CHAPTER 9

The Challenges Facing Service Design

Economic Challenges—Moving Businesses from Products to Services

Ecological Challenges—Service Design and Resources

Social Challenges—Service Design for Improving Society

Service Design for a Better World

The issues raised in the measurement of the triple bottom line touch upon the large, complicated problems that affect everyone. In a globalized world, people are dealing with financial, environmental, and social problems on a scale and a level of complexity never before experienced.

Technological shifts may be pushing designers to think about services, but these larger economic, environmental, and social trends are also pulling us toward challenges that are new to design. Change offers a new set of opportunities for designers to expand our remit, break out of the studio, and engage with meaningful work. Creating economically successful organizations through attention to customer and user experience as well as addressing the social and ecological challenges outlined in this chapter is the foundation that service designers need to build over the next decade.

In this chapter we look at these three challenging and intertwining areas and how designers can approach them as opportunities to work with businesses, communities, and government agencies to redesign their “operating systems.”

Economic Challenges—Moving Businesses from Products to Services

Measurement is critical to showing how our designs impact the classic service goals of customer retention, loyalty, and advocacy to enable organizations to invest more confidently in service design and in new service innovations. But it is also important to amplify the capability of service design by leveraging its ability to connect the economic to the social and ecological in order to make the case for long-term, sustainable (in every sense of the word) change.

Service design has a role to play in shifting economies away from valuing things to valuing benefits, because what is required for this shift is behavior change in two key audiences: organizations need to shift their offers, economics, and operations to orientate around providing access and convenience rather than products alone; and customers need to shift their purchasing decisions from ownership to access and convenience. For both, this means leaving behind a model that they know, trust, and rely on, and accepting something new and less familiar. This is a major challenge that requires vision and motivation.

Design has the capability to provide that vision and to motivate change by providing desirable alternatives to trusted norms. Service design is particularly well placed because it connects the business thinking of the service proposition with the actual creation of tangible touchpoints that people will use.

Hilti

A great example of what a shift to service looks like for a product business is construction tool manufacturer Hilti.1 Hilti makes power tools that it traditionally sold to foremen or construction managers who would own and maintain the tools on behalf of their companies and be responsible for making them available on projects as needed. This responsibility of ownership, logistics, and asset optimization was a burden to the construction companies and their employees. Hilti saw an opportunity to remove these irritations. As the manufacturer, they thoroughly understood the products and had the flexibility of a much larger inventory, so they were in a better position to manage the tool set assets.

Hilti conceived of a service model that offered their customers the tools they needed, where and when they needed them, properly maintained and quickly replaced if they failed. This seems like an obvious step to take, but it required Hilti to develop a whole new way of doing business. Instead of selling tools to foremen on job sites, they now had to sell service contracts to finance directors and then run a service business delivering tools to customers on demand. This required vision and motivation—in this case, motivation from both Hilti and their customers.

Service design is relevant here in two ways. First, we can create these visions through design approaches that understand customer needs and irritations and translate them into opportunities that we can visualize to make them tangible and desirable. Second, we can prototype and run pilots of these new concepts to prove that the service is desirable to customers by staging the service in ways that are real but do not require immediate wholesale change. We can mitigate the risk of change and also create motivation through designed experiences.

From an ecological perspective, Hilti can now do more with less use of natural resources because the service model reduces waste in the system by making material goods work harder for longer, with less downtime and fewer failures. Most important, Hilti are now incentivized to make their tools last as long as possible to gain maximum value from them throughout their life cycle rather than purely at the point of sale. The ecological benefits dovetail into the economic benefits—Hilti can make more money by manufacturing fewer tools, and Hilti’s customers have better access to tools while saving money on wasted ownership of tools they don’t need.

Ecological Challenges—Service Design and Resources

Since the Limits to Growth report was issued from the Club of Rome in 1972, awareness has been growing of the finite nature of global natural resources and the limit to the planet’s capacity to absorb man-made waste.2 The most well known and understood of these issues is climate change, with scientific consensus that greenhouse gas emissions are on track to cause significant changes to Earth’s climate and will impact humanity in the form of drought, floods, and crop failure. Our demand for finite natural resources is outstripping the speed with which they can be replenished, and their extraction is damaging ecosystems. We are all aware of the impact of deforestation on other species, but it also impacts humanity in places like Bangladesh and Pakistan, where cleared land no longer absorbs rainfall, leading to extreme flooding of low-lying villages, towns, and cities.

A complete catalogue of ecological challenges is beyond the scope of this book; however, we do want to explore the role design, and specifically service design, has in addressing these challenges.

Underlying most ecological issues is the industrial mode of operation and thinking. The industrial revolutions and resulting material wealth have been powered by fossil fuels—from coal to gas to oil—and have relied on readily available natural resources to feed human consumer societies. Notions of wealth and value are built on physical things—the wealth of nations is measured in terms of gross domestic product. Major corporations depend, in the main, on constantly selling more products. Consider the automotive industry as an example. In 2011 the number of cars in the world surpassed 1 billion, and yet the primary goal of auto manufacturers is to sell more cars. To do this they must open up new markets, which is clearly unsustainable, and yet it is the dominant economic model of success based on continuous, infinite growth on a planet that has finite resources.

The chink of light in this situation are the growing service economies and the trends in consumer demand away from ownership toward a better understanding of value and utility. Service design has a role to play in speeding the shift to a more resource-efficient economic model that uses service as a means to decouple value from resources. As individuals, we begin to look for the best form of mobility rather than desire to own a car; we sign up to subscription services, such as Netflix, rather than hoarding stacks of DVDs that we will never watch more than twice; and we share tools with our neighbors through services like Neighborgoods.net instead of leaving them idle in our toolbox (the average drill is used a total of 12 to 13 minutes during its lifetime). What we actually need is the experience or utility—to get from point A to point B, to watch a film, or to make a hole in the wall—not the product.

In these kinds of collaborative consumption and redistribution models, the personal value is in the convenience and access rather than burden of ownership, but the aggregate value is ecological (and, quite often social, because such services can help reconnect people within neighborhoods).3

For a service to replace a product, it must be tangible, useful, and desirable, and service design provides an approach to designing these services. Many solutions to ecological issues ask people to stop doing something without offering an alternative, but it is much easier to offer people an alternative than it is to ask them to give up something.

It is not that products disappear completely—most services are productservice systems that combine service and product elements—but the opportunity is to do more with less. An organization providing products as part of a service can make more money from a single car, DVD, or drill because that object is providing more value to more people. The service adds value over and above that of the original manufacturer of the product. Services that use networks to connect people act as multipliers to these individual shifts in resource usage and can reflect the effect of those multiplied changes back to people in ways that inspire further shifts in behavior.

Hafslund

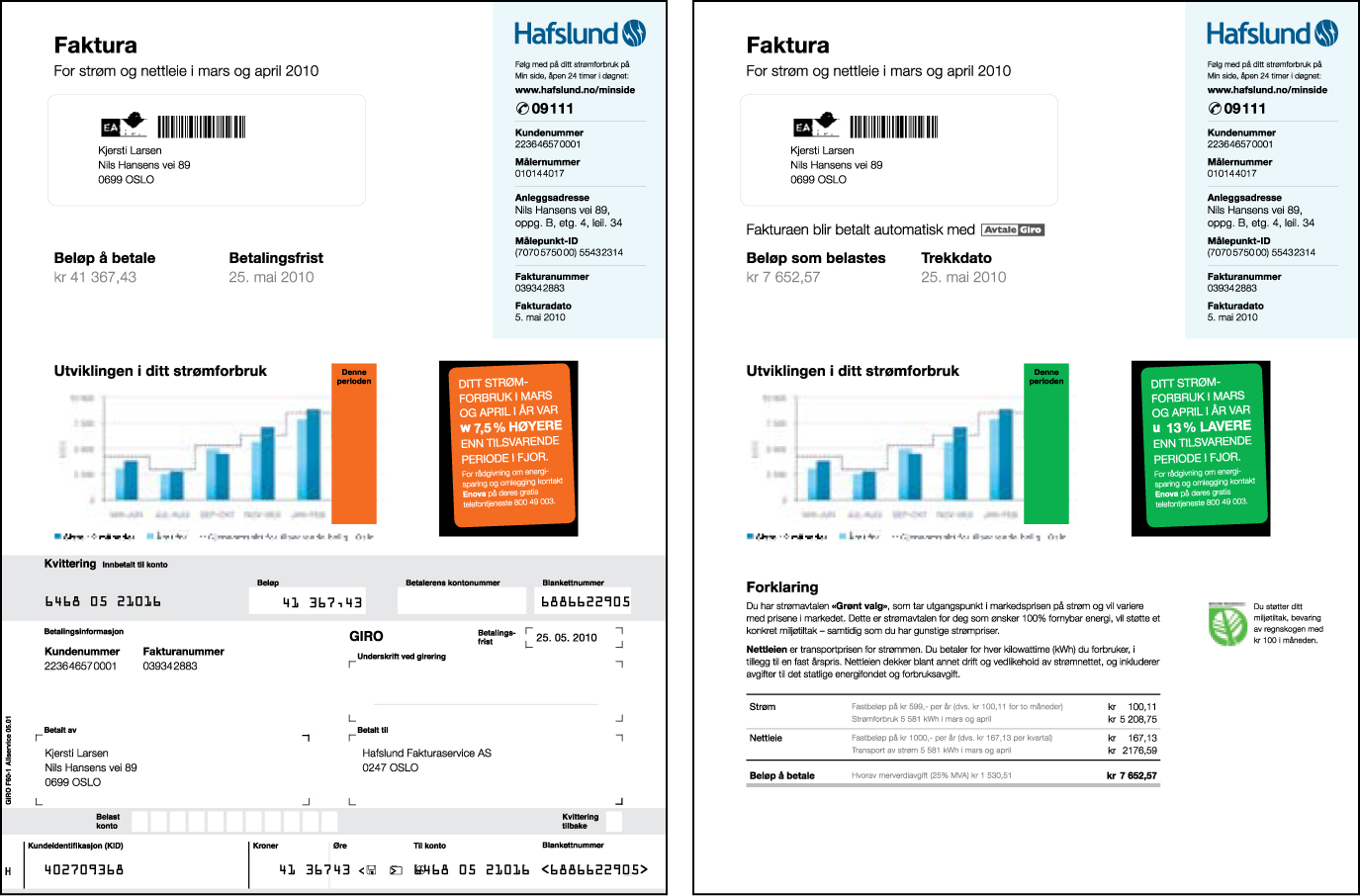

One example of a design change aimed at effecting behavioral change is the invoice redesign for Norway’s largest utilities provider, Hafslund. A lot of calls were being fielded in Hafslund’s call center from customers who did not understand their bills. The primary goal of the design work was to make the bill easier to understand, which would improve customer experience and loyalty and reduce call center traffic.

It was also an opportunity to use the invoice to nudge people toward reducing their energy consumption. A color-coded box added to the bill clearly indicated whether customers were using more or less energy than during the same period the year before. By incorporating the feature in the new invoice, Hafslund showed customers that they offered more of a service than just providing electricity through the wall socket and that they were concerned with more than just profits. Helping to develop collective responsibility for the environment is also part of their service (Figure 9.1).

FIGURE 9.1

The green box states, “Your electricity consumption in March and April this year is 13% lower than in the same period last year. Call this free number to get advice on how you can save energy.” The orange box indicates an increase in energy consumption.

In this case, triple bottom line thinking helped introduce new features that customers appreciated. Hafslund’s bill redesign saved them money because it reduced the number of calls to the call center, but the company’s choice to add value by providing customers with information to help them save energy has impacted the environment in a positive way. In the future, the aim is to measure whether Hafslund’s customers stay loyal to them and whether they are willing to pay a premium price for taking collective responsibility for the environment.

Social Challenges—Service Design for Improving Society

From the outset, our ambition as service designers was to work with public services. Initially, this was because we felt we should not ignore such a large segment of the market. As we have learned more about public services, we have teamed up with a number of other designers and design advocates who see a role for service design in addressing key issues that public services face. Although service designers are new to this space compared with the policy makers, social scientists, and economists who dominate public debate, it is precisely because we are not public service natives that we bring something different and valuable to the table as people try to rethink and change public services.

In the public services sphere, such as education, welfare, and healthcare, the legacy of industrial thinking shows just how far the production-line model has spread. The same industrial thinking that we have challenged as inadequate to the nature of services is also proving inadequate to address today’s social challenges.

There is growing recognition in developed countries that public services and the welfare state were established in a different time for different needs and that major social challenges, such as aging populations and the prevalence of chronic disease, mean that we will have to dramatically rethink these services. The very real concern is that services will become unaffordable and that they are not meeting the needs of the people they are meant to help. In the United Kingdom, public service innovation group Participle (www.participle.net) argues that the welfare state is in need of radical rethinking to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

For example, two pillars of public service in the United Kingdom are the National Health Service and the comprehensive school system. Both are fantastic efforts to bring healthcare and education to everyone. They address two of the “great evils”—disease and ignorance (the others being want, squalor, and idleness)—as defined by British social reformer William Beveridge in 1942.4 We now take for granted many of the achievements of these reforms in the same way that we take industrial products for granted—they, like the washing machine, have raised our standard of living and deserve our gratitude.

Yet, these monumental projects have an industrial mode of operation—the mass production of literacy or disease eradication. Hospitals and schools can seem like factories, and people’s experiences of these institutions can be impersonal. More important, these institutions may be reaching the limits of their capacity to deal with the issues they were created to resolve.

Taking the example of healthcare, we can see that although people no longer live in fear of many of the diseases that were still deadly in the 1940s, they are now faced with a number of chronic conditions (such as diabetes and hypertension) that are severely debilitating and cost a fortune to deal with. These already account for 75% of US healthcare costs.5 In simple terms, large high-tech hospitals are not the solution for these woes.

In the case of education, we have found through our own work with young people and employment services that, although schools are providing literacy for most students, some young people are not connecting with the school system and feel that they have wasted their time at school. They leave with few prospects and, in the worst cases, their confidence has been ruined by their inability to achieve in school. These young people need something from the school system that it is not capable of delivering.

In both of these cases the industrial model dominates. To be a patient in a hospital is to move from one processing station to another, like some kind of healthcare assembly line. The dominant management concept in hospitals is one of increasing efficiency and cost savings (particularly in the United Kingdom at the time of this writing). Patient healthcare is second in priority, despite government rhetoric, and the experience of patients receiving or medical staff providing that healthcare is trailing along in the distance.

Educational institutions suffer a similar problem. It is no coincidence that the spread of mass public education coincided with the Industrial Revolution. Families moved from rural areas to cities to work in factories. Children needed to be cared for while their parents worked, and they needed to be educated (although some children ended up working in factories, too). The style of this mass education matched the jobs the children were likely to get in the factories, requiring them to sit still, be quiet, do what they were told, and learn tasks by rote and routine. If you compare a classroom and its rows of desks with a sweatshop and its rows of sewing machines, the resemblance is not a coincidence.

Efficiency and cost savings are at odds with providing a positive educational experience for students. The metrics being used to measure success are usually only those that are easy to measure in numbers, which tends to be grade average in subjects that are suited to this kind of grading. As everyone knows, the school experience adds up to much more than this. Many subjects are about making connections and having discussions and experiences. Most people’s grades on their school exams fade into irrelevance over the years, but the shared experiences or wise, touching words from a teacher can stay with people for a lifetime. But because it is hard to pin a number on these experiences, they stay out of the metrics.

In higher education the industrial model is largely the same. New students are raw material that must be stamped into the shape of a particular profession. Accountants, doctors, lawyers, designers, and social workers all roll off the end of the production line with degrees—and debt—in hand.6

It is clear by now that politicians and policy makers are struggling to tackle the big challenges and changes described in this chapter, but it is important to emphasize that we are not saying that service designers are going to take over and solve everything as some kind of design superheroes. The issues that service design uncovers and the solutions that it offers involve significant change management on organizational as well as political and cultural levels, and it is important that we work with professionals in those areas, as well as policy makers and advisors, to make sure the change actually happens. These kinds of partnerships only work when there is a climate of professional humility on all sides.

A good example is the UK-based social innovation organization The Young Foundation (www.youngfoundation.org). The foundation’s team comprises researchers, ethnographers, policy experts, general practitioners, and former management consultants. The foundation has been using service design approaches to design a new social enterprise, Care 4 Care (http://care4care.org), which uses time-banking principles to support people in creating additional care capacity and enable older people to live better lives and stay longer in their homes.

The foundation has also worked with affordable housing provider Metropolitan (www.metropolitan.org.uk) to help design a befriending service, again to reach older people in their homes, and also with staff and users of the hostels run by People Can (www.peoplecan.org.uk) to help bring the experiences of service users into the design of the organization’s housing and support services around the United Kingdom.

Make It Work

Although the service design model of measuring across time and touchpoints is actually quite simple, it has proven to be useful in complex cases. One of these is a project to reduce unemployment carried out with the City of Sunderland in northeast England. The city found itself in a particularly challenging situation in which, out of 37,000 unemployed residents, only 5,000 were actively seeking employment. The journey from worklessness back to work needed to be redesigned.

In public service design and innovation, success cannot be measured by competitive advantage, but rather by the value it brings to society. This is hard to measure, particularly in the multifaceted network of a community. With Sunderland, however, we were able to first present a credible business case for investing in a service pilot and later measure the results of the pilot to argue for a large-scale deployment of new services.

Sunderland has suffered more than most from the decline of heavy industry in England. Affected by the loss of both the coal mining and shipbuilding industries, the city has some of the highest rates of unemployment in the United Kingdom. Many people have never worked and come from families who have not known reliable employment for generations.

This setting provided the context for our work with the City Council on the project in 2005, which was supported by One NE, the regional development agency. The brief was to redesign the journey to work for long-term unemployed people, especially those with complex reasons for their unemployment, such as bad health, substance addiction, or caring responsibilities. It was necessary to look at the whole journey and, specifically, to develop a solution that was primarily informed by end user needs.

Starting with Fieldwork

The research involved in-depth fieldwork with a small number of individuals within a specific area of Sunderland. Researchers from the service design team shadowed participants’ days to understand how they lived, focusing on the interactions they had with services such as healthcare, social services, employment offices, and voluntary groups. From this work it was possible to construct an ideal but realistic blueprint of what needed to be in place for these people to make their journey back to work. The journey is based on overcoming barriers and is informed by the insight that people are not able to think about work until their more pressing needs, such as health and housing, are under control.

The blueprint, based on user needs, was then used as a common structure for all the partners on the project to organize themselves around. Health teams were able to see how they contributed to employment by getting people well, while rehab programs could connect to employment resources to help their clients’ progress. All the services came together to support individuals in becoming self-sufficient.

The blueprint made clear improvements in the user experience of employment support services. It also helped managers focus their resources on where they were most effective. However, it was also necessary to demonstrate that the activity was cost effective overall and for each specific activity. We needed to show that the idea the blueprint modeled was financially viable.

The Case for Investment

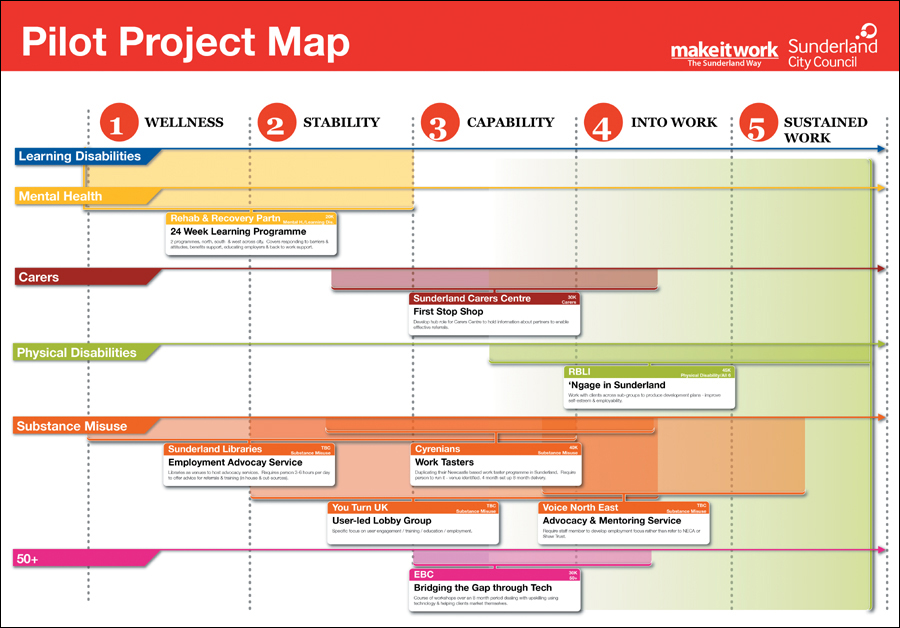

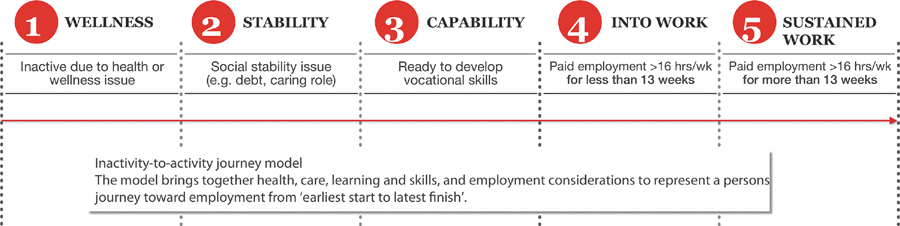

The business case for investment was based on the blueprint designed during this first phase of the project (Figure 9.2).

FIGURE 9.2

The five stages of getting back to employment provided the timeline for the Make It Work blueprint.

There is not a specific number for how much one unemployed person costs society, but we were able to find that the state spends between £10,000 and £40,000 per person out of work, per year, in benefits and other social costs. We knew the rates of worklessness in Sunderland, the services being offered along the customer journey, and what it would cost to redesign these services. We now had a metric for calculating the value of our design intervention.

We calculated that a reasonable goal would be that for every £1 invested, there would be a £2 savings to the public purse—a 100% return on investment. If scaled up, the benefits would be massive—100 people in work would create a minimum £1 million in savings per year. Remember, the city had 37,000 people out of work.

The City Council believed in the potential defined by this initial project, and the insights and concepts were shared in workshops with more than 200 operational council employees to enable them to improve their services.

Making It Work

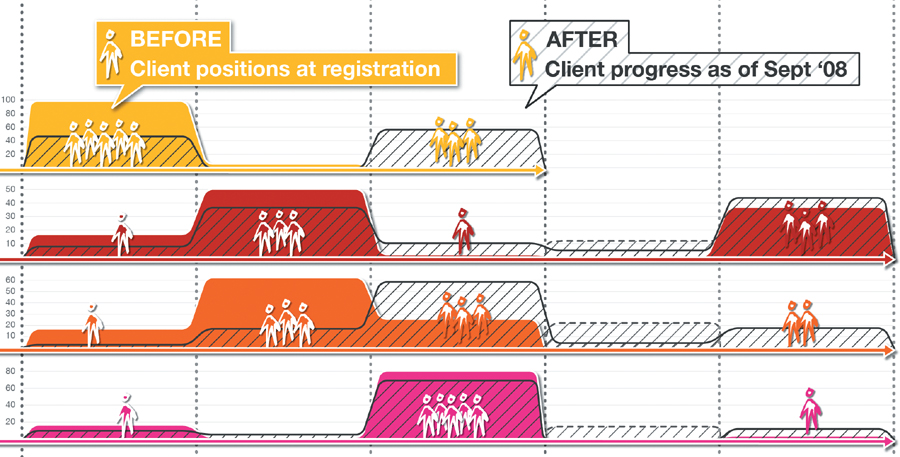

The blueprint made sense on paper and the service activity was aligned to a cost-benefit model, but it was important to demonstrate that it worked in practice. To do this, we needed to understand how all the different departments and organizations would work together, so we needed to go beyond small experience prototypes and design a pilot project that would apply the principles on a small scale but involve as many of the partners as possible (Figure 9.3). This way we could test the activities before taking the service to the whole city.

FIGURE 9.3

The pilot project map shows how a series of services were structured along the customer journey to provide different client groups with tailored offerings in a progression toward sustained work.

For the pilot, a number of complementary services—both from the public and voluntary sectors—were commissioned to work together to test the blueprint. All parties would use the journey to work as their model and collaborate to ensure that their clients had their needs met in the order outlined in the blueprint.

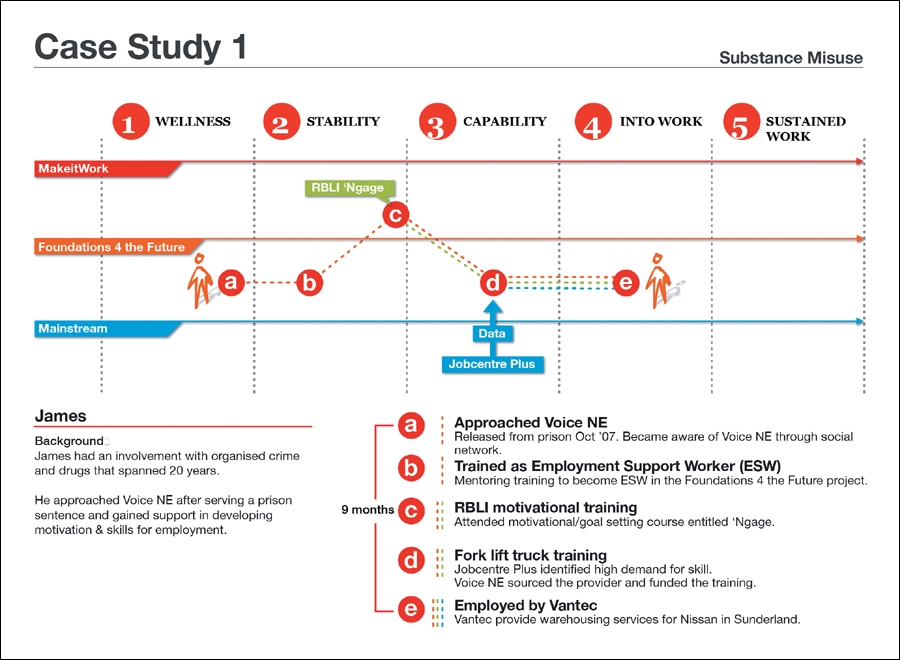

During the pilot, the knowledge that it takes time to help people into work became tangible. It became evident that, although some people would make it into work, others would only begin their journey, perhaps overcoming a major barrier but not finding a job. It was clear that there was value in this activity in the long term and also immediately within the funding term of the pilot, but this value needed to be demonstrated to the project sponsor. To do this, the costs and benefits were aligned with the service blueprint. It was then possible to uncover the savings to society of eliminating homelessness or addiction and apply them to individual cases. We also knew the cost per person of all of the partners in the pilot, so we were able to make a costbenefit calculation for each step of the journey (Figure 9.4).

FIGURE 9.4

in the case of individual clients, we tracked their journey through the system to see how they engaged with different service offerings on their path toward work. One of these was James, who after serving a prison sentence went on to work as a forklift truck driver for Nissan.

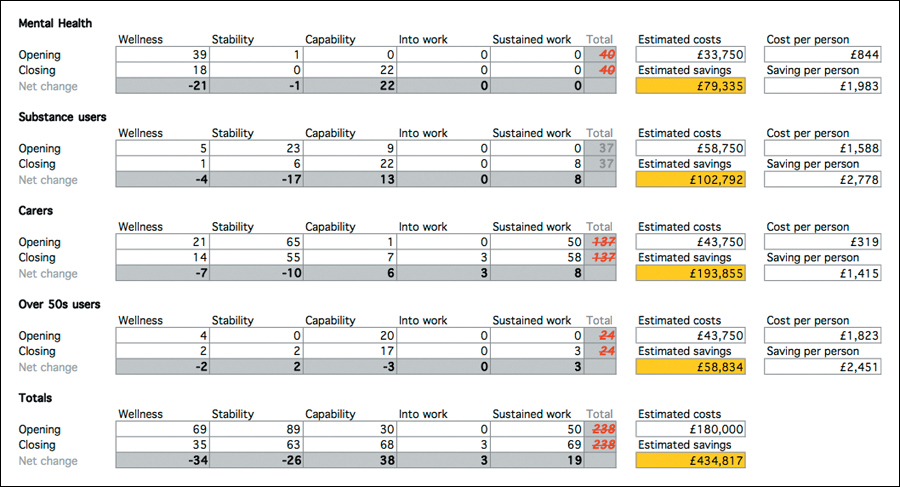

The Social and Economic Return on Investment

Over a period of nine months, a range of organizations in Sunderland partnered to pilot a series of service concepts with 238 workless “clients.” Of these, 19 people had come into sustained work during the pilot. Just as important, 38 people had gone from being unable to work to being capable of working, and 72 people in total had jobs safeguarded. The results showed that the redesigned services could bring huge benefits to the community (Figure 9.5).

FIGURE 9.5

The Make it Work pilot included people who were out of work for different reasons—from people suffering from mental health or substance abuse problems to people who took care of family members or were over 50 and did not fit into the local labor market. This chart shows how the people in the different groups progressed toward work during the nine months of the pilot.

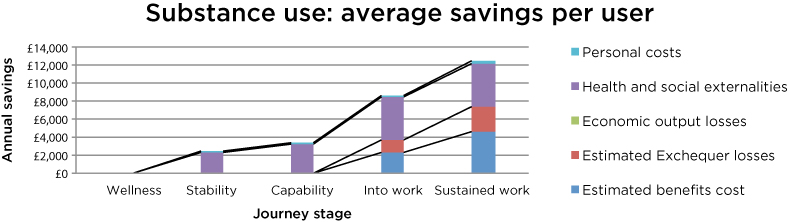

The Revenue Potential

After completion of the pilot, the data collected was used to estimate the costs and success rate of the design of the new services. To model the revenue potential, we broke down average savings for society per user into five well-documented categories. The model included economic costs such as:

- Estimated benefits costs—what the city no longer had to pay each individual in benefits

- Estimated exchequer losses/gains—the tax people pay when employed

- Economic output losses/gains—the value employed people create for their employers

- Health and social externalities—the value attached to improved health and reduced social problems

Personal cost impacts were also included in the model, even if they were hard to estimate and are not traditionally counted. The personal price of unemployment can range from social exclusion to excess mortality rates.

Savings for Every Step of the Journey

It is easy to assume that return on investment would only happen when people got permanent jobs, but this was not the whole picture. Using the business model, it was possible to demonstrate how Sunderland would be able to save money for every step clients took along the journey back to work, not just once they had reached their final goal of having a job.

For example, a person who manages to overcome mental health problems and progress toward work would save the community £4,000 simply by becoming capable of working. Savings would rise up to £20,000 if the same person managed to get into sustained work (Figure 9.6).

FIGURE 9.6

The rising savings to the city of a person moving through the stages of getting back into sustained employment.

Based on the pilot, we now had data on what the costs of service provision were along the customer journey, as well as for different target groups. We also had data on the success rate of the new service design and its estimated savings, and we could calculate return on investment for a full-scale launch of the new design.

The service pilot showed that for a cost of £180,000, the community had saved £435,000 (Figure 9.7). This gave concrete numbers for estimating a 140% return on investment for a full-scale launch.

FIGURE 9.7

The total cost savings of the Make it Work pilot project.

The Bottom Line

The Make It Work project demonstrates a highly complex case involving a broad set of stakeholders and a public service context where performance cannot simply be measured in profit. Using the framework of a service blueprint presented the opportunity to model a service-native business case and merge it with the design process. It illustrates the common ground possible for design, economics, and social policy.

Tackling Wicked Problems

Social challenges are wicked problems.7 These are complex, intertwined with many other problems, and probably not “solvable” in the way we are used to thinking about solving problems. In most developed countries, however, approaches to social challenges have two facets: they aim to address a defined goal, and they need to do it within limited means.

In a democracy, people aim to achieve the best possible level of agreement on these goals and the resources they deserve. For example, a teacher aims to help her class achieve a set level of literacy over the academic year, but must do this with the limited time and attention that she has for each individual in a class of 30 children. Class sizes are a factor of education budgets.

Applying service design to a social context means understanding these twin drivers and understanding the needs of all the stakeholders. Designers need to engage with the public policy world that defines goals in terms of social goods (literacy in our example) and also understand the resource limitations that the service works within.

A major challenge for services in a social context is that the defined goals, although hopefully democratically defined, can easily be disconnected from the goals of all the people involved both in service provision and as service beneficiaries. Service design offers a way to examine the fit between the two and recommend new ways to connect people that achieve goals and also reduce the demands placed on limited resources.

Socially beneficial services have a different relationship dynamic to commercial services. A commercial service that the customer pays for is a relatively straightforward relationship. To make a phone call, the customer pays by the minute for that call. The company’s goal is to sell as many calls as possible.

We need to understand that in a social context there is no customer. Not the students, the parents, or the teacher. This means that the driver of the service is often the government agency that set the policy goals that may or may not be aligned with the goals of the other people involved. Teachers may have different ideas about what value means in education; parents certainly want different things for their children; and the children themselves want something different from their school day. A service design approach to understanding people and relationships can uncover the disconnects between the goals and motivations of all the different actors.

Socially beneficial services have a wider social value to the health of society as well as being valuable to the individual. Services such as healthcare, education, and welfare insurance benefit the national well-being and economy. Police, prisons, and probation services are also, generally, seen as socially beneficial in terms of public safety, if not directly beneficial to some individuals. The relationships that the service consists of are different. Even if we are the direct customers of the service, the provider organization is not motivated to simply sell us more. They will often, in fact, wish to reduce our usage, or in healthcare parlance “discharge” us from the service.

In the case of some services from which we personally benefit, such as healthcare, we would ideally not be using the service at all; we would rather simply not be ill in the first place, and healthcare providers and insurers are happy if we stay healthy. If the service is prison, we clearly do not want to use it at all and may or may not benefit personally from its use in the long term. Ideally, of course, prison would actually benefit and not just punish those imprisoned there, which in turn would benefit society. Sometimes this happens, but all too rarely.

Where do motivations and interests lie? In some instances, such as health-care, we may have a huge personal interest in the success of the service (our own life chances). In others, the benefit may be one that we are not personally convinced is in our interest, but may be of benefit to society (taxation is a good example of this). In other services, the benefit can be too distant for the service user to grasp at the time, such as the benefits of education to a young child.

The opportunity for service design is to use insights research to understand the nature of the relationships and identify the motivations of the people involved, to define opportunities for new ways for the different parties to achieve their goals. The service design toolkit contains some invaluable approaches that can be used to rethink public services. These can help designers move from an industrial way of thinking about these issues and help deal with the complexity and multiple stakeholders that are inherent in services.

Service Design for a Better World

In the United Kingdom, companies like Participle (www.participle.net), which work with and for the public to develop new kinds of public services, and organizations like Demos (www.demos.co.uk) and The New Economics Foundation (www.neweconomics.org), think tanks that focus on politics and economics respectively, are working hard to unpick and rethink these complex social problems.

On a global level, service design approaches are being used more and more often in areas such as peace, security, and development within organizations such as The Policy Lab (www.thepolicylab.org) and The United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (http://unidir.org). These organizations are working at the highest levels of development and security policy, examining life-and-death scenarios in some of the most dangerous countries in the world. There is a recognition that the old “best practice” way of approaching this kind of work no longer suffices, but that a shift toward a “best process,” which design can contribute to, is a possible way to rethink international intervention in these countries. At the same time, these peace, security, and development professionals caution designers to be more rigorous about the cases they put forward because the outcomes are at a very different level. A poorly designed website might mean a frustrating purchasing experience, but a poorly designed development or disarmament project might mean the death of many people.

Service design is also being employed in bottom-of-the-pyramid social entrepreneurship projects.8 Bottom-of-the-pyramid projects target the 5 billion people who live on less than $2.50 per day—those at the bottom of the economic pyramid—but who, collectively, have enormous buying power. These projects are not aid projects, but sustainable business models that deliberately target this extremely low-income demographic to provide them with products and services to improve their lives. The results of these projects are measured in terms of social change as well as business success—both are crucial for sustainable, long-term change.

Companies like Reboot (http://thereboot.org) in New York are using service design methods, combined with traditional development methods, to help rethink governance and international development projects. Service design offers the connection of field research into the lives, needs, and behaviors of people on the ground to the design, development, and implementation of these business and services. It offers a bottom-up perspective and process to policies that have been traditionally implemented from above and afar (some aid agency managers are tasked with sending millions of dollars to countries they have never even visited).

Service design excels at dealing with complexity, breaking it down into its composite parts while still understanding the whole. Many other disciplines do this in other areas, of course, but services and the exchange of service value are central to our lives and the complex social, ecological, and economic problems we face, and we need a services mindset to tackle them. Crucially, service design provides not only a different way of just thinking about these problems, but the tools and methods to tackle them through design, implementation, and measurement.

The industrial model has served a small percentage of humanity well for the last 150 years, but it has unleashed a host of other problems that we now must face. Clearly, service design is not a panacea. Its future is in collaboration within multidisciplinary teams and with multiple stakeholders, as the examples in this book and from the organizations mentioned above demonstrate. As much as it is important for service designers to have an understanding of the economics and management concerns of business, the complexities of climate change, or the history of international development, it is perhaps more important to learn to work closely with experts in these areas. Service design is a powerful addition to the range of approaches that we need to design a better, more inclusive, and thoughtful future.