13

Keeping Records: Knowing Where Everything Is

THE LAZY PERSON’S WAY TO EXTRA SALES—KNOWING WHAT’S SELLING

Note: This chapter was written by Rohn Engh. I, Mike, have added the last section about digital. The system Rohn worked with still works but as with any system, make sure you find something that fits your needs.

I’m lazy at heart. I like to put the lawn rake back when I’m done with it because I’ve learned if I don’t, it’s a lot more work next time to search for it, and possibly not even find it when I need it.

This lazy kind of thinking got me into a very good habit after a while. By having (or finding) a place for everything here at the office, I got into the habit of putting everything away.

I take the same approach to filing computer discs, slides and color and black-and-white prints. If something’s worth having, I figure, it’s worth knowing where it is when you need it.

I was happily spurred along in this principle when I inherited several hundred used file folders from a businessman who was retiring. By using a separate folder for each separate photo illustration, I could note right on the folder whenever a picture sold. For black-and-whites or color negatives, I put a matching contact print on each folder, thus giving myself an immediate visual reminder of what was selling.

After a few years, my record-keeping system was teaching me what pictures sold best and therefore, which pictures I should take more of. By continually supplying my Market List’s buyers with the kind of pictures they needed, I survived as a stock photographer.

File It! How to Avoid Excessive Record Keeping

This record-keeping system also extends to my everyday office activities.

One method I use to minimize record keeping is to put new projects into a mini-file rather than into the central files. I find that I usually complete mini-projects in about a year. Researching for and purchasing a new computer network was a mini-project, so was remodeling our office in the barn. Other mini-projects revolve around collecting material for future photo stories or photo essays.

Here’s a simple technique for a mini-file. The essential ingredients: two sets of two indexes numbered 1 through 24 and lettered A to Z; a temporary portable open file cabinet (like a box), usually made of pressed cardboard or metal and available at stationery stores; and two sheets of 81⁄2" × 11" (22cm × 28cm) paper, one numbered in two columns from 1 through 24 and the other set up in two columns from A through Z.

Let’s say you’re compiling some research on CD-ROM stock photography disc producers. Each entry is given a numerical designation, filed numerically and entered on the number sheet. The category also is cross-referenced by title and subject on the alphabetical sheet, with its numbered designation under the appropriate alphabet letter. The alphabetical listing also allows you to cross-reference the subject of the project or category. For example, if a Corel stock photo disc advertisement that you’ve torn from a magazine is filed under the number 34 (that’s the numerical designation for Corel Corporation in your filing system) and it contains three categories (birds, reptiles and horses), you would list those three categories on the alphabetical list and designate 34 as the file folder you could find those categories in.

Since the file box is small and portable, you can carry it between home and office or store it in a regular file drawer. I often have six or seven projects going at one time, with information building in twelve to fifteen others, and the mini-file system aids me in being a lazy shopkeeper. I never have to work at finding anything. When the project is completed, the file either earns a spot on my central files or is tossed away.

Knowing How to Put Your Finger on It: Cataloging Your Black and Whites and Transparencies

No cataloging system is better than the keywords it utilizes for its search function. Make sure your keywords are accurate. In the long run this will be well worth it. For example, in the future, stock photographers will make their keyword database available to certain photo buyers or search engines for highly specialized images. A sale or no sale might be the result of what kind of attention you give to proper keywording.

Many different software systems are available, and we’ll touch on all of them from the simplest to the more advanced. Picking a system is often a matter of personal preference, but it’s crucial for you to keep in mind that changing systems down the road is a lot of work. Take time to pick the system that’s right for you.

Software products change constantly. Thus, as you review the guides to software catalog systems in this chapter, think of them as rough guides only. Before you decide on any software for your cataloging needs, check with the manufacturer to make certain the current version is what you need.

Now then, do you need to be computerized to be able to catalog your images? Absolutely not. Even though cataloging software is a wonderful help—especially as your photo file grows—it’s not a necessity.

The Basics

A cataloging system should make it easy for you to find a specific photograph. The system also should let you quickly and accurately search for photographs in particular categories in your files. You want a system that’s easily expandable, versatile and able to handle a large amount of entries so that you can keep on using it as your files grow.

The Systems

The two main elements in any cataloging software are ease of data entry and ease of data retrieval (search). It should be easy for you to enter data about your photographs into the system, and it should be easy for you to search the system to find the photographs you’re looking for.

Choose a known, reliable software company to have the best chance for having support and upgrades available in the future. Over the years I have seen at least a dozen cataloging software companies go out of business—leaving their customers stranded.

The most basic of the computerized systems actually is not a software system in the true meaning of the word. This system will cost you little money, you will not need any special software, and you’ll be able to start right away. I’m talking about the easiest and simplest of them all: the “Do It Yourself” (DIY) system. Before I go into the various software systems made specifically for cataloging photographs, I’ll explain how you can set up a simple DIY system that can get you started right away.

DIY SYSTEM

This system assumes that you have a computer, a printer and some basic word-processing software like Microsoft Word, Corel WordPerfect or something similar. You need to make sure that you can use your word-processing software to make labels. In Word, check under the “Tools” header, and in WordPerfect, check under “Format.” At www.avery.com or at your local office supply store look for Avery Return Address Labels #8167 or #8667, 1⁄2" × 3⁄4" (13mm × 19mm), the perfect size for use on slide mounts. Each package will cost you approximately $13 (at this writing). There are twenty-five sheets in a package and eighty labels per sheet, making two thousand labels. Cost per label is $0.0065.

For ease of use and readability, use two labels per slide mount. One label should have a copyright symbol, your name and your contact information. Here is where it’s crucial that you plan ahead. Unless you know for sure that you will not move, change phone numbers or change your e-mail address in the next ten years, limit the contact information you put on these labels. Instead of putting your home phone, consider getting an 800 number that can move with you. Most phone carriers offer inexpensive 800 residential number services.

The second label should carry the identification number and the caption for the individual photographs. This label will change from photograph to photograph.

The next step is to figure out how you want your identification number system to work. Say that you photograph pure-breed dogs. One way you could organize the system is to give each breed its own number: German Shepherd is #01, Belgian Malanois is #02, Bernese Mountain Dog is #03 and so on. Then arrange all photographs of German Shepherds and catalog them in whatever order you want starting with Photo #01-0001; the next one will be #01-0002 and so on. Your photos of Belgian Malanois would be #02-0001, #02-0002, #02-0003 and so on.

You can keep your cataloged slides in slide sleeves in metal or cardboard filing cabinets, hanging file folders or three-ring binders. The most popular among stock photographers seem to be the larger binders with D-shaped rings, which will hold around 1,000 slides per binder.

You can adapt this system to prints as well. Instead of two labels per slide, use one (bigger) label, one per print, on the back.

THE SOFTWARE SYSTEMS

If you don’t feel like building your own system, or if you need something a little bit more advanced, a software cataloging/database product might be right for you.

Existing software products vary in price, from under $75 for a basic system without many frills, to several hundred dollars or more for a high-end system that offers image tracking, delivery memos, invoicing capabilities, bar coding and so on.

Again, software products come and go, and you should make sure to buy a reliable system that has promise to be around for a long time in case you need to expand and/or upgrade in the future.

Some products with solid reputations in the business that I feel comfortable recommending are: Proslide II—distributed by Ellenco (www.proslide.ipower.com); StockView 6 and InView—distributed by HindSight Ltd. (www.hsltd.us); PhotoLibrary—distributed by PKZ Software (www.pkzsoftware.com); FileMaker Pro—distributed by FileMaker Inc. (www.filemaker.com).

Remember that you want a system that can grow with you and a system that you feel comfortable working with. Most of the software products mentioned here have free demo versions on their websites available for downloading. It’s not a bad idea to test-drive the demo version of many different products before you decide what to purchase.

If you belong to a camera club, ask fellow members who are working stock photographers what product they would recommend. Best bets are those who have used their software for at least three years.

Counting the Beans

Knowing where the dollars are coming from and how many are staying at home is an important part of your operation. By not having an accounting system, you could be pouring dollars into the wrong area of marketing. Bad business decisions usually come from faulty information.

At an office supply store, you can buy an accounting ledger that you can tailor to your needs. If you’re computerized, you can start with an accounting program such as Quicken (www.quicken.com). We did this originally and have since upgraded to the networked version. Other good accounting software products are Intuit’s QuickBooks and Quicken Deluxe (www.intuit.com) and Peachtree Accounting (www.peachtree.com).

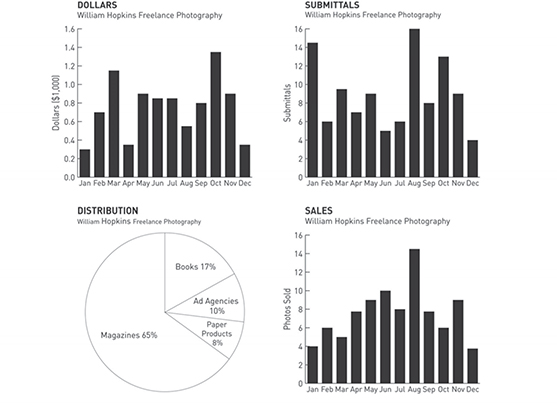

Photographer William Hopkins uses a simple graphics program to chart progress. He tracks the number of submissions he makes and then charts the number of photos sold and dollars that come in. He puts these figures together in a pie chart (see Table 13-1).

More Than Just a Portrait

Cute animal photos are typically used in decor photography, but if you add people in the mix a slew of new opportunities come knocking on the door. Instead of just another portrait of a cute Bernese Mountain Dog, take the dog to the vet. Instead of just a paw or just the tool by itself, put it all together and you get a photo of a dog having his claws trimmed.

Everything Has Its Place

We’ve all seen cartoons picturing busy editors, their desks piled high with paper. The caption usually quotes the editor defending her “filing” system.

You can’t afford the luxury of an editor’s haphazard filing system. As your stock photo library grows, so will your need to be able to locate everything, from addresses to contact sheets, negatives to notes.

Keep in control. If everything has its place, nothing should get lost. If you use an item, put it back when you’re finished. In contrast, the editor’s desk got that way because she didn’t follow these two principles:

- Make a place for it.

- Put it back in its place when you’re finished.

|

Is the editor lazy? To the contrary. It takes a lot more work to shuffle through that heap on her desk to locate something.

Time lost can mean lost sales for the stock photographer. Take the lazy person’s approach—know where everything is.

Protecting Your Files

Humidity is the greatest enemy of your transparencies (and sometimes of your prints). For $10 you can buy a humidistat (from the hardware store) to place near your storage area; it should read between 55° and 58° F (13° and 14° C). If the reading is lower, you’ll need a humidifier; if it’s higher, a dehumidifier. Moisture settles to the lower part of a room. Depending on the area of the country you live in, store your negatives and transparencies accordingly.

Damage from fire, smoke or water can put you out of business. Locate your backup discs, negatives and transparencies near an exit with easy access. If you live in a flood-prone area, store your film as high as possible.

Excessive temperatures also will damage your transparencies and negatives. Store them where the range of temperature is between 60°–80° F (16°–27° C).

Digital Storage

Do yourself a big favor and add captions to your high-resolution digital files. When you select cataloguing software, find one that allows you to search keywords and captions. This will help immensely when you need to find specific images.

Back up your digital files often, preferably in at least three different places using removable hard drives. I keep one in my office, one in a fire-retardant safe in the basement and one in a safety deposit box at my bank. But a back-up system is only as good as the practical usage it is put through, and you want to find a way that works for you and that is simple enough that you will actually make the backups as frequently as you need in your specific situation. I try to back up my high-resolution files after each shoot but I have to admit that I sometimes fail. I also use automatic backup software on all my computers as an added safety should something happen to the hard drives.

I’m often asked if I recommend solid external hard drives as opposed to the traditional kind with moving parts. Personally I use both (at the time of writing this). Solid drives have the benefit of no moving parts and hence there are fewer things that potentially can go wrong with them compared to traditional drives. This is why I’m moving towards using all solid drives.

For me, Adobe Photoshop Lightroom is my go-to software for both processing my RAW files (see chapter seventeen for more information about this) and cataloguing my photographs. It does everything I need and want it to do and suits my situation and me. Most software allows you to download a trial version these days. Do a search for photo cataloguing software and try out a few different ones until you find something that works for you and your specific situation.