager to add user support as a Level-One element. The reason was that, at the time, the organization was making a transition toward more user-friendly systems development. Inserting user support as a first-level WBS item was intended to recognize and highlight this priority. Therefore, the Level One elements of this systems development WBS became (see Figure 2-4):

Figure 2-4

WBS Organizational Priorities Added

• Software

• System documents

• User support.

The disadvantage of listing these activities as Level One items is that they become freestanding activities that seemingly are not associated with any specific product. The amorphous nature of the task also makes it difficult, if not impossible, to monitor and control the resource expenditures with any reasonable accuracy. Certainly, these activities are needed to deliver the products that are listed on Level Three or Level Four of the WBS, and they need to be listed as such.

Moreover, even if these activities are listed at lower levels, they can be summarized with equal ease across WBS structures and across resource structures. The only difference is that, using a fully deliverable structure, they are not highlighted at Level One of the WBS. Admittedly, listing these activities at Level One might afford very high visibility to the upper management for these activities, primarily because upper management usually gets to see only the first two levels of the WBS. Again, such augmentation of the WBS distorts the logical structure of the WBS and therefore is not recommended.

SEMANTICS

Using vague words or words with multiple meaning in WBS titles can cause confusion and misunderstandings in interpreting and planning the WBS items. For example, if a WBS item is labeled “procurement,” it could refer to the people who buy things, the department that employs them, or the process of buying things. Similarly, if a WBS item is labeled “mechanical,” it could refer to the mechanical engineering design process, the mechanical portion of the deliverables, the mechanical engineers, or the department that employs them. If a WBS item is labeled “system,” it could refer to the system that is delivered to the client, the software portion of the system, the people who write the software, the department that employs them, or the process of writing software (see Figure 2-5).

Admittedly, most of the time the likelihood of confusion and misunderstanding is minimized if these words are interpreted within the appropriate context. However, the project planner must make every effort to eliminate all potential causes of confusion from the project plans.

As an illustration, consider a project that is described by the following WBS components: procurement, systems, civil, mechanical, and legal. These elements could be interpreted as uniformly referring to disciplines, administrative units, activities, or a combination of the above (see Figure 2-6). If there is a possibility of ambiguity in naming the WBS elements, qualifiers such as “mechanical engineering department,” “civil engineers,” “Procurement Phase II,” “software module,” “mechanical drawings,” or “contract documents” should eliminate any confusion.

CHANGING THE PARADIGM

A WBS sometimes can be changed from schedule-oriented to deliverable-oriented by modifying and changing the wording of some elements. However, the transition from a schedule oriented WBS to a deliverable-oriented WBS is not simply effected by using non-action words; rather, it involves looking at the project from the standpoint of the client. Thus, the WBS would include the elements that the client is interested in receiving and those that the client will pay for.

Figure 2-5

WBS Complications

One way of highlighting the deliverable-oriented basis is to emphasize that the deliverable-based approach is client-centric and not project team-centric. As the WBS is developed, therefore, the project management professionals should be careful not to infuse details of how the work will be delivered into the description of the deliverable itself.

Once a deliverable-oriented WBS is established, if the client changes the scope and schedule constraint of various project modules, it is very easy to determine and justify the impact of such changes on the cost and schedule of the project. The reason is that planning a project with a deliverable-oriented WBS is conducted by planning specific items that make up the project, and not by planning a bundle of generic activities involved in delivering those items. Equally important, when the time comes to make those inevitable changes to the project plan, they can be made more accurately and logically with the use of deliverable items because the changes will be reflected only in those items that are affected.

The transition from a schedule-oriented WBS to a deliverable-oriented WBS may be difficult for those who have developed schedule-oriented WBS for a significant amount of time. The transition should be guided by a change in mindset from team-centric to client-centric. The focus should be on project objectives and specifications rather than on the activities of the team.

In cases in which the project objectives are not fully developed at the time the WBS is crafted, only the first two or three levels of the WBS can be developed. Later, as more project information becomes available, the WBS can be expanded and refined. Actually, this is a major advantage because it highlights the organic nature of the project plans.

Conceptually, the process of developing a deliverable-oriented WBS is relatively simple. One would divide the project into components that, when combined, would produce the final project deliverable. Ideally, one should avoid converting elements to activities and tasks until the last one or two levels of the WBS. The emphasis should be on describing the components that produce the project, the modules that produce the component, the units that produce the module, etc.

Additionally, one should avoid listing (as part of the WBS structure) the personnel responsible for delivery of reports, evaluations, or products. Such resource assignments can be done easily and systematically once the WBS and RBS are established, preferably independently of each other. An effective way to achieve this is to develop an RBS before starting to divide the project objectives, so that the project planner will not be distracted by resource issues during WBS development.

The following is the first level of a WBS that was developed using the traditional schedule-oriented mindset (see Figure 2-7):

Level One

• Conceptual design

Figure 2-7

Schedule-Oriented WBS

• Design

• Installation and checkout

• Removal of old equipment

• Project closeout.

Because a schedule-oriented WBS tends to be entirely activity-based, it is very difficult if not impossible to discern what the objective of the project is and what its deliverables are. Although not clearly identified in the WBS, the objective of this project is to deliver the following:

• Two new emission stacks

• New emissions monitoring system

• Emergency power building.

Accordingly, a deliverable-based WBS could be constructed along the lines of the following (see Figure 2-8):

Level One

• Design documents

• Building structure

• Emergency generator system

• Stack monitors

• Stacks.

This WBS clearly describes what the client should expect from the project manager or the contractor when the project is finished. Accordingly, tracking the project’s progress would be relatively simple by noting the progress of the delivery of the project’s components.

Figure 2-8

Deliverable-Oriented WBS

This example illustrates that with the deliverable-oriented WBS, one can easily and clearly plan the components of the project as a prelude to an informed process for monitoring the progress of the project’s components. One gets a clear idea of the project objectives and what is involved in achieving them. A deliverable-oriented WBS is easier to schedule, estimate, and monitor. Depending on the size of the project and the traditions of this particular environment, either the next level of activities would be schedule-oriented elements, or the element would be tagged to use activity-specific resources.

EXAMPLE

The following example illustrates use of the deliverable-oriented and the schedule-oriented bases for a fictional industrial complex (see Figure 2-9). The division of elements at different junctures has been performed using different bases.

• Power House

– Steam generation system

– Electrical generation system

– Electrical transmission system

• Factory

– Receiving equipment

– Processing equipment

– Packaging equipment

– Shipping equipment

• Office

– First floor

– Second floor

– Penthouse

• Grounds

– Phase One: bushes and trees

– Phase Two: seeding for lawn

– Phase Four: parking lot.

In this example, the breakdown basis for Level One is physical location; for the powerhouse, functional system; for the factory, product, physical location, or functional system; for the office, physical location; and for the grounds, sequential. If this project were to be implemented, a new all-deliverable WBS could and should be developed.

Work Breakdown Structure Examples

Bank Data Conversion Software Project

Wireless Communications Project

Branch Network Restructuring Project

Industrial Construction Project

Home Building Project

Deliverable Work Breakdown Structure

0.0. Residential House

1.0 Project Documents

1.1 Contractual Documents

1.1.1 Proposal

1.1.2 Quotation

1.1.3 Contract

1.2 Drawings

1.2.1 Architectural Drawings

1.2.2 Civil Drawings

1.2.3 Electrical System Drawings

1.2.4 Mechanical System Drawings

1.3 Permits

1.3.1 Zoning

1.3.2 Labor

1.3.3 Building Inspection

1.4 Project Controls

1.4.1 Schedule

1.4.2 Cost Estimate

1.4.3 Risk Management Plan

2.0 Project Supplies

2.1 Raw Materials

2.1.1 Architectural Finish Materials

2.1.2 Civil Structure Materials

2.1.3 Electrical Systems Materials

2.1.4 Mechanical Systems Materials

2.2 Manufactured Components (machines, parts, etc.)

2.2.1 Architectural Equipment

2.2.2 Civil Structure Equipment

2.2.3 Electrical Systems Equipment

2.2.4 Mechanical Systems Equipment

2.3 Specialty Equipment

3.0 Project Edifice (the “house”)

3.1 Civil Structure

3.1.1 Land

3.1.2 Foundation

3.1.3 Superstrucutre

3.1.3.1 Floors

3.1.3.2 Framing

3.1.3.3 Roof

3.2.1 Potable Water System

3.2.2 Sewage System

3.2.3 HVAC Systems

3.2.4.1 Heating

3.2.4.2 Air Conditioning

3.2.4.3 Ventilation

3.3 Electrical Systems

3.3.1 Electricity Distribution System

3.3.2 Phone/LAN Lines

3.3.3 Fire Detection System

3.3.4 Home Security System

3.4 Architectural Finishes

3.4.1 Basement

3.4.2 First Floor

3.4.3 Second Floor

3.4.4 Exterior

Hardware Design Project

Work Breakdown Structure

0.0 ABC123 Integrated circuit database

1.0 Circuit design schematics

1.1 Base-level Schematics

1.1.1 Multiplexer 1

1.1.2 Multiplexed

1.1.3 Rotational frequency detector

1.1.4 Variable controlled oscillator

1.1.5 Digital/analog converter

1.1.6 Counter l

1.1.7 Counter 2

1.2 Block-level Schematics

1.2.1 Equalizer

1.2.2 CDRPLL

1.2.3 Transmitter PLL

1.2.4 LVDS driver

1.2.5 Decoder

1.2.6 Encoder

1.2.7 Cable driver

1.3 Top-level schematic

2.0 Mask Design cells

2.1 Base-level cells

2.1.1 Multiplexer 1

2.1.2 Multiplexed

2.1.3 Rotational frequency detector

2.1.4 Variable controlled oscillator

2.1.5 Digital/analog converter

2.1.6 Counter l

2.1.7 Counter 2

2.2 Block-level cells

2.2.1 Equalizer

2.2.2 CDR PLL

2.2.3 Transmitter PLL

2.2.4 LVDS driver

2.2.5 Decoder

2.2.6 Encoder

2.2.7 Cable driver

2.3 Top-level cell

3.0 Documentation

3.1.1 Product requirement specification

3.1.2 Intellectual property plan

3.1.3 CAD and design library development plan

3.1.4 Project risk analysis

3.1.5 Design FMEA

3.1.6 Business case

3.1.7 Buildsheet

3.1.8 DRC/LVS report

3.1.9 Patent applications

3.1.10 Final design review

3.2 Supplemental design documents

3.2.1 Intermediate circuit design reviews

3.2.1.1 Equalizer

3.2.1.2 CDRPLL

3.2.1.3 Transmitter PLL

3.2.1.4 Multiplexer

3.2.1.5 Multiplexed

3.2.1.6 LVDS driver

3.2.1.7 Decoder

3.2.1.8 Encoder.

3.2.1.9 Cable driver

3.2.2 Mask design reviews

3.2.2.1 CDRPLL

3.2.2.2 Transmitter PLL

3.2.2.3 Cable driver

3.2.2.4 Equalizer

3.2.2.5 Top-level floorplan review

3.3 Miscellaneous documents

3.3.1 Weekly project review

3.3.2 HSPICE model

3.3.3 DFT analysis

Terms:

Buildsheet |

A document that graphically represents the package assembly requirements for a specific integrated circuit. Package DRCs are performed while generating this document. |

CDR PLL DFT |

Clock/Data Recovery Phase-Locked Loop Design for testability. A DFT analysis is performed on the circuit to decide if additional circuitry is needed to enable various aspects of the circuit’s functionality to be verified once the physical IC is being produced. |

Design Rules Check/Layout vs. Schematic. Failure Mode Effects Analysis Software used to generate models of a circuit that customers can use to integrate into their system design model to test functionality. |

|

LVDS NIBU |

Low Voltage Differential Signal Network Interface Business Unit, a business unit within the Wired Communications Division of National Semiconductor. |

NPPRS |

Network Interface Business Unit’s New Product Phase Review System is the structured stage-gate process utilized to develop new products, in which the deliverables at each phase are clearly defined. |

Weekly Project Review |

Due to the duration of the design portion of this project, weekly project reviews are generated for middle and upper management and the team. The reviews encompass all nine areas of project management as shown in the RBS. |

Health Services Project

Work Breakdown Schedule

Outpatient Occupational Therapy Center—Work Breakdown Structure

1 Facility

1.1 Location

1.1.1 Site

1.1.2 Leasing contract

1.1.3 Possession

1.2 Interior

1.2.1 Office

1.2.1.1 Information desk

1.2.1.2 Individual office space for employees

1.2.1.3 Records library

1.2.2 Occupational Therapy Department

1.2.2.1 Diagnostic and Evaluation rooms

1.2.2.1.1 Area for physical evaluation

1.2.2.1.2 Area for neurological evaluation

1.2.2.1.3 Area for cognitive evaluation

1.2.2.1.4 Area for pediatric evaluation

1.2.2.2 Therapeutic rooms

1.2.2.2.1 Area for physical therapy

1.2.2.2.2 Area for neurological therapy

1.2.2.2.3 Area for cognitive therapy

1.2.2.2.4 Area for pediatric therapy

1.2.2.3 Rehabilitative rooms

1.2.2.3.1 Area for physical rehabilitation

1.2.2.3.2 Area for neurological rehabilitation

1.2.2.3.3 Area for cognitive rehabilitation

1.2.2.3.4 Area for pediatric rehabilitation

1.2.3 Miscellaneous

1.2.3.1 Waiting area

1.2.3.2 Kitchen

1.2.3.3 Restrooms

1.3 Exterior

1.3.1 Security system

1.3.2 Access to physically handicapped

1.3.3 Billboard of facility name

2 Personnel

2.1 Occupational therapy professionals

2.1.1 Registered occupational therapist

2.1.2 Certified occupational therapy assistant

2.1.3 Occupational therapy counselor

2.1.5 Medical assistant

2.2 Support Staff

2.2.1 Social worker

2.2.2 Home health aide

2.2.3 Nursing aide

2.2.4 Equipment maintenance specialist

2.2.5 Maid and housekeeper

2.2.6 Security guard

2.2.7 Financial advisor for patients

2.3 Administrative Staff

2.3.1 Receptionist and information desk clerk

2.3.2 Administrative assistant

2.3.3 Accountant

3 Licenses

3.1 Business

3.2 Registered occupational therapist

3.3 Certified occupational therapy assistant

3.4 Registered nurse

3.5 Software

4 Insurance

4.1 Business

4.2 Registered occupational therapist

4.3 Certified occupational therapy assistant

4.4 Registered nurse

4.5 Warranties and insurance on equipment

5 Operations

5.1 Maintenance

5.1.1 Inventories

5.1.2 Equipment

5.1.3 Housekeeping

5.2 Human Resources

5.2.1 Payroll services

5.2.2 Employee benefits

5.2.3 Continued recruiting

5.3 Client Services

5.3.1 Administrative

5.3.1.1 Appointments

5.3.1.2 Paperwork

5.3.1.3 Insurance claims

5.3.2 Therapeutic

5.3.2.1 Diagnosis and evaluation

5.3.2.2 Therapeutic or rehabilitative treatment

5.3.2.3 Follow-up

Bank Data Conversion Software Project

XYZ Corporation Global Services Conversion Services Contracted Core Banking Data Conversion

Objectives

This project provides data from an acquired bank converted to a format that allows merging of the data into the client’s applications. The project includes needs assessment, application and process design, implementation, and creation of the converted files and reports for client testing.

Work Breakdown Structure

0. Banking Data Conversion

1.0 Functioning Environment

1.1 Project Execution Environment

1.2 Host System Environment

1.3 Remote Network Environment

1.4 Workstation Environment

2.0 Needs Analysis Documentation

2.1 Source System Analysis Report

2.2 Source Data Dictionary

2.3 Source Data Analysis Report

2.3.1 Customer Information File Analysis Report

2.3.2 Name & Address Scrubbing Analysis Report

2.3.3 Account File Analysis Report

2.3.4 Account History File Analysis Report

2.3.5 Pre-Authorized Transaction File Analysis Report

2.3.6 Product Definition Table Analysis Report

2.4 Target System Analysis Report

3.0 Design Documentation

3.1 Overall Solution Approach Document

3.2 Product Definition Report

3.3 Target Record Layout Definition

3.4 Detailed Schedule of Mapping Sessions

3.5 Mapping Specifications

3.5.1 Customer Information File Specs

3.5.2 Account File Specs

3.5.3 Account History File Specs

3.5.4 Pre-Authorized Transaction File Specs

3.5.5 Product Definition Table Specs

3.6 Balancing Documentation

3.7 Solution Approach Document

3.8 Loader Program Design Document

4.0 Software and Execution Forms

4.1 Data Conversion Applications

4.1.1 Customer Information File Application

4.1.2 Account File Application

4.1.3 Account History File Application

4.1.4 Pre-Authorized Transaction File Application

4.1.5 Product Definition Table Application

4.2 Prove Reports

4.2.1 Customer Information File Application

4.2.2 Account File Application

4.2.3 Account History File Application

4.2.4 Pre-Authorized Transaction File Application

4.2.5 Product Definition Table Application

4.3 Data Loader Application

4.4 Conversion Supporting Data

4.4.1 Audit Trail Application

4.4.2 Balancing Spreadsheet Definition

4.4.3 Exception Report Definition

4.4.4 Conversion Job & Activity List

5.0 Converted Files and Reports

5.1 Load-Ready Files

5.2 Balancing Sheets

5.3 Load Data Analysis Report

5.4 Exception Report & Audit Trail File

6.0 Project Completion Analysis Report

Wireless Communications Project

Upon completion of the relocation, a new RFT will be located in Las Vegas, all customer netgroups will be up and running in the new facility, and customer backhaul networks will be installed and functional. The Los Angeles facility will be returned to the landlord according to the conditions of the lease.

0.0 Relocation of Los Angeles Shared Hub Facility

1.0 Equipment

1.1 RFT Equipment

1.1.1 New Indoor Equipment

1.1.2 Old Indoor Equipment

1.1.3 New Outdoor Equipment

1.1.4 Old Outdoor Equipment

1.1.5 New Cabling

1.1.6 Old Cabling

1.2 Baseband Equipment

1.2.1 Spare NG A/B

1.2.2 NG1/2

1.2.3 NG3/4

1.2.4 NG5/6

1.2.5 NG7/8

1.2.6 NG 9/10

1.3 Backhaul Equipment and Lines

1.3.1 Hub Routers

1.3.2 Customer Routers

1.3.3 T-Lines

2.0 Facility

2.1 Las Vegas

2.1.1 Land

2.1.2 Antenna Foundation

2.1.3 Building Infrastructure

2.2 Restoration of Los Angeles

2.2.1 Restore-Land

2.2.2 Restore-Foundation

2.2.3 Restore-Building Infrastructure

3.0 Documentation

3.1 Project Controls

3.1.1 Schedule

3.1.2 Cost Estimate

3.1.3 Risk Management Plan

3.2 Drawings/Plans

3.2.1 RFT Design

3.2.2 Baseband Design

3.2.3 Backhaul Design

3.2.4 Facility Design

3.3.1 Zoning

3.3.2 Labor

3.3.3 Environmental Approval

4.0 Personnel

4.1 Staffing Plan

4.2 Relocation Plan for existing personnel to Las Vegas

4.3 Training

Branch Network Restructuring Project

Work Breakdown Structure

Deliverable Oriented

PROJECT’S OBJECTIVES STATEMENT

Design and implement a new salary, incentive, and responsibility structure for the branch network positions that recognizes and rewards employees for their role in the organization and for contributing to the bank’s success.

Industrial Construction Project

Graphical Work Breakdown Structure

This chapter is an adaptation of a paper by Parviz F. Rad, “Advocating a Deliverable-Oriented Work Breakdown Structure,” that was originally published by AACE International in Cost Engineering, Volume 41, Issue 12, December 1999. Reprinted with the permission of AACE International, 209 Prairie Ave., Suite 100, Morgantown, WV 25601, USA. Phone 800-858-COST/304-296-8444. Fax: 304-291-5728. Internet: http://www.aacei.org. E-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © by AACE International; all rights reserved.