CHAPTER 1

Insurance Is a Service, Not a Product

Putting Insights into Practice

Experience Prototyping the Service

Insurance rarely comes to mind as an industry that provides a rewarding customer experience. The only time people find out whether their insurance company is actually any good is when they are at their most distressed and vulnerable. When they find out their insurance is awful, there is nothing they can do about it. They are at the mercy of small print they either did not read or did not understand, and they may end up spending hours on the telephone or filling out more paperwork. There should be insurance against mistreatment by insurance companies.

For many insurance companies and the people working for them, the lofty goal is to be the least awful with the minimum effort possible. The insurance market has ended up in a race to the bottom, competing only on price because customers do not understand their complex policies, hence the proliferation of insurance price-comparison websites.

Part of the problem is that insurance is complicated, involves multiple stakeholders and channels, and is a classic example of a service that is often sold as a product. The mix of complexity, human experience, multiple stakeholders, and delivery channels, combined with customer dissatisfaction with an industry stuck in its ways, makes insurance a perfect candidate for disruptive service design.

In 2009, Norway’s largest general insurer, Gjensidige (pronounced yen-SEE-dig-ah), decided they had had enough of competing in this toxic marketplace on the same level as their competitors. As a financial group with a 150-year history, Gjensidige had a solid position in the market, but they had a strong drive to improve the quality of service they were offering their customers. CEO Helge Leiro Baastad decided that customer orientation should be a main strategic focus and a key competitive advantage for the firm.

A major challenge was a structural one. Gjensidige was organized as a chain of activities from product development to sales, with expert staff working in silos. This industrial model made it difficult to orient the silos to work together to deliver a unified experience to customers. Because Baastad wanted the change to be driven from the heart of the business, he asked marketing director Hans Hanevold and brand director Kim Wikan Barth to leave their jobs for two years to run a company-wide change program called “Extreme Customer Orientation.” Both Hanevold and Barth had long track records with the company, enjoyed the respect of their colleagues, and knew how to engage the organization.

Hanevold and Barth began by identifying change agents in every business unit within the company. The underlying principle was that customer orientation should be grown from the inside out rather than being driven by outside consultants, and that the activities should be funded by the business units themselves. To support these activities, they created a company-wide training program, then set about identifying what ultimately amounted to 183 concrete actions to improve customer experience. For some projects, the business units required specialist expertise to fulfil their ambitions, and service designers were hired to help design a better service experience.

Gjensidige embraced service design as a way to help bridge the gaps across the silos and develop their services in more customer-oriented ways. Service design methods helped them create a complete and shared picture of what really provides value to the customer, as well as processes to join up the experiences.

As a lead-up to their change program, Gjensidige employed service designers to challenge their thinking about what the ideal insurance service would look like. The initial task was very broad—Gjensidige wanted to find out about people’s behaviors, motivations, and relationships to insurance. It was important, however, not only to understand the mindset of Gjensidige’s customers, but also of staff.

The actuaries—the mathematicians and financial wizards who come up with the complex “products” on which insurance is based—belonged to the Product Group. The name of this department was a clue to the shift that was required in the company’s internal culture. What the company is really selling is a service. Customers cannot hold insurance in their hands, and their experience of their insurance policy is made up of the service interactions they have with the company. When customers buy a physical product, they can inspect it for build quality, flaws, or damage. It is much harder to do that with services, especially ones that are essentially a contract based on the chance of a future event, such as insurance. Many people buying insurance do not really know what they are buying, and only find out what is covered at the worst possible moment—when disaster strikes. This is not the time to begin haggling over contract details.

Consumer Insights

The approach taken in the Gjensidige project is an example of classic service design—insights research, workshops, service blueprinting, service proposition development, concept sketches and presentations, experience prototyping, testing, and delivery. A fairly small sample of users was involved in the research, but the research went deep. The design team visited and spoke to three people working in Gjensidige’s call centers and offices, as well as six customers, to look at both the delivery side and the recipient side of the service. To people used to working with larger data samples, nine people might not sound like enough, but Gjensidige already had a great deal of quantitative information. This information didn’t have the detail of the qualitative research needed for an innovation project, however. Quantitative methods are good for creating knowledge and understanding the field, but they are not very useful for translating knowledge into action and helping organizations do something with it. Qualitative studies are very good at bridging this gap.

Five different areas were researched with the participants: insurance in general, social aspects, choices, contact, and tools for staff. What Gjensidige and the service design team discovered were some important differences between what people say and what they do. Some of the insights that were uncovered are described below. Many are questions and needs, and one can see how this kind of research immediately gets the problem-solving juices flowing.

Trust

Insurance is built on trust. When customers pay their premiums, they trust that they will get value for money—and that the insurance company will still exist when they need it. But trust is very fragile. It takes some time to build up and is quickly broken. All the small glitches in delivery—letters sent to the wrong address, billing errors, problems with communication, customers having to repeat details multiple times—damage people’s trust in an insurance company. They wonder whether similar chaos happens behind the scenes. Fixing the small glitches can have a big impact on the level of trust.

Comparison and Purchasing Criteria

People say they make insurance purchasing decisions based on quality, but they find it hard to do this in reality. It is very difficult to compare what is inside different insurance policies and make a rational choice. People feel that insurance is not very transparent, especially with regards to quality, so it is easier to compare on price, because money is a fixed variable. This means designers cannot simply trust what customers say they want, but have to work smartly around price and quality issues.

Of course there is room for quality in the market, but with online price-comparison engines, the quality aspect of insurance has completely dropped out of the conversation with customers and all that is left is price. For customers, quality means, “Am I covered? Do I get a rental car when my car is being repaired? Am I actually covered for the things I think should be covered?”

With most other services and products, customers can easily see the differences between the premium version and something cheaper, but not with insurance. Customers are really asking what quality means—that is, the difference between the premium and budget products. This raises many other questions, such as what is actually covered and when, how much are the out-of-pocket expenses, and so on. It soon becomes complicated.

As with much service design, the challenge is to make the invisible visible, or to make the right things visible and get rid of the noise in the rest of the offering. In the Gjensidige project, then, one of the key challenges was to develop a service proposition that eliminated price as the key deciding factor.

Expectations

People expect an insurance payout when something happens, and they expect help. This is another issue related to quality. Customers who buy a cheap insurance product get money but will not get much help, whereas Gjensidige has a very good system for taking care of people when something happens. For example, when customers have damage to a car, they just take it in for evaluation and Gjensidige issues a rental car and takes care of everything else. This fact needed to be made visible as part of the service proposition.

Employment and Public Benefits

Gjensidige believe they provide all the insurance people might need, but in Norway many people are also covered by some kind of insurance from their employer or union. It is very difficult for people to tell whether they are covered because there is no way for them to see all of this information in one view, all in one place. The challenge is to achieve this in a transparent and trustworthy way for customers.

Social and Cultural Interactions

Many invisible social touchpoints affect the entire service experience. The police, for example, might give insurance advice by saying, “Oh, your cell phone was stolen? Don’t even bother contacting your insurance company.” Customers who contact Gjensidige do in fact receive a new phone, but people tend to trust that the police are knowledgeable about such issues.

The researchers discovered that many different people were giving advice about insurance who should not be. For example, friends and family were frequently believed to be the best source of insurance advice. People trust their father to give them good advice about an insurance policy more than they trust an insurance agent. (By “agent” here, we mean a representative of Gjensidige because there is very little in the way of an insurance brokerage market in Norway.)

The challenge, then, is how to work together with all of these invisible touchpoints. Insurance originally dates back to a time when people in a small community would pool their money to pay for an accident, such as someone’s barn burning down. This stimulated thinking about bringing back this social aspect, because insurance had evolved from a collective effort into these machines that customers don’t trust.

Choice

From an insurance specialist point of view, the more options you have the better you will be covered. Covering certain items, such as a new bike, but not others, such as an old PC, allows people to have insurance tailored to their needs.

At the same time, customers want simplicity. The paradox discovered in the insights research was that customers want very simple products, but they want to feel like they are making a choice from an array of complex products. The underlying need here is that they do not want to have to choose from lots of options, but they want the experience of having made their own choice.

Documents

When it comes to reading insurance papers, one of the typical quotes from interviewees was, “I just can’t do it.” This connects back to the issue of trust. On the one hand, customers do not read the details of their insurance policies, which means they blindly trust the insurance company to be right. On the other hand, customers do not trust the insurance company because they do not know the details of their policies.

Insurance companies produce enormously long documents, which is the main reason customers do not read them. Customers were saying, “Can’t we have just one document and could it be on one page?” but what people actually wanted and needed was a “What if?” structure they could study—one to explain that if this happens, the customer will get that from the insurance company.

Customers also had no idea where they kept their insurance papers. They know the papers are important and some people said they had them securely filed away, but when researchers asked to see them, the papers were in a complete mess. Interviewees would say, “Yes, they’re just over here,” but it would turn out to be a policy from two years ago and the latest one was still in a pile of papers somewhere. This means that customers have no clue about what they are insured for or what they are even paying.

Another reason people did not know what was in their documents is that most of the text is written by lawyers in “legalese.” Over the years, more and more text had been added to these documents without much serious thought about what was still needed. To counter this, Gjensidige reduced the size of their insurance policy documents by 50% to 60% just by taking out extraneous words and simplifying the language as much as legally possible. It took a team of four people a year and a half to do this, but they have done a brilliant job. Gjensidige also gained a small side benefit from reduced printing costs, but the big benefit has been in customer experience.

Company Insights

Filling In the Gaps in Public Benefits

In Norway, people assume that if something bad happens to them, they will be covered by the state, but they have no clue about what actually would be covered and what they should cover themselves. Customers need this information and they need people to talk to who can give them good advice, not just salespeople who are more interested in selling an insurance product than in what customers need.

As in many organizations, the underlying issue is hard targets for sales quotas and organizational structures that actually discourage customer service representatives from taking proper care of people. Gjensidige needed to change the way they measure performance internally so that the benefit could be experienced externally, which meant an internal culture change. Since this change was implemented, everyone’s primary measure is customer satisfaction on an individual basis. Customer-facing staff at Gjensidige get daily reports on their own customer satisfaction scores. The main data is gathered by sending customers an e-mail asking if they want to rate their experience after every customer contact by telephone or at a branch office. This feedback is added to a mix of other metrics to make up a comprehensive customer experience measurement system.

Being Personal

When it comes to customer relations, people see straight through things that are meant to be personal but actually are not. Humans are so well attuned to interpersonal interactions that communications such as “personalized” form letters can come across as almost creepy. Worse still, these kinds of faux personal communications are prone to simple glitches, such as old data or typos, leading to personalized life insurance letters being sent to dead relatives, or Mr. Jones being addressed as “Dear Mrs. Jones.” There is only one type of personal, and it is to be genuinely personal. For that to happen, of course, the company culture must be one that encourages it and one in which employees feel happy working. Grumpy, stressed people have grumpy, stressed interactions.

Consistent Communication Channels

Respondents wanted Gjensidige to stay on their channel, meaning that if they telephoned, they wanted the company to call them back, not send an e-mail or a letter. If they sent an e-mail, they wanted an e-mail back. Gjensidige made the strategic decision to keep all of their channels open, which is more costly because it is more complicated to manage, but the company believes it is worth the expense because it creates a better customer experience.

Language

Laypeople (customers) really do not understand the language of insurance. A lot of people thought a “premium” was actually a prize, for example. As such, Gjensidige needed to be careful that the insurance language that is clear to them actually means the same thing to their customers across all communication channels.

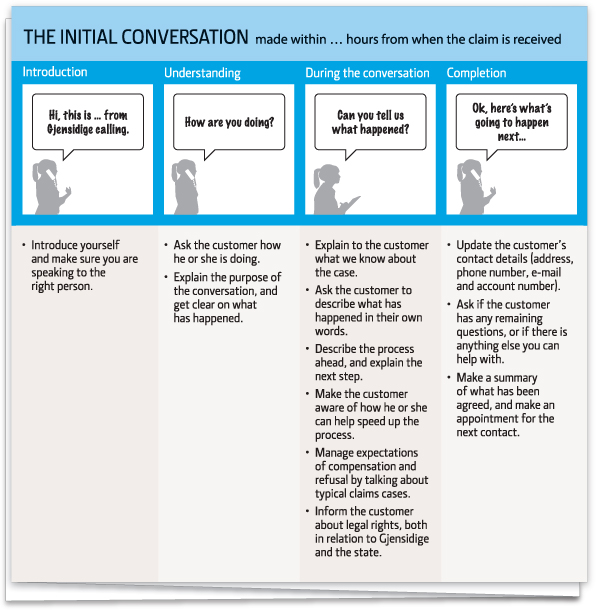

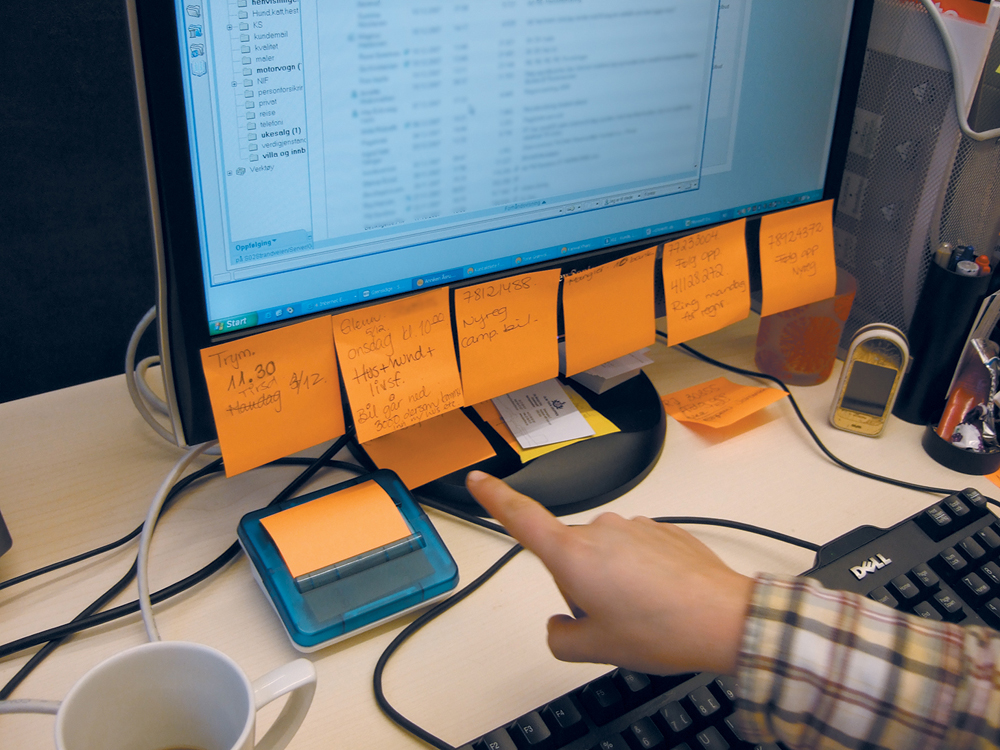

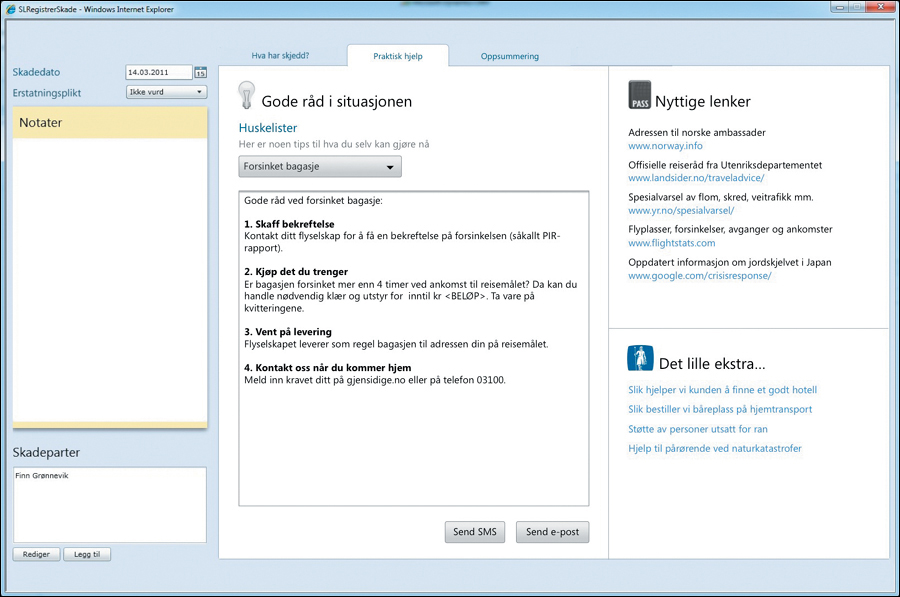

Formalizing Personal Routines

When researchers visited Gjensidige’s offices to interview staff, they saw a lot of sticky notes on salespeople’s desks and on their computers (Figure 1.1). Many people had created their own routines for more efficiently dealing with customers. The insight here was that some of the processes developed “on the shop floor” could be adopted and integrated into Gjensidige’s systems as standard approaches.

FIGURE 1.1

Sales staff build their own routines to make their process more efficient.

Redesigned processes deeply founded on insight from customers and staff were initially implemented as paper-based routines to avoid waiting for enterprise software to be developed (Figure 1.2). Later, these new routines were built into Gjensidige’s new customer relations management (CRM) system (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.2

Paper-based routines were a quick fix for sales staff.

FIGURE 1.3

The new routines were added to the CRM system. A field for customer-specific notes (on the left) functions like a sticky note.

Simplifying IT Infrastructure

All of a customer’s details are entered into Gjensidige’s S2000 mainframe system, which crunches through the numbers and risk analysis in the actuarial tables to produce an insurance offer. Management said that it was the most brilliant system in the insurance industry in Norway. S2000 is very flexible, which means salespeople can manipulate more parameters than Gjensidige’s competitors, but salespeople did not see an advantage in this flexibility. It was too hidden, and in their conversations with customers, the salespeople realized they did not need this flexibility.

Such a flexible system also has the overhead of being more complicated. For instance, a customer could not have a house and a car bundled up in one insurance product. This made it more difficult to create a joined-up experience for the customer.

Putting Insights into Practice

One of the things that hampers product innovation in insurance is the time delay. Organizations only find out whether an innovation will make or lose them money after they see the level of claims, which can take several years. Thus, the insurance industry traditionally is conservative about innovation. The customer insights gathered by the design team helped inspire confidence in bringing new ideas to market.

Using the material from the insights research, Gjensidige ran co-design workshops with different groups within the company and generated 97 ideas, five of which were chosen for further development. Finally, the team came up with one new service proposition.

Gjensidige had about a dozen products for everything to do with people, from individuals to families. From an insurance point of view, this meant that they had a fantastic array of tailor-made products for different eventualities. From a customer point of view, this meant that people felt like they were faced with impossible life insurance choices, such as gambling whether they would die of cancer or in a car accident, because nobody could afford to buy all of the policies and be 100% covered. Customers faced the same dilemma when choosing which possessions to insure—the dog or the laptop?

The breakthrough concept for Gjensidige was to go from offering 50 products to just two: one to cover the individual and his or her family, and one to cover everything they own. From an insurance point of view, this was very radical, but in an example of the value of the expertise that exists inside organizations, the basic idea came from Gunnar Kvan, a very experienced Gjensidige actuary, during a series of design workshops. He suggested that it was possible to think about the company’s offerings in a dramatically different way. He had been working on this idea for five years, but had not been able to get people to see his point. He had no way of expressing his view in terms of what it would mean as an experience for customers, but he knew the financial algorithms could be modeled differently. The design team sat down with him and went through how such a service could be put together. It would require hard-core mathematical engineering in a huge spreadsheet running in the background to make it happen.

Experience Prototyping the Service

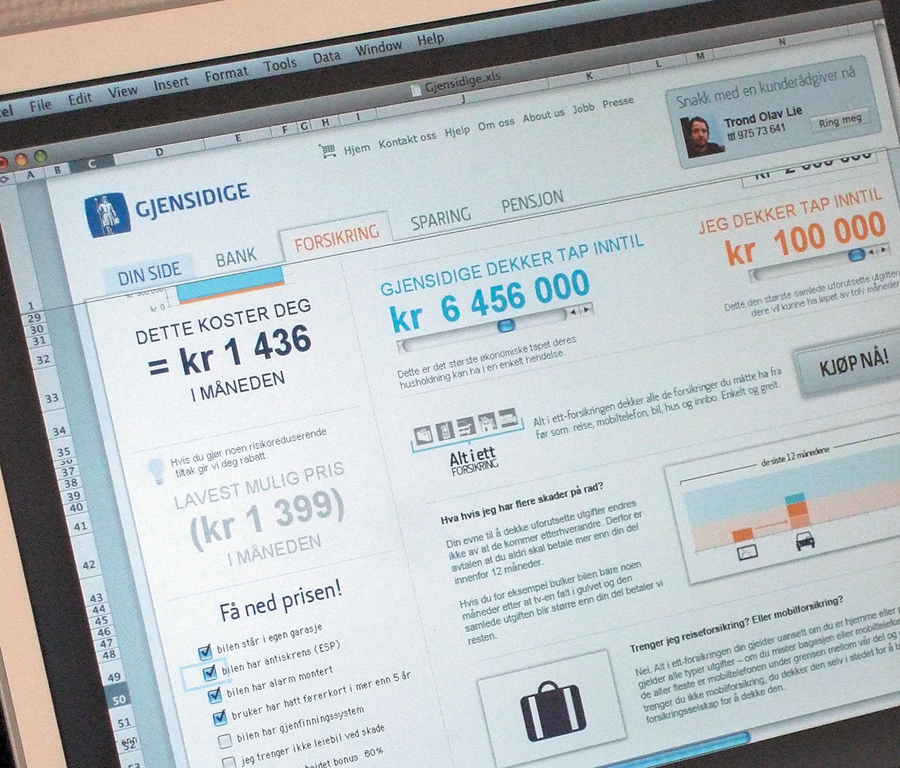

Anders Kjeseth Valdersnes, the design team’s Microsoft Excel maestro, built a prototype of the product in Excel, which had all the tools required to handle the actuarial tables and live information visualization. Rather than spending a week or two designing and coding a Web prototype with a functioning back-end database, Anders did it in two days and designed it to look like a website so that it could be tested with customers (Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4

An experience prototype of the insurance website built in Excel so that the real data could be used when testing with customers.

With this prototype, Gjensidige were able to carry out experience prototype testing with customers discussing and buying insurance, a salesperson selling insurance, and someone trying to make a claim. They tested what it was like for customers to try to buy the services face to face and what it was like for the sales staff. They also tested this process over the phone and observed the process from both sides of the call. To test the claims process, they went through the material with someone who had just had an accident. Actual staff and actual customers took part, and even though they knew they were taking part in testing, the conversations they had were very real. Through this process, the project team learned a lot about what needed to be done to shape, explain, and sell the new service proposition.

It was clear from the prototyping that the new approach changed the conversation from being about buying products to one about service. It meant that customers considered what they could afford on a monthly basis, taking into account what they earned, what was in their “rainy day” savings account, and what they would need in the event of a tragedy. They were able to see the difference their decisions about excess and payout levels made to their premiums, and the conversation was much more open, with the customers in control.

A series of touchpoints were prototyped—the one-page contract, informational leaflets, fake advertisements in a financial newspaper and a tabloid newspaper (Figure 1.5), and the bill customers would receive at the end—so that a broad range of the service experience could be tested.

FIGURE 1.5

Creating fake newspaper ads—one for a financial broadsheet, the other for a tabloid—helped the team understand how the marketing of the service would feel in different contexts.

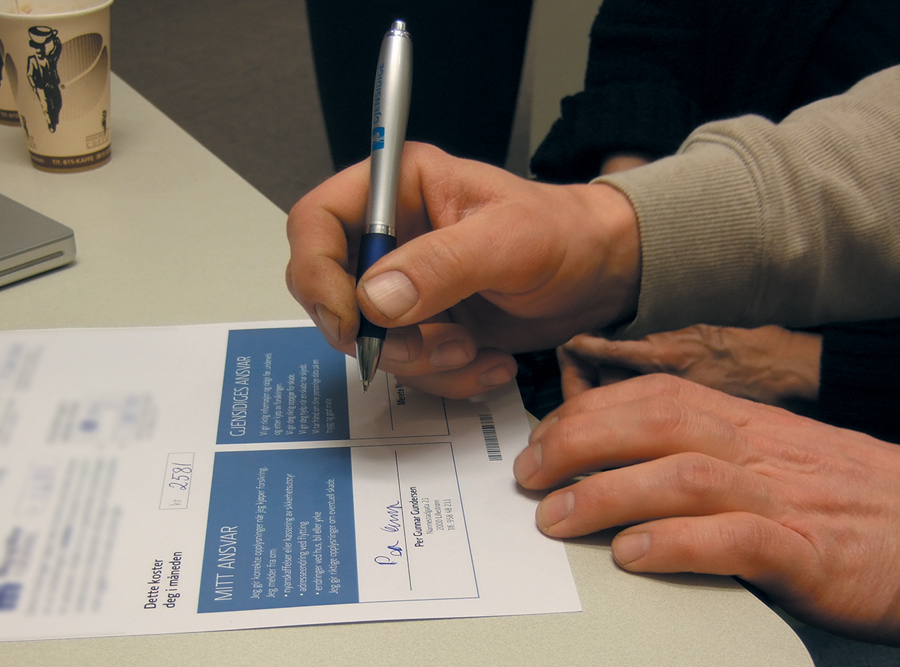

The one-page contract prototype was a good example of the difference between what people say and what they do (Figure 1.6). Many interviewees said that they did not read long contracts and thus did not know what was in them, leading to a lack of trust in the insurance company. They suggested that a one-page contract would be much friendlier. During prototyping, however, it turned out that customers did not trust a one-page contract either, fearing that too much important detail was hidden from them, as their previous policies had been about 40 pages. Gjensidige ended up creating contracts with around 5 to 10 pages.

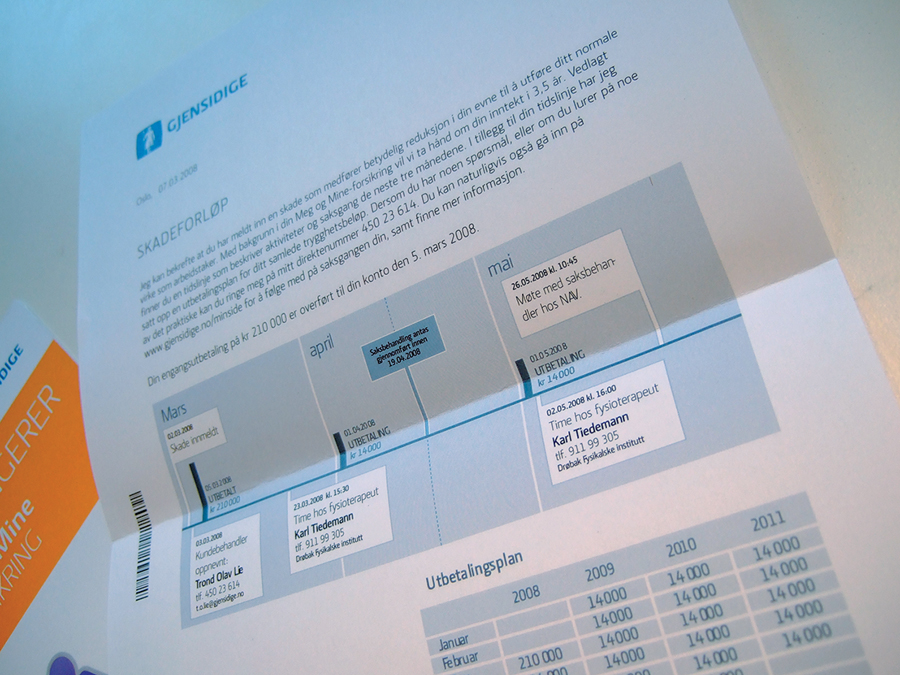

Prototypes were also made of the claim process confirmation documents. Traditionally, customers simply received a letter stating, “We have received your claim,” which left them uncertain about how the claims process was handled within the company. The redesigned confirmation shows the customer how the process unfolds over time and helps to manage their expectations (Figure 1.7). This way they know when to be patient and let the process take its course, and when they have cause to follow up.

FIGURE 1.6

A prototype of the one-page contract so many interviewees claimed they would prefer. Evidence showed that they did not trust it.

FIGURE 1.7

A prototype of a redesigned claim confirmation. This document manages customer expectations by illustrating how the process unfolds over time.

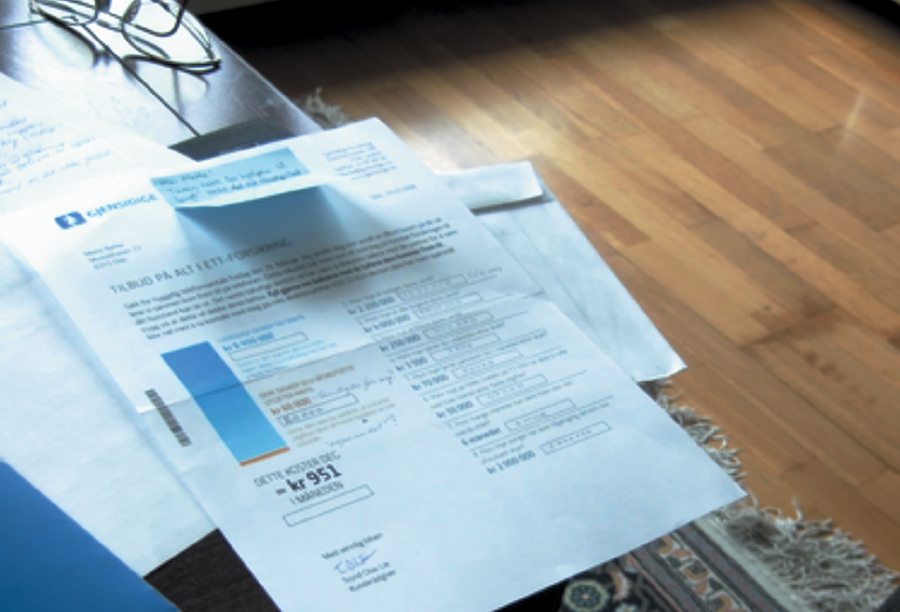

Lastly, the team prototyped an offer sent out in the mail after a sales call or meeting (Figure 1.8). The insights research showed that this was one of the most crucial touchpoint failures, and the company did not realize the potential of improving it. Previously, customers had an interaction with a salesperson in which they talked through a complicated policy, then would go home and explain it to their partners, but could not remember the details well enough to explain it. Because they could no longer understand it, customers could not make a decision. Redesigning this touchpoint helped people make a decision at home, and the company avoided losing customers because of this hidden problem. This is a good example of how services are created and experienced by interactions between people, often in a completely different context than the usual customer-provider paradigm.

FIGURE 1.8

A prototype of the mailed offer, which is an important touchpoint for customers. This document serves as the focal point for discussion and making a decision. This prototype shows an offer that could be revised by customers before the contract is signed.

The End Is Just the Beginning

The value of gaining real insights from all stakeholders—customers, staff, and management—is only half of the story. Translating these insights into a clear service proposition, and experience prototyping the key touchpoints, are essential. This process allowed for feedback not only on the design of the physical touchpoints themselves but also on the entire service proposition and experience. For the designers and for Gjensidige, it was important to know how something so radical would be perceived in the marketplace. The prototypes were created to test unknowns—for example, Was this a low-end or a high-end offering? The two types of newspaper advertisements helped reveal how the marketing of the service would feel in those different contexts.

Services are usually complex and expensive to roll out. In this case, such a radical change to Gjensidige’s offering was not just radical for them, but for the whole industry. It was also clear that it would take a lot of explaining to introduce the concept to their existing, loyal customers. In fact, having only two types of insurance turned out to be too radical even for Gjensidige and the way the entire industry works. This ending might have taken the wind out of the sails of this story, but there is an important innovation lesson to take away from it.

Thinking through radical ideas and prototyping the experience of them helped mature the cultural mindset within the company, and many of the insights have fed into Gjensidige becoming a totally service-oriented company. The Extreme Customer Orientation team acted as champion for the customer experience and the internal changes that needed to happen to deliver it well. A company-wide framework for customer orientation called the “Gjensidige Experience” was implemented. Management understands that this will be a key competitive advantage in the future, building on their vision that “we shall know the customer the best and care the most.”

Gjensidige made extraordinary efforts to simplify their insurance policies. They have worked hard to explain the claims process better and have developed a Web-based claims-mapping tool. Pricing has been worked out differently and is now fed into their online calculators. Although the big idea was not used as a whole, many of the small elements have now fed into the company in very concrete ways. Having the big idea helps bundle together lots of smaller, disparate innovations that would not otherwise have seen the light of day. It also helps challenge organizational traditions that may be holding back innovation.

Finally, mapping out the big idea in detail gives organizations an overview of problems and opportunities all in one place, which helps them make strategic decisions about what to deal with when, how those decisions relate to other parts of their business, and how to scale their service innovation up or down according to budgets and resources.

Gjensidige’s 183 activities is a very large number of improvements. Some were small; others were large undertakings rolled out over several years. The bottom line is important, of course, but it is not the sole focus. The change process required top-level leadership in all aspects of the business, from committing to quality in their computer systems by removing glitches, to simplifying their products and language, focusing on the service experience as well as internal funding, and paying attention to branding, education, and measurement.

For example, 130 Gjensidige managers, including the CEO, gathered their own insights by calling 1,000 customers (Figure 1.9). They loved it, because they realized they had not spoken to customers in years and it was often these interactions that had sparked their interest in the business in the first place. Managers were deeply familiar with their statistics about customer satisfaction, as well as the challenges that needed to be addressed. But it made a real difference to experience for themselves how many customers said they really liked Gjensidige, and to feel people’s emotions firsthand when they talked about things that didn’t work out as they should have. The symbolism of this is important. When a CEO sits down to talk to customers to find out what they think, it sends an important signal to the rest of the organization and the industry.

FIGURE 1.9

Gjensidige CEO Helge Leiro Baastad and 130 of his managers spend a day calling 1,000 random customers to hear what they really think about the company. (Courtesy of Gjensidige)

The results of these kinds of company-wide changes take time to surface. Two and a half years after starting this process, Gjensidige have seen a dramatic rise in their position on the Norwegian National Customer Satisfaction Barometer and have won the two biggest customer satisfaction awards. They have consistently beaten market expectations with their financial results and can prove that they provide their services more efficiently than their peers in Europe and the United States. Still, according to Baastad, the business case for customer orientation should not be seen in isolation. It is a natural part of the bigger story of developing a modern and efficient insurance company that brings real value to employees, shareholders, and customers.