15

Rights and Regulations

COPYRIGHT

Who owns your picture? You do! The Copyright Law speaks loud and clear. Copyright law generally gives you, as the author of your photos, copyright for each picture from the moment you press the shutter. Ownership of the copyright enables you to determine or limit the use of every photo in whatever way you specify, to re-sell various rights in the work and to have your rights in your work protected by a court of law in case of infringement.

The easiest way to assert your claim is to affix a copyright notice—© Your Name—to each photo. You also can formally register your picture with the U.S. Copyright Office for a fee (currently $30). You then receive a registration certificate, the prerequisite for taking an infringer (one who has used or reused your picture without authorization) to court. If you don’t register your picture, it’s still protected by copyright as your property, and you still have legal claim to it. However, formal registration helps cement your claim. If you register the image before or within three months of first publishing your work, you have a better chance at receiving fall financial recompense in the event of infringement.

The familiar c within a circle (©) is no longer necessary to preserve copyrights. Late in 1988, the United States ratified an international copyright treaty known as the Berne Convention. This put the final nail in the coffin of the former long-standing rule that a copyright in a published work could be lost if the work didn’t carry a valid copyright notice. (The old rule still applies to photos published before March 1, 1989.) However, using the © will strengthen your copyright protection. It’s still advisable to use it. By doing so you give notice to the public that you are claiming copyright, and you are alerting any potential user as to who the owner is and how to contact you. Print your copyright notice on your slides and mark your digital images as copyrighted in your photo-editing software to eliminate any doubt as to who owns the copyright and to broadcast a warning that infringement will be prosecuted. However, for the record, the copyright in any photo you have published after the March 1, 1989, deadline will be automatically protected, whether or not you have printed the copyright notice on it.

Copyright Infringement

Let me say at the outset that I believe the spirit of the Copyright Law is to encourage the free flow of information in our society. The law is a basic protection for that exchange. It was written to protect not just photographers, but the users of photographs as well—the photo buyers. Copyright infringement in stock photography is rare (as opposed to service photography, where infringement does happen). In thirty years as a stock photographer, I have personally experienced only one instance of possible infringement, and in that case an art director, new on the job, made an honest mistake.

If you wish to be super safe, you can register your extra-special marketable pictures. When you do, you’ll receive the benefit of the Copyright Office’s documentation and recording, and you’ll have copies of your work filed with the Library of Congress. However, in stock photography work, you generally won’t find it necessary to register many pictures. The © symbol affixed to the back or front of your picture or next to your credit line in a layout serves as a warning to would-be infringers. The right to use the © is yours; it costs you nothing. The law recognizes that you own your picture once you have shot it, even if it has not yet been processed. The Copyright Act of 1976 is, in effect, a photographer’s law rather than a publisher’s law.

Remember, a copyright protects only your picture, not the idea your picture expresses (Section 102 [b]). If you improve someone else’s idea with your picture, that’s not necessarily copyright infringement, that’s free enterprise. The test for infringement is “access plus substantial similarity.” How similar is substantial similarity? That’s anybody’s guess, but bear in mind that the jury that decides the case is drawn from ordinary citizens. How do you think such persons would feel about a photo you’ve created that shows similarity to another? Keep in mind also that among the rights of the copyright owner is the right to prepare “derivative works.” If your photo appears to be derived from someone else’s photo to which you had access, you may be infringing. On the other hand, don’t be intimidated or deterred from creating or re-creating a new photo on the remote chance it may infringe on an existing photo. After all, the engine of the world of art is fueled by creative improvements to old ideas.

Group Registration

Another option—and to the photographer, quite an advantage—is that under the revision, you can “group-register” photographs. There are different rules for group registration, depending on whether you’re registering published or unpublished images. Currently you can register a maximum of five hundred previously published photographs at a time. The photographs need to have been published during the same year. So, if you have work regularly published in magazine A and newspaper B, you can have all the images registered at once by sending in one year’s worth of copies of your published work, along with the fee and all forms. The fee is currently $30, but check with the Copyright Office to find out the latest details.

You can register an unlimited number of unpublished photos for a one time $30 fee. Unpublished works may be reregistered after publication. Registering unpublished works usually is unnecessary but can expedite getting into court in the event a work is infringed. Moreover, it entitles you to sue for punitive awards (if not registered, you’re limited to damage awards only, which must be proved).

Again, omission of a © notice adjacent to your photo does not void your copyright. In addition, the picture will still be protected by the publisher’s copyright notice, usually included in the masthead, which protects all editorial matter and photographs (except advertising) within the publication.

How to Contact the Copyright Office

For more details on specific points about copyright, phone the U.S. Copyright Office, (202) 707-3000, between 8:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M. (Eastern time), or write: Register of Copyrights, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20559. You can also visit them on the Web at www.copyright.gov.

The Copyright Law is lengthy (the official law is 117 pages) and covers all aspects of creative endeavor, from book publishing to motion pictures. We’ll be addressing here only the portions of the law that relate to stock photography.

Interpreting the Law

Writing and commenting on “the law”—any law—is like discussing philosophy or religion. A point of law might be stated one way, but it’s open to different interpretations. Only time and court tests solidify the interpretation. Even then, there are exceptions to the rule. As each stock photographer’s Market List and PS/A are different, so is the photographer’s need to interpret the Copyright Law. I have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this chapter, checking it with copyright officials and attorneys, but I cannot guarantee the absence of error or hold myself liable for the use or misuse of this information.

To sum up the points of law covered so far:

- You own your picture unless you have signed a work-for-hire agreement (discussed later in this chapter).

- You can register your pictures for added protection.

- You can group-register your photos for a reasonable fee.

Be Wary of Dates

Note that copyright of your pictures published in copyrighted publications prior to January 7, 1978, when a new, broader copyright law (which I’ll address in a moment) went into effect, belongs to the public, in each case, unless you can show proof that you leased the pictures on a onetime basis or that the publisher reassigned all copyright privileges to you. It’s doubtful that this situation will cause you any problems, unless the picture concerned is one with great market potential (such as a photo of a person who recently catapulted to fame). Nevertheless, pre-1978 pictures generally have copyright protection from infringement if they were published with the © symbol, and it may even be possible for you to assert your sole right to them at the time of renewal (more about this later).

Though your rights in pictures published before 1978 may be limited by the arrangements you originally made with the publisher, pictures taken before 1978 but not published until after 1978 will enjoy the benefits of the revised Copyright Law.

Now for the bad news. It’s possible for you to lose the right to your pictures and for them to fall into public domain. Here’s how it can happen: If your work was published without your copyright notice before 1978, or if it was published before March 1, 1989, and neither your copyright notice nor a general notice for the entire publication (such as in the masthead) were involved, and if you did not register that picture within a period of five years from the date your picture was published, then the Copyright Office will now refuse to register your picture. The Copyright Office takes the position that your copyright has expired and that your picture belongs to “the people.” It’s in the public domain: Anyone can use it.

To register a work that has been published without notice (before March 1, 1989), it must have been within five years of publication (and that deadline has long since past). In addition, you will have to show the Copyright Office that either (1) the notice was omitted from only a relatively small number of copies distributed to the public, (2) a reasonable effort has been made to add notice to all copies distributed once the omission was discovered, or (3) the notice was omitted in violation of your express requirement, in writing, that your notice appear.

For current work (after March 1, 1989), the Berne Convention makes it unnecessary legally to have to include a © notice, but as stated in the beginning of this chapter, for the public it’s still a good safeguard to stamp (or write) your © notice on all photos you send out. In your cover letter, state that if the photos are published, your © notice must appear beside them. An official © notice consists of the word copyright or the abbreviation copr. or a © symbol and your name (© Your Name). The use of a “c” in parentheses “(c)” is not a valid copyright symbol.

Since the Berne Convention relieves you of the necessity of having a copyright notice on your photos published after March 1, 1989, it’s no longer critical for you to insist that your © notice be published alongside your photo for the purpose of establishing that you hold the copyright. Again, though, it’s still helpful to attach the © notice to your photos to give warning to would-be infringers.

The revised Copyright Law offers the machinery to protect your ownership of your pictures, but ultimately the burden of protecting your rights is on you.

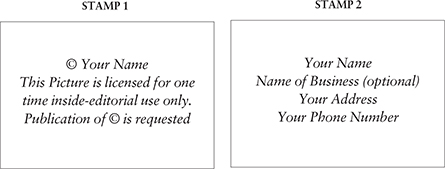

Figure 15-1. Stamps to protect your prints.

The Copyright Office can offer you no protection if you have relinquished your rights through neglect, ignorance or your own wishes. Moreover, the U.S. District Attorney can prosecute only if an infringement is willful and for commercial advantage.

Your © notice on your slide or print is your first order of protection.

Laying Claim to Your Picture

The Copyright Law doesn’t specify what else you should have on your picture for identification, other than the notice. (Always copyright under your name, not the name of your business. Otherwise, if you sell your business, the copyright to all your pictures would go with it.) For your own identification purposes, however, always include your address and phone number. Do the same with your digital images and add the information directly embedded in the photo file.

Your slides will require an abbreviated form of the labels shown in Figure 15-1 because of the border-size limitation, but be sure to include all the information on your accompanying invoice.

The following are sound reasons for going to the trouble of a memo label.

- Licensed implies that this picture is not work for hire. (In work for hire, the copyright may not belong to you.) Licensed implies that you have not entered into any separate sales arrangement with your client, that you want any transparency returned to you.

- One time ensures that you’re not assigning any rights other than rights to one-time use. If you wish, include this sentence in your invoice: “Additional rights available.”

- Inside-editorial use simply lets the client know that if he decides to use your picture on a cover, he must pay extra. (See Table 8-2 on pages 117-119 for how to increase your fee when a picture is used for a cover, for advertising and so on.) This phrase also will protect you in the future if an art director happens to use your picture without authorization for commercial (trade) purposes or advertising. If a suit were to arise relating to trade and advertising use because of the people pictured in the photograph, you could show proof that the picture was leased only for editorial purposes (which usually require no model release).

- Include © credit. This shows proof, in case of infringement, that you asked the publisher to name you as copyright owner.

Some Drawbacks of the Copyright Law

INFRINGER (Section 501 [a]): Someone who violates any of the exclusive rights of a copyright owner.

Prosecuting an infringement may be costly, and you may never recover all the money you expend, but if you prevail, you may be able to seize and destroy the infringing articles, or enjoin the infringer from further production and distribution. This may be worth more than money to you.

Your greatest protection may be to place the copyright notice on each of your pictures. (Remember, the notice costs you nothing.) An infringer is not “innocent” if she pirates a picture that bears your copyright notice. It carries clout. Like the average citizen who never removes the mattress label “Do Not Remove Under Penalty of Law,” the infringer is likely to shy away from anything that looks like a federal offense.

In a rare instance, you might discover an infringer within three months after you’ve published an unregistered picture. If you choose to press charges, you can register your picture at the Copyright Office (special speedy handling will cost you, at this writing, an extra $500—by certified check!), and haul the infringer into any court having jurisdiction in a federal civil action. If it’s past the three-month deadline, you can still register your picture, but damages you would receive if you won the case would be limited.

The process of registration is simple for authors who register an entire book for twenty dollars. For stock photographers, who produce thousands of pictures, the administration and expense of registering each photo might be likened to separately registering each paragraph in a novel or textbook, unless you group-register huge batches. As stock photographers, then, we continue to be left to the mercy and basic honesty inherent in most people. God won’t save us from “innocent infringers,” but we can do a lot to eliminate their “innocent” status by putting notice on every photograph that leaves our hands.

A Remedy

If you discover a person or an organization has used your picture without your permission, send the person a bill. How much? The normal is $300–500. If the person has “deep pockets,” go ahead and charge him $1,500, an acceptable fee for color transparencies in the commercial photo community.

Under copyright law (Section 113 [c], 107, the “fair use” doctrine), libraries, schools and noncommercial broadcasters (such as public television) can sometimes use your pictures without requesting your permission, provided their use is limited to educational and noncommercial activities and does not diminish the future marketing potential of your picture.

This latter ruling will need further interpretation because of the paradox involved when a picture receives wide exposure. Consider the broadcasting of pro football: Leagues are still not sure whether broadcasting enhances or decreases gate sales. Hence the blackout provision. This provision of fair use by the nonprofit sector, which has yet to be fully tested in court, could greatly disadvantage the stock photographer. Fair use is, however, limited by many of the provisions detailed in Copyright Office Circular 21, which describes some of the limitations on fair use. If your work has been used extensively, the use may not be “fair” (reading Circular 21 may shed some light on this for you).

Q and A Forum on Copyright

In the following Q and A forum, I’ll give detailed answers to some significant questions as they apply to you, the stock photographer. I’ll first cite the source in the Copyright Law of 1976 (Title 17 of the U.S. Code).

Is it necessary to place a © notice on all of my photos to preserve my copyright?

Sections 401, 402 and 405

No. As of March 1, 1989 (per the Berne Convention agreement), the familiar © is no longer necessary to establish proof that you own the copyright. The law recognizes you, as the photographer, as owner of copyrights of your photos. However, I recommend using the © notice to eliminate any doubt in viewers’ minds (i.e., the public) as to who owns the copyright to your photo. The © notice broadcasts a warning that infringers will be prosecuted.

Can the © be placed on the back of my picture, or must it appear on the front?

Section 401 (c) and House Report ML-182

Your copyright notice can be rubber-stamped, printed on a label or embedded in your digital files In the case of a transparency, it can be placed on the border (back or front). Be sure the © is enclosed in a circle, not just parentheses. Thanks to the Berne Convention, the copyright notice doesn’t even have to appear anywhere; nevertheless, place it on each of your photos to warn would-be infringers.

Who owns my picture?

Sections 201(a)(b)(c) and 203(a)(3)

You do, from the moment you click the shutter (“fix the image in a tangible form”). Before 1978 it was assumed the person you authorized to use your picture (publisher, ad agency, client) owned the copyright. The new law assumes that you own all the rights to your pictures, unless you have signed those rights away. Except in a case where you have entered into some kind of transfer-of-rights agreement in writing with a client or publisher, such as a work-for-hire agreement, no one else can exercise any ownership rights to your picture. Even if you do sell “all” rights to your picture, in thirty-five years, if you or your heirs take appropriate action, you can take the copyright back.

How long do I own the copyright on my photograph?

Sections 302(a) and 304(a)(b)

The 1976 Copyright Law says copyright in your picture “subsists from its creation” (when you click the shutter), and you own copyright to it for as long as you live, plus fifty years. The old law, by the way, allowed you only twenty-eight years to own your picture, plus a renewal period of twenty-eight years—for a total of fifty-six years. If you register, that renewal has been extended to forty-seven years, for a total of seventy-five years. If you don’t register your copyright in a pre-1976 work, you can’t renew it, and at the end of twenty-eight years it will fall into public domain. To register pictures that hold special importance for you, the current fee is twenty dollars. Ask for Form VA. If you wish to register nonphotographic work, such as writing, ask the Copyright Office for Form TX.

How can my picture fall into the public domain?

Sections 405 and 406

Publication without notice before 1978 meant your picture was in the public domain—that is, anyone could use it and not be required to pay you for it. From 1978 to March 1989, publication without proper notice put your picture in the public domain unless you took steps to “cure” the omission or defect. Under present law, you needn’t worry about your post-1989 photos falling into public domain until your copyright expires (your lifetime plus fifty years).

What is group registration, and how do I do it?

Section 408(c)(2)

This provision of the law says you can register any number of pictures published in one publication during one year for one price. Whether you’re registering five pictures or fifty, as long as they’re all in one magazine, newspaper or publication, the fee is currently only $30. (You can file group registrations of your published works for one filing fee if they are all created in the same year; if publication dates aren’t listed, all must be first published within three months of filing.)

How to do it: For each photo you choose, obtain one copy of the entire periodical in which it appeared. To group-register, fill out Forms VA and GR/CP (available from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20559, www.copyright.gov). Send to the Copyright Office the forms, your $30 fee (in check or money order payable to the Register of Copyrights), and copies of the periodicals or newspapers in which your published pictures appeared. (The U.S. Copyright Office has been a part of the Library of Congress since 1870.)

For unpublished pictures: Submit several contact-size pictures on one 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm) sheet, or submit photocopies of transparencies or black-and-white prints (photographic prints, not photocopies) of the pictures you wish to register. Since unpublished works must be in the form of a collection, title this collection of pictures “Collection of Photographs by [Your Name].” Fill this title in at space number 1 on Form VA. A handy way to group-register a collection of slides is to put twenty images in a plastic sleeve, photograph them in color on your light stand and then blow them up to 11" × 14" (28cm × 36cm). You also can submit printouts and CD-ROMs with your images. (For more detailed information on digital formats, check out the website of the Copyright Office, www.copyright.gov.) You can submit any number of multiple sets under one title, and the cost is $30 (at this writing).

Note: Because the Copyright Law is an ever-changing document, be sure to check for updates and/or changes with the Copyright Office from time to time.

If I ask a publisher to include my © notice alongside my picture when she publishes it, but the © is omitted, does this invalidate my copyright protection?

Sections 401(a)(c), 405(a)(2)(3), 407(a)(2) and 408(a)

No. Since March 1, 1989, no notice is required to preserve a copyright. For earlier work first published between January 1, 1978, and March 1, 1989, your copyright protection exists if you can show proof that your picture (1) was rubber-stamped, labeled, printed or handwritten with the copyright notice on the front or back before it was published, (2) was accompanied by a letter from you asking for publication of your notice with the photo in the publication, or (3) was published in a copyrighted publication. Since all of the pictures (except advertisements) in a publication are covered by the blanket copyright notice in the masthead, copyright protection for you was implied. However, make sure that the publication’s copyright notice was correct. (You’d be amazed at how many publications print partial—or erroneous—notices!)

Can I place the © notice on my slides and photographs and be protected even if I don’t register my photos with the Copyright Office?

Sections 401 (a)(c), 405(a)(2)(3), 407(a)(2) and 408(a)

Yes. The © notice you put on your picture is “official” and is free. It lets the world know that you own the copyright to your picture, but you don’t need the © notice for your picture to be protected. The revised Copyright Law recognizes you as copyright owner, with or without the © notice and with or without registering the photo. If a picture isn’t registered with the Copyright Office, that doesn’t mean it isn’t copyrighted. However, like your automobile, if it’s stolen, it’s a lot easier to prove it’s yours if it’s registered with the Department of Motor Vehicles. You have more immediate clout than if you can produce only your title to your car but no registration. Of course, the important reason to register any photos is so you can get attorneys’ fees and punitive awards (statutory damages in an infringement suit). In cases of your very special pictures, you may wish to have the extra clout that you would have against possible infringers if such pictures were registered.

If I don’t register my pictures, but I publish them anyway with the © notice, can I be ordered to send them in to the Copyright Office?

Sections 407(a)(d)(1)(2)(3) and 704 Title 44 (2901)

Yes. Under the 1978 system, a photographer will not be forced to register his pictures, but he can still be ordered to submit to the Library of Congress (the parent office of the Copyright Office) two copies of a published work in which a © notice appears. If, after being ordered to send them, the photographer does not do so within three months, he can be fined up to $250 (for each picture) for the first offense, plus the retail cost of acquiring the picture(s). If the photographer fails to or refuses to comply with the demand of the Copyright Office, an additional fine of $2,500 can be imposed. All deposited pictures become the property of the Library of Congress, but you retain the copyright, since copyright is distinct from ownership of any copy. Incidentally, if you register your work, the copies sent with the registration satisfy the deposit requirement—but the reverse is not true. Even if a work has been deposited, two additional copies must accompany any registration application.

What does “work for hire” mean?

Section 101(1)(2)

If you’re employed by a company and take a picture for that company as an employee, generally speaking, that’s work for hire. The company owns the picture. At some point, you may have signed a work-for-hire agreement with your employer. Even if you haven’t, and your work was done within the scope of your employment, total ownership of your pictures belongs to your employer. If you’re a freelancer and a picture is specifically commissioned or ordered by a company, and you have signed an agreement saying so, your photos may be works made for hire. However, if a magazine gives you an assignment and pays for your expenses, that is not working for hire unless you sign a document saying so. If you receive such an assignment, avoid signing a work-for-hire statement. Instead, agree to allow exclusive rights to the client for a limited time. If the client insists on all rights, increase your fee. A good test for work for hire is to ask, “If someone were to be sued regarding this, who would be liable—the photographer or the entity commissioning the photographer?” For an in-depth discussion on work for hire as it applies to publishing and multimedia development, consult the bibliography for Multimedia Law and Business Handbook by J. Dianne Brinson and Mark F. Radcliffe.

Are the pictures I submit to a photo editor who’s listed in Photographer’s Market or similar reference works considered works made for hire?

Sections 101(1) (2) and 201(b)

No, unless you have signed a work-for-hire letter, slip, form or statement. Remember, if the pictures existed before you made contact with the photo buyer, they were not “specifically ordered and commissioned” and cannot be works made for hire.

What if a magazine publisher wants to reprint my picture a second time as a reprint of the original article, wants to use my picture to advertise his publication, or wants to use my picture a second time in an anthology? Does the publisher have the right?

Section 201(c)

As a stock photographer, you should license only one-time publishing rights to a photo buyer. Unless something different is stipulated in writing, the law assumes that you have licensed your picture to the photo buyer only for use in the magazine, any revision of that magazine, or any subsequent edition of that same magazine issue—which could mean more than one use, but not in another publication or for a different usage. In no other case may the photo buyer presume to use your pictures without your consent and/or compensation to you. If a photo buyer would like your picture for additional use, refer to the pricing guide for photo reuse in Table 8-3 on page 123. Note: In the stock photo industry, we use the term photo buyer. This means that the buyer is buying certain rights (usually one-time rights), not the copyright, and not the physical black-and-white print, slide or digital image itself. These prints, slides and CDs, on a DVD, saved to a USB flash drive (or other digital media) usually are returned after the transaction. (Slides should always be returned.)

What penalties does infringement (unauthorized use of a photo illustration) call for?

Sections 412(1)(2), 205(d), 411 and 504

The owner of a registered copyrighted picture on which infringement has been proved may receive, in addition to the actual damages she has suffered (lost sales, for example), the amount in cash of the profits received by the infringer. If the copyright owner can prove the infringement was willful, she can receive as much as $100,000 for each infringement if she wins. However, if the infringer proves that he infringed innocently, the award to the copyright owner could be as low as $200 or less—even zero. If the copyright is registered within three months of publication, the copyright owner can receive statutory damages instead of lost profits. Thus, even if the infringer earned only $50, the award could be between $500 and $20,000. Legal fees also may be reimbursed but only if the copyright was registered within three months after publication or before the infringement occurred. If you don’t register your picture and it’s used without permission, you must register before you can go to court—and you may lose the right to statutory damages and attorneys’ fees by procrastinating in your registration.

However, other remedies, such as impoundment or injunction, are available and may be worth the cost of going to court for the satisfaction. In addition, the government occasionally will even prosecute an infringer. Criminal penalties include fines (of which you get no share; the government gets it all) and imprisonment.

What is the statute of limitations on infringement?

Section 507(a)(b)

If you don’t discover infringement within three years, you have no recourse for damages.

Can I take a picture of a photograph or an object that is copyrighted?

Sections 113(c) and 107

Yes. Under the “fair use” doctrine, a photograph or other copyrighted work can be copied or photographed for uses such as criticism, comment, teaching or research. The court is more likely to consider your use as “fair use” if you use it for a noncommercial purpose rather than a commercial purpose. For example, your one-time use of a copyrighted picture in a slide program for a nonprofit lecture series or camera club demonstration would likely be considered fair use. However, if you used the picture for self-promotion or advertising purposes, or if the picture was given such widespread distribution that it reduced the effective market value of the original copyrighted photograph or article, you would probably be guilty of infringement. As a stock photographer, if your pictures are used basically to educate and inform the public, taking a photograph of a copyrighted object or picture might not be infringement. However, one of the criteria for fair use is the amount of the work you reproduce. A photograph of someone else’s entire photo or painting might well be infringement. Of course, keep in mind that your interpretation might be different from that of the court, and consider each case in its own context.

For a more thorough discussion of fair use, see Copyright Office Circular 21 www.copyright.gov/circs/circ21.pdf, or consult chapter eleven in the Multimedia Law and Business Handbook listed in the bibliography.

How long can I wait to register a published picture?

Sections 104(a), 405, 406, 408(a) and 412(2)

Any length of time. Pictures registered within three months of first publication (or registered prior to publication) receive broader legal remedies than those registered later, and registration is the prerequisite for any suit. However, your copyright exists whether or not your picture is registered. If your pictures were published before March 1, 1989, and no copyright notice was applied to them, you had five years to register the pictures in order to correct the omission. If the copyright notice was erroneous (e.g., if your name or the date was incorrect), you may not be protected against those who rely on the information in the notice until you have registered.

If my picture is included in a magazine or book that’s copyrighted, does that mean the publication owns the copyright to my picture?

Section 201(c)

No, you own the copyright, unless you’ve made and signed some special arrangement with the publisher. If you’ve leased a picture on a one-time- rights basis, then it’s assumed that the publisher has only leased your picture for temporary use in that publication.

If I don’t have my picture registered and it’s included in a copyrighted publication without my copyright notice on it, am I protected by the blanket copyright of all the (editorial) material in the publication?

Section 201 (c)

You are protected in most cases. (See Morris v. Business Concepts, Inc.)

Are pictures used in advertising also covered by the blanket copyright notice on a copyrighted publication?

Section 404(a)

No. The publisher can claim copyright only on that material over which it has editorial authority. If your picture is used for advertising purposes, request that the advertising agency include your notice. Although the notice isn’t required, using it alongside your photo might result in additional sales.

What is the copyright status of all the pictures I published before the new law came into effect on January 1, 1978?

Section 408(c)(3)(c)

Under the old law, unless you registered and renewed those pictures, your pictures would have copyright protection limited to twenty-eight years. Renewal would have extended the protection to fifty-six years. Since 1978, works that are or have been renewed have their copyrights extended for a total of seventy-five years.

Prior to 1978, unless you had an agreement limiting the rights you were granting, or unless the publication reverted the rights to you after publication, copyright for the first twenty-eight years belonged to the publication as work made for hire.

Note: As mentioned, the Copyright Law is an ever-changing instrument. Great effort has been made to make this section as up-to-date as possible. This section is not designed to be a legal reference, however, and I recommend checking with the Copyright Office for the latest information.

Work for Hire

Although the Q and A forum touches on work for hire, you should know more about this subject, especially if you’ll be accepting an occasional service assignment that could fall into a work-for-hire situation.

Before 1978 the courts generally assumed that if a freelancer did a specific photographic job for a person or company, the photographer didn’t own the resulting pictures—the company or client owned them. The 1978 Copyright Law reverses this, and the courts assume the photographer owns the pictures, not the client. This alone clearly indicates the growing awareness of the resale value of stock photos.

The law now says that except for employees acting within the scope of their employment, unless there’s a written agreement signed by both parties stating the photographer’s work is work for hire, claims to ownership of the resulting pictures must be based on the rights (ranging from “one-time” to “all”) that you assign to the client.

A client could assume ownership of your pictures under the following circumstances:

- Your client is actually your employer, and you have made no provision to transfer copyright ownership of your pictures to yourself while under his employ. (Note: It’s possible to have the copyright of your pictures assigned to you after an agreed-upon time.) An employer owns the copyright in works created by an employee within the scope of employment.

- The client is not your employer but claims to be. In Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid (1989), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the tests for employment found in agency law apply to work for hire. These would include who paid for the supplies and equipment, whether you could hire assistants, where the work took place, whether the employer could order you to do additional work and whether you are in business.

- If you don’t fit these definitions of employee, a work for hire must meet three conditions: (1) It must be specially ordered and commissioned; (2) there must be an agreement in writing, signed by both parties, specifying that this is a work for hire; and (3) the work must fall into one of nine specific categories, such as contributions to a collective work or an atlas. For a more thorough discussion, see the Multimedia Law and Business Handbook.

At all costs, we as stock photographers should protect and defend our rights provided by the Copyright Law. We need to be ever vigilant. As an example, in 1985 the American Association of Advertising Agencies called for (but did not get) a return to the “traditional understanding” of the 1909 Copyright Law, which made the client, not the photographer, the presumed copyright owner. Work for hire in the present Copyright Law presumes that you own the copyright. Let’s keep it that way.

- A purchase order, assignment sheet or similar form that you have signed could state (sometimes in an ambiguous or roundabout way) that you’re assigning copyright of the work to the client. The statement might read, “All rights to photographs covered in this contract become the sole property of the client.” If you give away all rights, you give away your copyright. A work-made-for-hire agreement is effective only for eight types of specially commissioned works:

a. Contributions to collective works

b. Part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work (Many multimedia works, including CD-ROMs, are audiovisual works.)

c. Translations

d. Supplementary works (works prepared as adjuncts to other work)

e. Compilations

f. Instructional texts

g. Tests or answer material for tests

h. Atlases

- If you’ve endorsed a check that has printed on it a statement that says by endorsing the check you relinquish all claims to ownership of your pictures, you may be assigning all rights: “Endorsement below constitutes release of ownership of all rights to manuscripts, photographs, illustrations or drawings covered by this payment.” A statement after the fact that the work was made for hire might have the same effect. Your recourse here would depend on various circumstances. You might cross out the offending lines, initial, and endorse the check. You might send the check back, and ask the client to issue a new check minus the offending phrase. Each situation is different. If possible, consult with other photographers who have completed assignments for the same company, and compare notes on how arrangements with the client have been worked out.

In some cases, the client may be testing you. Handle with care. With diplomacy, you could get full copyright ownership and remain in the client’s good graces.

The work-for-hire provision of the Copyright Act of 1976 is a benefit to the stock photographer because it makes the assumption that the photographer owns the picture, not the client. If you find yourself in a game of politics in a service-photography situation and your client insists on “all rights” (that is, work for hire), ask the client this question: “If I were to be negligent and be sued, who would be liable—me or you?” The client might back off from insisting on all rights.

Electronic Rights

Treat electronic rights like you treat rights for printed media. Insist on having your name and the © symbol by all your images used electronically.

Do not allow publishers to use your images electronically without negotiating a separate usage with you. Many photographers, who have failed to read contracts before signing them, have discovered that some publishers now want print and electronic rights—often for the same fee that usually covered only print rights.

For more detailed information on this check my other book, sellphotos.com.

Which Usage Rights Do You Sell?

The title of this book is Sell & Re-Sell Your Photos. It should be Sell & Re-Sell the Rights to Your Photos. As a copyright owner, you have the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute and modify your photos.

You don’t want to sell all usage rights, as in a work-for-hire situation. You want to license your photos, granting people permission for specific usage rights. There are different sizes, shapes and extents of rights, but primarily you want to base your sales on one-time-use rights. Any other rights of use should require separate negotiation and additional payment.

Read the Fine Print

The different designations of usage rights commonly accepted are as follows:

One-Time Rights. The client or publication has permission to use the picture only once. You license the picture for that one use only.

First Rights. These are the same as one-time rights, except the client or publication pays a little more for the opportunity to be the first to publish your picture(s).

Exclusive Rights. The client or publication has exclusive rights to your photograph. This can be for a specified amount of time, such as one or two years. After that time, the rights return to you. Calendar companies often ask for exclusive rights. You also may limit this by territory or type of use (for example, North America, or calendar but not book use). Again, the client pays more for these rights.

Electronic Rights. You can arrange to lease your image on an exclusive-rights or an all-rights basis, for an appropriate fee just like for use in magazines, textbooks and calendars.

Reserved Rights. A client or publication may wish to pay you extra to be the only purchaser to have the privilege of using your picture in a particular manner—such as on a poster or as a bookmark—in which case you would reserve that use specifically for them.

All Rights. This is the outright assignment (transfer) of copyright to a client. After thirty-five years, if you wish the rights to the photo to return to you or to your heirs, you or your heirs have the right to reclaim them. Some photo buyers think they need “all rights” when they really don’t. Educating your clients is part of being in business.

As a stock photographer, you should avoid assigning all rights to a client or publication if the picture has marketing potential as a stock photograph. If the picture, however, is timely, it may be wiser to accept the substantial payment that an all-rights arrangement commands, and relinquish your rights to the picture. Examples of pictures that might soon become outdated, and therefore unsalable, are photos of sports events, festivals, and fairs.

World Rights. The client or publication is granted a license to use the photograph in international markets.

First-Edition Rights. You sell rights to only the first printing of a book, periodical and so on. After that, you negotiate for other editions.

Related Rights. These rights allow the use of a photo for related purposes, such as advertising and promotional use.

Specific Rights. Certain individualized rights are outlined and granted.

Your standard cover letter (see Figure 9-1 on page 138) can serve as an invoice to your photo buyer. In some cases, however, you will come to an agreement with a buyer regarding certain other rights and/or arrangements that are not covered by your standard letter. Spell out these terms in a separate letter to the buyer confirming the understandings. Also send an invoice with your shipment that reiterates all of the pertinent details of the transaction, such as rights being offered, number of pictures, and each picture’s identification number, size, type (color or black and white), date and so on. Invoices are available at stationery stores. Professional-looking invoices are available from your local printer and office supply stores like OfficeMax/Office Depot (www.officedepot.com), and Staples (www.staples.com). If you’re computerized, you can prepare your own invoices. Just be sure to use quality stationery.

Forms to Protect Your Rights

Up to this point, we’ve been discussing the rights of photo usage that you sell. What about your rights with regard to damage, loss or pictures being held for lengthy periods of time? Your photomarketing endeavor necessitates submitting valuable photographic materials to persons with whom you’ve never had personal contact. Is this taking a risk?

Is it a risk to travel down a road at 55 mph and face the oncoming traffic on the other side of the road? Any one of those cars could cross over into your lane. What makes you continually take this risk?

You take it because the benefits of driving your car outweigh the risks involved.

Likewise, you’re going to have to put a lot of faith in the honesty of the photo buyers you’re dealing with. You’re continually going to have to risk damage or loss to reap the benefits of getting wide exposure for your pictures.

There are contract forms available—also called “Terms and Conditions” agreements—that a photographer can issue to a photo buyer to specify terms of compensation in the event of damage or loss of photos while in the hands of the photo buyer or his company, agents and so on. However, newcomers (or sometimes anyone—veteran or neophyte) have little chance of getting a photo buyer to sign a “Terms and Conditions” agreement. The disadvantages to the buyer outweigh the potential benefits. In fact, he might turn the tables and ask you to sign an indemnification statement that will free him of any liability as a consequence of using your pictures.

Keep in mind that others you depend on to handle your prints and transparencies—the U.S. Postal Service, FedEx, UPS and your film processor—refuse to reimburse you more than “the actual cost of a similar amount of unexposed film” in the event of damage or loss. Also, the IRS, in assessing the depreciation of your slide inventory, sets the value not at intrinsic value, but only at actual cost.

My advice: If you’re an entry-level editorial stock photographer, lay out your terms and conditions to a photo buyer in a friendly, easy-to-understand cover letter, as shown in Figure 9-1 on page 138. Once you attain stature in your stock photo operation, if you wish—or in special instances—you can test the waters by submitting a formal “Terms and Conditions” statement. This kind of statement, however, might intimidate, turn off or actually anger a publisher unless presented by a “name” photographer. Politics is involved, of course, and you’ll have to judge how to handle each situation on an individual basis.

Even a “name” photographer will think twice before using these agreements, however. For example, such agreements usually include a provision that calls for reimbursement of $1,500 for each transparency lost or damaged. This fee has indeed been collected, but subsequent communication between photo buyer and photographer is usually not quite the same, if it exists at all. If you find yourself in a similar situation, you will probably want to weigh your loss against your relationship with the photo buyer, and determine whether you wish to press such a payment from a good client for the result of an unusual accident or an honest mistake. The photo buyers who seem to make 90 percent of the mistakes in this industry are those who are new in the field. A good rule: Don’t deal with a photo buyer or publisher unless she has a track record of three years, minimum.

If you wish to research these forms further, particularly as an aid in dealings with clients or companies you’re not familiar with or whose proven track records are questionable, ASMP Professional Business Practices in Photography (includes tear-out sample forms) offers sound examples. It’s listed in the bibliography.

Legal Help

If you need legal help in dealing with a photo buyer, a publisher or the IRS, the two organizations below might offer assistance. To consult with just any attorney on a legal problem concerning the arts and publication is like offering him a blank check to finance his education in the matter. Different attorneys are well versed in some areas, less informed in others. Before you contact an attorney, check with Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts (VLA). The organization includes more than 800 volunteer attorneys across the nation who handle a variety of arts-related situations. For more information and a directory of VLA offices nationwide, contact the New York office: 1 East Fifty-third Street, Sixth Floor, New York, New York 10022; (212) 319-2787, ext. 1; www.vlany.org. In some cases the consultations are free. In other cases, there are predicted fees, but at least you’ll know that the VLA attorneys have good track records in dealing in the area of intellectual properties.

A helpful organization for copyright help is Editorial Photographers (EP) www.editorialphoto.com.

You Will Rarely Need a Model Release for Editorial Use

There is perhaps no area of photography more fraught with controversy and misconception among equally competent experts than the issue of when model releases are required.

Photographers are confused and, as a result, often hesitate to take or use a picture because model releases will be too difficult to obtain. This uncertainty seriously limits the photographer, and in the end it limits you and me—the public.

The Constitution is brief and open to interpretation when, in the First Amendment, it affords us freedom of the press. Freedoms are sometimes abused, and court cases over the years have attempted to interpret and clarify our freedom to photograph. New York State courts have tried many cases over the years. As a consequence, many of the other forty-nine states tend to look toward New York statutes and precedents for guidance. The current spirit of the interpretation of the First Amendment is that we, the public, relinquish our right to be informed if we succumb to a requirement of blanket model releases for everything photographed. If a photograph is used to inform or to educate, a model release is not required.

What are other books saying about model-release requirements?

It has long been established that photographs reproduced in the editorial portions of a magazine, book or newspaper do not require model releases for recognizable people. Under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, photographs may be used without releases if they are not libelous, if they relate to the subject they illustrate, or if the captions are related properly to the pictures, and if they are used to inform or educate. These provisions are confined to photographs used for non-advertising and non-commercial purposes.

—from Amphoto Guide to Selling Photographs: Rates

and Rights,

by Lou Jacobs Jr. (Amphoto Books, page 174)

Can you include bystanders in the photographs of the parade when the article is published? Yes, you can, and you don’t need a release. This is because the parade is newsworthy. When someone joins in a public event, he or she gives up some of the right of privacy.

—from Selling Your Photography: The Complete Marketing, Business and Legal Guide,

by Arie Kopelman and Tad Crawford

(St. Martin’s Press, page 194)

Most of your publishing markets are well aware of the fact that they seldom need model releases. In my own case, I started out getting model releases whenever I shot, which hampered my photography in the process. Once I learned that publishers for the most part take their First Amendment rights seriously and do not require model releases (with the exception of specific instances, which I’ll discuss in a moment), I stopped getting written releases and haven’t gotten any for twenty-some years. (That’s one of the advantages of being an editorial stock photographer and not a commercial photographer.) My model-release file gathers dust in a far corner of my office, and my deposit slips continue to travel to the bank with regularity.

In the course of my photomarketing career, I’ve come across publishers now and then (or photo buyers new to the job) who were unaware of their First Amendment rights or were unwittingly surrendering them. If they persist in requiring model releases when they’re not necessary, I drop them from my Market List.

Model Releases—When Must You Get Them?

Your photo illustrations are used to inform and to educate. That’s why your photo buyers will rarely require a model release. Just when are you likely to need one?

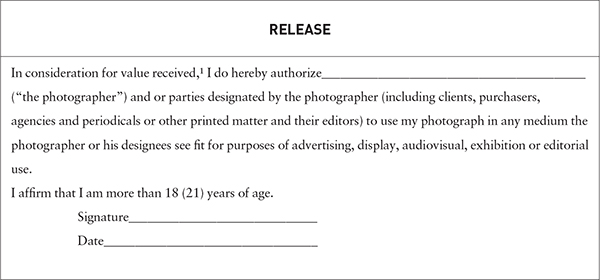

Figure 15-2. Model release.

Figure 15-3. Guardian’s consent for model release.

Some gray areas have developed over the years, and these instances are the exceptions to the rule. Pictures that might shock what’s defined as the normal sensibilities of ordinary people may be categorized as outside the “inform or educate” interpretation. Some other sensitive areas include mental illness, crime, family or personal strife, chemical dependency, mental retardation, medicine, religion, teen pregnancy and sex education. Each case has to be interpreted in its own context. For example, a court case involving sex education might be treated differently in Mississippi than it would in California. Take local and regional taboos into consideration when you publish your photos.

A model release might be required by the publisher of an industry-sponsored magazine because of implied endorsement. If a picture of you, for example, were to appear on the cover of World Travel Magazine, it might imply that you, indeed, agree that Northwest Airlines “knows how to fly.”

As mentioned earlier, model releases usually are required in service photography. If a picture of you or your son or daughter is published in a commercial way and a trade benefit is implied, you or your son or daughter should have the right to give permission for such use, on one hand, and should receive compensation for such use, on the other.

Stock photo agencies sell pictures for both editorial and commercial use, and while they frequently do not require model releases when your pictures are submitted, they will want to know if releases are available. Being in a position to say to an agency, “MRA” (Model Release Available), will make your pictures more salable.

Oral Releases

Written model releases are required in New York State, but oral releases are valid in most other states. This means you can verbally ask permission for “release” from the person you photograph. This is to avoid later misunderstanding even though the way your picture is used might not even require a model release. You can say, for example, “Is it okay if I include this picture in my photography files for possible use in magazines or books?” Keep in mind that, should it ever come to court, verbal agreements are much harder to prove.

However, if you’re also a commercial stock photographer and there’s a chance the picture may be used for commercial purposes, it’s advisable to make your verbal request more encompassing: “If I send you a copy of this picture as payment, would you allow me to include this picture in my files for possible use in advertising and promotion?”

When you read about lawsuits involving the misuse of photographs by photographers, it’s usually a commercial stock photographer who has used a photograph of a person in a manner different from what the model expected. If you’re a commercial stock photographer, don’t rely on a verbal model release. Get a signed release. Spell out exactly how the picture will be used. If the person is under eighteen years of age, obtain a release from a parent or guardian. If the property you’re photographing also capitalizes on its notoriety, and you plan to use the photo for commercial use, then get a “property” release. You’ll find that in most such situations, the property owner will be happy to sign a property release; in effect, you’re serving as a free public relations or publicity agent, who normally might cost the owner seventy-five dollars or more an hour.

How do you learn if oral model releases are acceptable in your state? Almost every county in the United States has a law library at the county courthouse. Consult the current volumes of state statutes for the laws on invasion of privacy. Ask the law librarian or the county attorney to assist you. For details on cases involving invasion of privacy, consult the volumes entitled “Case Index” or the equivalent. You’ll be pleasantly surprised to learn that few cases are recorded.

If you’re unable to visit the law library in person, try phoning. Let the librarian know if you’re not familiar with the terms or descriptions. An expert will be more helpful and willing to refer you to additional sources of information if you let her control the conversation.

Many photographers shoot the pictures that they plan to send to an agency, or that might be used from their own files for commercial purposes, within a close geographical area. They can then easily go back later and obtain a written model release, when necessary. Another route is to work with one or several neighboring families and get a blanket model release for the entire family, then barter family portraits over the years in return for the privilege of photographing family members from time to time for your stock files.

Figure 15-2 shows an example of an acceptable model release. Figure 15-3 shows a release for parents and guardians to sign for models under eighteen years old (under twenty-one in some states). These two releases have each been designed to fit onto a pocket-size 3" × 5" (8cm × 13cm) pad.

Can We Save Them Both? The Right of Privacy and Our First Amendment Rights

The rights safeguarded by our Constitution include the right of privacy—our individual right to decide whether we want our peace interrupted. Occasionally a photographer violates normal courtesies, laws and decency with her picture-taking. Such instances are, of course, exceptions, and all are answerable within the law.

However, we’ve seen instances in which individuals engaged in medical quackery and leaders of political groups, militia groups or religious cults will commit their misdeeds against society and then attempt to take refuge in our right-of-privacy laws. Usually, prominent public figures must surrender such privacy and open themselves to public scrutiny. Such is the price of glory.

One state, Tennessee, has passed a law (“The Personal Rights Protection Act of 1984”) that is a bureaucrat’s and politician’s dream. It states that publishers in Tennessee cannot use photos featuring people if the photographer has not obtained a model release. This means freelancers cannot photograph police brutality, school system wrongdoings, militia activities, highway accidents, city hall personalities, religious rites and so on. Our First Amendment recognized that the curtailment of information to the public invites corruption.

What about the nonpublic figure, the person who is just going about his normal business? Invasion of privacy is not so much a question of whether or not you should take a picture or not, but whether or not the publisher should publish it and in what context.

While our Constitution allows us freedom of the press, it also allows us freedom from intrusion on our privacy. Herein lies a conflict, and the courts are left to decide whether a photographer committed invasion of privacy in any individual instance.

Instances usually considered invasion of privacy would occur if you were to do the following:

- Trespass on a person’s property and photograph him or members of his family without valid reason (in connection with a newsworthy event generally would be a valid reason).

- Embarrass someone publicly by disclosing private facts about him through your published photographs.

- Publish a person’s picture (without permission) in a manner that implies something that is not true.

- Use the person’s picture or name (without permission) for commercial purposes.

There have been very few cases in U.S. court history involving a photographer with invasion of privacy. Except for number one above, invasion of privacy usually deals with how a picture is used, not the actual taking of the picture. When in doubt, rely on the Golden Rule:

- Service photographers, take note. Since noneditorial photographs (ads) are not protected by the blanket copyright, insist that your copyright notice (unless you worked “for hire”) be included with your picture.

- If the purchase order or agreement—or even the check—you receive from your client requires you to sign anything that implies that you’re offering more than one-time publishing rights, or states a work-for-hire arrangement, don’t sign it. Cross out and initial that portion of the purchase agreement, place your rubber stamp on the margin, send it with the picture (also stamped), and let your client carry the ball from there.

- Random published photographs, under this system, are arbitrarily requested for deposit by researchers at the Copyright Office. By the way, I haven’t heard of any cases where someone was fined $250, or $2,500, for not submitting the requested pictures.