CHAPTER 3

Understanding People and Relationships

People Are the Heart of Services

People Are the Heart of Services

Despite the ability of new technologies to automate and augment people’s daily lives, people remain at the heart of services. As we mentioned in Chapter 2, a service has no or little intrinsic value until the moment of its use or consumption—services or experiences cannot be stored in a warehouse. But “use” and “consume” are product mindset words and we need to use different language for services. People don’t “use” a healthcare professional or a lawyer, and they don’t consume a train journey or a stay at a hotel. Instead, people enter into a relationship with professionals and service providers, and their interactions are an act of co-producing the service experience. Thus, we need to think in terms of designing for relationships and experiences that evolve and change over time, rather than just in terms of short moments of consumption or usage.

In the age of self-service Web booking and mobile applications, interpersonal experiences would seem to be on the way out, but services comprise interactions among people, technology, and processes. When these are industrialized and institutionalized, as often happens when organizations grow, they need rehumanization to work properly and connect back to people’s human experience of the service. Even human-to-human interactions need this kind of design attention when they are mediated by technology, such as call center interactions or even forms.1

It is essential to understand that services are, at the very least, relationships between providers and customers, and more generally, that they are highly complicated networks of relationships between people inside and outside the service organization. The staff who interact with customers are also users and providers of internal services. Most people have tales to tell of how inflexible their IT departments are or how other company policies curb their ability to innovate or provide the service they know their customers want. IT staff respond with stories of how other staff—their “customers”—sap their time with questions and problems that are blindingly obvious (to them). When frontline staff are let down by internal systems and procedures, they become disempowered and inflexible. This is passed down the line and leads to poor customer experiences and service failures.

Industrialization did not just lead to industrial product thinking. We argue that the industrial mode has also led to the stereotypical “faceless corporations” that are often the subject of frustration and poor experiences for service users, because the industrial mindset is usually all about efficiencies and economies of scale rather than effectiveness of the delivered service. Some customer–provider relationships can end up being toxic and combative, and as the history of human warfare shows us, people tend to dehumanize the enemy.

All decisions in an organization stem from people, and in some form or another, other people interact with them and are affected by them. We are more often aware of this with government policy decisions, but the human outcome is frequently overlooked when business discussions include terms such as “consumers” or “target groups,” or worse, simply focus on numbers on a spreadsheet.

This industrial mode is inefficient and ineffective for services. As soon as we forget that people—living, feeling, emotive human beings—are involved throughout the entire chain of events, not just at the moment of use by the customer, things go wrong. Organizations can end up being aggressive, manipulative, and aloof, and customers may feel that the only channel available to them for venting their frustration is an unfortunate, underpaid call center employee, who is also bound by rules and regulations and may have had a pretty bad day herself.

The successful businesses and public services of the future will foster a more equal and reciprocal relationship with their customers, one that recognizes the customer as a co-producer of the service.

One of the tools we cover in Chapter 8 simply asks, “How likely is it that you would recommend our company to a friend or colleague?” while another measures the gaps between people’s expectations and experiences. It is noticeable here that the main things we are trying to measure are people’s relationships to the service and to each other, not efficiency metrics. Services usually involve staff to deliver them, but many are really platforms for creating interactions between other service users. Social networks are, of course, the most high-profile example of this, but some services, such as eBay, are a mix of the two. Issues such as trust, credibility, empathy, and tone of voice are important for many services to thrive. Understanding not just people as individuals but also the relationships they have to others is essential to understanding how a service might operate.

A good example of this relationship building is Zopa, a peer-to-peer lending service that has dramatically altered the customer relationship mode of a financial service. By giving people the ability to network, and by gaining insights into their needs, motivations, and feelings, Zopa is not just another lending and borrowing service. It is a social community with a sense of reciprocal responsibility, something that has certainly been long absent in the mainstream banking world (see Chapter 6 for more on Zopa).

To put people at the heart of services, we need to know who they are. We need to listen to them and obtain accurate information that helps us give them what they need, when they need it. We start by gathering insights.

Insights versus Numbers

Service design draws upon the user- and human-centered design traditions as well as the social sciences to form the basis of our work gathering insights into the experiences, desires, motivations, and needs of the people who use and provide services.

Although the business press makes a lot of noise about “putting customers first,” being “customer centered,” and having “a customer focus,” few organizations employ this form of knowledge with the same rigor that they employ accounting and law. The latter are usually legally mandated for organizations, of course, but developing and maintaining a deep understanding of the people for whom an organization exists to provide value is just as important for the ongoing relevance and survival of a business. Service design is not simply something to add on top of a business proposition after all the numbers have been crunched; it is fundamental to the entire organization and its offerings, and can create a paradigm shift in corporate culture and thinking to one of sustained value and innovation.

All types of organizations have the potential to personalize services and create huge benefits for themselves and their customers. From personalized learning in education to insurance quotes tailored to a policy holder’s driving style, personalization is a powerful concept. Shifting attention from the masses to the individual enables radical new opportunities, and because of this fact, service design places more emphasis on qualitative over quantitative research methods.

Service design involves research across all the stakeholders of a project—from the managing director to the end user, and from frontline staff to third-party suppliers. Of course, other disciplines focus on detailed knowledge of customers as a business advantage. The most notable is marketing, and indeed, “insight” is a term widely used in marketing. We are not suggesting that service design is an alternative to marketing, and we acknowledge that service design draws upon a number of disciplines for some of its methods and approaches, but we want to explore how the specific emphasis on design creates value in the experience of services, service propositions, and touchpoints.

Marketing excels in understanding markets and how to reach them through the classic four Ps: price, promotion, product, and place. We are focusing on the fifth P, people, and how we work with people to inform the design of a service.

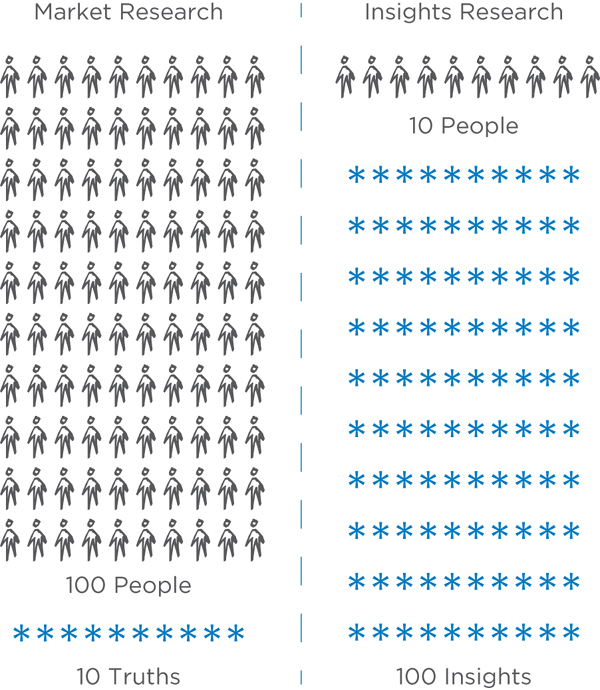

Market research is typically quantitative and prefers large numbers of respondents. This research can yield some “truths” that are statistically significant and correct, such as the percentage of people who use a certain kind of service (Figure 3.1). This background information can be useful, but discovering through quantitative research that 70% of people do not ride a bicycle (to use a fictional statistic as an example) does not give us any hints about why they do not ride bicycles. Statistics are not very actionable for designers—we need to know the underlying reasons.

FIGURE 3.1

One is not better than the other, but for our purposes, qualitative research yields more useful insights that we can use as a basis for design than quantitative research’s “truths” do.

Qualitative research helps designers dive deeper to understand the chaos and emotions that make us human and behave in seemingly illogical ways. We are interested in people’s needs, behaviors, and motivations because these can form the basis of design problems that we try to tackle as designers.

Maybe the non-cyclists in our example prefer the car or bus, or maybe they do not cycle because their city has inadequate bike lanes and the risk of an accident overrides their desire to cycle. If we only work with the statistics, we might assume that the bicycle market is only 30% and decide that it makes more sense to concentrate our efforts on designing better cars and buses. Of course, this choice would likely lead to even fewer bicycle lanes and fewer cyclists. Knowing people’s motivations for not riding bicycles, and understanding the behaviors of those who do, means we might instead focus our design effort on rethinking traffic zoning and bicycle services, as the city of Copenhagen has been doing with great success.2

Using Insights to Drive Innovation

Service design and innovation go hand in hand. Much of the work involves shifting clients from an industrial mindset to thinking in a service paradigm. This may mean spending a lot of time helping clients develop an internal culture that will serve them well when it comes to facing future challenges.

Service designers employ the same tools and methods whether they are engaged in innovation work or improvement work, but the purpose of insights is different in each case. By innovation, we mean introducing a new service to a market, or even developing a new market. In this mode, the primary concern is to reduce risk by making sure that the value proposition is viable. The purpose of the research is to generate insight about needs and behaviors that can lay a solid foundation for a productive project and robust ideas, and to confirm these by prototyping early and often to test them out.

Innovation work can be excitingly blue sky and often requires thinking outside of the current norms, but the danger is that it can become distant from people’s real needs and problems. We are still waiting for our flying cars and jet packs, and this is probably a good thing because both would most likely result in enormous carbon footprints and crazy sky traffic. If people are asked to dream up their ideal fantasy of transport, they would likely say they would love a flying car or a Star Trek transporter. Beyond fulfilling childhood fantasies, however, the underlying need of these suggestions is simply an efficient and engaging transportation experience, or even avoiding travel altogether. Innovation brainstorms can easily end up being driven by technological or marketing fantasies. By asking people about their everyday experiences and observing what they do, how they behave, and what their motivations are, we can ground the innovation process with insights into people’s actual lives.

In the end, insights that drive innovation confidently answer the question: “Will our offering make sense in the context of people’s lives, and will they find it valuable?”

Many service design projects are about improving an existing service, and here the insights research focus is slightly different. If a service already has many customers, and competitors have entered the market, one can assume that people understand how the service is used and that it is of value. In these cases, the focus is on discovering points of failure in the service (known in service design jargon simply as “fail points”) and opportunities for enhancing the experience. This focus means that we can narrow the research scope and look less at unfulfilled needs and more at usage in context. It also means that operational data become a valuable resource and that customer-facing staff are a gold mine for insights. Staff usually can identify most of the problems customers face with a service, although it can be more difficult for them to pinpoint the opportunities for thinking outside the box. When time is short and a service improvement project has a limited budget, it is often a good idea to prioritize the research time with staff and data to dig quickly into the detail that is needed to design great services.

Obviously, these two areas overlap. Improvement may happen through small innovations, or a blue-sky innovation idea may be scaled back and the principles applied to an existing service or touchpoint as an improvement. What changes is the focus of what we are trying get out of the insights research. In either case, the focus is always on people.

Designing with People, Not for Them

People are part of the delivery of services in a way they are not with products. Consumers probably do not know who designed or built their car, for example, but they will have some contact with the person they speak with at a call center or with the nurse who admits them into an emergency ward. We need to design service elements as much for the person who delivers service as we do for the customer.

Service design is about designing with people and not just for them, and it is here that it differs from classic user-centered design and much of marketing. “People” does not just mean customers or users, it also means the people working to provide the service, often called frontline, front-of-house, or customer-facing staff. Their experience, both in terms of their knowledge and their engagement in the job, is important to the ongoing success of a service for two key reasons.

First, in very simple terms, happy staff equals happy customers, so their inclusion in the design of services ensures that providing the service will be a positive experience. Staff who are involved in the creation and improvement of service not only feel more engaged but through learning about the complex ecology of the service they provide and how to make use of innovation tools and methods, they are also able to continually improve the service themselves.3 Service innovation should have a life span beyond the length of time the service designers are involved in the project. This means recognizing that other stakeholders may engage in many of the activities of service design as part of a continual process of change.

Second, along with customers, frontline staff are often the real experts. They provide insights into the potential for service design that are frequently as valuable to the project as insights from customers, and they can provide a perspective on the day-to-day experiences that managers and marketing people may never experience.

Working across Time and Multiple Touchpoints

For designers who come from a discipline that already uses human-centered design methods, much of this material will be familiar. Understanding people and their daily lives and needs provides the central insights on which many design projects are built (in an ideal world). The difference between service design and product or UX design, for example, is that the number of stakeholders we are designing for is usually larger, the number and range of touchpoints broader, and all of these interact over time.

Segmentation by Journey Stage versus Target Groups

In our definition of service design, we talk about experiences that happen over time. It is relatively simple to gain insight about an experience that happens in a short amount of time, such as an online purchase or a patient’s consultation with a doctor, but how do we gain insight into experiences that change and evolve over years or even decades?

In product design or marketing research, we would typically segment the market and interview people in different age, socioeconomic, or behavioral groups. In services, a more useful way to engage with people is by looking at different stages of their relationship with the service. This strategy allows us to research the different journeys people might take through a service and how they transition through the various touchpoints.

Researching across Multiple Touchpoints

Unlike many products or screen-based interfaces, services do not lend themselves to lab testing. For a start, services usually involve large infrastructures, and it would be difficult to test a complete train journey without a rail network infrastructure, although we can prototype elements of it. More important, people interact with services through different channels in different situations that often include interactions with other people. Context is critical to gathering insights into people’s interactions with touchpoints, and a lab is not a context in which this can happen (unless the project involves scientists).

For example, one day a customer might buy a train ticket online, another day from a counter in the station, and the next day from a ticket machine or on the train. In addition, the ticket-purchasing experience is closely connected to pricing, route, and departure information, the signage in a station, how staff deal with questions, and the quality of the train ride itself. Third-party services that connect to the train ride also play important roles, such as buses and taxis, credit cards, maps, cleaning services, and the café where travelers can comfortably wait and grab a bite to eat.

From a service point of view, we are really after understanding how different touchpoints work together to form a complete experience. Therefore, try to do research with people in the situations where they use the service. Study how people use a service at home, on the road, and at work, and then connect the dots.

In addition to looking for latent and explicit needs and desires, as is commonly done in most design projects, also look closely for service-specific insights. Look for touchpoints that may be missing but are needed to create a good experience, or touchpoints that are superfluous. Look for situations in which the service could play a more valuable role, or instances when it is smart to keep people from noticing that it is there.

What is most important to look for is variation in quality between the touchpoints and the gap between expectations and experiences. When people get what they expect, they feel that the quality is right. Whether it is a premium or a low-cost service, a minimal gap between expectation and experience means greater customer satisfaction.

All of this can be much more difficult than it sounds and can get very complex very quickly. There are natural and economic limits to what we are able to influence, and if we try to track every touchpoint, we will end up trying to re-create the world. A car-sharing experience might happen in the context of a city, so we might want to look at parking spaces, which means we end up dealing with city government, and before long we are wrestling with the entire country’s traffic infrastructure policy. Thus, it is important to be strategic and decide on the scope of your insights research. The grumpy café owner in the train station is probably not a touchpoint that we can work on if our client is the rail company, although we might try to find out why the owner is so grumpy and ruins travelers’ days (perhaps the rent the rail company charges him is too high). On the other hand, he might have wonderful insights into travelers’ confusions because he gets asked where the station exit is several times a day.