Chapter 6

Enabling a Smart City Strategy

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Developing policies and regulations

Developing policies and regulations

![]() Identifying funding sources

Identifying funding sources

![]() Choosing options for procurement

Choosing options for procurement

![]() Implementing governance

Implementing governance

![]() Reporting on progress

Reporting on progress

Establishing a smart city involves more than just identifying technology and deploying it to your community, and the task is certainly more diverse in the range of implementation options available. Smart city work is also about having smart regulations in place, improving training for city staff, and creating policies for improved environmental management. Whatever it is that you do to make your community smarter — whether it’s as a city official, community member, vendor, or some other stakeholder — it has to begin and end with people, and it has to focus on improving the quality of life for everyone. To make this happen, you first need a vision and a strategy, and then you need the tools to enable a successful program to be implemented.

When it comes to tools, I’m not simply referring to the software and hardware required in your projects — although those elements are vital. Instead, you also need some of the bureaucracy that comes with proper regulations and policies, a variety of options for procurement, and the adoption of mature governance practices. These aspects may not be the most glamorous ones in smart city work, but they’re essential.

In this chapter, I help you explore each of these areas in detail so that you can gain a greater appreciation of their value. With the stakes and the risks high in building sustainable and smarter cities, you need all the right tools and best practices available to you, to increase your chance of success.

Putting the Building Blocks in Place

Cities are complex beasts. Even a medium-size city might provide, and support, hundreds of different types of services. For the community member, the expectation is that the services just work. Sure, they may not always be seamless or even the most efficient, but the baseline expectation is that they have to deliver. Behind the scenes, people, processes, and systems must work together in order to acquire, process, and execute on requests. Every single day, this may happen hundreds or even thousands of times.

It's not just the high number of necessary services, and the variety of supporting technologies and processes, that add to the complexity of urban life. What elevates the delivery of city government a few notches in difficulty is that everything must take place in the context of rigorous and comprehensive rules. These rules have evolved over a long period, and they represent, for example, guidance on making decisions, protections for people, and a way to enforce law. Of course, a smart city must adhere to these rules, but the requirements of a smart city may necessitate updates to certain rules and even the creation of new rules. Without a doubt, building a smart city requires attention to rules.

The building blocks of a successful smart city strategy also include many other, nontechnical requirements. The smart city team needs to consider how the work will be funded. The money may come from the city’s general fund, but in a tight financial environment, might other sources of funding be available? The team also needs to look at the procurement process and determine how it can support the goals of the work. For example, are there mechanisms to move faster or to support experimental work? Finally, a smart city team will be well-served by ensuring that they have the right project management structure and processes in place. After all, a smart city strategy is about execution. Great project management is a vital ingredient of success for any effort.

Developing policy

The basic role of government is to help provide services that benefit the well-being of a community and to work toward increasing quality of life. (Though I encourage you to explore the large body of knowledge on the role and purpose of government, the definition I provide here should suffice for this book.) Governing is a daunting and complicated task. Government bodies that are made up of people with different backgrounds and perspectives typically have principles that guide decision-making. All decisions have consequences and must be deliberated carefully. To support this deliberative process, governments develop and enforce something called policies.

A government policy is a rule that guides decisions in order to benefit the community. A policy documents the reasons that things are done a certain way. Policies lead to the development of procedures and protocols that describe the How, Where, and When of how the policies will be delivered. Though policies are not laws, they can often lead to the creation of laws. By extension, the enforcement of laws is often guided by policy.

Here are some examples of government policies that guide how decisions are made in a city jurisdiction:

- Recycling requirements

- Crime reduction

- Poverty remediation

- Affordable housing

- Public transportation

- Public safety

- Urban innovation

The need to update and create policies is driven by many factors — new ideas, new needs, federal laws, and an evolving culture, for example. The introduction of innovation and technologies related to the smart city movement is a driver of policy work. For example, cities have had to respond to the emergence of ride hailing services such as Uber, Grab, and DiDi. This policy development is often reactive because many of these new services emerge and descend on cities quickly. Given the original nature of many of these urban innovations, there’s a low likelihood that existing policy will suffice. As a result, once a new service arrives, policymakers scramble to respond.

Creating and updating city government policies has become a core smart city strategy requirement. It’s not easy work, but having relevant and supportable policies is essential.

Getting started

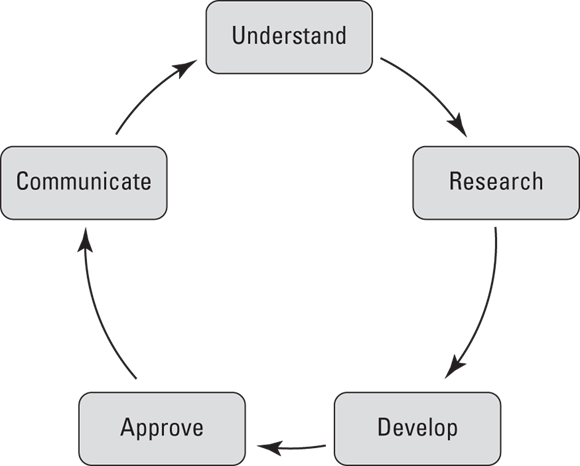

These steps succinctly spell out the process for developing government policy:

-

Understand.

First, fully determine the need for the policy. It may involve interviews and discussions with many stakeholders. Because policy-driven issues can be complex, it’s essential to secure agreement on the core of the problem. Understanding context is vital, as is identifying and agreeing on the outcome of the policy.

-

Research.

After the need has been established, those tasked with policy development conduct research, ranging from understanding existing policy to digging deeper into the challenge. You should conduct a thorough analysis and, by all means, ensure that all stakeholders are actively involved.

-

Develop.

With all the information gathered, it’s time to develop the policy itself. As with every step of policy creation, be sure to involve all relevant stakeholders. Development should be based on evidence and data. It’s often important to consider the wider context of political, economic, technological, and environmental trends.

-

Approve.

Each government entity has (or should have) an approval process that must be followed. This process is smoother when you involve all the right stakeholders in earlier steps. Approval may undergo several iterations before final acceptance. Receiving feedback and editing requests from decision-makers is normal.

-

Communicate.

After the policy is completed and approved, it’s time to determine the communications strategy. The policy should be posted in a central policy database that is open and searchable. In addition, other communication channels should be used that are relevant to the policy. For example, it doesn’t make sense to include a new policy in an email to the community when the policy will be used by only one city department.

Figure 6-1 gives you a graphical illustration of this process.

Many of the steps in the preceding list can be conducted in a workshop setting. All steps should include as many stakeholders as possible. In this instance, it may be better to have too many cooks than too few.

FIGURE 6-1: The basic steps in creating a government policy.

Examining a few examples of smart city policies

Need some concrete examples of smart city policies? Here you go:

-

Data protection and usage: The collection and use of data are central to the delivery of smart services in a city. For example, one could use Internet of Things (IoT) sensors on light posts to collect air quality samples or measure noise levels or count vehicles at an intersection. (See Chapter 8 for more on IoT.) Capturing this data and delivering meaningful results to decision-makers and other interested stakeholders can have real value.

Collecting data can also mean inadvertently capturing sensitive data. For example, a camera at an intersection may be used for dynamically changing the light signals, but it may also record the license plates and occupants of a vehicle. To protect any data that’s collected, determine how it may only be used. To protect privacy, policies should be developed to help manage the design and deployment of data collection technologies.

Collecting data can also mean inadvertently capturing sensitive data. For example, a camera at an intersection may be used for dynamically changing the light signals, but it may also record the license plates and occupants of a vehicle. To protect any data that’s collected, determine how it may only be used. To protect privacy, policies should be developed to help manage the design and deployment of data collection technologies. - Open data: Making government datasets freely available and in machine-readable form — a concept known as open data — is a core smart city capability. (I discuss open data in more detail in Chapter 9.) For example, open data can increase transparency, reduce the cost of data acquisition for requestors, and be useful for people who want to build solutions based on city data. Governing the use of an open data portal is typically enhanced by the creation of relevant policies. For example, how often is new data published and existing data updated? What’s the policy when a request is made to delete data? You need to consider these aspects — as well as many others — if you want to impose consistency on your decision-making process.

- Standardization: The design and building of smart city solutions involves many different technologies from a wide variety of vendors. A digital infrastructure is optimized when data and system functions are integrated. Some cities may acquire a central smart city platform that requires the integration of other systems. It’s advisable for the technical architecture underlying smart city solutions to be scalable and supportable for a long time to come. For this reason, you need to establish technical standards early on in the process. Standards may include file formats, naming conventions, back-end database systems, and application programming interfaces (APIs). Policies are a great way to support the adherence to, and adoption of, standards.

Establishing regulations

Both regulations and policies are rules created by city governments; however, they differ in important ways. Though a policy is created to help make decisions and to achieve outcomes, a regulation is a rule that is made to ensure compliance. It’s comparable with a law and imposes some form of a restriction to ensure that people follow a specific set of rules. Unlike laws, which typically require elected officials to pass, regulations are can be created by professional staff within a city. In addition, regulations often describe in greater detail how laws are implemented in a local government. Finally, regulations are administrative and are used to enable successful operations within an organization.

Here are some examples of city regulations:

- Zoning: This involves the process of designating land in a city into zones in which certain land uses are permitted or prohibited. It’s the most common regulator for cities to carry out their urban plans. Examples of items regulated in zoning include buildings, parking, signs, walls, factories, and commercial entities.

- Business licensing: Many cities do not permit a business to operate until it has been issued a certificate of occupancy. Attaining the certificate may require the business meeting regulations, which may include vetting that the business type is allowed, that safety concerns are addressed, and that accessibility accommodations are made.

- Building improvements, construction, and remodeling: Cities require strict adherence to regulations governing areas such as electrical, plumbing, and mechanical work. In addition, those hired to do the work may be required to have a city business license and worker insurance.

- Drones usage: The use of drones for both recreational and professional use is growing quickly. In addition to countries that have federal laws and regulations on drone use, some cities have adopted their own, more restrictive rules. Regulations may include how drones are used, where they are used, whether a permit is required, and limits on video recording to protect privacy.

Developing regulations

Fortunately, the process of creating a regulation largely follows the same pattern as a policy. (Refer to Figure 6-1.) Though regulations can be created as a standalone set of rules, often it’s the result of the passing of a new law. As a result, in this instance, developing a regulation is based on the content of the law. As with a policy, comprehensive and regular engagement with stakeholders is essential to capture feedback and evolve the regulation. How regulation is created depends on each city’s agreed-on processes, so it’s important to understand the local approach when considering this topic. In addition, many larger, noncity government agencies have specific mechanisms in place when it comes to formulating regulations.

Ensuring regulations support smart cities

Clearly, city rules are an important part of the context of smart city efforts. Regulations impact strategy and implementation decisions, and the opposite is also true: Smart city work can result in the modification or creation of regulations.

The traditional model of public regulation is being challenged by the nature of smart cities as they drive a new relationship between technology, government, and society. Specifically, the rapid emergence of new urban innovation presents the question of whether existing legal mechanisms can strike the right balance for the current and future needs of smart cities. Simply put, recognizing and accommodating the benefits of new solutions in response to city needs and also encouraging the right level of innovation should not be limited by traditional regulatory considerations. City leaders may need to be open to modifying and creating regulations to support the realities of 21st century smart and sustainable cities.

To understand the seriousness of the challenges and considerations outlined here, let me briefly discuss regulation through the lens of economic and social issues.

In the case of economics, regulations should avoid regulatory asymmetry — different rules for different players in the same market, in other words. New innovation creates new business models. For example, a ride hailing service such as Uber provides the same service as taxis do, but in a completely new way. Regulation may support the old model of taxis and punish the new model of ride hailing. (With this example, I don’t mean to trivialize the important debate about the potential destructive nature on incumbents from new business models such as ride-hailing.)

Older rules should be evaluated to ensure that all permissible participants in a marketplace have equal and fair competitive access. In a related matter, regulation must not create barriers to entry for new players by continuing to enforce old and outdated standards and rules. In fact, regulation should encourage more entrants, in order to increase urban innovation.

In the case of social issues, regulation must protect society from the potential harm of any new technology. Though innovation brings solutions, it can also introduce new problems. For example, increased threats to personal privacy and digital exclusion are real possibilities in smart cities.

These examples of the economic and social aspects of government regulations in the age of smart cities point to a need for city leaders to evolve and embrace the changes necessary to respond to new realities on the ground.

Smart cities need smart regulation.

Evaluating funding models

There’s one consistent truth when it comes to working in city government: There are always more projects to be completed than there are available resources, such as talent and money. Demands for government services continue to increase as communities expect more and operating a city becomes more complex. Simply meeting existing operating costs can consume most of a municipality’s annual budget. In the worst case, some even run an annual deficit. A few fortunate cities have revenues that enable them to comfortably meet all operational needs and also build for the future, but for most, the reality is more sobering. These cities can meet most operational needs, but choosing which projects to fund and tackle each year is a matter of rigorous prioritization. Many projects will be deferred or may never be completed. They’ll just be declined. All this takes place during the annual budgeting process.

Now that cities are beginning to focus on developing smart city strategies, the central question of how the attendant projects will be paid for has quickly risen to the top of the agenda. In fact, in several surveys, a lack of available funding is cited as the main reason that smart city efforts aren’t being pursued. Smart city projects often require significant investment in existing or new infrastructure. Beyond deployment, there’s also the need to ensure that funding is available to support the long-term operation and maintenance of the solutions.

For many cities, the smart city strategy and its related annual project requests are processed via the normal annual budgeting cycle. This means acquiring funds from the city’s revenue that is derived from taxes, service fees, and other sources of income. The team responsible for the smart city effort is required to participate in the budgeting process, just like every other city department. They need to write up the business case and make a compelling pitch for funding approval. Gaining agreement is more likely when those making the budgeting decisions have already bought into the smart city strategy. Extensive planning, preparation, and stakeholder engagement prior to the budgeting process — particularly of relevant leadership — is of paramount importance here.

Though the annual budgeting process is the primary source of funds for many smart city projects, many cities may find that this avenue either isn’t an option or will fall desperately short of what is required to support an expensive, multiyear effort. As a consequence, alternative funding and financing options need to be explored.

Such funding can be grouped into these four categories:

-

Private: Here, funds for the project come from a private enterprise source. A privately owned city service organization, such as a power utility, funds its own upgrades and innovations, for example. Some of the reasons they’re motivated to do this is to meet customer expectations, improve safety, and reduce operational costs.

Another example is the large and continual investment that telecommunication companies make in communities to ensure support for wired and wireless communications. Many telecommunication companies now also provide smart city services such as digital signage, Wi-Fi, IoT services, and sensor networks.

Private enterprises can also engage in contract operations for cities. This means that the upfront design and build costs are absorbed by the private company, and the city then pays a monthly or annual fee for them to provide the service. For the city, such an arrangement means that it avoids capital costs and is responsible only for an operating fee.

Other private sources may include grants that are nonrepayable funds given by a charity, foundation, or corporation. Though grants may be difficult to win because of their competitive nature, they can often be worth the effort.

-

Public: In this model, funds are sourced only from government entities. In addition to the local government funding projects in the annual budgeting process, money can come from regional and national governments. These funds may be used for major infrastructure upgrades, such as those related to transportation and water systems. Regional and national governments often make available funds in the form of subsidies to poorer areas to improve economic and social conditions. National governments are also investing in smart city efforts to encourage community innovation, conduct city-scale urban improvement experiments, and kick-start compelling city projects.

Another way that public funds can be made available is through projects that reduce operational costs. Smart city projects often create efficiencies that result in lower costs. The money saved can then be used for other smart city projects.

Another way that public funds can be made available is through projects that reduce operational costs. Smart city projects often create efficiencies that result in lower costs. The money saved can then be used for other smart city projects.Though not popular for obvious reasons, cities can increase a tax or impose a temporary tax or tariff to raise specific funds.

Where relevant, a city can also impose a service fee on a new smart city service. The fee repays the cost of the project and supports the ongoing operations and maintenance of the solution. Fees can also be applied to existing services in order to raise funds for a project. For example, one could increase street-side parking fees or costs for city permits.

-

Public-private partnership (PPP): Here, funds are derived from both private and public organizations, which allows private enterprise and local government to collaborate so that they can provide input as well as funds for a project. Such partnerships are often favored approaches because risk is shared among participants. An example of a PPP is a shared revenue stream. If the smart city project generates revenue, such as from a new parking system, the government and the private company agree to split any revenue from the service.

PPPs are gaining popularity in experimental urban innovation work as well. In this model, the city may provide some funds and resources in order to incentivize an innovative technology company to experiment in the community. I discuss this approach in detail in Chapter 7.

Smart city projects funded by advertisements are often PPPs but can also be privately funded exclusively, depending on the arrangement with city hall. For example, a private company may get permission to build modern bus stop shelters with digital signage. They will then sell add space on the digital signage which can produce significant funds depending on location. A city might negotiate a revenue-share in this example as well.

Community members working alongside their local government can crowd-source funds for special projects. Crowd-sourcing is a method of raising finance by asking a large number of people for a small amount of money apiece. Though possible as a private approach, collaborating with your city is a better way to increase the chance of success.

Given the effort it takes to win large grants, a PPP approach is often preferred because it means sharing the burden and having each partner exercise their strengths.

-

Financing: In this model, funds provided by a financial institution are borrowed on the understanding that they must be repaid under an agreed-on plan. An example is acquiring a long-term loan from a bank.

Another popular form of financing is the issuance of a bond. A government bond is issued to investors that promises to pay periodic interest payments and then to repay the full amount of the investment on the maturity date of the bond.

Financial organizations can offer cities a variety of loan services. However, raising money for smart city projects this way can result in push-back from financial institutions. These are some reasons they may cite:

- Bad municipal credit ratings

- The risks of new technology

- A lack of a clear business case

Handling procurement issues

You’ve addressed the source of funding for some or all of your smart city strategy. Yippee! Now it’s time to spend it. Beyond identifying funds for delivering smart city projects, another priority area that can be challenging is the procurement process. Intuitively, particularly with a private sector mindset, it may seem like identifying and purchasing solutions would be one of the easier processes. However, the important qualities of being transparent and enabling the marketplace to have a fair shot at competing requires a notable amount of bureaucracy and regulation. There is a high degree of responsibility and accountability when spending large sums of public money, and it’s important to openly demonstrate prudent and diligent processes and behavior. In a 2019 survey of city leaders, 44 percent of them maintained that procurement was a significant challenge in building a smarter city.

In general, the traditional procurement process requires that an agency builds out a detailed request for proposals (RFP) document and submits it to the marketplace. An RFP typically includes exhaustive details on the solution required, the requirements expected from the vendor, and the context of the need. Vendors are then expected to submit their responses within a specific timeline. Respondents who meet the requirements of the RFP are invited to demonstrate their capabilities. A panel of evaluators, largely made up of city staff and perhaps other stakeholders from the community, scores each proposal. Several rounds of evaluations may occur until a winner emerges and a contract is awarded. It’s a thorough and detailed process. In terms of fairness and careful deliberation, this RFP process is effective. It’s by far the most common approach adopted by public agencies. Rules that go back many years govern the process. There’s no doubt that many of your smart city projects are procured this way.

So, what options may be available for a more creative procurement process to support the innovative nature of smart city efforts?

Public-private partnerships (PPPs)

The days of choosing a go-it-alone strategy for public agencies is largely over. It’s just no longer possible for governments to achieve their goals by themselves. Increasingly, efforts are delivered through partnering with such players as those in private industry, academia, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community members.

By partnering with innovative urban technology companies, particularly start-ups, cities can evaluate new solutions to solving problems well in advance of a full-scale procurement — a try-before-you-buy approach, in other words. For example, this may take the form of a vendor collaborating with an urban innovation lab (see Chapter 7) or demonstrating their capabilities in an innovation district (see Chapter 7). Because the vendor gains the benefits of piloting its solution — which may include positive marketing and real-world showcasing — the costs involved may be low, or there may even be no cost to the city. Though an RFP may be required at the end of the process regardless, this partnership approach enables considerable learning and other benefits for both the city and vendor. A completely novel solution may also qualify for a sole source — a procurement approach that supports the acquisition of a solution when there’s only one provider.

Another partnership approach was pioneered by the city of San Francisco in 2014. The city created a Startup-in-Residence (STiR) program. Start-ups are solicited to compete for a limited number of city slots to try to help solve identified challenges. Over 16 weeks, city staff and the matched start-ups work together to co-create solutions for the community. Called challenge-based procurement, this type of RFP specifies only the desired outcome of the solicitation rather than all the details. Start-ups typically offer a substantial discount to the hosting city so that if a sole source is not an option, the cost can fall below the open market solicitation requirement. For more on the STiR program, check out www.cityinnovate.com.

Innovative procurement methods

Here are seven alternative innovative procurement approaches:

- Piggybacking on another agency’s procurement: In some jurisdictions, it’s permissible to use the existing vendor contract work of another agency to negate the need for an RFP.

- Create procurement processes specifically for innovation: An agency may create a separate set of rules specifically for the purpose of supporting the rapid procurement of innovative technology while still adhering to the principles of transparency and accountability.

- Performance-based contracting: Rather than base procurement on upfront pricing, contracts use vendor-and-solution performance to determine cost based on the quality of execution.

- Incentivize private innovation: Create and communicate opportunities for the private sector to deliver solutions directly to the community. In addition, make open data available for private enterprises to use to create solutions. (For more on open data approaches, see Chapter 9.)

- Create an independent organization to deliver the smart city strategy: Here, a city creates a separate and independent entity that executes the smart city work. Because they aren’t subject to government procurement rules, they have more freedom when it comes to identifying and buying solutions. The city pays the entity an annual management fee. A variation of this approach involves engaging a third-party program management company to run the smart city strategy.

- Contract to multiple vendors: Create an RFP that identifies vendor capabilities rather than specific deliverables. Contract with multiple vendors in each capability area. Then utilize the vendor that best meets the need for a particular round of work at a specific time.

- Open source software: Though not technically a procurement strategy, an agency can determine whether open source software may meet an organizational need. The upside is that a great deal of high-quality open source software is available, and it may be freely used without procurement costs and modified without restrictions. For example, WordPress (

https://wordpress.org), an open source content management system, is used by almost 35 percent of all websites in the world. The downside to open source is the hidden costs. For example, third-party support may still be required.

Managing projects and carrying out business analyses

The topics of project management and business analysis may not be the first things you think about when you consider the development of a smart city. Of course, you and I recognize that it’s essential to have strong leadership and a big vision. It’s also vital to have community support and access to funding. However, all too often we overlook giving sufficient focus to how the work is executed and the necessary talent to achieve it. I’ve worked in various organizations over the past 30 years delivering hundreds of projects, and I can firmly attest that performing quality business analysis and then delivering through high-performing project management are essential ingredients to success. This is why I’m including these areas.

Project management

In Chapter 5, I discuss the steps to create and codify a smart city strategy. I explain how to get to the point where the strategic vision, goals, and objectives are defined and agreed on. After the plan is approved, it’s time to create the projects that will deliver the desired outcomes of the strategy. Next, the projects are identified, prioritized, and then scheduled. You can use a Gantt chart to visualize and manage project schedules. (Check out this overview of Gantt charts: http://bit.ly/2vuk8Ug.) Finally, assuming that funding has been established, you assign projects to specific project managers in accordance with the schedule.

The projects then begin. Good luck.

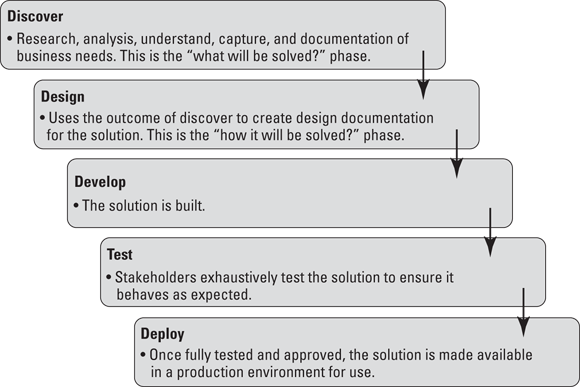

Though you have many different methods for conducting a project, ranging from the traditional waterfall approach to the current popularity of agile approaches, projects generally include the same major milestones. For technology-related projects, Figure 6-2 illustrates the universally acknowledged systems development lifecycle (SDLC).

According to the Project Management Institute (PMI), at https://www.pmi.org/, these six criteria must be met for a project to be considered successful:

- It's on time.

- It's on budget.

- It works as specified.

- People actually use the solution.

- The people who funded the work are pleased.

- All objectives have been met.

FIGURE 6-2: Systems development lifecycle (SDLC).

Meeting these criteria is a lot harder than it sounds. In fact, the data on project success is rather sobering: The research shows that, overall, 71 percent of projects fail to deliver. They fail to meet at least one of these three project criteria: It’s on time, it’s on budget, and it works as specified. The number jumps to a staggering 94 percent with really large projects.

Specific to technology-related projects, a 2017 PMI report about IT projects stated that 31 percent failed to meet their goals, 43 percent exceeded their budgets, and 49 percent were late.

Why do so many projects fail to deliver, and what should you focus on to ensure greater success for your smart city work?

Here are the top ten reasons that projects fail:

- Poorly captured organizational needs

- Lack of leadership support and involvement

- Changing project objectives

- Overpromising on timelines and underestimating costs

- Failing to confront unidentified risks

- Dependency delays

- Lacking a sufficient number of skilled people to complete required tasks

- Weak project management, including poor project communications

- Team member procrastination

- Poor user involvement

Increasing the success of your projects means paying attention and addressing the items on this list. Don’t overlook them. It may mean that you have to invest a little more time upfront, but it’s worth it. Nobody wants to endure project failures on their watch, particularly with large public initiatives where the visibility and attention are heightened. In addition to wasted public money and disappointed users, leaders and team members can face embarrassment and even termination.

Business analysis

As noted in the list of the top ten reasons that projects fail (refer to the previous section), a significant reason for project failure is poorly captured organizational needs. Eliciting these needs to deliver a successful outcome is highly skilled work. A business analyst is the one who conducts this discovery and documentation work. Knowing how to capture requirements, recording the right information, and then gaining approval from decision-makers makes a significant difference in project outcomes.

Project managers and business analysts must work closely together, particularly in the early phases of a project. (Refer to the Discover and Design phases in Figure 6-2.) Remaining engaged until the project ends is important too, in order to ensure that the business analyst can provide, to the project manager and team members, timely insights that are relevant from early analysis work.

A business analyst captures requirements from relevant stakeholders via methods such as interviews (the most popular) and observations and user surveys. This process answers the question, “What city need will be solved?” These requirements are documented and approved by decision-makers.

Requirements documentation is then used to create the design specifications. In this phase, you’re answering the question, “How will the problem be solved?” Many design methods can be used, including modeling, which is simply a way to represent some aspect of a system. The model can be text-based, graphical, or mathematics-based. A popular form of modeling, particularly for building software, is called Unified Modeling Language (UML). You can learn more about it at www.uml.org.

Governing the Strategy

A smart city strategy is only as good as the degree to which it is followed. A strategy that is written and agreed on and then never referenced again is worthless. Success in reaching goals relies on having a roadmap and a set of guiding principles that everyone can follow. But even with the best of intentions, individuals and teams can veer off course and, before long, find themselves way off track. Pulling the team and projects back into alignment with the strategy is then expensive and will incur delays. The risk of failure also increases. For this reason, to keep focused and aligned to the strategic goals — allowing, of course, for modifications along the way — requires an agreed-on management framework, a process for decision-making, and methods of enforcement. This is called governance.

In Chapter 4, I suggest how you can design an organizational structure to support the creation and implementation of your smart city strategy. Each layer of the organizational chart has a mandate and a specific set of roles and responsibilities to execute against it. Each team contributes in some way toward ensuring that the work is being governed. After all, the assumption is that all participants are focused on achieving the same goals and have agreed-on rules to get there. This requires a common understanding of why something is being done, what is being done, how it will be done, and when it will be done.

In the next few sections, I describe and recommend models for both the strategic and project governance of your smart city efforts. Finally, I share suggestions on communicating the status of your strategy.

Defining strategic governance

The term strategic governance is most often used to describe how entire organizations are managed from the top all the way to the bottom. But it can also be used to help define the management and decision framework of large organizational programs. A smart city strategy falls into this category.

As such, my definition of strategic governance runs as follows: It’s the process of envisioning a future and then managing the decisions and efforts to realize that vision. It encompasses the development, implementation, and monitoring of the strategic plan.

Strategic governance drives how each team executes the vision, mission, values, policies, and processes of their respective work. It’s a top-down approach, with leadership and guidance coming from the strategy/steering committee. Governance flows down through the various organizational layers and is executed in a way that’s appropriate to each team’s responsibilities. Figure 6-3 summarizes the role of leadership in strategic governance.

These are the core responsibilities of strategic governance:

- Defining, agreeing on, and revising your goals and objectives

- Creating and enforcing policies that provide guidance on execution

- Approving and allocating resources

- Leading and controlling activities and tasks

- Insisting on accountability for quality delivery

- Monitoring performance

- Reporting on progress

FIGURE 6-3: Basic strategic governance framework.

Managing projects with project governance

Though recognizing that creating and governing a smart city strategy is essential work, the real outcomes actually happen through your smart city projects. Even when you use the best strategy, results are bad if projects are poorly managed. Projects must meet the minimum requirements of being on time and on budget and meeting the expectations of users. There’s a vast chasm between simply managing a project and managing a project well.

Project managers and their team members require the necessary organizational conditions and environment to excel. A priority ingredient when it comes to repeatedly managing successful project outcomes is an agreed-on framework for project decision-making — project governance, in other words. It’s a direct descendant of strategic governance. Though project managers and their team members focus on the details of running a project, project governance provides them with valuable guidance, oversight, and timely decision-making.

For your purposes in this book, think of project governance as a structured system of processes and rules used to manage a project. It provides a decision-making framework to ensure alignment between the project team members, executives, and the rest of the organization. Project governance can also be used to decide the sequence and timing of projects, including the identification and assignment of project managers and team members. Figure 6-4 summarizes the core components of project governance.

FIGURE 6-4: Four central project governance functions.

These are the core components of project governance:

- Team structure: Establish the organizational structure and reporting relationships between all relevant project stakeholders. (I cover this topic in detail in Chapter 4.)

- Role definitions: Provide all stakeholders with detailed information on their role and responsibilities. Decision-making authority can be defined here as well.

- Project management plan: This formal document gets approved by all who define exactly how the project will be executed, managed, monitored, and controlled.

- Project schedule: This list of dependent and independent project milestones, activities, and deliverables is coupled with their estimated and actual start and finish dates.

- Issue review process: This agreed-on guide specifies how different types of issues encountered during the project will be handled.

- Reporting plan: This plan designates a process and a set of agreed-on methods and channels for ensuring clear and frequent communications to all stakeholders. I tell you more about this topic in the last section of this chapter, “Regularly updating and reporting.”

- Risk register: This one acts as a repository for logging and managing project risks. It also documents what actions were taken to mitigate or directly address the risk, if any.

Regularly updating and reporting

High-quality communication is a fundamental component of strategy and project success. In fact, 80 percent of a project manager's role is communicating to stakeholders. With poor communication, necessary information may not be exchanged effectively. This can have many negative impacts, including delays, omissions in scheduled tasks, bad decisions, and project errors. High-quality communication increases the likelihood of project success.

Effective status reporting is a proven method of good communication.

In this section, I discuss the use of project status reporting, but it’s just as applicable to strategy reporting as well.

Reporting is used as a vehicle to communicate to stakeholders in order to keep them informed, solicit feedback and questions, elicit action, and assist with timely decision-making. The frequency of reporting is typically decided on and documented when the project management plan is created. Not every report is sent to every stakeholder. The right report should be created for the right people. As always, know your audience.

Keep in mind that electronic project status reporting is one important form of communication, but all other channels should be kept open and used. Project managers can still speak to their colleagues as well. Yes, that means visiting their offices or picking up the phone.

Status reports also comprise a historical record of a project. The reports can be used to attain lessons learned, serve as a reference for any questions, and capture the strengths and weaknesses of various aspects of the project.

Project status reporting can include

- Overall project health

- Schedule and budget status relative to a specific stage of the project

- Project summary and milestone status

- Significant-accomplishments status

- Challenges-and-risks summary

- Open issues that must be handled

- Change requests

- Project metrics

Finally, when it comes to writing up a status report, here are some best practices you should follow:

- Consistency: Establish and maintain a uniform format, distribution frequency, and method.

- Metrics: Create and report on metrics decided during the planning phase of the project.

- Process: Develop and communicate the reporting process to team members with reporting responsibilities.

- Simplicity: Ensure that reports are clear and effective.

- Verify: Regularly confirm that distributed reports are adding value and are reaching all the right people at the right time.

- Tools: Identify and use reporting tools that lower the burden of report development and distribution.

There’s a subtle difference between public policy and the policies I describe earlier in this chapter. It’s completely unintuitive given the terms, but it’s important for me to clarify. Public policy is the process of converting political intentions into outcomes in the real world. It focuses on the decisions of politicians that result in actual policy change related to such areas as a public healthcare system, defense forces, transportation, and education. Public policies come from all governmental entities and at all levels: legislatures, courts, bureaucratic agencies, and executive offices at national, local, and state levels.

There’s a subtle difference between public policy and the policies I describe earlier in this chapter. It’s completely unintuitive given the terms, but it’s important for me to clarify. Public policy is the process of converting political intentions into outcomes in the real world. It focuses on the decisions of politicians that result in actual policy change related to such areas as a public healthcare system, defense forces, transportation, and education. Public policies come from all governmental entities and at all levels: legislatures, courts, bureaucratic agencies, and executive offices at national, local, and state levels. Smart city planning work must be viewed comprehensively through the lens of regulation. Teams must determine whether they need to heed any existing regulatory considerations and whether they may require the creation of new regulations. Rather than consider this a burden, new regulations may bring about better outcomes and foster more support. Of course, understanding existing regulations and making appropriate strategic choices also helps to avoid serious compliance risks.

Smart city planning work must be viewed comprehensively through the lens of regulation. Teams must determine whether they need to heed any existing regulatory considerations and whether they may require the creation of new regulations. Rather than consider this a burden, new regulations may bring about better outcomes and foster more support. Of course, understanding existing regulations and making appropriate strategic choices also helps to avoid serious compliance risks.