9

Managing Your Mail and Internet Marketing Operation

HOW DO I GET MY PICTURES FROM HERE TO THERE?

The ad in the photography magazine shows a distraught woman at the airline terminal being informed by an attendant that she has missed her plane. “Don’t Let This Disaster Happen to You!” reads the caption. The full-page ad for a software company goes on to imply that if you don’t keep up with digital technology (by buying their product), you will be left hopelessly behind.

Do you sometimes get a nightmarish vision of your competition flying light-years ahead of you, enjoying high-powered electronic sales and delivery advantages with the photo buyers out there in cyberspace?

“Hey, I don’t have the expertise or the budget to keep up the pace in the digital world. How can I compete?” you say.

It’s true that fax, e-mail and the Internet have opened up new worlds of instant-speak. But what channel of communication do photo buyers really prefer?

Regular mail is great for introductions, promotion and routine communication. Digital—both for photographs and promotions—is the most common delivery method of images to editorial photo buyers.

One way doesn’t necessarily rule out the other, as the different ways have different strengths and weaknesses. Both the “good old ways” and digital can happily coexist.

Delivery: As Close As Your Mailbox and Computer

Communication by computer enjoys big-time media attention, but as stated previously, the reality is that standard U.S. mail and courier service continue to be communication methods that are still viable for editorial photo buyers. If you have a large number of slides from before you went digital, there are photo buyers who still accept slides as submissions. Would they prefer digital? Yes, but sometimes they need a very specific image and it might only exist as a transparency in your slide file, and if that is the case you can soon make a sale.

Before you shut down your computer, however, check out chapter seventeen. You’re going to find that the Internet offers an important and growing sales-and-delivery method that may one day rival the U.S. mail, and you can start getting your feet wet right now.

In 1981 Rohn Engh wrote in his newsletter, PhotoLetter, that within a decade, digital delivery of photo illustrations would be the norm. Wrong. Even many commercial stock photographers are not convinced that digital photos will completely replace film-based photography.

Having your own website is perfect for delivering information about you and your photography. If you specialize and inform Web users of your specialty, they can look at your online specialized portfolio. A phone call or e-mail from the photo buyer will get the sales process moving. Again, for more information, see chapter seventeen.

Our Postal Service—A Bargain for the Stock Photographer

As an editorial stock photographer, you can market your pictures almost entirely by mail or courier. Photo buyers like working this way. It saves them time, and it’s efficient. For you, marketing by mail is less expensive than costly personal visits. The risk? Minimal. I’d happily debunk the myth of photos missing in the mail as I have yet to come across a verifiable case of an editorial stock photographer who has lost photos when sent through the mail.

We’ve all heard horror stories about the U.S. Postal Service, but I’ve found the vast majority of those lost picture stories to be untrue. For example, at my seminars I ask people to describe their experiences with photographs lost in the mail. When the facts are laid out, I’ve yet to discover one case that could be documented. Not that it isn’t easy to have a photograph damaged or lost in the mail. Simply ship it in a flimsy envelope, and don’t identify it as yours: The odds are you’ll never see the image again.

When photos fail to arrive at their destination or fail to return home, it most frequently is the photographer’s fault, not the fault of the postal service. Typical reasons are incorrect address, incorrect editor, no editor, no ZIP code, no return address, no e-mail address, no identification on prints or slides, or poor packaging.

We sometimes get a call from a photo buyer who asks, “Can you locate the address of Harrison Jones for us? We want to send him a check, but all we have is a slide with his name on it. No address. No phone.”

Stock photo agencies and film processors must know something about the U.S. mail. They have shipped pictures across the nation and around the globe for years. Magazines use the postal service successfully, as do Light Impressions and Spiegel.

If there is a risk, it’s in not sending your pictures through the mail. Pictures gathering dust in your files are hazardous to your financial health.

Preparing Your Stock Photos for the Market

The first impression a photo buyer has of you comes from the way you package and present your material. Photo buyers assume that the care you’ve given to your packaging reflects the care you take in your picture-taking and your attentiveness to their needs. They believe they are paying you top dollar for your product. They expect you to deliver a top product. If you want first-class treatment from a photo buyer, give her first-class treatment.

SENDING TRANSPARENCIES

To best protect your transparencies, send them in vinyl sleeves. Use slides mounted in plastic or cardboard, or else unmounted. For mounted slides, use the popular vinyl pages that have twelve 21⁄4" (57mm) or twenty 35mm-size pockets on one page. For unmounted transparencies, the vinyl pages also are useful. For prints, four 4" × 5" (10cm × 13cm), two 5" × 7" (13cm × 18cm), or one 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm) can fit in one page. If you have only a few transparencies to submit, cut the page in half or quarters. Send your selection in a smaller envelope. Single acetate sleeves are another option for protecting transparencies. They’re available at photo supply houses. In the past there has been some concern as to whether the polyvinylchloride (PVC) in vinyl sleeves can damage a slide. Use this rule: Ship your slides in thick vinyl (or nonvinyl) sleeves, but store your slides in archival plastic pages. Don’t use a thin plastic page to ship your slides because the slides fall out too easily.

When you submit transparencies, you might wish to keep not only a numerical record of your submission but a visual record as well. Here are four ways: (1) Make a color photocopy (at a library, Xerox Center, bank, Kinko’s or a print shop); (2) make a 35mm black-and-white or color shot of your slides on your lightbox; (3) using a digital camera, make a low-resolution picture of each image; (4) using your scanner, copy your submission and save it in a folder entitled “Submissions sent.” Keep the results on file until your slides are returned.

How can you caption unmounted transparencies? Fit your caption information on an adhesive label, and place the label at the bottom of the protective sleeve or vinyl page pocket where it won’t cover the image.

Inexpensive protective vinyl (or similar plastic) transparency-holder pages are available from your regular camera equipment supplier and from mail-order companies. For an up-to-date listing of suppliers, check the ads in any photography magazine.

SENDING CD-ROMS

Label CD-ROMs with your name, e-mail, postal address and contact information—just like anything else you send out. Your CD label should look neat and crisp and convey professionalism.

Send CD-ROMs packed in jewel or slim-line cases, along with a cover letter. Ship in white cardboard mailers that are clean and crisp. A great source for these cardboard mailers is Mailers Company, 575 Bennett Road, Elk Grove Village, IL 60007, (800) 872-6670, www.mailersco.com.

Make it clear in your cover letter that your specialized images are going to match the photo buyer’s special-interest area. Indicate what format the images are saved in and any other details a photo buyer might need to be able to open your images. For example, is your CD-ROM cross-platform compatible? That is, will the CD-ROM work equally well in a Macintosh or a PC?

If you’ve selected a photo buyer from your Market List to send the CD-ROM to, invite the photo buyer to download your selection of low-resolution images into his database. Depending on your history of publishing with the buyer, you might suggest that you can send a selection of high-resolution images also.

SENDING BLACK-AND-WHITE PRINTS

While this should generally be avoided, sometimes it is the only way. If you have a lot of prints I really recommend that you invest in a good flatbed scanner with high enough resolution to make high-resolution digital scans of your prints. There are still some photo buyers who wish to see (paper) black-and-white prints. If your black-and-white prints are dog-eared or in need of trimming and spotting, they may miss the final cut. Often, excellent pictures never reach final layout boards because they make such a poor first impression. As the saying goes, “You never get a second chance at a first impression.” Your stock photos make the rounds of many buyers, so check your prints regularly to trim any edge splits or dog-ears. Before submitting black-and-white 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm) prints, retouch any flecks.

Use plastic sleeves to protect your black and whites. These sleeves present a fresh, professional and cared-for appearance, and they hold your prints in a convenient bundle for the editor. They come in 81⁄2" × 11" (or larger) (22cm × 28cm) sizes. One sleeve can hold up to fifteen single-weight or ten double-weight prints. A company that sells 3 mil sleeves is: Sunland Manufacturing, 1650 93rd Lane, Blaine, Minnesota 55449, (800) 790-1905.

Should you send negatives? If an editor wants your negatives, it’s probably to make better prints than those you have submitted. Rather than run the risk of damage to your negatives, volunteer to reprint the pictures or to have a custom lab print them. Avoid sending negatives to photo buyers.

IDENTIFY YOUR PRINTS, THUMBNAILS AND TRANSPARENCIES

Identify slides with labels (1⁄2" × 13⁄4" [13mm × 44mm] return address labels, such as Avery #8167, are good for this) that state your name, e-mail address, and phone number. Put the labels on the slide mount. You should use two labels for each slide mount, one for contact information and one for caption information. Caption information should also accompany your preview scans. Read more about captions in the next section.

Identify each of your black-and-white prints using a label (on the back) that includes a copyright notice and your name, address, e-mail address and telephone number. Also include your picture identification number (see chapter thirteen).

Do not include a date code in your identification system. Photo buyers will recognize the date, and your picture will be “dated” before its time. If slides have a date printed on the side, cover it with a label imprinted with your identification details. If for some reason you do need a date, put it in Roman numerals or use an alphabetical code, for example, A = 1, B = 2, C = 3 and so on. The fifth month would be E, and the year 2003 would be MMIII. E/MMIII.

CAPTIONS

Accurate captions have become an important tool for photo buyers. Since you are specialized and photograph in a specialized field, you know a lot about your field of choice. The photo buyer will rely on you to help with important information about your images. On slides, use a separate label for captions. Mark the label with an identification number and captioning information.

Try to keep captions brief yet complete. If you’re captioning a photograph of a horse grazing in a pasture, don’t caption it “horse in pasture” and leave it at that. The caption might read something like “Thoroughbred grazing in Wyoming pasture in spring.” You want to be informative, and you want to state the obvious, but also include the not so obvious.

Typically you can caption digital images in the photo-editing software that you use (Photoshop, for instance). This is attached to each image as part of the digital file. Mention this in your cover letter.

Extensive captioning of your images can benefit your marketing efforts. How? Powerful search engines maintain “Web crawlers” that seek images for display on their websites. If a photo buyer is searching for an arcane word, location or species, for example, and you have listed it in your captions, you might be more likely to get a hit and make a sale.

CHECKLIST

Before packing your photographs to send to a prospective buyer, give your images this checklist test.

- Selection.

Do your images fall within the specialized interest area of the photo buyer? - Style.

Do your photographs follow the illustrative style the buyer is partial to? - Quantity.

Are you sending enough? Generally, you should submit a minimum of two dozen and a maximum of one hundred. (There are exceptions to this, such as the single, truly spectacular shot that you might rush to an editor because of its timeliness.) - Quality.

Can your photographs compete in aesthetic and technical quality with stock photos the buyer has previously used? - Appearance.

Are your prints, digital scans and transparencies neat and professionally presented?

If your photos don’t conform to the suggestions I’ve given, then wait to submit them. Eagerness is a virtue, but as in any contest, you must match it with preparedness.

Packaging: The Key to Looking Like a Pro

Once you have your photos prepared, present them in a professional package. One editor told me that she receives about ten pounds of mail every morning. She separates it into two piles: one pile that she will tackle immediately, and a second that she will look at if and when time permits. I asked her how she determined which pile things belonged in, and she answered, “By the way they’re packaged.”

Your package will be competing with all those other pounds of freelance material when it arrives. The secret to marketing your pictures is to match your PS/A with the correct Market List. However, if the editor never sees your pictures because of faulty packaging, they won’t get a chance.

Use an envelope that is trim and sturdy and that stands out. I recommend large white mailers made of stiff cardboard. They give an excellent appearance and have a slotted end flap that makes them easy and fast to open and close. Buyers can use the same mailer to return unused photographs. (Since you can’t be sure the buyer will automatically reuse your envelope [or mailing carton, as it’s called in the industry], have a rubber stamp or label made that reads: “Open Carefully for Reuse” or “Mailer Reusable.” Stamp or put the label on the flap of the envelope.) The mailers can be recycled several times since they are made of heavy material and hold up well. Place your new address label over the existing label, and place white self-apply labels (available at stationery stores and through computer sales catalogs) over previous stamps and markings. A distributor of white cardboard mailers is:

• Mailers Company, 575 Bennett Road, Elk Grove Village, IL 60007; (800) 872-6670, www.mailersco.com.

This type of mailer also saves you from having to pack your photographs between two pieces of cardboard, wrap rubber bands around them and then stuff the result into a manila envelope. You can understand why, when editors have to unwrap this type of submission twenty times a day, they welcome a submission in a cardboard envelope, where pictures tucked in a plastic sleeve slide out and in easily.

Manila envelopes also have another disadvantage. Postal workers tend to identify the manila color as third class. Also, photo buyers might think of your photos as third class, and worse, you may think they are. Go first class and mail in a white envelope. It will help your package receive the tender care and respect it deserves, both coming and going.

As long as we’re judging the book by its cover, invest in some personalized, self-stick address labels. Your reliability factor will gain points if your logo on the labels is distinctive. Also use this opportunity to display your company’s unique slogan. Have return labels printed with your name and address, and include a label on the inside of your package, with return postage, which the editor can apply to your reusable mailing carton.

HOW TO SEND YOUR SUBMISSIONS

Assuming you use the U.S. Postal Service, you will find that Priority Mail treats your packages with respect and moves them quickly to their destinations for the least cost. Priority Mail is placed in the first-class bin. For added impact, you can place your white mailer (onto which you can affix your return address label and postage) inside the Priority Mail Tyvek package. You can get this free at your local post office or have it delivered free through the Internet.

If you need to know that your package reached its destination, Delivery Confirmation is included in the fee for your Priority Mail shipments.

Courier systems such as FedEx and UPS are popular with stock photographers, especially if you’re dealing with a buyer new to your Market List. The advantage of couriers is that your submission is tracked during its journey to the photo buyer, and the couriers usually hand deliver directly to the photo buyer and obtain a delivery signature.

You might want to consider insuring your U.S. mail package. (The best bargain is the $1–50 coverage, for $0.75. Postal rates change, so check the www.usps.com website for current information, or call your local post office.) Keep in mind that in the event of damage or loss, the U.S. Postal Service considers your pictures worth only the cost of replacement film. Your main reasons for getting insurance will be the extra care it guarantees your package and the receipt the delivery person collects from the recipient. The post office will have documentation that your package arrived, if you need to trace it. For less than a dollar more, you also can have a return receipt sent directly to you. This document can come in handy if the photo buyer ever says, “I didn’t receive your shipment.”

Shipping your photos by registered mail is good insurance, too, of course, but expensive. I’m aware that many photography books recommend sending your shipment via registered mail. I’m also aware that the authors of those books are not engaged in stock photography as their principal source of income.

Insuring or registering your photos for $15 or $1,500 will not ensure that you will receive that amount if they’re lost or damaged. You will have a case only if you have receipts showing how much you have been paid for your pictures previously. Otherwise you’ll receive only the replacement cost—about $0.50 for each slide or print. The best insurance is prevention. Use the packaging techniques I’ve described here, and you will have little or no grief.

If you’re just starting out in stock photography, include return postage in your package. Most buyers not only expect it, they demand it. Some refuse to send photographs back if return postage is not included. Purchase a small postal scale at a stationery store, and you can easily figure your postage requirements at home.1

There are three acceptable ways to include return postage, described as follows.

- If you use a manila-envelope packaging system (which is not recommended, as discussed earlier), affix the stamps to a manila envelope with your return address, fold and include in your package.

- Place loose stamps for the amount of the return postage in a small (transparent) coin envelope, available at hobby stores. Tape (don’t staple) this envelope to your cover letter. The advantage of this method is that often the photo buyer will return the stamps to you unused. You can interpret this as a sign that the photo buyer is encouraging you to submit pictures again in the future.

- Write a check from your business checking account for the amount of return postage. Make it out to the organization (publishing house, agency and so on). Your reliability factor will zoom upward, and nine times out of ten you’ll receive the check back, uncashed. Besides, the organization’s bookkeeping department probably has no accounting system for such checks. Another advantage: By rare chance the client happens to lose or damage a print and reports to you that he has no record of receiving the pictures and yet if he cashed the check, you would have proof that he received your submission.

Writing the Cover Letter

Always include a cover letter in your package, but remember that photo buyers must sift through dozens of photo submissions weekly. They don’t appreciate lengthy letters that ask questions or detail f-stops, shutter speeds or other superfluous technicalities. Such data is valid for salon photography or the art photo magazines but not for stock photography.

If you do feel compelled to ask a specific question (and sometimes it’s necessary), write your question on a separate sheet of paper and enclose an SASE for easy reply. Better yet, send your question separately from your photo submission, and only send it after you’ve tried to find the answer to your question on the organization’s website.

The shorter your cover letter, the better. Your personal history as a photographer, or where and when you captured the enclosed scenes, is of little interest to the photo buyer. All you need in the cover letter is confirmation of the number of photos enclosed, your fee and the rights you’re selling. Let your pictures speak for themselves. However, include extensive caption information for each image. As mentioned earlier, it can lead to sales.

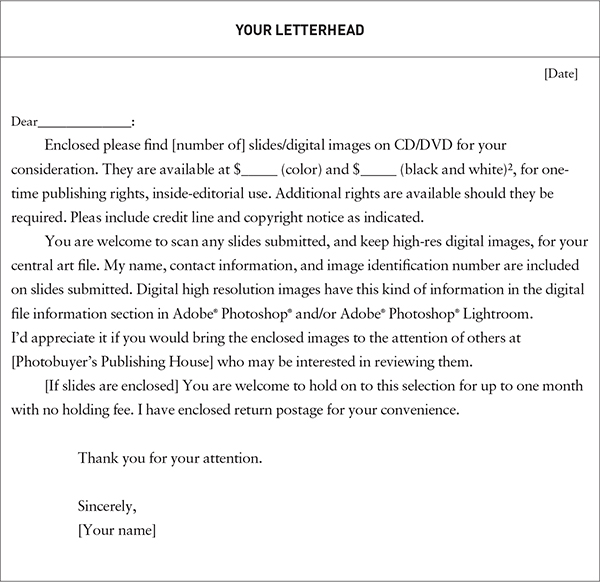

Address your cover letter to a specific person, whose name you’ll find by consulting your Market List or the agency’s website, or by calling the agency’s reception desk. A typical cover letter might read like the one in Figure 9-1.

This cover letter may not win any literary awards, but it’s the kind photo buyers welcome. It tells them everything they want to know about your submission.

Photo buyers like to deal with photographers with a high reliability factor—photographers who can supply them with a steady stream of quality pictures in the photo buyers’ specialized interest areas. They don’t want to go through the time-consuming process of developing a working relationship with photographers who can supply only a picture or two every now and then. The right cover letter will signal to the photo buyer that you are not a once-in-a-while supplier.

Figure 9-1. Sample cover letter to send with unsolicited submissions to photo buyers.

If you have learned of a specific need that a photo buyer has (through a mailed photographer’s memo, an announcement in a photo magazine, or a listing in a market service such as PhotoLetter, PhotoDaily, AGPix or Visual Support/Photonet), what kind of letter should you send? Again, keep your letter brief. Include many of the details listed in Figure 9-1. However, also include the number or chapter of the book, brochure or article for which the photos have been requested. Photo buyers often work on a dozen projects at a time. Knowing which project your pictures are targeted for helps!

Use a form letter if I’ve convinced you; otherwise, send a neat word-processed letter.

FIRST-CLASS STATIONERY

To make a professional impression, design your cover letter as a form letter. Use your word processor, and have the letter printed at one of the fast-print services on 24-lb. or 28-lb. off-color business stationery. Scan in your letterhead and logo for a first-class appearance. Leave the five blanks in your letter to fill in by hand for each submission (see Figure 9-1).

Photo buyers will not be offended by receiving a form letter but rather will welcome it as the sign of a knowledgeable, working stock photographer. The message the letter telegraphs is that this is a working stock photographer. Someone who has gone to the expense of a printed form letter on quality stationery has more than a few photographs to market. If the pictures you submit are on target and you include an easy-to-read, concise form letter, you are on your way to establishing yourself as an important resource for the photo buyer.

Deadlines: A Necessary Evil

Because photography is only one cog in the diverse wheel of a publishing project, photos are necessarily regarded by layout people, production managers, printers and promotion managers not as individual aesthetic works but as elements of production value within the whole scope of the publishing venture. Book and magazine editors often tend to treat photography as something that should support the text, rather than the other way around. Hence, they load photo editors with tough deadlines. If your photographs are due on such and such a date, the photo editor is not kidding. Being on time can earn you valuable points with a photo buyer, and it can mean the difference between a sale or no sale.

Develop the winning habit of meeting deadlines in advance. It will increase both your reliability factor and the number of checks you deposit each month.

Unsolicited Submissions

The word on the street is that photo buyers look upon unsolicited submissions with disdain. This is partly true. If you were an editor of an aviation magazine and I sent you, unsolicited, a couple dozen of my best-quality horse pictures, you’d be righteously perturbed. However, if I sent a group of pictures, unsolicited, that were tailored to your needs, and showed a knowledge of aviation plus some talent with the camera, you’d be delighted, especially if I sent you an SASE for those you couldn’t use.

“Most freelancers send me views of birds against the sun or close-ups of flowers, and maybe a kid with a model sailboat. Don’t they even look at our magazine?” an editor of a sailing magazine asked me.

You can understand why some editors tend to lump freelancers and unsolicited pictures into the category of “undesirable.”

If you’ve done the proper marketing research, photo buyers will welcome your unsolicited submission. On the other hand, if you haven’t figured out the thrusts of the magazines or the needs of the publishing houses, don’t waste your time or postage and earn their ire by submitting random photos. You won’t last long as a stock photographer, no matter how good your pictures are. Ask yourself before you send a shipment: “Am I risking a no-sale on this one?” Choose a market whose needs you’ve pinpointed—one that you’re sure to score with.

Digital delivery on CD-ROM is a great way to send unsolicited submissions to photo buyers; you can fit many high-resolution images on a CD-ROM, and it’s cheaper to mail a CD-ROM than it is a selection of originals. It’s also cheap to make extra copies of CD-ROMs. Make sure that your digital images are in a commonly accepted format such as JPEG or TIFF and that the photo buyer is willing to accept images on a CD-ROM. As I said earlier, the transition to digital is a slow process for the photo buyer community.

The Magic Query Letter

If you’ve advanced to a stage in your photomarketing operation in which you’re prepared to contact multiple markets on your list, here is an introductory, or query, letter system that will prove helpful. This system is designed to hit the right buyer with the right photograph every time.

The age of the general-audience magazine ended with the weekly Look. General-audience magazines are being replaced by the special-interest magazines, which contain subject matter ranging from hang gliding to geoscience to executive health. The diversification continues. Gardeners have their interests featured in magazines covering houseplants, ornamentals, backyard farming, organic gardening, flowers and so on. Boat enthusiasts have special magazines that range from sailboats to submarines. Horse lovers have their own private reading: magazines on the Arabian, the quarter horse and so on. Why venture into fields of little or no interest to you when you’re already a mini-expert in at least a half-dozen fields that could provide you with more than enough markets to choose from?

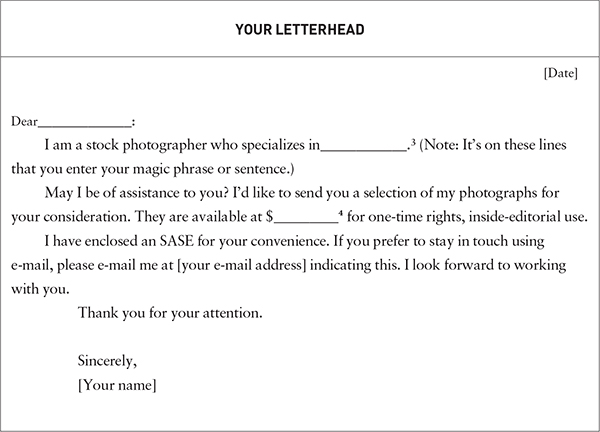

The key to the magic query method is an initial query letter to each prospective editor. What you say in this letter will move the editor to invite you to submit your photographs.

The query letter, to be effective, must be brief and simple, yet spur the editor to reply immediately and request your submissions for consideration. Here’s how to plan your letter, individualized for each market.

Immediately hit the buyer where his heart is: In your first sentence, include a magic phrase that will grab his attention and rivet him to your letter. It will take some research on your part, but once you’ve worked out that magic phrase, not only will your letter be read, it also will be hearkened to and acted on. The query letter in Figure 9-2 provides a useful model for you to follow.

Figure 9-2. The magic query letter

The majority of publications today are designed for specialized audiences. Imagine the structure of a special-interest magazine as a pyramid. At the base of the pyramid are the thousands of readers and viewers who are fans of this special area of interest. Next on the pyramid are the people with an economic interest in this specialized area: the advertisers. Farther up are the creative and production people who put the magazine together—the writers, designers, layout artists, printers, photographers and so on. At the top of the pyramid is the publishing management. The pinnacle of our pyramid contains the concept, the idea or the theme upon which the magazine is based.

Now, here’s the key to that magic phrase. Outside appearances would have you believe that the essence of, say, a magazine called Super Model Railroading would be model railroads. You’re only one-eighth right. (This is where most suppliers—writers, graphic designers and photographers—lose the trail when they initially contact prospective editors.) Here’s the essence of Super Model Railroading: to allow adults the license to buy and play with expensive toys.

In the first sentence of your query letter to the editor of this magazine, you would use a magic phrase like, “I specialize in photographs of people enjoying their hobbies.”

Let’s look at another example. A magazine called Today’s Professional RN would appear to have professional nursing as its theme. Yes, that’s the magazine’s stated theme. But what is its unstated theme—the subject that touches the hearts of its readers and therefore the publication’s management? The essence of Today’s Professional RN: to remind nurses that they deserve the respect and esteem accorded to other community health-care professionals such as physicians, psychologists and dentists.

In the first sentence of your query letter, you would use a magic phrase like “I specialize in health-care photography and have in my stock file a large selection of pictures showing nurses playing a key role in our health-care system.” The editors of specialized magazines are always looking out for their readers, advertisers and bosses. If the first sentence in your query letter indicates that you can help in that mission, the editor will say to herself, “Now here’s a person who speaks my language!”

Your job as a query-letter writer becomes one of separating illusion from reality in the publishing world. As you can see, it will take some study on your part, but the study becomes pleasurable if you direct your research to magazines you already enjoy reading. Make a game of distinguishing between a magazine’s stated theme and its real theme. You’ll be surprised how easily you learn this technique, especially for the magazines on your Market List.

What is the reaction of an editor who receives a query letter that shows no preparation on the part of the photographer? He feels insulted. He runs a tight ship. He has deadlines. He trashes the letter. He’s not about to show any consideration to a photographer who has not shown him the courtesy of studying his magazine.

If you’ve done your job in your first sentence, and your first paragraph shows you are interested in both the magazine and the photo editor, you will have his attention. He will be alerted to your inventory of pictures, but beyond that, a couple more ideas will occur to him.

- If you’re an informed photographer (in his field), you are a mini-expert and therefore a valuable resource to him, and you could be available for assignments.

- Although you’ve said you have certain photographs that you believe to be adaptable to his needs, you might have many more photographs that are adaptable to his needs. For example, perhaps his publishing firm is starting a sister publication and is on the lookout for additional pictures in an allied area of interest.

The second paragraph of your query letter should confirm the attitude expressed in your first paragraph, namely, that you are aware of his photo needs.

How do you become aware of those needs? By studying the magazines you find in libraries, dentist offices, friends’ homes and business reception rooms. Websites and photomarketing directories, such as Photographer’s Market and those listed in Table 3-1 on pages 56-57, describe thousands of magazines and list them by special-interest areas.

Before you send your query letter to an editor, request her photographer’s guidelines. Most magazines provide a sheet of helpful hints to photographers, and if you contact the photo buyer on deluxe, professional stationery, complete with your logo, and you include an SASE, she’ll send a sample issue of their publication as well.

Now you are ready to write the magic query letter. Figure 9-2 is a sample of how your query letter should look.

You’ll notice in the magic query letter that there is an abundance of Is. This may seem contrary to your writing style (or training), but those Is are there for a purpose: to give the editor the impression that this new recruit is dynamic, aggressive and self-centered. (Note: Welcome to the world of business! If being dynamic, aggressive and self-centered turns you off, you’ve got to reexamine and adjust your thinking. Timidity, modesty and humility are nice attributes, but not if you want the world to see your pictures.)

In this letter there is a good balance with the word you. (Most schools of persuasive writing teach that you is the most beautiful word in the language.) Your job as a letter writer is not really to inform an editor, but to move her to action, to make her want to see and buy your pictures. The magic query letter will put you leaps ahead of your competition because editors will act.

Should You Deal with Markets Outside of the United States?

Once you’re settled into dealing with domestic markets for your stock photography, you might want to investigate the thousands of international markets, some of which might be target markets for you. The easiest way to break in is to work with an established international stock photo agency. Digital possibilities make it even easier to show and sell your work internationally by placing it on a website (your own or an agency’s) and by participating in international stock directories.

Photographer’s Market publishes an excellent listing of international stock agencies every year, including a number of Canadian agencies. If you’d prefer to sell by yourself, start by using the Internet search engines. Other great sources of information are foreign embassies. All embassies have a press or information department that will direct you to their website as well as help you with requests of information about publications in their country.

Another popular guide to overseas marketing of photos is Michael H. Sedge’s The Writer’s and Photographer’s Guide to Global Markets, available through Amazon books (www.amazon.com).

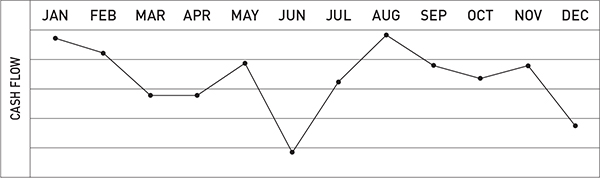

Which Are the Heavy Purchasing Months?

Recently I sent a questionnaire to one hundred photo buyers asking which months of the year were their busiest in terms of picture-buying. Table 9-1 indicates that the thirty-five photo buyers who responded shared one of two prime purchasing periods: midwinter and midsummer. With more than four decades of experience as a stock photographer marketing by mail, I can confirm that these are heavy purchasing periods for a good proportion of the publishing industry.

Publishers are working on either a fiscal (July 31) or a calendar (December 31) year, which means cash flow is down in July or December and up again in August or January.

Knowing this can help you market more accurately. Your marketing strategy calls for periodic mailings of stock photos for consideration. Note in Table 9-1 that you can increase your chances of scoring if you aim at the midwinter and midsummer months.

Don’t forget: When preparing seasonal pictures, find out the lead time (usually about six months) for your individual markets. In other words, be prepared to send springtime pictures in September. Photo buyers usually work that far in advance.

Before you decide that you have photomarketing down to a formula, though, don’t forget that Table 9-1 represents only thirty-five publishing houses. Also, some of the photo buyers, such as Rodale Press and Highlights for Children, reported that “All months are equally busy.”

|

If your Market List leans toward textbooks, you’ll want to consider this: Many textbook companies work with two different printing dates during any given year—June, for the regular September delivery date on textbooks, and December, usually the month of kickoff sales meetings, when all new special books and textbooks are presented to the sales staff for the coming year’s sales efforts. You can figure that picture selections for books and textbooks are made anywhere from two to four months before the printing date. This average, of course, is relative and subject to variations (both yours and the photo buyer’s), so be sure to consider Table 9-1 only as an indication of what happens much of the time, in much of the market—and balance this against your PS/A, Market List, experience and schedule.

How Long Do Photo Buyers Hold Your Photos?

“The photo buyer is holding my pictures an unreasonably long time, don’t you think?” a photographer recently asked me. He had sent his pictures six weeks previously.

“Not so,” I said. “Especially if the photo buyer makes a purchase.”

The buyer subsequently bought the pictures in question. Everyone was happy.

How long should a photo buyer hold your photos? Two weeks to two months is a safe answer, but it could be even longer. Magazine editors, for example, will hold your pictures about two weeks, sometimes four. However, if you’ve requested in your cover letter that the editor circulate your submission to others at the publishing house who might be interested in reviewing them, and the publishing house is large, you may not see your pictures again for six weeks.

If you’ve directed your pictures to a book or textbook publisher, they could remain there for as long as eight weeks (up to six months for a textbook publisher). Book production schedules often require more complex dovetailing and coordinating than magazine schedules.

Ad agencies and public relations firms are less likely to hold your pictures for an unreasonable length of time. The reason? They’re usually working on tight deadlines. Their decisions must be quick.

You won’t notice how “unreasonably” long photo buyers are holding your pictures if you multiply your marketing efforts: Make in-camera duplicates of your slides, copies of your CD-ROMs and duplicates of your black and whites. Offer your images to noncompeting photo buyers on your Market List simultaneously. Establish a “lightbox” website where photo buyers can go to see your most recent portfolio.

Here are a few variables that can result in photo buyers holding your pictures for a while:

- The deadline for the project (textbook, brochure, article) has been extended, giving the buyer more time to make a decision on your pictures.

- The buyer likes your pictures and has set your package aside for further consideration.

- The buyer likes your picture but wants to do a little more shopping in case he can find something even more on target.

- The photo buyer has forwarded your pictures to the author (of the textbook, book and so on) for consideration. The author is holding up the decision.

- The buyer’s priorities have changed and your picture is now in the number two (or number six) priority stack.

- The photo buyer is a downright sloppy housekeeper and your pictures won’t surface until spring housecleaning time. (Fortunately, very few photo buyers are in this category.)

If a photo buyer keeps your pictures longer than four weeks (and you are certain the selection date has passed), drop her a courteous note. You can expect a form-letter reply letting you know of the disposition of your pictures. Textbook editors hold pictures longer, as mentioned earlier. Usually if a picture lingers at a textbook publisher’s, you’ll be notified within three months that it’s being held for final consideration.

However, when most editors (textbook editors included) look over photography (especially general submissions), they attempt to review pictures the same day they arrive. If none of the pictures are to be considered for publication, the editor will have them shipped back the following day. This makes good sense both for insurance purposes and for office organization. If one or more of your pictures is being considered for publication, the photo editor might hold your complete package until a decision is made.

Again, the best solution to the “unreasonable” length of time a photo buyer may hold your pictures is to follow the four suggestions mentioned previously. You’ll be so preoccupied with sending your photos out and reaping the rewards that you won’t have time to track down tardy photo buyers.

INSURANCE CONSIDERATIONS

What insurance coverage does a publishing house have that, in case of fire or similar calamity, would cover your pictures being held? In some cases, your slides, prints and digital images would be considered “valuable documents” and be replaced accordingly. Generally speaking, publishing houses have a blanket insurance policy on your photographs. This blanket policy also includes the company’s office equipment, lighting fixtures and other tools of the trade.

Nevertheless, publishing houses do not like to keep your pictures any longer than they have to because as long as your pictures are in their possession, they are responsible. Between your place and theirs, the U.S. Postal Service, FedEx or UPS has that responsibility—if you insure your package. (Note: FedEx, UPS and other carriers will insure all your packages for free to a maximum of one hundred dollars, but they will reimburse for loss only the amount of replacement. You can declare a higher value and pay a higher fee. However, unless you can prove the value of the prints, transparencies or discs, you’ll receive only the minimum fee unless you take your case to court, which can often cost more than you would receive in compensation.)

Figure 9-3. Memo to inquire about pictures being held too long.

Figure 9-4. Postcard form for editor’s reply about late pictures. On your return reply postcard make it fast and easy for the photo buyer to get back to you with little to no effort on their part while you still look and come across as professional. If you have a really good laser printer, you can make your own postcards using Avery or similar brand products. Formatted templates for the products can typically be found on the manufacturer’s website.

USING POSTCARDS TO RELIEVE THE AGONY

If not knowing the disposition of your photos is frustrating to you, take a tip from stock photographers who include a return postcard with their submissions. The stamped card is addressed to the photographer and says, in effect, that the photo shipment was received by so-and-so on such-and-such date.

Another effective contact with a photo buyer would be a memo on your letterhead with the message shown in Figure 9-3. The accompanying postcard reads as shown in Figure 9-4.

A HOLDING FEE—SHOULD YOU CHARGE ONE?

As mentioned before, some editors must of necessity hold your picture(s) for several months. This in effect takes your picture out of circulation. If it’s a timely picture, such as a photograph of performers who will be in town in two weeks, or a photograph taken at the fair that ends this week, you could lose sales on it. By the time it’s returned to you, it could be outdated and have lost its effectiveness. To compensate for this potential loss, the holding fee was born. (Happily, most of your stock photos are universal and timeless if you’ve applied the marketable-picture principles of this book.) Some photographers charge a holding fee for pictures held beyond two weeks. The holding fee ranges anywhere from $1–5 per print per week for black and whites, to $5–10 per photo per week for color.

To make a potentially lengthy discussion short: Don’t charge a holding fee unless you’re a service photographer dependent on quick turnover of your images or you’re an established stock photographer working exclusively with range 1 (see Table 8-1 on page 113).

You may want to disagree with this advice. You’ll have to be the judge for each situation. Generally speaking, editors will frown on an unreasonable holding fee and on you, especially if you are a first-time contributor to them.

As I mentioned, here’s the secret to overcoming the possibility of losing sales on your timely pictures: Make duplicates and have several of them out working for you simultaneously.

Sales Tax—Do You Need to Charge It?

Not every state charges sales tax, but if you live in a state that does, contact your State Department of Revenue for details. If you make a sale within your state, you need to charge sales tax unless the sale is to a state or federal government agency. (You can forgo charging your photo buyer the necessary sales tax and pay it yourself by sending the appropriate sales tax amount on an annual or semiannual form to your state’s sales tax department.) If the sale is to an address outside your state, no sales tax is required. Generally, most stock photographers deal long-distance and sell outside their own states.

In California, the State Board of Equalization addressed the question of one-time use of photographs with this ruling: “Photographers who license their photographs for publication should be aware that merely because the photographer owns the rights to the photographs and retains the negatives, does not mean that a sale has not taken place. The transfer of possession and use of a photograph for a consideration (license fee) is a sale and is subject to state sales tax. There is only one exemption to the above, which is for newspaper use—but not for magazines or any other commercial use—even if for ‘one-time use only.’ ”

You’ll need to check what your state’s policy is and make sure you are in compliance.

When Can You Expect Payment?

Most photo buyers on your Market List will pay on acceptance rather than on publication. If they don’t, drop them to the bottom of your Market List. After all, your PS/A matches only certain markets, but you bring to those markets an exclusive know-how that other photographers do not possess. You are an important resource to editors. Be proud of your talents. If some editors don’t reward you with payment on acceptance, replace them.

Photo buyers usually send a check to you within two to four weeks after they’ve made their decision to purchase. However, each publishing house works differently: Some pay more quickly, others take longer in their purchase-order and bookkeeping procedures. However, if a publishing house has a $30,000 a month photo budget—not a high figure in the photo-buying world—and is slow in paying, I’m sure you won’t be too irate if the checks addressed to you customarily arrive a little late each month. Many publishing houses across the nation have $30,000 a month photo budgets or close to it, and they’re seeking your pictures right now. If one publishing house is late with its payment, spend your energy sending the others more pictures, rather than composing letters of complaint. (If you’ve built your Market List correctly, you’ll find few deadbeats in it.)

How Safe Are Your Pictures in the Hands of a Photo Buyer?

Contrary to popular opinion, photo buyers do not have machines that zap discs, split and crack 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm) prints, scratch and crinkle transparencies and sprinkle coffee over all three. Your submission will receive professional handling if you’re careful to submit only to professionals. If you aren’t sure whether a publishing company is new to the field, check a previous edition of Photographer’s Market or a similar directory (one reason to keep back editions of such directories). If the house was listed three years ago, that’s a factor in its favor.

I receive occasional complaints from photographers about a photo editor’s handling of their pictures. Invariably, mishandling of pictures can be traced to employees of a company new to the publishing business. It’s rare that a publishing house with a good track record will mishandle your submissions. The reliability factor (RF) works both ways: Buyers expect you to be dependable, and you should be able to expect the same from them. If you find that a publishing house projects a low reliability factor, avoid it.

Don’t spend sleepless nights fretting about your pictures. Instead, imagine your stock photography operation as a long tube. You put a submission in one end and keep putting submissions in, moving down the tube. Instead of waiting by the mailbox, put in more time at your computer or in the darkroom, or snap more slides for your stock photo file. Keep the submissions moving down the tube. One day you’ll hear a sound at the other end—the check arriving!

LOST, STOLEN OR STRAYED?

You’ll rarely hear of a stock photo stolen by an established publishing house. Online delivery of stock photos, plus improvements in scanning techniques, makes it easy for just about anyone to “borrow” images. However, a stolen photo that’s subsequently published increases the thief’s chances of being discovered. As the Internet matures, new encryption methods and enforcement of copyright will meet this challenge.

Will your photos get lost? As I mentioned earlier, when a picture is lost, whether en route or at a photo buyer’s office, the record reveals that it’s most often the fault of the photographer.

Here are some common reasons:

- No identification on the pictures or identification that is blurred or unclear.

- Missing, incomplete or unclear return mailing information.

- Erroneous address on the shipment.

- Failure to include return postage (an SASE) when appropriate.

I have talked with many photo buyers who say they have packets of photographs and many single photographs gathering dust in their offices because the photographers didn’t include an address on the pictures. Once pictures become separated from the original envelope, unless they include an identification label the buyer has no way of knowing where to return them. Many orphan photographs hang temporarily on photo editors’ walls—they’re that good!

I’ve lost only one shipment in over twenty-five years of sending out stock photos. I should say temporarily lost, because after five years, the editor’s replacement discovered my ten slides, kept in a “safe place”—in the back of a filing cabinet. My mistake: sending a shipment to a startup publishing house.

Loss of your discs or transparencies is best avoided through prevention: Don’t send original pictures to photo buyers or publishing houses that have no track record. Prevention is cheap, and it’s a good habit to get into in photomarketing.

YOUR RECOURSE FOR LOST PHOTOS

This is not to say that a photo buyer can’t commit an honest error. Let’s say that some of your pictures are lost and the photo buyer appears to be at fault. Your best policy is good old-fashioned courtesy. Otherwise, a good working relationship between you and the photo buyer can break down, sometimes irreparably. Don’t be quick to point an accusing finger and perhaps lose a promising client. Consider the following:

- Have you double-checked to see if the person you originally sent your pictures to is the same person you are dealing with now?

- Have you waited ample time (four weeks for a magazine, eight weeks for a book publisher) before becoming concerned?

- Have you asked if your pictures are being considered for the final cut?

- Have you checked with the postal authorities or courier on initial delivery?

If you definitely establish that your submission arrived and is now lost, three options are open to you, depending on who lost your pictures—the photo buyer or you because of flawed labeling.

When I speak of lost pictures, I am referring now to one or more transparencies, a disc or a group of prints. Photo buyers generally do not expect to engage in negotiations over a single print that they know can be reprinted at much less cost than the cumulative exchanges of correspondence over it between photographer and photo buyer. If a single print disappears, my suggestion is to accept the loss and tally it in the to-be-expected-downtime column.

Transparencies are another story. A transparency is an original. Photo buyers are prepared to talk seriously about even a single transparency—if it has been established that they did receive the image. One excellent way (mentioned earlier) to keep tabs on delivery of your shipments is to invest in a return receipt. The post office will provide you with documentation that someone signed for the package.

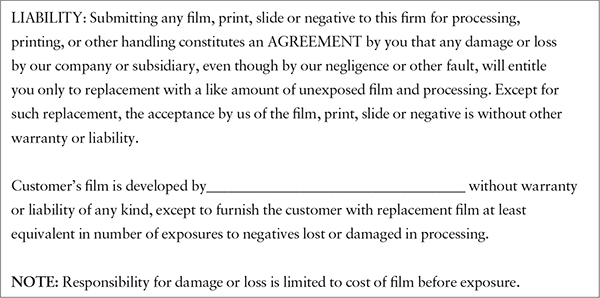

Another protection is a liability stipulation, which you include in your shipment, to the effect that, if the buyer loses or otherwise damages your transparency, his company is liable to you for $1,500.

Does this latter course seem excessive? Many photo buyers think so, and you get on their blacklist if you try it. There’s an old story about Michael Jordan demanding a special jersey number, a special footlocker and white basketball shoes. The coach just laughed at him. Michael was thirteen at the time. Even Stephen King had to settle for less than optimum contract agreements in the early stages of his career. So did Van Cliburn, Tom Cruise and Julia Roberts.

When you’re an unseasoned freelancer, you take what you get. Initially, exposure and credit lines are your prime rewards. Only when you have proved to an art director or photo buyer that you can deliver the goods, and that she needs you, can you call the shots. Until you’ve proved yourself valuable to a photo buyer or publishing house, you’re not in a position to talk liability stipulations.

In this age of malpractice suits, some publishers have become gun-shy because a small but significant number of photographers have pressed suit for loss of transparencies (rarely are prints or discs involved). Consequently, publishers shy away from dealing with new and untried stock photographers, or they take precautionary measures with them, such as having the photographer sign an indemnification waiver that in effect releases the publishing house from any and all liability.

That’s why it’s important to discern who’s doing the talking when you hear seasoned professionals advise that “you ought to require photo buyers to sign liability agreements.” When the professional advises you to get a liability release from the publisher, he just might be using one of the tricks of the trade (any trade) to eliminate competition. He knows that photo buyers will steer clear of you if you summarily present them with a liability requirement. Or it might be an ego trip for the pro to suggest that you get the release. Only the known and the best can make demands, as Michael Jordan eventually learned.

The commercial stock photographer and the editorial stock photographer may have different attitudes toward this liability problem. As an editorial stock photographer, your interest in photography as an expressive medium differs a lot from that of the commercial stock photographer who concentrates on photography as a graphic element in advertising, fashion or public relations. The commercial stock photographers’ rights to sell their services and to protect their business with holding fees, liability terms and conditions, and so on should be honored. However, their business is not editorial stock, and their markets are not magazine and book publishers when it comes to dealing with photo illustrations. Yes, of course, if you’re dealing with a buyer in range 1 (see Table 8-1 on page 113), you’ll probably arrive at some mutually reasonable liability agreement. If you deal with buyers in range 6, the subject may never come up.

How Much Recompense Should You Expect?

Figure 9-5. Liability notice.

The compensation you should expect from a photo buyer for a lost picture is dependent on several factors: (1) the value of the picture to you and to the photo buyer, (2) the anticipated life of the picture itself and (3) which price range (1 to 6) the photo buyer is in.

I have talked with photographers who have received compensation ranging from $100–1500 for an original transparency. A good rule of thumb is to charge three times the fee you were originally asking. If the lost transparency is a dupe, in most cases only the cost of replacement would be in order. One final consideration: Some politics are involved here. Each photo buyer can be a continuing source of income for you. How you handle these negotiations will influence how much of that income continues to come your way.

If you’re still not convinced that a liberal policy toward a photo buyer’s liability is sound, consider this: Two other entities also handle your transparencies, the film processor and the delivery service (U.S. Postal Service, UPS, FedEx). Neither of these entities will accept liability for your transparencies (or prints) beyond the actual cost of replacement of film, disc, and/or paper, unless gross negligence can be proven. You’ve seen this in small print, but as a reminder, see Figure 9-5. (This notice is from a reputable film-processing company.)

The U.S. Postal Service, UPS and FedEx will not award you more than the replacement cost of the film or prints. If you’ve insured your package for the intrinsic value of your pictures, in the event of damage or loss, the carriers will want to see a receipt establishing that value. If you don’t have one, they will pay you only what it would cost you to print the pictures again or have duplicates made. The insurance would not cover sending you back to France to retake the pictures.

If you were a commercial stock photographer and the loss was substantial, and evidence of gross negligence by the courier was involved, you might want to consider taking the courier to court.

Such harsh terms should encourage you to prevent the loss of your film or pictures by packaging them well.

If you have arrived at a point in your own stock photo career where you’d like to test the reaction of your photo buyers to a Terms and Conditions Agreement form, buy a current copy of ASMP Professional Business Practices in Photography ($29.50 at the time of writing). It includes the following sample forms (which you can photocopy or modify): Assignment Invoice, Stock Photo Submission Sheet, Stock Pictures Invoice, Model Release, and Terms of Submission and Leasing (which lists the compensation for damage or loss of a transparency at $1,500). You’ll also find similar forms in a book on commercial stock photography by Michal Heron, entitled How to Shoot Stock Photos That Sell (see the bibliography).

If you’d like to know more about ensuring your rights when a transparency or shipment of black and whites is lost or damaged, here are four references: A Guide to Travel Writing and Photography by Ann and Carl Purcell; The Photographer’s Business and Legal Handbook by Leonard D. DuBoff; Photography: What’s the Law? by Robert Cavallo and Stuart Kahan; ASMP Stock Photography Handbook by Michal Heron, editor.

Remember, the key to successful marketing of your pictures lies in effective communication with the people who approve payment for your pictures—the photo buyers. Your photos may have won ribbons in photo contests, but the real judge of a marketable picture is the photo buyer.

A Twenty-Six-Point Checklist to Success

Sending a submission to a photo buyer? Run your package through this quality control:

Packaging

- Clean, white, durable outside envelope with correct amount of postage.

- Professional-looking label with your correct (legible) return address and logo printed on it.

- SASE enclosed.

- All photos clearly identified: picture number, plus your name and address.

- Copyright notice.

- No date on your slides or prints (unless you use a code).

- Captions when appropriate.

- Transparencies in thick, see-through vinyl pages.

- Cover letter (printed form letter) that is brief and on clean deluxe stationery.

Cohesiveness

- Solicited submission: Pictures are on target as per request of photo buyer.

- Unsolicited submission: Pictures follow style and subject of photo buyer’s publication. They fit the buyer’s graphic and photographic needs.

- Pictures are consistent in style.

- Pictures are consistent in quality.

Quality

Color

- Color balance is appropriate for subject and is suitable for reproduction.

- Dupes are reproduction quality (with proper filtering) or else identified as display dupes.

- Each slide has been checked with a magnifying glass or a loupe for sharpness. No fuzzy shots!

Digital

- Resolution matches the photo buyer’s needs.

- Format is acceptable to photo buyer.

- Delivery method (e-mail, CD-ROM and so on) acceptable to photo buyer.

Black and White

- Good gradation: stark whites; deep, rich blacks; appropriate gradations of grays.

- Spotted.

- Trimmed: Edges are crisp and straight; no tears or dog-ears.

Both Color and Black and White

- In focus, sharp, good resolution (no camera shake).

- Current (not outdated).

- Appropriate emphasis and natural (unposed) scenes.

- P = B + P + S + I. Pictures evoke a mood.

Readers outside the United States who are marketing to U.S.-based companies: Contact your local postal service, purchase International Reply Coupons and include them as equivalent return postage.