4 From entrepreneurship to entrepreneuring

Transforming healthcare education

Hanna Jansson, Madelen Lek and Cormac McGrath

For some, entrepreneurs are inventors or champions of technology, whose new ideas transform the world in radical ways, and entrepreneurship education (EE) is a way of promoting and stimulating the qualities those individuals have. This view of entrepreneurship is one we have encountered many times in our teaching practice, where entrepreneurship is often synonymous with starting a business. For others, EE falls under a broader definition of entrepreneurship and does not necessarily focus on starting a new business but is an activity focused on creativity and the development of one’s own practice. This view resonates more with our own view of entrepreneurship and is in focus in this chapter, where we share how we endeavour to integrate a broad view of entrepreneurship and healthcare entrepreneuring in a course on service innovation within healthcare.

In our context, a world-leading research-intensive medical university, EE is a practice faced primarily with two challenges. One challenge lies in establishing entrepreneurship and EE as valid parts of the different educational programmes within the university so that EE, too may be considered a key value for healthcare professionals. The second challenge is brought about by establishing a pluralistic notion of entrepreneurship that does not sell the grand narrative of modernity, or the narrative of raw capitalism, but has to find a middle ground that is multifaceted and nuanced. In this chapter we describe how we go about developing a robust and inclusive notion of EE that challenges some of the traditional notions of healthcare education through adopting a critical approach to the concept of entrepreneurship. To this end, we introduce Bourdieu’s concept of habitus as a sensitizing device, which we believe enables us to become aware of and question some of the prejudices that exist around the notion of entrepreneurship in healthcare contexts. Furthermore, we use principles of design thinking to describe how we design a course, Idea to Service Business – Transforming Healthcare (I2S), which aims to promote a critical approach to entrepreneurship in the medical and healthcare education context. In this chapter we also introduce the concept of “healthcare entrepreneuring” as a way of capturing the aforementioned critical approach.

Setting the stage

The scene for this chapter is a medical university that offers a wide range of medical and healthcare education programmes, most of which lead to a professional qualification such as medical doctors and nurses. The close connection to healthcare contexts could ideally promote entrepreneurship as a means to bring value from research to patients. As a case in point, the university has a long tradition of significant innovations, such as the pacemaker, the gamma knife and recent innovations in point-of-care diagnostics (Karolinska Institutet, 2013). These innovations have in common that they are highly technological inventions, which can be developed and sold under patent protection. Even though research has benefitted from the close connection to healthcare, innovation and education have traditionally been kept apart and the potential of connecting these two has not been fully realized. In part, this is because healthcare education is not typically driven towards the development of innovations or services and products. For example, most researchers at a medical university do not work on projects leading to the development of highly technological products that can be patented, and most students are not trained in entrepreneurship.

Since 1998, Karolinska Institutet (KI) has been part of the Stockholm School of Entrepreneurship (SSES), a collaborative effort between KI, the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm University and the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design (Konstfack). Through SSES, students at the member schools are offered courses focusing on different aspects of entrepreneurship. Each school contributes with their core focus, some with more traditional EE including management and business methods and knowledge and some, like KI, with a particular context – healthcare – and the particular rules that apply there. Still, most programmes at KI do not include entrepreneurship courses from SSES in their programme syllabus and we perceive the reason for this to be that the traditional healthcare programmes at KI are not ready for or maybe even susceptible to the traditional notions of entrepreneurship. Our experience suggests that students and researchers in the medical and healthcare context generally identify more with healthcare and the patient perspective than with for-profit life science industry and drug development. However, everyday and mundane practices in healthcare involve both learning and sense making, which Johannisson (2011) views as integral to entrepreneuring. The ability to learn and make sense in order to adjust some practices is continuously pressing in the Swedish healthcare sector, which during the last decade has been exposed to privatization and public retrenchment. We thus realized that in order to bring out the full potential of entrepreneurship and to reach the students and researchers in the medical context we needed a new and more specific focus for our courses and introduced healthcare entrepreneuring as a way of emphasizing the processual nature of entrepreneurship.

Habitus

We identified a need to define, deconstruct and redefine what is meant by EE and the entrepreneur in the context of medical and healthcare professional education (Gartner, 1990). Previous research has suggested that there are different, potentially incommensurable discourses within EE (da Costa & Silva Saraiva, 2012; Kenny & Scriver, 2012). Entrepreneurship is often described in idealized or demonized forms. On the one hand, the idealized entrepreneur is depicted and promoted in policy documents at campus, national and transnational policy levels. One such example is the Bologna agreement, which stipulates that entrepreneurship is a European value that should be sought after and implemented in higher education. This understanding of entrepreneurship, with its focus on innovation and unbounded creativity, is somewhat naïve, and represents a grand and perhaps neo-liberal narrative of modernity (Berglund & Johansson, 2007); it may be too broad and lacking in substance. On the other hand, the demonized entrepreneurship is reduced to a greedy person interested simply in making money, which in our case is in the context of state-subsidized healthcare systems. Entrepreneurship is reduced to a form of raw capitalism, where moneymaking endeavours stand above other values such as the duty of caring for patients, ethics etc. Our experience suggests that this view of entrepreneurship as something bad is particularly pervasive in the medical and healthcare profession context. However, it may be a specific Swedish or Scandinavian perspective, due to the fact that healthcare is state-subsided in Sweden and there is a willingness to pay a high level of taxes for healthcare services for the broader population (Eckerlund, Johannesson, Johansson, Tambour & Zethraeus, 1995).

Traditionally, MDs and other healthcare professionals are socialized into a profession that cherishes values such as safety, competency and proficiency (Jaye & Egan, 2006). Medical and healthcare curricula are designed to promote these values, and little attention is dedicated to different forms of entrepreneurship today. In this chapter, we use Bourdieu’s concept of habitus as a sensitizing device to delineate the types of challenges that are expressed through different assumptions and prejudices that keep new and emerging concepts and disciplines such as EE outside the curricula. Habitus focuses on ways of acting, feeling, thinking and being. It emphasizes how history is an integral part of human identity. Furthermore, habitus defines, indirectly, not only the choices people make but also how people may subsequently act. Habitus is acquired through a process of acculturation into certain social groups such as social classes or our peer groups, and also the working place. In terms of the healthcare system where many of the students will finally work, it may be the case that entrepreneurship has never been a part of the collective identity, or a part of the joint enterprise. Habitus, as a sociological concept, is as much about explaining the structure of the social world as about explaining the mechanism that ensures its transformation, and also the reproduction of behaviour (Reay, 2004) or, as Bourdieu writes,

Habitus is a kind of transforming machine that leads us to “reproduce” the social conditions of our own production, but in a relatively unpredictable way, in such a way that one cannot move simply and mechanically from knowledge of the conditions of production to knowledge of the products.

(Reay, 2004)

Normally, one may not be consciously aware of habitus in our everyday environment, as it is essentially never articulated explicitly; instead, it is part of the fibre of the everyday experience. Habitus becomes evident first in the context of an alien or new environment. According to Mutch (2003), habitus allows one to identify an explicit link between patterns of thought and social conditions. Consequently, the particular forms of habitus are formed in specific social conditions and become part of the fabric of those social conditions. Thus, habitus is not necessarily a set of rules and principles, but rather the embodiment of rules and principles, which are defined socially by inhabitants in different fields. It is this embodiment of assumptions and expectations that we choose to target in the I2S course.

Habitus must be viewed in relation to Bourdieu’s other concepts: capital and field (Brosnan, 2010). Academia is itself a field and within academia, medical and healthcare schools may also be viewed as fields, with different disciplines, cultures etc. (Albert, Hodges & Regehr, 2007). In each field, different notions compete for access and acceptance. Students bring with them different forms of capital – cultural, economic, social and symbolic capital – but the field itself also has a capital and a set of rules that are articulated tacitly. Power within a field or discipline is culturally and symbolically created. Furthermore, it is maintained through the interplay of agency and structure (Brosnan, 2010). The main way this happens is through socialized norms or tendencies that guide behaviour and thinking (Wacqyabtm, 2005). Thus, in order for EE to make an impact and establish itself as a legitimate aspect of healthcare education, social and political agency must be questioned. The activities outlined in this text are a part of questioning the field of medical and healthcare education as a way of addressing the two main challenges outlined above: (i) putting entrepreneurship on the agenda for medical and healthcare education and (ii) promoting a pluralistic and nuanced notion of entrepreneurship.

Design thinking

When looking for a new approach to promote a multifaceted notion of EE, going beyond research-based highly technological product development, problem-solving methods inspired by the work of designers caught our interest. Design thinking (DT) is a method for innovation that puts the user needs in focus. Unlike other problem-solving methods, where the solution is typically in focus, DT concentrates on the challenge or problem. The problems addressed are often so-called “wicked”, open-ended and difficult to solve problems, such as societal and health-related challenges. DT is described as:

A methodology that imbues the full spectrum of innovation activities within a human-centred design ethos. By this I mean that innovation is powered by a thorough understanding, through direct observation, of what people want and need in their lives and what they like or dislike about the way particular products are made, packaged, marketed, sold, and supported.

(Brown, 2008)

DT is focused on the early stages of innovation and involves practical work with personas, prototyping and role play while working in an iterative way, alternating between problem and solution (Carlgren, 2013).

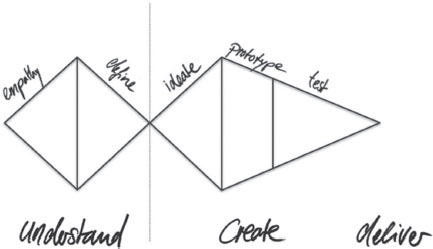

The double diamond metaphor is a way to describe the process (Design Council, 2005). It consists of four different phases: (i) discover a challenge, (ii) define specific needs, (iii) develop ideas and (iv) deliver solutions. The double diamond is used to illustrate how the design process is either diverging or converging. At the beginning of the process, one expands the perspective to discover all the possible angles to the challenge at hand, before narrowing down the perspective and defining specific needs (insights, what needs to be done) to continue working. When the second diamond begins, the perspective is again diverging when as many diverse ideas as possible are developed. To be able to deliver a final solution, the perspective needs to be narrowed down, going for only one or two solutions. A slightly modified version also incorporates the DT steps as described by the “d.school”, the Institute of Design at Stanford University (d.school, 2009). In this model, the second diamond covers three steps; ideation, prototyping and testing. Here we emphasize an iterative approach of DT (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Schematic illustration of the double diamond process map of DT.

Source: Cecilie Hilmer, co-course director 2016.

A twofold approach

This chapter presents the design and development of the course I2S where the concept of healthcare entrepreneuring is intended to signal the transformative focus of our critical approach to entrepreneurship and EE. Further, the concept is used to identify the processual and lived experience of entrepreneuring as something that is enacted on a daily basis as opposed to something that is done to an organization or individual (Johannisson, 2011). The verb form entrepreneuring signals the active involvement of students in creating knowledge and an awareness of the active development of ongoing practices but also lends itself as an invaluable theoretical concept for professionals in healthcare contexts that does not always lends itself to predictability and pre-existent goals (Steyaert, 2007). Consequently, healthcare entrepreneuring is characterized by students working with creative tools and methods to transform (i) a shift in their thinking around what it means to study at a medical university and (ii) the shift in practice that is brought about by the newly found focus on services and development of one’s own practice. I2S is designed to look beyond the biomedical industry, represented by big pharma and bioand med-tech companies that focus on intellectual property and patents. The objective is to explore different ways to improve healthcare, and this idea of improvement is a core concept throughout the course. We aim to get the students to understand, from day one, why healthcare improvements are needed and how the healthcare context is different from other types of organizations, and further and perhaps most importantly we wish for them to see the opportunities to engage in entrepreneuring as an everyday activity (Johannisson, 2011). We believe that this may be experienced by the students as taking a step away from the expected trajectory many healthcare students have (Jaye & Egan, 2006).

The overall aim with I2S was to develop a course that (i) is based on a broad and inclusive definition of entrepreneurship, challenging the traditional perception of entrepreneurship in the given context, and (ii) reaches out to other students than those who want to start up a business or work within the life sciences. The purpose is to lay the foundation for creativity, innovation and action, aiming to broaden the perspectives of innovation and entrepreneurship and the students’ future occupations.

Idea to service business – transforming healthcare

The I2S course was developed at KI and the Unit for Bioentrepreneurship, with the aim of introducing students to the concept of service innovation and development of one’s own practice within the healthcare sector. The objectives are to (i) introduce students to the context of healthcare from a service innovation perspective, (ii) provide effective design tools and basic entrepreneurial tools, and (iii) to broaden their perspective on career alternatives (industrial, private etc.). The course is a 7.5-ECTS course at master’s level, and was offered for the first time in 2010. For the course to be interdisciplinary, it has been taught in collaboration with SSES since 2013 with students from all five member schools.

The course is conducted as part-time study, two evenings per week over a period of two months. Theoretical lectures are provided in combination with practical work, inspirational talks and individual literature studies, for each learning objective. Most evenings are divided into two sections: a theoretical part, covering specific concepts such as service design and project planning, and an interactive part, where the students experiment and gain practical experience. Some sessions focus on the translation of concepts whereby invited guests share personal stories from working in the field. The core focus of the course is not to give the students knowledge and experience about a specific method or theory. Instead, the focus is to create and work with opportunities specific to the healthcare sector. To guide the students through the process of service innovation, design and entrepreneurial tools are provided. The course will now be described following the DT process: (i) understand, (ii) create and (iii) deliver – three critical steps taking us from entrepreneurship to entrepreneuring – when transforming healthcare education.

Understand – knowing, unknowing and knowing again

The first step is to explore the present situation, in this case the course and service innovation within healthcare. Following a brief introduction to the course aims and learning objectives, the students elaborate on their preconceptions of concepts and expectations of the course in group discussions. What is their understanding of entrepreneurship, service innovation and the different practices within healthcare? What do they know about healthcare and life science? What prior experiences do they bring with them and what do they expect to learn? The final list of expectations is linked to the introduction of the course format and content. To get a head start in practice, the first evening ends with a guest sharing her/his own experience of starting up a service-based project or company within healthcare. The students are encouraged to critically reflect on the story and consider their own experience in relation to the experience of the invited guest.

Many students come to the course with a traditional view on entrepreneurship, that it is about starting up high tech companies and earning as much money as possible. Even though these students have applied to a course about service innovation within healthcare, many choose a picture of money or a man in tie and suitcase when asked to illustrate entrepreneurship. By introducing the first step, the students become more aware and “embrace” a broader definition of entrepreneurship. Likewise, their understanding of healthcare contexts and practices develops, going beyond trauma situations in the casualty department commonly depicted in TV series and the media to more commonplace events like a nurse instructing a patient on how to administer their medicine.

Defining the scope of the course is part of the first step. Emphasis is put on group formation and collective decisions have to be taken. What should the focus for the group work be? How do we collaborate and communicate in teams? To guide the students, there is an introduction to what a project is and, since the course targets students other than healthcare professionals, we talk about interdisciplinary teams. What is it like to work in a multidisciplinary group? What is the difference between interprofessional and intraprofessional work settings and practice? The students get the tools to put together a simple group contract, and all groups have to choose a group leader. The student’s hand in a short written proposal, outlining the challenge they want to work on (and base their idea on). The proposal includes a short description of the need, why they want to study this and how they will proceed with the actual work (see Table 4.1 for an example of the group project).

Table 4.1 Group project example – understand

| The first step for the team in the course project is deciding on a challenge to work with. This is an important step as all team members share their interests and perspectives. The first decision has to be taken together as the team members are still getting to know one another. One team chose the challenge of ensuring emotional wellbeing in elderly homes, with the difficulty of the elderly not being able to express their needs strongly enough and the lack of time of the staff to engage with the patients to identify problems early enough to prevent an effect on their health. The team especially focused on the caregivers’ experience and were able to accompany a nurse during her work at an elderly nursing home and while she was interacting with elderly patients. As a result of the observations and interviews the team identified one root problem that they wanted to work on further: The “handover” from one nurse to the other. Given the high workload of the staff in the home, they discovered that it was frustrating for them not to be able to perform their duties of observing patients for signs of concern and properly maintain records of patient’s activities, incidents and behaviours. The high amount of paperwork to be done at the end of a shift worsened this situation. |

Source: Cecilie Hilmer, co-course director 2016.

At the beginning of the course, some students question the time spent on group formation and project start-up. They argue that they have worked on projects in teams before and want to get started on the “real content”. Later on, however, most of them come to value the importance of project planning, and of getting a common understanding of the project aim, idea and work. Furthermore, there are always some students who question why the groups are formed based on interdisciplinarity, to get as diverse groups as possible, but later on almost all students highlight the interdisciplinary work as one of their most important lessons learned. We believe that this increased critical awareness occurs partly because the course design evokes elements of community-building in that the students engage with each other around the group project. However, for most students the project is something entirely new; it forces them to let go of their expectations and encourages them to work in new ways, which may run contrary to previous experiences.

I have actually had a lot of use of the new ways to look at things e.g. the “turning everything inside out and upside down” in my daily work and it has already improved the projects I am working on.

Having a 6-year working experience in hospitals and diagnostic centres as biomedical analyst I now see a different approach of how problems in the healthcare sector can be solved. Innovative ideas coming from people with different backgrounds seem to be the answer.

(Anonymous students, 2015)

Create – develop, test and evolve

A central method within service design is prototyping, “anything tangible that lets us explore an idea, evaluate it and push it forward” (Brown, 2008). Prototyping is something completely new for most students, and the course takes them through many practical examples and two full sessions that are devoted to the prototyping and testing of ideas (Table 4.2). In the first session we introduce the concept of prototyping, what it is, why it is important for service innovation and how you do it. The students discuss what they want to test, how to include the user perspective and which interaction points are crucial for the user. They end up formulating critical questions to be addressed. In the second session, the students test their prototypes in a “prototyping market” engaging in role play while acting as each other’s users (Figure 4.2).

Table 4.2 Group project example – create

| Based upon the previous work the teams have developed one or more potential solutions to the described/identified problem. Most of the time these solutions only exist in the minds of the students. This is one of the most challenging phases of the process, as the idea will have to be brought to life in order to test whether it really meets the identified needs. This is particularly challenging due to the nature of healthcare, where solutions will very likely be service based. The previously described team from the course in 2016 decided to focus on the “handover” between shifts, and developed a tool that simplifies the administrational work and includes the possibility to add other forms of information beyond facts that need direct follow up, making the tool work like a diary where information can be included during the shift and shared according to need. A “Wizard of Oz prototype” was build out of cardboard [Figure 4.2], where one team member made sure the testee saw the right interface at the right time. Other team members acted out the roles of the patient and the nurse of the following shift. One team member acted as a pure observer, took notes on the testee and his/her actions. After each test, the complete team would take some time to interview the testees about their experience. |

Source: Cecilie Hilmer, co-course director 2016.

At the beginning of the prototyping sessions, it is not uncommon that the creative methods and exercises are questioned. Many students think that they are simple and rudimentary. Furthermore, the students almost always start brainstorming without further direction, coming up with ideas for how to solve the problem. This is something that we see from year to year, and it is most common among the students with a natural science background. Another important part of the second step is the role play, where the students have to test their prototypes when acting as each other’s users. This is not easy for the students, and the teachers need to remind them that they should test each other’s prototypes and give each other feedback from the tentative user perspective. They should critically question their own experience as users and should not evaluate each other’s ideas based on entrepreneurial tools and previous knowledge. After completion of the course’s second step, the students have often embraced the user-centred way of working. They see the value of the creative methods when exploring the present situation for the user, or patients within health innovation, and reveal all possible challenges before going into the creation of ideas to solve the problem.

Figure 4.2 Preparing for role play, testing of prototypes and collecting user feedback.

Source: photo by Cecilie Hilmer, co-course director 2016.

Deliver – disseminate and reflect

The third and last step is to deliver the final project reports and presentations. The different service ideas (Table 4.3) are presented orally as a short speech, or “pitch”, to the whole class and a panel of teachers and professionals in the field. This is followed by a general discussion. The focus of the pitch is to communicate the need the group have analysed and the functionality of the service they have developed. They are expected to present their service with the help of visualizations such as prototypes, movies, illustrations and images. Each group acts as critical reviewers for another group, reading the process report of the other group as well as preparing and asking questions and giving feedback after the presentation.

Table 4.3 Group project example – deliver

| At this point the teams have ideally gone through two iterations or more, meaning rounds of testing and improving their proposed solution, or even changing the solution completely, if the feedback showed that the prototype did not meet the user’s needs. The presentation takes place in the form of a pitch but with background about the users and their needs. It is important to understand which insights lead the team towards this specific service product. The final feedback from the opposition, course teachers and guests helps the teams to improve the project report that they will hand in a few days later. We decided on having the pitches without a digital presentation and we wanted to see all members involved in some way. The only digital tool allowed was video material. Also, this was an interesting experience for the teams as it required more arrangement and practice within the teams. We were able to create a safe space in the classroom to allow this experimental atmosphere and had teams presenting with a variety of approaches, mixing role play, storytelling, self-made props out of cardboard, and showing videos. The students enjoyed it. The aforementioned team presented their solution as software on tablets that enables the healthcare staff to enter specific information, especially concerning the wellbeing of the patients. It combines this with the usual administrative documentation tasks, reducing the paperwork needed by adding simpler language and more icons and including the patients themselves as points of input. In their case, more testing in the real setting, the elderly nursing home, would be the ideal next step. |

Source: Cecilie Hilmer, co-course director 2016.

The group project is summarized in a process report, where the students describe in five chapters how they have developed their service step by step. These chapters explore and describe: (i) the initial challenge that they set out to solve, (ii) the intended user, (iii) prototyping and testing, (iv) the application of entrepreneurial tools and (v) future possible steps to further develop the service idea. The practical work is also summarized in a written individual reflection on their experience and learning. The reflection should revolve around the work process itself and one’s personal contribution to the project. The team dynamics, including one’s personal role in the team (the position one took, what felt good, what went wrong and what one would do differently next time) are also discussed, as is their critical understanding of the field of “service innovation within healthcare” and its relation/relevance to the students studies/work. The students are asked to describe what they have learned during the course and use their prior experiences to situate the course in a wider context.

The group project is assessed by capturing the entrepreneuring, not the end result. The group process is described and discussed vis-à-vis three levels of understanding, where the students (i) show understanding for the process (the different steps, etc.), (ii) apply methods and theories and (iii) reflect on their experience and learning (the process, individual contribution, the team and the context). This approach enables the students to review and critically reflect on their own process as well as their own assumptions and values that they brought with them into the project. On completion of the third step, the students have developed a more critical awareness of entrepreneurship within healthcare. Even though the focus for the group project was to design and develop a service idea, the opportunity of transforming healthcare through means other than a start-up become more evident and is an idea that the students bring with them in their future profession.

Towards an entrepreneuring self

In working with the I2S course we have come to view habitus as an important concept, forcing us to rethink and reappraise, and together with the students engage in critical self-reflection about what it means to be a healthcare professional, what innovation and entrepreneurship is and how entrepreneuring can be a natural part of healthcare professionals’ education and practice. As such, habitus is two-dimensional, forcing us as teachers and course and programme leaders to rethink the concepts and nomenclature we use in the course, framing development in terms of services and not solely in terms of products, and, perhaps even more importantly, by critically reviewing the notion of the entrepreneur as someone who accomplishes heroic acts and instead evoking the notion of the healthcare entrepreneuring and the entrepreneuring self as a facet of every healthcare worker’s daily practices (Berglund & Johansson, 2007; Steyaert, 2007; Johannisson, 2011). Furthermore, using the concept of habitus as a sensitizing device encourages us to consider students’ assumptions and expectations of engaging in entrepreneuring in the context of medical and life science education. The use of DT when designing the course has meant that the students encounter uncertainty and need to take responsibility for their own learning. This uncertainty is revealed, as they are required to identify innovations and changes in relation to their practices, which may run contrary to the traditional knowledge acquisition, and socialization processes they may be accustomed to. In other words, it situates the students in unknown territory. As this is new for many students, we need to talk about it throughout the course. Our focus is on targeting the symbolic capital inherent in the way medical and healthcare education is taught to students today, and also to promote critical reflection on the socialization process (Brosnan, 2010; Witman, Smid, Meurs & Willems, 2011). By asking the students to question their own expectations we create opportunities for them to critically reflect on their previous thoughts and assumptions on entrepreneurship. Our experience is that, most of the time, the students initially hold a more traditional view of entrepreneurship and see the entrepreneur as a superhero but this typically changes during the course, which is evident in their reflective assignment. Questioning this preconception is a way that allows us to tackle the second challenge outlined above, developing a pluralistic view of EE, not only corresponding to the traditional view of the entrepreneur as starting a new for-profit business but also acknowledging other forms of entrepreneurship(s). The course aims to teach the students about many different topics and disciplines, from identifying needs to designing and testing solutions and packaging the proposed solution as a service idea. Ideally the course will also empower the students to view entrepreneuring as part of the practice of healthcare in their future occupations. The students research in depth the topics that they need to know more about and/or find especially interesting. At the same time, they learn from and with each other in their interdisciplinary teams by sharing knowledge and experiences from their own discipline, which enables them to work on “bigger” problems than those they would be able to tackle on their own (Ledford, 2015). This is essential in the process of healthcare entrepreneuring.

Each year we find that the non-business students gain the most from handson supervision from teachers and peers as regards how to develop the entrepreneuring self.

The most rewarding thing about working in a group was to be able to benefit from the combined knowledge of all my group members. Being a KI student I was glad to be able to contribute with my own knowledge (thinking a lot about the elderly people and how they can use our service in an easy way). The course made me see areas in the healthcare that need development, and hopefully I might come up with ideas that produce improvements. As a healthcare professional, I will have many patients every day, and with new ideas about for example journal writing and queuing systems we might be able to work more effectively and help more people.

(Anonymous student, 2015)

The business students gain most from the different cases that illustrate the healthcare perspective of business, with its context-specific challenges and opportunities.

To be honest, during the course I was sometimes frustrated that I was not learning anything new about business. However, now that I reflect back on the course I realize I have learned a tremendous amount of new things that at first are seemingly unrelated to business but, when I come to think of it, are very much business, and what’s more, they open up new doors to my understanding of business.

(Anonymous student, 2014)

So what comes out of all this, what have students embraced and what have we as educators learned? With the I2S course, we aimed for a course that was based on the broad definition of entrepreneurship, which reaches students from basic study programmes and where healthcare entrepreneuring is brought into focus. Through the new focus on services (in contrast to highly technological, tangible, often patented products) and the specific focus on challenges and opportunities within healthcare (in contrast to commercialization of research results, and drug development within the healthcare industry), the course takes a broader view of entrepreneurship in the medical context into account. In the process reports we see repeated examples of how the students have embraced the medical context when presenting the process of developing service ideas, often packaged as social ventures. By using these foci, we find that more and more of the basic study programmes leading to a professional qualification offer the I2S course as an elective programme for their students. With the foundation in DT the course captures the essence of healthcare entrepreneuring, having the students work and focus on process and not merely the end product. In the individual reflections, we see examples of how the students link their new knowledge to their ongoing studies and to their future careers.

Furthermore, during the development of this course the importance of co-development has been evident to us as educators. The course idea was initially developed with a student who questioned the technical product-oriented focus of existing courses. The student wanted a course with a more general approach to the packaging of knowledge, methods and processes generating products such as consultancy services, websites, applications etc. In collaboration with this “user”, we decided to develop a course about service ideas. As already described, we used the concept of DT to capture the essence of service innovation. Again we co-developed the content with a designer to fully be able to fully embrace the design thinking process, and after two years a designer was recruited as the co-course leader. We find that the work on this course has increased our understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of working with interdisciplinary courses. We have discovered that laying the foundation for the group work is very important. We have also seen that early communication is key. Most important however is the transition and a shift in focus from entrepreneurship to entrepreneuring as something always happening, a state of being (Johannisson, 2011). A course like this needs to continually improve and develop, and the next step in this journey would be to incorporate new learning outcomes and examinations that explicitly emphasize critical aspects of entrepreneurship. We like to think that we practise what we preach and that in each iteration of the course we ourselves are healthcare entrepreneuring.

In conclusion, we view ourselves as brokers of change (McGrath & Bolander Laksov, 2014), and acknowledge that it is important when discussing healthcare entrepreneuring with students we do it in a way that students are forced to question their own assumptions and perceptions about what it means to engage in entrepreneuring in the healthcare context. At the same time, we can see how our brokering role works in at least two different ways; in the SSES context we are able to question the strong business-oriented discourse and in the healthcare context we introduce and encourage the idea of healthcare entrepreneuring which has been outlined above. EE is still treated as a peripheral subject in relation to the other subjects at our university. Emphasizing healthcare entrepreneuring instead of entrepreneurship may be a way of tackling the challenges we addressed in the introduction to the chapter. Consequently, a pluralistic and nuanced conceptualization of EE could also mean that the concept of healthcare entrepreneuring permeates the medical and healthcare programmes. Although we are still on the periphery in the medical and life science university, we feel that the different aspects of how we work outlined in this chapter demonstrate some of our efforts at moving in from the periphery, and we feel confident that we are moving in the right direction.

References

Albert, M., Hodges, B. & Regehr, G. (2007). Research in medical education: Balancing service and science. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 12(1), 103–115.

Berglund, K. & Johansson, A.W. (2007). Constructions of entrepreneurship: a discourse analysis of academic publications. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 1(1), 77–102.

Brosnan, C. (2010). Making sense of differences between medical schools through Bourdieu’s concept of “field.” Medical Education, 44(7), 645–652.

Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92.

Carlgren, L. (2013). Design thinking as an enabler of innovation: Exploring the concept and its relation to building innovation capabilities. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology.

D.school. (2009). Steps in a design thinking process. Retrieved from https://dschool.stanford.edu/groups/k12/wiki/17cff/.

da Costa, A.D.S.M. & Silva Saraiva, L.A. (2012). Hegemonic discourses on entrepreneurship as an ideological mechanism for the reproduction of capital. Organization, 19(5), 587–614.

Design Council. (2005). Design Council. Retrieved from www.designcouncil.org.uk.

Eckerlund, I., Johannesson, M., Johansson, P.O., Tambour, M. & Zethraeus, N. (1995). Value for money? A contingent valuation study of the optimal size of the Swedish health care budget. Health Policy, 34(2), 135–143.

Gartner, W.B. (1990). What are we talking about when we talk about entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 5(1), 15–28.

Jaye, C. & Egan, T. (2006). Communities of clinical practice: implications for health professional education. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 8, 2.

Johannisson, B. (2011). Towards a practice theory of entrepreneuring. Small Business Economics. 36(2), 135–150.

Karolinska Institutet. (2013). Important discoveries made at KI. Retrieved from http://ki.se/en/about/important-discoveries-made-at-ki.

Kenny, K. & Scriver, S. (2012). Dangerously empty? Hegemony and the construction of the Irish entrepreneur. Organization, 19(5), 615–633.

Ledford, H. (2015). How to solve the world’s biggest problems. Nature, 525(7569), 308–311.

McGrath, C. & Bolander Laksov, K. (2014). Laying bare educational crosstalk: a study of discursive repertoires in the wake of educational reform. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(2), 139–149.

Mutch, A. (2003). Communities of practice and habitus: A critique. Organization Studies, 28(4), 546–563.

Reay, D. (2004). “It’s all becoming a habitus”: beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 431–444.

Steyaert, C. (2007). “Entrepreneuring” as a conceptual attractor? A review of process theories in 20 years of entrepreneurship studies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(6), 453–477.

Wacqyabtm, L. (2005). Habitus. In International Encyclopedia of Economic Sociology.

Witman, Y., Smid, G.A.C., Meurs, P.L. & Willems, D.L. (2011). Doctor in the lead: Balancing between two worlds. Organization, 18(4), 477–495.