Customers as Cocreators in Service Innovation

The more you engage with customers, the clearer things become and the easier it is to determine what you should be doing.

—John Russell, Chairman of Harley Davidson

... the role of the customer is essentially that of a respondent: speaking only when spoken to.

—Eric von Hippel, Professor at MIT

This chapter covers customers taking active roles in service innovation. The most pertinent example of active customers is lead users. Lead users take matters into their own hands and innovate what they are most in need of. Lead users are identified as those who stand to most benefit from product advances, but are often identified by the fact that they are already innovating. Customer involvement encompasses how companies may identify and cooperate with those customers who possess a potential for innovation. We also discuss ethnography, a user research method used to understand the customer’s value-creation processes in depth.

Preview of Action Questions

What opportunities do your customers have to participate in your organization’s service innovation process? If motivated users are engaged in your organization’s innovation process, how would you benefit from that?

Who are the lead users—the creative users who have the most to gain from innovation—if you innovate the service they already have ideas for?

Are you experimenting with new features or models of your services?

Who Has the Most Innovative Ideas?

Imagine the following scenario: The manager at a large corporation that offers services based on technical solutions asks all employees in its development department to write down their best ideas for future innovations. A number of users are also invited to come up with ideas for the company’s future range of innovations. More specifically, the users are asked to create ideas based on situations they experience in which they feel that a service would facilitate their value-creation processes, that is, that would enable them of achieving goals they experience are meaningful for them in their everyday private or working life. Thus, the customers are basically asked to create solutions they would personally find useful. The ideas for solutions that the customers suggest are constrained to be based on needs, challenges, and wishes that they have personally experienced. Customers are instructed to not simply brainstorm ideas—the ideas must arise from situations that they have experienced. The company wants to establish a connection between user ideas and value-creating processes in context.

The company has now collected two groups of ideas; internal development ideas from developers within the organization and development ideas submitted by customers, based on their personal experience. With this scenario at hand, what do you think is the answer to the following questions:

Who do you think generated the most creative ideas for future service innovations: the personnel at the research and development (R&D) department or the customers? Why?

Is the R&D-employees understanding of what the users would benefit from being aligned with customers’ actual needs and wants?

Are the R&D personnel capable of predicting what future solutions the customers will need?

Were the customers sufficiently creative, or would it better to ask trained staff (such as R&D personnel) instead?

When researchers at Service Research Center (CTF) carried out a study of cell phone services designed in the aforementioned manner, results showed that the customers presented the most innovative ideas. Customers were more creative and their ideas generated more user value (as assessed by both R&D personnel and other customers). In sum, customers generated ideas that solved real and significant problems on their own.

In assessing all the ideas for future service innovation, the senior managers leading this study did not know which ideas were submitted by the customers or employees respectively as they were coded in an anonymous way. The ideas were also evaluated by several different parties—groups of customers and employees alike took part in the process. However, regardless of who evaluated the ideas, the result was the same: The customers’ ideas were better. How is this possible?

This question is addressed throughout this chapter. Customers seldom get the chance to engage as actively as in this study. Customers are too rarely given the opportunity to participate in development processes at all. Most commonly, they get the chance to respond reactively to questions made up on beforehand, many times by giving ranks on a couple of items in a survey or by sitting in and talking in a focus group. We believe that customers must be given tools to facilitate service innovation involvement. Companies must use the right user facilitation method in the right situation. If these methods are not used, acquired user information may be based solely on limited memories and recollections of existing products. As noted in Chapter 3, incomplete information from customers and users unable to visualize a new service often leads to service innovation failures.

How Are Customers Involved?

Companies sometimes claim that their customers already are involved in their innovation processes. But what do their customers and users actually do? As previously mentioned, customers may be asked to give their thoughts on an existing offering used during the last six months or to voice their opinions on an almost fully operational prototype. Another common operation is to send long satisfaction surveys to customers, which typically results in low response rates. These approaches are still useful to some extent but are radically different from the knowledge your organization can collect when letting users act as a source of inspiration or as partners in development processes. Customers or users are often asked about aesthetics, design, and pricing. This means that they may be included too late in the process and asked to provide information that is not significantly related to their value creation, which should be the main goal of the innovation process. It can be said, somewhat in jest, that such customer participation encompasses decisions on what color the offering should have, or the design of the subsequent sales campaign. Again, this might be useful information for an upcoming launch, but does not include detailed problem-solving information about customer value-creation processes.

When users participate from the start in an innovation process, suggesting what should be developed and why it is important, they provide deep user information and knowledge. Usability of the service or the problem-solving capability of the offering is vital to be successful. True customer and user involvement can also give insight on how the core activities of the service should be designed, all this with the intention of innovating a service that will lead to value-cocreating processes for the customer.

In accordance with the service innovation model presented in Chapter 4, we urge everyone involved in service innovation to spend time with their customers in the customers’ environment, observing and engaging them during the value-creating processes. Ensure that users are equipped with an appropriate set of “tools” to modify and test the service or physical product as it will increase the likelihood that submitted ideas are useful. This set of tools depends on what the service innovation process encompasses—in, for instance, telecommunication services, a mobile phone is a good tool to let customers more easily share their thoughts on future mobile services. A mobile phone allows customers to take pictures, register their thoughts and experiences, and submit them to the company. In health care facilities, where mobile phones are not always allowed, the act of blogging or writing a diary covering one’s experiences has shown to be a successful platform. By providing the customers with the enabling tools, the sharing of information about value creation will be facilitated.

Another example of tool use can be found in the travel industry, where select customers of a travel firm are encouraged to send a text message every time something extraordinary happens. Text messages can also be sent to a target customer group at different times to inquire about how they are occupied, to get information about value creating opportunities (and challenges). Academically procedures such as these are referred to as “experience sampling”.

Selecting which customers should participate in the service innovation process is very important. Our research, and that of others as well, shows that motivated participants should always be at the forefront. Selection should not involve identifying any kind of average customer or employment of random selection procedure.

Early Involvement

Research articles show increased likelihood of success when letting users participate in early stages of the innovation process. Although it is always beneficial to listen to customers, the value of customer input can be significantly enhanced by involving them as early as possible in the development process, which is in contrast to current industry practice. For service innovation, it is also important to not forget to involve customers also later in the development process when there exists a description or prototype of the service. This allows for smoother adoption processes. Too many potential innovations never get a chance as companies have not considered how customers will adopt the new service.

Early involvement to some extent requires different techniques than late development input. With inspiration from research on information systems we have created a descriptive model aimed at elucidating this issue to companies by covering the manner in which they listen to customers, as six stages of customer or user involvement:

We do not listen to customers. New products originate from new technology and competence.

We do not listen to customers. However, we base our product development on our perception and estimates of customer needs.

We listen to customers via questionnaires, interviews, or focus groups but do not involve them in our development processes.

Customers are involved in the development process by testing new products (e.g., in user-labs) and giving feedback.

Customers are actively involved in the development process and allowed to submit their own ideas.

The customers develop products for themselves since there are no value creating solutions available on the market.

We note that several companies seldom reach past stage 3 of this model, which represents the traditional market survey or reactive methods (interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires) mentioned in Chapter 3. Stages 4 to 6 are markedly different from the first three stages; they entail far greater customer involvement in the innovation process. In the last two stages (5 and 6), customers are in fact the most active party as they carry out the bulk of the innovation process themselves. Stage 6 represents Lead Users who develop innovations for themselves when no market solutions that meet their needs exist.

Lead Users

The notion that all new products or services originate from companies is a commonly held belief. When a product or service, old or new, is used and found to be lacking in some way, statements such as “it’s strange that they (the company) don’t do anything to fix this” are common. The belief that companies invariably sow all seeds of innovation seem well rooted in the human mind. However, to budge this belief just a little bit, consider how skilled we humans are at adapting to new situations— our problem-solving skills peak whenever a crucial situation occurs. Also, people are in general both more well-educated and can obtain new knowledge much faster today than, let’s say, 25 years ago. In the innovation history, users have proven to be the source to ideas for, for example, rollerblades, the coffee filter, and the Frisbee. Our point is that it is not strange that customers are good at finding solutions, even if it is not part of their day job. What is strange is that we have the view of companies as the originators of innovation, such a belief is narrow minded and research suggest that we should adjust our view of innovators to also incorporate the customer or user.

Figure 5.1 illustrates a modern irrigation system used on large arable land areas. It is referred to as a “center pivot irrigation system” in technical terminology. This innovation is absolutely extraordinary as it enables irrigation of vast areas of land in a cost- and energy-efficient manner. An irrigation system such as this is obviously available on the market via various industrial companies that most likely manufacture, sell, and offer ancillary maintenance services as well. The development trends of this type of large industrial irrigation systems have followed the innovation logic previously presented, that is, they have been developed by different companies in a number of iterations, eventually becoming the modern and indispensable service for farmers shown in Figure 5.1. Center pivot irrigation systems have proven to be very useful, allowing farmers to grow crops in desert environments where water is a scarce resource. This service innovation has provided value of significant importance to social development.

Figure 5.1 A modern irrigation system based on the center pivot principle

Source: www.valleyirrigation.com/valley-irrigation/us/mediaroom/photos#centerpivots

The interesting aspect of the center pivot irrigation system is that it did not originate from the manufacturers that today build them, but instead from a lead user who was facing a problem and had a strong need to solve it. Note that even for a complex industrial business-to-business offering, a user was the creative source behind the innovation. Frank Zybach is an American farmer who was not satisfied with the harvest produced on his farm. He had a strong desire to develop an irrigation system that would enable him to run his farm more productively. How was it possible for an ordinary farmer to develop such an important innovation in an established industry that was serviced by world-class corporations?

The secret behind Frank Zybach’s innovation (see Figure 5.2) was that he had (1) a very strong need for large-scale irrigation, (2) a history that had given him an aptitude for problem solving, and (3) the tools to fashion a working system based on his ideas. A strong need, which involves intrinsic motivation, connected to knowledge and the tools to create a solution is, as shown by research, a winning formula for innovation.

Frank Zybach grew up on the countryside and encountered the problems of poor irrigation firsthand at an early age. Frank’s father was a smith and taught him how to develop water management systems based on the pressure that develops when water is led through interconnected steel pipes. As such, Frank had the tools required to solve the problem at hand. These skills, coupled with the strong needs he had of improving as a farmer, led to his successful innovation. The irrigation system he developed also contained several interesting details but the concept of interconnecting pipes to power the rotation around its own axle was the most important one. Water fed from the pivot point in the center is then distributed into long pipes. This resulted in the ability to irrigate numerous crop circles and revolutionized the entire agricultural landscape of the United States. It was later picked up by several companies that further developed the system and distributed it to the rest of the world.

Figure 5.2 Frank Zybach’s own irrigation system

Source: www.livinghistoryfarm.org

A similar example, described in his research around Lead Users by MIT-professor Eric von Hippel in a Sloan Management Review interview,1 is the invention of the heart–lung bypass machine by Dr. Heysham Gibbon. Dr. Gibbon was frustrated by a lack of product offerings from the medical device companies to help patients dying from circulatory problems. So he developed the bypass machine himself. Furthermore, one of the authors of this book worked in the financial trading business when most financial securities and derivatives trading moved online: He observed that most of the innovations in how orders entered online originated from active traders who were trying to get an edge over competitors. A final example of user innovation is the phenomenon of open source software, which includes major “brands” such as Apache and Linux, and is totally reliant on innovation from users.

Despite the fact that key innovations in agricultural irrigation, medical devices, online trading, and countless other services and physical products came from users with a strong desire who were capable of solving the problem at hand, most companies still seem stuck in the belief that their development teams or R&D centers are the sole originators of innovations. This belief is in contrast to how to the key reasons why Lead Users, outside the firm, develop innovations that provide value for themselves. Again, the key to these innovations was a strong need for the innovation from users who, from experience and occupation, have developed skills and insight into possible solutions. Coupled with motivation that stems from a strong need this makes a perfect ground for service innovation. This represents a completely different mode of operation for service innovation.

Why do so many people stubbornly cling to the notion that only companies should develop innovations? Perhaps, the cases of Frank Zybach, Dr. Gibbon, the online traders, open source software users, and the many other examples available are really only “exceptions proving the rule” that new products and services should indeed be developed by companies without any customer involvement? However, studies by American innovation researcher Eric von Hippel have actually shown that this is not true (see Table 5.1).

Many users try to improve products and services. According to one avenue of research, at least 6 percent of the users generally make adjustment to their purchased offerings that could be labeled innovations. The numbers in Table 5.1 are based on explainable logic pointing to the fact that surgeons probably care a lot about their work and that they are very much interested in any measure capable of facilitating or improving the result of their work. The same principle applies to mountain bike cyclists—regardless of being regular enthusiasts or bona fide professionals, they use their bicycles to a great degree and have thereby acquired experience and knowledge that can be used to further develop their bicycles in different aspects. Whether it be irrigation systems, medical devices, trading screens, software, mobile phones, pellet burners, hotel stays, or broadband services, customers have identified problems and performed or suggested innovations to solve the problems. The key is combining the experiences from users with problem-solving skills and a strong motivation. Add tools for innovation to that and invited customers will be able of contributing to the innovation processes of any company within any industry.

Table 5.1 The number of innovations created by users in different markets

Products |

Sample |

Percentage of innovations developed for personal use |

CAD software circuit boards |

136 participants at a CAD conference |

24.3 |

Library information systems |

Librarians at 102 libraries in Australia |

26.0 |

Surgical equipment |

261 surgeons at surgical clinics in Germany |

22.0 |

Extreme sport equipment (e.g., skydiving) |

197 members of various clubs that organize extreme sports |

37.8 |

Mountain bike equipment |

291 mountain bikers in a particular region |

19.2 |

Source: von Hippel, E. 2005. Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Astute readers might notice that the majority of innovation examples cited by Dr. Eric von Hippel involved lead users and physical products. Research also shows the value of lead users in the innovation of traditional (direct) services. One research study carried out in the banking sector, also by von Hippel, showed that nearly 40 services had been developed by regular users and subsequently developed further by bank. These new services were mainly in security and online banking. Online trading and open source software examples were already cited in this discussion. The service company called Weight Watchers was started by Jean Nidetch, who was unhappy with her weight and unable to find solutions that she found satisfying to help her. She started her own club consisting of female friends who supported each other, and the result is the commercial weight loss program that is top rated by US News. Again, skills with how to tailor-make a solution coupled with a strong need makes a fertile ground for service innovation.

User innovation is natural for products viewed as services: One of the key tenets of service marketing—a part of the definition of service—is the cocreation of value by users and producers.2 Companies that view themselves as service providers are therefore familiar with the cocreation of value concept. Logically, a focus on and understanding of the value-creation process and implementing user innovation should be easier under a service paradigm due to this acknowledgment of the cocreation of value.

Eric von Hippel’s research into lead users has received increasing amount of attention in recent years. The research team of von Hippel’s at MIT in Boston decided to examine what the potential of lead users consisted of compared to ideas developed internally. Table 5.2 shows the result of this experiment. The comparison between the two different principles that are based on creating ideas internally and identifying them as lead users, respectively, shows that there is great potential for innovation processes that are carried out in an outward–inward paradigm. Lead users who are aligned with their context simply generate better ideas. Include customers in the service innovation processes, especially your lead users. Their ideas are more innovative and profitable.

In the study of cell phone service that started the chapter, customers were found to have more original value creating ideas not because users are inherently more creative than R&D staff—rather, customers have unique knowledge of situations of value-creating processes important to them, as well as important details of their situations and environment. They have knowledge and skills about the use of the solution while the employees within a firm have knowledge and skills about the solution. If these two entities of knowledge can be connected innovation processes will run a lot smoother. The solution most often utilizes resources the company has access to and knowledge of. The need often arises in situations in which the user has skills and knowledge. While the company most likely possesses the most knowledge of the process and technology of a solution, the customers are in closest proximity to their own needs.

Table 5.2 Comparison between innovation ideas created internally and those that originate from lead users

Lead user ideas |

Product development ideas |

|

Creativity (scale 1–10) |

9.6 |

6.8 |

As yet unknown customer values (scale 1–10) |

8.3 |

5.3 |

Market share after five years |

68% |

33% |

Sales after five years |

US$146 |

US$18 |

Success probability |

80% |

66% |

Source: Lilien, G.L., P.D. Morrison, K. Searls, M. Sonnack, and E. von Hippel. 2002. “Performance Assessment of the Lead User Idea-Generation Process for New Product Development.” Management Science 48, no. 8, pp. 1042–59.

Users are simply more knowledgeable of their own reality or value-creation processes than the R&D developers employed on behalf of the companies. Imagine a situation in which a 40-year-old, well-paid, professional, male engineer is tasked with finding solutions that appeal to an unemployed teenage girl who has grown up without exposure to information technology solutions. It goes without saying that it would be very difficult for the engineer to identify with her needs as well as her situation and environment where the need is present. Contextual aspects far removed from our own context and needs are simply more difficult to envision. One example proving this fact is when packing clothes for a holiday far away in the sun on a cold winter morning, you have most likely packed one sweater or a pair of trousers too many simply because it is appropriate in your current situation.

The telephone communication company that we studied would hardly have been able to understand—even with expensive and extensive customer surveys—the venue and details of all their customers’ value-creating processes. It is unlikely that questions in in-depth interviews or user focus groups would be enough to identify the situations that occurred in their customers’ everyday life. When we subsequently allowed the customers to experience and base their feedback on situations that were important to them, and that occurred in their everyday life, a number of ideas arose that were based on situations that the company, even with a good portion of creativity, would not have been able to think of beforehand. All customer ideas were based on situations the customers had in fact experienced, which is the reason why they were regarded as creative and value creating. The ideas of companies are often instead based on existing and available technology, that is, they are developed in accordance with a paradigm, or logic, that we earlier (in Chapter 1) classified as inside-out. Our follow-up interviews with both customers and employees also showed that the customers based their solutions on rather ordinary, but still for the customer important, situations, while the employees relied on technical solutions they found interesting.

One random and interesting discovery we made in the study was that, when confronted, most customers, especially those who had suggested the ideas the researchers who assessed the merit of the ideas had identified as very creative, were surprised by the high ranking of their ideas. These innovative customers said something similar to: “I just based my solution on a situation I encountered once when I was downtown.” Thus, they were ordinary for the customer but gave creative insights to the developers within the company.

In research terms, customer involvement in service development is important because it is often carried out on site, which means that companies have tried to create important components of the service innovation specifically where it is thought to have a subsequent effect. In contrast, customer and user surveys that are carried out outside the context of use, for instance, in conference rooms, far removed from where the service is going to be used in the future, are less likely to provide an organization with much help into the innovation process. For finding service innovations, we recommend that the company leave the conference room and go wherever the value-creation processes occur. This applies to everyone except companies that sell conference room equipment!

A survey attempting to analyze, for instance, customer opinions on a number of gardening tools is best carried out during a pleasant spring day in the beginning of May when people are most likely to be working in their gardens, as opposed to using telephone interviews on an ice cold winter day. Similarly, it is difficult to get patient opinions on hospital stays after they have left the hospital and have perhaps already recovered. The experience will not be the same as when the patients were actually at the hospital with an illness. Most likely everyone who has stayed at a hotel have received, three to four days subsequent to the visit, a request to fill out a short satisfaction survey. Unfortunately, surveys as these will give the hotel manager very little information about how to improve the service of the hotel. If a hotel manager really would like to understand how to improve a hotel, they would do much better hanging around in the reception area talking and observing customers when they arrive and leave the hotel.

As shown in Table 5.3, there is an important difference between the previously mentioned lead-user studies and those in which customers are allowed to provide solution proposals based on situations they have personally experienced, as in the telephone company example. We refer to the latter as customer involvement. The essence of the lead-user method is that the users themselves both identify value-creating processes and create a solution to them, this is totally without any interaction of a company (the lead users engage in innovation because there are no solutions provided on a market). In our study, customers identified value-creating processes and suggested relevant ideas. However, they never created or realized a complete solution. Most companies do not need to go as far as a complete solution since they can instead let the customers identify value-creating processes and potential solutions from which subsequent solutions are developed. In light of Chapter 4, this means that we involve customers in the understanding of the process, and the goal of the company can still be to identify and implement possible solutions.

Table 5.3 Lead user methodology compared to customer involvement

Lead user methodology |

Customer involvement |

The users identify a strong need, which, if solved, would lead to value-creation processes. They create the solution to the problem on their own as there is no existing market solutions available. |

Users identify problems in the value-creation processes but do not create any solutions, only ideas for solutions, or prototypes for how a solution that they would experience valuable could function. An organization is working in partnership with the customer or user. |

We have participated in customer involvement projects in health care. In one of our studies, patients were provided with idea books in which they could write down how they experienced their illness when they experienced it. They were asked to describe the situation when the illness arose, and how they dealt with it. Those in charge of developing health care were given access to the patient ideas and could use that as important feedback of how the patients felt about their care and how the provided care contributed to the patients improvement of health. The project provided the health care staff with knowledge of problems experienced by the patients in their homes or when they were transferred between different parts of the health care institution, that is, essential aspects of the patients’ value-creation processes. Patients with chronic diseases in particular, such as cancer or chronic pain, are experts of their disease and know how to handle it on a daily basis. Some examples of the problems patients experienced was the difficulty of seeing what time it is at night when lying on one’s back without being able to move, how seriously a disease affects one’s ability to cope with three children as a single parent, or how to handle the sometimes contradictory advice given at different departments in the health care institution. These types of situations are typically not what health-care employees (i.e. nurses and doctors) are informed or know much about, nevertheless, it affects the value that the patient will experience from health-care service.

One of the authors worked for an online trading software company that provided free rent to an active online trading firm so that first-tier traders would be located just one floor below the company’s development staff. Engineers and product development managers observed their firm’s products in use and gathered live feedback from demanding cutting-edge (lead) users. The company found that the insight gained from value creation observation and real-time discussion was worth far more than the rent and software license subsidy granted to the trading firm. Fortunately, such subsidies are rarely needed: Users are often very pleased, even honored, to participate in service innovation without any subsidy.

Understanding Customer Contexts—Ethnographic Studies

Moving from a discussion of user innovation and user involvement we are now to discuss an intensive user research method, namely the ethnographic research method. We mentioned an ethnographic study of customers in Chapter 3 along with other user research techniques, but felt that more complete discussion of ethnographic techniques is motivated.

Service innovation relies heavily on understanding user needs and situations or contexts, as established in Chapter 4. Successful service innovation is always based on an understanding and enhancement of the value-creating processes of the user. Only after understanding the value-creation process and associated problems should the company be able of determine what resources are needed in order to realize the innovation of a new value proposition (see Chapter 4). In traditional innovation processes, companies often do the exact opposite: They begin by researching and developing an offering they believe is profitable or attractive and then examine how it might be useful to customers. Analyzing the situation from a broader perspective we suggest that the customer’s context represents the lifeblood in service development, while the company’s laboratories represent the lifeblood in traditional product development.

One problem with the development-first, then understanding, innovation processes is that the company risks incurring great development costs that might not be justifiable in relation to profits of future sales, unless it manages to persuade the customer to purchase the offer despite not being a perfect match.

Ethnography is a tool borrowed from anthropology based on holistic logic stipulating that aspects of an entity or process cannot be understood or analyzed independently. Ethnographical studies often follow users during the activities in which value is generated. As a result, the context where value is being created is naturally integrated in ethnographic research.

A study of the Scandinavian airline, SAS, examined air travelers’ perceptions of their trip by filming and interviewing them in situ while at the airport, at check-in, on-board, and at the baggage claim, following them until reaching their final destination. SAS also had travelers write diaries during these different stages where they detailed elements of pleasure and annoyance. It is easier to acquire insight and understand value-creating processes if the travelers in question are in the particular situation where value creation occurs, as opposed to asking them after a period of time to provide a recollection from memory (as was also pointed out in the hotel example a couple of pages ago). Research has shown that many recollections of well-being and irritation fade quickly.

There are many other examples of useful marketing insights from ethnographic research. Nike has sent anthropologists to inner-city playgrounds to watch urban youth, who have been leading fashion setters for sport footwear, use and wear expensive shoes. On some occasions, a truck load of shoes were left to see which colors and styles were taken and which were later worn on the basketball courts. An academic researcher, trying to understand how high-tech firms performed marketing, gained insight from observing a tech firm working for several months.

An interesting (and strange) example of insight into a value-creation process from in-depth qualitative research was the case of new home insecticides for roaches. A target pool of low-income southern women agreed that products that were test marketed—plastic trays that killed roaches discretely—worked better and were less messy than roach sprays. But they continued to buy the sprays. After interviews, observation, and other qualitative research, the marketing team determined that these customers viewed cockroaches as symbols of the men in their lives. “Killing the roaches with a bug spray and watching them squirm and die allowed the women to express their hostility toward men and have greater control ....”3 This would have never been a question on a survey. No one at the company was likely to guess that there was a positive user experience from watching the roaches after they were sprayed!

A more mainstream example of the power of ethnographic study is studies of mobile phone use in developing countries. When mobile phone use was still relatively new, several mobile phone companies sent ethnographic teams into China, India, and other developing countries to observe how the phones were being used in remote villages that had new mobile service. They found that due to high cost but corresponding high value created, extended families and even whole villages were finding ways to share cell phone service. The findings from the studies led to the development of low-cost Internet phones and special service bundles suited for the observed phone sharing.

Ethnographical research breaks many of the traditions used as guidelines in classical market research. For instance, ethnography does not rely on random selection of different subjects, but instead attempts to identify users capable of making extraordinary contributions. The approach is similar, but not identical, to identifying lead users. These rich subjects can then be used to find additional subjects. Ethnography relies on close collaboration between said users and their personal experiences that leads to insight and understanding of the situations that either facilitate or obstruct value-creation processes. Understanding how people live makes it possible to discover otherwise elusive trends that can provide companies with future strategic leads.

Take smartphones as an example: Ethnography can identify differences between technologically savvy teenagers who have been using mobile phones since first grade and older generations of people who grew up when mobile phones did not even exist. Ethnographical studies aid in transferring the perspective of a consumer group to employees at a company. It is worth noting that the electronics company Intel has some 24 ethnographically trained persons in its staff.

Let us examine the previously mentioned study of SAS in more detail. Through several ethnographical studies, a significantly clearer picture of air travelers’ real needs developed. Having originally focused on safety and pricing as the customers’ central needs, SAS was able, through the studies, to identify other processes through which it could support customers via a cohesive traveling process and thereby develop their brand while maintaining relatively high price levels.

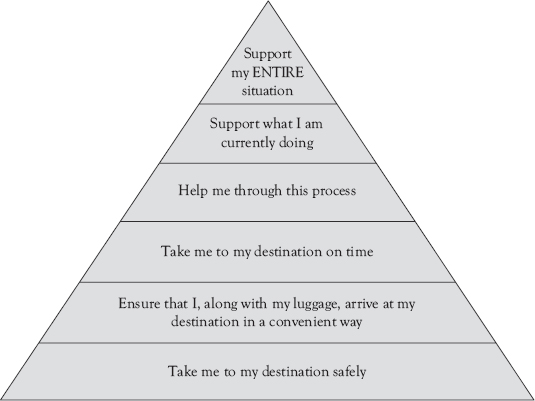

Figure 5.3 shows a hierarchy of experiences in which air travelers have rated the priority of value-creation processes. The first stages in the figure contain essential elements such as safety, baggage handling, and timeliness. When the airline is able to meet the requirements that transport the traveler safely from point A to B, it can advance upward through the pyramidal hierarchy. In order to compete with other companies, subsequent amenities might consist of providing travelers with the opportunity to work when traveling, which includes everything including Wi-Fi, workspace, and the ability to speak uninterrupted on the phone. However, this also includes resources that assist passengers when traveling to and from the airport. One example of supporting the traveler’s entire situation (the topmost section of the pyramid) is awarding loyalty points that can be used to rent cars or pay for hotel stays. Providing support in this way is a prime example of service logic: The company supports a user and his or her value-creation processes.

Figure 5.3 Hierarchy of experiences developed from air travelers via ethnographical methods4

Many innovations involve new technology that has not always been developed with the customers’ value-creating processes in mind, but rather because it has been technically possible. Service innovations that support value-creation processes can obviously, in many cases, consist of new technology, but they are often accompanied by different types of activities on behalf of frontline staff as well. These activities in particular, as noted in Chapter 4, are difficult to copy, ranging from the slightest contact between employee and customer to large chains of interlinked activities in the form of actions that employees carry out to support the customer’s value-creation processes. This domain makes it possible to speak in terms of complete solutions that support what customers want to do.

Frontline staff plays an important part in ethnographical studies. In the aforementioned SAS study, a number of interesting findings were made when staff was given detailed descriptions of how to carry out the studies. The first was the realization that they actually encountered a number of customer problems every day but had become so desensitized that they did not regard them as problems or even considered measures to eliminate them permanently by targeting the root cause. Instead, they solved every specific situation ad hoc. The second finding was that customers were highly adaptive and did not regard said problems as customer problems either. Therefore, they were not able to recognize or remember all sources of annoyance when queried by the staff, in effect also undergoing a process of desensitization in which problems were taken for granted.

The ethnographical studies made it possible for SAS to discover needs that were not explicitly stated but important nonetheless. SAS also discovered that customers had created minor workaround routines, which encompassed everything from putting up Post-it notes with the ticket number on the bag to finding ways of cramming the luggage into the overhead bin, as well as finding positions in the airplane seat that were suitable when sleeping. Via ethnographical survey methods, the staff eventually discovered and came to understand all of these small impediments, which enabled the company to develop solutions that not only eliminated sources of annoyance but also facilitated and improved the customers’ overall traveling experience.

Facilitate Customer Cocreation of Service Innovation

Customers are becoming increasingly involved in the service innovation processes in organizations. Compare what it was like to enter a retail establishment 50 years ago with the condition today. Customers now walk around the store collecting products, placing them in their shopping bag, and often making the payment without any interaction with staff. The same phenomenon is observed at gas stations, airports, banks, and so on, and the overall trend is moving toward a situation in which customers are taking care of the processes themselves. Self-service is another challenge and opportunity for service innovation. It is important for organizations to ask themselves what kinds of processes they can let their customers carry out themselves, with better results for their value-creating process as a promising goal. Interestingly, vice versa is also true, organizations can also ask themselves what processes the customers already are doing, and see if they can innovate something that enables them to do it instead (again, if enhanced value-creating processes occur for the customer).

What are the key factors that facilitate customer involvement, whether during the actual moment of consumption or during the stages of the development process? Research suggests six factors that facilitate involvement from customers as cocreators in service innovation processes.5 The odds of customer involvement in service innovation processes improve if:

They have expertise. All service innovation processes that encompass areas such as exercise, hobbies, cars, renovations, or do-it-yourself (DIY) activities are facilitated if the customers have expertise. Think of the examples of the farmers, doctors, and traders in our discussion of user creation.

They wish to be in control. Service innovation processes that encompass offers in which the customer or user wishes to be in control of the results always facilitate cocreation. Customer desire for more control over their personal finances has been a major factor in online banking development.

Physical capital is available. Service innovation processes that require physical capital are obviously facilitated by the fact that the requisite tools, space, or other resources are available to certain customers. For instance, in software development, customers must install certain software before participating in service innovation processes.

They wish to minimize risks. Service innovation processes are facilitated when customers are strong proponents of risk minimization. Patient participation in health care innovation is more likely if it results in a lowered risk of becoming ill or experiencing negative consequences from a disease.

Their involvement leads to experiences. One of the primary reasons why customers participate in service innovation processes is that they find them enjoyable and that the act of creating creates value. For instance, many web-based companies encourage customers to submit ideas of new foods, traveling services, or home-improvement projects.

The innovations lead to financial or need-related benefits. One of the deciding factors of customer participation in service innovation processes is whether or not it results in saving time and money. It can involve making improvement suggestions to the organization or providing ideas of how to develop a time-saving service. For instance, the motivation for railway customers to participate in service innovation is often that it will result in benefits to them, for example, a more reliable trip.

The aforementioned factors not only elucidate dimensions that facilitate customer participation in service innovation processes, but also the extent to which they will participate. The trend of motivated customers who want to participate in service innovation processes should lead companies away from the traditional mindset of “what can I do for you?” to an environment where customers are instead asked “what can we do together?”

Summary and Further Reading

The philosophy of this book is that the customer belongs in the driver’s seat to promote development of new offerings tailored to their own value-creating processes. Your challenge as a service innovator is to determine how to establish a functional process that enhances the development of customer value creation. This requires a conscious effort on your part to activate your customers and equip them with the necessary knowledge and tools to ensure that they successfully negotiate the challenge at hand. Perhaps hardest of all: You must be willing to actually place customers in the driver’s seat and learn both from them and with them. It is more easily said than done as research confirms that open and collaborative innovation processes are perceived as unfamiliar and difficult by most companies. However, this chapter has provided you with some important insights into the process of involving the customer into the development and is based on knowledge that we have had the privilege to apply on a number of companies, including Ericsson, TeliaSonera, Whirlpool, Public organizations, and a leading French bank.

Involve customers and users in service innovation. The result will be new services that better enables customer value creation. Our research indicates another side benefit: Customers involved in the innovation process are likely to become even more loyal customers and become evangelists for the new service if they are allowed to influence the development in their own desired direction.

Questions for the service innovator:

What opportunities do your customers have to participate in your organization’s development process?

Who are the lead users of your current services?

What sources does your organization use to generate ideas of future innovations?

Have other sources for ideas been investigated sufficiently?

Do you continue customer testing and research during the launch of a new service? Development?

Do you offer services that would benefit and evolve from continual A/B testing?

The main sources of inspiration for this chapter are:

The empirical studies where users proved to be better idea generators than company employees, is well documented in the following articles:

Kristensson, P., P. Magnusson, and J. Matthing. 2002. “Users as a Hidden Resource for Creativity: Findings from an Experimental Study on User Involvement.” Creativity and Innovation Management 11, no. 1, pp. 55–61.

Kristensson, P., A. Gustafsson, and T. Archer. 2004. “Harnessing the Creative Potential Among Users.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 21, no. 1, pp. 4–14.

Magnusson, P., J. Matthing, and P. Kristensson. 2003. “Managing User Involvement in Service Innovation: Experiments with Innovating End Users.” Journal of Service Research 6, no. 2, pp. 111–24.

Magnusson, P.R. 2009. “Exploring the Contributions of Involving Ordinary Users in Ideation of Technology-Based Services.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 26, no. 5, pp. 578–93.

We have also compared different data collection models to examine the efficacy of in-depth interviews and focus groups in relation to a more interactive milieu in which customers are activated in their own context. Said studies are documented in:

Kristensson, P., J. Matthing, and N. Johansson. 2008. “Key Strategies in Co-Creation of New Services.” Journal of Service Management 19, no. 4, pp. 474–91.

Witell, L., P. Kristensson, A. Gustafsson, and M. Löfgren. 2011. “Idea Generation: Customer Co-Creation Versus Traditional Market Research Techniques.” Journal of Service Management 22, no. 2, pp. 140–59.

This chapter is also based on additional ideas and concepts with regard to service development and service innovation. Some of the examples used are more elaborately described in the following sources:

Edvardsson, B., A. Gustafsson, M.D. Johnson, and B. Sandén. 2000. New Service Development in the New Economy. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Elg, M., J. Engström, L. Witell, and B. Poksinska. 2012. “Co-Creation and Learning in Health-Care Service Development.” Journal of Service Management 23, no. 3, pp. 328–43.

Schirr, G.R. 2012. “User Research for Product Innovation.” In The PDMA Handbook of New Product Development, eds. K.B. Kahn, S.E. Kay, R.J. Slotegraaf, and S. Uban. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9781118466421.ch14

A plethora of well-written articles and books exists on the subject of Eric von Hippel’s groundbreaking research. We have chosen to highlight five pieces here. The first one is a comparison of financial data that lead users generate for companies and the second one encompasses lead users within service companies. The third one in the following row is one of the first articles on this theme and the fourth is a book summarizing the research area. The last one is a shorter article of the same theme. More information about examples and business cases can be found on his website at MIT or at www.leaduser.com.

Lilien, G.L., P.D. Morrison, K. Searls, M. Sonnack, and E. von Hippel. 2002. “Performance Assessment of the Lead User Idea-Generation Process for New Product Development.” Management Science 48, no. 8, pp. 1042–59.

Oliveira, P., and E. von Hippel. 2011. “Users as Service Innovators: The Case of Banking Services.” Research Policy 40, no. 6, pp. 806–18.

von Hippel, E. 1978. “Successful Industrial Products from Customer Ideas.” Journal of Marketing 42, no. 1, pp. 39–49.

von Hippel, E. 2005. Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

von Hippel, E., S. Thomke, and M. Sonnack. 1999. “Creating Break-throughs at 3M.” Harvard Business Review 77, no. 5, pp. 47–57.

If the reader would like to further explore ideas in market validation, we recommend the footnotes in the list of the five processes, especially Brown on Design Thinking and Ries and Bland on Lean Innovation.

____________

1 von Hippel, E. 2011. “The User Innovation Revolution.” MIT Sloan Management Review, September 21. http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-user-innovation-revolution/

2 Bitner, M., W.T. Faranda, A.R. Hubbert, and V.A. Zeithaml. 1997. “Customer Contributions and Roles in Service Delivery.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 8, no. 3, pp. 193–205.

3 Alsop, R. 1988. “Advertisers Put Consumers on the Couch.” Wall Street Journal, May 13.

4 Ekdahl, F., A. Gustafsson, and B. Edvardsson. 1999. “Customer-oriented Service Development at SAS.” Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 9, no. 6, pp. 403–410.

5 Lusch, R.F., S.W. Brown, and G.J. Brunswick. 1992. “A General Framework for Explaining Internal vs. External Exchange.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 20, no. 2, 119–34.