Chapter 4

Starting from Zero

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Determining the first steps to embark on your smart city journey

Determining the first steps to embark on your smart city journey

![]() Exploring the essential role of city leadership

Exploring the essential role of city leadership

![]() Identifying and building your smart city teams

Identifying and building your smart city teams

It may appear that the smart city movement is well under way and that thousands of cities around the world are in the process of getting “smarter.” The reality is that cities are at the beginning of the transition that many of them will eventually undergo to utilize new technologies, data, and reengineered processes to improve the quality of life for their constituents. Most communities that make the decision to embark on the smart city journey are starting from zero. At that point, the pressing question for any city leader is, “How do we start?”

This chapter suggests that the right starting point (assuming that the motivation is there and there’s agreement on pursuing a smart city strategy by city leaders and members of the community) is to establish a vision for the effort ahead. The vision should be created by participants who are empowered to move forward and make the magic of smarter communities happen. I propose here the types of leaders and teams who should be put in place to increase the likelihood of success. All these steps set the stage for creating a successful smart city strategy.

Establishing a Vision

So you, your colleagues, and members of the community have decided that increasing the quality of life and solving complex challenges by using technology — coupled with data, new processes, and a progressive disposition toward innovation — is the right path for your city. You want to take a smarter city approach going forward.

Well done!

No, seriously. The decision to act on something, to take a particular path relative to the action itself, can be the hardest part. It’s always possible to become entrenched in debate, to fail to find common ground, or to reach an impasse. But once some form of agreement is reached, even if just marginally directional, you should celebrate.

One of the most important big decisions that has to be made at the beginning of a smart city effort is the establishment of a vision or vision statement. This vision is a top-level guide for almost all decisions to come.

I help you explore this topic in the next couple of sections.

Identifying the role of city leadership

Leadership and management are terms that are often used interchangeably. That’s a mistake. Although there are some underlying similarities, they are different. Each requires and utilizes a specific approach and mindset.

- Management is doing things right.

- Leadership is doing the right things.

It’s an essential distinction attributed to the management guru Peter Drucker. It’s one of the reasons that management can be learned, but leadership has qualities that some fortunate people possess from birth and can’t be easily acquired by training — such as charisma.

Sure, many aspects of leadership can be learned, but it’s obvious that remarkable leaders don’t necessarily acquire their skills from books. It’s a little frustrating for those trying to be great leaders when they realize that they can learn and practice most skills but will always have a deficit relative to those unique leadership qualities that require something special.

That said, the body of knowledge today on leadership is enough to help most leaders acquire the essential skills. Any given leadership team will have some with learned skills and some with natural abilities. That’s the case on city leadership teams, too.

Smart city work suffers without great leadership. After all, research from across all industries suggests that projects generally succeed or fail depending on the availability of consistent high quality leadership support.

Who are these city leadership teams, and what might their responsibilities be relative to smart city work? To answer these questions, I’ve divided city leadership into these four basic parts:

- Elected leaders: Assuming some form of democratic process, these leaders, which can include the popular role of mayor, are chosen by the city’s constituents via voting and serve for a predetermined period. This is by far the most common process. In some jurisdictions around the world, city leaders are appointed by other bodies. In either case, these leaders typically have the primary function of setting policy, approving budgets, and passing legislation. They may originate an issue to debate, or an issue may be brought to them by any number of stakeholders, from community members to city staff. For example, if city staff proposes the smart city effort, elected officials are responsible for suggesting modifications, requesting more information, and approving or declining the request. Elected leaders absolutely must sign off on the smart city effort — particularly the vision, goals, and, ultimately, budget. A healthy public debate by elected leaders on the merits of the smart city work is valuable, as is eliciting public comment.

- Appointed leaders: Running a city on a day-to-day basis requires a set of hired leaders. The city inevitably has some form of overall leader — the public agency equivalent of a chief executive officer (CEO), such as a city manager or city administrator. This leader has assistants, deputies, and an executive team that manage the various areas of the city. These areas may include transportation, public works, planning, energy, libraries, healthcare, technology, and many more. Big cities have a large number of managed areas. The city leader and the team have the primary responsibility to implement and maintain policies. They make daily decisions and ensure that the city is operational and responsive to community needs. These leaders also propose initiatives to elected officials. A smart city effort may originate this way. It’s also possible, for example, that a strong mayor will ask for staff to develop a smart city plan and propose it to the elected leaders for approval. Appointed leaders are accountable to elected leaders and, by extension, to the community.

- Leadership support and oversight: In this category, a small leadership team is tasked with originating a draft policy, recommendations, or other decision-making instruments on behalf of either the elected or appointed leaders. These teams, which have a guiding function, aren’t decision-making bodies. However, they are essential contributors toward city leadership. These teams can be permanent or temporary, depending on their function. For example, the elected leaders may opt to create a committee to oversee and make recommendations and provide reporting oversight on the efforts of a smart city initiative. The team may exist only as long as the smart city initiative continues. Alternatively, a city may have a permanent transportation committee whose role is to make recommendations on matters related to transportation. Because this area is often included in smart city work, it may be the body that’s approached for leadership input. These teams are typically made up of suitably qualified members of the community.

-

Regulatory leadership: This category is a broad one, in order to capture a range of other leaders who may have input in a city’s decision-making process. The most obvious groups include those who make regulations at a regional or national level. For example, a national set of rules on how drones can be deployed in cities may be made by a leadership group outside of a particular city, but that city would be required to adhere to the rules. This can make sense so that all cities in a region or country follow the same set of rules.

People often debate how much power a city should have over its operations relative to the power of those at the regional or national level. Cities clearly want as much autonomy as possible, but the benefits of standards at a national and even global level have important merit as well. An example of an area where a city can benefit from national decision-making in the smart city domain is telecommunications. A national commitment to supporting infrastructure standards, and also financial assistance, benefits everyone. An example of global leadership is managing the climate crisis. Even though cities and nations have to sign on, the leadership and guidance may come from a global entity.

People often debate how much power a city should have over its operations relative to the power of those at the regional or national level. Cities clearly want as much autonomy as possible, but the benefits of standards at a national and even global level have important merit as well. An example of an area where a city can benefit from national decision-making in the smart city domain is telecommunications. A national commitment to supporting infrastructure standards, and also financial assistance, benefits everyone. An example of global leadership is managing the climate crisis. Even though cities and nations have to sign on, the leadership and guidance may come from a global entity.

Creating a vision

Your city has decided to embark on a smart city journey. Great! Now it’s time to create a vision or vision statement. What is a vision, and how is it created?

A vision is a statement of what you desire the future to be. It’s not tactics or operations. It’s not projects or deliverables. It’s simply a statement that guides the development of a strategic plan — called the envisioning process — and the decisions made throughout the journey.

I discuss how to create a smart city strategy in Chapter 5, but to help you better understand the role of a vision in the strategic plan, let’s take a quick look at how I define strategic planning:

Strategic planning is the systematic process of envisioning a desired future and translating this vision into broadly defined goals or objectives and a sequence of steps to achieve them.

Put another way, the strategic plan is the translation of a strategic vision into outcomes.

A vision isn’t the same as a mission. An organization's mission is what it does and how it does it, and it includes its shorter-term objectives. Your vision is none of those things. It’s long-term and future-oriented, and it describes a big-picture future state. It has clarity and passion.

Here are ten tips for creating an outstanding vision statement:

- Think long-term.

- Brainstorm what a big future outcome would look like. Choose the one that gains consensus.

- Use simple words. Don’t use jargon.

- Make the statement inspiring.

- Ensure that the entire vision statement is easy to understand.

- Eliminate ambiguity. Anyone should be able to have a common understanding of what's actually involved.

- Consider making the statement time-bound. For example, use language such as “By 2030 …”

- Allude to organizational values and culture.

- Make the statement sufficiently challenging that it conveys a sense of ambition and boldness.

- Involve many stakeholders.

Here are some brief vision statement examples:

- Ben & Jerry's: “Making the best ice cream in the nicest possible way.”

- Habitat for Humanity: “A world where everyone has a decent place to live.”

- Caterpillar: “Our vision is a world in which all people's basic needs — such as shelter, clean water, sanitation, food and reliable power — are fulfilled in an environmentally sustainable way, and a company that improves the quality of the environment and the communities where we live and work.”

- Hilton Hotels & Resorts: “To fill the earth with the light and warmth of hospitality.”

- Samsung: “Inspire the world, create the future.”

- Smart Dubai: “To be the happiest city on earth.”

- Safe city: Leverage technology to make San José the safest big city in America.

- Inclusive city: Ensure that all residents, businesses, and organizations can participate in and benefit from the prosperity and culture of innovation in Silicon Valley.

- User-friendly city: Create digital platforms to improve transparency, empower residents to actively engage in the governance of their city, and make the city more responsive to the complex and growing demands of the community.

- Sustainable city: Use technology to address energy, water, and climate challenges to enable sustainable growth.

- Demonstration city: Reimagine the city as a laboratory and platform for the most impactful, transformative technologies that will shape how people live and work in the future.

More details of San Jose’s smart city work can be found here:

Building a Smart City Team

To succeed in moving forward with a commitment to design and to build a smarter city requires the assembly of one or more smart city teams. In fact, it’s probably the first step for the executive tasked with sponsoring the effort, a person appropriately called the executive sponsor. This person is ultimately accountable for the outcomes of the strategy. The role is usually appointed to an existing senior leader in the organization. Above all, this person must have the authority to approve or decline significant strategic recommendations. It wouldn’t be unusual for the city manager or city administrator to be the executive sponsor.

Building one or more teams requires a set of answers to some important questions, which might include these:

- What type of governance should be considered? (For more on governance types, see Chapter 6.)

- What skills will be required?

- Is this a full-time or part-time commitment for team members?

- Will existing staff be used, or will people be hired?

- Will the team be made up of only city staff, or will other stakeholders be engaged?

Identifying team members

Let me tell you right off the bat: The teams I refer to in this section are those with responsibility for the design and build of smart city initiatives. In this section, I don’t consider the talent you need in order to maintain the work after it’s deployed. Operations, support, and maintenance of completed solutions should be determined in the project scoping phase of each smart city solution.

-

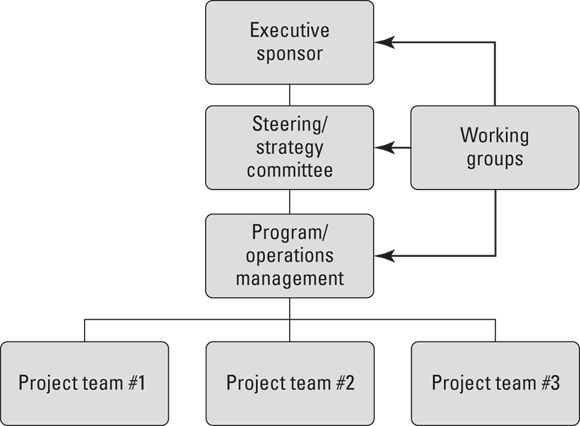

Strategy/steering committee: This team has overall responsibility for the success of the initiative. It’s at the executive level, and it includes only those with significant decision-making authority, including, most importantly, all funding decisions. A director-level job classification is typically appropriate. These teams are sometimes referred to as a steering committee because, well, they steer the work.

The types of candidates in this group might include

- City managers or their appointees

- Elected leadership representatives

- Qualified members of the community

- Executives from a management consulting organization

-

City department leaders from these areas:

Technology

Public works

Transportation

Information security

Communications

Telecommunications

Finance

Legal

Planning

This may be a good opportunity to include senior executives from the community who have appropriate experience. The strategy team can determine the smart city vision or wait to include the operations team as well. This choice is one that the team can make. After the scope has been determined, this group will likely add members.

Meeting frequency is determined on a case-by-case basis, but I recommend no less than once every three months. As a bonus, this steering committee forces disparate departments to work together. Though cross-department work does happen between a handful of teams, it’s seldom frequent, and it doesn’t happen that often between a large number of departments.

Meeting frequency is determined on a case-by-case basis, but I recommend no less than once every three months. As a bonus, this steering committee forces disparate departments to work together. Though cross-department work does happen between a handful of teams, it’s seldom frequent, and it doesn’t happen that often between a large number of departments. -

Operations/program management: This team concerns itself with the day-to-day running of the smart city initiative. They are hands-on, they have an appropriate level of decision-making authority, and they are experts in their respective areas. Members develop work plans, assign responsibilities, monitor and review progress, provide regular and timely guidance, and solve operational challenges.

A smart city initiative made up of many projects may be called a program. In this case, the operations team can be said to be responsible for program management. The candidates for this group are appointed by, and then accountable to, the strategy team. Eliciting nominations can be a great way to get more participation from across the organization. Members of this team are typically made up of only city staff. This team should include members of city staff who are passionate about the topic of smart cities — you’ll find these people in every organization. Tap into their passion.

Determine the meeting frequency for the operations/program management team on a case-by-case basis. I suggest no less than once every month.

Determine the meeting frequency for the operations/program management team on a case-by-case basis. I suggest no less than once every month. -

Project management office (PMO): Each solution that’s designed and built in the smart city initiative is likely to have a project team. This is the least mysterious part of team governance because project teams exist as a product of most organizational efforts. After all, that’s how complex work with a defined beginning, middle, and end typically gets developed and deployed. Project teams can be made up of city staff only or city staff and vendors. Sometimes, a vendor does all day-to-day work under the guidance of a single city project manager. Project teams are accountable to the operations team.

Depending on the scale of activities involved, you can consider establishing a project management office (PMO) specifically for the smart city work.

Here are the typical core functions of a PMO:

- Prioritizing projects based on strategy and resources

- Managing resource capacity and skills

- Enforcing project standards, methods, and processes

- Producing project and program reports

- Monitoring progress, resources, budgets, and schedules

- Providing administrative and operational support

- Working group: This team, which is typically temporary, is tasked with a specific set of goals. Experts in a particular area, they have a defined period in which to research, develop insights, and report back on a given assignment. Given the scale and complexity of smart city efforts, working groups (plural because you typically see several in the life of a program) are highly valuable teams that can bring important knowledge and recommendations to the steering committee and operations team. Here are some types of work a working group typically performs:

- Developing a recommendations document

- Creating a standard, such as a naming convention, or technology implementation

- Resolving complex problems that need independence from other teams

- Suggesting improvements

- Identifying possible issues now and in the future

- Conducting research

To help you conceptualize the reporting relationships of the tiers, I’ve created a visual of a high-level organizational structure in Figure 4-1.

FIGURE 4-1: Basic smart city team organizational structure.

Creating a RACI chart

Without a doubt, developing and implementing a smart city strategy is large, complex, and messy work. There are going to be a lot of teams, participants, and responsibilities. Despite your best efforts, some team members are going to get confused about what their roles are in each step of the work. What you’ll want is a tool that everyone can use to quickly achieve clarity on roles and responsibilities. What you need to create is a RACI chart.

A RACI chart is a simple matrix used to assign roles and responsibilities for each task, milestone, or decision on a project. RACI stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed. By documenting which roles and responsibilities are involved in each task, you can eliminate confusion. RACI charts answer the frequent project question: Who’s doing what?

With a RACI chart, expectations can be set for everyone on the team. It should also help to avoid multiple people working on the same task or in conflict with each other because responsibilities weren’t clearly defined or understood at the beginning of the work.

The four role responsibilities are described here:

- Responsible (R): Performs the work to complete the task

- Accountable (A): Determines if the work has been completed satisfactorily

- Consulted (C): Provides input through expertise and experience

- Informed (I): Kept in the loop on progress with the task

A RACI chart doesn’t require any fancy software, although plenty exists. I use a basic spreadsheet. See Figure 4-2 for a simple example.

FIGURE 4-2: A simple RACI chart.

Getting the team on the same page

I would bet that many people believe that a smart city strategy is another technology initiative. For this reason, city leaders and staff often assume that the smart city strategy will be managed and executed by the technology team. As I discuss in Chapter 2, in the sections that spell out what a smart city is and what it is not, it’s not simply a technology-centric endeavor. Sure, technology plays a big role, but it should be considered an enabler, not the definition of the outcome.

When the executive sponsor kicks off that first meeting of the steering committee, it’s essential to get the team on the same page. A common understanding of the nature of the initiative is important to establish from the outset.

Here are some suggested topics to discuss (possibly over more than one meeting):

- What is the motivation for the smart city initiative?

- Is there a notion of the scope of the endeavor at the highest level?

- What might success look like along the way?

- How will progress and outcomes be measured?

- How will the effort be communicated, and to whom?

- Who might be involved?

- How much might the initiative cost? (This item is particularly complex. For example, it might be the job of the steering committee to provide estimates only after the scoping effort is completed. However, an estimated range is valuable in order to give the team a sense of the magnitude of the work ahead.)

Of course, many more topics can be discussed, which should be determined on a case-by-case basis dependent on your city.

Here are some additional techniques for getting new teams on the same page and having them remain there:

- Using icebreaker exercises that are relevant to the topic.

- Involving team members in as many aspects of planning as possible.

- The creation of, and agreement on, initiative values (which should be displayed in meetings and included in meeting minutes and in any online platforms).

- Sponsoring one or more education events that may help to level the knowledge playing field when it comes to the smart city domain. You’ll never go wrong by offering training in business analysis, project management, communication skills, and facilitation techniques.

- Communicating often and mixing communication methods between electronic and in-person modalities.

- Prioritizing transparency.

- Taking advantage of collaboration tools.

- Centralizing information.

The smart city movement remains largely in its infancy. The vast majority of cities in the world have yet to embark on this journey (assuming that it’s the right direction for many of them). They are starting from zero. As with any initiative, it’s easy to jump directly into the tactics after receiving direction to pursue smart city goals. But I think that would be a mistake. The first step on any smart city journey needs to be the establishment of an agreed-on vision. That vision guides strategy, and strategy directs the work.

The smart city movement remains largely in its infancy. The vast majority of cities in the world have yet to embark on this journey (assuming that it’s the right direction for many of them). They are starting from zero. As with any initiative, it’s easy to jump directly into the tactics after receiving direction to pursue smart city goals. But I think that would be a mistake. The first step on any smart city journey needs to be the establishment of an agreed-on vision. That vision guides strategy, and strategy directs the work.