Value Creation Drives Service Innovation

Remember, in the future, the brand is owned by the consumer, not by the company.

—Martin Lindström

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence then, is not a single act, but a habit.

—Aristotle

This chapter focuses on the importance of understanding “value in use”— the value-creation process of the customer’s. Questionnaires, focus groups, and even in-depth interviews rely on a customer’s memory of this process. Research shows, however, that people are not very good at remembering such activities in detail. Organizations must therefore utilize user research methods that uncover needs and be customer-oriented in order to meet those needs.

Preview of Action Questions

Action questions for the innovator reading this chapter include:

Who in your organization observes users creating value with your services?

How is user knowledge (1) saved and (2) put to work?

Is your organization truly customer oriented?

Understanding the Customer’s Value-Creation Processes

As discussed in the previous chapters, value is created through the use of products or services. The process can be very context or situation specific. For most coffee drinkers, the value of coffee is greater in the morning than at night and the first cup of the day is the most valuable. In order to understand the real value to a customer, it is necessary to understand how, why, and in what context a service is used. A service can be perceived incorrectly if we fail to take into account the context.

Comparing the development of digital cameras with built-in cameras in mobile phones helps us understand how the perception of value is dependent on context. Advanced system cameras still take significantly better pictures than a mobile phone. However, mobile phone cameras provide acceptable quality and are at hand for photo-worthy moments, while a camera is too often lying at home in a drawer. The golden moments, such as a child taking its first steps, are thus more likely to be captured on a mobile phone. Cameras have enjoyed spectacular technical development, but since their use is limited to photography and requires planning and configuration, they are often not at hand when a moment worth photographing occurs. Thus, nonprofessional photographers take more, and more valuable, photos with mobile phone cameras than they do with technically advanced digital system cameras.

Once again, an exclusive focus on the product or technical solution is insufficient. Offering a fabulous direct or indirect service is not enough— companies must also understand the full context of the customers’ value-creation processes. The study of fast-food milk shakes discussed in Chapter 2 illustrates the importance of context. A relatively simply product was used for very different purposes in the morning and in the evening. In the morning, commuters used milk shakes to make a boring commute more interesting and pleasurable; in the evening, parents used them to reward or bribe their children. The difference in value creation or jobs performed by the simple product led to the conclusion that thicker milk shakes would enhance the experience of morning users, while thinner ones would improve value creation in the evening!

The interaction between the customer and company during customer value creation is important. For instance, when a bank clerk gives advice, the value of the advice is not only based on the customer’s financial situation, but also on how well the customer is able to answer questions and, in turn, how adept the clerk is at understanding the customer’s situation and asking the right questions. The customer and the bank interact jointly to create value for the customer. The customer’s situation and interaction with the service supplier have proven very difficult to understand.

It is difficult to guess in advance what kind of value-creating processes the customer prefers. In addition, the value of the customer’s own efforts (the interaction) is too often forgotten by the company. The customer should not be viewed as a passive participant—someone who is served. Let us use an example from the electronics industry by analyzing a company advertisement (see Figure 3.1).

The product details of the TV in Figure 3.1 give the impression that the components’ technical specifications are solely responsible for the value-creating process. Value is generated by the TV and the customer only needs to passively view it. The technical solutions found in the advertisement—described in the form of abbreviations and trademarked terms—are apportioned a large amount of space, and, as a consequence, very few words are dedicated to explaining the experiences a customer is expected to enjoy by using this particular TV. How “S Recommendation” is valuable to the customer is uncertain. “Sell the benefits, not the features” is a well-known sales slogan, but some firms still talk about technical specifications and believe they will do the job without considering the cocreation of the customer. Service innovators might update the slogan to “Sell the value, not the features.”

Figure 3.1 Product details from an electronics store

Fancy acronyms or technical jargon do not generate value. If the customer wishes to increase family bonds by watching TV in the living room, the choice of TV program may have a significantly greater impact than the technical attributes of the TV. The customer’s ability to use the features, for instance, by connecting the TV to other devices, impacts value creation. A 40-in. TV may appear diminutive in a very large room, but could be too big for a small student flat. The context and interaction determine the value and the technical features are just tools that might influence value creation.

Value-Creating Processes Are Difficult to Capture

Research literature often describes customers’ value-creating processes as hard to capture or “sticky.” In addition to being context specific and subjective, the information is only interpretable and understandable by the person experiencing the value, making it difficult to transfer, hence being “sticky.” The fact that information is difficult to interpret without the customer stresses the importance of including customers or users in the development process. Stickiness can be rooted in the fact that the information is largely based on what users take for granted; consequently, there is no guarantee that users will be able to recall said information in a survey, focus group, or an in-depth interview. User research is often conducted in an antithetical context (often at a company) and point in time compared to the real context in which value is created. A successful interview depends on asking the interviewees perceptive questions that encompass the value experienced by a customer and the customer’s ability to provide rich, detailed answers. The answers must then be interpreted by the interviewer or a research team in such a way that they can be transformed into information useful to the company at a later stage.

Interview methodology and concomitant focus groups are based on a passive view of customers. If a service offering is totally new, usage is difficult to imagine—possibly unthinkable in advance. Customers can only respond to what they have experienced, for example, existing services. Too often user research seems to assume that as long as the customers are asked the right questions, they will give the “right answer.”

A more active view of customers regards them as coproducers or cocreators of value. Their more active role generates more understanding and ideas than from answering predefined (and often incorrectly posed) questions. A contributing factor to why new company offerings sometimes fail is that companies have more knowledge of their own offerings than of the customers’ needs for the solution contained in the service or product. This might result in a new technical solution, as in Table 3.1, built on technology that the customer does not understand and perhaps has no use of. Companies and organizations do indeed have employees with great solution development skills; yet very few know how to analyze and appreciate the customers’ needs.

Our studies show that companies should continue to communicate with customers during the development process in order to understand how a solution may be used to meet the customers’ needs, as knowledge of their situations and interactions is best acquired through long-term communication.

The aforementioned context gives rise to the concept market-driven service innovation or outside-in perspective, which is based on a deeper understanding of the customers’ cocreative efforts and contexts. The innovations also utilize the fact that many customers appreciate being actively involved in contributing to a service or physical product so that it better matches their needs. For clarity we want to stress that this does not exclusively involve explicit needs, but also implicit and perhaps even as-yet undiscovered, so-called latent, needs. The latter can be difficult to articulate and predict. The methods for discovering and verifying those types of needs often involve staying close to customer markets, interactions, or communications. The customers’ value-creating processes are not best analyzed in a clinical office environment—rather, the company must be proactive and interact with customers in the environment where they actually use the services. In addition to immersing themselves in customer information, companies essentially need methods that follow the customers in their own context—or location—in order to understand how they think.

We contrast market-driven service innovations to innovation that stems from a “laboratory” or internal development process. We want to emphasize the importance that company staff personally get to know their customers and contexts via personal experiences, and to only use intermediary actors as complementary tools. We will also illustrate how a company should try to involve customers in development processes in order to gain access to their experience and competence. We also want to stress that this curiosity about the customer has to be built into a company’s culture—a company needs to realize that customers do have good ideas.

Customers Have Good Ideas!

Innovation is all about matching a solution to a need. Historically, those in possession of the solutions are companies that are supposed to chase information about user needs. However, there are numerous examples of customers finding good solutions to problems or needs themselves. Many of the products we use on a daily basis originate from customer ideas—everything from chips, coffee filters, and chocolate chip cookies to Frisbees, rollerblades, and computer operating systems. Our research has shown that, given the right circumstances, customers are capable of developing ideas that are both more creative and of higher user value than ideas originating from company product developers.1 This is not that strange since users are more aware of their own needs and often have ideas on how to meet them. The challenge for a company to involve customers as developers is to provide the customers with the tools needed to successfully innovate service.

Companies often use highly educated engineers, expert in the underlying technology, to find new solutions and products. This can be a source of development problems. Consider a service solution designed for teenagers. Most company developers would have a completely different set of values, behavioral patterns, income sources, and priorities than teenagers, making it very difficult to understand what the target customers want and are willing to pay for. This could be an excellent opportunity for the target group—the teenagers—to become innovators as they possess the knowledge of elusive (hard-to-capture) needs, namely their own experiences and value-creating processes.

An additional reason why customers are sometimes better equipped for creative success in innovation than companies is their less restricted thought patterns. Customers are simply not aware of how the current solution works, the limits on the current technology used, what has been the company tradition, or how the competition might respond, making it easier to think freely.

Take text messages (short messaging service or “SMS”) as an example—the Finnish engineer Matti Makkonen has described how he and two of his colleagues brainstormed the SMS into existence over a few beers and a pizza in 1984.2 It took 10 years, however, until the first text message was sent, and even then, no one imagined it would amount to anything more than a way for businessmen trying to reach each other in the absence of other forms of communication! Makkonen et al. thought that they had invented a service exclusively for businessmen.

The operators hesitated to charge for sending an SMS since they judged the market to be small but the newly developed service could be a good differentiator for the operator. The rest is history, as individual users became the services’ most fervent users. Texting was an excellent source of income for mobile operators for many years. SMS was not the result of a meticulously planned process; it illustrates the difficulty involved in predicting innovation success. Customers need to be involved from the start of an innovation process to enable an understanding of value-generating processes.

It is not always easy for the customers to provide comprehensive information on how they act, think, or live. “Sticky” information is so obvious to customers and users that they cannot correctly describe it from memory without forgetting important details. Think of how you would give directions to your home—you would probably forget some important details because you would most likely take it for granted. Alternatively, try explaining to a teenager how they should think and act when driving a car—it is extremely difficult! The reason for this is that we establish automated routines or mental shortcuts in our brains (heuristics). If this process of automation never took place, every routine activity would be far too resource intensive for our brains, which would not be sustainable in the long term. However, the use of mental shortcuts also makes it more difficult to explain our routine actions to any external party. It is also expensive and time consuming for companies to acquire and understand this type of information. Therefore it may be best to involve the customers in the development of new service directly.

Research results generally show that companies are not adept at using the customer to improve or create innovative solutions for their products. Many companies understand the benefit of using customer information, and are even willing to open up the organization and invite the customer in; yet very few are skilled at really utilizing customer information during the development of new services. The culprit is, again, routine behavior—not having performed a procedure previously makes it difficult to implement constructively on a bigger scale.

In our estimation, most companies have a bias to solutions developed internally. Many have a proud and strong tradition of implementing inward–outward innovations, preferably in laboratory settings, which leads to a potential lack of aptitude for listening to, or analyzing, customers and their value-creating processes. Companies are often solution oriented and possess a profound technical understanding. These companies’ main weakness lies in the choice of working according to an outward–inward paradigm. Our research studies indicate that companies rely excessively on consultants for understanding users, and organizational knowledge of how to gather customer knowledge is often lacking. This is unacceptable: Companies have to acquire their own competence and understand their customers; customer understanding must be considered a core competency. Yet, several studies show that even when companies conduct customer surveys, interviews, or focus groups, the results are not necessarily ever used or distributed within the organizations.

The Right Method at the Right Time

Our research uncovers a pervasive lack of company knowledge of the applicability of user research methods in service innovation development.3 Many companies are not aware of the strengths and weaknesses of different market research tools. Consider a toolbox: In the same way hammers and screwdrivers are useful for a certain set of tasks and useless for others, focus groups or ethnographical studies are useful for certain types of information acquisition. Table 3.1 contains a classification of some of the most common research tools available. Please note that Table 3.1 is not a comprehensive list of research methods but an overview.

As shown in Table 3.1, the prevailing customer information strategy in companies is based on using information stored internally in the organization. This information may consist of customer complaints, warranty claims for previous products, or information from salespersons. Using only this type of information in the development process may lead to minor improvements of existing products, but may also lead an organization to miss key opportunities. In addition, customer information is reformulated and reinterpreted—from salespersons to marketers to developers—in a multistage process that will likely simplify or distort it. Moreover, this specific type of information is not centrally compiled for use during development. Table 3.1 indicates that this type of information is appropriate when the company is improving existing services and that it may also be regarded as a gold mine for preventive actions. In particular, it is possible to find problems that have previously been overlooked or minimized.

Customer surveys are often carried out with traditional methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups and surveys, and often marketed as miracle tools capable of revealing every possible customer secret. Focus groups and questionnaires, in particular, have enjoyed considerable popularity. Focus groups are based on gathering at least six customers (not more than 12) to carrying out structured group discussions in a particular area of focus. However, focus groups may be useful if wanting to acquire large amounts of data at a relatively low cost. Another advantage is that it taps into the human ability to stimulate interparty discussions. The negative aspect though is the relatively small amount of discussion time allotted to each individual and that the discussion can easily be taken over by anyone with strong views. Imagine a focus group of eight people. The average group will convene for approximately two hours. Evenly distributing the discussion time leaves 15 minutes per person. Since every person’s contribution to the discussion will be fragmented, it is quite obvious that this method will not paint a particularly clear picture of an individual customer.

Table 3.1 Research methods used in a service innovation process

Service improvement |

Incremental service innovations |

Radical service innovations |

|

Focus |

Reactive |

Reactive |

Proactive |

Methods |

Complaints Critical events Observations |

Focus groups In-depth interviews Questionnaires |

Lead user methods Customer involvement Ethnographical studies |

Comments |

This method category is based on existing information or information on typical problems experienced by the customer |

This method category is based on how companies should consolidate their existing strengths and involves what customers have experiences after the fact |

This method category captures information in the customers’ own context and is based on their actions, often in real time |

Furthermore, group dynamics limit the creativity and quality of new service ideas generated through group brainstorming and focus groups. A recent review of 50 years of empirical evidence on generating ideas from these group methods shows that individual interviews or even individual brainstorming produce (1) more ideas for innovation, (2) higher quality ideas, and (3) more radical ideas than group methods, even when the total time per participant is equal.4

In-depth interviews have the advantage of providing a more complete picture of the customers’ views, but time consumption and difficulty carrying them out practically are obvious disadvantages. In-depth interviews and focus groups too rarely take place in the customer’s own locale or context and customers are instead expected to recall information during the interview. Questionnaires are used to test new hypotheses, but only reflect information contained in questions compiled by the interviewer beforehand. What is never asked will never be answered, and there is a risk the questioner is not aware of areas relevant to the customer’s value creation.

The aforementioned methods may be categorized as reactive and are suitable when customers are supposed to react to what already exists, that is, a service the customers have experienced or a situation they have found themselves in with some degree of continuity. The customers answer the questions based on what they recall or think they recall from past experiences. Some things are, however, unimaginable in advance and it is very difficult to react to something that has not been previously experienced; hence, many customers often resort to their best guess. Many are the companies that have acted on information that indicate a need for a particular solution, only to have the customers turn their backs on them after developing and offering what they purportedly wanted!

A chapter on user research for product innovation in the PDMA Handbook of New Product Development cited sticky information in the story of a small team developing the first Internet-based system for settlement of exchange traded derivatives held by financial institutions.5 A client referred to as “Alice” had been extremely cooperative with the development team. She had shared her frustrations with her current vendor, who was the market leader, and had given the team a detailed view of how that competitor’s service worked.

One day Alice and the development team were finishing breakfast when a marketing person asked her what one additional feature they could incorporate to make her life easier. When she gave an “incremental” answer—make settlement a little cheaper—a programmer on the team asked if the team could return with her to her office and watch how she started her day. It turned out that Alice spent a full half of her day (1) printing out settlement statements from her vendors; (2) entering the printed data into three different in-house programs for accounting, settlement, and risk analysis; and (3) error checking her reports for any input problems. With less than one day’s effort the programmer was able to implement straight-through processing, so that the data from the new service were automatically entered into the firm’s three programs before Alice even came to work in the morning—reducing errors and eliminating nearly four hours of boring repetitious work each day!

Why had Alice not suggested help with the input procedure? Remember that she was extremely open and supportive of the new service. She was unable to suggest automatic straight-through processing because she did not know it was possible. Without the office visit the development team would not have included a feature in the first version of the service that made it very competitive with the market leaders.

Henry Ford understood the issue of customers not understanding the possibilities: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Ford did not listen to the customers, which allowed his company to take the market leading spot in the United States. However, GM later overtook Ford using a customer-oriented strategy with the motto “a car for every purse and purpose,”6 developing products for each distinct market segment. This illustrates a distinction between radical and incremental innovations. Ford was alone in the beginning and created something new. Asking customers would not have led to an expressed need for a car; thus, they had to work in a more proactive manner. Henry Ford most likely realized the importance of personal transport by observing and understanding his contemporary environment. GM could later take advantage when the car had become an established product in society, and enabled further development, albeit via incremental methods.

The last category of methods in Table 3.1 is what we may call proactive methods—methods involving understanding the customers’ actions carried out in their own context. These methods are more forward thinking and better served for more innovative or radical service innovations based on ideas submitted by customers. The lead user method attempts to find solutions that may have already been developed by customers. The previously mentioned examples—coffee filter, chocolate chip cookies, Frisbees, and so on—are all solutions developed by customers. One closely related method is enhanced customer involvement by giving users access to tools to modify the companies’ services or products during their use. This effectively provides customers a platform on which they can test ideas with the purpose of encouraging the development of solutions they may find useful.

In-depth interviews and observation conducted at a user site advocated as “Voice of the Customer” research are an improvement on surveys or group methods for user insights and innovation ideas.7 Ethnographic studies go further in pursuing a deep understanding of needs and uses. An ethnographic study will systematically map user behavior and identify routine behaviors users and customers employ in different situations. New concepts are then developed from these studies to support the customers’ regular behavior and to enforce whatever the companies want to achieve in specific situations. Ethnographic studies have been used to design airplane gates to create more orderly aircraft boarding and the counters at McDonald’s have been studied to provide a better customer experience. (The lead user method, customer involvement, and ethnographical studies are further described in Chapter 5.) Let us exemplify the overall complexity of the aforementioned by quoting Toyota’s chief designer Kevin Hunter:

People can’t tell you what they want in the future, but they know what they want now. You have to balance creativity with market acceptability. You have to push the envelope and be progressive, but you can’t get too far out there, because customers won’t understand. Your design has to evoke something familiar or emotional while at the same time offering something new and unfamiliar. You have to avoid a strict design bias and remember who you’re designing for. You can’t be selfish, you must focus outward, and on the problem you’re trying to solve for customers.8

Multiple case studies have shown a positive impact from proactive user research tools on product innovation. A 2007 study of innovation in financial services at 211 banks examined proactive and traditional market research tools as constructs that defined the type of user knowledge driving service innovation. Each construct had six items. “Proactive Methods” comprised ethnography, user testing, site visits, lead user methods, in-depth onsite interviews, and voice of the customer (interviews and observation stressing context). “Tradition methods” comprised focus groups, group brainstorming, trade-off analysis, web surveys, test marketing, and concept testing. The study found that both the proactive and traditional user research constructs were antecedents of service innovation success, but the use of proactive methods had more effect on the success of more innovative and radical service innovation.

Building Your Own Market Competence!

We started this chapter asking who in your organization collects customer knowledge and what your organization does with the knowledge. When we ask these questions the answers are often vague; it seems that companies often rely either on intuition or market research from consultants who interpret the customers’ needs and the information for them. We believe that it is important for organizations to develop competency and be involved in user research. Is customer information not the most important data for a company?

Why is in-house customer knowledge so important? Hiring market survey consultants will convey their interpretation of the customers’ views and needs. Customer information is often extensive; so consultants filter and edit information to be manageable, without having full knowledge of the company’s industry segment. The company never has full knowledge of the customer.

In theoretical terms, the development of a service can be viewed as a matching process: The company should be able to develop a solution that corresponds to deep customer needs. The matching is carried out in a constantly evolving environment because of the constantly evolving customer needs, market activity, and technology. How well companies handle this matching depends on how well they can interpret explicit, tactic, and contextual user needs and deliver value to the customer.

Successfully managing this process requires relevant information and knowledge. We encourage questioning the role of external parties during this matching; it is important that the evaluators of customer information themselves have deep knowledge of the organization and its customers. Without a deep understanding, the distortion of information in this multistage process can be similar to outcomes in the familiar children’s game “Chinese whispers” or “Telephone.” Lack of insight into how the results have been acquired or how they should be interpreted causes problems, even in the early stages of collecting and sorting information. Don’t outsource customer awareness.

Having company employees gather customer information themselves will automatically give the data collected a higher priority than if it has been purchased from an external source. Even the article cited earlier about the ineffectiveness of group research does note that one advantage of the group processes is that all the participants believe in the results. Spreading information and ensuring other employees are aware of it become a part of daily operations if employees are involved in conducting the research. The most common obstacle for companies aiming to become more customer oriented is not difficulties in acquiring information and understanding what customers want, but, rather, using it during the development process. Thus, implementing customer information is more difficult than acquiring; so third-party research can be wasteful in many ways.

One additional warning: Some market survey consultants apply existing solutions to corporate problems by developing one type of research method and a relatively standardized process or survey to apply to everyone. Some agencies specialize in customer surveys; others in so-called mystery shopping; and others in focus groups. Agencies improve their business efficiency by scaling up their solutions. This endangers the whole idea of service innovation, namely to cultivate knowledge about customers’ value-creating processes. As a company, being aware of these phenomena and outlining the right requirements entails cultivating in-house competence at least sufficiently to manage agencies and consultants effectively. Having companies establish adequate levels of user research skills forces consultants to improve what they offer. This should actually be a mutually beneficial development. In studies of innovation success, knowledge of customer needs often appears as the single most critical component when launching new services.

We wish to point out that we have met many extremely driven and talented consultants in user research (and have done some consulting ourselves!) and we are not questioning the competence of all consultants— we simply feel that customer knowledge has to be regarded as a key competence for all companies. If a company does not know what its customers want, how is it going to deliver it to them?

Customer Orientation

Customer orientation can be described as a recurring process in which an organization (1) gathers customer information, (2) distributes the information, and (3) implements changes in existing products and services.9 It is crucial to prepare the organization for responding to customer information and for translating customer needs into business activities. This consists of ensuring that work procedures and methods capable of handling the customers’ needs are in place. Some kind of infrastructure is also needed in order for customer orientation to have an impact on daily operations, in the form of forums where the customers’ needs and experiences may be discussed; resources required to implement changes; or improvement groups.

A company’s customer-oriented service activities are characterized by the behavior of its coworkers. A company may have a customer-oriented strategy, but failing to support with the proper analytical work procedures, decision making, and implementation based on customer information will prevent the strategy from being more than well-written documents. Companies often understand the importance of working toward customer satisfaction, yet lack the requisite work procedures for carrying out the said work practically. An organization that fails to distribute and implement this increased knowledge of the customers’ needs and expectations will forfeit the impact it would otherwise have on daily operations, resulting in a customer-oriented organization only by name and not by action.

One of the primary goals of genuinely customer-oriented companies is good customer experiences and refined methods for gathering and analyzing customer information used in daily operations. One important question for companies to ask is to what extent such user research and action actually occurs and, consequently, to what extent they operate as genuinely customer-oriented companies.

Breaking Habitual Patterns

It is difficult for a company to become more customer orientated; old habits are hard to break. Carrying out tasks in a new way consumes more time and there is no guarantee that the results will be satisfactory on the initial try.

A research study performed by John Ettlie and Michael Johnson showed that when a new customer-orientation method was introduced, the organization actually became less customer oriented the first time the method was used. This phenomenon was explained by the organization focusing on the method itself and not on its purpose, which is to understand the customers’ needs.10 It should also be mentioned that there is no guarantee that an organization will be able to correctly identify existing work procedures and routines. External competencies, such as consultants assisting in customer-orientation assessments, could be useful in that case. (See we have nothing against consultants!)

An example can be found in a difficult period for Volvo Cars. In the beginning of the 90s, Volvo was in dire straits. Despite continuously improving cars, it fell further down the rankings in JD Power’s surveys on customer opinions of car makes. JD Power carries out one of the car industry’s most important global surveys and measures customer opinions of all makes available on the American market. The reason for Volvo’s drop in the rankings was its excessive focus on internal processes—improving productivity—which failed to include customers and competitors in the product and process improvements. Quality-improvement procedures were purely internally focused.

Volvo adopted externally focused quality-improvement procedures to restore balance in the company. A new strategy with increased customer satisfaction as the primary goal was deployed, leading to a change in work procedures. Volvo started carrying out more customer research, made customer information available to everyone in the organization, and began communicating customer needs internally, even including dealerships in the process. Within a few years, Volvo reaped the benefits in the form of higher customer satisfaction and increased revenue. In conclusion, Volvo managed to change its behavior, but a crisis was needed to break a habitual pattern.

The difficulty in breaking habitual patterns also appears in research studies. One oft-referenced study showed significantly improved products and financial results of an IT company that implemented work procedures to promote increased use of customer opinions. However, despite this evidence, that company chose to return to the old and familiar work procedures because the new methods required too great an effort to achieve a permanent change! The staff did not feel confident in working with the new procedures and simply preferred the old ones.

In our work with companies, we have often encountered people claiming “that’s how we’ve always done it,” “we’ve never done that,” or “that probably works there, but not here—we really are unique.” The pejorative term Not Invented Here (“NIH”), a suspicion of external ideas, is another force reinforcing inertia in an organization. It is simply not as stimulating to work with an idea that has been conceived by someone else, which is why external ideas and information are often rejected. Research shows that the NIH syndrome may potentially lead to innovations with low customer value and a tendency to reinvent the wheel. The expression “proudly found elsewhere” has been created as a counter movement to the NIH syndrome.

Customer-Oriented Companies of the Future

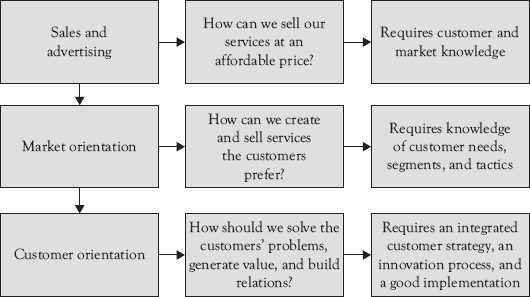

A true customer orientation is a competitive advantage for a firm. But are most organizations ready for customer orientation? Different types of specializations in organization operations in terms of their stance on customer information are available in Figure 3.2.

Companies used to do well by offering only one good product as long as there was a market for it. Companies have basically relied on finding market channels and marketing the product at the right price. The so-called market mix in accordance with the 4P model has, as such, helped companies to offer their product on the right market at the right price, represented by the top row in Figure 3.2.

Global competition has changed the situation however—one good product is not sufficient to survive, forcing organizations to become more market oriented. Market orientation requires companies to learn more about markets and customers in order to adapt their actions accordingly. This creates markets where companies largely follow each other and segment customers in similar manners. This is represented by the middle row in Figure 3.2.

True competitiveness requires customer orientation. Even though customer orientation is viewed as a component of market orientation, there are some important distinctions between market-oriented and customer-oriented organizations. Market orientation also focuses more on internal and competitor activities and is consequently based on the activities of a range of actors on the market. Customer orientation focuses on in-depth knowledge of the customers and their problems as well as how the company builds relations with its customers. Customer orientation involves tailoring actions according to customers’ market activities and thought processes.

Figure 3.2 The interrelated nature of market and customer orientation

Offering a good product or service may have been sufficient at one time, but due to heightened competitions this is not the case anymore. The primary task of a company and its employees should be to help solve the customers’ problems, which requires close customer proximity and an understanding of their actions carried out in their own context. This development is described in the following way by William Clay Ford Jr., great grandson of Henry Ford:

If you go back to even a very short while ago, our whole idea of a customer was that we would wholesale a car to a dealer, the dealer would then sell the car to the customer, and we hoped we never heard from the customer—because if we did, it meant something was wrong.

Today we want to establish a dialogue with the customer throughout the entire ownership experience. We want to talk to and touch our customers at every step of the way. We want to be a consumer products and services company that just happens to be in the automotive business.11

Even though the quote is in reference to Ford, it applies to other companies as well. The Swedish company SKF, for instance, specializes in ball bearings, but so do other companies as well. What SKF truly excels in is—in somewhat simplified terms—how ball bearings should be mounted and their operational conditions. The first-mentioned example is an expression of market orientation, while the last-mentioned one represents customer orientation. Claiming that customers are important and placing them at the center of corporate strategies is a taken for granted in many companies, but the important question to ask is how these words can be turned into actions.

The two most recent meta-analyses of antecedents of new product success have shown customer orientation to be a consistent primary success predictor. Using a standard construct to define customer orientation, a study of service innovation in banks unsurprisingly found that customer orientation was a significant antecedent of service innovation success for the banks. The effect size, 0.22, was large. This effect size roughly indicates that nearly a quarter of the variation in the success of the service innovation could be explained by the degree of customer orientation within a bank.12

Summary

Organizations that want to be successful in service innovation should (1) develop proficiency in user research, and (2) strive to develop a true customer orientation. Organizations should particularly focus on using proactive user research tools.

Focusing on value-creating processes, that is, understanding the customers’ wishes and facilitating their everyday activities, requires a deep understanding of their daily life and behavioral patterns. This information is not easily acquired, due to the difficulty in understanding the value of “sticky,” “contextual,” and latent knowledge and information, which, in turn, makes it difficult to transfer. Conquering this challenge requires putting the customers in the driver’s seat and letting them lead part of the development. Entire organizations might also have to be rewired to enable new ways of absorbing and distributing customer information, which, in particular, highlights how important customer information is in an organization—the absence of customer information will make it difficult to understand how a company can support its customers’ processes.

Action questions for the service innovator:

What is your assessment of your employees’ level of knowledge of customers and users?

Who in your organization observes users creating value with your services?

How is the knowledge gained (1) saved and (2) put to work?

If someone contacts your organization to tell you how to improve your services, how will your organization respond?

What is the ratio between the amount of time spent on internal organization processes and the time spent on understanding the customers’ value-generating processes?

Is your organization truly “customer oriented” (or user oriented)?

The main sources of inspiration for this chapter are:

The following articles respectively capture service innovation together with the customer, the ability of organizations to capture external information, different methods for customer interaction in development processes, communication in innovation processes, the importance of “sticky” information, and, finally, the importance of employees.

Alam, I. 2002. “An Exploratory Investigation of User Involvement in New Service Development.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30, no. 3, pp. 250–61.

Cadwallader, S., C. Jarvis, M. Bitner, and A. Ostrom. 2010. “Frontline Employee Motivation to Participate in Service Innovation Implementation.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 38, no. 2, pp. 219–39.

Cohen, W.M., and D.A. Levinthal. 1990. “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35, no. 1, pp. 128–52.

Edvardsson, B., P. Kristensson, P. Magnusson, and E. Sundström. 2012. “Customer Integration Within Service Development: A Review of Methods and an Analysis of In Situ and Ex Situ Contributions.” Technovation 32, no. 7, pp. 419–29.

Engen, M., and P.R. Magnusson. 2015. “Exploring the Role of Frontline Employees as Innovators.” The Service Industries Journal 35, no. 6, pp. 303–24.

Ettlie, J.E., and M.D. Johnson. 1994. “Product Development Benchmarking Versus Customer Focus in Applications of Quality Function Deployment.” Marketing Letters 5, no. 2, pp. 107–16.

Gustafsson, A., P. Kristensson, and L. Witell. 2012. “Customer Co-Creation in Service Innovation: A Matter of Communication?” Journal of Service Management 23, no. 3, pp. 311–27.

Schirr, G.R. 2012. “Flawed Tools: The Efficacy of Group Research Methods to Generate Customer Ideas.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 29, no. 3, pp. 473–88.

Skålén, P. 2010. “Service Marketing and Subjectivity: The Shaping of Customer-Oriented Employees.” Journal of Marketing Management 25, no. 7–8, pp. 795–809.

von Hippel, E. 1994. “‘Sticky Information’ and the Locus of Problem Solving: Implications for Innovation.” Management Science 40, no. 4, pp. 429–39.

We also refer to closely related areas such as market orientation, which, in actual fact, constitutes an entirely separate theory. More information on market orientation is available in:

Narver, J.C., and S.F. Slater. 1990. “The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability.” Journal of Marketing 54, no. 4, pp. 20–35.

We have also referenced some case descriptions:

Flodin, S., T. Nelson, and A. Gustafsson. 1997. “Improved Customer Satisfaction Is a Volvo Priority.” In Customer Retention in the Automotive Industry, eds. I.M. Johnson, A. Herrmann, F. Huber, and A. Gustafsson. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Olson, E.L., and G. Bakke. 2001. “Implementing the Lead User Method in a High Technology Firm: A Longitudinal Study of Intentions Versus Actions.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 18, no. 6, pp. 388–95.

____________

1 Kristensson, P., A. Gustafsson, and T. Archer. 2004. “Harnessing the Creative Potential Among Users.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 21, no. 1, pp. 4–14.

2 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3147148/He-gr8-man-Inventor-text-message-Matti-Makkonen-dies-aged-63.html

3 Witell, L., P. Kristensson, A. Gustafsson, and M. Löfgren. 2011. “Idea Generation: Customer Co-Creation Versus Traditional Market Research Techniques.” Journal of Service Management 22, no. 2, pp. 140–59.

4 Schirr, G.R. 2012. “Flawed Tools: The Efficacy of Group Research Methods to Generate Customer Ideas.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 29, no. 3, pp. 473–88.

5 Schirr, G.R. 2012. “User Research for Product Innovation.” In The PDMA Handbook of New Product Development, eds. K.B. Kahn, S.E. Kay, R.J. Slotegraaf, and S. Uban. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118466421.ch14

6 Fullerton, R.A. 1988. “How Modern is Modern Marketing? Marketing’s Evolution and the Myth of the “Production Era”.” The Journal of Marketing pp. 108–125.

7 Griffin, A., and J.R. Hauser. 1993. “The Voice of the Customer.” Marketing Science 12, no. 1, pp. 1–27.

8 May, M.E. November 16, 2013. “When It Pays to Listen to Users ... and When It Doesn’t.” Innovation Excellence (blog). www.innovationexcellence.com/blog/2013/11/16/when-it-pays-to-listen-to-users-and-when-it-doesnt

9 Jaworski, B.J., and A.K. Kohli. 1993. “Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences.” The Journal of Marketing 57, pp. 53–70.

10 Ettlie, J.E., and M.D. Johnson. 1994. “Product Development Benchmarking Versus Customer Focus in Applications of Quality Function Deployment.” Marketing Letters 5, no. 2, pp. 107–16.

11 Garten, J.E. 2008. The Mind of the CEO, 139. New York: Basic Books.

12 Schirr, G.R., and A.L. Page. 2009. “Antecedents of Service Development Success: A Culture-Tools-Process Model.” American Marketing Association Winter Conference 2009, p. 27, eds. F.L. Tampa, K. Reynolds, and J. Chris White.