CHAPTER 13

CUSTOMER-FOCUSED ORGANIZATION: STRUCTURE, RESOURCES AND SERVICE PROCESSES

“The firm should turn the organizational pyramid upside down – mentally and structurally. Its customers have done so long ago.”

INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses how to structure a service organization and manage service processes such that the service provider becomes customer-focused. The first half of the chapter concentrates on structural issues, such as the use of marketing departments or other organizational solutions, so that a total marketing process can best be facilitated. The rest of the chapter discusses how to plan and manage the service (production) process so that the interactive marketing process of a service provider is successful. A service system model and an extended servicescape model are presented. After having read the chapter the reader should understand the problems involved with organizing marketing in a traditional way in service contexts and how to find new service-oriented solutions, and know how to develop the service process so that a good marketing impact is achieved.

THE MARKETING PROCESS AND THE MARKETING DEPARTMENT

In conventional marketing thinking, which is based mainly on experience from consumer packaged goods, a marketing department is the organizational unit responsible for planning and implementing marketing activities. The logic behind this solution is, of course, that marketing can best be planned and implemented if all marketing activities are concentrated on and taken care of by a group of specialists. If marketing is seen as a function, as usually has been the case in the past, this also makes sense.

However, such logic requires that marketing as a process be separated from the other business processes and activities of the firm in a logical and manageable way. In mainstream marketing this way of organizing for marketing is considered appropriate. At the same time, however, an increasing amount of criticism of this has emerged over the last 40 years.1 According to this criticism, in the emerging business environment marketing cannot remain a specialist function or be delegated to one department where the specialists plan and implement all marketing activities of the firm. This need for marketing to break free from the marketing department was recognized very early in service marketing research, especially in the Nordic School of service marketing thought.2 The traditional highly-structured military model with its hierarchical charts-and-box structure is seen as old-fashioned in today’s business environment. Process organizations and project organizations have been used as a way of overcoming the problems in these functionalistic organizational solutions.

The development of virtual or network organizations also shows how traditional rigid solutions are becoming less effective. Such an organization3 includes a nucleus which puts together and manages a network of other organizations and actors, and its assets, processes and people critical to the success of the business exist and function both inside and outside the conventional borderlines of the organization. In such organizational solutions, relationships and the process nature of marketing are natural ingredients.4

Nevertheless, a brief look at standard marketing textbooks and journals reveals that the traditional marketing department is still most often offered as the standard solution. The same is true for the practice of marketing. However, when moving the focus from the established areas of marketing, such as consumer goods marketing, to newer areas, such as business-to-business relationship marketing and service marketing, one can see another picture, where marketing departments are less dominating or there are no formal marketing departments at all. The long-term marketing perspective and the recognition of the characteristics of long-term customer relationships of service firms and business-to-business marketing demonstrate that marketing is not solely the responsibility of marketing specialists, but that marketing activities are carried out throughout the entire organization.5 We thus have an organizational dilemma created by the fact that those who produce and deliver service carry out marketing activities for that service as part-time marketers,6 whether they know it or not and whether they accept it or not.

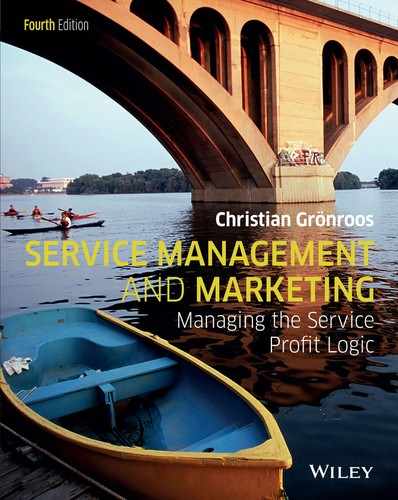

Figure 13.1 illustrates the position of marketing in a professional service firm, as in any service organization. The dotted areas indicate the marketing responsibilities of various functions. For example, the president, divisional and regional directors, consultants and assistants as well as all other employees have marketing responsibilities as part-time marketers, because what they say and do and how they do it may have an important impact on the future buying and consumption behaviour of customers. Simultaneously, they have responsibility for operations as well. In addition, people outside the formal organization may also make a marketing impact on behalf of the service provider. In the figure, clients and former employees are examples of such people. To take a bank as an example, the managing director, regional directors, loans director and tellers are employees who have similar marketing duties as part-time marketers.

The status of most employees in service operations is complicated. They have dual responsibilities because clearly a cashier, bank teller, waiter, hotel receptionist or maintenance technician must first be able to take care of his technical duties. However, at the same time most employees have to realize that the way in which they do their duties is a marketing task. Marketing activities are carried out by every employee who influences the customers of the organization directly or indirectly. In every service organization there are a large number of part-time marketers who have dual responsibilities: to perform their tasks well in a technical sense and at the same time in such a way that they create a good marketing impact. In many service organizations these part-time marketers outnumber marketing specialists in the marketing department many times over. In the words of Evert Gummesson, this is because ‘marketing and sales departments (full-time marketers) are not able to handle more than a limited portion of the marketing as their staff cannot be at the right place at the right time with the right customer contacts’ (emphasis added).7

FIGURE 13.1

The simultaneous responsibility for marketing and operations among the personnel of a service provider.

Source: Adapted from Gummesson, E., The marketing of professional services … an organizational dilemma. European Journal of Marketing, 13(5); 1979: p. 311. Reproduced by permission of Emerald Insight.

The main problem in most situations is the fact that the marketing department is mistaken for the much larger concept of a marketing process. The marketing process includes all resources and activities that have a direct or indirect impact on customer preferences and the establishment, maintenance and strengthening of customer relationships, irrespective of where they are in the organization. The marketing department, on the other hand, is an organizational solution which aims at concentrating some parts of the marketing process into one organizational unit. There is always a marketing process – that is, the use of resources which the customers are exposed to and influenced by – but a marketing department does not necessarily exist in a firm. Lately there has been a discussion of the role and importance of marketing departments in the literature.8 Introducing and using a marketing department as an organizational solution to handling marketing may at some stage be an acceptable step. By doing so, management may be able to create an interest in and at least a theoretical understanding of the importance of marketing to service providers. The introduction of a marketing department may, however, also have a negative effect, because it may become an excuse for the employees to forget about the customer and concentrate on their ‘real’ job. In the long term a marketing department, especially a dominating one, can easily become a trap, which in practice makes it difficult for the whole organization to think and perform in a true customer-focused manner.9

THE MARKETING DEPARTMENT AS AN ORGANIZATIONAL TRAP

In a consumer goods context, mixing the two concepts of the marketing process and the marketing department is not a serious mistake, because most of the contacts between the firm and its customers can be taken care of by the marketing department. The pre-produced product, sales, advertising and other planned marketing communication efforts, price and distribution channels, is what the customers see and are influenced by. A very limited number of customer-influencing activities take place outside the marketing department.

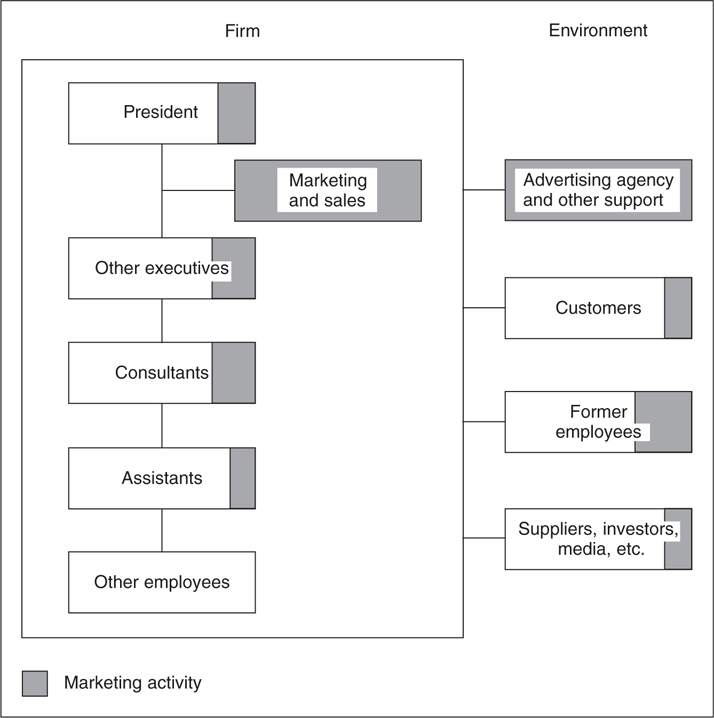

Figure 13.2 shows the differences between the coverage of a marketing department in a consumer goods context and in a service context. The circles in the figure denote the total marketing process, and the shaded areas illustrate the proportion of total marketing that can be handled by a marketing department. As can be seen, the difference between consumer goods and services is remarkable.

In most service contexts the situation is the opposite of that characterizing consumer goods. Normally only traditional marketing tasks such as advertising, pricing and sales promotion can be handled by a typical marketing department, whereas other marketing activities carried out as part of operations and other functions are outside the realm of this department. A large part of the marketing process is carried out by part-time marketers outside the marketing department. Nevertheless, growing service firms have, in the best consumer goods tradition, often been inclined to establish a marketing department, in order to maintain or even strengthen the market orientation of the firm. However, the long-term effect of this may easily be the opposite of that intended.

FIGURE 13.2

The marketing department versus the total marketing process.

A traditional marketing department cannot usually be responsible for the total marketing process of a service provider. The introduction of such departments, on the contrary, easily influences the organization in an unfavourable direction. People working in other departments, performing, for example, operational or administrative tasks, stop worrying about their customer-related responsibilities and concentrate on handling what they see as their ‘real’ job. The reason for this is clear. The firm now has marketing specialists in the marketing department; why should people in other departments bother any longer to do the marketers’ job? There is someone else to blame if things go wrong. The result is an increasing inward orientation and a less customer-focused performance. The marketing department solution becomes an organizational trap.10

The above problem is very real. As one executive of a large insurance company recognized:

Our corporate marketing department has become an organizational trap. Employees working in various operational departments and account servicing and administration concentrate on handling operations rather than focusing on their customer influencing activities. These customer influencing activities are thought of as being the responsibility of the corporate marketing department. Although these employees realize that they do have responsibility for maintaining customer satisfaction, they tend to focus on the technical aspects of their job. Performance is measured quantitatively and quality is enforced by penalties for mistakes.

If the negative effects of a marketing department are further reinforced by performance measurement systems and reward systems that focus on aspects of jobs other than customer relationship-building and maintenance, the problems increase. In such situations these negative effects are not only psychological, but actual. Concentrating solely on the technical aspects of a job instead of paying attention to customer relationship aspects gives more credit to the employee; the reverse discredits the employee in the eyes of his superiors. Internal efficiency is seen as being more important than external effectiveness and the delivery of good service quality to customers.

In summary, in service organizations it is often counterproductive to introduce marketing departments as the ultimate solution to problems where a market orientation is lacking or insufficient.11 Sometimes they can, however, be used as an intermediate solution. However, there are good examples of firms that have either closed down or drastically reduced the size of their marketing departments and become successful in the marketplace. In a later section of this chapter a case study illustrating such a development is described.

Marketing departments may be helpful for planning, market research and executing corporate-wide campaigns. Customer-influencing activities should, however, be actively planned and implemented as part of the total marketing process in the line organization, where the immediate responsibility lies for rendering service. A marketing department should always be introduced very carefully, so that no one in the organization misunderstands its role. Furthermore, it should never be given a dominant position. If and when such departments are introduced, careful attention should always be paid to the measurement and reward systems used for the part-time marketers outside the marketing department. A marketing department is not an excuse for the rest of the organization to stop being responsible for customers.

ORGANIZING FOR MARKET ORIENTATION: INVERTING THE PYRAMID

A service organization should not be unnecessarily bureaucratic or have a large number of hierarchical levels. Customer orientation requires thoroughly understood and accepted responsibility for customers and the authority to take action to serve them. Large staff with substantial planning and decision-making authority may not have sufficient knowledge and/or the ability to make decisions quickly enough to serve customers well. The organizational hierarchy or pyramid should therefore have as few layers as possible between the customers and top management.

The customer contact personnel create value for customers. The rest of the organization, the back-office functions, management and staff, form a support for buyer–seller interactions in service encounters. This support creates the necessary back-up for the service encounters, i.e. for the successful handling of the numerous moments of truth, such that they become well-utilized moments of opportunity which reinforce the customer relationships.

Management should not be directly involved in operational decision-making on an everyday level, but it should give the strategic support and resources necessary to pursue a service strategy. In a traditional military structure, top management is often far removed from reality. In addition, top management is often surrounded by a staff organization which seals it off from the rest of the organization, including the service encounters and the customers. This, of course, may have a harmful effect on strategic decision-making. Among other things it tends to draw attention away from external effectiveness aspects and make top management overemphasize internal efficiency instead.

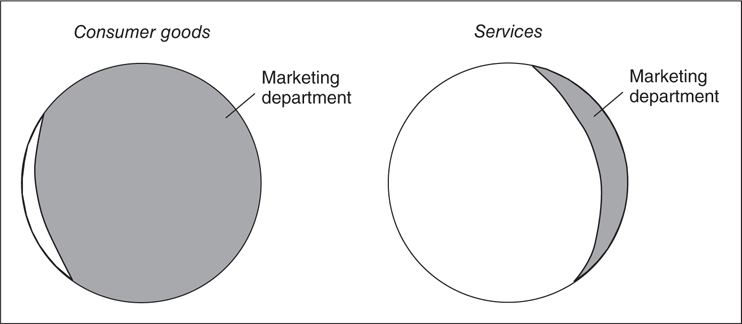

The old traditional view of the organization and the modern service-oriented organizational framework are schematically illustrated as pyramids in Figure 13.3. The transition in organizational thinking, which is the result of a change in strategic thinking according to the principles of service management, means three things. First of all, priorities are changed. This is demonstrated by the fact that the organizational pyramid is turned upside down.12 Top management is not the apex of the pyramid and thus the part of the organizational structure that immediately determines whether the strategy of the firm will be a success or failure. Instead, interactions with customers during service encounters, including personnel, physical resources, information technology and operational systems, are at the top of the organizational hierarchy. The organization’s performance in service encounters determines whether it will be successful and profitable or not. Staff, other support functions and management are a prerequisite for success.

FIGURE 13.3

Service-oriented organizational structure.

Second, the responsibility for customers and for operational decisions is moved from management to staff involved in the service encounters and thus those immediately responsible for the moments of truth. Third, the new thinking means that the organizational pyramid has to be flattened. This follows from the transition of responsibilities and authority to service encounters. Fewer intermediate levels are needed.

THE RELATIVE SIZE OF ORGANIZATIONS

Flattening the organizational pyramid and the decentralization of decision-making authority are necessities if service organizations are to become truly customer-focused. Strategic decisions should be taken by top management at the bottom of the pyramid. Another rule is that decision-making should not be transferred from the service encounters in the pyramid. Some operational decisions have to be taken by middle management, but as much as possible decisions should be taken where the reason for a decision occurs.

It could be argued that a small service firm is frequently more customer-oriented than a big firm. In a smaller organization operational decisions are made more quickly and closer to the customers. It is easier to develop good interactive marketing performance and to provide better functional quality in such situations. Internal marketing is less time-consuming and troublesome. On the other hand, there is more potential strength in large firms. In a bigger firm more resources can be used in order to develop technical quality.

Invisible systems and support functions, to which local branches can easily gain access, can often be developed centrally. This may give economies of scale as well as improve the efficiency of the total service system. It is also sometimes easier to attract better trained people to leading positions in a larger organization, although this is not always the case. Economies of scale can be achieved in production, administration, finance departments and so on, which are invisible to the market.

In summary, one may argue that a growing service firm, in order to remain customer-oriented and be successful, will have to combine the strengths of being a small firm with the strengths of belonging to a large organization. However, there is much evidence that demonstrates that this may be difficult to do. As an organization grows and tries to achieve the advantages of being a large company, far too often it destroys the potential strength of being a small company.

INTERNAL SERVICE PROVIDERS AND INTERNAL CUSTOMERS

Traditionally, customers are thought of as people or organizations external to a company. Such external customers have to be served in such a fashion that their needs are fulfilled and they are satisfied with the firm’s performance. However, there are user-service provider relationships inside an organization as well and also between network partners. The customer contact employees and departments in a firm have to be supported by other people and departments in the firm, if they are to give good service to customers. For example, goods cannot be delivered in a service-oriented way if the warehouse does not supply the truck driver with the correct items, in good condition, and on time.

Every service operation is full of such internal service functions which support one another and the customer contact employees and departments interacting with external customers. Frequently, there may be many more internal service functions than external customer service functions.

To sum up, if internal service is poor, the externally rendered service will be damaged. However, it is often difficult for people involved in internal service functions supporting other departments to realize the importance of their performance to the final service quality. They rarely see ‘real’ customers, and they can easily feel that those whom they serve internally are somehow just fellow employees and that the service they get does not affect external performance in any way.

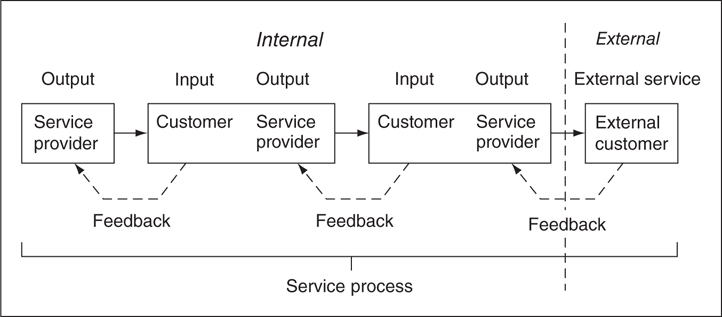

A way of tackling the attitudinal problem of those who should serve ‘somebody else’ (other than the ultimate customers) is to introduce the concept of internal customers.13 This concept brings customer–service provider relationships inside the organization, as illustrated by Figure 13.4. There may be one or a whole range of internal service functions, each illustrated by a box within the larger box in the figure. These functions are internal customers to other internal service providers; they are also service providers to other internal customers. Finally, in the service process, the ultimate output is the external service received and perceived by the ultimate external customer. In a network context or in a virtual organizational constellation, the difference between what is internal and what is external becomes blurred. However, the same type of service provider–internal customer chains exist and have to be managed in the same customer-oriented manner, so that the final, ultimate external customer receives good service.

When the existence and importance of internal customer relationships are realized by personnel, it is much easier to change attitudes among employees. The concept of internal customers gives a totally new dimension to the tasks performed inside an organization. It is more easily realized that ‘a satisfied customer’ should not only refer to individuals or organizations external to the firm.

Sometimes the internal customer–service provider relationships may be straightforward. However, frequently they can be complicated, with relationships in which both parties serve each other, or when the outcome of one department depends on the internal service provided by two or more other departments. It is mandatory that such internal customers are served as well as external customers are expected to be served. This means that generating quality into service is not the exclusive duty of departments visible to external customers. For example, the perceived quality of delivery service depends just as much on the performance of the warehouse as it does on the performance of the delivery function. Therefore, the responsibility for producing good service quality is spread throughout the organization as well as in a network of co-operating organizations throughout the network.

FIGURE 13.4

Internal service functions and internal customers.

In many cases two or more departments may be directly involved with customers. Then it is of vital importance that these parallel processes are co-ordinated and perceived by customers as one single service process, otherwise service quality will deteriorate. If there is no one responsible for the customer in such situations, the customer may be sent from one person to another in a disorganized way. The organization does not take responsibility for the service, and the customer is forced to take over the responsibility for getting service. This is bad quality.

The service production process is built up by interrelationships and interdependencies between a number of sub-processes. The external customer only gets in touch with part of a company’s subsystems. There is a line of visibility14 dividing those parts of the process that customers immediately see and perceive from those parts that only indirectly influence the service quality perception. Psychologically, this sometimes causes internal problems. Because in many cases these interdependencies between internal service providers and internal customers are not discussed and stressed enough by management, this is often understandable. However, almost all employees have customers to serve, although many customers may be internal ones.

When developing a service production system, various strategies can again be used. The part of the total system that is on the visible side of the line can be limited to, say, only one or two persons. Customers only contact them, and most of the service production process is taken care of internally. For example, an insurance company that directs all of its contacts through one single agent uses such a strategy. Such a strategy is applied, of course, to make it as easy as possible for customers to deal with the firm. In other situations the visible side of the line consists of a system or physical resource only, as in Internet shopping where the customer interacts with a website. Another strategy is to expose customers to many sub-processes. A restaurant, for instance, is normally forced to apply such a strategic approach. In this case the customer relationship is broader and more vulnerable. Mistakes that may occur do so under the eyes of the customer. Fewer problems can be taken care of as internal affairs. Of course, there are an unlimited number of options between these two examples. The main thing is that the service production process is designed so that perceived service quality can be monitored and kept at an intended level. The daily activities and processes, the needs and wishes of target customers should guide strategic decisions concerning where the line of visibility is drawn.

WHERE IS MARKETING IN THE ORGANIZATION?

To conclude the discussion about organizational structures, it is appropriate to ask: ‘Where is marketing in the organization?’ As marketing is what a firm does to get customers and to keep and grow customers on a profitable basis, i.e. marketing is what relates a firm to its customers and what makes it possible for the firm to engage with its customers’ processes, there is only one logical answer to this question:

Marketing is definitely not only carried out in a marketing department of full-time marketing specialists. Marketing is everywhere in the organization, wherever brand contacts occur and wherever the customers’ quality perception is formed as a basis for their willingness to continue their relationship with the service provider. Marketing is also wherever internal customers are served in internal back-office operations.

Because marketing is everywhere and is the responsibility of no one single department, there is an obvious risk that in the end marketing is nowhere and nobody takes responsibility for it, and consequently that no one takes responsibility for customer focus in the organization either. Indeed, service providers in practice often establish separate functionalistic marketing departments to take care of the marketing process, so that they can see where marketing is concentrated. Soon enough they realize that this does not work. Marketing is everywhere in the sense that there has to be a marketing aspect in all roles, tasks and departments of a service organization; a customer focus throughout the organization. In other words there has to be an appreciation of the customer in all tasks that are performed in the organization. Part-time marketers can be found in operations, finance, administration, logistics, research and development, human resource management, and all other departments. Furthermore, technology and systems that have an interactive marketing impact are also all around the organization and should be treated as part-time marketing resources, for example, when investment decisions are made.

Of course, service providers also need someone who takes responsibility for market research, planned marketing communication (to the extent this is needed), pricing issues and other traditional marketing activities. Therefore, most service organizations need some full-time marketers to take care of the traditional external marketing processes. Full-time marketers should also be instrumental in internal marketing processes, normally working closely with human resource management. However, to organize them into a ‘marketing department’ may be detrimental and ineffective. Such a department can make promises, and can do so effectively, but it cannot contribute to the fulfilment of promises. Finally, the better the organization takes care of its customers and provides them with good service quality and value support, the less work there is for full-time marketers.

The only person who can be responsible for the total marketing process is the CEO or managing director, or locally the regional director, and more locally the outlet/branch manager. A marketing manager who is responsible for a department of full-time marketers can only be responsible for this department. However, a marketing manager is a customer specialist and should have an active role in the total marketing process as an internal consultant to top management.

Another conclusion to be drawn is that marketing cannot be totally organized in a service firm. Marketing can only be instilled in the organization. However, it has to be systematized in some way. Here are a few guidelines:

Instilling a marketing attitude of mind in people in all departments and enabling customer-focused performance as well as supervisory and reward systems that reinforce such performance is one aspect of how to organize marketing in a service firm.

Clarifying the responsibility for the customer of top management and all line managers is another aspect of marketing.

The service provider may of course also need to use traditional external marketing efforts to some extent, and to do market research. Therefore, resources for doing this internally and/or externally should be secured. Many traditional marketing activities can be taken care of by the local line organization, but a central marketing group or staff with full-time marketers may be required as well.

It is important to make sure that this central group does not become a dominant marketing department that psychologically has a negative effect on the customer focus of employees in other departments and functions.

Full-time marketers have an important role in the marketing process, but it is the part-time marketers and the interactive marketing process that are at the heart of marketing in service organizations.

In conclusion, when organizing marketing in a service firm the following should be kept in mind:

• Successful marketing requires a marketing attitude of mind throughout the organization, because the central part of marketing takes place in the service encounters, and in back-office support to service encounters, through customer-oriented part-time marketers and service-oriented systems and technologies (the interactive marketing process).

• Responsibility for marketing lies within the line organization, and the managing director has to accept the ultimate responsibility for marketing.

• Many of the traditional external marketing activities that may be needed can be handled locally in the line organization, but a central marketing staff of full-time marketers may sometimes also be required to take responsibility for centrally implemented marketing activities as well as to act as internal consultants to top management in customer-related issues and in internal marketing.

The aim of installing marketing as such a holistic concept in an organization is, of course, to make a firm customer-centric, where the management mindset as well as the planning and execution of service processes are customer-focused. The ultimate goal is to gear the firm’s management approach from inside-out management to outside-in management (see Chapter 1).15

The following sections of this chapter look more closely at what one needs to know about customers, and at the service process, and discusses how the latter can be developed so that a good interactive marketing effect can be achieved.

WHAT DO WE NEED TO KNOW ABOUT OUR CUSTOMERS?

What makes a given customer want a certain type of service? What makes the customer purchase it from a certain service provider? The reactions of customers are based on their expectations, but these are a function of a whole range of internal and external factors.

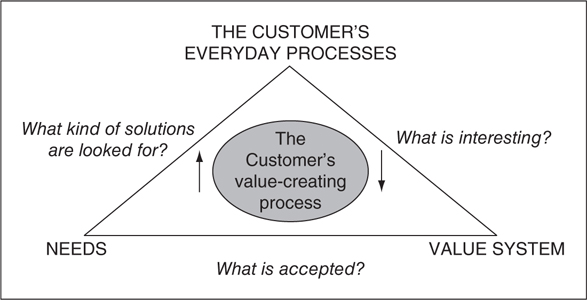

First of all, the service provided by goods or service activities purchased has to fit the customer’s value-creating processes, so that it supports value creation in his everyday activities and processes (or those in the organization he represents). For example, a firm that looks for a sales supporting database system wants a solution that makes it possible to easily find out, save, change and retrieve information about customers in order for the sales representatives to develop an understanding of the needs, values and internal processes of customers and offer them service that suit their needs. Any solution that does not fit this process will not interest the firm, because it will not create the value they want. Customers’ everyday activities and their value-creating processes are the most important thing for a firm to know about its customers, if possible on an individual basis, otherwise on a segment-by-segment basis.

It is, however, essential to realize that the value-creation processes alone do not determine what kind of service a person looks for. Many service providers can usually produce an acceptable solution that could offer adequate support to a customer’s value generation. In addition, customers also have certain wishes in relation to how they want the service provider to treat them. This normally narrows the scope of options available. For example, almost any retailing bank can provide an individual with banking service, but not every bank manages to treat customers in a way they are pleased with (compare the technical and functional dimensions of customer perceived service quality). This is also related to the customer’s value system, which determines what kinds of solutions to a problem are considered acceptable and what is considered out of the question. Environmental concerns are examples of aspects in the value system that exclude some otherwise possible need-satisfying solutions. Some consumers do not want to use cosmetics that have been developed using animal testing, and they will not buy such products. In conclusion, a customer’s everyday processes, in combination with his value system, determine what kind of solutions are of interest to him.

The needs of a customer follow from his value-creation process and how he wants his values to be supported. They direct expectations towards a certain type of solution. An organization may form its needs in a more complicated way than a single customer or a household. In principle, however, an organization’s or a person’s need is some sort of a problem that requires a solution. This solution may be solved in a number of ways. For example, house cleaning can be managed by buying proper equipment and by a do-it-yourself approach, or one can take care of it by purchasing a service. In both cases there are a number of options available in relation to what to buy, and where to buy the necessary equipment or service. A customer’s needs, combined with his value system, determine what kind of solutions or offerings are acceptable to him. Finally, a customer’s everyday processes and his perceptions of his needs determine what kind of solutions he is looking for. This could be labelled the customer’s game plan.

To sum up, in order to thoroughly understand customers and potential customers the marketer needs to acquire information about the following (see Figure 13.5):

• The customers’ everyday processes and value-creating processes.

• The customers’ value systems.

• The customers’ needs that follow from their value-creating processes and value systems.

Traditionally, customer needs are the main focus of market research. Such studies are still important, but today it is even more crucial to develop a thorough understanding of customers’ everyday processes which influence their value creation. It is also more or less impossible to market anything to customers that violates their value system. However, the most important task for market research today is to study the customers’ everyday processes and what kind of solutions would support them in a value-creating way. Today, firms normally know the least about such everyday processes, what customers are doing in their everyday lives, and why, and what they are trying to achieve, or what they would like to achieve. Much more research about these issues is needed. Here, traditional methods are of limited value. Instead various ethnographic methods should be used, where the researcher in various ways gets close to the customers (‘lives with the customers’) and tries to understand what they are doing, why and for what purpose.

FIGURE 13.5

The customer’s gameplan: what do we need to know about the customer?

Customers’ needs, wishes, value systems and value-creating processes are of vital importance for the development of customer expectations. However, expectations are also formed by external factors (this was discussed in more detail in previous chapters). For example, what family acquaintances and business associates say about a given service provider (word-of-mouth communication) has an impact on the formation of the expectations as well as what newspapers and trade magazines write about the service firm and its service and what is discussed in social media. This is often of great importance. Moreover, planned marketing communication activities, such as personal selling and advertising campaigns, influence expectations. Finally, the overall company image and local image also influence expectations.

CUSTOMER SEGMENTS AND TARGET GROUPS

Customers have differing needs and/or wishes about how they want to be treated. An organization can, therefore, very seldom satisfy the needs of every potential customer in a similar manner. It should not even try to solve everyone’s problems or support everyone’s value-creating processes. Customers have to be divided into homogeneous segments, which are sufficiently different from each other. One or a few such segments are then chosen as target groups of customers. In service contexts it is often difficult to satisfy target groups of customers with too widely varying needs and wishes. Because customers frequently meet and interact with each other, they influence fellow customers’ perception of the service. For example, a family having a picnic on a Saturday afternoon in the park does not mix well with a bunch of beer drinkers. If the firm goes for segments that are very different from each other, it is usually a good idea to keep them apart. Finally, it should be observed that a service production system cannot usually take care of satisfying too diverse needs and wishes. This follows from the fact that service is a complicated phenomenon and service production is a complicated task.

It is also important to remember that customers in a relationship with a service provider often want to be recognized and treated as individuals, even though they are part of a larger segment. Therefore, the firm should not be blinded by the fact that it may have mass markets and may use the segment concept for analytical purposes. Customers often want to be treated as segments of one.16 Direct customer contacts occur naturally in most service contexts and they give a good starting point for the individual treatment of customers. In addition, the information technology available to firms today also supports individualistic treatment of customers.

RELATING THE SERVICE PACKAGE TO THE CONSUMPTION PROCESS

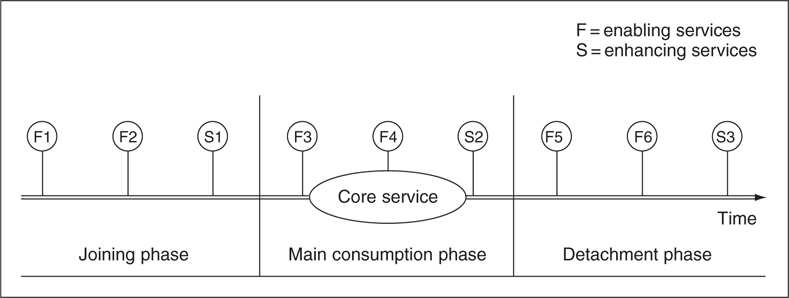

We now turn to the issue of how the customer and the consumption process can be incorporated into the service process. Doing this is of utmost importance because of the nature of service and the inseparability of large and critical parts of production and consumption. The service consumption process can be divided into three phases:17

Joining phase.

Main consumption phase.

Detachment phase.

The joining phase is the first stage of the consumption process, where the customer gets in touch with the service provider in order to buy and consume a core service, for example, elevator maintenance. In this phase facilitating services are mainly required, for example, telephone contact with the elevator maintenance firm in order to get hold of a service technician. Some enhancing services may be used, for example a toll-free number or an easy-to-use website, which makes it easy for the customer to get in touch with the maintenance firm. A customer’s perception of service quality and his value creation start already during this phase.

The main consumption phase is the main stage of the total service consumption process. In this phase the needs of the customer have to be satisfied, and his value-creating process has to be supported.

Hence, the core service is consumed at this stage. For example, the elevator is serviced. Furthermore, there may be some enabling services (for example, a shelter surrounding the work space) and enhancing services (for example, instructions to people normally using the elevator directing them to the stairs and telling them when the job is expected to be finished). In the detachment phase the customer leaves the service process. This often requires some enabling services (for example, the service technician fills in a report and hands it over to the caretaker or another representative of the customer). Enhancing services may be used here, too. It is important to realize that this phase also contributes to the customers’ perception of service quality and supports their value creation. Because the detachment phase includes the customers’ final experiences with the service, what happens during this phase may be especially important for them and their quality perception.

FIGURE 13.6

The service package and the service consumption process.

Source: Lehtinen, J., Quality Oriented Services Marketing. University of Tampere, Finland, 1986, p. 38. Reproduced by permission of Tampere University Press.

In Figure 13.6 the service consumption process and the types of services related to the three phases of the process are illustrated schematically. If, for example, we look at a full-service restaurant, the joining phase may include table reservations (F1) and cloakroom services (F2) as enabling services, and valet parking (S1) as an enhancing service. During the main consumption phase the core service, which may be a three-course dinner, is consumed. The table setting (F3) and the performance of the waiting staff (F4) are enabling services, and live music (S2) may be an enhancing service. In the detachment phase, when the customer leaves the restaurant, some enabling services are needed, for example, paying the bill (F5) and again the cloakroom services (F6). Valet parking (S3) may be used as an enhancing service again at this stage. Depending on how the enabling services function, they may operate in a service enhancing manner as well.

It should be observed, however, that this model only takes into account the components of the basic service package (core service as well as enabling and enhancing services and goods). The next step is to take the components of the augmented service offering (see Chapter 7); that is, accessibility, interactions and customer participation, into account so that the functional quality dimension of the process is also covered.

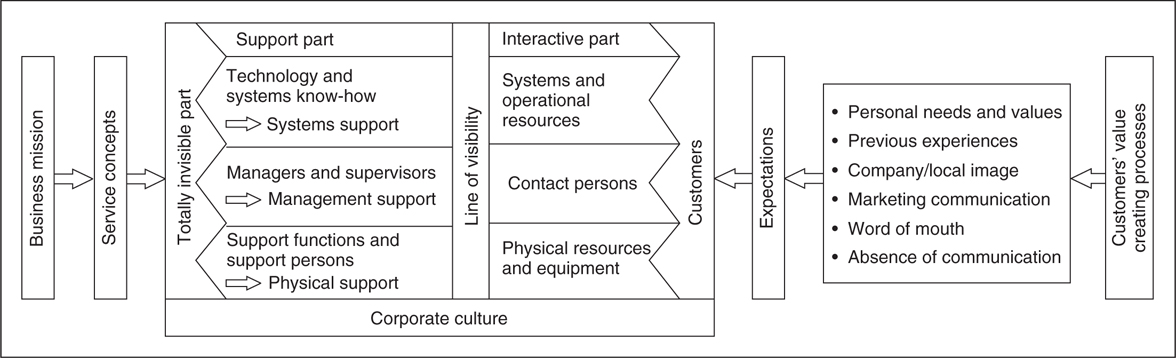

THE SERVICE SYSTEM MODEL

The service system model illustrated in Figure 13.7 can be used for analysing and planning the service process.18 In this figure the various quality-generating resources are combined in a systematic way. The large central square illustrates the service-producing organization from the customer’s perspective. From the producer’s point of view there may be several functions or departments involved, but the customer sees it as one integrated process or system. The customer is located inside the square because he is a resource participating in the service process and therefore an integral part of the service system model. Yet, in most service processes, customers are treated as an outside factor only. This, of course, is due to a manufacturing-oriented view of the role of the customer. However, they are inside the organization and interact with parts of the organization in the service process and are a service production resource.

FIGURE 13.7

The service system model.

The line of visibility divides the part of the organization that is visible to customers from the part that is invisible. To the right, outside the main square, the means of influencing the expectations of customers are illustrated, such as their needs and wishes, their previous experiences, overall company and local image, word of mouth and social media, external planned marketing communication and absence of communication.

To the left of the square are the business mission and the corresponding service concepts which, like umbrellas, should guide planning and managing the service system. At the bottom of the main square is the corporate culture; that is, the shared values that determine what people in the organization think and appreciate. This culture is always present. Sometimes it has a substantial impact on the employees, sometimes it is more vague. If the culture is not service-oriented, it creates problems for an organization providing service. This issue will be returned to later in Chapter 15.

THE INTERACTIVE PART

The visible or interactive part of the service system model (see Figure 13.7) corresponds to the service encounter where the customer meets the service organization. It consists of customers and the rest of the quality-supporting resources that the customers interact with directly. Here the moments of truth take place. The quality-supporting resources in the interactive part are as follows:

• Customers involved in the process.

• Customer contact employees.

• Systems and operational routines.

• Physical resources and equipment.

Customers are directly involved in the service system as co-producers. Because of the nature of service production and consumption, customers are not simply passive consumers. At the same time they consume the service, they also take part in production of that service in an active way; sometimes more (as when at the hairdresser’s or having a three-course dinner at a gourmet restaurant), sometimes less (as when using a freight forwarder’s service). In some cases customers interact with a large service system when staying at a hotel, but in other situations they are in touch with only a limited sub-system, as when operating an automatic teller machine. Sometimes several customers are present simultaneously in the process interacting with each other. In other situations, as in the case of telephone communication, the service concept is to provide technology and a system that makes it possible for customers to contact each other. Irrespective of the nature of the situation, customers, however, actively take part in the process and in service production. It is important to analyse how customers influence the service process, and to avoid situations where they have a negative impact on the process, and on the behaviour of service employees and the effectiveness of systems used in the process. One must be aware of the fact that sometimes a firm has misbehaving customers, and that there is a readiness in the firm to handle such customers. Furthermore, service processes are sometimes designed in a way which triggers customer misbehaviour.19

Customer contact persons are employees directly interacting with the customers. Sometimes they are also called ‘service employees’ or ‘frontline employees’. Anyone can be a contact person, irrespective of which position or job he may have in the hierarchy. Interactions that take place may be face-to-face contacts or interactions over the telephone or even by e-mail, fax or letter. A manager or supervisor may also be a contact person if direct customer contacts, on a regular or irregular basis, are part of his job. Frequently, contact personnel are the most crucial resource for a service provider. Systems, technology and physical resources are a valuable support, but most service organizations depend more on their contact staff than on other resources. Contact persons are in a position to recognize the wishes and demands of customers in the moments of truth by watching, asking questions and responding to the customers’ wishes, worries and behaviour. Furthermore, they are able to instantly follow up on the quality of the service rendered and undertake corrective action as soon as a problem is observed. However, more and more service processes are designed so that no contact persons are present, at least not on a regular basis. This makes the process more vulnerable when service failures occur.

Systems and routines consist of all operational and administrative systems as well as work routines of the organization. Queuing systems, call centre systems, how to cash a cheque in a bank, how to operate a vending machine or how to make purchases on a website are examples of such systems. There are a vast number of systems and routines that influence the way of consuming the service and performing various tasks. The systems can be more or less service-focused. A complicated document that customers are supposed to fill in forms a system that is not service-focused. This normally means that the perceived service quality is poorer than it otherwise would be. A manufacturer of goods has a range of such systems, which may be performed as administrative tasks without taking the customer into account or turned into service-focused processes. Such systems include research and development, the installation of machines and equipment, deliveries, customer training, quality control at the customer’s premises, claims handling, billing or the service of a telephone receptionist.

These systems and routines have a double impact on service quality. First, they directly influence the quality perception of customers, because customers have to interact with systems. If they feel comfortable with a certain system, it is probably service-oriented. If they feel that they are forced to adjust to a system, however, there is room for improvement. Quality is destroyed or damaged by the system. Second, the systems and routines have an internal impact on employees. If a certain system is considered old-fashioned, complicated or not service-focused, employees who have to live with the system will get frustrated. This, of course, influences motivation in a negative way.

Physical resources and equipment include all kinds of resources used in the service system. Computers, documents and tools belong to this category. Some of these physical resources are a prerequisite for the good technical quality of the output. However, they also influence functional quality because customers may find it more or less easy to use them in self-service tasks and they make a favourable or less favourable impression on customers. Other physical resources only have an impact on functional quality. The interior of waiting rooms is an example of such physical resources. Physical resources and equipment used in the service process have an internal effect on employees similar to that of the systems. Physical resources and equipment form the servicescape20 of the service process, where customers, contact persons and systems and resources work together. The servicescape can also include objects, music and even aromas that support a positive perception of the ambience and physical elements of the service encounter. All these elements form the visible part of the service process. Every single part, including the customers, has to match the total system if good quality is to be perceived.

THE IMPACT OF THE SUPPORT PART

Behind the interactive part, where the customer directly encounters the service organization, there is the line of visibility (see Figure 13.7). Customers seldom see what is going on behind this line, and they often do not realize the importance of the service production that takes place there. This causes at least two types of problems for the service provider. First, what takes place behind the line is not always appreciated as much as it should be by customers. Because of this, customers do not realize how much the service production there contributes to service quality and value support. Irrespective of whether good quality, especially good technical quality, is produced here, customers probably perceive a bad service quality if the interactive part adds mediocre or worse quality. What often happens is that good technical quality produced behind the line of visibility is damaged by bad functional quality produced in the service system in front of this line. On the other hand, good service intentions by contact persons can also be hindered by low-quality support from back offices.

Second, customers may not understand why a given service has a certain price, because they do not realize how much is done behind the line of visibility. It may be difficult to explain why the price is so high, when the visible service production process may seem uncomplicated and therefore in the minds of customers should not justify the high price level.

The service provider, on the other hand, may interpret the importance of the supporting back office in another way that is equally wrong. Because the service provider knows how much of the total value support is produced in the back office invisible to customers, he can assume that customers also know and appreciate this, and consequently enough attention is not paid to the customer orientation of the visible and interactive part of the service process. This may turn out to be a serious mistake.

COMPONENTS OF THE SERVICE SYSTEM BEHIND THE LINE OF VISIBILITY

What happens in the supporting and invisible part of the organization has an impact on what can be accomplished by the interactive part. This support is sometimes a major prerequisite for good service. There are three kinds of support to the interactive service production (see Figure 13.7):

Management support.

Physical support.

Systems support.

The most important type of support is management support, which every manager and supervisor should provide to their staff. Managers and supervisors maintain corporate culture, and if the firm wishes to be characterized by a service culture, they will have to support the values of such a culture. They are responsible for shared values and ways of thinking and performing in their work groups, teams and departments. If employees are to be expected to maintain service-focused attitudes and behaviours, managers are the key to success. The manager is the leader of the troop. If the boss does not provide his team with a good example, and if he by his leadership is not capable of encouraging them to be service-minded and customer-conscious, the organization’s interest in its customers and in giving good service will decrease. From this follows deteriorating functional quality of the service production process and perhaps even difficulties in maintaining the technical quality of the outcome of the process.

Contact personnel often have to rely on physical support provided by functions and departments invisible to the customers. These support employees have to consider customer contact personnel as their internal customers. In the supporting part there may be a range of support functions, for example, behind each other as discussed previously in this chapter. Support staff have to be treated as internal customers by support functions further behind in the service system. Internal service has to be as good as the service to ultimate customers, otherwise the perceived service quality will be damaged. Calculating background data for offering an insurance policy and loading trucks in warehouses are examples of physical support.

The third type of support is systems support. This is of a somewhat different nature. Investments in technology, for example, computer systems, information technology, buildings, offices, vehicles, tools, equipment and documents, form the systems support from behind the line of visibility. If the organization invests in an unreliable, slow computer system that does not permit prompt answers to customers’ questions or rapid decision-making or that regularly crashes, or a database that does not provide contact personnel with easily and quickly retrievable information about customers, the service system lacks good systems support. If a contact person cannot provide good service because of existing management regulations, there may be another type of inadequate system support – rules and regulations that are too rigid.

There is also another kind of systems support. The knowledge employees have of operating various systems is systems know-how. The organization must invest in employees who know how to operate and make best use of the company’s systems and technology, and should provide training.

Behind the support part is the totally invisible part of the organization. This part is in a way outside the service system. It consists of functions that do not influence the service offering or service quality, either directly or indirectly. Internal bookkeeping is an example. Frequently, analysing an organization shows that there are surprisingly few parts that are totally invisible.

THE BLUEPRINTING MODEL

Service blueprinting is a well-known model of planning the service process as a system. The model was originally introduced by Lynn Shostack.21 During the past few years this planning model has been used extensively.22 In the blueprinting model sub-processes and activities in a service process are depicted and the relationship between them is established and related to the customer’s contact points with the various processes. In this way the interrelationships between activities in the interactive part of the service process in front of a line of visibility and activities in a supportive back office behind this line are established, and a blueprint of the whole process is developed. In this way it is possible to analyse how a service process can best be designed to support good customer perceived service quality.

THE SERVICE PROCESS LANDSCAPE: THE SERVICESCAPE AND THE EXTENDED SERVICESCAPE MODEL

The service process and the service encounter take place in an environment that is partly planned and controlled by the service provider. External environmental conditions, such as the weather and competitors’ actions, are not under the firm’s control and in some situations the service is provided in the customer’s premises. However, in most cases the immediate environment in which the service process takes place can be, and should be, carefully designed and developed by the firm. Otherwise, the number of uncontrolled factors grows. In order to help service organizations manage the physical setting of the environment for the service process, Bitner introduced the servicescape model.23 When presenting the model she also makes the point that ‘interestingly, in service organizations the same physical setting that communicates with and influences customers may affect employees of the firm’.24

THE SERVICESCAPE FRAMEWORK

The servicescape framework is based on the idea of a landscape for the service process. In this landscape the service encounters take place and the service contact personnel and the customers interact during the service process. However, according to the framework, customers and employees are not part of the service landscape, but their behaviour is influenced by it. The model has been criticized on this very point, that it does not – as integral parts – include the people acting in the physical setting. According to this criticism the physical setting is formed by the people who are in this setting and act and interact in it.25 Moreover, the servicescape framework has been criticized on the grounds that it fulfils an instrumental role only,26 and it excludes people’s cultural perception and their experiences,27 behavioural intentions when entering the physical setting for the service encounter28 and social interactions.29

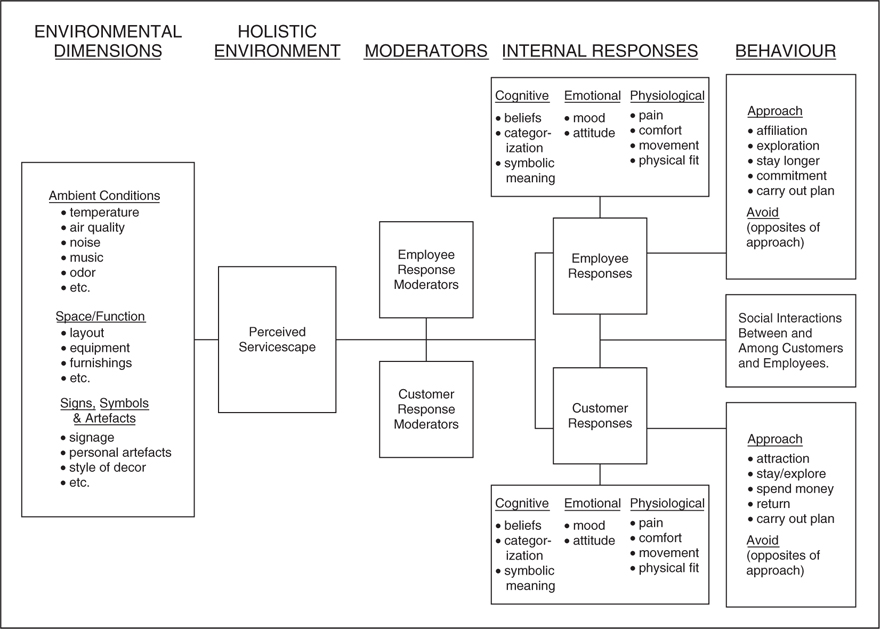

In spite of this criticism, the servicescape model provides a basic model for understanding the physical setting of a service and its influence on employees and customers. The model is illustrated in Figure 13.8.

The servicescape framework in Figure 13.8 is fairly self-explanatory. Hence, it will be commented upon only briefly here. The elements or typology of the framework are three environmental dimensions – that is, ambient conditions (temperature, air quality, music, noise, odour, etc.), space and function (layout, equipment, furnishings, etc.) and signs, symbols and artefacts (signage, style of décor, etc.) – the perceived servicescape as a holistic environment, moderators that affect employee and customer responses, respectively, three internal response factors (cognitive, emotional and physiological – see the figure for details that impact employee and customer responses, respectively), and behaviour. A behavioural element is, of course, the social interaction among employees and customers. However, because it has an instrumental influence on these social interactions, a main effect of the servicescape framework is the way people react to the physical setting. The framework includes two opposite ways of reacting: approach (affiliation, exploration, stay longer, commitment, carry out plan) and avoid (defined as the opposite of approach).

The servicescape model is certainly helpful for designing the physical setting of a service process and service encounters, and it indicates what factors could be observed when assessing the effectiveness of such a physical setting. However, as the criticism of the framework pointed out previously indicates, to explain the interactions between the customer and employees and other resources in the setting, it may be too structured and the social and behavioural context is lacking.

FIGURE 13.8

The servicescape model.

Source: Bitner, M.J., Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(Apr); 1992: p. 60. Reproduced by permission of the American Marketing Association.

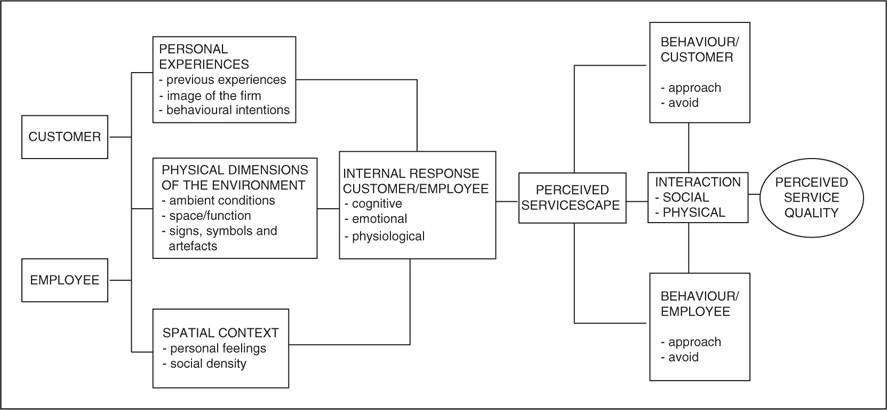

THE EXTENDED SERVICESCAPE MODEL

In Figure 13.9 an extended servicescape model is illustrated. This extended model attempts to include aspects of the physical setting as a social meeting place that are lacking in the original framework.30 For the sake of readability, the detailed factors that are similar to the ones in the original servicescape framework are not explicitly listed in the figure. The reader may want to consult Figure 13.8 (the original framework).

FIGURE 13.9

The extended servicescape model.

Source: Sandbacka, L., Tjänstelandskap. Teoretisk bakgrund och praktisk tillämpning i tjänste Företag, (Servicescape. Theoretical background and implementation in practice.) Helsinki: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland, 2006. Reproduced by permission.

Customers and service employees are both part of the extended servicescape framework; by their presence and behaviour at the same time as they are affected by the physical setting of the service, they also form it. Perceived service quality is included as the final outcome of the model. The physical setting and the interactions taking place in it should be designed so that, in the final analysis, customers perceive favourable service quality that makes them want to continue using the same service provider’s offerings. Moreover, not only social interactions between people in the servicescape but also interactions with the elements of the physical setting itself are included in the framework (physical interactions). Customers, and employees, do not only interact with each other but also with physical resources, systems and other tangible elements in the physical setting. Hence, in addition to the social interactions these physical interactions influence the customers’ perception of service quality. At the same time, the customer contact employees also perceive such physical interactions and, in addition to the social interactions with customers, these interactions affect them as well. Both the social and physical interactions affect their feeling of well-being as well as their motivation to be customer focused, and their proneness to provide customers with good service and in the end good service quality.

To the physical dimensions of the service environment, such as ambient condition, space, signs, symbols and artefacts (see Figure 13.8 for details), two factors influencing the servicescape have been added – personal experiences and spatial context. The customers as well as the employees bring their previous experiences from the physical setting at hand and other servicescapes, their image of the service provider and their behavioural intentions to the service process. All this affects the perceived servicescape and therefore also their behaviour in it. In addition, the spatial context of the physical setting has to be taken into account. The number of people, fellow customers and also employees in the environment, i.e. the social density, and the personal feelings towards the type of spatial context they become involved in also influence the customers’, and employees’, perception of the servicescape.

As in the original model the internal responses of customers and employees are cognitive, emotional and physiological (see Figure 13.8 for details). From these responses the perceived servicescape emerges. Customers and employees interact socially and with the physical elements of the servicescape and their behaviour in the servicescape can be characterized either as approach or avoid behaviour (see Figure 13.8 for details). Finally, a customers’ perception of service quality is formed.

In conclusion, the extended servicescape model brings the social context including personal experiences and the spatial context as well as both customers’ and employees’ interactions with the physical setting into the framework. Moreover, it explicitly points out that the ultimate goal for the customers’ and employees’ either approach or avoid behaviour in the physical setting, and the social and physical interactions taking place in it, is to create favourable perceived service quality for the service provider’s customers. Alone and especially together with the service system model in Figure 13.7, the extended servicescape model provides a useful framework for planning service processes. Together with the service style/consumption style model presented in the next section (see Figure 13.10), they form a comprehensive framework for planning service encounters and buyer–seller interactions, and therefore also for planning the service organization’s interactive marketing process.

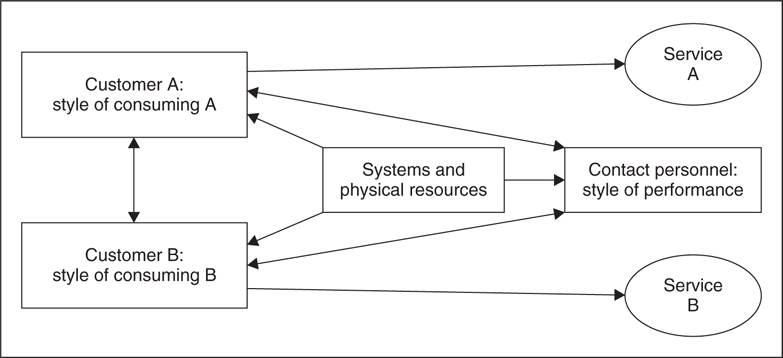

FITTING RESOURCES IN THE SERVICE SYSTEM TO THE SERVICE CONSUMPTION PROCESS

The quality-supporting resources – personnel, systems, goods, technologies and physical resources, and customers – have to be carefully planned so that a competitive functional quality is produced in the service process. If good quality is produced, an excellent interactive marketing impact is also created. In Figure 13.10 the nature of this issue is illustrated schematically.

FIGURE 13.10

The service style/consumption style model.

Source: Lehtinen, J., Asiakasohjautuva palveluyritys (Customer-oriented service firm). Espoo, Finland: Weilin+Göös, 1983, p. 81.

The model demonstrates the need for achieving a balance between the resources involved. In the service encounter and its moments of truth, contact personnel emerge as one critical resource. Every contact person has a specific way of performing, which can be called their service style or style of performance.31 For example, a dental receptionist and a dentist have their own way of doing and saying things and of performing their tasks. This style is, of course, partly due to their professional skills, but partly also due to their attitude towards patients.

This style of performance has to be geared to the corresponding style of consuming of the customers, here the dentist’s patients. If there is a misfit between these two styles, perceived service quality will probably be damaged. Since many different customers are frequently present at the same time, their styles of consuming must also fit. For example, a nervous patient in the waiting room may scare other people waiting to see the dentist. In a restaurant, a group of people drinking beer and a family having lunch may not get along well in the same servicescape. The perceived service quality deteriorates.

The systems and physical resources used in the service production process will also have to fit the style of performance of contact staff as well as customers’ style of consuming. Inappropriate systems make this unnecessarily complicated and even frustrating for contact persons to do their job. Also, if there is a misfit between the systems and the customers’ style of consuming, they will not want to adjust to the systems and they will find it awkward to take part in the process. The perceived service quality is again damaged. For example, the treatment procedures and the equipment of the dentist, as well as registration and recall systems and waiting room facilities, have to fit the dentist and the other contact persons as well as the patient. The circles ‘Service A’ and ‘Service B’ in Figure 13.10 indicate that Customers A and B may perceive slightly different service, irrespective of whether or not the basic service package is the same. In conclusion, the availability of quality-generating resources as such does not automatically lead to good customer perceived service quality. Sufficient and properly designed resources are a prerequisite, whereas the fit between them determines success.

Figure 13.10 illustrates a case involving external customers. The same applies for internal customers too. The style of performance of supporting staff will have to match the style of consuming of contact staff as internal customers. If there is a misfit, the internal climate will suffer and contact personnel will feel that they get bad support – that is, insufficient internal service – from the support function. Moreover, the systems and physical resources of the support function will have to fit into the service process in a similar manner.

THE SERVICE SYSTEM IN A NETWORK OF SYSTEMS

In previous sections the service system model has been viewed as a single organizational unit. This is, of course, not always the case. Frequently a total system is built up through a network of separate service systems. This, in the minds of customers, is normally perceived as one service system.32

For example, a hotel chain may have a hotel reservation system, which is geographically located away from the hotels. Customers who make their reservations themselves through this system on one date and stay at a hotel at a later date judge the two service processes (the reservation system and the hotel’s service production system) separately, but they also view the reservation system as a part of the hotel’s system. If the reservation system fails, the customer will not make a reservation at the hotel, and consequently, the total service process system (reservation and hotel together) fails. In principle, the same holds true if the customer makes his reservation through a travel agent not affiliated with the hotel chain. From a management point of view, it will probably be more complicated to manage the total service system, since the other system of this network, reservation through an independent travel agent, is an independently managed organization.

Sometimes the situation becomes even more complicated because the relationships between the parties in a network are often mutual. In the previous case, the hotel’s service system depends on that of the travel agent. But the service system of the latter also depends on that of the hotel. If the travel agent directs a customer to a hotel that turns out to be unsatisfactory, the customer will blame not only the hotel but also the travel agent. In this situation the travel agent can be considered a subcontractor of the hotel. However, they are both part of a network that consists of the service systems of both parties, and the customer will judge not only the systems of the two parties separately, but the total service system of the network.

In manufacturing, firms often outsource various service activities to sub-contractors. For example, independent delivery firms transport goods to customers, and independent firms are used to handle installation, technical service and repair and customer training. In these situations, similar networks to those above emerge, where the manufacturer is often judged by the performance of the service system of its subcontractor.

From a management point of view, it is essential to observe the existence of these networks of independent or affiliated service systems, and to realize the impact of one system on another and on the success of the total system. For example, bad performance by one party, say an insurance broker, in the network may damage, or even destroy, the other party, in this case the insurance company. On the other hand, excellent service provided by a partner in the network, say, by a delivery and transportation firm, may substantially enhance the image of the manufacturer in the minds of its customers.

NOTES

1. In the 1980s, Haller and Piercy predicted that marketing as a separate function and marketing departments as organizational solutions would disappear. See Haller, T., Strategic planning: key to corporate power for marketers. Marketing Times, No. 2, 1980 and Piercy, N.F., Marketing Organization. An Analysis of Information Processing, Power and Politics. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1985.

2. See, for example, Gummesson, E., The marketing of professional services – an organizational dilemma. European Journal of Marketing, 13(5), 1979; Grönroos, C., An applied service marketing theory. European Journal of Marketing, 16(7), 1982, 30–41; Grönroos, C., Strategic Management and Marketing in the Service Sector. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute, 1983. See also Grönroos, C., On defining marketing: finding a new roadmap for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(4), 2006, 395–417.

3. See Hedberg, B., Dahlgren, G., Hansson, J. & Olve, N.-G., Virtual Organizations and Beyond: Discovering Imaginary Systems. London: John Wiley & Sons, 1997. Also, see Piercy, N.F. & Cravens, D., The network paradigm and the marketing organization. European Journal of Marketing, 29(3), 1995, 7–34.

4. See, for example, Achrol, R.S. & Kotler, P., Marketing in the network economy. Journal of Marketing, 63, Special Issue, 1999, 146–163. The authors distinguish between internal, vertical, intermarket and opportunity networks.

5. The first researcher to point this out in the context of service marketing was Evert Gummesson. See Gummesson, 1979, op. cit.

6. Gummesson, E., Marketing revisited: the crucial role of the part-time marketer. European Journal of Marketing, 25(2), 1991, 60–67.

7. Gummesson, 1991, op. cit. p. 72.

8. See, for example, Rust, R.T., Moorman, C. & Bhalla, G., Rethinking marketing. Harvard Business Review, 88, Jan–Feb, 2010, 94–101, where the authors advocate for ‘customer departments’ replacing ‘marketing departments’. See also Leeflang, P., Paving the way for ‘distinguished marketing’. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28(2), 2011, 76–88, where the author discusses a new role of marketing in the organization.

9. Grönroos, 1983, op. cit.

10. The notion of marketing departments as organizational traps for service providers was first introduced in Grönroos, 1983, op. cit., based on a large study in the service sector in Scandinavia.

11. Grönroos, 1983, op. cit. See also Simon, H., Hidden Champions. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1996; Piercy, N.F., Market-Led Strategic Change. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992.

12. Jan Carlzon, former managing director and president of SAS (Scandinavian Airlines System), who in the 1980s successfully turned around this airline to a highly service-oriented and profitable firm, used the notion of inverting the organizational pyramid. See Carlzon, J., Moments of Truth. Cambridge, Ma: Ballinger, 1987. Translated into English, the title of the Swedish original was ‘Tear down the Pyramids’. Recently, the idea of turning the organizational pyramid upside down has been reinvented. See Jacobson, M.D., Turning the Pyramid Upside Down. a New Leadership Model. New York: Diversion Books, 2013.

13. The concept of internal customer was introduced to the service and relationship marketing context by Gummesson. See Gummesson, E., Total Relationship Marketing. Rethinking Marketing Management. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2008.

14. The line of visibility concept was introduced in the service marketing literature by Lynn Shostack as part of her service blueprinting model. See Shostack, G.L., Designing services that deliver. Harvard Business Review, Jan–Feb, 1984.

15. There is a discussion of customer centricity and customer-centric organizations in the literature. See, for example, Harris, J.E., Customer centricity: what it is, what it isn’t, and why it matters. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(5), 2012, 392–393, and Shah, D., Rust, R.T., Parasuraman, A., Staelin, R. & Day, G.S., The path to customer centricity. Journal of Service Research, 9(2), 2006, 113–124. See also Galbraih, J.R., Designing the Customer-centric Organization: A Guide to Strategy, Structure, and Process. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

16. See Peppers, D. & Rogers, M., Enterprise One-to-One. London: Currency/Doubleday, 1997, who discuss the issues of identified individual one-person segments by creating interactive interfaces with customers and by mass customizing solutions to them.

17. See Lehtinen, J., Quality-oriented Services Marketing. The University of Tampere, Finland, 1986, which introduced this three-stage approach.

18. Grönroos, C., Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990.