3 Resource Breakdown Structure

Managers have a long history of dividing anticipated project work into smaller and smaller parcels and graphically presenting the resulting structure. As with the WBS, this “breaking down” of the work facilitates management of the project’s constituent elements in many ways. Similarly, during the very early stages of the project planning process, the project’s in-house resources should be examined in an equally methodical manner in the process of creating the resource breakdown structure (RBS). If internal resources need to be augmented, this RBS must include project-specific resources that the manager needs to obtain from outside the organization. The RBS will greatly facilitate the resource assignments and scheduling in this project and in similar projects that use these resources.

An RBS differs from other human resource or budgeting classification methods because it applies directly to project management and not necessarily to, for example, cost accounting or personnel evaluations. The practice of formalizing the resource pool falls at point of the overlap between general management and project management.

An RBS classifies and catalogs the resources needed to accomplish project objectives. In many ways, the RBS is analogous to the WBS and claims similar advantages in improving communication, integration, planning, and estimating. As the WBS does for the deliverable elements of a project, the RBS provides a consistent framework for dividing the resources into small units for planning, estimating, and managing.

Figure 3-1 shows a schematic representation of the familiar WBS. The project deliverable, at the top, has been broken into many smaller deliverables. Figure 3-2 is the schematic representation of the RBS for the same project.

Rather than developing a new RBS for each project, the organization might choose to develop various RBS for families of projects. In some cases, the project manager might modify and use the resource structure that was previously prepared by those charged with accounting for the overall organizational resources. As project managers plan each new project, they might select only those portions of the common RBS that apply to the project.

In the few organizations that currently use variations of an enterprise RBS, the project manager can capitalize on organizational memory and use this structure to determine an accurate estimate for the cost of the resources needed for the project. Thus, project managers can plan the project with greater assurance of the reliability of the resource data. Regardless of how extensively it is used, the project or enterprise RBS must be kept current and accurate as far as content and costs of individual resources.

Figure 3-1

Work Breakdown Structure

Figure 3-2

Resource Breakdown Structure

If the initial resource estimate of the project is prepared with reasonable accuracy, the proportional cost of each of the components of the project deliverable can be understood easily, even during the early stages of the project, when the structure and values may not be exceptionally accurate. The project estimate will be easy to review and improve as more information becomes available. As the almost inevitable changes of scope occur, further modifications to the estimate can be made formally, easily, and clearly.

Equally important, every change to the project cost can be justified and defended with detailed data. The incidence of scope creep can be significantly reduced, or even eliminated, when a detailed bottom-up estimate is prepared using a deliverable-oriented WBS and an appropriate RBS.

RBS DEVELOPMENT

An enterprise-oriented, or even a project-oriented, RBS is not used to plan any particular project. Instead, it tabulates the resources available to, or needed in, certain type of projects, or even for a specific project. Developing the RBS starts with dividing the pool of resources into entities specific enough so that this structure can be used as a catalog for resources that are necessary to deliver the project WBS elements.

Developing an RBS involves grouping all resources into approximately three to nine categories in Level One. Then, each of the Level One items is subdivided as described for the WBS in Chapter 2. Consistency in the division bases remains a crucial component of the structure. Ideally, the rationale for dividing one level from the next should be consistent across all elements and branches of the RBS, but at a minimum the division basis at any juncture must be the same for all children of the same parent.

The process continues until discrete, manageable resource items have been identified. A useful guide here is to keep dividing the resource pool until the lowest-level items reflect the level of resource detail that is of interest to the estimators and schedulers, stopping short of naming individuals. The RBS can be presented graphically, in a tabular fashion or using indented text.

Again, the level of detail at the lowest level of the RBS varies among companies and project managers. The nature of the resource pool and its administrative environment determine the depths of the levels. Notwithstanding, reasonable consistency must be maintained in the degree of detail of the lowest-level elements from all of the branches. For example, in a listing of materials for a construction project, if two resource branches end with nails and motors, respectively, there is not a consistency in significance of the individual resources.

Some high-priority projects may have limitless resources, for example, as many CAD operators, contract officers, or safety engineers as the project needs. On the other hand, if some of the resources are limited, the RBS may identify those resources. For example, it would mention that 14 civil engineers are available for a new project—or 2 cranes, 35 brick layers, 4 programmers, 3 photographers, and so forth.

Sometimes complications arise when the client provides some combination of equipment, funding, and personnel. Although in such cases the detailed solution varies depending on the nature of the project and the priorities of the organizations involved, the most logical and thorough approach would be to list all of the necessary project resources in the RBS—and in the estimate—regardless of how they will be funded. Once the total project cost estimate is prepared, the client-furnished equipment and labor costs can be subtracted from the resources requested by the project manager or the contractor.

Several examples of RBS are presented at the end of this chapter.

THE PRIMARY DIVISION BASES

The best, although not necessarily the only, lines of demarcation among the elements at the first level of the RBS are:

• People (labor)

• Materials and installed equipment

• Fees, licenses.

The labor category is sometimes referred to as people resources. Depending on organizational and personal preferences, people are grouped by skill categories, professional disciplines, and work functions, in addition to being grouped by location, account, and organization. The RBS should list all possible human resources, regardless of their physical location, administrative attachment, or contractual circumstances. Doing so will facilitate implementation of plans that might involve assigning personnel or allocating funds from different organizational entities.

Figure 3-3 shows the categorization of human resources along organizational lines. Figure 3-4 shows the RBS for the stack monitor project described in the WBS chapter.

Figure 3-3

Sample RBS

Figure 3-4

RBS for Stack Project

Tools and machinery are those physical items the project team members need to perform their duties successfully. Thus, when the project ends, the project team will remove the tools and machinery from the project environment. Examples of items in this category are testing hardware, hand tools, hardware to install project deliverables, and computers to monitor and evaluate the installation process. These items are usually leased or rented. Sometimes, purchasing this type of resource can be more cost-effective for lengthy projects, even though ultimately these resources still will be removed from the project site upon successful completion of the project.

For planning and cost estimating purposes, sometimes the leasing agencies roll the wages of the operator into the rental fee of the equipment. Consequently, when tools and machinery are rented or leased, some organizations treat the operator as an integral part of the physical equipment. This practice blurs the line between the human and physical resources and should therefore be used sparingly and only when it clearly makes sense to do it that way.

Installed materials and equipment are purchased for the project and ultimately are integrated and embedded into the project deliverable. Examples include fiberoptic cables, furniture, tape drives, monitoring equipment, pumps, ducts, and computers. Computers are one of several categories of items that might be listed under tools and estimated with a time-based unit, because some of them will be used by the project team during project implementation. Yet they also might be listed under embedded equipment and estimated as each unit because some of them will be embedded in the deliverable.

Fees and licenses refer to those cost items that do not involve any implementation or installation but are required to execute the project. Examples include insurance policies, bond agreements, permit fees, legal fees, license charges, and taxes. Fees can be divided by type or by cost.

Ideally, the project manager should plan, estimate, and manage all tasks and their respective resources independent of where the resources reside, administratively or physically. If a human resource is from an outside organization and the project manager intends to hire that person for an individual task, then that task and its associated resources should not be regarded as part of the project at hand. If the project manager does not have managerial authority over a certain resource, then this project manager has no major influence in the use of the resource. In these cases, the resource and the resulting product are aptly named “outsourced.”

Equipment, supplies, tools, and material can be categorized by size, function, cost, or technical area. Aside from these general guidelines, equipment, materials, and fees are highly dependent on the discipline of the project and must be dealt with on a project-by-project basis. However, categorizing people is common to all projects, and people are the most important resource in any project. Generally 40–50 percent of the cost of construction and industrial projects is attributable to labor costs. The cost of human resources is approximately 60–90 percent of the cost of systems and software development projects (Anonymous2 1999; Anonymous5 1999; Vidger & Kark 1994).

LOWER-LEVEL DIVISION BASES FOR PEOPLE RESOURCES

The level of detail with which an RBS defines a human resource depends on the organization, the project, and to some extent the individual project manager. That stated, the transition from one people-resource RBS level to the next should occur based on one of the following:

• Administrative unit

• Charge code of account

• Physical location

• Credential (in a particular discipline)

• Work function

• Skill level.

Organizational managers sometimes divide resources on the basis of their administrative affiliations, such as Company A, Contractor X, or Organization D. In other cases, they might prefer to catalog the resources into groups based on physical location, especially as it relates to proximity to the project site (e.g., people resources from Los Angeles, Boston, southern plants, or western contractors). Normally, the first three bases are more appropriate for higher levels of the RBS, while credential, function, title, and skill are more appropriate bases for lower levels.

The credential-discipline basis is used when resources need to be identified by their degree specializations, certifications, or other recognized credentials. A work function basis is used when managers must know workers’ functions, independent of their credentials. Position title basis is required when, independent of their credentials or job functions, people’s places in the organizational hierarchy determine their duties in the project. Examples of such divisions are contract officers, program directors, department chiefs, and divisional VPs.

Occasionally it is appropriate to classify project personnel by their degree of effectiveness and skill (e.g., expert, skilled, semi-skilled). Naturally, the skill designation should always be used in conjunction with credential or function designations, and not title. Therefore, when credential and function designations are used, a next level of resource can be created. For example, if the lowest level of an RBS branch is, say, programmers, then the next level can be created by indicating the skill level of this resource (i.e., competent, skilled, and expert).

Again, for best results, one must maintain a reasonable level of consistency in grouping the resources. For example, whether labor items are categorized by degree, job title, or job function, the categorization should be consistent across all labor items at that level of the RBS. The RBS should not be extended to the named individuals in the organization because that will confuse the resource allocation for a project. This practice would be appropriate only in exceptionally rare organizations where the resource profile is absolutely fixed and there is no likelihood of changes, and therefore all project planning is conducted on a resource-constrained basis, and with named resources.

Figures 3-5 and 3-6 illustrate the WBS and RBS for a systems development project. These figures show the similarities and differences between these two structures. The structures are similar in the sense that they have a logical basis of breakdown from a broader viewpoint to the most detailed. They are complementary in that WBS is client-centric and the RBS is team-centric. The WBS shows the results of the project as the client will see them, whereas the RBS highlights the means by which the team will implement the project. To be more specific, the WBS will describe the deliverable, whereas the RBS will describe the resources to be used in crafting that specific deliverable.

NOMENCLATURE, DIMENSIONS, AND UNITS

The term “resource” refers to anything that will cost money to obtain and is necessary to complete the project (e.g., labor, equipment, licenses, taxes). Money is not a resource in this breakdown structure, but it is used as a common denomination of all resources. Money represents the primary means by which resources are provided.

For example, consider that for internal projects, money is often not the exchange medium. Although resources such as worker hours or equipment may then be granted directly, the project manager should still regard them as resources to be listed in the RBS—resources whose cost will be absorbed by the enterprise, implicitly or explicitly. Even for external projects, money should not be treated as a resource; it is the means by which the client buys the project deliverable, and in turn it is the means by which the contractor buys all of the resources needed to complete the project.

Figure 3-5

WBS Industrial System Development

Figure 3-6

RBS Software System Development

Because workers are paid for their effort, albeit differently in internal and external projects, they represent an expense to the enterprise, and their efforts add up to the project cost. Therefore, resource effort should be viewed as equivalent to cost. These issues must be kept in mind even in organizations in which the cost of the project is reported only for materials and equipment, and possibly service, that must be purchased from outside the organization.

The RBS explicitly contains both the unit of measurement for each resource (e.g., foot, pound, cubic yard, equipment hour, labor hour) and the cost of a single unit of the resource (e.g., $200 per programmer hour, $10,000 per equipment hour). Discrete items that, individually or in groups, get consumed or used entirely in a project can be measured as “each,” for example, installed motors, doors, computers, and hard disks. The RBS may list either direct costs or total costs, i.e., overhead. However, all resource costs should be listed using identical or consistent measurement units, either with or without overhead, and not a blend of the two. Blending those resource costs that include overhead with those that do not completely destroys the accuracy and utility of the RBS, and ultimately that of the resulting project estimate.

The measurement unit for all time-related elements can be hours, days, months, or years, but the chosen unit should appear in all appropriate quantities (unless the numbers become unreasonably large or inordinately small). The same statement can be made about all other dimensions and combinations of dimensions involved in the project, such as length (inches, feet, yards, centimeters, meters, kilometers) or volume (gallons, cubic yards, cubic centimeters, cubic meters).

Consistency is particularly important for time-related items. If the same units of time are not used in all of the RBS elements, then the link between the RBS and the schedule always must include a conversion schema that develops one unit of duration measurement for all elements in the schedule. As a reminder of the importance of this consistency in the measurement units (and many other consistencies), consider the example of the Mars Climate Orbiter, which failed in September 1999 because one navigating group worked in English (FPS, foot-pound-second) units and the other in metric (SI, meter-kilogram-second) units (Kerr 1999). A much tighter consistency than this minimum requirement of working in the same unit system would be better.

The word “rate” means some quantity measured per unit of time (e.g., a worker’s cost rate could be measured in dollars per hour). If one needed to discuss the expense of a single item (e.g., a can of paint), the cost would be described not as a rate but simply as so many dollars per unit; the unit may be called “each.”

“Effort” is the product of workers and time, measured in worker hours, worker days, worker months, or worker years. At any given point in the project, the effort divided by the appropriate unit of time gives the number of workers. For example, if a project requires an effort of 100 worker years, completion over a year’s duration would require 100 workers; to be completed in six months (i.e., 0.5 years), 200 workers would be needed.

This illustration, however, ignores the effect of compression and expansion on the cost. It also ignores the effects of varying skill level, because we are assuming that all workers have a similar skill level and do similar work, which may not be correct. The number of resources that would be present during the execution of a given task, or the “instantaneous” worker need, will be called the “resource intensity” for the task. This intensity will become the input to the schemas by which resource loading histograms are prepared, which in turn would flag “overloading” of resources. The remedy for resource overload is either hiring more resources for that specific time frame or avoiding it by virtue of a schedule expansion, commonly referred to as “resource leveling.”

Units must be retained in such arithmetic, whether explicitly or implicitly, so that the translation from effort to cost occurs through the cost rate per worker (e.g., worker hours multiplied by dollars per hour per worker yields dollars). Figures 3-7 and 3-8 show a schematic representation of estimating the cost of using personnel or equipment over some duration. If three workers are used for four days, we have used 12 worker days (see Figure 3-7). Then, multiplying by the cost rate yields the cost for that effort. Calculating the cost of equipment is similar except that now the effort is measured in equipment days (see Figure 3-8).

“Estimates” are made through this conversion. Although the objective may be to estimate cost, the first, often hidden (and sometimes skipped) step is to estimate the effort. A conceptual estimate of an element can initially be the total cost, but ultimately detailed cost estimates must be based on estimates of the quantity of resources.

Figure 3-8

Equipment Cost

Resource Breakdown Structure Examples

Bank Data Conversion Software Project

Wireless Communications Project

Branch Network Restructuring Project

Industrial Construction Project

Home Building Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

Hardware Design Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

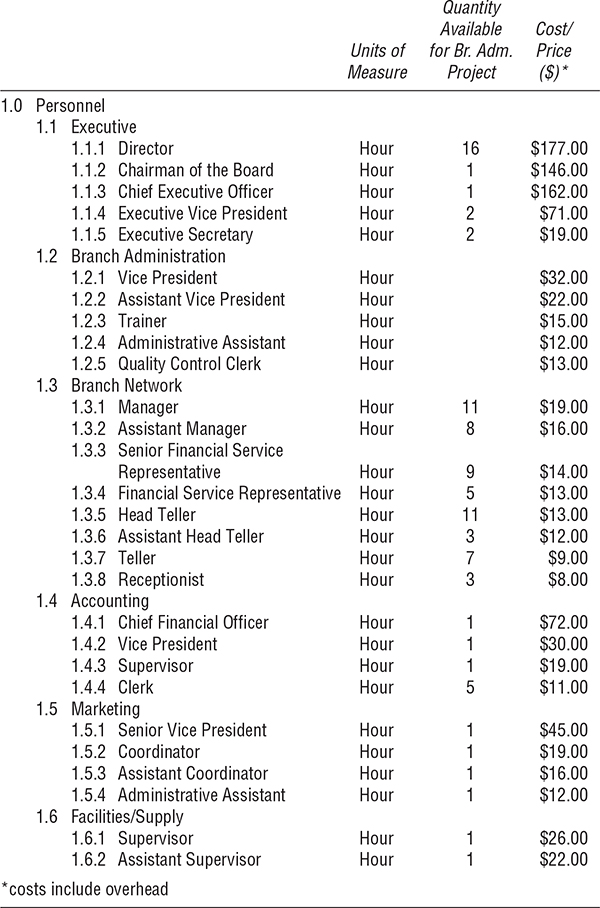

All personnel (Section 1.0) available in this project environment are salaried employees. A small amount of the fringe benefit may vary year to year, but for this assignment it is considered constant. Depending on the software utilized in creating the project schedule in later assignments, care must be given to make sure that an overtime rate is assigned as $0.00. The personnel resources are not able to receive overtime pay. In order to indicate this, all personnel rates are as given as cost/year. The personnel are first grouped by function. The lowest function level is then grouped by job title.

Most of the tools available in this project environment (Section 2.0, excluding section 2.5) are capitalized purchases. The tools are depreciated in a straight-line manner over five years. The depreciation value per year is included in the RBS for cost purposes. In order to allocate cost for the RBS it is assumed that the tools have been recently purchased; therefore, current book value is equal to purchase price. The tools are grouped by logical segments. Some segments are then further grouped by type.

The test boards and sockets (Section 2.5) are generated and charged on a per-project basis if needed. The boards are purchased from a vendor and processed as a sheet. The vendor can yield up to six boards but guarantees a yield of four. If the yield is higher than four, the charge does not change.

Health Services Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

The prices are derived from the websites of Salary.com, American Occupational Therapists’ Association, Occupational Therapist.com, the Washington Post, and Office Depot.

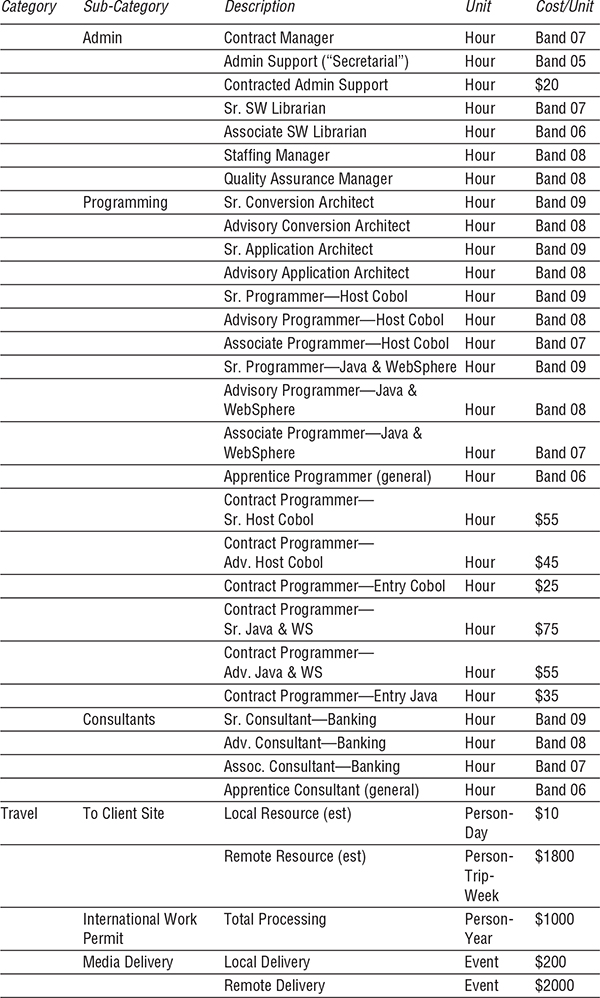

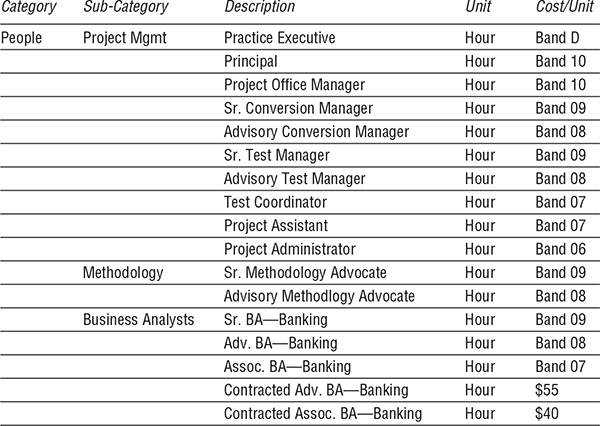

Bank Data Conversion Software Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

The following represents the pool of resources available for assignment to the project. Note that any project entry requirement costs (e.g., network infrastructure to support remote work) are assumed by the client to be external to the project and are not enumerated below.

All internal rates identified are valid for, and are guaranteed through, the calendar year 2003, and are valid for use of these resources in any geography in which the company operates. These rates are internally published and fully burdened and therefore already include many of the incidental ongoing expenses of the practice, such as home office support, cell phones, laptop computer, general software, office supplies, etc. Note that within a given discipline, the band level or title reflects the relative skill level of the individual in that discipline. The rates for each band level are identified in the final table.

Contractor rates, where used, are also fully burdened and apply to the same time period and geography, and are the rates negotiated with vendors approved by the purchasing organization.

As XYZ is so large, for all practical purposes, there is no limit to the availability of any of these skills.

Band Level Costs

Band Level |

Cost/Hour |

5 |

$60 |

6 |

$79 |

7 |

$91 |

8 |

$125 |

9 |

$165 |

10 |

$230 |

D |

$280 |

Wireless Communications Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

Branch Network Restructuring Project

Resource Breakdown Structure

Industrial Construction Project

Hierarchical Resource Breakdown Structure