Introduction

Challenges for entrepreneurship education

Karin Berglund and Karen Verduijn

Introduction

The last decade or so has witnessed the rise of “critical” entrepreneurship studies (CES). CES questions dominant images and conceptualizations of entrepreneurship, entrepreneuring and the entrepreneur, and create room for other understandings and approaches. Generally, critical entrepreneurship scholars feel a need to connect entrepreneurship (more) to society (and not only to the economy), and to make students aware of this.

In this book we build on the presumption that it is timely to interrogate if and how CES contributions and insights have entered our classrooms. With students interested in the entrepreneurship phenomenon generally expecting merely the “conventional” (instrumental) approach towards the same, and for us to stipulate the importance of new venture creation with regard to our economy’s health and vitality, some of us (i.e. entrepreneurship educators) might see the need to point at how entrepreneurship is broader than that, that there are multiple “versions” of it, that the entrepreneurial identity is a layered one, and not without its repercussions, and that entrepreneurship provides us with a Western world discourse that is classed, gendered, ethnocentric and thus excluding. Yet many new versions wish to tackle such issues, while paying attention to troublesome global developments, where contemporary neo-liberal displacements become entwined with entrepreneurship and blur boundaries between individuals, organizations and society. By shifting responsibility from society to the individual, thus bringing entrepreneurship in in new guises, it is no longer (solely) a question of economic and other gains but of taking (social, ecological and cultural) responsibility. However, when neo-liberal pursuits attempt to open up market society, the economic dimension is not pushed aside but spills over into and influences all the other aspects of life today. This provides a challenge and poses questions as to how to enact this in our classrooms and thus offer a critical entrepreneurship education.

We situate critical entrepreneurship education at the crossroads of “lower education” (preschool, compulsory school, upper secondary school) and higher education. While lower education has witnessed a striving to broaden the understanding of entrepreneurship by, for example, linking it to social and environmental issues, creativity and also democracy and politics (cf. Leffler, 2009; Holmgren, 2012), this broader view is rarely reported on in literature on entrepreneurship pedagogy used in higher education (for an exception see e.g. Hjorth, 2011; Barinaga, 2016). At the same time, in preparing this volume, we have come across many initiatives positing entrepreneurship as a broader phenomenon, and problematizing its different faces in our teaching. In experimenting with pedagogical purposes, approaches and content, the authors in this volume work with such issues as reflexivity, gender, the entrepreneurial self, responsibility, awareness, creativity and vulnerability. To further spur this kind of development, this book aims to make it clear why critical questions need to formulated, and how they can be enacted to evoke students’ understandings of the plurality of entrepreneuring (cf. Chapter 4 in this volume). Evoking students (and ourselves) to new entrepreneurial realities aligns well with a need to also challenge ourselves and our students to engage in a dialogue of what entrepreneurship (education) might become.

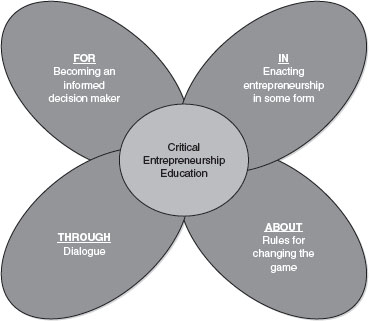

In this introduction we provide the reader with a short reminder of how entrepreneurship education is generally categorized in teaching “in”, “for”, “through” and “about” entrepreneurship. We also discuss some of the contemporary concerns of the field of entrepreneurship education. This is followed by an introduction to critical entrepreneurship studies and the questions that guide such efforts. Third, we discuss concerns expressed in critical pedagogy literature, especially in relation to the enterprising self, as well as some of those offered by the critical management education literature. Fourth, we sketch what this may entail for (critical) entrepreneurship education. We conclude by introducing the individual chapters in the book.

The field of entrepreneurship education

Entrepreneurship education (EE) has gained increasing attention and no longer interests only scholars in higher education but also teachers in elementary school, along with politicians, policymakers and education stakeholders. In a literature review, Alain Fayolle (2013) concludes that the field of EE is fragmented. There is little consensus on what unites EE, how the field (or area) should be defined, and what it contains in terms of theories, issues and teaching philosophy and pedagogies (also see Nabi, Linan, Fayolle, Krueger & Walmsley, 2017). Rather, at best diversity, and at worst fragmentation, seem to prevail. This may be an effect of the expansion of EE to broaden its focus and encompass more in terms of its objectives (O’Connor, 2013) and pedagogies (Nabi et al., 2017). Kirby (2007) points to the need for entrepreneurship educators to “develop graduates who can be innovative and take responsibility for their own destinies not just in a business or even a market economy context” (p. 21). Thus, EE has transgressed from being limited to offering a place for students to learn about the creation of new ventures to inhabiting a space where it sets out to facilitate for (young) people to be able to “cope with uncertainty and ambiguity, make sense out of chaos, initiate, build and achieve, in the process not just coping with change but anticipating and initiating it” (Kirby, 2007, p. 23). It appears that EE is used for many different things, in different contexts, with different groups and for different reasons.

A division of EE into the categories “about”, “for” and “in” was made by Jamieson in 1984. This division has spurred scholars to develop ideas relating to the diversity of and within entrepreneurship education. With reference to Henry, Hill and Leitch (2003), Taatila (2010) defines “for” as a preparation for self-employment/venture creation, and “in” as a form of management training for established entrepreneurs. To Kirby (2007), “for” is about developing the attributes of entrepreneurship in students, “through” is when the business startup process is used to enable students to acquire both business understandings and entrepreneurial competences, and “about” refers to the traditional pedagogical process of teaching students by providing them with academic knowledge about entrepreneurship. We adopt these four angles (in, for, through, about: IFTA) to shed some light on the diversity with regard to how entrepreneurship is thought of, shaped and practised in an educational context.

Within the scope of our introduction to entrepreneurship education, we want to highlight a few concerns voiced by entrepreneurship educators. First and foremost, there is a growing awareness that entrepreneurship is more than “business making” (cf. Gibb, 2002; Kirby, 2007; Thrane, Blenker, Korsgaard & Neergaard, 2016). With entrepreneurship education initially focusing on new business creation, and doing so by adopting predominantly economic and business perspectives and models, we see a wider range of approaches being embraced, and a growing number of entrepreneurship courses and programmes adopting a “broader” definition of entrepreneurship (i.e. as more than business making). With this broadening of previously set boundaries, we also witness a call to continue to wonder how entrepreneurship education can remain (or be made) entrepreneurial (cf. Kuratko, 2005; Fayolle, 2013; Hjorth & Johannisson, 2007). Experimenting with both ways to bring the various understandings of entrepreneurship to the fore and in particular “where” to teach our courses seems to be a relevant theme. In experimenting with pedagogical approaches, emphasis is being placed on the creative-relational nature of learning (cf. Hjorth & Johannisson, 2007; Hjorth, 2011), with reflections on not only our roles as educators and our (hierarchical) positions in teaching but also the relationality involved in engaging students as active (co)learners. In thinking about our roles as educators, we may feel the need to explore the relationship between education and provocation (Hjorth, 2011), with less emphasis on “reproductive continuity” (i.e. the reproduction of knowledge) but with more room for invention, i.e. creating other concepts, allowing for new ways of understanding (ibid.).

Notwithstanding these developments and the variety of and in (designing) entrepreneurship education, there appears to be a striking consistency with regard to an assumed consensual aim for more and more students to start up a business (or, broadly, organization) either after or during the education. The idea of promoting entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education is both omnipresent and pervasive (also see Nabi et al., 2017), to the extent that students are not only educated for entrepreneurship but also graduated to do it. Pittaway and Cope (2007) write that there are “two distinct forms of output: first, to enhance graduate employability and second, to encourage graduate enterprise” (p. 485). When the assumption is “the more, the merrier”, the ambition to broaden entrepreneurship education may falter as it is locked into its own narrow box where performativity rules (cf. Dey & Steyaert, 2007). The knowledge that counts is the knowledge that can be acted upon and measured in terms of success or failure, whereby learning for the sake of learning is by definition ruled out. It is this tendency to shift the “why” of education, or at least make it more one-sided, that is of concern to critical thinkers (Ball & Olmedo, 2013; Dahlstedt & Fejes, 2017). Entrepreneurship is transformed into a guiding principle for how we are to conduct our lives in accordance with the formula for “entrepreneurial freedom”. This may involve starting a new business of the conventional type and taking a product to the market, or becoming self-employed and “living your dream”: at best a “free life”, at worst a life where you struggle to make ends meet, something you share with many others in a similar precarious situation. Or it could imply having to continuously ask yourself how to improve as if you were your own producer, marketer and seller (Berglund, 2013). Or it may involve engaging with others to come to grips with such societal concerns as inequality, social exclusion or environmental pollution, with entrepreneurship becoming the process of joint efforts to turn this problem into an opportunity where the two logics of solving a problem and thriving on the market may turn into a conflict. Entrepreneurial logic intervenes and turns stable employment into a process of employability; it compels us to engage in our personal development rather than to enjoy it; it moves political and voluntary action into the background as ideas for our collective good are offered through entrepreneurial paths. Thus, entrepreneurship (and the education that follows) is not simply one course among others to choose from, but has paved the way for how we can live the present. It is exactly this tendency, and the omnipresence of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education, from which there is no escape, not as students, teachers, children, adults or simply humans. This is of concern when entrepreneurial values underpin the idea of the contemporary citizen (Dahlstedt & Fejes, 2017). If entrepreneurship education is to remain vital, we cannot deny these problematics since entrepreneurship (and entrepreneurship education) are everywhere. As entrepreneurship educators we must embrace these problematics, ponder over them, use “other” theories to reflect on them, continue to pose new questions and invite our students to do so as well. So, to keep EE “fresh” we should remind ourselves of the dangerous side of it, in particular that which has seemingly become “untouchable” from interrogation. We can therefore no longer avoid the provocative questions (cf. Hjorth, 2011) but should instead use them to ask ourselves, and our students, whether there are other ways to live the present than the “conventional” entrepreneurial way.

We will return to IFTA in the fourth section to shed light on what a critical reflection of entrepreneurship can bring about in proposing “other” forms of in/ for/through and about. But first we invite the reader to “enter” the field of critical entrepreneurship studies, for it is usually from the concerns raised in that field that educators start to think of raising critical awareness in relation to their entrepreneurship courses and/or programmes.

Concerns of critical entrepreneurship studies

This section offers an in-depth elaboration on critical entrepreneurship studies (CES), which builds on Denise Fletcher’s short introduction to the subject. Having already witnessed two reviews of this field (Spicer, 2012; Fletcher & Selden, 2015), we can say without hesitation that it has expanded considerably since the early days of Nodoushani and Nodoushani (1999), Ogbor (2000) and Armstrong (2005). In line with Alvesson and Willmott’s (1996) definition of critical management studies, critical entrepreneurship studies has set out “to challenge the legitimacy – and counter the development of – oppressive institutions and practices, seeking to highlight, nurture and promote the potential of human consciousness to reflect critically upon such practices” (p. 13), specifically in connection to entrepreneurship discourse (cf. Armstrong, 2005) and entrepreneurial practices (cf. Beaver & Jennings, 2005). Some milestones that we believe have shaped the field are the “movements books” by Daniel Hjorth and Chris Steyaert (2003, 2006, 2010), which together with special issues (Hjorth, Jones & Gartner, 2008; Tedmanson, Verduijn, Essers & Gartner, 2012; Rehn, Brännback, Carsrud & Lindahl, 2013; Verduijn, Dey, Tedmanson & Essers, 2014; Essers, Dey, Tedmanson & Verduijn, 2017) have challenged mainstream understandings and discourses of entrepreneurship.

CES offer insight into how entrepreneurial discourses have multiplied by expanding into new contexts (such as social entrepreneurship; see Ziegler, 2011), where entrepreneurship benefits values over and above economic values, where an understanding of entrepreneurship as socially constituted is shaped (Fletcher, 2006; Jack et al., 2008; Korsgaard, 2011) and where entrepreneurs “other” than the stereotypical Western world self-made middle-aged man are given a voice (Banerjee & Tedmanson, 2010; Achtenhagen & Welter, 2011; Essers & Tedmanson, 2014; Ozkazanc-Pan, 2014). Critical scholars continuously testify to how entrepreneurship continues to pervade many areas of not only economic life but also social life, including the world of school (Berglund, Lindgren & Packendorff, 2017). Altogether, this expansion of entrepreneurship discourses is aligned with solutions for coming to grips with the shortcomings of conventional entrepreneurship such as its economic roots and excluding tendencies. Despite efforts to alter entrepreneurial discourses, it is recognized that they are entangled with a capitalist ideology and surely do not offer “solutions” to its crises (Costa & Saraiva, 2012; Marsh & Thomas, 2017), but may rather work as “prophylactic action” (Vrasti, 2009).

All in all, CES adopt and span a wide variety of theoretical approaches and disciplines. These are not limited to theories of political economy as influenced by post-Marxism or the Frankfurt School type of critical theory but include postcolonial views (Essers & Benschop, 2009; Essers & Tedmanson, 2014), non-entitative, processual stances (Nayak & Chia, 2011; Hjorth, 2013; Verduijn, 2015) and feminist theoretical perspectives (Calas et al., 2009; Pettersson et al., 2017), as well as political-philosophical perspectives addressing the enterprising subject (du Gay, 2004; Hjorth & Steyaert, 2010; Jones & Spicer, 2005; Berglund & Skoglund, 2016).

This has resulted in a vein of CES contributions that are sceptical about entrepreneurship studies, some of whom issue a firm “warning”. Such contributions question dominant assumptions being attributed to the entrepreneurship phenomenon, its grand narratives and – more generally – the ideological distortions of mainstream entrepreneurship research (including its paradigmatic roots). Indeed, such contributions engage openly with the “dark sides” of and within entrepreneurship (such as the contradictions, ambiguities, tensions and paradoxes inherent in entrepreneurial activities; cf. Armstrong, 2005; Jones & Spicer, 2009; Costa & Saraiva, 2012; Olaison & Sorensen, 2014). Alongside this sceptical vein we witness a vein of contributions that form explicit hopeful attempts to “open up” our understanding of the entrepreneurship phenomenon to a more affirmative stance. Such contributions rearticulate entrepreneurship in the light of issues of societal production and emancipation (cf. Steyaert & Hjorth, 2006; Calas et al., 2009; Berglund Johannisson & Schwartz., 2012; Al-Dajani & Marlow, 2013). Together, these veins form the “double-edged sword” that constitutes CES (also see Verduijn et al., 2014), which needs to be reflected upon when critical entrepreneurship enters the classroom. Presenting entrepreneurship from a critical perspective simultaneously necessitates providing students with a space where it can be reconstructed. We will come back to how we can move from deconstructing entrepreneurship to reconstructing the same, but before doing so we will consult our “older” neighbours – critical management education and critical pedagogy – to see what lessons we can integrate in the emerging field of critical entrepreneurship education.

Learning from our neighbours: critical management education and critical pedagogy

Against the backdrop of the need to bring critical concerns to entrepreneurship education, we have turned to critical management education contributions as well as to critical pedagogy’s writings on entrepreneurship and literature on the enterprising self to see if we can “borrow” some lessons for critical entrepreneurship education from them. To be sure, the critical pedagogy focus is not aligned with mainstream entrepreneurship education’s concern of how to better train people in business making, or to become “entrepreneurs of the self”, and stimulate (more) students to do so. Our attempt is by no means an attempt to arrive at a comprehensive overview of either critical management education or critical pedagogy literature. As stated, it is, rather, an attempt to learn from others who have already struggled with similar concerns for a longer period of time and have experience in bringing these concerns into their classrooms.

The concerns expressed in critical management studies typically translate into critical management education by means of a set of principles in relation to curriculum development (Choo, 2007a):

• The curriculum is expected to embrace humanistic and liberal studies and subsume cultural, social and political cognitive perspectives.

• It should not encapsulate only performance-related financial values or interests that are trapped in what Weber (1978) (in Choo, 2007a) called “instrumental rationality”.

• The modalities of teaching and learning are expected to include an element of critical reflection to encourage students to question both hidden pedagogical assumptions and those that are taken for granted as received wisdom in both knowledge and practice.

• The critical reflection must provide students with opportunities to question what Argyris (1996) (in Choo, 2007a) called the “undiscussable”; that is, questioning coherent sets of values, beliefs and practices which are constructed and disseminated by lecturers to sustain their legitimate role as teacher, and the assumptions that are taken for granted and usually concealed during teaching.

• The methods of assessment are expected to be emancipatory, i.e. to support student empowerment and promote equal treatment and opportunity.

• The emancipatory process should also provide students with opportunities to identify and contest sources of inequality and treatment of minorities, and question the assumptions implicit in tutors’ assessment methods.

• The learning environment is expected to be democratic and participative and have a collective focus.

Many CME contributions mention the particular problematic found in the context in which management education typically takes place, namely the business school/MBA programme (cf. Currie, Knights & Starkey, 2010). With a fair number of contributions signalling this and other significant barriers to introducing critical management education (such as – more generally, and not only pertaining to the business school context – institutionalized assessment rules and regulations, marketization of higher education, learning styles and cultural diversity of students; see Choo, 2007b), we also see attempts at rethinking management education (Beyes & Michels, 2011), with an emphasis on opening up and connecting to the “problematics of society” (Beyes & Michels, 2011), and to how institutions of management education can enact “other spaces”, as productive forces.

In a similar vein, the ambition in critical pedagogy literature is to inform the reader about the power relations in play in the shaping of entrepreneurial students and teachers (Peters, 2001). The articles are descriptive (in contrast to normative) and take an analytical interest in how enterprise culture has come to govern education. Key concepts are not “idea”, “business”, “opportunity” and “discovery” but rather “governmentality”, “enterprising self”, “enterprising culture”, “subjectivity” and “power”. These are used by critical pedagogues and can be adopted to inform the student about critical issues that are part of the introduction of enterprise (and entrepreneurship) in schools. So let us start by introducing these analytical key concepts.

Neo-liberalism typically describes economic imperatives of enhancing privatization and de-regulating markets (Harvey, 2005). Critical pedagogy is not interested in the economic implications of this shift but in how an enterprise culture changes learners’ and educators’ relations to themselves as well as to others. Consequently, the pedagogical interventions developed, more broadly under the influence of enterprise culture, and more specifically within the framework of entrepreneurship education, are understood as a particular kind of governmentality which connects students and teachers to a capitalist logic and to the rationality of the market (e.g. Dahlstedt & Hertzberg, 2014). Governmentality refers to the productive power to govern through mentalité, e.g. “mind” (Foucault, 1978/1991). This mode of governing is not directed towards setting limits and boundaries but works through the individual by producing subjects, forming subjectivities and behaviour and enhancing the emergence of an organization of the social, which, assessed from an economic rationale, is seen to be more effective (Brown, 2003).

Neo-liberalism is inextricably linked to a need to foster enterprising selves. The enterprising self can, broadly, be described as a life form constituted by the autonomous, self-regulating, responsible and economically rational individual (Barry & Osborne, 1996). The enterprising self forms a subjectivity from which both the entrepreneur and the entrepreneurial student/teacher are given their contours. De Lauretis 1986 (in Ball, 2003, p. 227) defines subjectivity as “patterns by which experimental and emotional contexts, feelings, images and memories are organized to form one’s self image, one’s sense of self and others, and our possibilities of existence”. In neo-liberal societies the enterprising self is further promoted by turning education into a personal and ethical investment of the individual (Peters, 2001, p. 60). The enterprising self informs us of the need to be(come) an ambitious person who takes responsibility by giving her or his life a specific entrepreneurial form (cf. Lemke, 2001). Thus, the enterprising self can be understood as a “template” from which various kinds of entrepreneurial identities are configured. Analytically, it informs us of the myriad of entrepreneurial becomings that can be constructed by combining, say, “education + enterprise + responsibility + creativity + freedom + opportunity + future”. In this vein, entrepreneurship, as part of a broader culture of enterprise and neo-liberalism, will trickle down to schools, where enterprising selves can be fostered, shaped, affirmed and applauded (as we have described above).

The connection with a need for a more critical outlook on entrepreneurship education is easily made. Broadly, criticism is directed at what neo-liberal logic does to us, through an emphasis on entrepreneurship in policy (e.g. Connell, 2013; Dahlstedt & Tesfahuney, 2011) and curriculum (Dahlstedt & Hertzberg, 2014) and how it intervenes through enterprise culture (e.g. Peters, 2001; Down, 2009) and also through particular educational or training programmes (e.g. Bragg, 2007; Bendix Petersen & O’Flynn, 2007). The criticism expressed is that students and teachers alike are connected to the rationality of the market, with the activity and productivity of individuals being linked to global competitiveness and employability. With critical pedagogy insights, entrepreneurship in education not only signals the hopes for (more) new businesses and innovations, but also the seeking to prepare students for a society where they need to take responsibility to a greater extent than before. Bragg (2007), for example, has investigated how personal goals and aspirations are voiced in efforts to make students create opportunities for their futures and take responsibility for turning their ideas into action. This, as Bragg (2007) asserts, requires work on the self, involving both inspection of the self and self-criticism as these young people learn to strive for “endless potentiality” (cf. Costea, Amiridis & Crump, 2012). A similar story unfolds in Bendix Petersen and O’Flynn’s (2007) study of how an award scheme is taken up by students in a prestigious Australian private girls’ school. The award scheme is extra-institutional, but the school participates in organizing it with the aim of providing students with an opportunity to “accept a challenge” and “set a personal goal and achieve it”. Along the way, students learn about themselves and “about qualities like responsibility, trust and the ability to plan and organize themselves” (p. 202). Placing this award scheme in the analytical frame of how neo-liberal governmentality fosters a particular enterprising self, Bendix Petersen and O’Flynn (2007) show how this programme actually constitutes a powerful technology of the self as it invites young girls “to desire and assess worthwhileness along entrepreneurial lines: to gaze upon themselves as malleable, flexible, always-improvable portfolios and learn to assess themselves as successful or failing accordingly” (p. 209).

In addition, responsibility is rolled down not only from global and national institutions onto the individual, but also from adults to children. The citizen, in many Western democracies, is still entitled to particular rights, but she is increasingly being processed to ask herself what she can do for herself, for her community, her organization (cf. Scharff, 2016). And children are invited to think about what they will be able to do for themselves in the future (Berglund et al., 2017). If we made EE in higher education more critical, could we stimulate students to be creative in rethinking how responsibility could be “rolled back” without making the individual passive or expecting institutions to “solve matters”?

While most of the literature is interested in what neo-liberalism “does” to education, pupils and students, there are a few exceptions that discuss in what way the position of the teacher in particular has changed. Ball (2003) demonstrates how technologies of enterprise reform in the world of school produce new kinds of teacher subjects that are governed through performativity. In line with the principles of performativity, the teacher takes on the role of a performative worker who is expected to have a passion for excellence and performance competition. Education is then seen as a neo-liberal technology where “results are prioritised over processes, numbers over experiences, procedures over ideas, productivity over creativity” (Ball, 2003, p. 91). The teacher is no longer someone who first and foremost cares about knowledge dissemination and the student, but someone who highlights “front impressions” as presentations (Ball, 2003, p. 224). Effectiveness takes precedence, second-ordering honesty and ethical practices, and replacing authenticity with “plasticity” (Ball, 2003, p. 225). This may desocialize knowledge and knowledge relations, turning knowledge into an “object” instead of an embodied experience. Thus, the educational project is left hollow, challenging the very notion of academic work and education. Ten years later, Ball and Olmedo (2013) follow up on this study, in discussing teachers’ possibilities to resist these practices of performativity.

In the critical pedagogy literature, entrepreneurship as the route towards freedom and creativity is problematized. Instead, we are invited to make a U-turn, whereby we discern how we are governed through entrepreneurial freedom. Desire turns into a technology that operates through the enterprising self and those governed are not so much obedient workers as they are to become reflexive knowledge workers. There is freedom to be gained. But using this freedom may also serve those in power and sustain dominant power structures. We should take this into consideration in the making of a more critical entrepreneurship education.

Contours for critical entrepreneurship education

In this chapter we offer our sketch of the contours for a field of a critical entrepreneurship education (CEE). What we have addressed so far is how we learn from EE how entrepreneurship has in fact opened up to embrace “more” in the sense of inviting students to take responsibility for themselves and others through learning how to solve problems (also see Dahlstedt & Fejes, 2017) but, more importantly, not to let all the positive connotations that build up entrepreneurship (education) to stand in the way of posing provocative questions (as with critical management education and critical pedagogy). Engaging in CEE could spur ourselves, as entrepreneurship educators, along with our students, to ponder whether there are other ways to live the present than the standard entrepreneurial way. As a next step we have consulted CES, to become aware of the need to integrate the sceptical view of entrepreneurship with the hopeful approach of “remodelled” entrepreneurship. In our interpretation, this implies an interplay between deconstruction and reconstruction. The following three principles may guide us to bring the interplay between deconstruction and reconstruction into our educational approaches, purposes and content:

1 First, we should assert that although the enterprising self operates through a productive power, which may be difficult to resist, there is always room for distance and resistance (cf. Ball & Olmedo, 2013). Resistance, however, requires us to learn “the rules of the game”. From the perspective of critical entrepreneurship pedagogy, the game does not refer to “business making” but to the game of “governing through entrepreneurial freedom”. As teachers, we could introduce students to the literature of critical entrepreneurship studies, as well as to the concepts of critical pedagogy, helping them to understand the principles and providing them with a new perspective of how entrepreneurship may work. At first it may be enough to show them novel aspects of entrepreneurship and to help them digest the fact that there are also “dark sides” to it. In the next step they could become acquainted with the analytical concepts of, for example, neo-liberalism, governmentality and the enterprising self. Equipped with these analytical concepts they could, themselves, begin to analyse cases of their own interest and train their ability for critical reflection. In shaping their futures, this should help them to find more thought-out, aware solutions – for themselves, for organizations and for society.

2 Second, creativity should be prioritized over productivity and performativity. This may require involving students in play and becoming, and offering students a space for creative work that will not be assessed according to the “business scale”, but that opens up for them to explore new perspectives, stories, connections and responsibility. Creativity could pave the way for curiosity, for motivation to learn (for the sake of learning) and for growing mutual relations with peer students from different societal collectives. If creativity is disconnected from the productivity expectancies, solving problems could be turned around to become a method for teaching and learning rather than the “productivity goal” of a student with such skills.

3 Third, resisting EE to propel neo-liberalism is different from past struggles as we then need to resist our own practices and confront ourselves at the centre of our discomforts (Ball & Olmedo, 2013). As EE educators we can learn about what it means to resist the neo-liberal educational practices foisted upon us. By recognizing how we are exposed to the productive power to perform we can slowly start to see a way to turn this into other directions (again, reconstruction). This can be done by enacting entrepreneurship education in line with the first and second recommendations (above) but we should not forget the importance of also discussing the matter with colleagues, of sharing ideas, of finding common strategies and of supporting each other in setting boundaries that may open up for another scene where we (teachers and students) can be engulfed by knowledge for the sake of knowledge, and aware that “the future” is not inevitable but part of our creations.

Based on these principles we can see the shape of a “field” in which EE and CEE are connected. Entrepreneurship education has been opened up from a narrow “business approach” to embrace a wider approach with the ambition to teach (young) people how they can manage life itself. This has involved a move from understanding the entrepreneur of the self to understanding entrepreneurship as a collective effort and as having social and societal consequences. Entrepreneurship changes from the idea of building one’s kingdom to an understanding of engaging in an entrepreneurship for the other (cf. Jones & Spicer, 2009). This shows a need to move from understanding the doing of entrepreneurship from particular events where successful entrepreneurs are elevated and celebrated (e.g. Dragons’ Den, entrepreneurship awards, etc.) in a “peacock kind of way” (Bill, Jansson & Olaison, 2010) to understanding the mundane practices of entrepreneuring where “worker ants” blend pleasure with struggles (Bill et al., 2010) and where dialogue outclasses pitch and monologue at the scene (also see Denise Fletcher’s prologue). These shifts require a move from “playing the rules of the business game” to understanding how the rules can be played with (Berglund & Gaddefors, 2010). Altogether this takes us towards new understandings of IFTA. We will now return to IFTA and see how it might incorporate a critical take on EE.

Taking named displacements into account we can sketch a shift with regard to IFTA. The “for” of EE changes from learning about starting up a business to nurturing students towards becoming aware decision makers. The “in” of entrepreneurship education changes from making business and business making to enacting entrepreneurship in some form (e.g. through projects, through NGOs, setting up an artistic performance, enacting flash mobs, social engagement and interventions, making films, etc.). The “about” of entrepreneurship education changes from adhering to the grand narrative to problematizing the same, perhaps with using the knowledge provided by critical entrepreneurship pedagogy. The “through” of entrepreneurship education changes from instructions and (business) tools to engaging with students in dialogue and critical reflection. Together this builds an “IFTA 2.0” (see Figure 1.1).

Introducing the book chapters

This section introduces the individual chapters in the book, and relates them to the contours that we have sketched. We can assure the reader that the various contributions offer a rich diversity of approaches, pedagogies and ways of raising questions that testifies to how homogeneity (see Denise Fletcher’s prologue) becomes a matter of the past. Experimentation with criticality in the classroom is happening “out there”, and many fresh and innovative learning experiences are offered by the contributors, including their honest accounts of the resistance and struggles they encounter in doing so.

First, from Richard Tunstall we learn more about how entrepreneurship has actually and effectively found its way into the very core of the university. In Chapter 1, Education or Exploitation? Reflecting on the Entrepreneurial University and the Role of the Entrepreneurship Educator, Richard sets the scene in an outstanding way by showing that entrepreneurship is no longer a marginal issue of providing students with a particular kind of education, but has turned into an issue of managing the university through university–business collaborations. One point he makes is that this sets the very idea of the university in motion. He begins by bringing us to a conference, held at a university, which has gathered prominent guests, including academic delegates, small business owners, university spin-off officers, innovation managers of major multinational corporations and a government minister. But uninvited, and less welcome guests, such as protesting students, have also gathered. Through rich empirical vignettes, Richard testifies to how this conflict unfolds over time and involves university staff, media exposure, and even a trial. With the legacy of the university being to enable students to develop their own reasoning skills in a milieu of academic freedom, entrepreneurship did not in this case pass by unnoticed. While some saw it as the redemption of a future for the (entrepreneurial) university, others saw it as the “evil” of capitalism and as the end of the university as it has always been regarded. Richard elaborates further on this dividing line and illustrates alternative ways of framing the purpose of education practice and the role of those involved. By taking the students’ protests seriously he provides insight into how their expectations go beyond that of making a personal career, and are linked more to concerns about the very purpose of higher education. If we accept that entrepreneurship comes as part and parcel of our (entrepreneurial) society we cannot circumvent this topic in education, nor can we take it for granted. Rather, we need to think anew, for how it can be introduced without prohibiting criticism, protests and concerns, and without juxtaposing “academic freedom” with “the entrepreneurial university”?

Figure 1.1 Towards a critical IFTA.

In Chapter 2, Entrepreneurship in Societal Change: Students as Reflecting Entrepreneurs?, Jessica Lindberg and Birgitta Schwartz invite us to attend a course in which entrepreneurship is connected to various societal issues. Introducing global issues through film, lectures and guest lecturers encourages critical questions among students. These questions are reflected upon from both “new” and “conventional” entrepreneurship literature. At the same time, students engage in solving a particular issue, and through an interplay between the literature and the local context they develop practices for societal entrepreneuring. For Jessica and Birgitta, the entrepreneurial learning process is, in addition to being experience-based (the students’ projects), also and importantly a future-oriented thinking process.

Chapter 3, The Reflexivity Grid: Exploring Conscientization in Entrepreneurship Education, by Leona Achtenhagen and Bengt Johannisson, shares Jessica and Birgitta’s concern for “the world at large”. Leona and Bengt argue that reflexivity plays an important role in entrepreneurship education, whether it is in supporting students to become responsible entrepreneurs, or something “broader”, that is to say training them to develop the intuitive insight they will eventually need to determine what is right and wrong both practically and ethically, and in various types of “concrete situations”. They make a plea for a conscious pedagogical approach to advancing reflexivity, allowing students to conscientiously enact not only their own learning but to also contribute to the (local) world in which their learning occurs. They propose three different modes for enacting reflexivity, namely cognitive/emotional, hierarchy/ network and being/becoming, and discuss these modes by offering two concrete learning situations as illustrative of how these modes for enacting reflexivity play out.

In Chapter 4, From Entrepreneurship to Entrepreneuring: Transforming Healthcare Education, Hanna Jansson, Madelen Lek and Cormac McGrath offer an intriguing insight into the world of healthcare and healthcare education. The chapter provides the reader with rich reflections on the struggles involved in introducing entrepreneurship education to that particular world, where the view of entrepreneurship as something bad is particularly pervasive among healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, physical therapists, etc.). Interestingly, they connect education to what is perhaps a more general ability to learn and make sense of acquiring the ability to adjust certain practices, something they deem relevant, vital even, for the Swedish healthcare sector. This idea has invoked a particular take on entrepreneurship education, as they have proceeded to develop an EE course for their institution. Using Bourdieu’s habitus to define, deconstruct and redefine what is meant by EE, they offer rich reflections on how they enact a pluralistic and nuanced conceptualization of EE in healthcare.

Taken together, these three chapters offer examples of how we can evoke students (and colleagues, as with Chapter 4). These chapters pointedly aim to generate responses, which for us would be a first move towards the kind of awareness that we see in our contours for a critical entrepreneurship education.

In Chapter 5, A Space on the Side of the Road: Creating a Space for a Critical Approach to Entrepreneurship, Pam Seanor offers a very personal story of how she struggles to bring criticality into her classroom. Her view on criticality is that of building awareness; there is never just one reality of entrepreneurship and of creating sensitivity for the differences in entrepreneurship. Pam meets considerable (varieties of) resistance, not only from students but also from colleagues. Her tactic has been – literally – to try to create space for her critical approach to entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education. This chapter may be a good starting point if you are new to the life-world of the (critical) entrepreneurship educator. Pam raises interesting and relevant questions relating not only to the classroom but also to how to open up conversations with colleagues in allowing for “other” interpretations and conceptualizations of entrepreneurship, engaging them in a dialogue that might spur them on to realizing that they too can resist their own practices.

In Chapter 6, Conceptual Activism: Entrepreneurship Education as a Philosophical Project, Christian Garmann Johnsen, Lena Olaison and Bent Meier Sørensen provide us with insightful thoughts on how philosophy can challenge and invite students to rethink and re-enact entrepreneurship. The question they ask is how philosophy can become a productive force in the teaching of entrepreneurship in business schools. Through exploring their own practices and guiding the reader through two didactic approaches they have developed and experimented with, they provide us with a didactic approach tool which they call “conceptual activism”. This approach implies deploying philosophical concepts in such a way that it sensitizes students to their own experiences and discourses on entrepreneurship. Christian, Lena and Bent take us on a tour to their classroom experiences where the two approaches are enacted. In one they use art and a mode of juxtaposition to evoke new “images” of entrepreneurship, and in the other the success/failure dialectics are problematized using Kristeva’s concept of the abject. From these examples we learn how the teachers’ own reflections on philosophy are translated to their interactions with students, who are challenged to unlock alternative viewpoints with regard to key features of entrepreneurship discourses, such as agency, creation, success and failure.

Chapters 5 and 6 together explicitly set out to move (understandings of) entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurship education. They do so by experimenting and offering new “thinking tools”.

In Part IV we find three chapters that also set out to move students, but with explicit considerations with regard to how students can be challenged and moved out of their “comfort zones”, so as to create room for distance and resistance.

In Chapter 7, Bringing Gender In: The Promise of Critical Feminist Pedagogy, Sally Jones gives an informed, insightful and detailed illustration of how she challenges, and sometimes provokes, students to reflect upon the gendered entrepreneurship discourse. By introducing entrepreneurship from a feminist theoretical perspective she involves students in making their own (gendered and other) presumptions visible, both to themselves and others. With the two concepts of “stereotype threat” and “stereotype lift” she invites the reader to reflect upon how teachers may reproduce a gendered, ethnocentric, racist and ageist entrepreneurship discourse. Yet, through employing different didactic approaches, she invites herself, together with the students, to not only reflect upon current gendered practices but also to reconsider how to alter those that they have come to find problematic. From Sally we learn that gendered entrepreneurship discourse requires reflection, and that that very reflection is underpinned by a critical awareness that can be used to analyse and become aware of not only gender but also other dysfunctionalities that entrepreneurship discourse may propel. “Bringing gender in” forced her to experiment with didactic approaches, which helped her and her students to challenge mainstream accounts and practices of entrepreneurship, and “beyond”.

In Chapter 8, Entrepreneurship and the Entrepreneurial Self: Creating Alternatives Through Entrepreneurship Education?, Annika Skoglund and Karin Berglund discuss a critical entrepreneurship course entitled “Entrepreneurship and the Entrepreneurial Self” (designed for master’s students). Entrepreneurship is brought into the course in relation to Foucault’s notion of “productive power”, and to how “freedom” has become linked to a creation of “the social” and “the economic”, to (seemingly) open up possibilities for self-creation. Annika and Karin engage their students in critical reflections on political dimensions, human limits, alternative ideals and the collective efforts that are part of entrepreneurial endeavours. They provide the readers with a detailed description of how the course is set up, including the various assignments they have designed to engage the students in critical learning. The course addresses not only the emphasis being placed on the economic sphere in neo-liberal societies but also how this gives rise to “alternative entrepreneurships” in a way that witnesses how an abundance of entrepreneurial selves unfolds. Annika and Karin assert the need to interrogate this emergence of “rejuvenated and upgraded entrepreneurial selves” in a way that unsettles the spread of these alternative forms.

In Chapter 9, Between Critique and Affirmation: An Interventionist Approach to Entrepreneurship Education, Bernhard Resch, Patrizia Hoyer and Chris Steyaert also argue that it is not enough to “simply” question the optimistic politics of entrepreneurship education. Rather, this is an interplay between critique and affirmation, enabled by “an interventionist approach”. Their interventions aim at disentangling and reassociating time and space, bodies and motions, people and materials, and we constantly add new elements to the equation in what they call “sometimes curious ways” to open up for unusual learning formats which push towards critical reflection as well as experimenting with aesthetic, material, spatial and embodied ways of learning. They offer a description and reflection of a course in which they set out to challenge some of the university’s stabilized preconditions, take “critical walks”, engage students in creative group performances, and invite them to move and dance. Patrizia, Bernhard and Chris illustrate how their interventionist pedagogy generates affectual flows that “may even result in a fumbling reinvention of teaching itself”.

The chapters in Part V once again testify to how encouraging students to get out of their comfort zones and start to see and experience things differently takes time, and comes with discomfort, disruption and resistance – on the part of the students as well as the educators. It invites teachers to rethink their practices, and invent new ones. And it invokes the need to have dialogues.

In Chapter 10, Moving Entrepreneurship, Karen Verduijn engages students in dialogues on the fluid, ephemeral and indeterminate nature of entrepreneuring. The aim is to stimulate students’ curiosity and to move them towards new understandings of what it means to enact entrepreneuring. This is accomplished – based upon process ontology – by introducing students to a film project where their assignment is to produce a film which questions dominant assumptions of the entrepreneur (as a particular person), of entrepreneurship (as a planned and manageable process) and of the result (as a predetermined goal). The approach challenges students’ understandings of entrepreneurship and may at times, and with regard to students’ previous educational experiences, appear uncomfortable and sometimes even incomprehensible. The approach thus moves students out of their comfort zones and introduces them to a new setting where educational concepts of examination, goals and results need to be reinterpreted. Apart from bringing the reader to the classroom to show in detail how this approach can enrich entrepreneurship education, Karen also addresses the struggles and turmoil it may bring about for the educators, and elaborates on how they form valuable learning experiences that can be brought back into the dialogue with students.

In Chapter 11, On Vulnerability in Critical Entrepreneurship Education, Anna Wettermark, André Kårfors, Oskar Lif, Alice Wickström, Sofie Wiessner and Karin Berglund emphasize the need to have mutual learning taking place in our classrooms. The chapter develops thoughts on vulnerabilities and possibilities in teaching entrepreneurship, and includes reflections of students who have taken the course, on which deliberate space is created for the “outing” of vulnerabilities, both the teacher’s and the students’. The chapter continues with discussions on the self, as explained in Chapter 9. It offers an opportunity to witness how students take up critical notions about the self, in relation to other(s), and in doing so offers an inspiring example of how dialogue can be enacted, and student awareness fostered.

The epilogue, by Ulla Hytti, connects to the various chapters in the book by discussing how critical entrepreneurship education could take the form of resisting the tendencies towards a “McEducation”, a tendency in which students are seen as consumers, with the right to have an entrepreneurship education. Ulla’s contribution, as well as others in the volume, questions this tendency, and argues that bringing in the “why” may prove a way forward.

Together, the contributions provide us with a platform from which we can start to meet the challenges that entrepreneurship education faces in contemporary society, and a basis from which to continue to bring criticality in the classroom, whether through evoking and/or through moving and/or through challenging and/or through having dialogues with students. With this volume we would like to affirm to other entrepreneurship educators that we no longer have to experiment in isolation but that in sharing our thoughts, concerns and ideas of a critical entrepreneurship education we have a community to learn from and with, which serves to break up our sense of isolation.

References

Achtenhagen, L. & Welter, F. (2011). “Surfing on the ironing board” – The representation of women’s entrepreneurship in German newspapers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(9–10), 763–786.

Al-Dajani, H. & Marlow, S. (2013). Empowerment and entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 19, 503–524.

Alvesson, M. & Willmott, H. (1996). Making sense of management: A critical introduction. London: SAGE.

Armstrong, P. (2005). Critique of entrepreneurship: People and policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ball, S.J. (2003). The teachers’ soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Educational Policy, 18(2), 215–228.

Ball, S.J. & Olmedo, A. (2013). Care of the self, resistance and subjectivity under neoliberal governmentalities. Critical Studies in Education, 54(1), 85–96.

Banerjee, S.B. & Tedmanson, D. (2010). Grass burning under our feet: Indigenous enterprise development in a political economy of whiteness. Management Learning, 41(2) 147–165.

Barinaga, E. (2016). Activism in business education. In C. Steyaert, T. Beyes & M. Parker (Eds), The Routledge companion to reinventing management education (pp. 298–311). Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge.

Barry, A. & Osborne, T. (1996). Foucault and political reason: Liberalism, neo-liberalism, and rationalities of government. Oxford: University of Chicago Press.

Beaver. G. & Jennings, P. (2005). Competitive advantage and entrepreneurial power: the dark side of entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12, 9–23.

Bendix Petersen, E. & O’Flynn, G. (2007). Neoliberal technologies of subject formation: A case study of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme. Critical Studies in Education, 48(2), 197–211.

Berglund, K. (2013). Fighting against all odds: Entrepreneurship education as employability training. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization, 13, 717–735.

Berglund K. & Gaddefors J. (2010). Entrepreneurship requires resistance to be mobilized. In F. Bill, B. Bjerke & A.W. Johansson (Eds), (De)mobilizing entrepreneurship – exploring entrepreneurial thinking and action (pp. 140–157). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Berglund, K., Johannisson, B. & Schwartz, B. (Eds) (2012). Societal entrepreneurship: Positioning, penetrating, promoting. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Berglund, K., Lindgren, M. & Packendorff, J. (2017). Responsibilising the next generation: Fostering the enterprising self through de-mobilising gender. Organization, 1350508417697379.

Berglund, K. & Skoglund, A. (2016). Social entrepreneurship: To defend society from itself. In A. Fayolle & P. Riot (Eds), Rethinking entrepreneurship: Debating research orientations (pp. 57–77). New York, NY: Routledge.

Beyes, T. & Michels, C. (2011). The production of educational space: Heterotopia and the business university. Management Learning, 42, 521–536.

Bill, F., Jansson, A. & Olaison, L. (2010). The spectacle of entrepreneurship: A duality of flamboyance and activity. In F. Bill, A. Jansson & L. Olaison (Eds), (De)mobilizing the entrepreneurial discourse: Exploring entrepreneurial thinking and action (pp. 158–175). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Bragg, S. (2007). “Student voice” and governmentality: The production of enterprising subjects. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 28(3), 343–358.

Brown, W. (2003). Neo-liberalism and the end of liberal democracy. Theory and Event, 7(1).

Calas, M.B., Smircich, L. & Bourne, K.A. (2009). Extending the boundaries: Reframing “Entrepreneurship as Social Change” through feminist perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 552–569.

Choo, K.L. (2007a). Can critical management education be critical in a formal higher educational setting? Teaching in Higher Education, 12(4), 485–497.

Choo, K.L. (2007b). The implications of introducing critical management education to Chinese students studying in UK business schools: Some empirical evidence. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31(2), 145–158.

Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: An essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 99–112.

Costa, A.S.M. & Saraiva, L.A.S. (2012). Hegemonic discourses on entrepreneurship as an ideological mechanism for the reproduction of capital. Organization, 19(5), 587–614.

Costea, B., Amiridis, K. & Crump, N. (2012). Graduate employability and the principle of potentiality: An aspect of the ethics of HRM. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 25–36.

Currie, G., Knights, D. & Starkey, K. (2010). Introduction: A post-crisis critical reflection on business schools. British Journal of Management, 21, 1–5.

Dahlstedt, M. & Hertzberg, F. (2014). In the name of liberation. Notes on governmentality, entrepreneurial education, and life-long learning. European Education, 45(4).

Dahlstedt, M. & Tesfahuney, M. (2011). Speculative pedagogy: Education, entrepreneurialism and the politics of inclusion in contemporary Sweden. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 8(2), 249–274.

Dahlstedt, M. & Fejes, A. (2017). Shaping entrepreneurial citizens: A genealogy of entrepreneurship education in Sweden. Critical Studies in Education, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/ 17508487.2017.1303525.

Dey, P. & Steyaert, C. (2007). The troubadours of knowledge: passion and invention in management education. Organization, 14(3), 437–461.

Down, B. (2009). Schooling, productivity and the enterprising self: Beyond market values. Critical Studies in Education, 50(1), 51–64.

Essers, C. & Benschop, Y. (2009). Muslim businesswomen doing boundary work: The negotiation of Islam, gender and ethnicity within entrepreneurial contexts. Human Relations, 62(3), 403–423.

Essers, C. & Tedmanson, D. (2014). Upsetting “others’ in the Netherlands: Narratives of Muslim Turkish migrant businesswomen at the crossroads of ethnicity, gender and religion. Gender, Work & Organization, 21, 353–367.

Essers, C., Dey, P., Tedmanson, D. & Verduijn, K. (Eds) (2017). Critical perspectives on entrepreneurship. Challenging dominant discourses. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fayolle, A. (2013). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(7–8), 692–701.

Fletcher, D.E. (2006). Entrepreneurial processes and the social construction of opportunity. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 18, 421–440.

Fletcher, D.E. & Selden, P. (2015). A critical review of critical perspectives in entrepreneurship research. In H. Landström, A. Parhankangas, A. Fayolle & P. Riot (Eds), Challenging the assumptions and accepted research practices in entrepreneurship research. London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1978/1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon & P. Miller (Eds), The Foucault effect – studies in governmentality with two lectures and interviews with Michel Foucault (pp. 87–104). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

du Gay, P. (2004). Against “enterprise” (but not against “enterprise”, for that would make no sense). Organization, 11, 37–57.

Gibb, A. (2002). In pursuit of a new “enterprise” and “entrepreneurship” paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International Journal of Management Reviews, 4(3), 233–269.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henry, C., Hill, F. & Leitch, C.M. (2003). Entrepreneurship education and training. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hjorth, D. (2011). On provocation, education and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23, 49–63.

Hjorth, D. (2013). Absolutely fabulous! Fabulation and organization-creation in processes of becoming-entrepreneur. Society and Business Review, 8, 205–224.

Hjorth, D. & Johannisson, B. (2007). Learning as an entrepreneurial process. In A. Fayolle (Ed.), Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education, volume 1 (pp. 46–66). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hjorth, D. & Steyaert, C. (Eds). (2010). The politics and aesthetics of entrepreneurship: A fourth movements in entrepreneurship book. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hjorth, D., Jones, C. & Gartner, W.B. (2008). Recontextualising/recreating entrepreneurship. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(2), 81–84.

Holmgren, C. (2012). Translating entrepreneurship into the education setting: A case of societal entrepreneurship. In K. Berglund, B. Johannisson and B. Schwartz (Eds) Societal entrepreneurship: Positioning, penetrating, promoting (pp. 214–327). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Jack, S., Drakopoulou Dodd, S. & Anderson, A.R. (2008). Change and the development of entrepreneurial networks over time: A processual perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 20(2), 125–159.

Jamieson, I. (1984). Schools and enterprise. In A.G. Watts & P. Moran (Eds), Education for enterprise (pp. 19–27). Cambridge: CRAC, Ballinger.

Jones, C. & Spicer, A. (2005). The sublime object of entrepreneurship. Organization, 12(2), 223–246.

Jones, C. & Spicer, A. (2009). Unmasking the entrepreneur. London: Edward Elgar.

Kirby, D. (2007). Changing the entrepreneurship education paradigm. In A. Fayolle (Ed.), Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education (pp. 21–45).

Korsgaard, S. (2011). Entrepreneurship as translation: Understanding entrepreneurial opportunities through actor-network theory. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(7–8), 661–680.

Kuratko, D.F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 577–598.

Leffler, E. (2009). The many faces of entrepreneurship: A discursive battle for the school arena. European Educational Research Journal, 8(1), 104–116.

Lemke, T. (2001). “The birth of bio-politics”: Michel Foucault’s lecture at the Collège de France on neo-liberal governmentality. Economy and Society, 30(2), 190–207.

Marsh, D. & Thomas, P. (2017). The governance of welfare and the expropriation of the common: Polish tales of entrepreneurship. In C. Essers, P. Dey, D. Tedmanson & K. Verduijn (Eds), Critical perspectives on entrepreneurship. Challenging dominant discourses. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nabi, G., Linan, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N. & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299.

Nayak, A. & Chia, R. (2011). Thinking becoming. Process philosophy and organization studies. Philosophy and Organization Theory Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 32, 281–309.

Nodoushani, O. & Nodoushani, P.A. (1999). A deconstructionist theory of entrepreneurship: A note. American Business Review, 17(1), 45–49.

O’Connor, A. (2013). A conceptual framework for entrepreneurship education policy: Meeting government and economic purposes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(4), 546–563.

Ogbor, J.O. (2000). Mythicizing and reification in entrepreneurial discourse: ideology-critique of entrepreneurial studies. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 606–635.

Olaison, L. & Sorensen, B. (2014). The abject of entrepreneurship: Failure, fiasco, fraud. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 20, 193–211.

Ozkazanc-Pan, B. (2014). Postcolonial feminist analysis of high-technology entrepreneuring. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 20(2), 155–172.

Peters, M. (2001). Education, enterprise culture and the entrepreneurial self: A Foucauldian perspective. Journal of Educational Enquiry, 2(2), 58–71.

Pettersson, K., Ahl, H., Berglund, K. & Tillmar, M. (2017). In the name of women? Feminist readings of policies for women’s entrepreneurship in Scandinavia. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 33, 50–63.

Pittaway, L. & Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25(5), 479–510.

Rehn, A., Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. & Lindahl, M. (2013). Challenging the myths of entrepreneurship? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(7–8), 543–551.

Scharff, C. (2016). The psychic life of neoliberalism: Mapping the contours of entrepreneurial subjectivity. Theory, Culture & Society, 33(6), 107–122.

Spicer, A. (2012). Critical theories of entrepreneurship. In K. Mole & M. Ram (Eds), Perspectives on entrepreneurship. A critical approach. London: Palgrave.

Steyaert, C. & Hjorth, D. (Eds). (2003). New movements in entrepreneurship, volume 1. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Steyaert, C. & Hjorth, D. (Eds). (2006). Entrepreneurship as Social Change (Vol. 3). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Taatila, V.P. (2010). Learning entrepreneurship in higher education. Education+ Training, 52(1), 48–61.

Tedmanson, D., Verduijn, K., Essers, C. & Gartner, W.B. (2012). Critical perspectives of entrepreneurship research. Organization, 19(5), 531–541.

Thrane, C., Blenker, P., Korsgaard, S. & Neergaard, H. (2016). The promise of entrepreneurship education: Reconceptualizing the individual–opportunity nexus as a conceptual framework for entrepreneurship education. International Small Business Journal, 34(7), 905–924.

Verduijn, K., Dey, P., Tedmanson, D. & Essers, C. (2014). Emancipation and/or oppression? Conceptualizing dimensions of criticality in entrepreneurship studies. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 20(2), 98–107.

Verduijn, K. (2015). Entrepreneuring and process. A Lefebvrian perspective. International Small Business Journal, 33(6), 638–648.

Vrasti, W. (2009). How to use affective competencies in late capitalism. In British International Studies Association (BISA) Annual Conference, University of Leicester (pp. 14–16).

Ziegler, R. (2011). An introduction to social entrepreneurship. Cheltenham and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.