2 Entrepreneurship in societal change

Students as reflecting entrepreneurs?

Jessica Lindbergh and Birgitta Schwartz1

Introduction

The focus on entrepreneurship has been seen as a positive economic activity (Tedmanson, Verduijn, Essers & Gartner, 2012), not only bringing about innovations in the business and at the market but also as a way to develop societies (e.g. Berglund, Johannisson & Schwartz, 2012). However, entrepreneurship education in business schools is still mainly related to more conventional forms of entrepreneurship, with a focus on starting a company based on the innovation of a new product or service (Fiet, 2000; Gartner & Vesper, 1994; Gorman, Hanlon & King, 1997; Henry, Hill & Leitch, 2005). Accordingly, students learn how to start a company, find a customer demand and make their company profitable and successful on the market. Not on our course. We aim to give the students a broader awareness of the societal issues that today’s society is facing, frequently caused by the traditional economical reasoning, such as growth and more efficient production processes. The issues that are targeted are pollution, poor working conditions and overconsumption, but also other societal issues more related to integration, and mental health.

In this chapter, we describe a course in which we try to involve the students in developing knowledge of how to find solutions to problematic societal issues through entrepreneurship. One way that we visualize societal issues to the students is with the help of film material that presents the activities of different stakeholders in the production of consumer goods, such as shoes and clothing. We believe the students can quite easily relate and identify to such goods as consumers. Please come with us to the classroom where one of our lectures is being given.

The students enter the classroom for a lecture on entrepreneurship and context. At the beginning of the lecture, the teacher tells the students that she will show a documentary about the clothing and shoe industry in India. Before the film starts, the students are given different roles as stakeholders, i.e. suppliers, retailers, customers, NGOs and workers. The teacher also presents a number of questions for the students to reflect upon while watching the documentary, such as the actors’ responsibilities and what opportunities and hindrances there are to changing the situations of workers and farmers. The film begins with some interviews with large Swedish retailers explaining that their clothes and shoes are produced in India and how much they know (or don’t know) about their suppliers and how their products are produced. In the next scene, we follow the reporter to India and we see child labour, workers suffering from severe health problems, and how the pollution of water caused by the Swedish companies’ local suppliers creates toxic drinking water and destroys farm land. The reporter interviews factory owners, workers, farmers and NGOs about these problems. In the next scene of the documentary we jump back to the Swedish context and the reporter confronts the retailers about the appalling working conditions and environmental consequences. The students watching the film see different responses. Some of the retailers are very honest and reflective on the Western world’s exploitation of workers in developing countries, while others relate to the problems from a business perspective and how to handle the problems by controlling the suppliers using codes of conduct.

After the film, the students are asked to discuss their stakeholders’ responsibilities, opportunities and hindrances in this situation and to come up with solutions. The students suggest, for example, increasing the control of suppliers, and NGOs doing voluntary work to help their workers. But they also see many hindrances to change for the actors, such as lack of laws, regulations and norms that ensure workers’ rights and protect the environment. The students’ solutions are often grounded in their own cultural context. They see great difficulties in making an impact as a single customer. Instead, they argue that customers need to organize themselves into larger groups in order to be a stronger force for changing the situation.

The solutions suggested by the students have difficulty breaking free from stakeholders’ existing logics, as presented in the documentary, and therefore there is little discussion on new ways of creating change. Instead, the solutions emphasize more of the same, i.e. stronger institutions to enable more control and stronger NGOs. It is clear that this is a documentary that upsets some students in various ways. This is evident not so much in that they voice it in the classroom but rather that they come forward during the break to discuss it with the teachers. Other students seem to be more aware of the problems, as a result of similar documentaries and/or personal experience as a volunteer in a developing country. In relation to this lecture we always end up discussing their own decision-making while shopping. Very few students believe that they can influence producers and retailers and they also explain that “doing good” is very expensive for poor students.

After a break, the lecture continues with the presentation of a research project about a social entrepreneur who produces organic and fair trade cotton clothing and bags in India with the aim of solving the environmental and social issues presented in the film. The students meet the entrepreneur’s struggle to combine her social mission with running a for-profit company, all with the purpose of presenting the complexity of doing societal entrepreneurship.

With this episode, we wanted to bring the reader into the classroom to get an idea of what the students are asked to discuss and reflect upon in relation to entrepreneurship and societal change. Today, several kinds of entrepreneurship are evolving related to how individuals, organizations and nations try to solve problematic issues in society and change society with regard to, for example, social and environmental issues. This is defined in this chapter as societal entrepreneurship (Berglund et al., 2012). In order for students to understand societal entrepreneurship and for us as teachers to encourage students or comply with students’ societal engagement, there is a need to widen entrepreneurship education, i.e. to take more than simply the economic aspects into consideration. To accomplish this task students must embrace a broader view of entrepreneurship. For example, what success factors related to conventional entrepreneurship and enterprising, such as growth and profit maximization, can have consequences for society, such as social problems and environmental problems (Söderbaum, 2000, 2009). As the lecture also highlights, the difficulty for entrepreneurs following their social or environmental mission entails a struggle for themselves and their enterprises when striving to survive on the market (Smith, Knapp, Barr, Stevens & Cannatelli, 2010; Berglund & Schwartz, 2013).

For that reason, we find that it is important that entrepreneurship education allows the students to study and reflect upon dark and bright sides of conventional entrepreneurship and societal entrepreneurship. This is done by studying literature and real cases as well as working in student projects. In these projects the students reflect on their own entrepreneurial process, and the challenges and risks of their own solution, when trying to organize how to solve a social or environmental problem in society. In class, the students in the group project assignment also learn from each other when reviewing and discussing each other’s projects. Similar to Rae’s argument (1999), our aim is to combine the three sources of entrepreneurial learning: formal (theoretical learning), active (practical learning) and social (learning from others).

The purpose of the chapter is to describe our process of developing and teaching a course in societal entrepreneurship and how the students appear to receive the course and to learn. In this chapter, we illustrate how we strive to combine formal, active and social learning (Rae, 1999) on an undergraduate course of 7.5 ECTS credits given during a period of 4.5 weeks for bachelor’s students in business administration and how the students understand and experience the topic and course. This is done by problematizing how students perform their project assignment and also how students understand entrepreneurship at the beginning of the course and their evaluation of such experience at the end of the course. We have material from five courses given during the years 2014–16, including notes of student expectations collected during the course introduction and evaluation in written forms from three course occasions collected on the final day of the course.

Our intentions with regard to the course

The overall aim of the Entrepreneurship in Societal Change (ENSO) course is for the students to understand societal entrepreneurship and to express how it may be enacted in various contexts. In addition, the course focuses on the interplay between entrepreneurship and societal change, i.e. to what extent entrepreneurship plays a part in changing society. During the course we discuss and study conventional business entrepreneurship and societal entrepreneurship, with a particular interest in societal entrepreneurship and the challenges these entrepreneurs meet. Such entrepreneurship focuses not only on growth and profit as a success factor but also includes other factors deemed equally important, such as finding new solutions for creating a common good, fighting poverty, maintaining cultural heritage, and implementing a transition to a more environmentally sound society.

The students are assessed by means of three assignments: a group project, which is worth 30 per cent, a review of another group report, worth 10 per cent, and a final written exam, worth 60 per cent. These assignments are related to our pedagogical underpinnings of how to teach and help students to reflect upon entrepreneurship and societal change and can be compared to Rae’s (1999) discussion on entrepreneurial learning as referred to in Edwards and Muir’s (2005) article. Rae argues (1999) that entrepreneurial learning stems from three sources, namely theoretical learning (formal), practical learning (active) and learning from others (social). The sources can be translated into activities that we do on the course, such as providing theoretical understanding through diverse literature and lectures, gaining practical experience both through the project and through learning from the others by sharing their projects with the other course participants, as well as guest lecturers who share their experience of social entrepreneurship. These activities should not be seen as isolated and unrelated to each other but rather as part of a learning cycle, where different practices are important for the understanding of theory and vice versa (Kolb, 1984).

The learning goals on the course and assessed by the three assignments can also be related to Rae’s (1999) three sources of learning – formal, active and social. The learning goals related to gaining knowledge and understanding relate to both formal and active learning, such as:

• Identify, describe and explain forms of entrepreneurship in relation to contexts and societal change (formal).

• Recognize different entrepreneurial contexts (active).

Learning goals for skills and abilities relate to all learning sources but mainly to active and social sources, such as:

• Apply perspectives from management and organizational theories in order to investigate the challenges of doing entrepreneurship for societal change (formal and active).

• Identify entrepreneurial challenges and suggest solutions regarding environmental or social problems with focus on societal change (active, social).

• Show ability to plan and execute, individually and in a group, a defined entrepreneurial project (active and social).

The final theme of learning goals related to judgement and approach relates to all three sources of learning and is expressed as:

• Critically analyse and evaluate different forms of entrepreneurship in relation to context (formal, active, social).

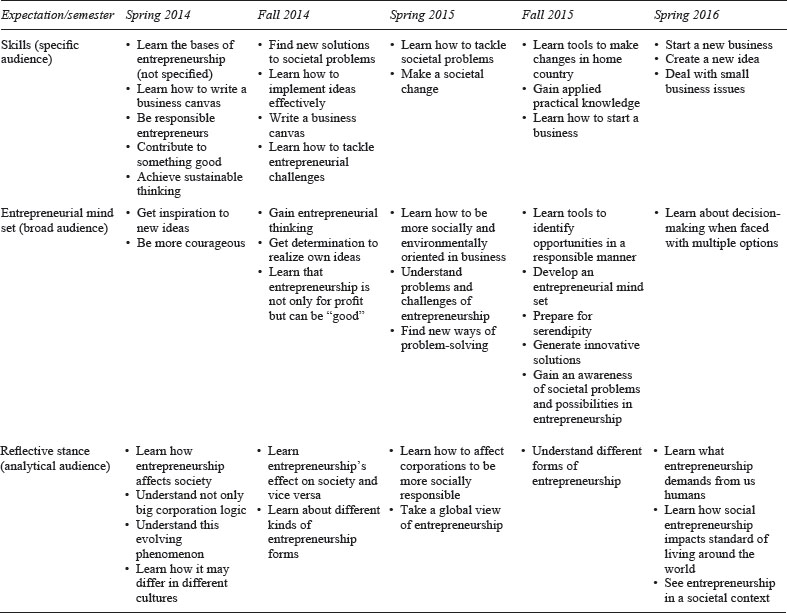

The audience of entrepreneurship education

Entrepreneurship education and training have different content and perspectives in programmes and courses (Henry et al., 2005). These variations depend on the nature of the target audience (students at college or university, potential entrepreneurs, business owners) as well as the expectations from students or the fact that there are different target markets for these courses (Gorman et al., 1997). Some audiences believe that what should be included in potential entrepreneurship courses is a more practically oriented “how to start your own business”. But they also mention issues such as marketing, entrepreneurship, business planning, management and financial management and how to assess one’s own entrepreneurial skills, which could improve one’s chances of success (Le Roux & Nieuwenhuizen (1996), referred to in Henry et al. (2005)). These audiences relate to the categories of specific and broad audiences in Table 2.1 below, where the differences between audience and student perceptions of entrepreneurship education are presented. As we can see, there are different audiences. The “specific audience” wants to start a business and to have an insight into how entrepreneurs act and create value. The “broad audience” is more interested in how to develop their entrepreneurial mindset for how to think and learn and to identify, evaluate and organize opportunities (Nielsen, Klyver, Rostgaard & Bager, 2012). There is yet another kind of audience that does not relate to entrepreneurship at all, or that is sceptical towards business. This unaware/sceptical audience is not aware beforehand of what entrepreneurship is and is more sceptical in the sense of questioning the role of business in society. They do not aim to start their own business; rather, they want to be employed in other types of organizations (Berglund, 2014).

Table 2.1 Different audience and student’s perception

| Perception/ audience |

Specific audience | Broad audience | Unaware/ sceptical audience |

| Career ambition | Have real ambition to start a business | Has ambition to work with entrepreneurial issues | Want employment |

| Overall rationale | To understand start-up processes | To develop an entrepreneurial mindset | To understand what it means to be enrolled as part of an entrepreneurial working force |

| Learning needs | Seeking practical and instrumental skills | Seeking an ability to identify, evaluate and organize opportunities | Understanding the consequences of living in an entrepreneurial era |

Source: Nielsen et.al., 2012; Berglund 2014.

Our audience and their expectations of the course

So, what kind of audience do we meet on the course? The students that can choose this course are on programmes within business administration, business administration and political science, and business administration and IT. The course is not mandatory for any of the student categories. It is also open for students taking free-standing courses, of whom a majority are exchange students, primarily from Europe but also a small number of students from Asia and North and South America. The students are generally in their second or third year of bachelor’s studies. The number of students has fluctuated between semesters but a total number of 250 students have been first-time registrants on the course (of whom 45 per cent are exchange students) and a total of 235 students have actually completed the course.

The course is presented to potential students on the school’s web page, and as soon as the students have been enrolled on the course they can download a study guide presenting the course. On the first occasion when the course is introduced, the students are given a lecture on sustainable development and its relation to highand low-income countries and the three societal sectors, i.e. private sector (market), public sector (state) and the non-profit/voluntary sector (civil society), before they are asked to state their expectations of the course and write them on Post-it notes. The following questions are asked to find out about the students’ expectations of the course: What do you want to achieve, get out of, learn from this course? What do you expect from the teachers? What do you expect from your fellow students?

The material on student expectations has been gathered from five semesters, starting with spring 2014 and ending with spring 2016. Over this period of two years we have been interested to find out what kind of preconception the students had about entrepreneurship in general, but also more specifically about entrepreneurship in societal change. Over the years the results have helped us to better understand our audience and to be able to set the stage for introducing several forms of entrepreneurship to the students. In the following table, Table 2.2, we present an overview of the students’ comments regarding their expectations in respect of the first question, what to learn on the course. The statements are not to be seen as individual responses but as general areas of expressed expectations regarding the course (i.e. we do not quantify how many individuals can be related to each statement).

Table 2.2 An overview of students’ expectations of learning needs across five semesters

In an attempt to understand the students’ expectations, we can see that the students fit the criteria of an anticipated audience as defined by Nielsen et al. (2012), i.e. a specific audience whose aim is to acquire the skills to set up a business, and a broad audience with an interest in gaining an entrepreneurial mindset. We can also to some extent find wishes/reasoning similar to that referred to in Berglund’s (2014) third group of audience, the unaware/sceptical audience. However, since the students have made an active choice to enrol on the course, as it is not mandatory for their programme, we perceive that the expectations do not imply that the students are sceptical to entrepreneurship but rather that they are interested in the interplay between society and business in general. Hence, we choose to call them the analytical audience. In Table 2.2 below, we have placed the students from different semesters into three categories that capture the different audiences in Table 2.1. In the first category, we look for different statements referring to the skills of setting up a business (specific audience). The second category captures statements about an entrepreneurial mind set (broad audience) and the third category captures statements that aim to better understand the consequences of living in an entrepreneurial era, which we call a reflective stance (analytical audience).

The fifth time the course was given, prospective students had had time to speak and ask about the course before it started. The presentation on the course’s web page, as well as the format and content in the introductory lecture, remained the same. Perhaps we can therefore assume that some of the students’ expectations at a later stage are more in line with what the course actually covers in regard to entrepreneurship in societal change. This might also be the reason why there is a greater emphasis on learning about sustainable development, social entrepreneurship and societal change and the role of entrepreneurship in society in the later semester than in the first. In the first semester, the students’ primary focus was to learn for entrepreneurship, such as setting up their own business (Jamieson, 1984). However, the expectations of learning entrepreneurial skills have been consistent over time despite its very brief focus in the course presentation on the web (one sentence at the end) as well as little emphasis on such skills, i.e. how to set up a business, for the project work. In the next section, we explain how we organize the course.

In the classroom

The course has several underpinnings, both theoretically and practically, that the students experience through the literature as well as in an actual project. The main course literature is a book, Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice: Paradoxes in Play, written by Nielsen et al. (2012), illustrating the “messy and paradoxical” nature of entrepreneurship by using different entrepreneurial cases. These are discussed using different types of theories and, as such, explaining how different theoretical lenses present different types of paradoxical theoretical reasoning. It is a textbook whose primary target group is undergraduate students and it is structured in four themes: entrepreneurship and the entrepreneur, the entrepreneurial process, the entrepreneurial content and the entrepreneurial context. We have also taken these themes as the structure of our course. The book aims to take a broad view of entrepreneurship and presents the reader with different perspectives on entrepreneurship and its outcomes. It does not, however, in any way discuss the dark sides of any type of entrepreneurship. Students find the book easy to read and we believe that one reason is the very fact that students are the target group and it follows a traditional business discourse. The course literature is also based on articles, some of which are referred to in the book by Nielsen et al. (2012). The thinking is that the students also need to read the original articles, not only other authors’ interpretations of them.

To balance the more conventional view on entrepreneurship we use an additional course book with more context-specific dilemmas that societal entrepreneurs encounter. The book is called Societal Entrepreneurship: Positioning, Penetrating, Promoting by Berglund, Johannisson and Schwartz (2012) and focuses on entrepreneurs acting in and between different society sectors, i.e. the public sector, the private sector and the voluntary/non-profit sector. The book also shows how the sectors’ different logics influence and challenge entrepreneurs and sometimes even create dark sides of entrepreneurship. Students find this book a bit more challenging; the reason could be that its primary target is other academic scholars, even though both students and reflective practitioners are included in the book’s target groups.

Defining the problem and the entrepreneurial solution

In order to make the students reflect on societal issues through more than reading relevant literature and being assessed by means of a written exam, they must also create their own entrepreneurial project in groups of four to five students. The students participate in a collective entrepreneurship process, where they identify an environmental or social problem in an industry or society and define how different actors, from different societal sectors, handle or cause this problem. The aim of the investigation is to find a solution and choose an entrepreneurial form that they will work with in order to solve the issue. This process is initially quite irritating and frustrating for the students, since they themselves have to define a problem they think is important enough to work with. In addition, they also need to define and organize a solution. We know this process takes time, since they first need to decide on a problem and then also dig a lot deeper into the reasons behind the problem and map all the actors connected to the problem. In this process we also tell the students that they cannot copy an existing idea but that it is fine to improve an existing idea and translate and/or redesign it into their chosen context. Nonetheless, some students find the initial creative process very difficult. On one occasion, a group actually plagiarized an existing societal entrepreneurship, the idea as well as the organization, which we interpret as a desperate action. The groups that seem to struggle most with the aim of their idea are those that start out by finding an existing product, often on the Internet, and then try to find the societal problem that the product could help to solve. In contrast, the groups that start by identifying the societal problem (which they are encouraged to do) do better in developing an idea to solve, or at least improving the problematic issue they focus on. The solutions or ideas are also more often related to organizing services rather than developing or innovating a new product for sale, or a new charity.

For the project, we tell them that they can choose to start a business, or a non-profit voluntary organization (NGO), or to be an intrapreneur in a public organization or company. Most often the students choose an NGO as the organizational form, instead of a for-profit initiative. The argument is generally that they do not think that they will gain legitimacy for their organization if it has a for-profit aim. They do not think that the collaborating organizations and/ or donors would trust them if they made a profit for themselves. This view has changed somewhat since we introduced a guest lecturer from a for-profit social enterprise who discusses the issue of making money when doing social entrepreneurship. She questions the view in today’s society that it is OK for companies and their CEOs to make a lot of money from contributing to societal problems, while a CEO of an NGO is not expected to earn a high salary. Her experience as a social entrepreneur gives her a greater legitimacy and seems to change the view of some students on trustworthiness in relation to for-profit. So, on subsequent courses, we saw more student projects that chose a for-profit form, even though some groups stress that in order to be trustworthy their goal is not profit maximization.

The student groups are supervised on two occasions during the course where they discuss how they develop their idea and what challenges they struggle with, both in relation to their idea development and also if they have any collaboration problems among the group members. Since there is a mix of international and Swedish students the societal problem can vary widely according to context, and sometimes cause confusion and tensions on how to describe the problem as well as finding a solution. We frequently see that one or two students eventually dominate the definition of a societal problem and solution. Consequently, in addition to struggling with the process of defining a problem and solution, the other students in the group also struggle to grasp the context in which this problem and solution will be situated.

On the five times we have held the course, we have recognized that the societal problems the students have chosen to work with are often related to their own contexts, such as finding accommodation (e.g. housing for students), difficulties finding jobs, renting out products that are expensive for students or only needed when studying, promoting social issues in schools, or cheap but healthy food for students. The Swedish students have often chosen a problem in Sweden; exchange students have also chosen Sweden but often look for ideas already established in their home countries and then try to translate these ideas to the Swedish context (e.g. selling or producing juice from an unattractive fruit, or exchanging flats between exchange students). The reverse is also common, i.e. that Swedish sustainable solutions are translated to another context related to group members’ home countries, for example a project on recycling water bottles in Thailand.

Becoming entrepreneurs for societal change

During the course we give two workshops. In the first, the entrepreneurial learning source is based on social interaction in which students learn from each other (Rae, 1999). The groups present the problem they will solve and their entrepreneurial idea to the other groups and are given both written and oral comments by another group and by us. In this workshop exercise, the ideas are also discussed in relation to their choice of organizational form, which sector logics to handle and the context in which they will situate their organization and idea. The students are very active in the workshop and take the assigned consultancy role seriously. They can be very creative and critical of each other in developing the ideas further. At this workshop we can see a transformation taking place and students “becoming” societal entrepreneurs when defending their entrepreneurial idea. The first workshop’s exercises also relate to Rae’s (1999) formal learning source, since the reviews and discussions might also contribute to their theoretical understanding.

At the second workshop, we emphasize the active entrepreneurial learning source (Rae, 1999) and the groups work actively on a business model canvas in order to investigate their customers/users, their competitors, collaborations with other actors, costs, financial sources etc. This is an activity that the students engage in with enthusiasm, since the business model canvas tool seems to help them structure their discussions when identifying the different steps in developing their ideas. On this occasion, the financial issues become more evident for the students regardless of which organizational form they chose. This is also when the tension between revenues and social mission becomes obvious.

The process of distancing

The final project report emphasizes the formal entrepreneurial learning source (Rae, 1999). The students are asked to distance themselves a little from their entrepreneurial process by reflecting on their project work when writing the report. They should reflect on their own collective entrepreneurial process with the help of the course literature, such as, for example, their experiences of using a business canvas when developing the idea, and also how they experience their process was created or discovered or both, etc. In addition, the students need to reflect not only on which practical and organizational challenges they need to overcome in the context in which they will act and in relation to different society sectors and their logics, but also if their idea of solving a pressing issue could cause other unwanted societal problems.

The students seem to have some difficulty reflecting on their own entrepreneurial process and their own idea and how to organize their solution. Some groups are better at this than others. The analysis of the entrepreneurship form they have chosen often relates to the legitimacy issues we discussed previously (for-profit vs non-profit) but some reports discuss how their idea could benefit from a specific form. This is often discussed from a user perspective or in relation to collaborators and funders. But two-thirds of the students’ project reports often lack an analysis of the entrepreneurship form in relation to the context and the society sector(s) in which they have chosen to act. Also, there is no mention of how to deal with the logics of different sectors when collaborating with other organizations from other sectors and how this challenges their solution and idea. As mentioned earlier, we find that the students have a problem with the process of distancing in the project report. There might be several reasons for this, such as time pressure or being able to go back and forth between theory and practice in the same report. This is similar to Gartner and Vesper’s (1994) findings that show the difficulty students have in analysing their own actions and thoughts while undertaking activities of developing, for example, a business plan.

In the process of distancing, we ask the students to reflect on critical risks that may come with their project idea. The discussions vary from economic to societal risks that their projects can have and cause. If the students choose the form of a for-profit enterprise, their discussions of risks are related more to profitability, market, competitors, prices and costs. If they choose the form of an NGO initiative instead, they explain the risks as related to legitimacy issues and collaboration problems. There are examples of discussions and reflections of when their own idea could cause other societal problems or consequences, such as, for example, safety risks for refugees and volunteers and the risk of exploiting refugees due to unequal power relations (e.g. project on immigration). Other projects discuss risks related to their for-profit organizational form: the solution might cause the same effects that the idea is intended to solve, the students might stop their studies and start work instead (e.g. project on unemployed students) or the project providing food coupons to homeless people might create a black market (e.g. project on food to homeless people). Other risks related to voluntarism as explained by the students were that Western people do voluntary work without much concern for the local community’s genuine needs (e.g. project on education of children in India). These latter issues are related more to the students’ need to reflect on the more problematic consequences and challenges of their idea and working process, and not only if the idea would be successful from a profit and market perspective. These reflections are also related to the social learning source (Rae, 1999) since the students need to discuss these matters with each other. But they are also related to an active learning source (Rae, 1999) since they investigated practical issues and the risk of unintended consequences when conducting interviews with potential users of their idea.

Students’ evaluations of course outcome

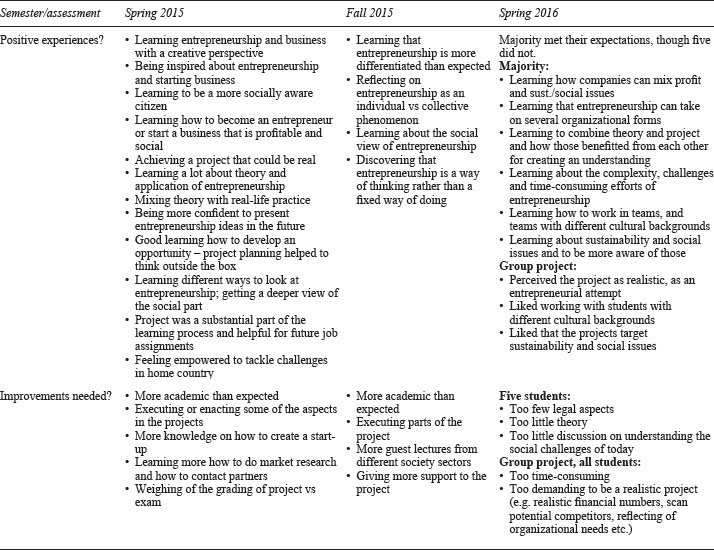

Over the years we have collected the students’ evaluations of the course outcome. However, in the first two semesters we let the students discuss and review the course together in class. Even though the students did discuss both positive and negative experiences (in need of improvement) of the course, not all students were involved, so we decided to do this exercise in written form in subsequent semesters. In spring 2015 for the first time we asked all the students to write down their perceptions regarding the course outcome. Before they replied, they also received a short update on the expectations they stated on the first day of the course. All the students’ replies are summarized in Table 2.3, in which we present both input on positive experiences and necessary improvements.

Table 2.3 An overview of students’ assessment of the course across three semesters.

In the spring of 2016 we also used an additional survey that is general and mandatory for all the courses given at the institution. Slightly less than half of the class responded. The survey asked the students to rate the extent to which they had learned the stated skills in the course on a scale between 1 (to a very small extent) and 5 (very high). The first question asked if the students had acquired the knowledge and understanding to “Identify, describe and explain forms of entrepreneurship in relation to contexts and societal change”. Over 70 per cent of the students rated this 4 and 5, suggesting that they perceived they had learned this very well or well. We also asked the students to assess their knowledge and understanding regarding to “Recognize different entrepreneurial contexts”. We received similar results there: 72 per cent estimated that they had learned it very well or well during the course. Regarding skills and abilities in relation to “apply perspectives from management and organizational theories”, over 60 per cent estimated that they learned it very well or well. Also, over 60 per cent estimated that they learned “to identify entrepreneurial challenges and suggest solutions” very well or well, and over 60 per cent estimated that they learned the “ability to plan and execute an entrepreneurial project” very well or well. Finally, we also asked the students to rate their assessment regarding the learning outcome of judgement and approach as how well the course has taught them “to critically analyze and evaluate different forms of entrepreneurship in relation to context”. This time, 72 per cent of the students assessed they were doing very well or well in this matter. In spring 2016 we could follow how the previously expressed frustration with regard to the project seemed to take a different turn, at least for some of the students. Since a majority of the respondents were positive to their learning outcomes we are inclined to believe that they had accepted our intent to combine formal, active and social entrepreneurial learning sources.2

Regarding the students’ own assessment of their learning during the course, it is clear that the project does indeed give the students a sense of having experienced a realistic entrepreneurial attempt. Further, working together in teams, often with team members from different cultural backgrounds, was highlighted as a positive outcome of the project. We also found that the students reflected on how they made use of the literature to know what steps to take in the project and vice versa, and how the project activities helped the students to understand the theoretical arguments. Hence, the literature and practical activities were perceived by the students to be complementary sources to understand the theory as well as execute the project. In line with Rae’s (1999) reasoning, where it is possible to outline three sources (formal, active and social) for entrepreneurial learning, we also find that the students mention the importance of the literature and the practical struggles of formulating a social problem, as well as the team-work activities, as key contributors for their learning process. And this process, we believe, provides the students with a broader perspective and understanding of entrepreneurship.

Our own reflection of analysing the course

In our work analysing the course and systematically looking into students’ expectations and evaluations over the years, we have learned more about what kind of audiences we are trying to educate. Despite the fact that we emphasize in the course syllabus and in the introduction lecture that this is not a course in how to start your own business, we meet these expectations from the students every year. Hence, their expectations may be less influenced by the course information received prior to the course start than their own preconceptions of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education. It seems that we have some difficulties in diverting from the dominating entrepreneurship discourse, emphasizing what entrepreneurship is and how it could be taught.

So, the question we could ask ourselves is: is it possible to expect all groups and students to be reflective regarding entrepreneurship in relation to societal issues and to learn what we are aiming to teach when they have different expectations? Some students are more focused on specific skills with regard to how to start up and run a business, while others are more in the category of an analytical audience. We have experienced that all students were able to identify a societal problem to be solved but only half of them could reflect on how their own solution and organizing might contribute to other societal problems. On the other hand, after the course the students themselves seemed to be of the opinion that they had learned what we ask for in the learning goals, and stated that they now reflected more on sustainability issues and the role of entrepreneurship and different forms of entrepreneurship. We interpret this as their ability to identify and problematize the societal issue they will solve. However, having the ability to question how their own entrepreneurial solution might create new problems may be more difficult if the initial expectation is that entrepreneurship is the only solution and can only be positive (i.e. specific and broad audience) and they do not see how entrepreneurship can play a role in contributing or causing problems.

Indeed, the students do acquire skills useful for entrepreneurship, but the group project is grounded in a more traditional academic logic. They are expected to present a written report that is assessed on the basis of their ability to make a theoretical analysis based on the course literature, their critical ability to analyse and the ability to write a report in a more academic style. In addition, they need to be active in seminars and be able to organize and present the project orally with a focus on subject content rather than visual content. Of course, these can be important entrepreneurial skills, but they are also typical generic skills common in the majority of academic courses.

A further concern regarding their ability to reflect, in relation to context, might be that the group project assignment is completed during a short period of time, only 4.5 weeks. In order to be able to make a proper analysis they probably need to experience their ideas in a real setting. Now they only have time to plan “how to execute” an idea, which also makes it possible for them to analyse the use of the business canvas or reflect on whether the idea was created or discovered. Perhaps our ambition with regard to the course can only be fulfilled with another form of pedagogy and within a longer time frame, where they have the time to test their ideas in a real setting. The students are also assessed through two more assignments, a review of another group’s project and a written exam. Gartner and Vesper (1994) argue that entrepreneurship instructors have a propensity to fill a course with as much knowledge and experience as possible and that there is a limit to how much material and how many experiences can be absorbed in a given amount of time. That might be true in this case as well.

Conclusion

We argue that it is important to encourage the students to reflect on entrepreneurship regardless of whether it is conventional entrepreneurship or societal entrepreneurship that are considered in some regards as the “good forms” of entrepreneurship, e.g. social, societal, cultural and ecological. To conclude, we do believe in the main idea of the course since we see that many of our students do manage to take the time to reflect over entrepreneurship and its role in society.

To reach an understanding about, through and for entrepreneurship we have organized our course using different sources for learning as also argued by Rae (1999). By combining the process of reading and acting entrepreneurially collectively we can see a varying degree of a sense of achievement on the part of the students. Some are very enthusiastic and even feel empowered to take on societal challenges through entrepreneurship, whereas others still feel a sense of frustration with the course, perceiving it to be too academic. According to Rae (2000), entrepreneurial learning is a process where knowing, acting and making sense are interconnected. Part of such a process is then to construct stories of “who they want to be” (p. 151). Hence, besides being experience-based, the entrepreneurial learning process is also a future-oriented thinking process. With that said, time is an important factor for us when assessing entrepreneurial learning, and a next step of interest would therefore be to follow up on our early students. What learning appears, if any? What do they take from the course into their present work life? Is there a change in learning experience compared to the initial assessment of the course?

Getting answers to those questions might give us an idea of whether it is possible to teach about, through and for entrepreneurship in a more reflective manner. It is our hope that presenting several stories of entrepreneurship, including bright and dark sides, gives the students more informed ways and opportunities of constructing “who they want to be”.

Notes

1 Authors are presented in an alphabetical order and have contributed equally to the text.

2 If, on the other hand, we are critical of this form of evaluation, it does not really tell us anything about how well the students have learned the outcomes, since we already evaluate that through their examinations.

References

Berglund, K. (2014). Entrepreneur/ship … Part 1. Course lecture: Entrepreneurship in societal change, Stockholm Business School, Stockholm University, 20 February 2014.

Berglund, K., Johannisson, B. & Schwartz, B. (2012). Societal entrepreneurship: Positioning, penetrating, promoting. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Berglund, K. & Schwartz, B. (2013). Holding on to the anomaly of social entrepreneurship: Dilemmas in starting up and running a fair-trade enterprise. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 237–255.

Edwards, L.J. & Muir, W.J. (2005). Promoting entrepreneurship at the University of Glamorgan through formal and informal learning. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 22(4), 613–626.

Fiet, J.O. (2000). The pedagogical side of entrepreneurship theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 101–117.

Gartner, W.B. & Vesper, K.H. (1994). Experiments in entrepreneurship education: successes and failures. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 179–187.

Gorman, G., Hanlon, D. & King, W. (1997). Some research perspectives on entrepreneurship education, enterprise education and education for small business management: a ten-year literature review. International Small Business Journal, 15(3), 56–77.

Henry, C., Hill, F. & Leitch, C. (2005). Entrepreneurship education and training: can entrepreneurship be taught? Part I. Education + Training, 47(2), 98–111.

Jamieson, I. (1984). Schools and enterprise. In A.G. Watts & P. Moran (Eds), Education for Enterprise (pp. 19–27). Cambridge: CRAC, Ballinger.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Nielsen, S.L., Klyver, K., Rostgaard, M. & Bager, T. (2012). Entrepreneurship in theory and practice: Paradoxes in play. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rae, D. (1999). The entrepreneurial spirit. Dublin: Blackhall.

Rae, D. (2000). Understanding entrepreneurial learning: a question of how? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 6(3), 145–159.

Smith, B.R., Knapp, J., Barr, T., Stevens, C.E. & Cannatelli, B.L. (2010). Social enterprises and the timing of conception: Organizational identity tension, management, and marketing. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 22(2), 108.

Söderbaum, P. (2000). Business companies, institutional change, and ecological sustainability. Journal of Economic Issues, 34(2), 435–443.

Söderbaum, P. (2009). Making actors, paradigms and ideologies visible in governance for sustainability. Sustainable Development, 17, 70–81.

Tedmanson, D., Verduijn, K., Essers, C. & Gartner, B. (2012). Critical perspectives of entrepreneurship research. Organization, 19(5), 531–541.