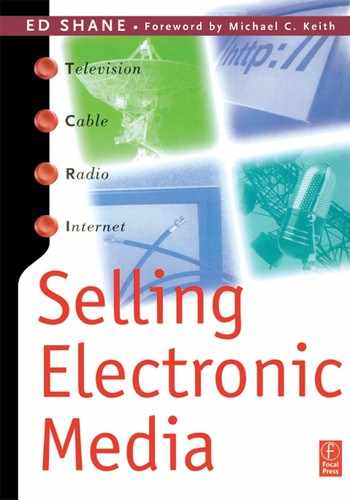

The first “sales training” I ever received came in 1968 when I was named program director of a radio station in Atlanta, Georgia. The general manager who hired me showed me a poster of “the man in the chair,” the grumpy old codger shown in Figure 1–1. The expressionless stare was chilling; the caption was as brutal as the man’s eyes.

“The man in the chair” began as an ad campaign for Business Week and other McGraw-Hill publications in 1958. It was named one of the top ten ads that year by Advertising Age. The campaign was updated in 1968, again in 1979, and yet again in 1996, with different people in the chair. Ultimately, it was translated into French, Russian, German, Italian, and Chinese.

In my 1968 experience, I heard the message in plain English. The problem with selling, my new boss explained, is that not every prospect makes it as easy as the “man in the chair.”

“Easy?” I asked.

Yes. The “man in the chair” ad could refer to any product. Further, it contained a straightforward litany of objections, ready to meet with information from a well-prepared seller.

Why did I need to hear that? I had just taken a job as a product guy at a radio station. I was not expected to sell advertising time, was I? Frankly, I hoped not. All of my exposure to selling anything prior to that day had been observing high pressure sales types who had tried to sell my parents something they didn’t need and couldn’t afford. In my mind, “sales” was charged with negative perceptions and evoked visions of diamond pinky rings and clouds of cigar smoke from overweight men who tricked people out of their savings.

My new boss called those salespeople “vultures” and said he didn’t think his sales staff acted that way. As I worked with them, I discovered that he was right. That staff cared about their customers and worked hard to make sure the clients got benefits from advertising on our station.

My boss told me that my job was to understand the challenges that my station’s salespeople were facing when they hit the streets every day. Also, I was to join the sales reps to meet with clients and talk about a product I knew better than the salespeople did.

Later, I would learn much more about sales—information that sellers in every field call “the basics,” but I didn’t know that then. Who knew then that prospecting and qualifying, analyzing needs and developing solutions, continuing service after the sale, and building relationships would be so important? Sure, the sellers did. Now the programming guy would know, too.

FIGURE 1-1 The Man in the Chair. A classic statement about sales and selling, originally an ad for Business Week magazine. © McGraw-Hill Companies. Used with permission.

I was fortunate to have been given a taste of the basics of selling early in my career. I felt I had been brought into an elite circle that gave me insight into the business. This insight led to my understanding of the way media works—not just radio, but media generally. It deepened my desire to be a student of media.

Ultimately, it also led to the opportunity to carry a list, to manage radio stations, and to found and manage my own company, Shane Media Services. Our core business is programming and research consultation, but we exist in the selling and marketing environment. Everybody does.

You don’t have to be a professional sales person to answer the question above. If you have human interaction of any kind, then you’ll “sell” something every day.

Ask the boss for a raise, and you’re selling the company on what you think you’re worth.

Ask for a date, and you’re selling the idea of togetherness, creating a need for companionship, with you as the solution to that need.

Ask a friend to do you a favor, and you’re selling the benefits of friendship and reciprocity.

The answer to “What is selling?” is “Everything is selling.”

Almost every environment exists because somebody with sales skills matched a need with a product or a service that fulfilled that need. Vehicles, cosmetics, hospitals, roller coasters you name it—a sales person created or sold a certain product that provided a solution to a specific problem.

In its typical definition, selling connotes economic exchange, not day-to-day human interaction. For sellers in electronic media, for example, the exchange is dollars for advertising time or message space.

“Selling is the mechanism that drives the economy,” said Charles Futrell, professor of marketing at Texas A & M University, to the Houston Chronicle.1 “It’s matching what you’re selling to a customer’s needs in a professional manner.” Futrell teaches selling at A & M’s Lowry Mays College and Graduate School of Business. The name of the school speaks volumes. Mays, founder and chairman of Clear Channel Communications, a media company that spans the globe, funded a business school, not a media school.

Mays talks about various forms of media as conduits from the advertiser to the viewer or listener. As sellers of advertising in electronic media, we’re sellers of the advertiser’s product. Mays explains: “We view ourselves as being in the business of selling automobiles, tamales, toothpaste, or whatever our customers want to move off their shelves. That culture, whether in radio or television, has served us well and keeps our focus where it should be, and that’s on the customer.”2

Zig Ziglar calls selling “a transference of feeling. If I (the salesman) can make you (the prospect) feel about my product the way I feel about my product, you are going to buy my product.” In Secrets of Closing the Sale,3 Ziglar added: “In order to transfer a feeling, you’ve got to have that feeling.” This is a very positive definition of selling, because it assumes that the seller is so enthusiastic about the product that the prospective buyer catches the euphoria.

There is a “process” to selling that guides behavior in a desired direction, culminating in the purchase. “The path to a sale is through uncovering client needs and satisfying those needs with product benefits,” say Charles Warner and Joseph Buchman in the classic textbook, Broadcast and Cable Selling.4 Warner and Buchman divided buyers into two groups—customers and prospects. “Customers” have already bought what you have to sell, and they need to be nurtured or resold. “Prospects” require information about your product, explanation of benefits, and evidence about expected results.

The last thing a prospect wants to be is “a prospect.” That makes him or her sound like a target, not a person. Sales trainer Tom Hopkins reminds us that not everyone wants to be sold. Negative perceptions about selling are a reality to millions of people. “It arises from the actions of the minority of salespeople who believe that selling is purely and simply aggression,” Hopkins writes in How to Master the Art of Selling.5

“Eventually all such vultures will be driven out of sales by the new breed of enlightened salespeople who qualify their prospects, care about their customers, and make sure their clients get benefit from their purchases that outweigh the prices paid.” In that statement, Hopkins gives us his definition of “sales.”

“Selling never changes,” says Mark McCormack, author of What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School. “There are no fads in selling, only basics,” he wrote.6 There are tools that become fads—cell phones, palmtop computers, a fax machine in the car, software to make your computer’s memory sharper, your client information more accessible, and your presentation more powerful. But tools don’t persuade the customer to commit. That’s the seller’s job.

Are You Selling or Are You Marketing?

Selling is trying to get someone to buy something. It’s the successful presentation of your product or service in such a way that your client sees the benefit of the purchase. The best salespeople make selling an art.

Marketing is also an art. Marketing means creating conditions by which the buyer is convinced to make a purchase without outside persuasion. Marketing involves developing a product or service that is perceived by customers to fit their needs so precisely that they want to buy it.

While this book has the word “selling” in its title, you’ll necessarily read a lot about marketing and its big-picture, long-term view of moving people toward making their own decisions. In relation, selling is the day-to-day, shorter-term concept of moving goods and services. You can see they’re dependent upon each other.

There is a difference between sales and marketing, and I’ve heard the differences expressed a hundred ways. Let’s start with just a few:

“Marketing is strategy; selling is tactics.”

“Selling is finding a need and filling it; marketing is finding a perceived need and filling it.”

“Selling is product-focused; marketing is customer-focused.”

“Marketing differs from sales in the sense that it involves creating a desire for the product that is related to emotion, image, or desire rather than practical need,” says Allen Shaw, President of Centennial Communications.

Gary Fries, President of the Radio Advertising Bureau, told me,7 “When I use the marketing approach, I save all the great reasons to advertise on my station and start right off focusing on the client. I spend my time asking clients about their industries, their specific businesses, their competitive advantages and disadvantages.”

The effective seller moves from marketing to selling and back again, often in the course of a few minutes. Depending on where you are in the sales process, you might find yourself either in a very customer-focused needs analysis (marketing) or asking for the order (selling). As quickly as you change hats, you must change back again.

In a 1990 study by the American Marketing Association, published as Marketing 2000 and Beyond, the change from selling to marketing was apparent:

As to perspectives, more members of the sales force will see themselves not as selling a product or commodity, such as plastic or telephones, but as total problem-solvers. They will be a part of a marketing team assisting customers in solving their problems efficiently and in generating satisfaction. They will be expected to bring additional services and capabilities to customers. They will help customers capitalize on their business or personal opportunities and to readily overcome hurdles and difficulties.8

There’s a complete outline of the sales process in Chapter 2. You’ll discover that product-focused presentations have a valuable place in the sales process, but that customer-focused selling makes the difference.

FIGURE 1-2 The lines between selling and marketing are blurred. To me, marketing is a circle that starts with the product, advertises to attract users, then measures feedback from those users to reshape the product. Then again, so is selling. There are two circles here, one for each of our targets: the advertiser and the end user—our viewers and listeners.

Television is new to the marketing aspect of selling. Sales people in TV often find that their clients have been treated as “targets,” not customers. That situation is a holdover from just a few years ago when TV had such a powerful lock on advertising dollars. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that TV caught up to the newspaper in the amount of advertising revenue it controlled. As an industry, television had not focused on customer needs as well as radio and cable both did.

That issue was reflected in a 1993 interview with Robert M. Ward, Director of Advertising Services for the Miller Brewing Company: “It is a real tribute to radio that it has delivered media value and promotion value long before it was perceived by many people as important. You’re now seeing the television industry, particularly the networks, with declining HUT [Households Using Television] levels, scrambling for business.”9

Today’s reality for television is an increase of media outlets competing for dollars and a concurrent decline in share. The whole concept of selling television changed to a customer focus out of necessity. “TV is still trying to figure it out,” says Diane Sutter, formerly Vice President of Shamrock Broadcasting, and later President and CEO of Shooting Star Broadcasting and owner of KTAB-TV in Abilene, Texas. “They’re learning problem-solving for the advertiser and value-added selling, like promotion ideas,” she told me.

In other words, marketing. Marketing starts, lives, and ends with your customer. “Marketing is making something happen,” says sales trainer Ken Greenwood. Sellers in the marketing environment “have to be comfortable in problem-solving.” He calls it “an opportunity-enabling environment” enabling your customer to take advantage of an opportunity to advertise on your medium.

You can see how the line between sales and marketing is very blurred. That’s good for us as sellers, because it’s good for our customers. When it comes to marketing, what you want is unimportant. It’s what your customer wants that matters. The customer is at the core of the definition of both marketing and sales.

Peter Drucker’s view is that “the customer is the business.” (My emphasis.) Drucker says in Managing for Results:10

1. What the people in the business think they know about customer and market is more likely to be wrong than right. There is only one person who really knows: the customer. Only by asking the customer, by watching him, by trying to understand his behavior can one find out who he is, what he does, how he buys, how he uses what he buys, what he expects, what he values, and so on.

2. The customer rarely buys what the business thinks it sells him. One reason for this is, of course, that nobody pays for a “product.” What is paid for is satisfactions. But nobody can make or supply satisfactions as such—at best, only the means to attaining them can be sold and delivered.

Drucker breaks down complex concepts into simple ideas: “A good deal of what is called ‘marketing’ today is at best organized, systematic selling.”

The most succinct definition of the word “sales” for sellers of electronic media comes from Diane Sutter:

Selling is identifying and satisfying customer needs profitably. Profitable for you, profitable for them.

That’s the definition I’ll use throughout this book because it reflects the customer-orientation of marketing as well as the product-orientation of selling.11 Sutter told me that this definition is a product of her training and her observation of the evolution of various selling styles. Sutter first heard a similar definition from Steve Marx, President of the Center for Sales Strategy, based in Tampa, Florida. Marx traces the idea to Don Beveridge who became a media sales trainer after years with Mobil Oil. Whatever the origin of the specific words, today’s selling is a win/win proposition: a win for the seller, and a win for the customer, too.

I once worked with a bright woman in the accounting department of a radio station who quit the radio business claiming she “couldn’t count barrels” in that job. Previously she worked at a paint warehouse. When she needed to know what was sold and what was not, she simply had someone conduct an inventory. In other words, she “counted barrels.”

Advertising time was very frustrating to her. There was nothing tangible for her to count when it came time to bill the clients. The announcers who read or played the commercials on the air made check marks on the station’s official log, yet nowhere was there an “inventory” from which to deduct the commercials. The idea of intangibility was foreign to an accountant who was trained to think only in concrete terms.

In electronic media, all we sell are intangibles: airtime, impressions, ratings points. Not even adding descriptive terms like “households,” “persons using television,” “cume audience,” or “hits” relieves the intangibility. None of these “products” is as easy to count as barrels. Intangible, however, should not be mistaken for unreal. In Selling Radio Direct, Michael Keith argues that broadcast time sellers “do not sell something immaterial. … Quite the reverse, airtime is very real and very concrete.” Without airtime for commercials, there would be no response to the advertising message.12

You’ve probably shopped at stores where the owner displays a newspaper or magazine ad in the store window or on a bulletin board. That’s the owner’s way of showing the tangible value received for an advertising dollar. “To the extent that a … commercial cannot be held or taped to a cash register, it is intangible,” writes Keith. “However, the results produced by a carefully conceived campaign can be seen in a cash register.”

Selling electronic media is different from retail sales or business-to-business selling. Our customer does not walk away from the selling transaction with something to wear, to eat, or to drive. Electronic media can only motivate the customer to purchase the wearable, the edible, or the driveable.

You can measure results from advertising in a variety of ways: the number of new customers, increased image for a product or service, or votes at the polling place. You can be assured also that your customer will measure results in a tangible way.

Fairfax Cone, of the Foote, Cone & Belding ad agency, said, “Advertising is what you do when you can’t go see somebody.” He said it in the time of the door-to-door salesperson, who presented brushes or cookware to women in their homes. The more difficult it became to knock on doors and make personal calls, the more important advertising became. Newspapers, magazines, radio, and TV then made the sales calls instead.

Electronic media as a whole is a powerful advertising tool because it commands the close attention of its users.

• Television and cable carry product demonstrations directly into the home and create demand. Video advertising offers compelling and memorable visual images that remain in the viewer’s memory. (That’s why video is so effective in building brands.)

• Radio creates a bond with its listeners because they can imagine so much about the personalities that they hear but don’t see. Radio’s ability to target by demographic group and lifestyle means that messages are perceived as direct communication, often in the vernacular of the listener.

• Interactive media and online services engage the consumer in a one-on-one exchange. If used properly, the messages can be specifically targeted to that one individual. Regular Internet surfers know the mesmerizing effect of linking from Web site to Web site, looking for one more piece of information, one more graphic. It’s a terrific environment for subject-specific advertising.

As a seller of traditional electronic media—TV, cable, radio—you’ll have a unique advantage: everybody knows what those forms of media do, how they work, and how they deliver an audience. People may not know your specific outlet, but they’ll have firsthand knowledge of the medium itself. Your job as a salesperson is to demonstrate the impact of your medium as an advertising vehicle.

WHAT’S IN A NAME

For the sake of simplicity, I use the terms “seller,” “salesperson,” and “salespeople” throughout this book. That’s about as generic as you can get. You’ll find, however, that no media organization uses those words or phrases on a business card.

Instead, some organizations use the term “Marketing Executive.” Others call their salespeople “Account Executives” or “Account Managers” because advertising agencies use those phrases for their client representatives.

The following sampling of real-world titles is designed to be illustrative, not comprehensive:

• NBC’s cable and international salespeople are “Account Executives.” So are sellers of E! Entertainment Television, CBS Television, CBS’s Eye On People, Lifetime, A & E, and The History Channel.

• Turner Sales employs “Sales Planners” to sell advertising on CNN, CNN-SI, Headline News, and The Airport Network. The same is true for Nickelodeon, Nick At Nite, and TV Land.

• Sellers of The Weather Channel and its sister network, The Travel Channel, are “Account Managers.”

• Kaleidoscope (the “Health, Wellness, and Ability” channel that began as a channel for the disabled) uses the phrase “Marketing Manager.”

• The CBS radio stations in Houston, Texas, employ “Account Managers,” and one seller is designated as the “Senior Account Manager.”

• I heard a commercial on our local classical music radio station looking for “Advertising Consultants.”

• The Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB) offers a study course for “Certified Radio Marketing Consultants.” Radio sales people who successfully complete the course use “CRMC” on their business cards like an academic degree.

One important fact to keep in mind as you embark on a career as a seller of electronic media: You can’t flatly sell anybody anything. You must help them discover that they need it.

I wonder how many people I’ve sat with in focus groups or in one-on-one research interviews. At some time during each project, the subject turns to advertising. Either I’m measuring the effectiveness of my client’s commercials or getting a sense of my client’s place in an increasingly cluttered advertising environment.

Despite the number and variety of ads we’re exposed to, no one admits to liking commercials. We’ve done research in markets as large as New York and Los Angeles and as small as West Point, Nebraska, and the response is the same: “Commercials don’t influence me.” Oh, but they do!

The enormous expenditure by advertisers to attract the attention of those consumers shows just how influential commercials really are. Approached without the face-value questions, most respondents in research projects will report brand awareness, product trial, and product affinity. But if told that their product choices are due to advertising, they’ll argue. Immunity to advertising is one of humankind’s most comforting self-delusions.

“Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, and the trouble is I don’t know which half,” said Lord Leverhulme (later quoted by department store magnate John Wanamaker, who now gets the credit for the phrase).13 Each man would have been comforted by today’s media measurement. They would have seen the cause and effect relationship between advertising and purchase levels.

Advertising is impossible to separate from the economy as a whole, especially the uniquely American economy of abundance. In an economy based on scarcity, total demand is usually equal to or in excess of total supply. Thus every producer sells everything that’s produced. When supply outstrips demand—as in the U.S. economic system, for example—advertising fulfills an essential function: moving merchandise from the manufacturer to consumer.

In a 1953 lecture at the University of Chicago,14 Yale University’s David M. Potter explained his views on the role of advertising:

In a society of abundance, the productive capacity can supply new kinds of goods faster than society in the mass learns to crave these goods or to regard them as necessities. If this new capacity is to be used, the imperative must fall upon consumption, and the society must be adjusted to a new set of drives and values in which consumption is paramount. … Clearly it must be educated, and the only institution we have for instilling new needs, for training people to act as consumers, for altering men’s values and thus for hastening their adjustment to potential abundance, is advertising.

Advertising existed long before the United States did, yet the United States took an early and commanding lead in using advertising to fuel the nation’s economic growth. Popular forms of media have a rich history of subsidy by advertisers who want access to consumers who use that media. An NBC-TV executive expressed it this way: “We deliver eyeballs to advertisers.”

If focus on the customer is the basis for sales in electronic media, then Clear Channel’s Lowry Mays answered the question “What business are we in?” earlier: “In the customer’s business.” Yet, as we discussed earlier, it’s impossible not to say that you’re in television or cable or interactive sales, isn’t it?

That brings to mind the famous Harvard Business Review article by Theodore Levitt, who taught us that the railroads didn’t stop growing because passengers didn’t want to travel.15 The railroads let other means of transportation take their customers away. Railroads perceived themselves to be in the railroad business, not the transportation business.

Some other examples:

• Charles Revson’s company sells cosmetics, but Revson claims that he sells “hope” to buyers of his Revlon products.

• A hardware representative once said that his product was quarter-inch drill bits, but all his customers ever wanted were quarter-inch holes.

The core business of electronic media, then, is helping clients achieve their sales and marketing goals. We’re in the advertising business, but we should be selling “hope” and “holes.”

“Advertising is communication—mass produced, a brain child of our mechanized civilization.” That statement is from a 1953 article in the trade publication Printer’s Ink.16 It continued in grandiose prose to rhapsodize about new discoveries that contributed to the “betterment of health and home” and about new methods of distribution of goods. The report stated the case for advertising in a defensive tone. I don’t know if there had been a specific attack that prompted it or if the journal was answering criticism that has surrounded advertising from the beginning.

Calling advertising “the most economical way of bridging the gap between the man with an idea and the man who can benefit by buying it,” Printer’s Ink listed twenty-four “basic accomplishments of advertising.” Here are a few of them:

• Advertising makes possible better merchandise at lower prices.

• Advertising helps cut the cost of distribution.

• Advertising pre-sells known brands.

• Advertising creates markets.

• Advertising speeds the introduction of new products.

• Advertising reaches prospects who won’t see a salesman.

• Advertising establishes friendly relations with the public.

• Advertising helps stabilize a business.

• Advertising smokes out new prospects.

• Advertising foots the bill.

The last item, of course, makes the case for advertising in electronic media: Advertising pays the bills, allowing a constant flow of entertainment and information. Every time you sell a minute of airtime, a sponsorship of a Web page, a concert event for TV, or a scrolling announcement on a local cable channel, you’re fueling the economy. In 1973, Variety reported that by a margin of 5–1, Americans judged television commercials as “a fair price to pay for being able to view the programs.”17

There are three beneficiaries of the advertising you sell:

1. Consumers. Advertising is a terrific information source, saving time and trouble in shopping, comparing brands, and testing results. Brand advertising especially has given the consumer standards for measuring product against product.

2. Business. Advertising cuts selling costs and saves time for sales representatives.

3. The economy. Advertising sells products, which keeps distribution moving, which stimulates the supply of goods, which keeps workers at their jobs, which provides spending power to respond to advertising.18

The earliest advertisements in English are still with us. They’re not radio or TV commercials; they’re not banners on Web pages. They are people. People named Smith and Goldsmith. People named Wright, Miller, Weaver, and Baker. Their surnames are the occupations of long gone ancestors.19 Before the rise of England’s domestic trade, people were known by their ancestry (“Tom, Dick’s son” became known as “Tom Dickson”). Other names were derived from where people lived (“John at the wood” became “John Atwood”).

With the increase of trade came the need for identification with the products or services each person could provide. Skills passed from parent to progeny, and so did names. Trade and advertising were born together, and they’ve remained together.

Well-known historical figures from the colonial period of the United States believed in advertising. George Washington distributed “trade cards” that offered his services as a surveyor. Paul Revere did the same for his silversmith business. Trade cards were oversized business cards that were lavishly illustrated. Professional men and tradesmen handed them to the public to drum up business.

As commerce progressed, advertising expanded to signage. A pub called “The Angel and Harp” created a sign that offered its name using both words and pictures. Customers who could not read knew that seeing a representation of an angel and a harp indicated a place to stop for a pint of ale or a night of rest.

Signage became the principal medium for advertising during the founding years of the United States. “Bill posters” would spread their signs against fences and anchor them with a glue-like whitewash applied with a large broom or brush.

Still considered classics of American advertising are the hyperbolic posters for P. T. Barnum’s American Museum. There he displayed oddities like the midget General Tom Thumb, extravagant “Wild West Shows,” and true talents like the soprano Jenny Lind. Barnum was an imaginative showman, and his contribution to advertising cannot be denied. It was Barnum who said, “If a man has not the pluck to keep on advertising, all the money he has already spent is lost.”

Surprisingly, when newspapers became popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, advertising was considered less than respectable. Termed “puffing,” advertising was thought to be the province of patent medicines, elixirs whose pitchmen wove tales of curative powers. There was even a feeling among newspaper and magazine publishers that advertising violated the integrity of their journals. Not even the potential for revenue could temper prejudice against advertising. Merchants themselves needed persuasion not only that advertising was worth spending money on, but also that such open and brazen hawking of wares was not disreputable. Those who chose to advertise fought an uphill battle against publishers who felt that advertising was a sign of commercial distress, the last step before bankruptcy.

Harper’s magazine took such a negative attitude towards advertising that it once rejected $18,000.00 (an enormous sum in the 1800s) for a series of ads from a sewing machine manufacturer. Harper’s chose instead to advertise its own books on that page.

In 1841, a Philadelphian named Volney B. Palmer founded what appears to be the first advertising agency.20 The field was looked upon with such disdain that Palmer was forced to sell real estate, coal, and firewood to make a living. Palmer described himself as a “newspaper agent” rather than an advertising agent. He made it clear to advertisers that he worked for the publishers, not for them. The advantages of his services were savings of cost and time in trying to contact a variety of publishers. One-stop shopping.

Also in the 1840s, a New Yorker named John L. Hooper was soliciting advertising for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Often, when Hooper sold an ad in the Tribune, his customers asked him to place the same ad in other papers. Hooper was pleased to oblige, but Greeley frowned on the idea of giving away revenues that he thought should be funneled into the Tribune. So, Hooper resigned and became an advertising agent.

Although Palmer and Hooper were pioneers, today’s major ad agencies trace their heritage not to them but to a Boston company founded by George P. Rowell. Rowell gave up his job as an advertising solicitor for the Boston Post in 1865 to begin an organized approach to the disarray of newspaper advertising. At the time, newspaper circulation figures were largely unverifiable, rate cards showed what the publishers hoped to get for their ads rather than the value of the space, and commissions could vary from zero to as much as 75% of the rate. Rowell sensed opportunity.

Another of advertising’s early success stories is an Englishman named Thomas J. Bar-ratt, who in 1865 became a partner in the small firm that manufactured Pear’s Soap. At the time, Pear’s spent about £80 a year on advertising. Within a decade, Barratt had increased that amount to more than £100,000 a year.

The message was simple: “Pear’s Soap.” No slogans, no explanations, no benefits, no features. Just repetition of the name in newspapers, magazines, posters, and billboards. Barratt’s intention was a conditioned response: the idea of “soap” conjured the brand name “Pear’s.”

It worked. Pear’s became the most widely known commercial product in the world. Later, Pear’s added slogans, as did all advertisers in the future.

Early slogans were simple: “The Best,” “Guaranteed Invaluable,” and “Pleasant to the “urste.” They seem primitive by today’s standards, yet they were useful mnemonic devices that helped the public remember the product.

The word “slogan” comes from the Gaelic sluagh-ghairm, a battle cry. The word that once stood for the fierce yells of warriors carving each other with claymores now stands for “a phrase used in order that the prospect may become favorably disposed toward the article for sale.”

By the 1880s, there was a widespread fondness for slogans. It developed to the extent that slogans were the only message communicated in advertisements. Using slogans was an advertising milestone. They added power to the message, but they also added power to the craft. In fact, for the first time, advertising was acknowledged as a craft. It had grown from simple announcements to true sophistication.21

His solution was a package service: he calculated realistic estimates of newspaper circulation and then guaranteed the publishers cash payments. Each idea was a surprise—the former a rude deflation of circulation figures, the latter a welcome relief to papers that struggled for collections. Rowell bought newspaper space at what we would call “wholesale” rates and resold it to advertisers at retail. Publishers were enthusiastic because they were guaranteed payment and because Rowell assumed the risk. In small towns and rural areas, subscription fees had often been paid in eggs, vegetables, or hay, so cash for advertising was very attractive.

Every new idea Rowell had was considered an innovation:

• He became a space wholesaler for small newspapers.

• He began a flat 25% commission structure.

• He announced a policy of working only for the advertiser, not for the newspaper.

• He collected all his data about circulation figures and made it public in Rowell’s American Newspaper Directory, which first appeared in 1869.

• He founded Printer’s Ink, a crusading trade magazine for the advertising industry that lasted well into the twentieth century.22

Those who came after George Rowell began in earnest to shape American advertising. N. W. Ayer’s agency, founded in 1869, grew large enough to buy Rowell’s agency in the 1890s. Another agency established in the 1860s, Carlton and Smith, was bought in 1867 and renamed by James Walter Thompson. In order to secure a line of credit, Thompson claimed to have been a commodore and hero in the Union Navy during the Civil War. The story was as hyperbolic as the advertising Thompson would write, but it was based in truth: Thompson’s assignment during the war was shoveling coal on a Union steamship.

The advertising agency came into existence because both publishers and advertisers needed help to sort rates, write effective copy, and make deals. In Advertising in America, editor Poyntz Tyler gives this perspective on the development of the ad agency: “In a larger sense, the agency’s chief service in this early period was to promote the general use of advertising, and thus to aid in discovering cheaper and more effective ways of marketing goods.”

The admen who brought the industry into the twentieth century are described by David Ogilvy as the “six giants who invented modern advertising”:23

Albert Lasker (1880–1952). First an employee, later the owner of 95% of Lord and Thomas in Chicago. The agency became “Foote, Cone, & Belding” when three top employees renamed it a month after Lasker retired.

Stanley Resor (1879–1962). When he became head of J. Walter Thompson, the agency billed $3,000,000. When he retired 45 years later, it was the biggest agency in the world, with billings of $500,000,000.

Raymond Rubicam (1892–1978). He and a co-worker resigned from the N. W. Ayer agency in 1923 to form Young & Rubicam in 1923. Ogilvy claims Young & Rubicam ads have been read by more people than any other agency’s ads.

Leo Burnett (1891–1971). Feeling that Chicago was more “real” a town than “mythical” New York, Burnett established the Chicago school of advertising to “talk turkey” to the majority of Americans. By the time of his death, his agency was the biggest in the world outside of that mythical town. His legacy is a list of all-American icons: Tony the Tiger, the Jolly Green Giant, and the Pillsbury Doughboy.

Claude C. Hopkins (1867–1932). From his typewriter at Lord & Thomas, he made many products famous, including Pepsodent toothpaste, Palmolive soaps, and six different automobiles. He invented sampling by coupon and developed copy research.

Bill Bernbach (1911–1982). Known as “the Picasso of Madison Avenue,” his goal was to raise advertising to an art. Bernbach achieved that goal with television commercials that showed monkeys manhandling American Tourister luggage, Volkswagen ads advising “Think Small,” and the classic confession from Avis Rent-a-Car: “We’re #2. We Try Harder.” (Bold added for emphasis.)

David Ogilvy assembled that list, but did not include his own name. Ogilvy was also one of the giants. In The Image Makers by William Meyers, he’s been described as “a dotty Englishman” who flunked Oxford, sold ovens door to door in Scotland, apprenticed as a chef in Paris, then wandered to America for a wartime post with the British government. He opened a U.S. branch of an English ad agency, then bought the firm and renamed it Ogilvy and Mather.

Treating Ogilvy’s story here with just a paragraph or two is counter to the Ogilvy philosophy. He was a fanatic for long text. The more he told, the more he sold, he said. Testament to that philosophy are dense, copy-laden print ads that explained products in minute detail. A mid-1950’s layout for Rolls Royce automobiles contained 719 words with a 19-word headline!

He wrote in Ogilvy on Advertising: “When I write an advertisement, I don’t want you to tell me that you find it ‘creative.’ I want you to find it so interesting that you buy the product.”

Advertising, of course, sells more than just the product. It also sells image—the combined total of the impressions, promises, perceptions, and experiences with a product or service. All those factors weave information about a brand into the consumer’s mental storehouse. There are so many factors that contribute to brand image, including what happens when a consumer opens a package or calls a toll-free customer service number.24

The Association of National Advertisers (ANA) separates “brand image” from “brand identity.” Brand identity is a specific combination of visual and verbal elements that help to achieve recognition of the brand and differentiation from other brands. The components ofbrand identity, according to the ANA, are:

• The name of the brand

• Logos, such as the Nike swoosh symbol or the Coca-Cola lettering

• Symbols, such as Mickey Mouse or Ronald McDonald

• Slogans and messages

• Color, such as the IBM blue

• Package configuration, such as the Campbell’s red and white soup can label

• Product configuration, such as the original Coca-Cola bottle

“Of all the things that companies own, brands are far and away the most important and the toughest,” said Jim Mullen, whose agency produced brand advertising for BMW, Colgate, and Hewlett-Packard, among others. “Founders die. Factories burn down. Machinery wears out. Inventories get depleted. Technology becomes obsolete. Of your three forms of intellectual property—brands, patents, and copyrights—only one can never expire.”

Mullen told Reputation Management magazine that his favorite brand is Morton’s Salt:

Morton’s Salt has a huge share of the American market, as much as 50% of all salt sold. Moreover, Morton’s Salt costs about a nickel more per box than other salt.

In order to understand the dynamics of its brand, Morton’s has conducted a fair amount of research. In focus groups, chemists have explained to consumers that salt is the lowest technology product in the world. Salt is salt: one molecule of sodium combined with another of chlorine to make sodium chloride. There is no such thing as premium salt, no designer salt, no salt seconds, just salt.

When this was explained to consumers and then they were asked how many would still buy Morton’s, half remained loyal to the brand.

FIGURE 1-3 They say pictures of animals sell books, but these are here to reinforce branding. Animal Planet is an extension of the Discovery Channel, another well-branded network. Consistent with the Animal Planet theme, the ad slick they sent me was printed on recycled paper. Courtesy Animal Planet. Used with permission.

The focus groups were pushed further. Not only is salt salt, the moderator told them, but Morton actually co-packs about a third of the salt sold under other brand names. When the consumers were queried again about their purchase intentions, the same 50% indicated a preference for Morton’s.

Why? Because these people aren’t buying salt, they’re buying trust.25

Branding is as old as the signage on the pub I described earlier or the silversmith’s stamp on the back of an ancient goblet. The message in the stamp was that the consumer could rely on the product. Advertising carries as much of the brand message today as the product itself does, and brands are reinforced by their exposure in our commercials.

In American advertising, a brand is considered a business asset. Financial analysts measure pricing of brand name items against the average price of unbranded competitors, and then they multiply by the number of units sold. The result is the billion dollar valuation of brands from products such as vodka, cereal, or chewing gum. For example, Wrigley’s Spearmint is one of the most famous brands in America. It has survived virtually unchanged since 1893.

How many other brands have lasted for decades? Quite a few: Campbell’s, Coca-Cola, Del Monte, General Electric, Gillette, Goodyear, Kodak, Ivory, and Nabisco. The Advertiser, a publication of the ANA, noted that these brands, including Wrigley’s, were number one in their fields in 1923 and remained number one well into the 1990s.

The dictionary defines “brand” as “to mark indelibly as proof of ownership.” It also means “a sign of quality.” Marketer Larry Light, who chairs the Coalition for Brand Equity, adds to the definition: “A brand is a trademark that differentiates a promise associated with a product and identifies the source of that promise.”26

CBS was the first major broadcaster to brand itself, both on the air and in its corporate communications. Lou Dorfsman, the former CBS Vice President and Creative Director imposed the “CBS eye” logo on everything. A typeface that Dorfsman developed (“CBS Didot”) was applied to everything from ads for network TV shows to the type on menus in the CBS dining rooms. Dorfsman even won a fight with the New York City Fire Department over the design of “exit” signs in the CBS building.

Branding for CBS was “unity of design” under Dorfsman’s watchful eye. “Watchful” is an understatement: The ANA called Dorfsman the “image czar” because of his vigilance of the CBS brand icons. (If you enjoy graphic arts, please see the beautiful book, Dorfsman & CBS by Dick Hess and Marion Muller, a retrospective of Dorfsman’s terrific work.)27

Branding in those days (the 1950s through the 1980s) did not apply specifically to the programming on any TV network. The network schedules were comprised of a broad variety of shows, known as “horizontal programming.” A sitcom would be followed by a music special, then a news program, then a documentary. There was no overall theme to the shows. (In the era of CBS founder William Paley—that network maintained a level of such high quality programming that CBS was called the “Tiffany network.”)

FIGURE 1-4 This benign frog face is a radio station brand in more than twenty markets. Sinclair Communications’ chairman Kerby Confer originated the K-FROG, BIG FROG, and FROGGY concept. Branding is supported on the air with disc jockey names like “Hopalong Cassidy,” “Ann Phibian,” and “I. B. Green.” This particular logo is from KFRG, San Bernardino, California, and is used with permission.

FIGURE 1-5 The CBS “look” continues as the “eye” logo is applied to CBS cable ventures. TNN (The Nashville Network) and CMT (Country Music Television) are the remaining CBS cable channels in the United States. This ad was created when CBS also owned a controlling interest in the TeleNoticias news network that serves Latin America. Courtesy CBS cable. Used with permission.

Advertising and Electronic Media

Electronic media is traced to the 1830s when Samuel Morse tapped out dots and dashes over telegraph wires. His first “Morse code” message traveled 200 feet. His work opened communications over long distances and tied the growing United States together. In 1875, Alexander Graham Bell accidentally stumbled across the secret of transmitting voice over the same type of wires, giving birth to the telephone.

The man credited as the “father of radio” is Guglielmo Marconi, who transmitted across the Atlantic in 1901. His message—the letter “S” in Morse Code—was sent from a base station in Wales to St. John’s, Newfoundland.28 In its earliest days, radio was used primarily by the military for ship-to-shore communications.

Radio’s early literature is full of tales of experimentation, some of it commercially motivated. In 1910, John Wanamaker installed a transmitter in his Philadelphia department store and broadcast a radio show. The first “advertiser” on radio was a record retailer in Wilkinsburgh, Pennsylvania, who provided discs for Dr. Frank Conrad, the Westinghouse engineer who had been experimenting with station 8XK. Dr. Conrad broadcast music supplied by the store during the summer of 1920. By September, the Joseph Horne Company, a Pittsburgh department store, was advertising in the newspaper that receivers for Dr. Conrad’s programs could be purchased at their store.29

Because of the positive response, Westinghouse officials became so confident of the new idea that they quickly authorized a license application and broadcast that fall’s presidential election returns on their newly christened KDKA.

The next year Westinghouse produced the first popular-price home receiver (about $60, not including headsets or speakers) and established radio stations in cities where it had manufacturing plants—East Springfield, MA; Newark, NJ; and Chicago, IL. The stations were broadcasting not to sell advertising, but to sell radio sets.

General Electric, AT & T, and RCA quickly followed suit, selling their own radio sets on their own stations. David Sarnoff, founder of RCA, used the airwaves to sell what he called a “radio music box.” In 1922, sales reached $11,000,000. The next year they more than doubled, reaching $22,500,000. By the third year sales were at $50,000,000.

Audience growth was just as steady. The power of the new medium was felt immediately. Radio was blamed for a 30% decline in magazine subscriptions and for a 90% drop in record sales. By the end of 1922, there were more than 200 radio stations broadcasting to over 3,000,000 radio homes. In 1923, radio licenses totalled 600, but no one had determined just how the stations could support themselves.

AT & T’s New York station, WEAF, inaugurated a policy of continuous broadcasting with a rate card based on time: ten minutes for $100. In one of the first sponsored programs, 5:15 p.m. on August 28, 1922, there was a discussion of the advantages of apartments developed by the Queensborough Corporation in Jackson Heights, New York. The Radio Advertising Bureau identifies the copy writers as Robert and Albert McDougal, and the sales person as George Blackwell.

WEAF’s breakthrough did not cause advertisers to flock to radio. Newspapers, billboards, and handbills remained the favored media. Secretary of Commerce (later President) Herbert Hoover didn’t help matters when he predicted “the American people will never stand still for advertising on American radio.” Fortunately for electronic media, he was wrong. By the late 1920s, radio became as inexorably linked to the concept of advertising as newspapers had been.30

A cigar commercial was the origin of the CBS we know today. There were several attempts at creating a network to compete with the fledgling, but successful, National Broadcasting Company (NBC). The competition NBC liked best was its own combination of Red and Blue Networks, designed to give variety to broadcasting but keep the profits in house.

In 1927, United Independent Broadcasters took a run at NBC, but soon ran out of money. To get an infusion of cash, United sold operating rights to Columbia Phonograph Company, which changed the network’s name to “Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System,” hoping to increase publicity for its recordings. Within weeks, Columbia discovered the mistake of its investment and sold the rights back to United.

In stepped William Paley, the 27-year-old son of a Philadelphia cigar maker. Business at Congress Cigar Co. had dropped off because of the rising popularity of cigarettes, and Paley began to advertise “La Palina” cigars on WCAU, the local Philadelphia station. Sales jumped from fewer than 400,000 cigars a day to over a million.

Feeling that radio “was an astounding business,” Paley bought a controlling interest in the new network to peddle daddy’s cigars. Within two years, he turned a profit with CBS and was in radio for the long run.31

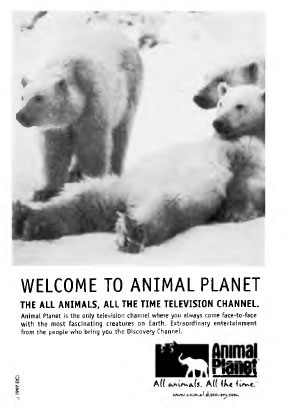

Radio became the advertiser’s dream as it linked the nation in the 1930s with variety shows, orchestras, comedians, and daily dramas that reflected real-life stories. Those dramas became known as “soap operas,” because of the advertising aimed at women who were not in the work force at the time.

Prominent companies begin to reallocate substantial portions of their print advertising budgets for radio because radio advertising worked. Expenditures on radio increased from $20 million in 1928 to $165 million in 1937. The numbers are scant by today’s standards, but remarkable considering the nation was weathering the Great Depression. A McGraw-Hill book called Radio As An Advertising Medium reported that all of radio’s (network) advertisers in 1936 repeated their buys in 1937. “These former doubters discovered that radio was a very concrete way to market their products,” says Michael Keith in Selling Radio Direct.33

As new stations took the air, their call signs reflected the names or slogans of other companies who used radio for commercial ends:32

WEEI, Boston-Edison Electrical Institute

WGL, Fort Wayne-”World’s Greatest Loudspeaker” (Magnavox)

WOW, Omaha—Woodmen of the World (Insurance)

WGN, Chicago—”World’s Greatest Newspaper” (The Chicago Tribune)

WMT, Waterloo, Iowa—Waterloo Morning Tribune

WBRE, Wilkes-Barre—Baltimore Radio Exchange

KRLD, Dallas—Radio Labs of Dallas

WLS, Chicago-”World’s Largest Store” (Sears)

WLAC, Nashville—Life and Casualty (Insurance)

Advertising as we know it today is steeped in our images of television. The turning point is marked in 1954 when a group of Ted Bates & Company executives met at a Manhattan restaurant to discuss a headache remedy. Rosser Reeves, head of Bates at the time, drew the outline of a man’s skull on one of the restaurant’s linen napkins. Inside the skull were three boxes. One contained a crackling lightning bolt, another a creaky spring, the third a pounding hammer. In his mind’s ear, Reeves heard a cacophony of lightning bolts, coiled springs, and hammering sounds ending with an announcer saying:

“Anacin—for fast, fast, fast relief!”

The doodles were animated on film as the first “real” television commercial. Before that time, ads on television were largely product demonstrations performed live on camera.

William Meyers writes of Reeves in The Image Makers: “With his ability to harness the immense power of television, Rosser Reeves transformed advertising almost overnight from low-keyed salesmanship into high-powered persuasion. Known along Madison Avenue as ‘the blacksmith,’ he believed that commercials should be mind-pulverizing. To be effective, they had to bludgeon people into buying.”34

Within seven years, Reeves’ Anacin commercial had made more money for American Home Products than Gone With the Wind had grossed for MGM studios in a quarter of a century. He developed aggressive campaigns for M & M’s candies, Viceroy and Kool cigarettes, and Minute Maid orange juice, among others.

Reeves is also credited for the first TV advertising for a presidential candidate. His ads for the 1952 Eisenhower campaign were attacked as “Machiavellian” because they sold the candidate like toothpaste. This concept is so commonplace now that it’s hard to believe there was ever such an outcry.

Television changed the way advertising agencies did their work. In the heyday of radio, agencies produced programs and paid for the network time to air them. Because of the shortage of prime time hours on network TV, NBC and CBS retained full control of their programming in TV’s formative years. (ABC-TV followed suit, but long after NBC and CBS television networks were established.)

FIGURE 1-6 A ventriloquist’s dummy in a top hat and tails dominated Sunday nights in America during the late 1930s. This graphic, based on C. E. Hooper radio reports showed more than 80% of the nation’s ears were tuned to “The Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show.”

A 1956 issue of Fortune magazine called television “a fearful headache” for agencies:

Ideally, they would like to be in on the production of more shows; they would like to have something to say about which shows get on the air; they would like some firm assurances that shows would be allowed to stay on the air so long as the sponsor was happy with them. They would like, in short, to have as much influence in TV as they did in radio during the great days of that medium in the 1930s.35

As it turned out, those early fears were unwarranted because ad agencies quickly learned to work within the structure of the new medium. Rosser Reeves’ commercial for Anacin proved that TV was not a headache at all. Television provided a remarkable canvas for advertising’s creative people. The power of the medium made commercials extremely effective.

It’s surprising to discover that on the earliest TV broadcasts commercials were banned by law. According to rulings issued by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1936, a television station was for “research and experimentation.” They could make an announcement of a sponsor and show the product or the logo, but that was all.

TV broadcasters were not allowed to solicit commercials or to charge additional rates for sponsorships that were re-transmitted (for example on a network). “The generous advertising dollars that have built broadcasting to its present greatness are closed to television at the present writing,” lamented Radio As An Advertising Medium in 1939.

The radio networks at the time felt television was no threat to them. Lenox Lohr, President of NBC, said “You can’t watch television while you are eating, dressing, playing bridge, or doing odd jobs around the house.” Founder William Paley of CBS, echoed the sentiment: “It will not, I believe, undermine or replace present broadcasting.”

Lohr’s remarks seem ludicrous today as television permeates so many of life’s activities. Strictly speaking, Paley’s remarks were more prophetic, because new media do not displace previous media, they only add to the media mix.

After a hiatus for World War II, television as a commercial entity made a hearty run at radio in the early 1950s, and won the battle for the eye, the mind, and the leisure time of the American people. Since then, radio has been unable to regain the share of national advertising dollars it attracted before the arrival of TV.

Today’s Television Environment

In the wake of Hurricane Andrew, which devastated southern Florida in 1992, Sears stores used radio to advertise television antennas as part of the “clean up” after the storm. A Sears executive explained the campaign saying, “Television is so much a part of life that people probably think about it before they get their roof back on.”36

That’s a provocative statement about a pervasive medium. There’s no question that American television is a dominant cultural force. As Neil Postman put it, “There is no audience so young that it is barred from television. There is no poverty so abject that it must forgo television. There is no education so exalted that it is not modified by television.”37

Postman (and so many others) warn us about “amusing ourselves to death” by letting modern media trivialize life, culture, and information. As early as the mid-1970s, there were books and articles arguing for the elimination of television. In the 1960s, FCC commissioner Newton Minnow called the television medium “a vast wasteland.”

Media critic Sut Jhally calls television “the dream life of our culture” in a documentary called “The Ad and the Ego.” In the same video, critic Jean Kilbourne complains that television ads “tell us who we are and who we should be.”

Personally, I like the approach taken by Tony Schwartz. He’s not afraid to call electronic media “the second God” in an analogy of how media influences our lives and shapes our beliefs. “Media are all knowing,” he writes. “They supply a community of knowledge and feelings, and a common morality.”38

The reason I like Schwartz is that he makes his living by shaping advertising that effectively uses electronic media. Unlike the critics who complain and offer no solutions, Schwartz feels we all have a responsibility “to use the second god as a social instrument in the hands of society.”

Schwartz understands that the most effective commercials “do not tell us what to do or how to react. They present carefully chosen stimuli that evoke certain inner connections and elicit the desired behavior or reaction.” Using AT & T commercials as examples, Schwartz says, “The spots did not direct people to make long distance calls. They made them feel like doing so.” He also admits that some commercials “offend us by shouting at us and trying to pressure us into buying.”

Despite its proponents, every new medium experiences its share of criticism. In one of the earliest media criticisms, Socrates told the story of King Thamus evaluating the “inventions” of the god Theuth: numbers, calculation, astronomy, and writing. Thamus warns that those who take up writing will “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful,” using “external signs” instead of their own internal resources.39

For another example, Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press was hailed as a new medium that distributed printed words around the globe. Simultaneously, it was decried for giving each person the power to interpret words without help, thus undermining the authority of both church and state.

Even though advertising has its critics, there is little doubt that it has helped to shape our economy. Television advertising shapes our culture and our world view; it has expanded from largely descriptive product demonstrations on the first flickering black and white screens to the Anacin-type “made for TV” commercials to today’s impressionistic and evocative imagery. Tony Schwartz calls the language of video imagery “the new grammar.”

Neil Postman complains that “the television commercial is not at all about the character of products to be consumed. It is about the character of the consumers of products. Images of movie stars and famous athletes, of serene lakes and macho fishing trips, of elegant dinners and romantic interludes, of happy families packing their station wagons for a picnic in the country—these tell nothing about the products being sold. But they tell everything about the fears, fancies and dreams of those who might buy them.”

Another common complaint about commercials in electronic media is that we are unable to avoid them easily. In the newspaper, we can turn the page or divert our attention to another article or another ad. In radio, TV, and cable, commercials are intrusive. Unless we lower the volume, turn off the set, or zip and zap with the remote button, we cannot skip the commercials. Online advertising borrows from TV with interstitial ads that pop up at the end of interactive segments. These ads, too, are virtually impossible to avoid.

FIGURE 1-7 The network that claims to be “34% Better Than Real Life,” complete with classic TV shows and vintage commercials. “Here in TV Land, we call ‘em ‘retromercials,’” says the TV Land presentation kit. Used with permission. MTV Networks.

TABLE 1–1 U.S. Advertising Volume

All things considered, the TV networks did well in 1997, especially given basic cable’s increased audience. Cable received the benefits—high double digit increases in advertising revenues.

These figures are the most-anticipated numbers of any year. Robert J. Coen, Senior Vice President, Forecasting for McCann-Erickson Worldwide is advertising’s official scorekeeper.

The McCann-Erickson U.S. advertising volume reports represent all expenditures by U.S. advertisers—national, local, private individuals, etc. The expenditures, by medium, include all commissions as well as the art, mechanical, and production expenses that are part of the advertising budget for each medium.

Source: Robert J. Coen, McCann-Erickson Worldwide. Prepared for Advertising Age, May 18, 1998.

However, some people don’t want to skip commercials. Nick at Nite’s TV Land, for example, promises to “put a sparkle back into television” by running 24 hours of classic TV shows every day. TV Land also runs classic commercials. They call them “retromercials,” interrupting original programs like “The Sonny and Cher Show” or “The Ed Sullivan Show” with the Oscar Mayer song or a squeeze of the Charmin roll by Mr. Whipple.

Tony Schwartz says, “A commercial can have extraordinary power when it makes people conclude that it is putting them in touch with a piece of reality.” TV Land takes that idea one step further in a mocking way by claiming that their classic programming and commercials are “34% better than real life.”

A seller of television, cable, and interactive media must bear in mind that forms of visual media have created their own context. In many cases, the framework of a television program is television itself. That means that the commercial you sell fits into three contexts:

• The need or desire on the part of the consumer

• The context of advertising

• The context of television

Sociologists and critics will add more, I’m sure, but that’s not my task in this book. There’s no question of the impact of television and visual media. That’s why they’re so desirable for distributing advertising messages.

Advertising has shown itself to be virtually recession-proof. It has consistently outpaced inflation in its percentage of growth year to year. Some of that growth is a result of the growth of individual media. From 1985 to 1990, for example, the explosive rate of television advertising revenues were roughly equal to overall advertising increases.

Mass products can reach mass audiences quickly with broadcast television, while targeted media—radio, cable, magazines, and interactive media—reinforce the message to specific audiences.

Repeating something that we discussed earlier: Advertising creates markets. As you’ll see in the next section, there are a lot of venues for advertising in electronic media.

The Electronic Media Environment

You should have seen my office during the preparation for this book! It was the metaphor for the explosion of media options available to consumers. My floor was littered with media kits from national cable networks, TV syndicators, regional news and sports channels, radio stations, TV stations, and TV and radio networks. Some were extremely elaborate:

• The media kit for Nick At Nite had a navy blue cover with flocked faux velvet, stamped with gold caricatures of old-time TV favorites and Nick at Nite’s slogan, “Classic TV You Can Trust.”

• Nickelodeon’s main network sold itself with a green plastic pouch (the color of Nick’s slimy “Gak”) with what looks like kids’ artwork showing through.

• A translucent notebook held E! Entertainment Television’s audience research data, showing how an advertiser can mix and match programming to develop theme-based or demographic-based campaigns.

• CNN combined all their services—CNN, The Headline News Network, CNN-fn, CNN-Interactive, and the Airport Channel—in one presentation “pouch,” a bright red cardboard envelope.

• Westwood One radio networks sent a 64-page, magazine-style catalog of all their programs: from CBS, NBC, and Mutual News and Shadow Traffic reports to talk shows like G. Gordon Liddy and “Imus in the Morning” to weekend music specials.

• Superstation WGN introduces the parent company and all its holdings (newspapers, TV and radio stations, The Farm Journal magazine, and the Chicago Cubs baseball team), then outlines programming, target demographics, and national reach.

• American Movie Classics (AMC) has an oversized folio with classic movie posters on the front and stills from classic films inside.

• The Houston Astros present prospective advertisers with a pocket-sized kit with details about the Astros Radio Network and signage in the ball park.

Presentations by local radio stations ranged from reams of statistics about audience reach to photographs of live broadcasts with disc jockeys, mascots, and wheels of fortune that listeners spin to win prizes. One small town station spent more time on its broadcast power than on whether anyone took advantage of that power to actually listen.

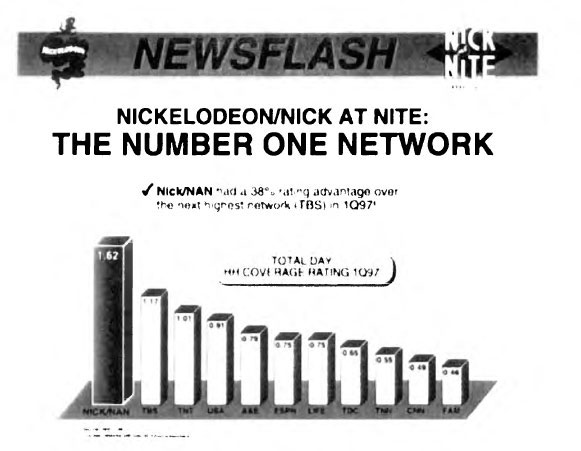

FIGURE 1-8 Too bad you can’t get the sense of fun from the Nickelodeon presentation kit in a green plastic pouch that says “kids” (without having to read the graphics that actually say “Superkids”). Here’s Nickelodeon in black and white, showing their household rating. Used with permission. MTV Networks.

Next to the big guys, the local radio station packages looked, well, local. I knew at once that radio sellers could learn a lot from the collection on my office floor. See the discussion of selling radio, in Chapter 8, where I’ll share those thoughts.

The cable systems and networks are selling to a national audience, thus they need the elaborate printing jobs and creative shapes of their presentation packages. They have to dazzle the national agencies and national advertisers every day, and those buyers have seen it all. Most of them work in New York, although some are based in Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, or Dallas—media centers on their own. With all the competition, it can be difficult to get their attention.

When Lee Masters was president of E! Entertainment Television, he called the national buyers “highly sophisticated and highly educated. No matter how much they talk about qualitative (information), they’re concerned about quantitative.” After all, buyers demand proof of strong ratings. For that reason, sellers at the national network level must be skilled analysts as well as skilled sales people. Masters called it “using the numbers to think about numbers. Our seller has to know Nielsen, Simmons, MRI. They’re selling information and research.”

FIGURE 1-9 Logos are supposed to make a statement. This one does it with exclamation. So does the network it represents. You’ll read about E!’s selling in this chapter and the next. In Chapter 3, you’ll read about E! as an example of “signaling” to create a more efficient buy for advertisers. © E! Entertainment Television, Inc.® Used with permission.

“Ultimately, every buy comes down to demo,” Masters said. “Really good sales people want to develop terrific relationships with the buyer, but the buyer takes almost a factory approach.” He refers to selling a network like E! as “putting it out to bid.”

The media kits on my office floor told stories beyond the audiences each facility could deliver:

• NBC combined CNBC, MSNBC, and “the big network.”

• E!, Court-TV, CNN, CBS, Warner Brothers, and lots of others referred to their interactive divisions. Some offered joint presentations.

• A cluster of Watertown, New York, radio stations plugged their Web sites.

• Cox Interactive Web sites combined news, weather, and local data from a Cox-owned TV and radio station, like accessAtlanta.com and WSB Radio and TV.

These are but a few examples of the merging and converging of the electronic media environment.

Every day, there are reminders of how fluid electronic media is as an industry: trade magazines, daily faxes, memos about company performance, sales projections of your medium against competing media. They carry stories of companies emerging from nowhere, ideas taking shape overnight, and mergers changing the competition to cooperative, co-owned properties. You’ll read about the radio industry’s consolidation, and about the new environment for television as HDTV expands both bandwidth and the number of channels. You’ll follow Internet startups sprouting like weeds along the information superhighway.

FIGURE 1-10 A key theme of this book is the merging and converging of media. There’s hardly a better example than NBC’s extension to cable with CNBC business news and to MSNBC’s news coverage on both cable and the Internet. Courtesy of NBC Cable Networks, Ad Sales Department, April 1998. © 1998.

As CEO Diane Sutter of Shooting Star Broadcasting says, “Everybody wants to be in everybody else’s business.” She’s referring to new media being created by combinations of older technologies: content is distributed over the air, by digital broadcast satellite, by cable, by phone lines to cyberspace. Sutter reminds us that “there’s never been a new medium that transplanted an old medium. They just added on.”

Historically, whatever the next medium was, it added advantages to the last medium. So far, no new medium has eliminated the last medium. Mary Meeker put it this way in The Internet Advertising Report, which she wrote for the Wall Street research and investment firm, Morgan Stanley & Co:

Typically, new media have done some key things better than older media. For example, newspapers were better than town criers because the information was recorded; magazines were better than newspaper because they focused on national issues (and had cool pictures); radio was better than magazines because it was live and timely; television was better than radio because it was live, timely, and had cool pictures; and we contend that the Internet is better than television because it provides live, timely, viewable, and often storable information and entertainment when viewers want it, with the powerful addition of interactivity.40

Not only are new media additive, but often cooperative. Radio in the 1940s was pleased to recreate Hollywood films and cross-pollinate its stars, just as early television put pictures to the already popular radio comedy and variety shows.

FIGURE 1-11 Another answer to the question, “What does MSNBC stand for?” is the marriage of Microsoft Network and NBC television. The joint venture gave NBC a new cable channel and a strong Internet presence at www.msnbc.com. Courtesy of NBC Cable Networks, Ad Sales Department, April 1998. © 1998.

Merging and converging is evident everywhere. Today’s TV networks extend their reach with cable and Internet presence. NBC-TV, for example, presented its 1997 World Series post-game analysis not on the major network but on its CNBC cable channel. CBS recycled classic TV programming on its “Eye on People” cable channel. Each of the major networks and most of their key programs maintain Internet sites with interactive polls and promotions. WEB-TV is both a weekly program for over-the-air television and a full Internet domain, supported by Microsoft.

Radio’s deregulation in 1996 yielded unprecedented consolidation through mergers of the largest radio companies into market-dominant clusters. Small companies that couldn’t compete against the mega-operators were ripe for acquisition.

The trade publication Radio & Records’ first headline after the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was “Let the deals begin!”41 The lead paragraph was prophetic: “Buy, sell, or get out of the way.”

Radio Business Report showed 71.4% of radio stations in some consolidated arrangement in the third quarter of 1998, either co-owned with other stations in the market or contracted to a local marketing agreement.42 The mergers of radio companies and acquisitions of new properties was so intense that the daily publication Inside Radio added a weekly edition called Who Owns What as a scorecard for consolidation.

FIGURE 1-12 Both CNBC and MSNBC trade on a very recognizable brand—the NBC Peacock—to carry the message of “NBC leadership.” Courtesy of NBC Cable Networks, Ad Sales Department, April 1998. © 1998.

Radio stocks showed 100% gains in the years immediately following the Telecommunications Act of 1996, while the Standard and Poors 500-stock index increased only 42%.

As Business Week noted, the excitement pushed the stock prices of industry leaders like Clear Channel Communications to more than 18 times the estimates of 1998 cash flow.43 The magazine questioned whether radio could keep its advertising boom alive by grabbing a larger share of Madison Avenue budgets. Radio answered with a resounding “yes!”

Radio’s share of the advertising pie was level at about 6% through the television years. In the 1990s, the share crept toward 7% once consolidated radio companies focused their selling power and increased radio’s sellable inventory.

“Companies that owned ‘A’-level stations bought ‘C’-level stations,” said Gary Fries, President of the Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB).44 “That elevated the industry with better programming and better selling.” Fries credits consolidation of ownership with allowing failing stations to add new, niche formats—jazz, for example—“to raise the level of good, quality inventory.”

Fries admitted that radio’s revenue renaissance was a product of timing. “Radio opened new inventory during a strong economy. If it had happened in 1989, we might not see the same results.” In his estimate, only 70% of radio inventory is utilized, but he acknowledges that overnights and some periods of weekends prevent the medium from selling 100% of inventory.

Can radio increase its share of the total advertising dollar? “Raising the percentage is policy” at RAB, says Fries. “The mission of RAB is growing the business. Seven percent is nothing more than a milepost. Radio can see 7% in their minds. When the industry hits 7% overall, we raise the mile-post and try for 7½.”

Radio revenues from 1997 reached $13.646 billion dollars, $1.2 billion dollars more than the previous year, according to RAB figures. (Note that RAB figures differ slightly from McCann-Erickson’s “official” statistics in Table 1-1.)

FIGURE 1-13 The launch of AMFM was one of the largest new network debuts ever. Before AMFM, network radio reached about 65% of the United States AMFM’s launch took that number to “the mid-80s,” according to Senior Vice President David Kantor. Courtesy Chancellor Media. Used with permission.

Twenty-First Century Television

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 also allowed television companies to expand when the previous limit of 14 stations was eliminated and the coverage cap of 25% of American homes was lifted to 35%. Broadcasting & Cable reported that the nation’s top 25 TV-station groups owned or controlled 36% of the 1,202 commercial stations on the air in 1997, up from 33% in 1996, and 25% in 1995.45

While television broadcasters did not have the ability to own multiple stations in one market, there was a proliferation of local marketing agreements (LMAs), allowing companies to control the advertising sales of one other station. The coverage caps are adjusted for stations under LMA contract and for UHF stations.

‘Are the networks showing their age?” was the headline in Digital Home Entertainment magazine in its first 1998 issue.46 An editor’s note indicated that the original headline was to have read, “The Death of Network TV,” but that the situation was not so clear-cut.

National television networks faced erosion of shares as new media outlets challenged them. In 1987, affiliates of ABC, CBS, and NBC captured 71% of the prime time audience. Cable had but 14%. By the end of the 1996 season, the combined share for ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox had declined to 61 % and cable’s total share had grown to 38%.47

In the summer of 1997, basic cable achieved a 40 share in prime time against only a 39 share for the traditional “Big Three”—ABC, CBS, and NBC.

The founder of USA Networks, Kay Koplovitz, told the Television Critics Association that year that broadcasters “conceded the summer” to cable, leaving “viewers available for easy pickings.” Cable World magazine reported that new cable networks added to the cable pie without cannibalizing established services like CNN, ESPN, TNT, or USA.

The decline of network viewing was accelerated by services like DirecTV, PrimeStar, and other suppliers who delivered programming directly to the consumer, bypassing the local station or local cable operator.