Scripting languages are the software engineering equivalent of duct tape. Their powerful and expressive syntax makes them ideal for all of those extraneous ad hoc tasks associated with software development. Batch jobs, small utility tools, automated build processes, and throw-away prototypes are all suitable candidates for the use of a scripting language.

This chapter examines the benefits of using scripting languages on enterprise projects and introduces Jython, a Java implementation of the popular scripting language Python, which is tightly integrated with the Java platform.

A computer language is akin to a tool in the toolbox of any tradesman. Each tool is designed for a specific task, be it a hammer, a screwdriver, or wrench. Tools are an aid to productivity, but you only get the benefits of the tool by using it for the right task; hammers bang in nails and screwdrivers are for screws.

The same toolbox concept applies to software engineering. The choice of programming language for undertaking a specific task has a bearing on the developer’s productivity.

Java is obviously the main language on any J2EE project. Nevertheless, introducing concepts and language constructs from other programming paradigms can help when tackling areas of functionality to which Java is not ideally suited.

Java is a strongly and statically typed programming language. By contrast, scripting languages tend to be weakly typed and highly dynamic.

Strong typing is important for production systems, as the compiler scrupulously checks for any unintended type conversions, raising them as an error before the system is even run.

Mission-critical systems, such as military software and air-traffic-control systems tend to use Ada, a language developed by the Department of Defense that is considerably more stringent on type safety than Java. For these systems, the presence of an undetected defect could have lethal consequences.

Type safety is therefore a mechanism for assisting in the development of reliable and robust software, and it is an important language feature for any software that requires high levels of reliability.

However, not all software developed on an enterprise project falls into this category, and there are many extraneous tasks surrounding the development of the main application for which less scrupulous languages are better suited. This is where scripting languages enter the picture.

Here are some examples of these additional project tasks that can benefit from the use of a scripting language:

Exploratory prototyping of user interfaces

Writing code generators

Writing automated test scripts

Controlling batch jobs

Generating ad hoc reports

Automating build and release procedures

The next section considers the features of a language that make it well suited for scripting purposes.

Scripting languages lack the formal semantics of conventional languages like Java. They are loosely typed and highly dynamic, two features which make them ideal for noncritical project tasks.

The main features of a scripting language include

High level and informal language constructs

Expressive syntax

Loose typing

Interpreted as opposed to compiled

Over the years, the software industry has spawned a large number of languages that exhibit these features, a testimony to the benefits of scripting languages. There are many well-known and highly regarded examples:

Python

Perl

Ruby

Tcl

The biggest question facing a J2EE project team is which language to choose. The following lists some points to consider when making the choice. Does the language

Complement the experience of the project team?

Offer crossplatform support?

Integrate with Java, allowing access to existing Java classes?

In addition to these points, characteristics such as the language’s maturity, performance, and quality must also be considered.

With a number of languages to choose from, looking to assess the expertise of members of the team with a particular scripting language is an important consideration. Although offering powerful language constructs and informal semantics, scripting languages are not easy to learn. They employ many concepts that are not available in Java, meaning training time must be set aside to bring a developer up to speed.

tip

If the team is skilled in a language such as Python, then adopting Jython, the Java equivalent, is one way of leveraging that previous Python experience.

Investment in the education of a team in a particular scripting language should be part of a company’s wider adaptive foundation for rapid development. Standardization on a common scripting language across project teams allows the sharing of scripts and modules between groups. Staff will also be available in a mentoring role for projects using the scripting language for the first time.

Not all of the main scripting languages are crossplatform. Scripts can be migrated between machines with different operating systems and architectures only if an interpreter for the language exists for the target platform.

Java offers crossplatform support, and it would be preferable if a scripting language were available that offered the same capability. Language builders have addressed this problem by developing scripting languages that execute under a Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Thus, the language is supported on any platform that can host a JVM.

Several languages are available that fall into this category. Table 9-1 lists some of the open source offerings.

Table 9-1. Scripting Languages for the Java Platform

Description | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

Groovy | New language that combines many popular features from languages such as Smalltalk, Python, and Ruby | |

Jacl | Jacl (pronounced Jackal), or the Java Command Language, is a Java implementation of the Tcl scripting language | |

JRuby | Java implementation of the popular Ruby scripting language | |

Jython | Java version of the object-oriented scripting language Python | |

Rhino | A JavaScript interpreter written entirely in Java |

Several of the JVM scripting languages are implementations of popular scripting languages; for example, Jython brings Python to the Java platform, and JRuby is a Ruby implementation. Other languages, such as Groovy, have been created specifically for the Java platform.

For tasks such as writing ad hoc reports, producing automated test cases, or building user-interface prototypes, the scripting language must have the ability to work directly with Java objects.

This is the main reason for choosing a Java-based scripting language over one of the established languages. Without Java integration, many common scripting tasks are far more cumbersome, thereby negating the use of the scripting language.

To appreciate the relationship between scripting language and Java, the next section introduces Jython, a scripting language that is tightly integrated with the Java platform.

Jython is a pure Java implementation of the popular scripting language Python. Implemented entirely in Java, Jython runs under any compliant JVM. For its part, Python is a high-level, dynamic, object-oriented scripting language that has enjoyed considerable popularity with developers from all disciplines of software engineering.

The features of the Python language enable the writing of scripts that are far shorter than the equivalent code implemented in Java. The features of the Python language include the following:

Support for high-level data types, making it possible to express complex operations in a single statement

Loose typing, so variables do not have to be declared before they are used

A syntax that does not rely on curly braces or semicolons, instead using indentation to group statements and newline characters for delineating statements

This melding of the J2SE platform and Python has resulted in an exciting symbiosis. Jython harnesses the strength of the Python scripting language and offers crossplatform capabilities by virtue of the JVM under which it runs. Jython is also designed to integrate with Java, making it possible to access Java classes from within a script. Consequently, developers have the best of both worlds: access to the full services of the J2SE platform as well as the extensive set of libraries Python encompasses.

Jython’s features include the following:

Portability.

Jython code executes on any platform that supports a compliant JVM.

100% Java.

Anything you can do with Java, you can do with Jython. This includes the development of applets, GUIs, and J2EE components such as servlets. The only difference is that in Jython you’ll do it with fewer lines of code, albeit at the expense of type safety. You can also mix and match classes between the two languages. This includes being able to subclass classes defined in Java from Jython, and vice versa.

Interpreted and compiled.

As with most scripting languages, Jython code is interpreted. Although interpreting a language does incur a cost in terms of performance, the approach allows for changes to the code to be quickly applied and tested, thus avoiding the overhead of lengthy build cycles. Despite the decreased runtime performance, interpreting code offers better productivity gains over that of compilation. However, in this regard, Jython provides a bytecode compiler for converting certain Jython classes into .class files.

Embedded.

As well as being able to share classes with Java, Jython code can be embedded within Java programs. In this way, it is possible to have Jython code execute from within a Java application in much the same way as embedded SQL.

Object-oriented.

The Python language supports object-oriented language constructs such as classes and inheritance. The language is actually multiparadigm and provides procedural language semantics, including functions and global variables.

In the next sections, we cover the major points regarding Jython and the Jython scripting language:

Installing and running the Jython interpreter

The basics of the Jython language

Using a Java class from within a Jython module

Building a user interface using Swing components

Writing and deploying a servlet written as a Jython script

The first step is to download and install Jython.

Jython, along with a comprehensive set of documentation, is available for download from http://www.jython.org. The site details the installation steps and provides a few basic tutorials.

Note that Jython initially started out in life as JPython. The P has since been dropped in order to sidestep some tricky licensing issues. Jython is open source and available for free download and use. Nevertheless, as is the case with all software used within this book, you should carefully read the licensing terms before using any of the software covered.

documentation

The Jython site contains information that specifically relates to Jython, and not the Python language. For extensive documentation on the Python syntax, including a library reference and complete tutorial, visit the Python Web site at http://www.python.org.

There are several ways to execute Jython scripts. Starting the Jython interpreter in interactive mode allows Jython statements to be entered and executed directly from the Jython shell.

Launch the Jython interpreter using the appropriate command file found in the bin directory of the Jython installation. On a Windows platform, this is jython.bat.

Entering jython.bat at a command prompt starts Jython in interactive mode.

Jython 2.1 on java1.4.1_02 (JIT: null) Type "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. >>> x = 1 >>> if x: ... print 'Hello World' ... Hello World >>>

The interpreter accepts commands at the primary prompt, identified by the three greater-than signs: >>>. The secondary prompt accepts continuation commands and is identified by three dots: ....

Jython also executes Jython statements as scripts and exits the interpreter on completion. Jython script files typically have an extension of .py, and are submitted to the Jython interpreter for execution from the command line:

jython myscript.py

Now that we know how to run Jython programs and execute Jython statements, let’s examine the rudimentary elements of the Jython language.

To appreciate the brevity of the Jython syntax, we look at a complete example that demonstrates reading from a file. Manipulating files and file contents is a common use for scripting languages, so it is a good place to start. Here, the code opens a text file and displays the length of each word within the file.

f=open('sample.txt')

for word in f.read().split():

print word, len(word)

f.close()

The code shown isn’t a code snippet; it is a complete example. Firing up the Jython interpreter and entering the above statements gives the following output:

Monty 5 Python's 8 Flying 6 Circus 6

Notice that it isn’t necessary to define a class or even a main method. Furthermore, Jython’s type-less syntax means the example is devoid of any type declarations, keeping the code very succinct. Statements are also grouped by indentation and not by curly braces, as in Java, thereby keeping the script short and concise.

The file parsing example relies on Jython’s intrinsic support for compound data types such as lists and maps. The strip() function in the example transforms the contents of the file from a string to a list. The for statement then iterates over the elements of the list.

List processing is a powerful concept in Jython, making for a highly expressive syntax. Defining both lists and maps in Jython is very easy. Note Jython uses the term dictionary for lists that hold key/value pairs.

list = ['The', 'Life', 'of', 'Brian']

map = {10: 'The', 20:'Meaning', 30:'of', 40:'Life'}

The same declarations in Java are slightly more verbose:

List list = new LinkedList();

list.add("The");

list.add("Life");

list.add("of");

list.add("Brian");

Map map = new HashMap();

map.put(new Integer(10), "The");

map.put(new Integer(20), "Meaning");

map.put(new Integer(30), "of");

map.put(new Integer(40), "Life");

Jython wouldn’t be object-oriented without the ability to define classes. Here is a class declaration of type Customer, with methods update() and total().

# Customer class declaration

#

class Customer:

def update(self, value):

self.amount = value

def total(self):

return self.amount

The def keyword defines a function or method. The self parameter is important because it represents the equivalent of the this reference in Java. Jython implicitly passes this reference each time a method on an instance of the object is called.

note

Jython is not tied to the object-oriented paradigm, and unlike Java, allows the declaration of functions outside of the scope of a class.

Instantiating the Customer class uses another terse piece of syntax. Here is how to create an object and invoke its methods:

obj = Customer() # Create Customer instance obj.update(10) print obj.total()

The first line creates an instance of the Customer class. Note that there is no requirement in Jython to use Java’s equivalent of the new keyword or to define the type of the object being referenced by the obj variable. Jython only discovers whether the update() and total() methods actually exist on the obj reference when the interpreter attempts to execute those lines of code.

Now that you have been introduced to some of the basics of the Jython syntax, it’s time to move onto something more interesting. Up until this point, all the examples could have been completed using Python, the scripting language on which Jython is based.

The advantage of choosing Jython over Python, or over alternative scripting languages such as Perl or Ruby, is the ability of Jython to integrate seamlessly with existing Java classes.

To demonstrate this integration capability, we create a standard Java class and use it from a Jython script. Listing 9-1 shows the Person class.

Example 9-1. Person Java Class Declaration

public class Person {

private String name;

private int age;

/**

* Default constructor

*/

public void Person() {

}

/*

* Getter and setter methods for class properties

*/

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

public void setAge(int age) {

this.age = age;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

Before the Person class can be accessed from within a Jython script, you must set the CLASSPATH environment variable so Jython can find the new classes to load. Optionally, you may write an alternate Jython startup file that sets the classpath for the interpreter accordingly.

The following is a three-line script that creates and initializes an instance of the Person class and prints out its properties.

import Person obj = Person(name = 'Bill', age = 20) print obj.name, obj.age

The import statement pulls the Person module into the script’s namespace. If the classpath is set incorrectly, Jython will report an error at this point.

Once the class is loaded into the script, an instance of the class is created. The syntax used to initialize the object is a shorthand form. On loading the class, Jython scans the class for common patterns and can recognize JavaBean-compliant getters and setters. Jython represents these methods as properties and allows them to be set through the constructor using the notation

Person(name = 'Bill', age = 20)

With an instance of the Person class created, the final line prints out the two properties name and age. Again, note the convenience of being able to use property notation rather than formal method semantics.

Like Java, Jython supports inheritance, making it possible for classes to derive from both other Jython classes and Java classes. Jython supports inheritance through the syntax

Class DerivedClass(BaseClass1, BaseClass2, BaseClassN):

From the syntax, you can see that Jython goes beyond Java’s single inheritance and supports multiple inheritance. However, when Jython classes inherit from Java classes, only a single Java class can be included in the inheritance hierarchy of a Jython class.

Listing 9-2 shows a Jython script that has the Customer class extend the Person Java class. The integration between the two class types is seamless, with the main function accessing methods from both the superclass and the deriving Customer class.

Example 9-2. Script PersonDemo.py

# Import Person Java class

#

import Person

# Customer class declaration

#

class Customer(Person):

def update(self, value):

self.amount = value

def total(self):

return self.amount

# Main function

#

def main():

# Create instance of Customer

#

obj = Customer(name = 'Bill', age = 20)

# Using Customer properties

#

print obj.name, obj.age

# Using Person methods

#

obj.update(99);

print obj.total()

# Entry point for script

#

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Now that we have introduced Jython’s syntax and integration support for Java, the next sections provide examples of some uses for Jython scripts.

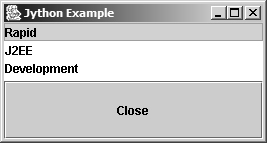

Scripting languages are ideal candidates for constructing exploratory prototypes of user interfaces. Using Jython’s integration capabilities with Java enables the development of user-interface prototypes with familiar Java class libraries, such as AWT and Swing. Listing 9-3 illustrates a simple user interface written in Jython and using Swing classes.

Example 9-3. User-Interface Script listbox.py

import java.lang as lang

import javax.swing as swing

import java.awt as awt

def exit(event):

lang.System.exit(0)

win = swing.JFrame("Jython Example", windowClosing=exit)

win.contentPane.layout = awt.GridLayout(2, 1)

win.contentPane.add(swing.JList(['Rapid','J2EE','Development']))

win.contentPane.add(swing.JButton('Close',actionPerformed=exit))

win.pack()

win.show()

The source file listbox.py can be executed directly from the command prompt by invoking jython listbox.py.

Figure 9-1 displays the output from the script.

Jython also makes a very good glue language. If server-side business components are already in place, Jython can serve as a rapid development language for building user interfaces that expose the underlying business services to the end users.

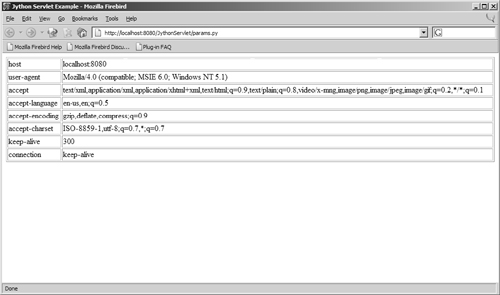

The Jython installation provides a special servlet that loads and executes Jython scripts within a Web server’s servlet engine. This handy utility allows servlets to be written and deployed as Jython scripts.

Servlets are ideal candidates for use in rapid prototyping. They are easily built and deployed, and can operate independently of the server’s EJB container. Using Java, however, servlets still need to be compiled, deployed, and configured. This is not so for the Jython servlet script; it only needs to be deployed.

Listing 9-4 provides an example of a servlet implemented in Jython.

Example 9-4. Jython Servlet Script params.py

# params.py

import java, javax, sys

class params(http.HttpServlet):

def doGet(self, request, response):

response.setContentType("text/html")

out = response.getWriter()

out.println("<HTML>")

out.println("<HEAD><TITLE>Jython Servlet Example</TITLE></HEAD>")

out.println("<BODY>")

out.println("<TABLE BORDER="1" WIDTH="100%">")

for name in request.headerNames:

out.println("<TR><TD>" + name + "</TD>");

out.println("<TD>" + request.getHeader(name) + "</TD></TR>")

out.println("</TABLE>")

out.println("</BODY></HTML>")

Running the servlet first requires configuring and deploying Jython’s PyServlet. This servlet is responsible for loading and executing Jython scripts on the fly. The servlet is configured in the Web application’s web.xml deployment descriptor, as shown in Listing 9-5.

Example 9-5. PyServlet Configuration in web.xml

<servlet>

<servlet-name>pyservlet</servlet-name>

<servlet-class>org.python.util.PyServlet</servlet-class>

</servlet>

<servlet-mapping>

<servlet-name>pyservlet</servlet-name>

<url-pattern>*.py</url-pattern>

</servlet-mapping>

You can test out the Jython servlet with a suitable servlet container such as Apache’s Tomcat. First, create a new directory structure for the servlet under the webapps directory: <TOMCAT_HOME>/webapps/<context>. If necessary, copy one of the example Web applications that come with the Tomcat installation.

Modify the web.xml deployment descriptor so it contains an entry for PyServlet, as shown in Listing 9-5. You also need to copy jython.jar to the lib directory of the Web application: <context>/WEB-INF/lib. The jython.jar is needed to load the Jython interpreter. Alternatively, the servlet parameter python.home can be set, which specifies the location of the jython.jar. If this parameter is not defined in the deployment descriptor, PyServlet assumes <context>/WEB-INF/lib by default.

The final step is to copy the Jython script, in this case, params.py, into the newly created <context> directory structure. Start Tomcat and test the servlet by accessing

http://<host_name>:8080/<context>/params.py

Figure 9-2 shows the output from the servlet.

Jython is not the only scripting language to provide such good support for Java. Another scripting language worthy of consideration is Groovy, a Java-centric scripting language that is rapidly growing in popularity.

Jython is a mature Java implementation of the well-established scripting language Python. Groovy is a relative newcomer to the scripting scene, but it is gaining such interest that it threatens to eclipse Jython as the Java developer’s preferred scripting language.

Like Jython, Groovy is 100% Java and offers the same seamless integration with the Java platform. Unlike Jython, Groovy is not a Java implementation of an existing scripting language but is designed from the ground up for use by Java developers, although it does borrow some of the best features from languages such as Python, Ruby, and Smalltalk.

Groovy’s creators, Bob McWhirter and James Strachan, intended the language to feel immediately familiar to Java developers and stayed with the curly braces. You can even use semicolons, but they are optional, presumably for those of us who can’t get out of the habit.

Functionality wise, there is little difference between Jython and Groovy, although Groovy may look a little slicker in the tools it provides. Groovy even has the equivalent of Jython’s servlet, known as a Groovlet.

What makes Groovy so interesting is its acceptance under the Java Community Process as JSR-241, The Groovy Programming Language. When finalized, this will make Groovy the second official language for the J2SE platform. This is an exciting prospect, as a second language confirms J2SE as a true development platform and more than just the Java language. In this regard, it is possible Groovy is blazing a trail for other languages to follow.

Groovy resides under the Codehaus at http://groovy.codehaus.org. The language is well advanced but as of this writing is available only as a beta. The latest Groovy installation is available from the site. The site also provides extensive documentation with plenty of examples.

If you are keen to try Groovy, you might like to implement the Jython examples shown in this chapter using the Groovy language as an exercise. This exercise will help you determine which of the two scripting languages best suits your needs. Choosing between the two might be a dilemma, but it’s nice to have such a good choice.

Jython offers the developer a powerful scripting language. Jython’s major strength is as a glue language working with existing Java classes. Thus, it is ideal for developing throwaway prototypes, either behavioral to show the customer or structural to validate part of the architecture. You’ll find it has a thousand and one uses, and you will find yourself applying it to tasks you’d never before contemplated with languages like Java.

If Jython isn’t for you, then there are plenty of alternatives to consider. Groovy is proving very popular, and Java implementations of high-profile scripting languages like Ruby and Tcl are also available.

Above all, do not be put off by the learning curve of a dynamic, type-less scripting language. Once you master it, you’ll wonder how you ever got by without it.

New languages are being designed all the time. Admittedly, many have a lifespan similar to that of the fruit fly. Nevertheless, the good ones do tend to stick around. As developers, we should have an open mind about what new languages may offer. Who knows—the next template-based, object-oriented, pattern-centric, scripting language may have something to offer that makes all of our jobs a little easier.

For the next chapter, we move on to a different paradigm and examine how rule-based languages are well suited to expressing business logic in enterprise applications.

If you’d like to learn more about Jython, several books are available in addition to the online resources mentioned in this chapter. Jython Essentials [Pedroni, 2002] by Samuele Pedroni and Noel Rappin is an informative text, as is Jython for Java Programmers [Bill, 2001] by Robert W. Bill.

To keep track of the progress of the Groovy JSR, see the Java Community Process site at http://jcp.org/en/jsr/detail?id=241.