Chapter 7

Embracing Urban Innovation

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Examining what urban innovation really means

Examining what urban innovation really means

![]() Exploring ways to implement urban innovation

Exploring ways to implement urban innovation

![]() Discovering the purpose and value of experiments and hackathons

Discovering the purpose and value of experiments and hackathons

![]() Developing intriguing urban ideas into live projects

Developing intriguing urban ideas into live projects

The art and science of applying new ideas to solve urban problems has existed since the first human settlements. When confronted with an unrelenting and often unforgiving flow of challenges, city leaders throughout history have been forced to evaluate options, experiment with ideas, and deploy creative responses. Every day presents another hurdle to overcome, and many times it’s new and confounding. That’s the nature of running a city in the 21st century. Cities may be humans’ greatest invention, but they require exhaustive attention, maintenance, and support in order to thrive. With bigger and more complex problems, higher expectations from residents, and a sense of urgency in many areas, discovering and acting on new ideas —innovating, in other words — is being elevated as a priority by cities all over the planet. A city can innovate without having a smart city strategy, but it can’t have a smart city strategy without innovation. In this chapter, I discuss various aspects of urban innovation, including a few approaches to get results.

Defining Urban Innovation

In my experience, there’s often confusion and disagreement about the term innovation, so here are a couple of definitions to help you understand this topic:

- Innovation: Converting ideas into value

- Urban innovation: Discovering and implementing new ideas to meet city challenges

Okay, now that I’ve spelled out the definitions, let me talk about water.

All living things on Planet Earth need water, and wherever you find water, you’ll find life. To survive, humans need regular access to drinking water. In their early nomadic times, as they wandered, they would need to find streams, rivers, and lakes. Later, when humans began to settle in small gathering places, they needed to be close to sources of water. Wells were dug into the water table, which provided a reliable water supply. Cisterns were created that gathered rainwater. In other instances, where water was relatively close, it was transported by people carrying baskets and other containers on their backs or heads or in their hands. Later, animals were used to pull carts. In some parts of the world, water is still transported by humans and animals.

As human settlements grew, demand for water for drinking and agriculture also increased. Systems were required in order to bring larger volumes of water predictably from the source. To solve this problem, humans invented the aqueduct — an elaborate combination of tunnels, surface channels, canals, clay pipes, and bridges — to move water to wherever it was needed.

Aqueducts that covered short distances were used in the earliest days of civilization, beginning with the Minoans on Crete, over 4,000 years ago. More sophisticated, longer-distance systems were developed during the Assyrian Empire. Later, the Babylonians, the Greeks, and communities across Persia, Egypt, and China all constructed elaborate aqueduct systems, including communal drinking fountains.

Finally, it was the Romans who mastered the building of aqueducts. Ambitious projects overcame all kinds of difficult terrain, including engineering, to move water upward. Many forms of aqueduct construction could be seen across the Roman Empire. The water supplied not only all basic needs and agriculture but also large public baths, fountains, and private homes. Many remnants of these systems can still be seen, scattered across the landscape. (See Figure 7-1.)

FIGURE 7-1: The Pont du Gard Roman aqueduct, in southern France, from the first century.

Aqueduct systems were essential for enabling communities to grow and thrive. In particular, major Italian cities such as Rome were able to prosper over the centuries because of the regular supply of water. Aqueduct engineering can be considered one of the most important urban innovations of its time. Human ingenuity brought to bear on a pressing and essential need resulted in nothing less than a transformation.

Here’s a list of some of the most important urban innovations:

- Roads and railways

- Harbors and airports

- Electricity

- Skyscrapers

- The Internet

- Sanitation systems

- Traffic signals

- Street lighting

- Urban planning

- Drainage

- Parks

- The grid system

- Public transportation

- Telecommunications

Each one of these items, and many more (alone and together), has made cities smarter, and typically better, places to live.

Urban innovation now continues at an accelerated pace. In fact, you can’t separate this topic from the topic of smart cities. Urban innovation is largely driving the pace of change in cities.

Relying on urban innovation networks

Solving the problems of the world’s communities requires the participation of a wide range of stakeholders. It’s not possible for a local city agency to solve every issue: No single organization has the budget, time, or talent. The challenges are just too large, often regional, and highly diverse for any single entity to tackle. Solving these challenges today requires a network of participants. Fortunately, a movement of urban innovators in cities all over the world are rolling up their sleeves and making things happen. Disparate stakeholders are joining forces to solve some of the world’s most intractable urban issues.

Urban innovation networks are clusters of various people and organizations who are connecting and collaborating on solving challenges. They’re interested in, and invested in, game-changing, new ideas, often (but not always) technologically driven. These networks are trying to make a difference in areas such as sustainability, transportation, inclusion, climate, governance, equity and equality, public safety, waste management, and more. Fundamentally, efforts have one large-scale focus: improving quality of life (QoL).

Here are just a few of the areas where participants in urban innovation networks come from:

- Academia

- Vending

- Local government

- Regional and national governments

- Student

- General community

- Specialized institution

- Regional, national, or international organization

The ways in which these disparate players connect and collaborate are as diverse as the cities and participants themselves. An urban innovation network can be a formal organization with a charter and rules or an ad hoc collection of entities that tap into each other’s skills and resources as necessary. It can be centralized by way of city hall or a motivated vendor. Universities have been particularly active in building out urban innovation networks, to tackle a single-focus issue or a suite of challenges.

If humans are going to create cities that they aspire to live in, their future will be built on networks of motivated, empowered, and talented participants. Cities are now too complex and interdependent for any single entity to lead efforts alone. The best solutions won’t necessarily spring from government buildings (although a few will); instead, support and success for smart city efforts, powered by urban innovation, will come from entrepreneurship, the exchange of ideas, the synergy of resources, and the energy of a diverse community.

Creating urban innovation labs

Solving today’s tough urban problems in the years ahead will require a variety of new approaches. Albert Einstein, the German-born physicist, is reported to have said, rightly, “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” To create urban innovation, we humans will need new, dedicated processes and talent to experiment and test original ideas and technologies.

One approach is the creation of urban innovation labs, which are entities tasked with developing leading-edge ideas for a city’s most intractable challenges. The labs are typically physical locations that support the experimentation, testing, and — assuming success —deployment of new solutions. They’re laboratories of urban innovation.

There’s no agreed-on blueprint for creating an urban innovation lab. The first step for a city is to agree that such a lab has value and then to either build one or collaborate with an external party in delivering its value. Many cities create their own labs and house them in city-owned or -leased buildings. Others collaborate with private entities and universities that partner to provide capabilities as a service. Cities that support these labs share at least two common — and still quite rare — qualities: They have a higher tolerance for risk and are comfortable granting some autonomy and freedom to innovate to these innovation teams.

Urban innovation labs can work in alignment with smart city activities or they can be independent of those activities. Either way, their work is typically focused on pressing city issues. Their independence from the requirements to support core city functions gives them the flexibility to experiment and not be constrained by regular city operations. Regardless, the lab gets no free pass when it comes to abiding by all city rules and regulations.

To embrace urban innovation labs, cities must have a higher tolerance for risk. This is because innovation, by definition, is riskier. Specifically, innovators must be allowed to try strategies that have a higher likelihood of being unsuccessful. Being able to approach problems with this mindset increases the chance of a unique solution emerging and — in the case of a failure — creates continuous opportunities for learning. Unlike in the private sector, where some amount of experimentation and failure is expected relative to advancing new, proposed products and services, the public sector isn’t historically predisposed to this approach. Public officials have an enormous obligation to be fiscally responsible when managing taxpayer funds, and, with so many priorities to serve a community, the appetite for risky bets is always low.

It’s fair to say that the proposal for an urban innovation lab is a hard sell. That’s why you don’t yet see many of them. But the tide is turning: A broader recognition that innovation is essential to solving the world’s greatest challenges is helping communities and city officials recognize the benefits of paying more attention to, and focusing on, processes that are game-changing. In addition, the success of urban innovation labs in several cities is providing good evidence for making the case.

Implementing Urban Innovation

Even if cities don’t formally call it “urban innovation,” many agencies are engaged in some form of idea generation and development. For example, in a 2019 survey of 581 public officials from different governments in the United States, over 40 percent said they were experimenting with urban innovation. Agencies have to innovate — community needs and challenges aren’t getting easier. In fact, intense issue complexity and creative responses will be defining characteristics of most cities in the years ahead. It’s not even a matter of size or location — the need for innovation spans all types of cities. There’s pressure to discover new ideas, explore them, test them, and decide whether to implement them. The challenges of cities demand it. Urban innovation can be applied in every aspect of a city’s operations.

Though some local governments have formalized and developed multi-year innovation agendas, many have not yet made that decision. They certainly innovate, but they haven’t yet carved it out as a deliberate part of their city’s strategic plan, with an attendant set of approved processes. Of course, it’s fair to say that, for many, the absence of formality isn’t caused by a lack of enthusiasm. There are many legitimate reasons that plans don’t exist: insufficient budget amounts or a lack of time and talent or other, more pressing priorities. However, my guess is that, for most, the time will come for developing a formal urban innovation program. It’s a question of when, not if — and then a follow-up question of how.

Engaging in urban innovation means discovering and implementing new ideas to meet city challenges. So it’s okay to acknowledge that urban innovation may be part of many projects in a city. Lots of innovative staff are agents-of-change in their agencies. They also use innovative tools to implement and support solutions. Bravo to them! But urban innovation is also often understood to mean the process of trying new things in an experimental manner. Being experimental suggests, by definition, that the work has a higher likelihood of failure. That’s clearly different from engaging in work where the anticipated outcome is success. That’s what is expected from most projects: Identify a need, determine the budget, create a plan, and then perform and complete the work. For the purposes of the discussion in this chapter, urban innovation — the experimental kind — typically doesn’t follow that comfortable and predictable path.

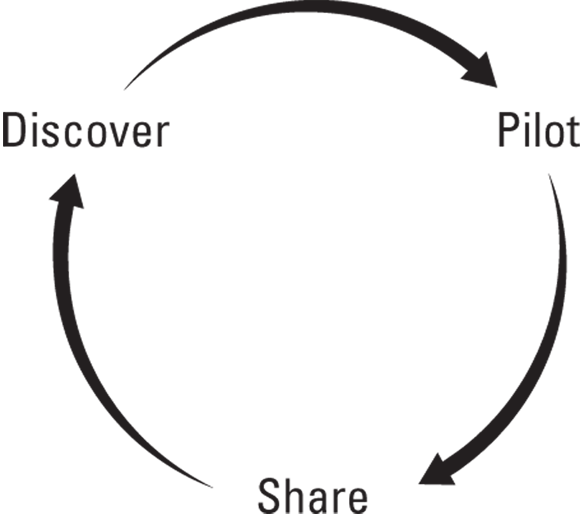

Here’s the general path for urban innovation:

- Discover: Understand the problem and engage in a process to find viable solutions.

- Pilot: Develop a small but sufficiently viable implementation of the solution to test.

- Share: Document and provide the insights gained from the discovery and pilot phases to a large stakeholder group, including internal and external parties.

There are many flavors when it comes to this sequence, but this is the gist of it.

Figure 7-2 illustrates the process. It’s a cycle because there may be a need to repeat it several times before a viable result emerges. I cover moving from an experiment to a project later in this chapter, in the section “Converting ideas into projects.”

FIGURE 7-2: The basic cyclical process of urban innovation.

Examining the discovery process

Let’s look at what triggers the discovery process. Remember that this phase concerns itself with both understanding the issue to be solved and the exploration of solutions.

At least seven triggers can act as an impetus for starting the discovery process, as described in this list:

- Required implementation (a new regulation, law, or policy, for example)

- Necessary upgrade to a process or technology

- Response to a community need

- Implementation of new service

- Solution to a specific problem

- Support of an urban innovation agenda

- Implementation of a project within a strategy, such as the smart city initiative

In this section, I'm mainly concerned with the last two triggers, which, for simplicity’s sake, I collapse into a single trigger. In your city, the innovation agenda may be the consequence of the smart city strategy or simply an agenda in support of advancing the city’s broad goals. Either way, the process is the same.

In Chapter 5, I discuss how a smart city vision is translated into goals. These goals then become objectives, which in turn typically manifest as projects. These projects trigger discovery work. An objective to reduce road flooding may be perfect for the urban innovation process because the solution is unknown and many new technologies may be worth exploring. You have to decide, case by case, what’s appropriate.

So you have a project that requires discovery. Now what?

First, ask yourself whether you fully understand the scope of the project, its objectives, and its metrics. If not, interview the teams responsible for the objectives as well as the project.

Now, I'm assuming that you have a good understanding of the scope of the project and that you’re now ready to engage in discovery. You have two main tasks:

- Investigate potential solutions.

- Determine whether identified solutions potentially meet your project objectives.

When it comes to carrying out your investigation, here are a few options to consider:

- Conducting a web search

- Talking to colleagues in other cities

- Tapping into professional networks

- Researching industry groups

- Consulting industry publications

- Searching an online solutions catalog

- Eliciting solution providers to submit their solution for consideration

After you’ve identified a short list of potential solutions, you might request an informal discussion with each of the potential vendors. The purpose of this meeting is to better understand their offering and compare it against your project objectives. Using a checklist is beneficial so that you can easily compare products against each other. Because this isn’t a formal elicitation process, the normal rigor of vetting the vendor and the product is less necessary (though you might choose that option). The experimentation and piloting process enable an understanding of the functions and performance of solutions.

Running pilots and experiments

I make a differentiation between pilots and experiments. Others may not.

A pilot is an effort that tests a solution with a decent expectation that it might be a candidate for later full deployment. Given that it’s defined as a small implementation — a few users, a limited geographical area, and a short time frame (three to six months is reasonable), for example — it should provide ample evidence to the project team that it’s worthy of further exploration and potential use.

An experiment is work that is highly speculative and risky. It’s usually done when the project team has a lower level of confidence that the right solution has been found. It’s also a more learning-intensive approach, and its timeline may be even shorter than a pilot.

Just to keep it confusing, some people also use terms such as proof of concept and prototyping to describe the same type of project methods. All are relevant, and the available literature goes to great lengths to describe all the subtle differences. Just know that each is a way to test an idea, a product, or a service in order to make informed decisions.

Though the overall approach to running pilots and experiments may be largely identical, my differentiation helps you set expectations for stakeholders. Also, an experiment may not be subject to quite the same rigor as a pilot. For example, in a pilot, the project team may decide to also test the training for the solution. In an experiment, the team may pass on the training and be hyperfocused only on the functionality of the potential solution.

A pilot and an experiment, hereafter called the innovation pilot, may follow the typical stepwise project methodology, such as the waterfall model, where the project is completed in the following five distinct stages and moved, step by step, toward an ultimate project launch:

- Plan

- Design

- Develop

- Deploy

- Test

A variety of stakeholders have differing interests in innovation projects. Solution providers, which can range from start-ups to large corporations, are often particularly enthusiastic about partnering with a city on an innovation project. This partnership can provide them with vital, on-the-ground test data and also be an opportunity to draw attention to their product or service. And, of course, the corporations are pleased that the work might eventually translate to a full sale. The interest in an innovation pilot for a solution provider may mean that it’s prepared to be accommodating on cost. At minimum, the costs should be low, given the limited scope of the work, and, in the best case scenario, the provider might be prepared to engage in the innovation pilot at no cost. This is certainly no guarantee, and is determined case by case. It’s also subject to procurement rules for your agency.

For the city, an innovation pilot provides insights into whether a solution is right for a specific challenge. There are benefits to being able to test in a real environment without a lot of risk in terms of costs and time lost, and it always helps to learn about the performance of a product and vendor in advance.

Other regional parties may benefit, by either participating in the innovation pilot or receiving any insights gained from the work. Participating means that costs can be shared and a larger variety of conditions can be explored. For example, a solution for public safety may be well informed by having several regional agencies participate in terms of data sharing and coordination.

Finally, as with all activities related to smart cities, collaboration between departments in a city agency is a proven approach to success. Having multiple, impacted teams engage in the innovation pilot provides essential data to inform the larger deployment; it improves learning and identifies potential gaps as well as provides the basis for achieving any decision consensus.

Setting up living labs

Urban innovation leaders may want to consider the development of a living lab for their pilot and experimentation efforts. In the context of a city, a living lab is a real-world environment, often in a defined geographical area, where community members and other stakeholders can either participate in co-developing solutions or experience an innovation pilot and provide feedback. Many stakeholders can participate and learn from these labs, including service providers, government staff, media, and constituents. In this way, they’re said to be public-private-people partnerships (PPPPs). Both the participation and feedback from partnering members have enormous value in helping to evaluate an innovation. The candid feedback from community members — typically, those who will be impacted by any new urban innovation — is particularly important.

A smart city with an urban innovation capability would be well-served to explore the development of a living lab.

Living labs have these benefits:

- Co-creation of innovation with various stakeholders

- Discovering uses, behaviors, and unanticipated consequences

- Encouraging the participation of citizen scientists

- Experimentation of different scenarios in a real environment

- Research opportunities for academia and other interested parties

- Evaluation of a pilot or experimentation from many different perspectives

Engaging in hackathons

To be successful when it comes to urban innovation, you need the input of many stakeholders. It’s a mistake to see it as the domain of a few dedicated folks. Assigning a team to innovation and not encouraging collaboration from disparate players can result in others believing that they can wash their hands of innovation by simply believing it’s the responsibility of a single team. You don’t want that. Sure, you may want a team that's designated to take the lead when it comes to innovation, but you also want to make it easy for lots of people to be engaged.

Hackathons and challenges are two creative ways to engage a broader community in the process of urban innovation. I discuss each one individually in this section.

What exactly is a hackathon? The word itself comes from the combination of hack and marathon. Straightaway, you might wonder why hack, which typically has a negative connotation, is being used here. Hacking does have a rather shady reputation when it comes to the cybersecurity world, because it’s used to describe the act of breaking the security of some product or service. You’ve seen it on the news, and maybe you’ve even been a victim, if someone hacked your email or bank account. However, the hack in hackathon doesn’t have that meaning. You can find several stories about its origin; I’m sharing my favorite here:

During World War I, planes returning from battle would land at their base having sustained damage from gunfire, such as in the fuselage, wings, and tail. Engineers on the ground used spare parts and parts from destroyed planes to fix the planes that were capable of returning to the skies. They would “hack” apart the broken planes to assemble new, reconstructed parts quickly — thus, the rise of the word “hacking.” In the modern context, it means throwing together a solution quickly and crudely, but in a way that works.

The -athon part of the word hackathon comes from the word marathon. It reflects that the event has a specific duration and that the activity is rigorous: hack + athon = hackathon.

But, again, what is a hackathon? It’s a private or public event that brings together solvers to work on one or more problems. Historically, these solvers have been software programmers, but that’s no longer the case. These events can attract all sorts of talent to solve tricky issues.

The event can last from a few hours to a few days; they typically don’t run longer than five days. Participants usually form small teams, dive deeply into the problems, and sometimes work through the night. (They often sleep at the event.) The intensity of those working on the problems results in full exhaustion by the time the event ends. A good supply of coffee, pizza, soft drinks, and other snacks is always served. (Hackathons aren’t famous for quality nutrition.)

Many hackathons are competitive. At the end of the event, a group of judges selects the top solutions and teams, and prizes are awarded. Participants gain satisfaction from creating useful projects and also the possibility of receiving cash or other rewards.

Over the past decade, cities have used hackathons to engage their communities in solving issues. Though building software solutions has largely dominated, these other creative events have been involved:

- Writing policies

- Cleaning up documentation

- Organizing data

- Drafting budgets

- Building hardware

Creating software solutions to solve city issues often requires city data. The emergence of open data, as discussed in Chapter 9, creates a superb intersection of value. Hackathon developers can easily access city data via the city’s open data portal, either by downloading data in a standard format or, preferably, a real-time connection called an application programming interface (API). I explain APIs in Chapter 8.

Many cities hold hackathons to draw attention to their open data initiatives. Providing the data in this way also enables many events to encourage participants to solve problems that interest them, rather than tackle problems the event imposes on them.

City-based hackathons are excellent platforms for community involvement. Though the practical outcomes may not always meet expectations, the networking, collaboration, learning, and civic engagement of the participants is often enough to make the events worthwhile. Sometimes, though, a brilliant solution may in fact emerge.

Here are a few quick tips for running your own hackathon:

- Make the invitation inclusive. Though the solutions may require software development, there are roles for lots of different types of people and talent. You can assist by splitting participants into diverse teams (unless they show up as a team).

- Find a suitable facility. You need a large, open space and, possibly, areas for sleeping. The size depends on the number of participants. On average, space to accommodate between 30 and 100 people is reasonable.

- At the event’s kickoff, describe the problems that need to be solved. Though keeping goals open is an option, focused hackathons often get better results. Solving the problems should be attainable in the allotted time frame.

- Offer plenty of food, drinks, and snacks. As I mention earlier, don’t expect much nutrition. Can I suggest throwing some fresh fruit into the mix?

- Invite dignitaries to attend at certain times. Having these leaders participate can boost morale and add cachet to the event. In my experience, having the mayor attend, perhaps at the start as well as later during the event, is extremely helpful.

- If permissible by your agency, consider acquiring sponsorship from local companies and technology vendors. This lowers the cost burden to the city but also allows for better facilities, food, and prizes.

- Ensure that plenty of power sockets are available. How embarrassing would it be to have this type of preventable problem?

- Ensure that the event has excellent Internet connectivity. This is an absolute must-have item.

For more great advice, check out https://hackathon.guide.

Participating in urban challenges

Finally, another type of event, similar to a hackathon, is the urban challenge. You don’t need to limit yourself to the constraints of a hackathon to engage different stakeholders in developing urban innovation. You can explore other options.

An urban challenge is typically a longer, more focused process. Distinct from a hackathon, it typically has the following qualities:

- Participation that comes from solving a single complex issue

- A longer duration, perhaps three to six months

- Larger rewards for winners and runners-up

- Participation from people all over the world

- Possibly one or more major sponsors from public and private sectors

- A large number of participant teams

The successful technology behind self-driving cars is the result of a challenge.

Check out www.challenge.gov, shown in Figure 7-3, a service of the United States government that works to engage citizens in competitions to solve issues of national importance. At the local level, San Francisco’s Civic Bridge (www.innovation.sfgov.org/civic-bridge) and Chicago’s Civic Consulting Alliance (www.ccachicago.org), are examples of solicitations for pro-bono talent to solve community challenges.

FIGURE 7-3: Examples of challenges at the US government site, challenge.gov.

Open innovation versus closed innovation

Both hackathons and urban challenges embrace the idea of engaging a wide range of participants. This concept, known as open innovation, functions as an alternative to conventional methods that limit participation only to specific people and groups. Intuitively, such a conventional approach is called closed innovation. The thesis is that, with open innovation, you can increase the volume of ideas and engage the best original thoughts from a broad and diverse group of innovators. This is particularly important when it comes to solving tough problems.

Open innovation is highly beneficial to cities because it can reduce the cost of research, bring novel ideas and practices into the mix, leverage existing innovation ecosystems, and encourage productive collaboration among diverse teams.

There are a few downsides to open innovation in a local government context. In the private sector, the main concern for organizations is being afraid of their ideas being stolen. For public agencies, the downside to open innovation is that it’s more complicated to manage. You may have to coordinate a large number of people and ideas. In addition, open innovation can be a lengthier process. You’ll determine the approach based on your needs.

Sharing urban innovation

In the process of urban innovation, you’ll create and document a lot of data and information. This output is valuable to a whole host of stakeholders, from city leaders to community members and from department heads to vendors and many others. At the conclusion of an innovation pilot, the core project team will likely present its findings. At minimum, the question arises of whether the pilot was a success, based on the desired outcomes. Information needs to be presented that supports the project findings as well as any recommendations stemming from the pilot. If the pilot didn’t succeed, you have to determine what lessons were learned.

The opportunity exists to share even more broadly. Consider making the results available to other communities, particularly those who are interested in solving the same problems as you. Find a platform that enables the sharing of urban innovation in your region or country. In the private sector, sharing the work of innovation isn’t generally embraced, because this work is highly competitive in nature. But in the public sector, where cities generally aren’t competing (with some exceptions, say, for talent), sharing ends up benefiting everyone. With the focus on quality-of-life improvements, shared urban innovation can help more people and can be magnified when applied at a regional level. This is what’s at the core of serving the public’s interest.

Converting ideas into projects

Fundamentally, an urban innovation program is about sourcing new ideas for solving intractable city issues. As I discuss in this chapter, piloting and experimenting with new ideas before full deployment is a smart risk mitigation strategy. But don’t lose sight of the intent. If an innovation pilot is successful, the opportunity exists to convert it to a full-blown project.

After the innovation pilot is complete, the team must document all its findings, and the results must be compared to the original objectives and desired outcomes. This work should make for some robust discussions. In the end, the team needs to determine, with supporting data, whether the innovation pilot was a success. If it has succeeded, further decisions need to be made.

A successful innovation pilot doesn’t automatically turn into a full deployment. For example, the project may have been exploratory or demonstrable only, or a way to gather more data for input into a higher-level decision. The project may also be lower on the priority list.

However, the innovation pilot may need to be moved to a full project. In this case, the effort will likely be moved to a project team or project management office (PMO). Any decision surrounding how a project is handled is the subject of project governance, a topic I discuss in Chapter 6.

If an urban innovation pilot results in an actual full-scale deployment and then goes on to solve what once was an intractable community issue, that’s the definition of success. Cities all over the world are quickly learning the value of urban innovation, pilots, and experiments. This work isn’t restricted to large and wealthy communities. All types of communities are seeing the benefits of applying rigor to eliciting and identifying new ideas.

History is replete with these game-changing innovations in an urban context. Humans have solved many intractable issues over several thousand years (though many more remain to be solved). The results have been nothing less than miraculous, enabling them to design and build dense urban environments such as the greater area of Tokyo, Japan, which now is home to over 35 million residents.

History is replete with these game-changing innovations in an urban context. Humans have solved many intractable issues over several thousand years (though many more remain to be solved). The results have been nothing less than miraculous, enabling them to design and build dense urban environments such as the greater area of Tokyo, Japan, which now is home to over 35 million residents. In developing an urban innovation lab, city leaders must emphasize the focus on experimentation, learning, and efficiency. Though these labs can exist independently of a smart city strategy, there appears to be important value in determining whether they can accelerate and improve the performance of smart city efforts. Aligning their goals may be a good approach for some agencies.

In developing an urban innovation lab, city leaders must emphasize the focus on experimentation, learning, and efficiency. Though these labs can exist independently of a smart city strategy, there appears to be important value in determining whether they can accelerate and improve the performance of smart city efforts. Aligning their goals may be a good approach for some agencies. The entire urban innovation process must align with the vendor engagement and procurement rules of your agency. Don’t even begin to think about initiating this work until the permissible rules are established. In government agencies, these rules are specific and enforceable. Make sure your legal, financial, and procurement team leaders are all onboard and have formally approved the approach.

The entire urban innovation process must align with the vendor engagement and procurement rules of your agency. Don’t even begin to think about initiating this work until the permissible rules are established. In government agencies, these rules are specific and enforceable. Make sure your legal, financial, and procurement team leaders are all onboard and have formally approved the approach.