6 External Projects

For strategic reasons, organizations sometimes choose to acquire outside resources for a project. This process is called “outsourcing” or “contracting.” The decision to outsource is primarily dependent on the organization’s strategic objectives and is based on factors such as competencies of the prospective internal team and the infrastructure characteristics of the division sponsoring the project. Other contributing factors include market conditions and the organization’s competitive aspirations.

Some organizations opt for external projects to gain immediate access to specialized skills or equipment. Others even use external projects as subtle mechanisms for transforming the culture of the organization. Finally, some organizations argue that external projects are less costly to the organization.

The disadvantage of outsourcing is that the organization will not have the opportunity to improve and enhance its own operational capability and competency. Further, the company might lose direct involvement in, and control over, execution of the project. A very important issue is that an external project might jeopardize the trade secrets and the proprietary details of the organization’s best practices.

An undesirable side effect of outsourcing is that it tends to have a self-perpetuating effect on the organization, primarily because often there will be very little, if any, institutional memory from the project’s execution. Therefore, the stage is set to have future projects in an outsourced mode also. Finally, the cost of executing projects outside the company can sometimes be higher if both the tangible and intangible costs are considered.

In rare cases in which the client forms partnerships with the contractor for the purposes of the project, the potential contractor is encouraged to behave as part of the same team with the client and is rewarded for behaving in the best interest of the project, although that sometimes appears to be at odds with the short-term interests of the contractor. In such cases the client tends to reap the benefits of the contractor’s experience and dedication, while the contractor is allowed to earn a reasonable return on investment.

External projects often pressure the client to be more specific in defining the physical attributes and performance expectations of the final project deliverable. Ironically, it is often the scarcity of competency in the subject technical area of the project that provides the primary impetus for resorting to external projects. Therefore, providing a detailed articulation of objectives and specifications by the client might become an impossible task. As a result, in the first phase of project implementation, the contractor will need to develop the project specifications by interpreting the client’s objectives.

SPECIFICATIONS

A detailed definition of the scope and objectives of the project is normally used when planning and implementing a project. Such detailed and formal specifications are frequently drafted only for external projects. However, for purposes of cost management and organizational memory, developing and maintaining specifications for internal projects as well as external projects is useful. Project specifications are included in the contract for external projects and in the authorization memo for internal projects.

Ideally, project specifications will highlight what will be delivered to the client once the project is completed. It will be less useful if the project specifications outline the activities of the project without any major emphasis on the deliverables.

The specifications documents are the most formalized articulation of the wishes and desires of the client and should include all the technical data necessary to plan and implement the project. They should provide details of all those items that are needed or desired, as well as all those that are considered undesirable or unacceptable. Further, the specifications should outline those items that are necessary for the success of the project but will be fabricated, developed, or delivered by the efforts of another project. Finally, the specifications might outline details of materials, equipment, services, procedures, and tools that should be used for the project.

The detailed information for project specifications is presented in written, tabular, and graphic formats. To some extent, the choice of the format is dictated by the nature of information. For example, graphic format is most efficient in conveying the arrangement, size, and location of physical components, while spreadsheets and tables would be the appropriate method for portraying numerical relationships. Naturally, text is most appropriate for depicting verbal description of objectives, activities, performance criteria, and strategic issues.

It is very difficult, if not virtually impossible, to produce complete and flawless specifications, as evidenced by the revisions that are issued to many contract documents even as early as during the bidding process. Therefore, you should anticipate that the specifications will change, to some extent, during the life of the project. These changes include clarifications of and modifications to the project’s scope, quality, expected cost, and desired duration. As the project evolves, these changes should be reflected in the WBS, the specifications, and other planning documents.

To facilitate comprehension of and compliance with the specifications, all facets of the project deliverables must be quantified, to the extent practicable. Accordingly, attempts should be made to quantify deliverable qualifiers such as user-friendly, robust, smooth, and aesthetically pleasing.

There are three types of specifications: focused design, generic performance, and functional. Focused design, or product, specifications provide details of what is to be delivered in terms of physical characteristics, or in terms of detailed tasks intended to contribute to a product or a service. An example of this type of specification is when the client provides details of how web pages should be designed, what graphics should be used in the various web pages, and how many records the database should contain. As such, the risk of performance and applicability rests directly with the client (see Figure 6-1).

If the specifications are drafted with performance, or generic, characteristics in mind, they define measurable operational capabilities that the deliverable must achieve. An example of this type of specification is when the client spells out the access speed, error rate, and general linkage characteristics of the website. The project team will then draft plans that will have the proper technical features so that the deliverable will satisfy the client’s performance expectations. Naturally, the risk of performance is borne by the project team, while the risk of applicability is borne by the client (see Figure 6-2).

Figure 6-1

Focused Design Specifications

![]()

Figure 6-2

Generic Performance Specifications

Functional specifications are usually the most logical mode of responding to the “wants and needs” of the client. However, they burden the client with the task of defining, in very clear terms, the basic objective of the final product. At the same time, this mode of specification development will empower the project team to use creative and innovative techniques to meet or exceed the client’s expectations (see Figure 6-3).

An example of this type of specification is when the client provides the contractor with the general business plan and the expected business outcome. The contractor then will develop a set of detailed plans and specifications that will enable the project to meet those business needs. Under this mode of operation, it is entirely possible that the contractor will communicate the specifications to the client, but that is usually just to keep the client informed and not necessarily for approval purposes.

In some cases, the client and the project team collectively develop project specifications. In other cases, such as in software and system development projects, the implementation team develops the project specifications by interpreting and analyzing the client’s needs and objectives. As much as such collaboration is very useful, it has the risk of blending project specifications with project implementation details and with project scheduling techniques.

This practice also blurs the line between the client’s goals and the project team’s objectives. Analyzing and evaluating the causes of cost and duration overruns can be very difficult if there is an overlap between client-generated material and contractor-generated material.

Figure 6-3

Functional Specifications

Finally, cost and duration overruns usually are accompanied by a gradual change in project scope, thus complicating the identification of a logical baseline for the project. If the scope changes are not documented, or if they are not managed in a formalized and consistent fashion, one more level of difficulty will be added to the task of managing the resulting cost impact of the schedule and scope changes to the project.

This continuous shifting of the baseline is sometimes referred to as scope creep. Scope creep is endemic in projects that are conducted as cost plus or in organizations that have very few original project objectives, or in projects whose plans and specifications have been formulated on the basis of objectives that can be characterized as “fuzzy.” However, it is fair to say that a certain amount of scope modification should be expected in most projects, both external and internal.

CONTRACTS

Although many external projects are initiated with the execution of a contract, and although many projects will need contracts to acquire resources and deliverables, a project should be treated as the legal instrument by which an organization acquires products and services from an outside source. For the purposes of managing a successful project, a contract is considered an administrative mechanism by which the project is conducted by personnel who reside outside the corporate boundaries of the client organization (see Figure 6-4).

Figure 6-4

Contract (Casual Definition)

![]()

Even when the project would not exist if it were not for the contract, the contract can be viewed as an expanded and highly formalized adaptation of the project charter. Notwithstanding, to define the responsibilities and rewards of both parties, a contract must conform to the legal definition of a contract, as shown in Figure 6-5. It is in the light of these considerations that a contract is drafted, signed, and enforced. The contractor’s offer is called a bid and, when chosen for the job, is referred to as the winner of the contract.

Contract documents for a project are composed of two major parts: administrative and technical. The administrative part deals with the legal responsibilities of both parties and with processes and procedures for enforcing the various contract clauses. The second part deals with the technical content of the project. This part of the contract is—or should be—the most important part to the project team, since it spells out the specifications, performance expectations, and delivery constraints of the deliverable (see Figure 6-6).

There are two basic forms of project contracts, as shown in Figure 6-7. The first type is called fixed price or lump sum. This type of contract requires detailed specifications. Usually, the contractor who offers the lowest price will be chosen for that particular project. In this mode of contracting, the prospective contractor offers to deliver the project deliverables for a fixed price. The contractor guarantees the fixed price and thus assumes all financial risk in implementing that project—that is, of course, if the initial set of client objectives and project specifications are spelled out with sufficient detail and if the project environment remains reasonably stable during the life of the project. Under ideal circumstances, this type of contract gives the contractor full incentives to avoid waste, to reduce costs, and to increase profits (see Figure 6-8).

Figure 6-5

Contract (Legal Definition)

Figure 6-7

Types of Contracts

![]()

Again, the lump sum contract is most appropriate for projects with precisely outlined scope and specifications that have little chance of changing (see Figure 6-9). If there are midstream changes to the scope and specifications, the contract will be modified to reflect a new price. The new price, and other conditions of the contract, will be negotiated between the contractor and the client at the onset of these changes in the project environment. The advisability of the lump sum type of contract will come under scrutiny during, and as a result of, these contract modifications.

The second type of contract is called cost plus, or time-and-materials. In this form of contracting, the contractor is selected on the basis of technical capability as well as on the basis of charging the lowest amount of money per unit of labor, equipment, overhead, and materials. The owner then directs the contractor to perform the various tasks of the project, while the contractor is paid for actual expenditures in accordance with the client’s instructions (see Figure 6-10), plus a fee. The reimbursable costs include labor, equipment, materials, and possibly service and supply subcontracts.

![]()

Figure 6-9

Characteristics of Lump-Sum Contract

In construction and industrial projects, there is a third basic form of contracting, which is called unit price (see Figure 6-11). This form is a mixture of the two basic forms described above. In effect, unit price represents a fixed price for a small element of the project. Under this type of a contract, the contractor submits a bid for each of the many small elements of the project. Then the contractor gets paid for the number of these units that are used for the project. Examples of unit pricing elements include one specific test using one specific testing machine, one line of code, one web page, one yard of concrete, one module of training, one hour of an engineer, and one hour of a programmer.

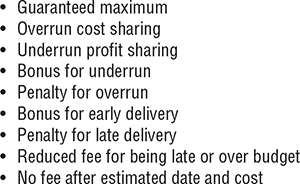

Experience has shown that these basic forms of contracting do not address challenges that present themselves during the life of the projects, such as scope changes, environmental changes, and design changes. Consequently, organizations award contracts that use one of the basic forms with modifiers that reward or restrict the behavior of the contractor. Examples of these modifiers are shown in Figure 6-12.

Figure 6-10

Characteristics of Cost-Plus Contract

Figure 6-11

Types of Contracts

Modifiers are intended to give the client the flexibility to modify the project specifications midstream in a way that has the lowest possible impact on project cost and duration. They are also intended to provide incentives to the contractor to be efficient, responsive, and exceptionally mindful of the best interests of the client—not to the exclusion, of course, of the contractor’s objectives of receiving the highest possible return on investment.

Figure 6-12

Contract Modifiers (for Cost-Plus or Unit-Cost Contracts)

The contract management procedures should outline the process for developing specifications, selecting contract type, and source selection. Additionally, these procedures should outline procedures for monitoring the contractor’s performance within the boundaries established by the contract and in light of the project’s technical objectives. While contract management planning documents should include procedures and policies to ensure contract compliance, they also should afford a reasonable amount of flexibility for minor changes in the deliverables.

RESPONSE TO SPECIFICATIONS

The role of specifications is minimal in cost-plus contracts, and there is no need to develop them fully during the contract award phase because the contractor will be paid based on how much time and effort is spent rather than on what is produced. In most cases, a cost-plus contractor is chosen on the basis of perceived capability and potential reliability, and not necessarily on a promised total cost or delivery date. Given the nature of the cost-plus contracts, sometimes the first assignment of the contractor is to develop the specifications and estimates for the project, and it is almost certain that the same contractor will implement the resulting specifications.

On the other hand, the role of specifications is pivotal in fixed-price contracts because the specifications will form the basis for the estimate, bid, and eventual award. Modifying a fixed-price contract midstream is difficult, time-consuming, and potentially expensive. Therefore, fixed-price contracts should be awarded only if the specifications are exceptionally accurate and if the probability of changes in the specifications is extraordinarily low.

When reviewing specifications, the project manager must make every effort to understand all of the client’s objectives and underlying reasons for wanting particular facets of the deliverable. Then, the project manager must make every effort to meet all the needs of the client cost-effectively. Ideally, this philosophy should be the guiding light for all types of projects because it fosters client-contractor partnership and trust.

Unfortunately, this philosophy is not practiced widely in contracting environments because it subtly affects the contracting strategy, bidding outcomes, and award circumstances. Although implementing such a congenial and trusting environment is possible, it must be approached with some sensitivity to the fact that the obligations and the reward system for the contractor personnel and client personnel, as delineated by the contract, are different and possibly in conflict.

Partly prompted by competitive contracting strategy, and partly in an effort to portray a tendency to be accommodating, prospective fixed-price contractors often offer to comply with all the conditions set forth in contract specifications, even if the contractor suspects that the client’s specifications are flawed. The reinforcing element for this behavior is that the clients often regard such conformist behavior positively. Notwithstanding, if there are changes to the project scope during the life of the project, such changes would be grounds for renegotiating the contract, usually to a higher price.

It is not known how many contractors could have predicted the nature and extent of the scope changes of a contract but chose not to confront the client about the quality of the specifications. However, it is commonly accepted that contractors of fixed-price contracts tend to prosper when there are many change orders during the life of the contract.

Ideally, when a set of specifications is presented to the project manager or to a potential contractor, and if there are flaws or omissions in the statements of scope, specifications, or desired procedures, the contractor or project manager should ethically and logically respond in any or all of the ways listed in Figure 6-13. Such responses will serve the best interests of the client, while also serving the best long-term interests of the contractor.

Sometimes, however, there is a conflict between the contractor’s short-term and long-term interests. The recommended responses are to ask questions when there is ambiguity, to list assumptions when the specifications are incomplete, to take exception when an objective is unattainable, and to make suggestions when the specifications need improvements.

Figure 6-13

Response to Client’s Requirements

Traditionally, contractors’ responses are more in line with compliance rather than the seemingly confrontational responses outlined in Figure 6-13. In some cases, the clients reinforce the contractor’s passive behavior by rewarding those who exhibit non-feedback and by punishing those who provide feedback that is not entirely complimentary (see Figure 6-14).

BIDDING

A bid and an estimate are two entirely different things, although sometimes clients and contractors use these two terms interchangeably. An estimate is a detailed account of the cost of delivering a product based on specific information about the actual cost of materials and equipment, on the actual salary of personnel, and on a realistic characterization of the overhead structure of the contractor’s organization; in other words, an estimate will reflect the real cost of a project. Depending on the circumstances, an estimate may or may not include overhead costs, indirect costs, and profit.

By comparison, the bid or contract price may not necessarily include details of the various components of the cost estimate that have formed the basis for the bid. Even if the bid does include details of components such as direct costs, indirect costs, overhead, contingency, and return on investment, these figures might not be actual or realistic.

Figure 6-14

Consequences (Responding to Client Requirements)

The amounts included in a bid simply represent the amounts that the contractor is planning to charge for labor, materials and equipment, indirect costs, overhead costs, contingencies, and the all-important return on investment. These values usually are developed for the purposes of the bid. The transition from an estimate to a bid is a business decision that is based on the probability of desirable or undesirable unexpected events occurring and on the bidder’s motivation to acquire this contract.

Generally, the profit margin in a contract must be in concert with the number of bidders for the same job, primarily because the prospective contractors, in an effort to be the lowest bidder, will reduce the overall profit to its lowest possible margin. As Figure 6-15 shows, when there are a lot of bidders for the same job, the expected profit margin is very low; for jobs with very few bidders, the profit margin will increase accordingly (DeNeufville and Hani 1977; Gates 1978). The most desirable situation for a contractor, clearly, is one in which there are very few bidders for the contract.

A low profit margin will increase the chances of being the successful bidder, although bidding a job below realistic cost does not necessarily guarantee wining the contract. On the other hand, an extraordinarily high profit margin might reduce the chances of being the successful bidder, although bidding a job with high profit margin does not necessarily eliminate all chances of wining the contract.

The presence of a contract creates an environment of delineated objectives that sometimes precludes a common focus on the project by the client and the contractor. Various efforts in the areas of partnering have established a less adversarial contract environment, but keep in mind that contractors and clients have different sets of motivations and objectives.

Figure 6-15

Effect of Competition on Bids

In a contracting situation, the bidder’s objectives are to win the contract, complete the project quickly, receive prompt payment, and make a good profit. On the other hand, the owner’s objectives are to pay the lowest price possible for the earliest delivery date and to receive a responsive performance. The number of lawsuits that clients and contractors file against one another demonstrates this adversarial attitude, which stems from the disparity between the client’s business objectives and the contractor’s operating objectives.

PROJECT COSTS

Normally when an internal project is commissioned, the cost of the project does not include anything beyond the cost of assigning personnel and equipment—sometimes not even the cost of equipment. However, the real cost of the project includes other cost components such as labor, equipment, materials, indirect costs, overhead, and return on investment.

The distinctions among direct cost, indirect cost, and overhead tend to be more important in organizations that conduct external projects. A sensitivity to the issues of indirect and overhead costs will allow an internal project manager to assess the real cost of an internal project and to compare two internal projects on the basis of direct costs. When comparing an external project with an internal project, care should be taken to include the necessary additional direct cost items of the internal project.

Direct Costs

Direct costs are those costs that are directly attributable to the project, such as personnel salaries, travel, and cost of buying or renting equipment for the explicit use of the project. One popular way of testing the direct cost elements is to consider the costs of those people and equipment that actually came in contact with the project deliverable, and for what duration. It is important to remember that if personnel or equipment are shared between projects, only the portion of the salary and purchase costs that were used for the activities of a particular project should be included.

Indirect Costs

Indirect costs include the costs of infrastructure and human and physical resources necessary for the project to operate smoothly, again to the extent that the resources were indirectly associated with the project. Indirect costs include the cost of items such as sick leave, vacation, training, Social Security contributions, health care, and retirement benefits for employees. Indirect costs also will include portions of the salary of supervisory personnel who support the project. Other indirect items are portions of the cost of administrative support, the phone system, faxes, computers, rent, insurance, taxes, and utilities.

Direct costs and indirect costs are items that can easily be related to the cost of implementing components of the deliverables. They are an integral part of the cost estimate of an external project and therefore should not be allowed to become subject to negotiations or alterations during the contract award phases.

Overhead

Overhead items are somewhat removed from the project, although they are necessary to conduct it successfully. They include compensation for the organization’s senior management and the cost of the infrastructure necessary to support their activities. Overhead items also include the cost of preparing unsuccessful proposals, general marketing and public relations, research and development for capability improvement, and ongoing innovative business ventures of the organization.

The extent to which these overhead costs should be charged to a project is always the subject of extensive debate between clients and contractors. This loosely knit bundle of cost categories is always under scrutiny by the prospective client, and therefore it is an issue of negotiation at the time of the award for a contract for an external project. Finally, a project is very unattractive if it does not produce a profit or return on investment.

The extent of return on investment is another issue of contract negotiation. The return on investment should provide a very strong motivation to the contractor for undertaking the project, unless the contractor is so desperate that he or she is willing to settle just for cash flow, or even for a slight loss.

Allowance

An allowance is a lump-sum estimate that is assigned to certain project items. It is somewhat akin to an analogous estimate for that particular component of the project. Usually, the basis for using an allowance for an item instead of a detailed estimate is that although the project manager predicts that a certain cost will be incurred, he or she also has determined that the elements cannot be identified with any accuracy or that a detailed tabulation is not necessary because the item is very small in comparison with other WBS elements.

An example of an allowance is the estimate for travel expenses. If the project manager knows that it is likely that the team might have to travel to the installation sites about a dozen times, he or she includes an allowance of $75,000 for travel expenses rather than estimating the cost of airline tickets and hotel costs for each separate trip. Other examples include the cost of office supplies, phone calls, and software licenses. An allowance should be used very infrequently, and even then only for those cost elements that comprise a very small percentage of the project’s overall cost.

Contingency

The terms “contingency” and “client reserve” often are used interchangeably, but they refer to two different kinds of buffer funds. In some ways, contingency funds and reserve funds are akin to allowances, except that contingency funds and reserve funds deal with unknown issues and issues outside the contract price structure. Sometimes, clients establish contingency and reserve funds even for internal projects, to put some formality in budget development.

For the purposes of this book, the term “contingency” is used for the funds that are added to the estimate to compensate for inaccuracies caused by uncertainties in project details. The term “client reserve” refers to those funds that are set aside to subsidize the cost changes brought on by expansions of client objectives, environmental changes, and sometimes client-directed design changes. Client reserve funds refer to those funds that are set aside by the client as part of the organizational budget, but apart from the contract budget.

The definition and purpose of contingency and reserve funds will become blurred if there are regular, or occasional, changes to the project scope during the life of the contract. The definition becomes even more blurred if the risk-related contingency funds are rolled together with client reserve funds in the same account. Contingency funds are not to be used to cover the cost of errors in design, implementation, or omission, or those caused by miscalculation in estimating. These items should be addressed as part of a renegotiation for or amendments of a new budget or contract.

Traditionally, the magnitude of contingency funds is from 10 percent to 50 percent of total project funds, depending on the volume of information available at the time of the estimate. This range is deemed appropriate because it is generally anticipated that when a project is advertised for bid, the objectives and statements of specification possess a reasonable accuracy of about 20 percent.

The magnitude of client reserve funds varies from 10 percent to 50 percent of the total project funds, depending on the level of innovation required in the project, which in turn might trigger major design changes (Anonymous1 2000; Anonymous21999; Anonymous5 1999; Vigder and Kark 1994). The level of client reserves also depends on the extent to which the client team, who developed the estimate, was familiar with cutting-edge developments in the area.

PROJECT AUDIT

If the organization hosting the project is highly sophisticated, it will conduct regular project reviews, and most of the stakeholders and all of the team members will be aware of the real status of the project. The regular project reviews might be performed by a central unit, such as a project management office (PMO).

Formalized audits will be unnecessary for projects or organizations that practice regular and detailed project monitoring, thereby giving a clear picture of the status of projects at all times. However, less enlightened organizations are not always aware of the status of all projects at all times. Therefore, occasional or regular formal project audits may be necessary to assess the real status of the project.

The usefulness of the project deliverables and the progress of the project’s implementation often are evaluated using a formal project audit. A project audit is different from a financial audit in that it concentrates on all project attributes, a small portion of which include the cost performance attributes.

The project progress attributes to be audited should include those that measure the pace of progress in terms of achieving the intermediate milestones, the cost of delivered items, and the quality or performance of the deliverables as compared with the most recent baseline. The audit also may take into account the behavior of contractor personnel, such as responsiveness and attitude. Ideally, the audit procedures for an outsourced project will focus on the same indicators that are normally monitored during the progress-monitoring phase of an internal project.

If the result of the audit shows that the project cost and schedule are out of control, and therefore completing the project will be far more costly or much later than anticipated, then the project might need to be terminated (see Figure 6-16). If the results of an audit, viewed in light of the current organizational strategic direction, deem an internal project no longer necessary or viable, that project can be terminated with reasonable ease. The personnel and equipment that were assigned to this internal project can then be dispersed through the organization somewhat systematically (see Figure 6-17).

Figure 6-16

Project Termination Types

Unless the external project is being terminated due to the poor performance of the contractor in any of the triple-constraint areas, and therefore in breach of the contract, terminating an external project is far more complex and costly than terminating an internal project. If the contractor is progressing in a reasonably satisfactory pace at the time the external project is terminated, then the client will negotiate to compensate the contractor for the cost of completed work, work in progress, mobilization for future tasks, early demobilization costs, and anticipated profits.

Figure 6-17

Scheduled Termination