Nobody knows what to call new media. Lots of people have tried to come up with just the right words.1

• Broadcasting & Cable adopted “Telemedia” as a weekly section heading.

• Advertising Age simply called their new media section “Interactive.”

• Wired suggested the phrases “alternative media” and “Internet media.” They seemed very old-fashioned and not up to Wired’s pithy style.

• The most-wired of Wired’s writers, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of MIT’s Media Lab, called it, simply, “multimedia.”

• “Merging” and “converging” were the favorite words during the waning years of the 1990s when things were, indeed, merging and converging. I use those words more often than the others.

To “merging” and “converging,” I add “emerging.” I like that it rhymes. But, more importantly, it also has meaning: “emerging” covers media that we haven’t quite finished inventing, the ones that synthesize “old” media and morph ideas into new ones. Each seems to create its own starting point.

A good example of morphed media is MSNBC, the marriage of “old” NBC and “new” Microsoft Network (MSN). (See Figure 9–1). The media kit I received from them shows not only information about the programming on the MSNBC cable channel and a profile of the channel’s viewers (very upscale) but also a Microsoft Network CD-ROM and a free one-month trial on MSN.

MSNBC Interactive (www.msnbc.com) differs from other “brand extension” Web sites in that it’s not repackaged material from the major network but in-depth enhancements of the content on the MSNBC cable channel. “Converging” fits MSNBC perfectly, given the combination of NBC-TV, that network’s affiliated stations, CNBC Cable, MSNBC Cable, and msnbc.com online. (See Figure 9–2.) The television network also maintained a Web content provider called “Interactive Neighborhood” for its affiliated stations.

Is there a definition for “new media”? This one is from the Direct Marketing Association’s 1996 study “Marketing in the Interactive Age”:

Any electronic, interactive communications media that allow the user to request or receive delivery of information, entertainment, marketing materials, products, and services.

FIGURE 9-1 “Merging” and “converging” were among the first words you read in this book and one of the backdrops to selling electronic media of any kind. “Converging” fits MSNBC perfectly, although they prefer “emerging.” Courtesy of NBC Cable Networks, Ad Sales Department, April 1998. ©1998, NBC Cable Networks.

New media are generally accepted quickly by early adopters who want to be the first with the latest. Then the new media spread slowly through the population, although “slowly” is not a word that really fits with merging, converging, and emerging new media.

Internet technology expanded so quickly that people began talking about “Web years” the same way they would about “dog years.” The Wall Street Journal interactive edition celebrated its first birthday with artwork of a cake and a single candle. The headline said “Thanks for the First Seven Years (Web Years, That Is).” The newsletter iRADIO said on its masthead: “Since 1995 (that’s 30 in Net years).”

That perception distracts us from the fact that even the newest media have history. The timeline is not as long or as deep as the histories of advertising, radio, and video, but there is history.

The explosive growth of the Internet since 1995 belies its beginnings in 1969 when the Pentagon established it to link government and university computers. At first, the Internet simply reserved phone lines for joint research projects. In 1975, the National Science Foundation took over maintenance of the Internet. When funding ended in 1995, there was a rush to add commercial entities to the World Wide Web to maintain the worldwide connections. Commercial users of the Internet were the new source of funding.

Paralleling the Internet’s quiet academic beginnings was the growth of interactive multimedia.2 It began with the Pong video arcade game, introduced in 1972. That’s the Stone Age in digital terms. More sophisticated games followed. Atari’s “Demon Attack” sold 2.6 million copies after its introduction in 1977. It was played on a $200 unit categorized as “a toy.”

FIGURE 9-2 MSNBC combines the resources of its parent, NBC-TV, its sister cable network, CNBC, and its online presence at www.msnbc.com to give us a perfect metaphor for converging media. Courtesy of NBC Cable Networks, Ad Sales Department, April 1998. ©1998, NBC Cable Networks.

The years after Pong saw remarkable advances in digital multimedia: the Apple II with floppy drive (1978), the IBM PC with Microsoft’s DOS (1981), the Macintosh (1984), Windows 1.0 (remarkable for 1985, but the digerati chose DOS), the Commodore Amiga computer (1986), and Harvard Graphics (1986).

The 1990s accelerated the pace of discovery of new ways to manipulate images, twist text, and connect ourselves with ever faster, ever more dazzling technology.

In a promotion for its annual convention and technical exhibition, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) in 1998 suggested that we were “living in the interactive interim.” That’s a very apt phrase that conjures what the NAB called “the Digital Halfway House—halfway between PC-TVs and TV-PCs, halfway between waveforms and bitstreams, halfway between Milton Berle and Virtual Vanna. …”

“With digital TV, you’re not just a viewer anymore, you’re part of the action,” said an ad for Canal + Technologies’ set-top box called Mediahighway. (See Figures 9-3 and 9-4.) Touting that 2 million European households had already gone digital, Canal + showed its wares at the same NAB convention. The theme of the gathering that year was “The Convergence Marketplace.”

Research by Arbitron revealed that more than one-third of TV households in the United States had an interest in using their TV sets for some PC functions. A third of TV households said they’d like to use such a system for e-mail. A quarter said they’d like to do shopping online. Another quarter said they’d order tickets online.7

Plain old news and information were the leading reasons consumers went online, according to a study by Market Facts for Advertising Age. The magazine noted in its 1996 report of the study: “[C]yber experts said entertainment would drive the nation to the information superhighway… but people are logging on for information, communication, and research much more than for entertainment.”

In the 1998 study, the numbers of Net users seeking information was up, not down. Advertising Age said one of the key online activities is searching for product information on company home pages.3

Of those respondents who had been online in the 6 months before the 1998 study, 91.2% said they were there to gather news and information (up from 82.0% in 1996), 88.2% used e-mail, 79.4% conducted research, and 68.5% surfed various sites. The percentages of users who were surfing, playing games, or joining online chat sessions was down in 1998 compared to the two previous years.

Newspapers were an early staple on the World Wide Web, probably to attract some of the cachet of electronic media for the oldest commercial medium. The New York Times on the Web created a database of 1.7 million registrants in order to customize advertising messages to online users.4 Some Web sites might as well be print, considering all the information they provide. Publishing on the Web is a cost-efficient way to distribute information.

A step above the publishing site is the self-service site where customers can do things for themselves, like check their bank balances or trace a FedEx package. The third step up is transaction-based and fully interactive, the real payoff for online users. IBM summed it up in a headline for its e-business services:

What’s the Difference Between a Little Kid with a Web Site and a Major Corporation with One? Nothing. That’s the Problem.5

I kept a copy of the Kiplinger Washington Letter from 1995 that asked the question, “Who runs the Internet?” The answer amused me: “No one in particular.”6 In fact, we all do. That’s why there’s a frenzied rush for Internet presence by huge corporations and by 8-year-olds, too.

Internet use at the time that study was released (1998) was just ahead of where TV usage stood in 1969, but online activity was growing at an exponential rate. Simmons Market Research in 1997 showed Internet penetration at 20% of American households, up from 12.5% in only 2 years’ time. Advertising Age’s sixth annual Interactive Media Study conducted in 1998 showed that 44.7% of a national sample had used the Internet. That compared with 30.2% the previous year.

“I was absolutely stunned by the increase in online usage,” says Tom Mularz, vice president and general manager of Market Facts, the company that conducted the Advertising Age study. He said that the increase in online usage was the largest year-to-year increase since the research company started doing the survey in 1993.

The U.S. Department of Commerce reported in April, 1998, that online traffic was doubling every 100 days and that electronic commerce would likely reach $300 billion by 2002.8 More than 100 million people were online, and the digital economy was growing at double the overall economy, representing more than 8% of the gross domestic product.

The Morgan Stanley publication, The Internet Advertising Report, which I quoted in Chapter 1, was also used in the Commerce Department data: radio took 30 years to reach an audience of 50 million; television took 13 years. The Internet took just four years.

Who knew it would grow that fast?

FIGURE 9-3 Is it a TV or is it a PC? This one’s a TV, and that’s all.

Nicholas Negroponte did. He predicted at a meeting of Internet founders in 1994 that there would be one billion Internet users worldwide by 2000. His audience laughed or rolled their eyes. “Those who knew the most about the Net were the most conservative,” he said.9

There was debate in the late 1990s about whether the World Wide Web was cutting into TV viewing levels. For the Web to be the villain to television, said a study by J. Walter Thompson advertising, medium and heavy users of TV would have to change their behavior drastically. It could happen, if there were compelling content to lure them away.

It happened in Fall 1997. Nielsen Media Research reviewed its people meter panel from the October TV sweeps and found a decline in TV viewing in Internet households in certain dayparts. From 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Internet households in Nielsen’s sample watched 25% less television than the total TV universe.10

Networks that showed affinity for the Internet (ABC, Fox, NBC, and WB) had higher ratings in Internet households than in the TV universe generally. Could the marriage of TV and the Web be far behind? NewMedia thinks that time will come:

FIGURE 9-4 TV or PC? The answer is “yes.” This advertisement for Canal + Technologies’ Mediahighway System is a perfect metaphor for merging, converging, and emerging new media. Mediahighway is a trademark of Canal +. The ads are used with permission.

Someday, an online Lucy Ricardo will send the planet into hysterics with her wacky, interactive hijinks; a cyberspace Johnny Carson will colonize a corner of the American evening; and a Net-bred Ted Koppel will make presidential candidates squirm with his laserlike questions—fed to him in real time by a nation of plugged-in voters.11

This paragraph was the preface for an article called “The Web’s Fall Season,” an overview of the pioneering efforts of interactive producers who hoped to make a mark in cyberspace. America Online and Microsoft Network hunted for new ideas from multimedia developers working on shoestring budgets. Smaller players like WebTV and C/NET were going Hollywood with the big guys. Traditional entertainment companies—HBO and Sony Pictures were cited in the article—hoped to take their TV and movie business interactive.

A dilemma arose: how to provide programming that satisfies two types of audiences—the “sit back and watch” people and those who want to interact online. Were the Hollywood people deluding themselves? No, they were just looking for something they might not recognize if they saw it.

“There’s a great opportunity to blend television and the online experience, but I don’t think anyone’s cracked the code on that yet,” says Rob Jennings of America Online to New Media. “The buzz in Hollywood is how to actually make that bridge.”

Madeline Kirbach of M3P, Microsoft Multimedia Productions, said, “We’ve probably seen a couple of thousand proposals, we’ve taken to development a couple of hundred, then to production a couple of dozen. That gives you an idea.”

For all the TV talk—even Microsoft was calling its programming “shows” and referring to “channels”—the Web is not television. Television, like print, is a one-way medium. That’s not value judgment; that’s fact. The telephone and the Internet are two-way media. That doesn’t make them better, only different. And different is what punches new ideas through.

In Fall 1997, AOL found the bridge Jennings was talking about and launched its AOL Network with “infotainment” shows, interactive sci-fi, comedy, and Hollywood themes.12 At that time, there was no streaming video, but the programming used TV-style titles (“The Hub,” “Kids Only,” and “Newsstand,” for example) and TV celebrity Joan Lunden hosting chat sessions and updated content sections on “AOL Today.”

By February 1998, AOL was averaging 600,000 users. A media tracking study released in May of that year by McCann-Erickson advertising agency called the AOL Network “the fastest growing network.” McCann charted AOL on a timeline that included ESPN, CNN, and MTV. The agency concluded: “Not only is AOL the fastest-growing network; but, at its current rate of growth, it will soon be the number-one cable network.”

AOL president (and former MTV executive) Bob Pittman told the online magazine Adtalk: “The TV experience is very different from the PC experience. We are confident that we will play a leadership role when the time is right.”

When’s the time right? The week before the McCann-Erickson study was released, AOL had agreed to acquire NetChannel, once a competitor to Microsoft’s WebTV, which enables TV users to view online content on their TV sets. NetChannel would allow AOL to expand beyond the users-only base to the 98 million TV households in the United States.

The ground for new channels was fertile as AOL made its move. Cable had whittled away at the shares of the traditional TV networks. The original Big Three had become the Big Four (by adding Fox), then the Big Six (with UPN and WB in the mix), with others testing the traditional TV network waters. When NBC-TV’s Seinfeld aired its last episode in the series, the network also promoted the last seasonal episode of ER on the same night. Focusing on the end of the TV seasons indicated that, at least at the network level, NBC was working on the old TV paradigm.

“Seasons” came from the days of TV as a truly mass, national, homogenizing medium. That was a time when all school systems worked on a September-to-May schedule, all moms stayed at home and baked bread and apple pies, and all families vacationed at the same time, reducing summer TV viewing.

This is no longer the case. The new paradigm is the viewer’s ability to watch anything at any time, whether it’s distributed by traditional mass media, individualized media like video rentals, or one-on-one online downloads.

Even though NBC-TV followed the old paradigm, as a company NBC was first among the conventional broadcast networks to embrace the idea of media convergence. As Wired put it, “NBC has staked its entire future on convergence—on the assumption that unlimited choices in entertainment, information, and transactions, in video, audio, and text, are moving inexorably onto a single home appliance, in a way that undermines traditional media economics.”

Wired pointed out that at the time NBC entered its agreements to mine cyberspace, the NBC-TV network was on track for a record $1 billion in annual profits while five other broadcast networks were at best barely breaking even. When he first joined the network, NBC president and CEO Robert Wright “would grimly tell advertisers, competitors, and underlings that the networks had to re-make themselves—or die,” reported Wired. Sure enough, NBC did so, making itself ready for new media.13

“New media” has so many meanings. It’s the CD-ROM dictionary that allows you to virtually examine the quality of aba or to speak Komi like a Zyrian14. It’s the digital downlink that helps you bypass cable or broadcast television. Most often, “new media” means the Internet generally and the World Wide Web specifically.

I concentrate on the Internet because of its rapid impact and its potential as an advertising medium. In The Internet Advertising Report,15 Morgan Stanley’s Mary Meeker suggests that “the Web may be the single most important development in technology since the debut of the PC, and that, in time, it should have a pervasive effect on our daily lives.” The Internet was growing at an unprecedented pace, “creating enormous opportunities for investment and wealth creation,” Meeker says.

Interviewed by Time Digital, she outlines six major issues facing the Internet:

1. Figuring out the appropriate company valuations. (In The Internet Advertising Report, she says that investors like subscription- and transaction-based companies more than advertising supported companies.)

2. Determining which companies provide the best portals to the Web. The contenders were Yahoo!, America Online, Netscape, Microsoft, Excite, and C/Net. “These companies are creating assets like those created by NBC, CBS, and ABC in the early days of TV broadcasting.”

3. The growth of Web commerce and advertising revenue. “We think Web retailing will grow dramatically and Web advertising will grow three-ish times the 1997 level.”

4. How quickly enterprises launch Web sites, create in-house online resources for their employees, and develop direct online links with other businesses.

5. How successful America Online will be with its transition to the Internet.

6. How Microsoft’s “relentless effort” to gain market share in all categories will impact other players.16

When my company applied for www.shanemedia.com back in 1994, we were one of 22,511 who requested a URL that year. That seemed like a lot at the time. But compare that figure to 1996, when a staggering 657,000 domain names were registered. When InterNIC began registering names, in 1985, there were only 29. Now the numbers are in the 6,000-plus range per day!

About 50% of U.S. companies had their own Web sites by the end of 1997. Of those, about 66% used them mostly for advertising, marketing, and public relations, according to RHI Consulting, which commissioned the study among 1,400 chief information officers. The best indication I had that the Web was to be ubiquitous was when Frank, the Exxon dealer across from our office, told me to log on to his site for coupons.

As part of a wide-ranging survey on a variety of media issues, the American Association of Advertising Agencies reported in 1998 that 55% of advertisers were buying interactive media to advertise their brands. (See Figure 9–5.) Jake Winebaum of Disney Online told Wired that eight car companies were advertising with Disney.com.17 “I’ve called on car companies for 12 years, selling print ads, television shows, and now sponsorships on the Internet. The difference in the meetings I’ve had vis-á-vis the Internet and all other media has been profound: In the Internet meetings, they’re saying, ‘Jake, we’re selling cars online—lots of them.’”

Benefits and Drawbacks of Online Advertising

Earlier we looked at the benefits of other electronic media: television’s visual appeal, the way it permeates American life, its mass appeal, its reach, and its variety. Cable has similarities with broadcast TV as well as its own unique attributes: vertical niches, geographic targeting, and upscale viewers. Radio offers flexibility, ubiquitous reach, cost-efficiency, and the “theater of the mind.” Advertising on the Internet has its own assets and liabilities. The main assets are:18

• Advertising is accessible, on demand, 24 hours a day.

• Distribution costs are low, so reaching a million targets is the same as reaching one.

• Content drives access, so opportunities for market segmentation are great.

• A one-on-one, direct marketing relationship can be created with the consumer.

• Content can be updated, supplemented, or changed at any time.

• Responses are highly measurable.

• Navigation is easy. The consumer controls the destination and spends as much time as desired.

The case against Internet advertising presents these objections:

• There’s no clear standard for measuring success.

• The variety of advertising formats on the Internet is so great that comparisons from ad to ad are difficult.

• Traditional advertising needs—ratings, share, reach, and frequency—are difficult to assess.

• The audience is still small.

• Online service providers store, or cache, Web pages to speed up delivery to subscribers. The original site’s server doesn’t record page views properly.

• Text-only browsing allows images to be turned off and advertising is not viewed.

• If the page is longer than the browser viewing space, advertiser content at the bottom of the page may not be seen.

• Users may leave a page before an ad downloads.

Like advertising in any traditional medium, Internet advertising is all about reaching potential customers and making an impression on them. Web publishers are responsible for attracting traffic, and advertisers are challenged to develop a creative experience to capitalize on that traffic.

“Well-designed advertising creative, delivered in the right environment with complementary content, is a key driver of advertising success,” says The Internet Advertising Report. “It is important that ads not be too intrusive, and we believe the more an advertisement seems like a value-added service to the user and less like an invasion of privacy, the more successful that ad will be in driving traffic or business to wherever it is connected.”

FIGURE 9-5 The Internet and the World Wide Web generate new ideas just by being there. The Property Channel, a Web site for the real estate industry, ran this ad for sellers in Advertising Age. Used with permission.

The Report suggests that a Web site should be an advertisement in itself and uses Absolut Vodka (www.absolutvodka.com) and Clinique (www.clinique.com) as examples. Those sites “have attempted to create compelling content and interesting and informative resources for users about their products, industry, or even content (through games, and so forth).”

Revenues for Internet advertising increased 200% per year between 1996 and 1997 with no expectations that the increases would level off. What brought in all that money? Here are some answers:19

• Links. Anything on a Web page that drives traffic to another site is a link, also known as a “hyperlink.” A link can be a button, hypertext, or a banner. To understand the importance of links, consider the fact that Yahoo!, Excite, Infoseek, and Lycos spent $5 million to be on Netscape’s search page. That positioning puts them in the way of an enormous amount of traffic that comes through the Netscape site.

• Banners. Typically, a banner is a horizontal rectangle that looks like a little billboard. (Some advertisers actually call them billboards.) Typical size is 468 × 60 pixels. The banner contains text, usually the advertiser’s slogan. GIF, Java, or other animation tends to increase response rates.

Many banners house an imbedded link to the sponsor’s site. That link creates a “click-through” and is called a “nonenhanced” banner. With an “enhanced” banner, the user never leaves the original page. All the advertising appears on the banner.

The most effective banners are targeted specifically to the user viewing the page, based on registration at the site, a previous link, the browser, affiliation (AOL, Prodigy), and domain (.edu, .com, .org, etc.).

• Click-throughs. Some banners are sold by impression, others by the number of times users click on the ad and link to the advertiser’s Web site. The advertiser gets a sense of the results of the campaign rather than estimates that resemble radio or TV ratings.

Not surprising, one of the basic rules of selling and copywriting works in the multimedia environment: banners with the words “Click Here” increase click-through rates from 40% to 300%. It pays to ask for the order!

• Buttons. Like banners, buttons offer a click-through, but usually to a software download site. Buttons are typically 120 × 90 pixels or 120 × 60 pixels. Some buttons allow users to download software directly, while others link to a product page with descriptive text.

• Key words. When a search engine looks for a topic, it does so by key word. Advertisers to buy key words that relate to products or services. The advertiser’s banner is shown when the user searches for the advertiser’s word.

• Portals. Yahoo!’s Tim Koogle calls portals “the only place where someone has to come to connect to anything or anybody in the world.” Yahoo! is a portal, so Koogle spoke in hyperbolic terms. An advertising portal is a linkable graphic in the tool bar area of a site that links to another site specified by the advertisers.

• Interstitials. The most old-media-like of new media advertising, interstitials are flashes of imagery or branding information that appear between pages of a site. They’re comparable to single frames of a TV commercial.

The online magazine Media Central Digest predicts, “As sites become increasingly application-like, for example Blender com and BeZerk’s NetShows, interstitial advertising will contribute to the goal of making the Web more like television by interrupting the content with an ad.” (There was no indication of whose “goal” that might have been.)

• Pop-up windows. Separate windows that appear over site content while a page is loading are called pop-up windows and are approximately 245 × 245 pixels (that’s my imprecise count). The idea is to increase impact without slowing down the user’s Web experience.

CondeNet Marketing created the five-second pop-up window for its food and travel sites in 1997, and they were embraced by the industry because they increased click-throughs by 200%.

• Offline ads. These are coupled with “push” content, where the user requests tailored news or information. As an example, if a customer subscribes to PointCast in order to get CNN news, PointCast automatically begins running when the customer’s computer is not in use, replacing the Screensaver with CNN headlines. (The viewer selects up to ten channels of content.)

Animated ads are delivered to each content screen with links to the advertisers’ Web sites. The service allows advertisers to customize delivery based on content requested, demographics, or psychographics.

• Inline ads. This type of ad is an online “advertorial” positioned within a site, thereby adding credibility to an advertising message. Auto manufacturers have used this idea to great advantage to create online “showrooms” for vehicles.

• Sponsored content. Another variation on old media, sponsored content refers to an advertiser’s “ownership” of a site the same way a TV advertiser “owns” a show or a sporting event by purchasing sponsorship rights.

What works? The Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB) reported that banners were responsible for 96% ad awareness. The same study showed real weakness for click-throughs in the same awareness category.20 In contrast, Berkeley Systems, the operators of the BeZerk games site www.bezerk.com, claimed that interstitials generate even higher brand awareness than banners.

Whom do we believe? Since Berkeley is home of “You Don’t Know Jack” and other interactive games, their findings about interstitials are true more for their site than for others.

A Grey Advertising study cosponsored by SOFTBANK Interactive and the Advertising Research Foundation found that the size of an ad is important when the advertiser wants to be noticed (why advertise otherwise?). Large-format ads produced higher recall than banners. Over three-quarters of respondents (76%) remembered seeing interstitials; 71% recalled split-screen ads. In contrast, 51 % recalled banner ads.

In questions about whether the ads were irritating, 15% said interstitials were; 11% said split-screens were; and 9% said banner ads were. Respondents favored enhanced banners, which do not take them off the site they had chosen to visit.

The 1998 Advertising Age Interactive Media Study indicated a decrease in response to online advertising compared to 1997 figures. The survey asked, “How often do you look at banner ads?” In 1998, 48.5% said “never,” up from 38.7% in 1997. On the other hand, more than a quarter (26.5%) of online users said they’d be more likely to click on video ads, and 24.5% said they would download special software to view video ads. The drop in interest in banner ads could be a product of online users becoming bored with banners and looking for something new.

All indications are that response to banners drops dramatically after the first or second viewing, so the best response rates come from banners bought for reach, not frequency. Thunder Lizard Productions, presenters of Web advertising conferences, advised, “Buy small (for larger sites, less than 10% of inventory) and buy wide (lots of sites).”

HotWired Network translated “buy small and buy wide” into a service called “reach-frequency management.” Their system allowed targeted visitors to see an ad for only a specified number of times before the ad rotated on to different visitors. In this way, an advertiser could show an ad to 50,000 unique Web visitors no more than four times, thus creating 200,000 impressions.

Doubleclick introduced a similar frequency management feature when they launched their service in March 1996. Doubleclick claimed that few Net surfers will click on an ad banner after seeing it more than four times (less than 1 %, they said). By comparison, nearly 3% click on first impression.

Internet Profiles Corp., the company that provides I/PRO Web audits, also introduced an automated buying service, called “Dispatch.” The goal was to help media buyers compare advertising buys across a variety of sites. Until I/PRO’s announcement, there had been no standard way to submit online campaign data to Web sites and track ad performance across all the sites in a buy.

While selling banners and other online advertising, GeoCities developed what they called “neighborhoods” for their million plus “homesteaders,” the name GeoCities gives their online visitors. The concept combined GeoCities advertisers into 40 special interest areas, like “Napa Valley,” which covered food, wine, dining out, and “the gourmet lifestyle,” as they termed it. For the Visa credit card company, GeoCities added a section to Napa Valley called “Restaurant Row,” where users could read recipes and restaurant reviews and post their own if they wanted. The site also offered to build free Web sites for epicureans.

FIGURE 9-6 Note the need for experience in national media sales or an ad agency. When this ad ran in late 1997, few people had experience in new media selling. Courtesy mplayer.com. Used with permission.

GeoCities, HotWired Network, and Doubleclick are distant cousins of traditional networks like ABC, CBS, and NBC, linking advertisers rather than local media outlets. Each operation provides one-stop shopping for an advertiser trying to reach large numbers of Web users one at a time.

LinkExchange, on the other hand, is an all-new model based on the specific needs of the Web. It is a banner-swapping network of more than 100,000 sites that deliver about four million ad views per day, according to statistics from I/PRO. Telling the LinkExchange story, Wired calls it “a good old-fashioned Web success story—youth, idealism, a good idea, 24-hour workdays, and, somewhere down the road, the possibility of making lots and lots of money.” Two Harvard computer science graduates, Sanjay Madan and Tony Hsieh, started LinkExchange as a side business during their first post-collegiate jobs at Oracle.21

The idea behind LinkExchange is to help small business clients generate traffic by linking sites. “We want to bring banner advertising to everyone on the Web, not just the big corporations,” says Madan. From that goal was born the world’s largest ad network, identifying 1,600 narrowly defined interest groups so advertisers can target precisely.

Because LinkExchange is supported by sponsors, members of the network advertise their sites for free. Members determine where they want their banners shown and what type of targeting will work best—by category, by rating level, and by business status. Here’s how LinkExchange describes the process in their online media kit:

Our rating system and filtering technology helps ensure that the banners appearing on your site are appropriate for your audience, and that your banners appear on sites that would appeal to your potential visitors.

Please Note: LinkExchange does not accept sites containing adult material, links to adult material, or other inappropriate content as outlined in our Terms and Conditions.

You can view your stats in a summary or daily format. Wr e provide you with up-to-the-minute statistics about:

• The number of times your site is visited

• The number of times your banner is displayed

• The number of times your banner is clicked on

• Your display-to-click ratio

LinkExchange also maintains a searchable directory of all of its members, with each site’s target categories. Precision targeting is the most powerful aspect of the Internet as an advertising medium. The advertiser has the ability to filter messages to selected audiences based on exacting criteria and thus dictate the composition of an advertisement’s audience.

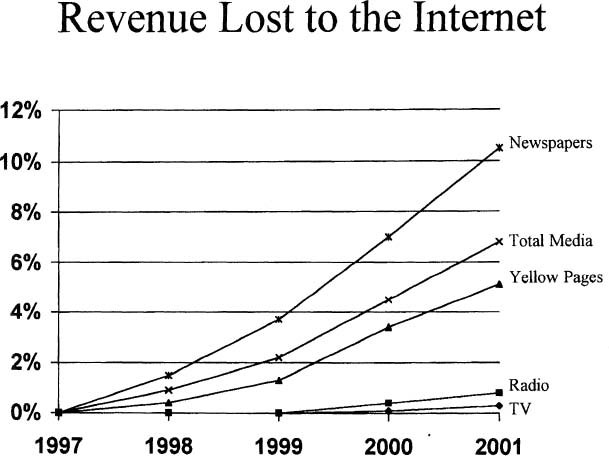

Projections developed by Forrester Research and quoted in The Internet Advertising Report show newspapers to be the long-term victims of Web advertising. More than 10% of newspaper revenues will be funneled to online advertising by 2001, compared to 5.1 % from Yellow Pages, 0.8% from radio, and 0.3%) from television. (See Figure 9–7.)

Advertisers have to approach the Web the way they would approach any form of traditional media, by asking, “What’s the best way to reach the prospects for my goods or services?” Morgan Stanley’s The Internet Advertising Report outlines it this way:

When advertisers make media buying decisions, they use a rate card supplied by each of the potential sites, magazines, and the like. The rate card lists the rate (most likely in CPMs) that the publisher charges for each type of advertising product it offers…. Web sites might list the CPM for their banners, along with prices for products like buttons or key words, all tailored to the particular vehicle that site might provide.

In a discussion of Web pricing, Thunder Lizard, the conference production company, relied on old-fashioned imagery: “Ad rates on the Web are like laws in the wild west—they’re tough to enforce, every town is different, and it helps if you’re carrying a big gun. The most common model charges between 20 and 50 dollars per thousand impressions, but variables include type of buy, targeting, duration, and number of impressions per month.”

An unnamed Tribune Ventures executive mused to MediaCentral Digest, “When your ad rates are $50 per thousand and you only have 10% to 50% sell-through, do you take a lower price? Or do you drop your CPM? No one has the right answer yet.”

At Web Advertising ‘98, a conference sponsored by Advertising Age, the response was, essentially, take the lower price: “It’s a buyer’s market at this point—more than 50%) of inventory goes unsold—so the bargains are definitely out there.”

FIGURE 9-7 Traditional media stand to lose 6.8% of revenues to Internet advertising by 2001, if projections by Forrester Research, quoted in The Internet Advertising Report, are accurate. Newspapers stand to be the biggest losers.

The Cost-per-Thousand (CPM) Myth

CPMs vary widely on the Web, much to the consternation of advertisers used to traditional media. To the national or network television buyer, eyeballs are eyeballs; the more eyeballs, the more efficient the buy. They look at Internet advertising as costly, as much as 66% higher than television. That’s true. Television is, after all, a mass-reach medium.

The Internet advertiser must remember first that while the Net reaches large audiences in terms of numbers, each audience member is reachable in a one-on-one setting. LinkExchange identified 1,600 audience categories, and that’s just a start! There are potentially as many categories as there are users.

This takes the discussion about CPM in Chapter 8 on selling radio and magnifies the absurdity. New media are about true “declassification” (to borrow Alvin Toffler’s word) and “1:1” communication (using Don Peppers’ ratio).

“Most of what is published by the analyst community promulgates the Web CPM myth,” wrote Rick Boyce in a special report for advertisers published by the IAB. “As any media planner will tell you, it is impossible to compare CPM objectively across different media without accounting for the level of targeting the advertiser wants to reach.”

Boyce illustrated his idea with this example:

A 30-second network prime time spot delivered a $12 CPM against all U.S. households.

Refine that audience to adults 18–49 with a household income of $50,000 a year and the head of household with a year or more of college, and the CPM jumps to $49.15.

“As a single point of reference,” Boyce said, “consider that a banner schedule can be purchased on Quote.com—which delivers an audience with an average household income of $110K and 70% college graduates—for under a $50 CPM. Once television CPMs are adjusted to account for reaching a specific target audience, the economies of Web advertising—particularly for reaching discreet [sic], affluent target audiences—becomes clear.”

Pricing strategy for most sites is based on a variety of factors: market conditions, research information, feedback from the sales force, and availability of advertising opportunities on a particular site. C/NET, for example, operated nine sites in 1997 with price ranges from $15 CPM to $100 CPM. The company’s shareware download service increased pricing from $20 CPM to $30 CPM that year based on supply and demand.

Run-of-site advertising on C/NET’s search engine was decreased that same year from $20 CPM to $15 CPM to stimulate demand, according to MediaCentral’s Online Tactics.

Mecklermedia vice president and general manager Chris Elwell told the same publication: “Content sites are not like search engines. There’s a cost associated with creating content, and therefore, ad rates have to reflect continuing costs of content creation.”

Elwell suggested that the CPM for an online magazine for consumers might be $35, while a trade publication can justify $100. “If you can prove to the advertisers that you have a good audience, you should have to charge more,” he said.

NOTICEABLE ADVERTISING

In a 1997 study for the IAB, MBinteractive concluded that “online advertising is more likely to be noticed than television advertising.”

First, Web users are actively using the medium instead of passively receiving it.

Second, there’s less advertising online. The typical ad banner is 468 × 60 pixels, a total of 28,080 square pixels. A typical default screen is 640 × 480 pixels, or 307,200 square pixels.

That’s 91.4% content against 8.6% advertising, something no other electronic medium can claim!

The battle for local community information on the Internet has been heating up since America Online created Digital City with localized information for cities across the United States. Other entries in the local market were Microsoft with Sidewalk.com, CitySearch, CityWeb, and NBC’s Interactive Neighborhood, created for NBC-TV affiliated stations.

Cox Interactive Media was actually one of the first, but received little national notice because they approached the idea conservatively, establishing Access Atlanta and refining the site accessatlanta.com before launching other city services. Cox took pains to go deeper than the typical information. Any site can report a weather emergency, but Cox sites add road conditions and life-saving information. As the newsletter iRADIO pointed out, the Cox sites are more than simply “community bulletin boards.”

Cox owns plenty of media outlets, but, as Cox Interactive’s Michael Parker put it, “We’re not putting our newspaper, radio, and television stations online, that is the formula for sporadic visits.” Instead, Parker told Advertising Age, Cox wants to communicate that their local sites “provide information [and] emotional attachment.”

Cox sites do use their media outlets well. Access Atlanta, for example, gets weather information and lottery numbers from WSB-TV. There’s access to editorials from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper. “Do research in the Journal-Constitution’s archives,” says a link. Traffic information comes from WSB Radio. But the site is self-contained.

Tribune Ventures, the interactive arm of Chicago’s Tribune Company, maintains Web presence for its newspapers in Chicago, Orlando, Fort Lauderdale, and Newport News, Virginia. The company also owns 20% of Digital City, which has sites in each area where Tribune owns papers. (The other 80 % of Digital City is owned by AOL, and the service began in 14 cities.)

I received an advertisement from a promotion company in Pennsylvania with copy that sums up the new media paradigm: “This is America. You’re allowed to shop for 200 pens at 1 a.m. if you want to.”

This is the point where all of life merges and converges with media—online commerce. People want to check their account balances, transfer funds, and book flights when they want to. Time zones are irrelevant. The nine-to-five office is irrelevant.

IBM’s advertising for its e-business (electronic-business) systems seemed hyperbolic at first: “E-business will transform the economy, alter the rules of competition, and shake up the status quo.”22

Hyperbole faded as predictions were made of $176 billion worth of goods expected to be purchased online in 2001. Those numbers were revised upward by Forrester Research in 1998 when they projected business-to-business electronic commerce at $183 billion in 2001 and online retail revenues at $17 billion. The predictions came after 1996 figures reached $1.3 billion and the Department of Commerce projections of $300 billion.

Fueling the unprecedented totals were online trading of stocks and mutual funds by Charles Schwab, which opened over one million new accounts online. Cisco Connection Online, a business-to-business site, reported selling $11 million in networking equipment per day! Dell Computers claimed $5 million a day from its Web site. Microsoft’s Expedia travel service sells airline tickets at the rate of $4 million a week from its site. Ticketmaster sold $35 million in concert and event tickets from its Web site in 1997, approximately 3%) of its total ticket sales.23

Electronic banking was available to 60% of households in North America through a network of 16 banks and VISA USA. The collaboration established a standard for Internet bank card security, overcoming a deterrent to e-commerce: consumer fear of credit information being stolen online.

The most prominent story in e-commerce was Amazon.com, Inc., billed as “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore.” Founded in 1995, Amazon quickly became the leading online seller of books. (While the company sold compact discs, videotapes, and audiotapes, books comprised more than 90% of sales in 1997.) All Amazon purchases are made on the Web at www.amazon.com and are delivered via third party services such as UPS and FedEx.24

At retail, the total book market is about $26 billion in the United States and $82 billion worldwide. By comparison, Amazon online sales are insignificant: a cumulative total of $98 million through the third quarter of 1997, to approximately 610,000 customers.

The difference between Amazon and a retail bookseller is space. The size of the retail store limits its inventory, which is why many booksellers create niches based on the population available to them (i.e., the University bookstore) or categories of books (business books, mystery books, etc.). As a Web-based business, Amazon has no such limitations, and offers most of the 1.5 million English-language books believed to be in print, with a total of 2.5 million titles. Amazon’s success attracted national bookstore chains Barnes & Noble and Borders Group to enter online retailing.

A report on Amazon’s performance by Everen Securities gave a glimpse into the future of online selling: “On the basis of our analysis of retailing costs, we believe the efficiency of the Web site as a retailing mechanism should lead to significant cost advantages over even the most efficient of location-based retailers.”

The investment community responded also to K-Tel International, the direct marketer of music CDs and tapes, when it said it would launch online sales; to CDNow, when the online music seller went public; and to N2K when it sold stock shares to an underwriting group.25 Music sellers are expected to gain even further ground in e-commerce once encryption technology allows downloading music to consumers without fear of copyright violation.

When you’re selling online advertising, you’re probably going to be regarded as the expert. Users of traditional media will ask for help in presenting their messages online. On the other hand, new media is a field full of experts—the users themselves—some of whom have had a mouse in their hands since infancy.

The basic rules for creating an Internet marketing plan and implementing it with creative messaging follow:26

View the Internet as an Adjunct

“Online and offline media are a perfect couple,” says Kim Bayne in The Internet Marketing Plan. Building Web presence is not enough. Advertisers need to be reminded to use traditional media to drive traffic to a Web site.

“If your direct mail campaign is working, don’t trade it for the Internet,” Bayne advises. “If your TV campaign is working, don’t trade it for the Internet. Use the Internet to enhance programs that are already working. If you notice a shift in how customers are gathering your literature and how they are contacting you, then it’s time to regroup—but not before.”

The “eyeballs are eyeballs” theory of media biding does not apply to the Internet. Evan Schwartz, author of Webonomics, suggests creating a “sense of community among a group of ultradesirable clients.”

Give the customer advantages that are as good as what you’d like to get from the customer. If you’re asking for personal demographic information, make it worth the customer’s while by offering incentives such as gifts, advice, discounts, or entertainment information. For example, Chrysler offered its vehicle owners free wiper blades for participating in an online survey, according to Schwartz. Others offer online users credits against airline frequent flyer miles, stays at hotels, and other noncash incentives.

Advertisers can communicate with one, two, three, or thousands of customers at once. E-mail can provide customer service, build relationships, distribute newsletters, and so forth. “If you choose to contact your customers via e-mail,” Bayne warns, “do so with caution, incorporating business ethics and professional courtesy. If someone has contacted you, you know they are already interested in your company. This is the time to ask them if they would like to receive regular news through either e-mail or another method.”

Why do customers come back to a Web site? Because they perceive that the site offers continuing benefits. New and updated information is a key benefit online. Bayne suggests adding to every update a note of the date and the person who updated the files.

In Selling on the Net, Herschell Gordon Lewis tells us to highlight whatever’s new. “It can be new product or new uses for product. Healthy Choice offers a new healthy recipe, using their products of course, every day.”

Schwartz reminds us that “there’s no such thing as a completed Web site. Even at the best-designed Web location, information is as perishable as a baker’s goods. Today’s aromatic loaves are tomorrow’s day-old bread. Don’t let your site get stale.”

“Don’t sign up for an Internet account intending to try it for a while,” Bayne advises. “Take your Internet opportunity seriously. Creating and maintaining an Internet presence takes dedication, time, ingenuity, time, resources, and time.”

Ads in cyberspace are not print ads, and they’re not television ads. They’re interactive online ads. Advise advertisers to investigate the unique features of the Internet and to take advantage of them.

Lewis advises Net copywriters to “never be the bottleneck. Use a computer powerful enough to handle your site’s load with adequate speed connecting to the Internet so the bits aren’t waiting in line on your end.”

He also suggests using “grabbers” early in your text. Since text loads before graphics, the text should make the visitor want to wait for the graphics. He says the word “free” still works in spite of overuse and abuse.

One more rule from Lewis: Offer interactivity early in the text. “Give them something to do.”

Early in the book, I tied advertising to the economy of abundance, saying advertising is impossible to separate from the economy as a whole. When supply outstrips demand (as in the U.S. economic system, for example), advertising fulfills an essential function: moving merchandise from the manufacturer to the consumer.

Where does supply outstrip demand even more than in the general economy of abundance? It happens in nations like ours that find an increasing number of workers working not in production or transportation of goods but in managing information. It’s been called “the information glut” and “the information explosion.” It’s even called “the information economy,” but that’s a misnomer if you define economics as the study of how a society uses scarce resources. In our lives, there’s certainly no scarcity of information!

In cyberspace, information is not only abundant, it’s overflowing. In traditional media there’s just as much. You may call it “data” rather than “information,” but it overflows regardless of its name.

What is scarce is enough attention to attend to all the information that tempts us. “Attention has its own behavior, its own dynamics, its own consequences,” says writer Michael Goldhaber of the University of California at Berkeley.27

Because attention is a limited resource, Goldhaber’s theory is that ours is—or will be—an “attention economy.” Attention is scarce, Goldhaber wrote in Wired, “and the total amount per capita is strictly limited. … The size of the attention pie can grow as more and more people join the world audience, but the size of the average slice can’t.”

The Internet creates an unusual context for the attention economy. Goldhaber writes:

In cyberspace, there is nothing natural about large-scale divisions like cities, nations, bureaucracies, and corporations. The only divisions, and rough ones at that, are among audiences, entourages, and what could be called attention communities. Each community is centered on some topic and usually includes a number of stars, along with their fans. Attention flows from community to community. Below this primary exchange will flow the less important exchange of goods and materials.

He says the attention economy changes advertising, too, since “ads will exist only to attract and direct attention.”

That information provides a good background for understanding the function of advertising on the Internet.

Review Highlights and Discussion Points

1. Nobody knows what to call new media. Lots of people have tried to come up with just the right words. “Merging and converging” were the favorite words during the waning years of the 1990s when things were, indeed, merging and converging. Add to this the word “emerging.”

2. A good example of morphed media is MSNBC, the marriage of “old” NBC and “new” Microsoft Network (MSN). “Converging” fits MSNBC perfectly, given the combination of NBC-TV, that network’s affiliated stations, CNBC Cable, and msnbc.com online.

3. New media are generally accepted quickly by “early adopters” who want to be the first with the latest. Then the new media spread slowly through the population.

4. “Slowly” is not a word that fits with merging, converging, and emerging new media. Internet technology expanded so quickly that people began talking about “Web years” the same way they would about “dog years.”

5. The explosive growth of the Internet since 1995 belies its beginnings in 1969 when the Pentagon established it to link government and university computers. At first, the Internet simply reserved phone lines for joint research projects.

6. Paralleling the Internet’s quiet academic beginnings was the growth of interactive multimedia. It began with the Pong video arcade game, introduced in 1972—which was the Stone Age in digital terms.

7. Plain old news and information were the leading reasons consumers went online. In 1998, the numbers of Net users seeking information was up, not down.

8. Newspapers were an early staple on the World Wide Web, probably to attract some of the cachet of electronic media for the oldest commercial medium.

9. In a promotion for its annual convention and technical exhibition, the National Association of Broadcasters in 1998 suggested that we were “living in the interactive interim.”

10. Research by Arbitron revealed that more than one-third of television households in the United States had an interest in using their TV sets for some PC functions.

11. The U.S. Department of Commerce reported, in April 1998, that online traffic was doubling every 100 days and that electronic commerce would likely reach $300 billion by 2002.

12. There was a debate in the late 1990s about whether the World Wide Web was cutting into TV viewing levels. BJK&E Media Group indicated that early adopters of the Internet gave up their TV habits in favor of online activity.

13. The dilemma for online content producers was how to provide programming that satisfies two types of audiences—the “sit back and watch” people and those who wanted to interact online.

14. In the fall 1997, AOL found the link between “sit back” and “interact” and launched its AOL Network with “infotainment” shows, interactive sci-fi, comedy, and Hollywood themes. By February 1998, AOL was averaging 600,000 users.

15. “New media” has so many meanings. It is the CD-ROM dictionary. It is the digital downlink that helps you bypass cable or broadcast television. Most often, “new media” means the Internet, generally, and the World Wide Web, specifically.

16. About 50% of U.S. companies had their own Web sites by the end of 1997.

17. Revenues for Internet advertising increased 200% per year between 1996 and 1997, with no expectations that the increase would level off anytime soon.

18. The Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB) reported that banners were responsible for 96% ad awareness. The same study showed real weakness for click-throughs in the same awareness category.

19. Large-format ads produced higher recall than banners. Over three-quarters of respondents (76%) remembered seeing interstitials; 71% recalled seeing split-screen ads. In contrast, 51% recalled banner ads.

20. GeoCities, HotWired Network, and DoubleClick are distant cousins of traditional networks, like ABC, CBS, and NBC. They link advertisers together rather than local media outlets.

21. Projections developed by Forrester Research and quoted in The Internet Advertising Report show newspapers to be the long-term victims of Web advertising.

22. CPMs vary widely on the Web, much to the consternation of advertisers used to traditional media. The Internet advertiser must remember first that while the Net reaches a large audience in terms of numbers, each audience member is reachable in a one-on-one setting.

23. Pricing strategy for most Web sites is based on a variety of factors: market conditions, research information, feedback from the sales force, and availability of advertising opportunities on a particular site.

24. In a 1997 study for the IAB, MBinter-active concluded that “online advertising is more likely to be noticed than television advertising.”

25. The battle for local community information on the Internet has been heating up since America Online created Digital City with localized information for cities across the United States.

26. Hyperbole faded as predictions were made of up to $300 billion worth of goods expected to be purchased online in 2001.

27. When you are selling online advertising, you are likely to be perceived as the expert. Users of traditional media will ask for help in presenting their messages online.

28. Ads in cyberspace are not print ads, and they are not television ads. They are interactive online ads. Sellers should advise advertisers to investigate the unique features of the Internet and to take advantage of them.

29. Like advertising in any traditional medium, Internet advertising is all about reaching potential customers and making an impression.

30. When supply outstrips demand (as in the U.S. economic system, for example), advertising fulfills an essential function: moving merchandise from the manufacturer to consumer.

31. There is no scarcity of information, but there is scarcity of attention. The result is that advertising will be used to attract and direct attention.

1 The title of this chapter is borrowed from “Living in the Interactive Interim,” by Robert L. Lindstrom in the NAB’s magazine, On the Verge, March 1998, a promotion for the 1998 NAB Convention.

2 There was a new media timeline in “When Did You Get Multimedia?” in New Media, January 2, 1996.

3 The Market Facts studies were reported in Advertising Age in “Online Users Go for Facts over Fun” by Adrienne W. Fawcett, October 14, 1996. The following year it was “Information Still Killer App on the Internet” by Kate Maddox, October 6, 1997. The latest data I had before publication deadline was from “Survey Shows Increase in Online Usage, Shopping” by Kate Maddox, October 26, 1998. Check Advertising Age each year in October for the latest results.

4 “The New York Times on the Web,” Direct Marketing, August 1997.

5 A photograph of what looked like a little girl with her prize duck at a pet show or FFA awards program illustrated the “What’s the difference?” headline in an ad for IBM in Wired, December 1997.

6 The Kiplinger Washington Letter, February 17, 1995.

7 The Arbitron research was in “Living in the Interactive Interim,” cited above.

8 The U.S. Department of Commerce report in USA Today was cited in Chapter 1.

9 In my opinion, Nicholas Negroponte knows everything. Fortunately, he writes about some of it. See “The Third Shall Be First: The Net Leverages Latecomers in the Developing World,” Wired, January 1998.

10 The Nielsen review of Internet households was cited in Chapter 1. An Arbitron study showed that radio usage was also reduced by online activity an average of two hours per week.

11 The idea of an online Lucy Ricardo is from New Media, August 4, 1994. The article was “The Web’s Fall Season” by Paul Karon. That’s also the source of Hollywood’s quest for the bridge between “sit back and watch” and interactivity.

12 AOL’s new lineup was described in Broadcasting & Cable, October 13, 1997.

13 Randall Rothenberg interviewed NBC’s Robert Wright for “Go Ahead, Kill Your Television. NBC Is Ready,” in Wired, December 1998.

14 “The quality of aba” and speaking “Komi like a Zyrian” are for people who like to play with words.

15 The Internet Advertising Report was cited in Chapter 1.

16 “Morgan’s Mary Meeker: Look for the Net’s ‘Top Dogs’” by Maryanne Murray Buechner appeared in Time Digital, a supplement to Time, March 23, 1998.

17 Disney Online’s Jake Winebaum was interviewed in Wired, June 1998. The article was called, “The New Mouseketeer,” and it appeared just before Disney agreed to buy Infoseek and merge Disney Online with Starwave. The result of the Disney moves was an all-new Web presence called go.com.

18 I was surprised to find few examples of either benefits or liabilities of advertising online, so I assembled some for you from a variety of sources, most of them mentioned in the text. The Internet Advertising Report, cited previously, was the starting point.

19 The discussion of links, banners, and other online advertising opportunities also had to be collected from a number of sources: The Internet Advertising Report; advertising for GeoCities and www.geocities.com online; presentation materials for “CNN on Pointcast”; LinkExchange www.linkexchange.com; MediaCentral’s “Online Tactics”; and Online Media. Strategies for Advertisers, published by the Internet Advertising Bureau in Spring 1998.

20 The IAB study was reported in Advertising Age, September 28, 1997, and in MediaCentral’s “Direct Newsline,” September 25, 1997.

21 Sanjay Madan and Tony Hsieh of LinkExchange were featured in “Barter for Banners,” Wired, October 1997. I added promotional information from LinkExchange.

22 The IBM ads ran in The Wall Street Journal, December 8, 1997.

23 The remarkable online sales totals are from “E-commerce Becoming Reality” by Kate Maddox in a special report on interactive media and marketing in Advertising Age, October 26, 1998.

24 Amazon’s story is from Everen Securities’ Investor News, January–February 1998.

25 K-Tel, CDNow, and N2K were the subjects of “Internet, Music CDs Hit Right Key” by David Lieberman in USA Today, April 16, 1998.

26 For the “users guide,” I combined Kim M. Bayne’s ideas from The Internet Marketing Plan. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997, and Herschell Gordon Lewis’ columns in Direct Marketing, October, November, and December 1996, and January and February 1997. Lewis’ book is listed under Additional Reading.

27 The attention economy is real. Michael Goldhaber’s “Attention Shoppers!” appeared in Wired, December 1997, and was a prelude to a book he was working on. I can’t wait to read it.

Here are a few Web sites that relate to this chapter and additional reading not included in the Chapter Notes.

www.100hot.com—Tracks 100 top Web sites and groups high-usage sites by category, e.g., autos, books, etc.

www.cimedia.com—Cox Interactive Media and links to their city sites

www.clickz.com—Newsletters covering interactive agencies

www.cnet.com—Updates on interactive news from C/NET

www.electricvillage.com—Syndicators of Web sites

www.focalink.com—An online rep

www.forrester.com—Forrester Research is quoted often in Internet and new media stories. Forrester provides research data to subscribers. This site offers limited detail, but is helpful.

www.gossipcentral.com—Media updates and links to a variety of news sources. A source for “The Buzz” online newsletters (also at www.adtalk.com)

www.home.net—The @Home Network from Cox Interactive

www.iconocast.com—Internet marketing, market research, and e-commerce

www.mediametrix.com—Statistics on Internet usage

www.netlingo.com—An Internet language dictionary with a guide to online culture and technology

newmarket.net—They are Web developers and marketers. Their CEO, Tom Lix, coined the phrase “audience attention deficit disorder” to describe the effects of fragmentation on user loyalty.

www.sidewalk.com—City sites from Microsoft Network

www.zdnet.com—Ziff Davis publications site that is parent to cable channel ZDTV

Lewis, Herschell Gordon, and Robert D. Lewis. Selling on the Net: The Complete Guide. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books, 1996.

McKenna, Regis. Real Time. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

Miles, Peggy, and Dean Sakai. Internet Age Broadcaster: Broadcasting, Marketing, and Business Models on the Net. Washington, DC: National Association of Broadcasters, 1998.

Maddox, Kate, and Dana Blankenhorn. Web Commerce: Building a Digital Business. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Negroponte, Nicholas. Being Digital. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

Peppers, Don, and Martha Rogers. The One to One Future. New York: Doubleday Currency, 1993.

Tapscott, Don. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.