In the fall of 1962, there was a big parade in Griffin, Georgia, then a town of about 15,000 people located about 40 miles south of Atlanta. I don’t remember the occasion, but there must have been a football game that weekend. High school bands, clowns, and city dignitaries filed from Highway 75 around the town’s main street, where the pool hall, the variety store, and the radio station were located.

It’s the radio station that counts in this story. WRIX wanted to serve the citizens of Griffin who couldn’t make it to the big parade, so we snaked a long mike cable to the front of the building, giving us a second-floor vantage point. The station’s sales manager sat in the window, watched the activity, and described the scene to the listening audience.

At the back of the building, with a view of only the alley between our building and the town’s movie theater, I ran the control board, inserted the commercials (for the variety store), and experienced the parade—by radio.

My wife, Pam, had a similar experience at baseball’s spring training in 1998. I was working with the Astros radio network as a talent coach for members of the broadcast team. Pam joined us for a few innings in the broadcast booth. She quickly discovered that, unless you’re calling the play-byplay and seated right at the window of the booth, you can’t see the field or the players from the booth. She had to rely on the commentary by Astros announcers Bill Brown and Alan Ashby.

“Sorry you can’t see more,” said Bill. “That’s OK,” Pam replied. “This is the way I hear the games on the radio. I’m able to tell what’s going on.”

That fall day in Griffin when I was 16 and the spring day 30-something years later are terrific examples of radio at its best: descriptive commentary that’s a real service to listeners stuck in back rooms, unable to watch the clowns or the cheerleaders or the home run.

Call it “theater of the mind;” it’s radio’s sion and cable services show the pictures, unique contribution to mass media. Televi- while various forms of interactive media mix and match sounds, pictures, text, and animation. But only radio leaves it to the listener to create the image conjured by the words.

Before television, the “pictures” that entertained America were on the radio. A man named Raymond opened a squeaking door on the drama Inner Sanctum, and the stories told behind the door made spines tingle for a half hour. The main character of The Shadow was a mental projection against a foggy night full of smoke from coal-burning furnaces. Those pictures were drawn with words and sound effects in the radio of the 1930s to the 1950s.1

“Radio is pure sound,” says Jack Trout, the man who gave the marketing world the positioning concept. “To do good radio you have to understand how to use sound and sound effects. Unfortunately, most creative types are picture-oriented, not sound-oriented.”2

“Radio is an ideal sales vehicle to stretch the imagination as well as the mind,” says Bill Burton, president of the Detroit Radio Advertising Group. He continues:

What better medium to sell the great aromas of perfume, shaving lotion, a warm vegetable soup for lunch or the smell of turkey and ham cooking? There’s no way you could convert these wonderful aromas to picture or film—but the visualization in the mind can be overwhelming. All great radio takes place in your mind. The characters and situations you identify with, the taste, smells, emotion, all come to life through the power of your imagination.

Advertising legend David Ogilvy called radio “the Cinderella of advertising media,” because it often was left behind by major agencies.3 In 1983, when he published Ogilvy on Advertising, radio represented only 6% of total advertising in the United States. Radio’s share of the advertising pie has grown only slightly since Ogilvy’s remark, capturing 7.1 % of advertising dollars in 1997.

“Have the big agencies discovered that radio is a lousy way to advertise?” asked John Emmerling of New York’s John Emmerling, Inc., in Advertising Age. Emmerling answered his own question: No. “[T]he large shops are scared stiff of radio.” He explained:

Consider the account executive who has the temerity to suggest a radio campaign and must face the wrath of the creative director (probably reached at poolside in Beverly Hills where he is attending yet another TV shoot).

“Radio?” the CD sputters, “my top people are all too busy creating world-famous TV spots.” After this initial outburst he might deign to assign a junior producer to adapt the national TV jingle to a 60-second length. “If you need some announcer copy,” he allows, “one of the copy typists can whip something out.”

The rewards of selling radio in the age of television’s 10-, 15-, and 30-second “spotlets” (Emmerling’s word) include the fact that radio still offers “an affordable 60 seconds. And in that long, luxurious time span,” he wrote, “you can involve a listener. For when consumers perk up and actively imagine the radio spot’s situation, an enduring ‘mind picture’ is created—and your product’s name and position can be indelibly stamped on a receptive mind.”

Emmerling also cited radio’s audience segmentation, low production costs, and speed of production as key benefits to the medium. “They add up to flexibility that lets you take quick advantage of momentary changes in a marketing situation.”4 (See Figure 8–1.)

The Benefits of Radio as an Advertising Medium

Radio’s two major selling points are:

• Flexibility. If an advertiser has a change of price, a new location, or a special shipment, radio is ready to create an announcement at a moment’s notice to help the advertiser who missed the newspaper’s deadline or who cannot afford to produce new video for commercials on television or cable.

• Mind Pictures. The “theater of the mind” is a concept that we discussed earlier in this chapter. Only radio leaves it to the hearer to create the image conjured by the words.

FIGURE 8-1 Creativity, high rates, winners. This ad sounds like the description of sellers in Chapter 2, doesn’t it? It looks uniquely like an ad for a radio salesperson with the emphasis on promotions. Courtesy Chancellor Media’s KHKS. Used with permission.

“Radio’s unique attribute is intimacy with the customer,” says Gary Fries, president of the Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB). “We’re an extra member of everybody’s family. Our job is to market the relationship between radio and the listener through events, through concern about the safety of children, through involvement in listener lifestyles.”

• Virtually everybody in America listens to radio at some point during the average week. That fact leads the RAB to outline these benefits of radio as a medium.

• Radio reaches 76.5% of all consumers every day and 95.1 % every week.

• Radio reaches 57% of customers within an hour of making their purchase decision.

• Radio reaches newspaper readers and television viewers.

• The average person spends 3 hours and 18 minutes listening to the radio on an average weekday. On the weekend that increases to 5 hours and 45 minutes.

• Radio reaches 95.9% of Hispanics and 95.9% of African Americans weekly.

• Radio reaches 82.3% of adults in their cars in the typical week.

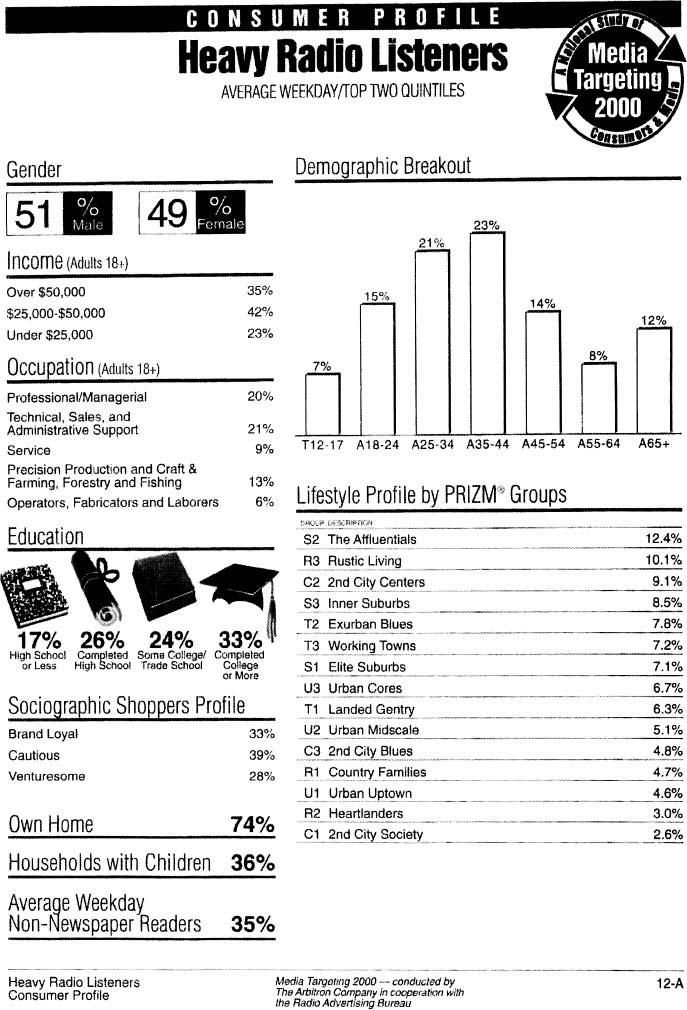

RAB also touts the percentages of people who typically listen to the radio while they’re working, running errands, or relaxing, including grocery shoppers, automobile buyers, financial customers, computer users, wine drinkers, restaurant customers, and a long list of other positive associations. (See Figure 8–2.)

In addition to the RAB’s list of radio’s benefits, there are other attributes that make radio attractive to advertisers:

FIGURE 8-2 I hope these profiles are as helpful to you as they are to me when I try to visualize just who uses either a medium or a product. The one thing to be said about a profile of radio users: it includes everybody! This profile is from Media Targeting 2000, a study conducted by the Arbitron Company in cooperation with the RAB. Used with permission from each organization.

• There’s a wide array of formats to reach listeners during a receptive state of mind, which can complement a specific advertising message.

• Radio allows delivery of its messages to multiple household members simultaneously and can deliver them 24 hours a day.

• Radio is advertiser-driven, that is, it’s intrusive. Listeners have to make a conscious effort not to hear a radio commercial.

• Radio advertising can be purchased nationally, regionally, or locally.

• Radio produces high-frequency levels, which enhance effective reach.

• It’s one of the most cost-efficient of the major media forms. Radio offers a proportionately low cost per commercial announcement as well as the lowest production cost of any medium.

• A radio commercial conjures the visual elements of a television commercial using imagery transfer; that is, reminding listeners of an image they’ve seen on television.

• The radio commercial can produce images not physically executable in other media forms by using the listener’s imagination.

On the other hand, there are also some negatives about advertising on the radio:

• Radio is often considered a “background” medium because the listener can do something else at the same time.

• Radio requires high levels of frequency in a schedule.

• The listener is not always able to take immediate physical action, such as calling an 800 number, depending on the listening location.

• There are high costs to purchase time on multiple stations in order to accumulate high levels of reach.

• Radio offers none of the visual or motion elements found in television.5

“I’ve always thought radio is a terrific medium,” says Bob Rose, vice president and media director for the Hal Riney & Partners New York office. “On paper, it’s a dream come true for a media planner. It’s efficient and it cumes a very broad reach over time, yet it has the ability to deliver more focused audiences as well.”

Rose was one of many ad agency executives interviewed by Radio Ink over a period of years. He told the magazine that his agency used radio for a variety of reasons: “We’ve used it to supplement television network under-delivery; we’ve used it as a stand-alone to deliver a campaign where other clients didn’t have money to be in television; and we’ve used it to hit specialized audiences as well.”

When Alec Gerster took over Grey Advertising’s media department in the early 1980s, it was the largest in New York. Later, as Grey’s executive vice president and director of media and programming services, he told Radio Ink that he found it “ironic” that “every account guy, media person, client, and creative team uses or listens to [radio] in some way, yet it’s not, by any means, one of the high top-of-mind media options.”

As late as the early 1990s, radio was still a difficult buy for a national advertiser. In 1993, Sean Fitzpatrick was vice-chairman and area manager for McCann-Erickson in Detroit. In another Radio Ink interview, he said, “The fact is that radio does a great job on the local level. Programming is extremely good, and the effectiveness of radio as a buy is very good. What’s totally stupid—and without measure in the media industry—is radio’s inability to sit down and create for itself a national sales platform. Radio makes it too difficult for the big-time advertiser to buy radio. On the other hand, you make it an easy local buy by cutting any kind of deal.”6

But just as he was saying those words in 1993, radio was changing. Gary Fries had assumed presidency of RAB and was creating the “national platform” that Fitzpatrick suggested. Trying to recover from a deep national recession, local radio stations were creating partnerships, local marketing agreements (LMAs), which linked the selling efforts of several stations. The stage was being set for the changes that reshaped the industry after the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (referred to later in this chapter as Telecom 96).

“Let the Deals Begin!” was the headline in Radio & Records in its first issue after Congress passed the new legislation that shifted media paradigms. “It’s buy, sell, or get out of the way,” Radio & Records said, as it reported on the first of what would be many consolidation moves after Telecom 96: Jacor Communications’ purchase of CitiCasters, Inc., and SFX Broadcasting’s acquisition of Prism Radio Partners. A harbinger of those purchases was the announcement that Group W and CBS would merge and create the largest group of radio stations in the country (“at least as of this week,” Radio and Records said).7

The 1996 changes meant that one company could own as many as eight radio stations in a single major market—more than could be controlled nationally under the old seven-station limit, which had lasted for decades. In the 1980s, the FCC expanded those limits to 12, then 18, then 20 stations. The new law set no upper limit to the number of radio stations one company could own.

Radio & Records’ joke about the biggest company “as of this week” became a reality quickly. Within 2 years of Telecom 96, CBS was eclipsed by Chancellor Media, which would control almost 500 stations. Jacor agreed to a merger with Clear Channel Communications, giving Clear Channel ownership of more than 450 stations.8

Here is a list of what any one company could own:

In a market with: |

A single entity can control up to this many stations: |

45 or more stations |

Up to 8, no more than 5 in the same service (AM or FM) |

30 to 44 stations |

Up to 7, no more than 4 in the same service |

15 to 29 stations |

Up to 6, no more than 4 in the same service |

14 or fewer stations |

Up to 5, no more than 3 in the same service |

In no case could a single owner control more than half of the stations in any market, regardless of size. The Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice decided that no single market radio ownership combination could exceed half of that market’s radio advertising revenue.

Writing in the Journal of Radio Studies, Christopher Sterling reminded us of a 1949 doctoral dissertation at Harvard University:

Nearly half a century ago, a young economist theorized that a single owner with five stations would provide more program diversity in a given market than would five separate owners. The owner of several stations would achieve a larger audience by providing five different formats appealing to five different audiences. The separate owners would duplicate the most popular formats in an effort to share the largest portion of the audience. Thanks to the 1996 amendments, we are already testing the theory under real market conditions.9

Radio found itself more viable than ever as an advertising medium after deregulation. Marketing consultant Jack Trout proclaimed, “The industry finally grows up” and offered congratulations to radio for “fast outgrowing its fragmented, almost cottage-industry status.” Trout addressed his advice to radio in a management article in Radio Ink:

1. Sell the medium, not your stations.

As a highly fragmented medium, just about all your energy and money was spent on beating up your direct competitors. Now that there’s some critical mass in many markets, perhaps we’ll begin to see some “my-medium-is-better-than-their-medium” efforts.

2. Make the medium easier to buy.

Buying television or newspapers is a snap compared to buying radio. Putting together a major buy usually entails having to deal with a parade of salespeople that spend a lot of time bad-mouthing other stations on the list.

How many stations can one radio operator own? As many as the company can acquire and operate, as long as the market by market rules are followed. That fact led to ownership numbers that were astonishing to anyone who remembered the previous limits. Chancellor Media’s proposed merger with Capstar Communications would mean 488 stations owned by one company, including stations in all of the top ten markets and in 17 of the top 20.

Here are the top ten radio owners, ranked by revenues, from Broadcasting & Cable, October 12, 1998:

Number Owned |

Estimated 1998 Revenues |

|

Chancellor Media |

488 |

$1,765,421,000 |

CBS, Inc. |

164 |

1,687,457,000 |

Clear Channel Communications |

453 |

1,240,644,000 |

ABC, Inc. |

35 |

339,822,000 |

Cox Broadcasting |

59 |

279,279,000 |

Entercom |

41 |

193,564,000 |

Heftel Broadcasting |

39 |

184,748,000 |

Emmis Communications |

16 |

171,538,000 |

Cumulus Media |

207 |

167,209,000 |

Susquehanna Radio |

22 |

152,475,000 |

Owning stations in the largest markets is the key to large revenue figures. Cumulus Media has a large station component, but since all but two of the company’s markets are ranked below 100, their revenues are less than a tenth of Chancellor’s. Emmis Communications, on the other hand, owns stations in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, giving their much smaller group considerable revenue clout.

3. Educate the users.

Radio is pure sound. To do good radio you have to understand how to use sound and sound effects. Unfortunately, most creative types are picture-oriented, not sound-oriented. Many are happy just to run the soundtracks from their TV commercials.

I’ve tried so hard not to use the word “paradigm” in this book, but I can’t hold back, especially when describing the new landscape of radio. The industry experienced a seismic paradigm shift after Telecom 96.

David Pearlman called radio’s new paradigm a “format change.” Pearlman, co-chief operating officer of American Radio Systems, leads a company that “changed formats.” It developed as one of the fastest-growing radio companies and then sold to CBS.

Rapid consolidation and mergers of radio companies was so difficult to track that the newsletter Inside Radio began publishing a weekly edition called “Who Owns What” to rank station ownership groups, their estimated revenues, numbers of stations owned, and estimated national audiences. The weekly scorecard ran 20 to 25 pages some weeks, listing individual stations figured in the station group totals based on that previous week’s buying, selling, and swapping. The top 50 markets were outlined with percentages of revenue controlled by each group with a cluster in that market. (See Figure 8–3.)

The pace of change was so rapid that when Sean Ross, editor of Billboard, was asked to appear at a regional radio conference and deliver the same speech he had presented just a few weeks before, Ross accepted the invitation but declined to use the same address. “None of it would be true,” he said. “That’s how fast things are changing.”10

FIGURE 8-3 You can’t tell the players without a scorecard. Radio’s daily newsletter Inside Radio introduced this weekly edition to document the rapid changes in the industry with mergers and station consolidation. ©1998 Inside Radio. Used with permission.

By the end of 1998, 71.4% of commercial radio stations were in some sort of consolidated clustering. The figures were over 75% in the largest (top 50) markets.11 This activity was revolutionary in a business where, as recently as 1992, no one was allowed to own more than two stations in any market.

The business outcome of deregulation was very positive for radio:

• Advertising revenues topped $13 billion in 1997, giving radio 7.1 % of total advertising dollars.

• Marginal signals were saved by combining sales with other stations to yield efficiencies.

• Companies gained additional inventory to sell by combining stations.

• The value of the inventory was increased with more sophisticated selling.

• Asset values and stockholder values of radio companies grew at exponential rates.

In fact, if you apply the measures that Tom Peters used in his 1982 book, In Search of Excellence, to radio companies after Telecom 96, most would show favorably. You’ll recall that Peters measured (1) compound asset growth, (2) compound equity growth, (3) average ratio of market value to book value, (4) average return on total capital, (5) average return on equity, and (6) average return on sales.12

Radio networks underwent the same revolutionary changes that local station operations experienced, thanks to a consolidating industry. Here comes that phrase “paradigm shift” again.

Paradigm Shift, Version One: Combine Forces

The first to merge were Westwood One Networks and CBS Radio Networks. Westwood already had a stable of brands to sell. It had its own long-form music networks with 24-hour country, rock, adult contemporary, and talk programming. Also in its stable were NBC Radio Network, CNN Radio, CNBC Business Radio, and Mutual News. The company added Fox News late in 1998 and announced the development of the Fox Radio Network.

By combining resources with CBS Radio, Westwood sold advertising for all the radio brands but ABC. The merger with CBS made Westwood the largest radio network. Mel Karmazin, CEO for both CBS and West-wood, used that fact to their advantage. “All we do is radio,” he told Manager’s Business Report. “We think that having a company that is a dedicated radio company has always been good for every industry. For [ABC owner] Disney, radio isn’t their first priority.”

Karmazin entered the network business in 1993 when his Infinity Broadcasting bought Unistar Networks. Unistar, producer of 24-hour music formats, later merged with Westwood One, producer of weekend programs and specials. At the time Karmazin told Broadcasting & Cable, “I’m a little surprised it took us so long to get into the network business. It’s definitely a business we’re going to stay in and expand in.” When Karmazin merged Infinity with Westinghouse and CBS in 1996, his words rang truer than ever.13

Paradigm Shift, Version Two: Create a New Network

The launch of the AMFM Networks, created by Chancellor Media at the beginning of 1998, was one of the largest new network debuts ever. (See Figure 8–4). It was made possible by designating inventory at the stations owned by Chancellor and its merger with Evergreen Media. Other stations owned by Capstar Partners also pledged inventory.14

The available commercial time was the linchpin. No other radio network delivered the top 10 markets the way AMFM could with their owned stations in those markets.

“Another benefit is the number of stations that we bring to the network radio pie that previously were unaffiliated with any other network,” AMFM senior vice president David Kantor, told Hitmakers. “In the past, network radio reached only about 65 percent of the United States Now, with us coming in, we anticipate that number will be in the mid-80s. It makes it a more viable national medium and hopefully will help us to bring in more dollars to network radio.”

In addition to spot inventories at key stations, AMFM signed Kasey Casern for a reincarnation of his American Top 40 radio show, which meant a defection by Casern from Westwood One. To staff the new AMFM Networks, Kantor hired personnel who had worked with him at ABC Radio when he was president of that network. AMFM launched with clout.

Paradigm Shift, Version Three: Own the Programming

Premiere had been in the network business for ten years before its merger with Jacor Communications in 1997. Premiere’s base was unlike most networks, however: it provided radio production services, Web site development, and Mediabase music monitoring services. The fact that Premiere provided those services in exchange for inventory at affiliated stations made their model resemble the traditional network model.

Premiere’s first long-form program was After MidNite, an all-night program for country stations, originating in Los Angeles. That program did not join the Premiere fold until January 1997. With the Jacor merger, Premiere created a programming powerhouse by combining Premiere products with the syndicators of Rush Limbaugh, Dr. Laura Schlessinger, Art Bell, Jim Rome, Michael Reagan, and Dr. Dean Edell—the biggest names in talk radio. (See Figure 8–5.)

While Premiere sold network inventory, the big money for those shows came from licensing fees paid by affiliates. Premiere walked a fine line between being a syndicator and being a network.15

“Old” is not bad. In referring to ABC, “old” means that ABC’s network configuration is more traditional than the others.

ABC’s Paul Harvey News and Comment was radio’s number-one rated program year after year. ABC had ten of the top ten programs and 19 of the top 20 in the fall 1997 RADAR (Radio’s All Dimension Audience Research, conducted by Statistical Research, Inc.). ABC offered top-of-the-hour news networks, 24-hour music formats, ESPN Sports, and specialty programs. They did some minor paradigm shifting of their own when they introduced The Tom Joyner Show, a live wake-up show aimed at African-American audiences.16

The Unchanging Paradigm: Selling Network Commercials

Radio network buying is generally done by the same high-level agency negotiators who buy network television. Just like TV sales, selling for a radio network requires patience and good negotiating skills. Oral skills are essential, since the seller of network radio time often makes sales presentations to groups of high-level advertising agency executives and their clients.

Warner and Buchman make this suggestion in Broadcast and Cable Selling:

Buying time on a radio network is a good way to introduce national advertisers to broadcast advertising, especially if they cannot afford network television. Agencies often encourage this type of developmental selling because the addition of network radio to an advertising plan often involves an increase in an overall advertising budget, on which the agency makes more money.

The real difference between selling radio network time and selling TV network time is the agency’s willingness to hear ideas about how to enhance a schedule at radio with value-added promotion. This difference can be a real selling point for radio.

FIGURE 8-4 The launch of AMFM Radio Networks brought major stations in the largest markets into the network radio fold. This ad listed 41 stations, but the combination of stations owned by Chancellor Media and Capstar Broadcast Partners totaled more than 500 outlets. Courtesy AMFM Networks. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-5 Premiere Radio Network touted its all-star lineup of personality talk shows with ads like this in radio trade publications. Used with permission.

Radio time and production cost so little compared to buying TV time and producing TV commercials. As Karmazin of CBS says, “General Motors spends more money buying yellow pads than its does in network radio. That’s the opportunity.”

There’s a fine line between network radio and syndicated radio. Some syndicators sell commercials to advertisers, some sell programming to stations, and some do both. (See Figure 8–7.)

The advent of computer-based wide area networks (WANs) allowed local station groups to create ad hoc networks of their own, sharing morning shows or other air talent. When they do that are they actually a network? Well, it’s networked, isn’t it? The phrases to use are “programming supplier” and “program service,” whether the discussion is about ABC, Westwood, or a true syndicator like SupeRadio, which provides weekly specials for contemporary music stations, a live morning show, and a long-form classical format. (See Figure 8–6.)

The United Stations Radio Networks have “networks” in their name, and they sell commercials like a network. At the station level, they’re seen as a programming supplier with a catalog of comedy services that morning personalities like to use and a line-up of weekend special programs, including some hosted by Dick Clark, a partner in United Stations. The company tried a series of daily talk shows, but decided to shift the affiliation burden to another company while retaining the rights to sell commercials in the shows.

“Network radio can be a complex medium to buy,” says Maureen Whyte, vice president of McCann-Erickson, who looks at both network buys and syndication buys for her national clients. She continues:

For adult buys (generally 18–49 and older), it is likely that the line networks will take up at least 50 percent of the gross rating points (GRPs) with the balance going to syndication. The older the target demographic group is, the more important the line networks are to the mix, due to sheer ratings strength.

For youth and young adult targets (12–34), it is likely that syndication will be used to reach the majority of the GRPs, with the balance going to the line networks.17

Whyte claims that the complexity of buying syndication comes in establishing exact clearance times. For example, a station might run a program in morning drive, but then clear the attached commercial in another daypart. Or a commercial that runs from 7 p.m. to midnight is classified as a 6 a.m. to midnight clearance.

“In spite of the nuances involved in evaluating syndicated properties, we believe that it is a vital part of the network radio marketplace,” Whyte says. That’s why networks and syndicators are sometimes difficult to distinguish.

In the September 1998 RADAR, Premiere Radio Networks was measured for the first time with four network configurations, covering a cumulative total of more than 2,200 stations. “Dr. Laura,” a Premiere program classified as syndication, was included in the measurement. Advertising agencies cheered because it was the first opportunity for accountability in radio syndication.

In Chapter 5 you learned that by the time an agency’s advertising schedule gets to the buyer, it’s too late to influence anything but cost per point. Sellers who call on agencies are most effective when they work the planners (who can make the decisions) as well as the buyers. Radio salespeople discovered that idea later than their colleagues in newspaper and print. To radio’s credit, the lesson was learned, and it benefited the industry overall.

Karen Ritchie raised eyebrows in the radio world in March 1993, when Radio Ink magazine quoted her blunt assessment: “Radio is doing a dreadful job, primarily because of the way it’s sold. … There has been absolutely no attention ever given to marketing or planning disciplines.”

FIGURE 8-7 The WOR Radio Network rides that fine line between network and syndicator. The company syndicates the talk shows from New York’s WOR and sells advertising like a network. This flyer touts the return of New York talker Bob Grant to WOR and to the WOR Network after his dismissal by WABC. Courtesy WOR Radio Network. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-6 It may not be a mix show or a countdown, but it is a syndicated show. Street Jam from syndicator SupeRadio, is designed for weekly play on contemporary stations. Courtesy SupeRadio. Used with permission.

At the time, Ritchie was senior vice president and director of media services at McCann-Erickson Worldwide, Detroit, and group media director for General Motors (GM) Worldwide. (Later she would gain notice as an expert in marketing to “Generation X” and publish a book on the subject.)

One radio organization that took Ritchie’s challenge seriously was the Detroit Radio Advertising Group (DRAG). First, they restructured their membership into “target teams” to broaden their work with ad agencies in Detroit, which control most of the automotive buys nationally. Second, they invited Ritchie to be the speaker at one of their breakfast meetings in June 1993. I was there to hear Ritchie issue her marketing challenge to the DRAG membership and again urge radio to take its message to media planners, not just buyers. Her example: Buick’s 1993 allocation for radio was 6% of the total budget. That figure could have been doubled, she said, if radio had sold her client on its industry as a whole.

For the Detroit meeting, Ritchie charted the changes in ad agencies from simple departmentalized functions to specialization with input at all levels. “Specialization in brands means not ‘food guys,’ but ‘hamburger guys,’” she says. “Specialization in media means someone who does great outdoor, someone else who does breakthrough television.”

Based on her experience handling GM accounts, Ritchie found radio salespeople in the early 1990s to be below par in knowledge of her client’s product. “It’s important to know that Buick doesn’t make Grand Am,” she joked. She was perfectly serious, however, describing print sellers (primarily magazine reps) as very knowledgeable in the client business. Is that why print gets almost 30% of the GM budget? Yes, she admitted.18

Here are Karen Ritchie’s rules for meeting with media planners:

1. Follow protocol Let the buyer know you’re meeting with the planners.

2. No surprises. Let the buyer know what you’ll do.

3. No sneak attacks. A meeting with the planner is no time to circumvent or embarrass the buyer.

4. Sell radio. Your station is secondary to the overall medium. Your business will benefit.

5. Bring ideas. Ideas and questions get planners involved.

DRAG’s target teams idea was an early response to radio’s need to show its sophisticated side. Led by DRAG president and COO Bill Burton, the organization developed teams for each of Detroit’s 21 major agencies. Each target team had a captain from a member radio station, station rep firm, or network. Team members worked with the captain to sell radio, not the individual stations, to the agencies. Burton is an ex-officio member of any team that needs him.

Burton outlined DRAG ’S target team objectives:

1. Get more radio dollars.

2. Get a larger share of the budget for radio.

3. Effectively sell client’s products using radio.

The Detroit group’s story is just one example. Other local radio organizations combined their forces to sell the medium, not just the individual stations. Accelerated efforts by the RAB accomplished the same ends on a national basis.

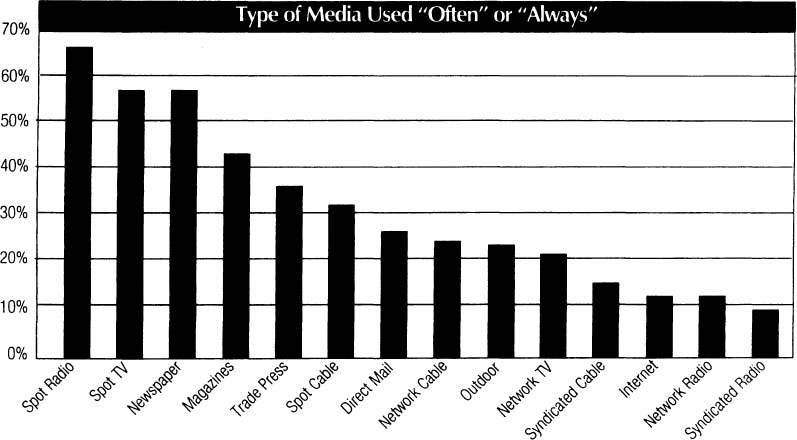

It worked! By 1997, perceptions at agencies had changed. There was such a change, in fact, that after a study of 200 ad agency media planners, Arbitron called radio “a planner’s best friend.” Specifically, the study referred to spot radio bought on a national basis. Two-thirds of the respondents to that study put spot radio at the top of a list of 14 different national media. Radio’s 66% score was followed by spot television and newspaper, both at 57%. (See Figure 8–8.) Planners who use radio for their clients tend to use it often, including radio as a regular component of their media mix. Only 12% of the planners surveyed said they rarely use spot radio.

FIGURE 8-8 For two-thirds of media planners surveyed by Arbitron, radio is at the top of the list as the medium they used “often” or “always.” The chart is from Arbitron Advertising News, May/June 1997. Used with permission.

Why radio? The planners liked the following benefits the most:

• The ability to target specific demos

• High frequency

• Creativity

• Short lead time with the ability to change messages

• Availability of both qualitative and quantitative data

• Superior cost alternative to television

On the other hand, planners criticized spot radio for not being as effective as they’d like in reach, which was a surprise in the study since reach is usually accepted as a strength of the medium. They also gave radio low marks because of lack of visuals.

The study was developed by Arbitron and conducted by Direct Marketing Results. It explored perceptions among planners of every available advertising medium and asked them to list their priorities when planning campaigns. To participate in the study, planners needed at least two years’ media planning experience and had to have used spot radio in a plan within the previous 6-month period.

Compared to Karen Ritchie’s deserved criticism just a few years before, the Arbitron study was good news for radio as an industry. The increase in national spot business in 1996 and 1997 and the robust revenue gains at radio generally also spoke well for radio’s improved selling efforts.19

Gary Fries tells his audiences, “We think we’re in the radio business, but we’re a bridge between the advertiser and the listener.” Fries carries the banner for radio to advertisers, radio station sales staffs, and broadcast conventions.

His mission is to help radio increase its advertising dollars. “We’re ahead of Yellow Pages, but still behind newspapers, magazines, and television in share of the dollar,” he reported to a group of Arkansas radio operators in 1997. (He made the speech many times, and I was his “opening act” on several occasions that year as we addressed the same groups.)

Fries credits consolidation with allowing failing stations to add new, niche formats “to raise the level of good, quality inventory.” Don’t discount timing: “Radio opened new inventory during a strong economy. If it had happened in 1989, we might not see the same results,” he said.20

What results we saw! Radio revenues from 1997 reached $13,646 billion dollars, by RAB count, which was $1.2 billion more than the previous year. That was the year radio broke through the 7% mark, capturing 7.1% of all advertising dollars in Mc-Cann-Erickson’s annual tally.

How can we increase that share? Fries’ answer: “Solve the problems of the advertiser. Become part of the marketing team of our advertisers.”

“What drives a radio station is localization,” said Charlie Colombo when he was president of Banner Radio, the New York-based sales representative firm. “Local personalities and local promotion make a station win in its market. The same thing makes an advertiser successful.” Colombo called radio “the pulse of the market.”21

So many local radio stations depend on local accounts for their livelihoods because local advertisers depend on the local stations to get messages to their customers. The smaller the market, the higher the percentage of local business on the station.

When I wrote the section in Chapter 5 about direct (or “retail”) selling, I really wanted to tout radio over all the other electronic media. To be fair to sellers of television, cable, and new media I didn’t. Now that I’m writing about radio, I can. Selling direct is radio’s great strength. Yes, my roots are in radio and that makes me partial to the medium. The majority of radio stations are in small towns, and that makes direct selling radio’s forte more than any other medium’s with the possible exception of newspaper.

Nowhere is the need for customer focus greater than in direct selling. The radio seller has to know enough about the advertiser’s business to get customers through the advertiser’s doors. The typical way to get to know the advertiser’s business is simply to ask. Next is to read trade journals in the advertiser’s field. Radio sellers have an additional advantage. If your station is an RAB member, that organization maintains remarkable resources on a variety of businesses.

Some radio sellers call agencies and ask “Do you have a buy for me?” or they call a direct account and ask “How many spots do you want?” If you believe in customer focus, you won’t be one of them.

Kerby Confer, chairman of Sinclair Communications’ radio division, says he was a 30-year-old disc jockey in Baltimore when sales representatives from his station would ask him to accompany them on sales calls. They liked Kerby’s presence because he was creative off the air as well as on.

“With the advertiser, I did my on-air bits and the salesperson just sat there,” he says. “I thought, hey, I can do my bits and ask for the order, too. This is show business, and we should be in show business in the client’s office as well as on the air.”

That realization started Confer on a sales career that expanded to include ownership of stations and running two national chains in radio’s consolidated environment. He continued to ask if he could go on sales calls with his local staff, to address the sales staff, and to lead creativity sessions. (It was Kerby’s “big deal pen” you read about in Chapter 2.)

“Advertisers see nothing but a shuffle of papers with rankers and other station descriptions,” Confer says. “Better to call a bicycle shop and say to the owner, There’s a bike shop in Memphis that doubled its business with this commercial.’ If you give ideas to increase business, you’ll own him.”22

Mike Bass was a client service representative for the Radio Advertising Bureau in Dallas when I spent the day exploring the resources they maintain for their 5,000 radio station clients.

The first call Mike fielded while I eavesdropped was from a salesperson in Milwaukee. She wanted information about indoor rock climbing so she could work up a proposal for a new health and fitness prospect at WXPT. Mike said he knew he had something and would try to find it quickly in the RAB’s computerized database.

He checked keywords: ’Amusement park.” No luck. Then, “Rock climbing.” Still no luck. He tried a few others, but couldn’t locate the information while the lady from Milwaukee was still on the phone.

“I’ll have to send that one to research,” he told me, visibly disappointed in himself. “I know we’ve got it, though.”

A few more calls came in. Valerie from WGGY in Wilkes Barre wanted to know what RAB had on file about banking, about beepers and pagers, and about selling to a local university. Mike found what she needed immediately and sent her articles from the database by fax while she was still on the phone with him.

Another call came in, this one from Hopper at a station in Guilford, New Hampshire, who wanted Simmons Research information on appliance purchase habits. A keystroke or two and that information was on its way.

Another client representative told Mike to try “health and fitness” for the indoor rock climbing articles. Sure enough, up came the information he had remembered. The seller from Milwaukee had waited only 7 minutes or so.

Mike fields 50 such requests on an average day and has logged as many as 121 in a single day. Mike and his cohorts are the research department for RAB-member radio salespeople who want to be customer-focused.

RAB’s “Instant Background” service alone covers hundreds of industries with two-page summaries of activity. Add to that the in-depth research on virtually any industry a radio sales representative might call on, and the organization provides radio with a staggering amount of information.

Most users talk to a client representative like Mike Bass and wait by their fax machines for only a few minutes for the data they need. RAB also maintains a huge Web presence with most of the information accessible by password only at www.rab.cmn.

How does the organization keep up with the businesses like the indoor rock climbing industry? It stays in the know by reading and clipping industry trade publications and by spotting related items from the consumer and business press. The research department (there are four people) reads more than 250 publications on a regular basis and adds data retrieved from Internet sites to add about 400 other sources.

Sales trainer Jim Taszarek agrees. “Leave your rankers in the car,” he says, advising against reams of research data that show your station a tenth of a point away from your competitor in the ratings. “Advertisers have tons of information, what they need is ideas. They’re looking for a great spot, a great campaign. They’re looking for an edge.”23

To demonstrate that you or your station is a resource for ideas, start with your presentation: attract attention. It takes creativity, an idea that sets your proposal apart as something special. Here are some good examples:

• The cake chart. A sales rep at KCCY Radio in Pueblo, Colorado, wanted to show the station’s audience with a pie chart. Instead, she used a “cake chart.” The prospect was presented with a round cake, with the station’s share graphically shown in the icing.

• The weakness. A Chattanooga seller presented a contest idea to a hamburger chain. He told the client that it was a great promotion that the station really believed in, but there was a weakness in it. He said he would describe the weakness at the end of the presentation, and maybe the client could help.

At the end of the presentation, the client was interested, but before he signed, he wanted to know the weakness. The seller replied, “We’re only asking $35,000 for this. It’s such a reasonable price you might not think we’re really serious about how good a promotion it is!”

• The punchline. GulfStar Communications’ Chris Wegmann tells the story of a one-sided game of telephone tag with a one-person agency when he managed a station in Pittsburgh. When there was no reply to his messages, Chris called the agency’s voice mail and recorded the setup to an intriguing joke. “Want the punch line? Call me.”

• A model sale. A Seattle sales manager couldn’t get a Nissan dealer to respond to a presentation, so he went to a hobby shop and bought a model truck kit. Once the model was built, it was delivered with a note: “If you’re interested in selling more of these, please call.”

• The homing pigeon. A friend of mine at an Atlanta station delivered a homing pigeon to a Buick dealer with a note: “I’ve been trying to see you with an excellent media campaign. Please put a time for an appointment in the capsule on the bird’s leg.” In a few days, my friend got a call from the owner of the bird. The car dealer was ready to meet.

• In the can. The presentations had been made, but KHFI in Austin was having trouble closing on the Coors account. Account Executive Peggy McCormick went to a costume shop and was “fitted” for a Coors can costume. Wearing it, she made one last presentation. And she got the order.

• Know when you’re whipped. A seller for our long-time client KFRG, in San Bernardino, California, presented a bull-whip to a buyer with a proposal, saying, “You’re going to beat me up on rates anyway!” That was the seller’s way of anticipating an objection and getting ready to neutralize it.24

In Chapter 1, I suggested that the presentation kits strewn on the floor of my office were a metaphor for the explosion of media options available for the audience. That same littered floor was also a metaphor for the options available to advertisers. An important consideration for radio sellers is how good do your presentation materials look?

Jim Taszarek reminds audiences at industry conferences that “We’re competing with everybody who does business with our clients. Not just other radio stations or media outlets.” That means your prospect or client will judge your media kit against national magazines, appliance brochures, and graphics from their local printer. If the local cable salesperson has access to the media kits for each of the networks on the system, that advertiser—your prospectwill have seen some of the glitzy presentations I mentioned earlier.

Now how good do your station’s presentation materials look?

So many radio stations I’ve encountered use photocopied presentations that look like they were photocopied. A Xerox salesperson would be embarrassed because they not only show the station in bad light, but they also show the station’s copier to be in bad repair.

No radio station needs to spend the kind of money that the national networks spend on their kits, but every station owes it to its clients (and to its sales staff) to look good. With the technology of desktop publishing, there’s no reason to look anything but professional.

Next, put the presentation in client terms. As Mike Mahone, executive vice president of RAB says, “Start from the prospect’s perception of reality (not our opinion of how it is or ought to be), and use those perceptions as the foundation of the entire proposal.” Like other sellers, Mahone uses the prospect’s logo on the cover of presentations. He suggests that it should be the “largest item on the page, demonstrating right up front that the subject of the proposal is going to be the client—that the client will be the most important entity in the discourse that will follow.”25

In the “Get Wet & Win!!” proposal in Figures 8-9 through 8-11, you see that the promotion idea, the name Sea Doo, and the picture of the Sea Doo craft are prominent. Furthermore, every page is headlined with the Sea Doo name. The proposal is not elaborate, but it looks good (even in this black-and-white rendition). The typeface makes it very clear and readable.

Jim Taszarek takes presentations beyond the “logo on the cover” idea and suggests a “client-based title” on the presentation as well. He uses “Full Boat Monday Night” as an example. “‘Full Boat’ means a car loaded with accessories at a maximum profit for the dealer. Monday night is the worst selling night of the week,” says Taszarek. Put those two together, and you have the attention of an auto dealer.

To be completely customer-focused, Taszarek suggests avoiding the words “pitch” or “presentation.” “That’s what it is for us,” he says. “Let’s use words with client benefits, what it’ll do for them, the people with the money.” His suggestions include, “a plan,” “an advertising blueprint,” and “a radio advertising flow chart.”

FIGURE 8-9 Putting the client first is important for any presentation or proposal. Here you have to read the entire cover to see that this proposal is from Nationwide Communications. This is from “Nontraditional Revenue Proposals” collected by RAB and is used with permission.

FIGURE 8-10 This proposal ties several sponsors together. Sea Doo is an obvious one. Read carefully and you find Hawaiian Tropic sun care products and Sea World amusement park, too. Not until you get to the third panel of the presentation do you see that Nationwide’s WGAR is the station sponsor. Courtesy RAB. Used with permission.

I won’t embarrass the station by using call letters, but a station in a small, Arbitron-rated market sent me a presentation package that demonstrates what not to do. First of all, the station talked about itself and about nothing else. The presentation was stacked this way:

• The power (50,000 watts) and tower height (500 feet)

• The name of the family business that runs the station

• The programming consultant they hired

• The fact that they play country music

• The fact that they are committed to assisting area businesses to develop an effective overall marketing plan

Finally! The last point is all that the customer cares about.

The points about the power and the tower in the list should be in customer terms: how many of the advertiser’s customers can hear the station? How wide a coverage area can the client draw customers from? The consultant is irrelevant to the advertiser. Country music is an important point, but how does that relate to the advertiser? In this particular case, the whole area loved country music. That means the station is able to target the very people who would visit the advertiser’s store, which is a point they should have included.

You get the idea: customer first. The radio station is a conduit for the message between the advertiser and the people who will buy the advertiser’s product or service.

FIGURE 8-11 Here’s what each party has to do to participate in the promotion. Sea Doo’s investment was in radio time and in the Sea Doo watercraft. (Note: “POP” is retail-speak for “point of purchase.”) Courtesy RAB. Used with permission.

People spend more time with radio than with any other medium. (See Figure 8–12.) You saw among radio’s strengths the ability to target certain listener groups through formatting. A Top 40 station will deliver 18-to 34-year-old listeners. A news and talk station will deliver listeners 35 and older. Adult contemporary stations tend to attract women, while rock stations typically attract men.

Format differences are of tremendous advantage to advertisers who target their buys and their messages to the specific audiences of each station. For example, adult contemporary stations are proven to deliver clients for medical offices, home builders, and grocery stores. News and talk stations deliver customers for cell phone companies, auto dealers, and financial services.

FIGURE 8-12 As a radio guy, I hope the headline remains true for a long time. Because television captures attention in the evening hours, RAB tends to use 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. figures for radio. Except for teens 12 to 17 (the second graph), radio leads. From Media Targeting 2000, conducted by the Arbitron Company in cooperation with RAB. Used with permission from each organization.

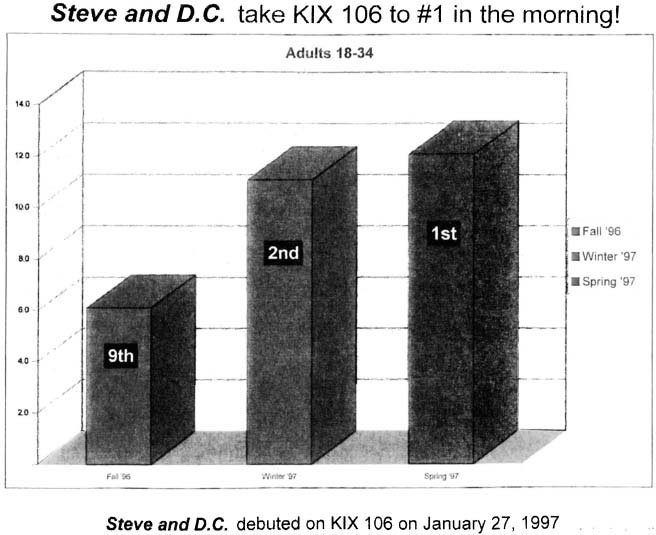

Listeners are generally in a positive frame of mind when they’ve chosen their favorite music or radio personality for companionship. The radio commercial uses that environment to transfer positive feelings to the product or service being advertised. (See Figure 8–13.)

“I believe that the best commercials nearly always make people feel that the advertiser is talking directly to them,” says Tony Schwartz in Media: The Second God. Schwartz is one of the best practitioners of the radio advertising craft. He calls commercials a form of narrowcasting:

FIGURE 8-13 To show radio’s targetability, here’s a chart of the growth of the syndicated morning show “Steve and D. C.” and the impact it had on adults 18 to 34 on KIX 106 (WKKX) in St. Louis in just three ratings periods. With radio, any demographic group can be targeted with positive effect. Courtesy SupeRadio. Used with permission.

An advertiser … is only interested in that part of the audience that has a need for his product or may become interested in it. To this end, he studies the distribution pattern of his product, selects stations that can reach his potential audience in that distribution area and tries to determine the most cost-effective way of doing this.

One of the most fruitful uses of radio, from an advertiser’s standpoint, is narrowcasting (as opposed to broadcasting). For instance, if we want to reach the elderly, we buy time on Station A. We reach teenagers on Station B, young blacks on Station C, Hispanics on Station D, jazz buffs on Station F, news hounds on Station G. Analyzing an audience along a different dimension, we may learn that 69 percent of Station H’s listeners read the Daily News, while 65 percent of Station I’s listeners read The New York Times. During the morning, 80 percent of Station J’s listeners are in their cars, most of them driving to work.26

Those two paragraphs are the best short course in selling radio I’ve ever read!

Schwartz believes so much in the narrowcasting aspect of radio that he has bought time on stations to reach only one person! In one instance, he designed a commercial to reach only the president of a major automobile company who did not believe in using radio advertising. The purpose of the campaign was to change the man’s mind. They found out what station he listened to on his drive to work and bought a highly targeted spot that said people think more consciously about automobiles when they are driving automobiles.

“He listened,” Schwartz says, “because we discussed his concerns, his aims, his problems. He must have felt these commercials were talking to him, even though it probably never entered his mind that he was the only person we were interested in talking to.” The campaign worked: someone from the automobile company called the phone number listed in the commercial. Six other companies also called!

Schwartz was able to target his audience of one by finding out the man’s favorite radio station. Everybody has at least one favorite station, and often they choose two or more favorites depending on their mood or activity. Arbitron indicates that the average listener over 12 years of age listens to 4.1 stations over the course of a week. That number varies by format. Listeners who prefer country stations, for example, listen to only 3.7 total stations; those who prefer sports stations listen to 4.4 total stations. The more loyal a listener is to any one station, the fewer total stations they use.

Billboard lists 17 distinct radio formats. Arbitron uses 38 different format designations. Because Billboard serves the music industry as well as the radio industry, their divisions are more music based. Billboard, for example, combines any station that deals in news, talk, or information into one category. Arbitron separates them into all news, news/talk/information, talk/personality, and all sports. Arbitron also separates adult contemporary, soft adult contemporary, hot adult contemporary, modern adult contemporary, urban adult contemporary, and easy listening. Billboard uses only two designations, adult contemporary and urban adult contemporary (Billboard used “Easy Listening” until early 1996.)27

FIGURE 8-14 Not only does radio target specifically by demographic and by format, but stations look for sellers who are experienced in specific formats. Courtesy Clear Channel, South Florida. Used with permission.

Arbitron’s categorization is more exact than Billboard’s simply because Arbitron shows the greater diversity. Even Arbitron’s designations cannot show the differences between Spanish contemporary stations in Miami, Houston, and Los Angeles, although Arbitron does separate urban oldies from rhythm & blues. The point here is not to find fault with the categorization but to demonstrate that there are lots of radio formats and lots of subsets to each format.

The major formats, found in virtually every market, are adult contemporary, country, contemporary hits (also called CHR and Top 40), oldies, and news/talk. (See Figure 8–14.) The more varied the makeup of the market, the more permutations you’ll find on the air. That’s when formats begin to split into smaller niches. For instance, “oldies” might mean the early days of rock and roll from the late 1950s, the Beatles-based 1960s, or the 1970s.

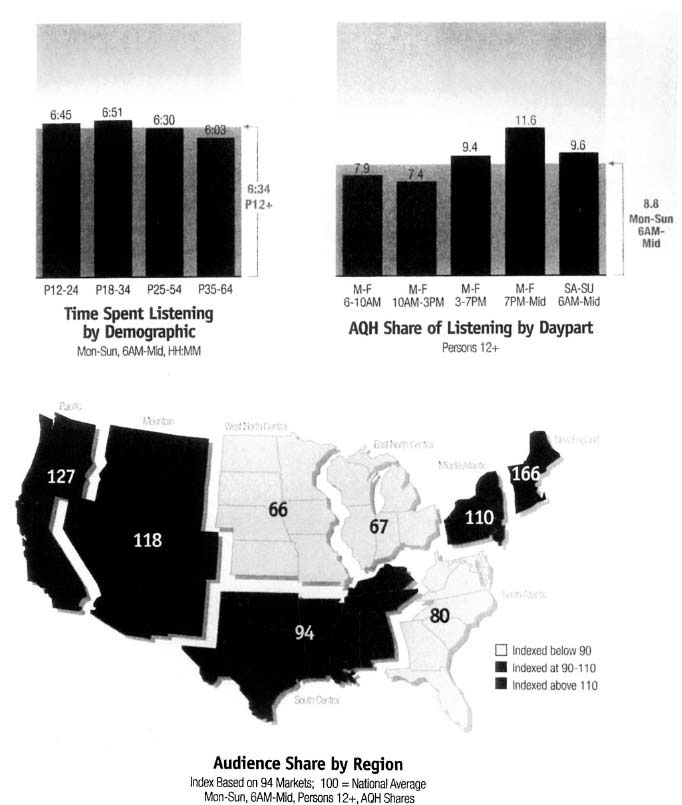

FIGURE 8-15 The Top 40 format was most popular in New England with the West Coast second in this analysis from 1997 Arbitron surveys. The audience profile is primarily teens to 34, and the audience is 58% women. The graph in the upper right shows that nighttime is prime time for Top 40 radio. The information is from Arbitron’s Radio Today: How America Listens to Radio, 1997 edition. ©1997 The Arbitron Company, and used with permission.

FIGURE 8-16 Here’s the same analysis for the news/talk format. For ease of demonstration, this category includes the all-news, news/talk/information, talk/personality, and all-sports formats. This is quite a contrast to the Top 40 analysis at Figure 8–15. The audience is substantially older and 56% male. The largest shares are in morning drive. The only similarity to the Top 40 graph is the high index of listeners in New England.

FIGURE 8-17 Here you can see real differences again. The largest audience appeal for the religious format is in the Southwest and the Southeast, while the lowest is in New England and the Mountain regions. The audience is made up of two-thirds women, mostly 25 and older, but the shares are very low. In this analysis, the religious format includes stations with preachers and teaching programs as well as those with Christian music formats.

The further into the 70s the sound gets, the more likely the station will call itself “classic hits.” Please don’t confuse “classic hits” with “classic rock,” no matter how subtle the difference in sound to your ears. (It’s like asking your parents to get the difference between house and industrial music, which are too narrow individually to base radio formats on. As targeted as radio is, there’s still a need for audiences large enough to be of value to advertisers.)

Formats vary by region, too. There are fewer country stations in the Northeast than there are in the Southeast and Southwest because the audience base is not as strong. In Figures 8-15 through 8-17, I’ve used three Arbitron analyses that show the differences in the top-40, news/talk, and religious formats by audience profile and by region.

Every format shows this type of regional difference. Many will have differences from city to city, even when the cities are close together. For example, the top 40 station in Houston, KRBE, is very mainstream in its sound, which is radically different from the sultry rhythms of KTFM in San Antonio, just 185 miles west on Interstate 10.

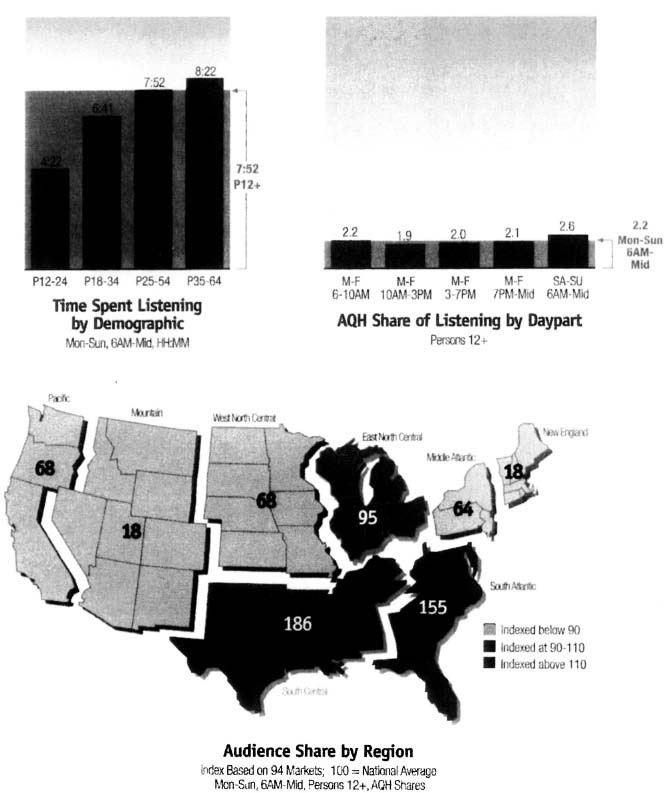

Good news from Arbitron about radio usage at work: during the average quarter hour, 40% of full-time employees are listening to radio. Of those, 65% say they are more likely to listen to radio at work than they are to read a newspaper (39%), surf the Internet (16%), or watch television (11 %). Although the boss chooses the station in 48% of work places, 43% say they typically listen alone and choose their own station. Another 13% listen in groups of ten or more. Of those, 49% make a group decision about the station.

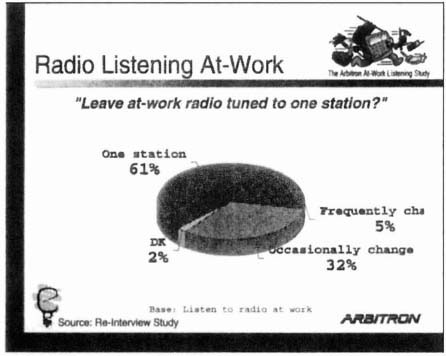

Almost 80% choose the station they listen to based on the kind of music it plays. The amount of music also comes into play for almost 60% of respondents. Most (61 %) say their office is tuned to one station all through the day. (See Figure 8–18.)

There are assumptions about listening at work that the study countered:

• “9 to 5” is a fiction. Only 4% of workers begin and end their workday at those times.

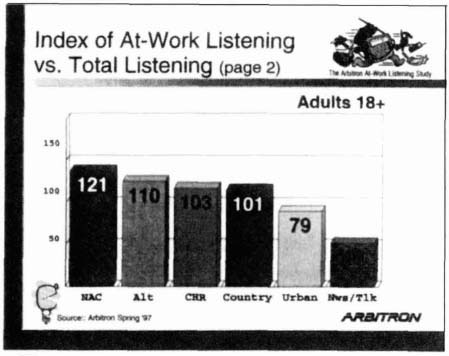

• “At work” does not mean at the “office.” Only 42% were at an office. Another 42% were indoors but not in an office setting.

• Adult contemporary formats do well in the workplace, but they don’t have an exclusive hold. Only urban and news talk score below an index of 100. (See Figures 8-19 and 8-20.)

• People are not forced to listen to stations they wouldn’t choose on their own.

The Arbitron Company and Edison Media Research conducted the study in 1997 by reinterviewing Arbitron diary keepers.”28,29

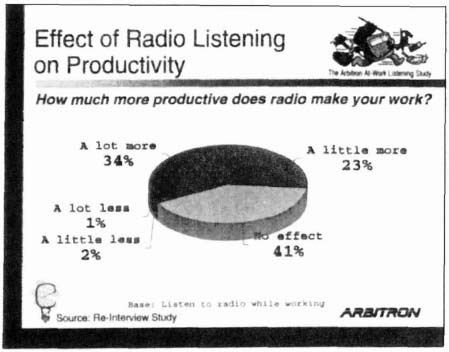

A real selling point for radio in the work place is the fact that almost 60% of the respondents say that listening to radio while working improves their productivity. (See Figure 8–21.)

FIGURE 8-18 People listening to radio at work tune to one station and leave it there, according to “Radio Goes to Work, the Arbitron At-Work Listening Study.” That’s good news for radio. Courtesy the Arbitron Company. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-19 The myth was that adult contemporary formats work best in the workplace, but Arbitron’s atwork study indicated otherwise. With the average at 100, you can see the impact each format has on adults 18 and over. Courtesy’ the Arbitron Company. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-20 Only urban and news/talk score below the average for at-work listening. Courtesy the Arbitron Company. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-21 Bosses all over America should love this news: radio makes workers more productive. At least workers think so and told the Arbitron at-work study so. Courtesy the Arbitron Company. Used with permission.

As you visit advertising agencies, you might encounter a sign on the wall in a buyer’s office: “Torture numbers and they’ll tell you anything.” It’s a way to put some fun into an otherwise serious business: buying efficiency through ratings points. Television’s phrase, “spots and dots,” is sometimes applied to radio when selling becomes meeting cost-per-point (CPP) or cost-per-thousand (CPM) goals. Agencies like to “torture the numbers.”

Buying “by the numbers” is the worst way to purchase time on radio. Radio’s inherent targetability should prompt agencies to buy audiences, but some agencies just don’t take the time to learn the subtle differences. (That’s what sellers are for, after all.) The typical Arbitron ranker might show 20 or more radio stations with what looks on the surface like the same shares. What buyer can make good sense of it?

“Sooner or later all selling comes down to eyeball-to-eyeball, mind-to-mind, person-to-person communication,” says Wayne Cornils in the foreword to Michael Keith’s Selling Radio Direct. Cornils, a former RAB and NAB executive, continued:

In advertising, and especially radio, there is a fringe which would reduce the profession to a pseudo-science of computer generated numbers.

Computer-driven robots build cars, but people sell cars. Computer software programs design and build computers, but men and women still sell computers.

Radio stations, like people, have individual personalities, and personalities don’t compute very well. The subtle differences between stations, markets, on-air talent, and promotion and marketing support are difficult—if not impossible—to accurately portray in computer language.

Computer systems such as the optimizers that agencies use to buy TV time (you read about them in Chapter 5) are not nearly so effective in radio. They may make a buy efficient, but they cannot make the buy practical. Using gross rating points (GRPs) to buy radio does not take into consideration whether the schedule can achieve results for the advertiser, only whether enough bodies will be reached by the commercial.

GRPs are useful in television because they relate directly to the number of viewers of a program. Advertisers who buy television know that the ratings apply to specific programs and that importance of time spent with a program is minimal. Television is measured in one dimension: household rating points.

Radio is measured in broad dayparts, and time spent listening is vital to radio ratings. The longer the listening time, the higher the share. Radio is measured in two dimensions: cume and average quarter hour.

GRPs are calculated one of two ways:

1. Multiply the number of spots by the average quarter hour rating, such as 20 spots running on a station with a 2 rating gets you 40 GRPs.

2. Multiply the total reach of the schedule, expressed as a percentage, by the average frequency.

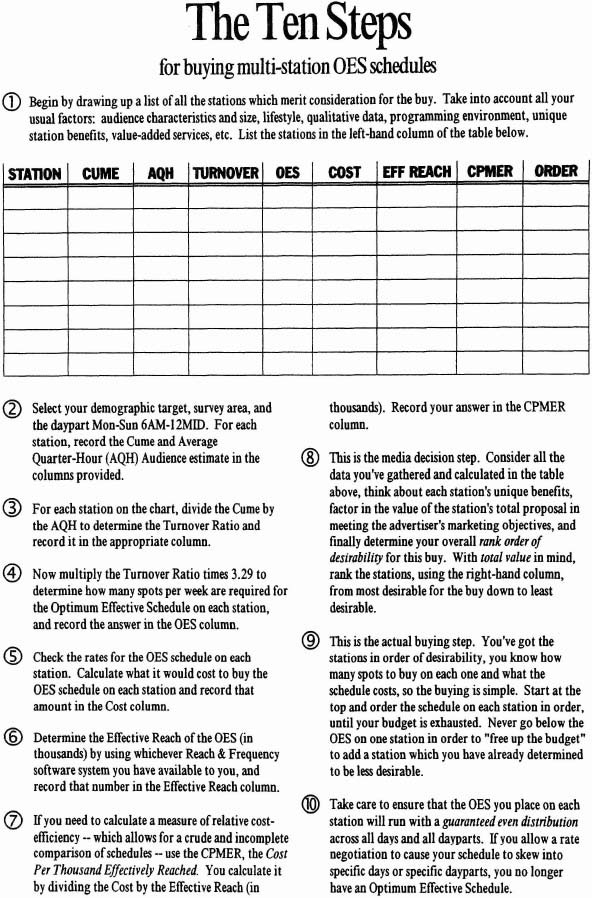

It’s good math, but it’s bad buying because GRPs conceal valuable information about reach and frequency. In Radio Advertising’s Missing Ingredient: The Optimum Effective Scheduling System, Steve Marx and Pierre Bouvard use this example of how four radically different schedules can each produce 100 GRPs:

Market Reach |

Frequency |

GRPs |

|

Schedule A |

100% |

1 time |

100 |

Schedule B |

50% |

2 times |

100 |

Schedule C |

25% |

4 times |

100 |

Schedule D |

1% |

100 times |

100 |

Schedule A will have virtually no impact, and Schedule D will make 1% of the market annoyed at hearing the commercial too many times!

CPP buys create the same danger for advertisers because CPP is based on GRP measurements. CPP calculations take into account only two factors—audience size and spot rate—not who is reached and not the value of the audience in terms of potential buying.

Marx and Bouvard reacted to CPP buys this way:

Imagine if the sole criterion in buying a new car was the average cost per part! Or if the determining criterion on your next clothes shopping trip were the average cost per thread! Would you decide on a college education just by looking at the average cost per book?

Sounds pretty silly, doesn’t it? So why do we allow radio to be bought and sold this way? Cost Per Point is a bean-counting exercise that misses the only important issue: will this schedule generate results?!30

Early in my radio career, stories circulated in the industry about agency buyers who bought only “by the numbers” and accidentally ordered schedules for suntan lotions on stations targeted to African-American audiences. I don’t know if the stories were true, but they reinforced the point of radio’s unique targetability. The audience of any station will have enough in common that effective (and studied) placement of commercials should deliver results.

Jim Taszarek’s training to his clients’ sales departments suggests three points to offset CPP or CPM buys: he uses the letters “CPI,” for “cume, profile, and ideas.” Taszarek feels that each presentation should show the station’s cume, a profile of how that cume fits with the product the buyer wants to advertise, and an idea that gives the station value beyond its numbers.

“I tried it once. It didn’t work.”

At some time in your selling career, you’ll hear those seven words. In Chapter 2, you learned to answer and neutralize objections, and you’ll recognize that as one of them. Your first response is to probe for more information. Explore the likely causes of disappointment.

“Disappointment” is the key word here. Often “It didn’t work” translates into “It didn’t meet my expectations.” A variety of factors determine the success or failure of a schedule in any medium, and advertiser expectations is first among them. Others are the marketing strategy, the competitive environment, the copy concept, and the medium chosen to carry the message.

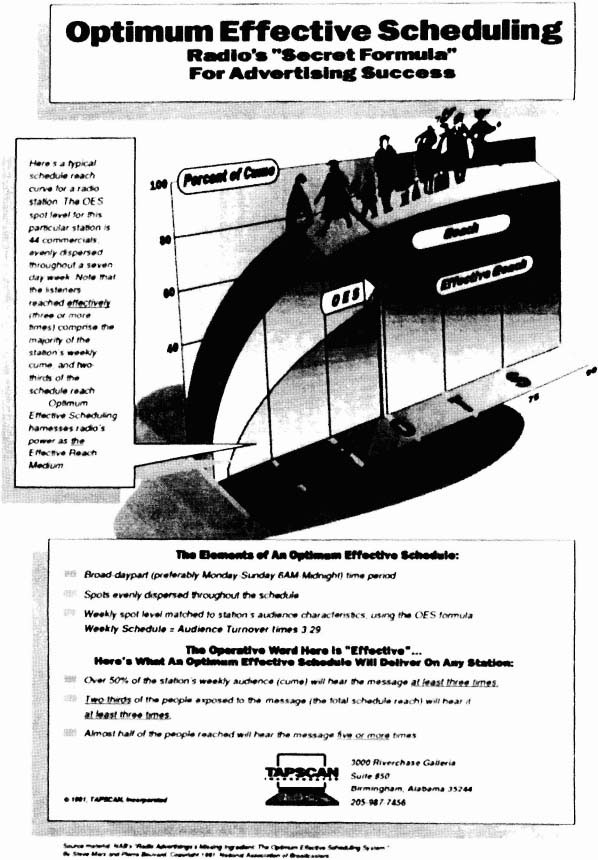

According to Steve Marx and Pierre Bouvard, one more factor was long overlooked in radio: scheduling. Marx is president of the Tampa-based Center for Sales Strategy. Bouvard is general manager, radio, at the Arbitron Company. Together they created the Optimum Effective Scheduling System (OES), which “opened the eyes of thousands of advertisers (and radio salespeople) to the awesome marketing power of the world’s most pervasive medium,” according to Gary Fries of the RAB.

In their OES book, published by the NAB, Marx and Bouvard reported on an NAB study “that points clearly to the fact that the vast majority of radio schedules purchased today either contain too few announcements or they’re spread over too long a period to generate the bang necessary to create a profitable return on investment for the advertiser.”

As far back as I can remember (mid-1960s or so), radio commercial schedules used increments of 6, 12, and 18 spots per week. Twenty-four spots per week was termed a “saturation plan.” No one seems to know why those numbers were chosen, although it may be a product of accommodating budgets of small businesses in small towns. Other mass media have traditionally used a high unit count per schedule. Television, for example, schedules two spots for the same client in a single commercial pod to double the frequency.

Marx and Bouvard called radio’s low unit count “a strange quirk of fate” and set out to create a more effective plan. To do so, they analyzed the schedules of WYAY-FM in Atlanta, a station owned at the time by New City Communications, the company that founded Marx’s Center for Sales Strategy. (See Figure 8–22.) They discovered that of all the commercial schedules run on WYAY, 48% had low spot loads. Those with low spot loads accounted for only 4% of schedules described as “successful” by the clients. Schedules with medium spot loads accounted for 41 % of all schedules and 46% of success claims.

FIGURE 8-22 When Steve Marx and Pierre Bouvard studied advertiser schedules on Atlanta’s WYAY, they discovered that only 11 % of the spot schedules resulted in 50% of the claims of success from advertisers. That prompted them to maximize radio’s reach and frequency with the Optimum Effective Scheduling (OES) formula. Courtesy NAB. Used with permission.

The numbers that made them take notice were the schedules with high spot loads (the OES schedules, as they defined them). They accounted for only 11 % of all schedules, but were responsible for 50% of claims of success.

“Our particular research approach at WYAY was not designed to find every success story,” Marx and Bouvard write, “but it did clearly demonstrate that Optimum Effective Schedules were more than 8 times as likely to produce impressive results for the advertiser.” (That’s their emphasis.)

Two factors for advertising in electronic media are reach and frequency. Reach is the head count of how many people are exposed to a message; frequency is the measure of how many times the average person is exposed to the message. Before the erosion of TV shares, television was considered the reach medium, and radio was the frequency medium.

In radio, there’s a delicate balance between reach and frequency. To get more reach, you may have to sacrifice frequency. By boosting frequency, you lose reach. Marx and Bouvard attempted to find a real number they called “effective reach,” which is just those people reached often enough for the advertising to be effective.

Advertising has long believed in the frequency of three theory: that three exposures to a message achieves the desired effect. There’s evidence to support the idea:

• Mike Naples’ benchmark book Effective Frequency demonstrated that one exposure of an advertisement “has little or no effect.”

• General Electric’s Dr. Herbert Krugman measured the difference between the first, second, and third exposures to advertising and concluded that the third exposure is the earliest point at which the human mind takes action.

• In Chapter 6, you read Joe Ostrow’s remarks about how a variety of frequencies is required to achieve different strategies.

So Marx and Bouvard added an important element to frequency: frequency over time. They recommended a minimum of three exposures within a week’s time. The number of exposures needed to accomplish that goal “is at a different weekly spot level for any given station, daypart, audience target, and survey period,” they said.

The essential number in their OES formula is the station’s turnover ratio, which is the mathematical comparison of cume and average quarter hour. Divide cume by AQH to yield the turnover:

![]()

Marx and Bouvard relate turnover to a library and a convenience store. The library has low turnover, in that a few people come in and stay a while. The convenience store, on the other hand, has lots of people coming in for brief stays. “If you were to broadcast advertising inside each of these locations, you might want to repeat the message more frequently inside the convenience store, right?” they say.

Compare that to radio stations: a station with high cume and a low average quarter hour has a high turnover (such as all news stations, where people tune in to get a quick update). A station with a low cume and high AQH has a low turnover (a classical music station, for example). You’d want to use more commercials in a schedule on the station with the high turnover.

To arrive at a formula to make OES as effective as its name implies, Marx and Bouvard settled on a frequency just above the magic number three: 3.29. That number is based both on research by the Katz Radio and Katz Television representative firms in the 1980s and on the reach-and-frequency formula developed by Westinghouse Broadcasting in the 1960s (known as “Westinghouse math”).

Marx and Bouvard added their own empirical evidence after applying 3.29 as a constant to their OES formula. It was further confirmed by a NAB study by Coleman Research (for whom Bouvard worked when the study was conducted).

The number 3.29 is a point on a graph where total reach and effective reach begin to separate. The total reach becomes wasted against the effective numbers of listeners who will hear the commercial often enough to be motivated by it. Figure 8–23 makes this clear.

What’s needed for an OES schedule? Figures 8-24 and 8-25 give you specifics. The formula is turnover multiplied by 3.29 to yield the number of commercials needed to effectively reach the station’s audience and create a success story for the advertiser. For example:

You can see that a station whose cume turns over often needs considerably more units in a schedule to effectively reach its target audience with a message.

Stations that do not subscribe to ratings services and have no access to their specific turnover ratios can use national averages for their specific format. The averages are published from time to time by Arbitron and are also available from national station representative firms. Usually the radio trade publications carry the national average turnover when it’s released.

FIGURE 8-23 The difference between total reach and effective reach is clear in this graph of an OES schedule from Tapscan, one of the software providers for radio sales. The OES level for this particular station is 44 commercials. Tapscan provides this graphic for radio sellers to add to their presentations to illustrate the OES concept.

FIGURE 8-24 A one-page summary on how to calculate an OES for radio. Authors Steve Marx and Pierre Bouvard urge buyers of their NAB book to photocopy the summary and distribute it to staff and clients. Courtesy NAB. Used with permission.

FIGURE 8-25 An OES worksheet from Radio’s Missing Ingredient: The Optimum Effective Scheduling System by Steve Marx and Pierre Bouvard. Courtesy NAB. Used with permission.

Radio salespeople should take advantage of the medium’s greatest strength and play commercials for potential clients. By using what radio does best—provide interesting sound—the seller has the opportunity to engage the imagination of the retailer with a commercial for that advertiser’s store. This type of commercial is called a “spec spot” because it is truly speculative.

Rarely do clients buy on the spec spot alone, but it has happened, says Michael Keith in Selling Radio Direct: “A spec spot should never (or rarely) be the plan itself but rather an element of the plan. In other words, design a package you know will do the job for the client, then use the spec spot to seal the deal.”

Using a spec spot after the needs analysis interview shows the prospect that you’ve understood what was said. It also demonstrates the skills of your station in turning out imaginative copy and effective audio production.

The best context for a spec spot is your station, so include a brief sample of the station’s sound with the spot. Let the client or prospect hear the way their commercial will actually be heard on the air.

Maureen Bulley, president of the Radio Store, a creative consulting firm, suggests rewarding everyone involved in the production of a spec spot when the spot results in new business. “The writer, producer, and voice-over talent—as well as sales reps—should be compensated for their contribution to the successful new business pitch,” she wrote in Radio Ink.31