Chapter 12

Smart Cities and the Symbiotic Relationship between Smart Governance and Citizen Engagement

Tori Okner1 and Russell Preston2

1Senior Associate, Principle Group, Boston, MA, USA

2Design Director, Principle Group, Boston, MA, USA

Objectives

- • To become familiar with smart governance through emerging best practices stakeholder engagement

- • To become familiar with the importance of placemaking and human-scaled design with respect to smart governance

- • To become familiar with the importance of city planning on the neighborhood scale that connects sincerely with local places

- • To become familiar with how to organize an engaging, community-led planning process

- • To become familiar with how to make informed decisions about technological solutions that have emerged through community discussions and planning.

This chapter recognizes that cities are at the forefront of innovation and are increasingly competing for scarce resources. It suggests that for smart cities to succeed they must facilitate human connection. This can be achieved through smart governance, circumspect implementation of the tenants of smart cities, along with human-centered planning and design. The symbiotic relationship between citizen engagement and smart governance is explored through a case study on Somerville, Massachusetts. Lessons learned and broad recommendations are then posted for readers' consideration.

12.1 Smart Governance

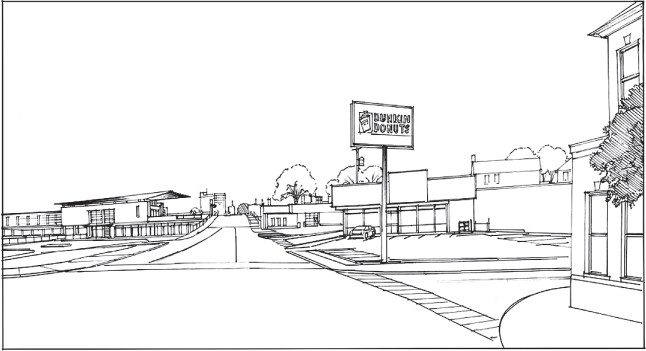

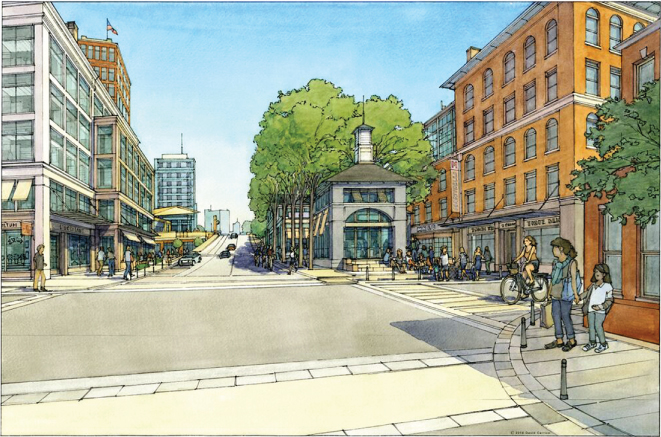

Today, as the world's population continues to urbanize, demands on cities are ever increasing. Cities must plan for the impacts of climate change, the public health and economic burdens of sprawl development, and the increasing consumer choice to live and work in mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods, and do so while competing for limited resources. The old trope that necessity is the mother of invention has proven true in cities, where, in the absence of national leadership, municipalities are at the forefront of innovation on the issues of the day. From tackling climate change through the C40 to the Urban Food Policy Pact, cities are at the forefront as Benjamin Barber proffered when he imagined what If Mayors Ruled the World. Truly, the “optimism and opportunity is coming up from cities…that's where the real action is….it is a global phenomena” [1]. Municipal leaders are striving to do more with less, and while technology can facilitate that, success depends on smart governance (Figures 12.1 and 12.2)

Figure 12.1 Union Square Prospect Street, no build condition.

Source: Courtesy of David Carrico.

Figure 12.2 Union Square, Prospect Street, proposed.

Source: Courtesy of David Carrico.

Truly smart governance is more than “public policy keeping pace with technological developments” [2]. Technology alone will not improve our cities. Municipalities interested in embracing the tenants of smart cities – from smart economy, mobility, and environment, to smart people, living, and governance – must effectually engage the local citizenry and leverage technology to do so. Perhaps even more so than the need for research and innovation, the success of the smart cities depends on circumspect implementation.

The application of technology to support the creation of more human-scaled development has immense potential. In the last hundred years, technology has affected the way we organize ourselves and our cities more so than at any other time in history. Municipal water and sanitation systems have decreased the incidence of diseases. The elevator allowed us to reach the sky. The advent of personal automobile and postwar industrialization of the housing market allowed us to supply the American Dream to hundreds of thousands of families. Until only a few decades ago, these last two technologies were perceived as great steps forward; they have since been linked to dozens of social, environmental, and financial catastrophes. The technologies that supported suburban land use also allowed the fundamental pattern for how cities function to be disrupted with unintended consequences. Contemporary use of technology must learn from the past to support the growing challenges cities face today and facilitate sustainable, resilient growth. Smart solutions will be needed to support this shift toward walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods.

Cities that learn to attract growth through the creation of authentic places will be more competitive than those that do not.1 “The future of thriving and resilient cities is not led by sustaining or innovating around infrastructure and services, but by building the capacity of communities to drive their own shared value – to sustain Placemaking” [3].2 This analytical and objective approach to city building was pioneered by William “Holly” Whyte and popularized in his book City: Rediscovering the Center. The not-for-profit Project for Public Spaces has expanded on this work demonstrating that projects focusing on the improvement of social interactions in public space can be the catalyst for investment, change social behaviors, and help to build better connections in a community, oftentimes leading to further improvements. Proper organization of emerging technologies for transportation, communication, development, and finance is the key to this puzzle. It is essential that the technologies support human-scaled details that make these authentic places work. Citizen engagement is crucial to achieving this balance and to understand the unique details of a place.

Early visions of the smart city were built on urban modeling software. Urban dynamics, computer simulations, computer-based urban simulations, predictive city simulators – these efforts to apply system dynamics to urban centers have now largely been dismissed due to their severe constraints [4]. Historically, these constraints have been primarily the limitations of computing power, access to large amounts of current data about a place, and the reliance on incorrect assumptions when designing the modeling. In the early 1970s, these constraints led many cities to fundamentally question the recommendations that these models produced.

Natural metaphors later came into vogue pioneered through the writing of Jane Jacobs, Christopher Alexander, and others. The common element in these foundational works is the idea that cities function as ecosystems with patterns and feedback loops much like those found in nature. This thinking has led to revisions in system dynamics that represent cities now, to more accurately capture the complexity that these ecosystems possess. As technology has advanced and large amounts of real-time data have been opened up for analysis, we are finding that the dynamic modeling of a city's performance is again helping assist community leaders with decision making.

Citizen engagement insures that hyperlocal insights can be leveraged to inform the system and identify leverage points for community improvements and growth. Smart governance is needed to facilitate this fine-grained engagement and to maximize the use of smart cities technology. There is, in short, a symbiotic relationship between citizen engagement and smart governance. To effectively use technology, planners must recognize that cities are made up of a network of individual neighborhoods – neighborhoods that have different problems, opportunities, and constraints. Cities are polycentric and technology can facilitate these local systems, because “by giving lots of touch points across the city, making the government more visible, you thicken the mesh of democratic engagement” [1]. Smart cities will enliven the nodes, or touch points, but smart governance is necessary to ensure the data are activated; smart governance ensures that data-driven management does not rest on the false certainty of analytics but is informed by citizen engagement [1].

12.1.1 Smart Governance and Smart Cities

Today's smart city is understood to be a place “where information technology is combined with infrastructure, architecture, everyday objects, and even our bodies to address social, economic and environmental problems” [4]. However, smart cities are a means to an end – a more sustainable and vibrant community.

The diffusion of digital technology in the public realm, specifically Internet-based technology, has lagged far behind the private sector. Nevertheless, expectations for “E-government” reflect the heightened expectations for efficiency and transparency enabled by technology in other realms of private life. While traditional government service was based on face-to-face interaction with constituents and paper trails through bureaucracy, there is now less tolerance for inefficiency. Indeed, there is the “expectation of networked delivery” even in governance [5]. There has been a culture shift due to access in technology elsewhere; there is a desire for more immediate access to the information, both for more modern customer service in constituent services and for more open government [4, 6]. Stephen Goldsmith, Professor of Practice at the Ash Center and Director of the Data-Smart City Solutions project, observed that technological tools – from cloud computing to mobile and data mining tools – provide a “breathtaking opportunity” for change if governments embrace them [1].

Where cities are becoming smarter and more sustainable, it is often in response to the demands of their constituents. According to the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School, “people are strengthening their relationships with governments to improve their lives in unprecedented ways…Individuals and groups at the local level are what drive it (civic innovation): they're harnessing access to data and technology to redefine how we interact with where we live” [7].

12.1.2 The Role of Planning & Design

The daily experiences of a city's population represent an often-untapped source of knowledge about how the city could be improved. Tapping into this knowledge base is essential for smart governance. Historically, planning departments have been the primary channel for harnessing this knowledge for the public good. Yet, it is difficult to determine if the facet of the public participating in planning efforts truly represents the issues and desires of the community at large. Smart cities can better utilize information and communication technologies to connect with stakeholders during planning efforts with the objective of bringing broader participations and more input into the creation of these plans. Robust public participation leads to the creation of more authentic plans that are easier to implement. Smart governance can benefit greatly by establishing real-time planning feedback channels within their neighborhoods.

Today, a city needs to be considering how it can improve its streets in 5 years, develop new transportation options in 20 years, and establish the framework for reinvestment over the next 100 years. Municipal planning is essential to envisioning the possibilities. Smart governance empowers citizens to answer the questions and in turn prioritize which technologies are essential to fulfilling a city's short- and long-term goals. Cities that tend to be the most economically sound plan for the future. When a city has a clear physical vision for its future, has organized its capital budget to tie directly to projects and programs to implement that vision, and establishes feedback channels to monitor the progress, it is evident how powerful a systems approach to economic development can be. The technology of smart cities can support the greatest of economic development opportunities and the fundamental purpose of cities, to facilitate the gathering, meeting, and collaboration between humans [4].

Planning cities is never complete. Neighborhoods need to deal with new conditions that emerge every day. Smart cities have the opportunity to deploy and facilitate dynamic communication with their citizens so that planning can occur in real time. Static reports and cumbersome master plans do not help municipalities create healthy communities in the ever-changing economic, environmental, and social world we now live in. Planners need to help communities establish their vision and facilitate ongoing dialogue, react, and learn with each step toward fulfilling that vision.

Once a city establishes dynamic communication channels, planning changes from a linear, government-led process to one that is much more collaborative and iterative. This dialogue leads to a more open design process that can accommodate greater participation from the public in a productive and enjoyable process. The technology being deployed is not complex but when coordinated well can produce a platform that leads to more genuine discussions between neighbors and city officials. This collaboration allows for more sincere plans to be developed that neighbors will be proud to help implement and pleased to live with the results.

12.2 Case Study – Somerville, Massachusetts

12.2.1 Slumerville to Somerville

Lauded as one of the most influential cities in the country and the best-run city in the Commonwealth, Somerville is home to nearly 79,000 in just over 4 square miles [8, 9]. It is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the United States. Situated a mere 3 miles from Boston, it has emerged at the vanguard of urban leadership, recognized as an All-America City three times [10].

Over the last decade in particular, from the Boston Globe and Boston Magazine to the Huffington Post and The New York Times, article after article debates whether Somerville is the new Brooklyn, the pox of Millennials on the town, the loss of affordable housing, and the emphasis on all things local. Somerville is characterized by the vibrancy and tensions of the postindustrial immigrant community, artist and makers, and young professionals living in the densest city in New England. Recognized as one of the 100 Best Communities for Youth, Somerville is a radically different place today than it was even 10 years ago [11].

Through the 1960s, Somerville was a transit hub and largely industrial, hosting, among other firms: a bleachery, glass works, ice, tube and a safety envelope company, Sears Roebuck and Company warehouse, and a Ford auto assembly plant [12]. A period of deindustrialization and depopulation followed the closing of most of the industrial fixtures in the succeeding decades and the nickname Slumerville took hold. During the same time, a live-work artist development brought new life to a former A&P complex, becoming a model for similar projects around the country and sowing seeds of the creative economy now thriving in Somerville. Tensions of gentrification began with the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority's expansion of the Red Line from Boston in 1985.

12.2.1.1 Professionalizing City Hall

To some, it seemed evident that development pressure was driving decision making in City Hall; Slumerville was known for corrupt government. Indeed Lester Ralph, Mayor from 1970 to 1978 ran on a campaign to “clean up Somerville.” While there had been “a push to professionalize City Hall” beginning with his predecessor, the battle for Assembly Square – a large redevelopment site – revealed a legacy of fiscal opportunism that continued through the millennium.

Somerville is now experiencing two very different approaches to economic development. The first is based on the large-scale, both physical and economic, slow moving, private and public development projects that attract large employers. The second is the small-scale support of a growing community of entrepreneurs, makers, and artists who are building a vibrant creative economy within the network of postindustrial properties found throughout the city. The first is akin to big game hunting, while the second is akin to more economic gardening – both have been successful. The construction of the Assembly Square subway station brought approximately 4500 new jobs to Somerville when Partners Healthcare commenced development of a new corporate headquarters adjacent to the station. Greentown Labs, part of the creative economy centered in Union Square from 2011 brought $97 million in funding to the various start-ups housed within the business incubator space. Ranked the most bike-able community in the Northeast and one of the top ten biking and walking scores in the nation, Somerville understands sustainable transit fuels the local economy [13, 14]. As the Boston region continues to grow, it will be strategic to continue to support these distinct economic development strategies and, even more importantly, make sure that the two strategies work together collectively.

Mayor Curtatone

The last decade of change has been shepherd by Mayor Joseph Anthony Curtatone. Curtatone served as an Alderman in the City of Somerville for 8 years before becoming Mayor in 2004, at the age of 38. He was a popular-at-large Alderman, said to bridge Somerville old timers and new progressives.

As Alderman, he was chair of the finance committee. As he explained, “We weren't managing for results…we had a budgetary process where nothing was aligned with outcomes or measures…there were no goals and objectives…there was no accountability. No transparency…we would make decisions on a crisis basis” [15]. The City of Somerville relied on a traditional line item budget until Curtatone led the transition to a performance-based budget.

In the spirit of collaboration with civil society that Curtatone is now known for, he engaged Harvard students to help revamp the city's budgetary process. CommonWealth Magazine, a political observer, explained, “This curious collaboration – all the more striking because of Harvard's rarified reputation and Somerville's sometimes unsavory past – was designed to introduce to the city a new form of financial management known as activity-based budgeting” [16].

Managing for Results

As a Mayoral candidate, Curtatone ran on a platform of management reform [17]. He sought out best practices in the public and private sector and aimed to apply them to municipal government [15]. One of the primary goals was transparency, as emphasized by the budgetary reform.

In Somerville, as in other urban centers, “citizen expectations of innovation in public services continue to grow, while budgets shrink” [4]. To improve citizen services while working to bring the city's budget from the red, Curtatone focused on data-driven management, looking to revolutionary programs such as CompStat in New York and CitiStat in Baltimore [17]. Soon after Curtatone entered office, Somerville became the first city in the United States to operate a 311 constituent service center and Connect CTY (also known as a reverse 911) mass notification technology [18].

In Smart Cities, Anthony Townsend acknowledges the benefits of implementing data-driven management “as a triage tool for stretching scarce city resources” [4]. However, he warns against seeing it as a holy grail – citing the exposure of police maneuverings to affect CompStat as one cautionary tale. To prevent such manipulation, Townsend recommends that data need to be “sufficed throughout” City Hall, a notion Curtatone continues to champion.

SomerSTAT

Arguably, SomerSTAT, Somerville's data-driven performance management system, served as a transition technology, introducing a smart city lens that is now seen to be “embedded in the culture of (City Hall)” [19].

SomerSTAT is described as an

an initiative that helps Mayor Curtatone supervise the work of city departments and use timely data to inform decision-making and implement new ideas. Four SomerStat staff study financial, personnel, and operational data to understand what's happening within departments. Then, in regular meetings with City department managers and other key decision-makers, SomerStat helps to identify opportunities for improvement and then track the implementation of those plans. The meetings have become an ongoing conversation among city managers on where the city should be headed. Each meeting allows city managers to better understand how the City can streamline and improve its services to its constituents [17].

While the SomerSTAT team initially collected and analyzed data, they did not see themselves as “masters of the data,” but as facilitators leading a collaborative process [20]. Rather than take a “gotcha STAT” approach to data collection, Skye Stewart, current Director of SomerSTAT aims to see the total operations across departments in City Hall, positioning the team, “to identify the pain points across all departments” [20]. Indeed, George Proakis, the Director of Planning for Office of Strategic Planning and Community Development (OSPCD), observed that “STAT has let the Mayor build a very nimble Mayor's office. Previously, there was no interdisciplinary policy staff” [19].

ResiSTAT, a data-driven decision-making program, brings SomerSTAT out into the community both virtually and through regular community meetings. Rather than pushing data out, touting achievements from City Hall, it is designed to strengthen residential ties to City Hall and serve as a two-way process. Data on neighborhood level issues, from waste disposal and snow removal to the city's first report on wellbeing and the municipal budget, are presented online, through a website, listserv, active blog – the “online community forum” – and biannual ward meetings [21, 22]. By “empowering citizens with data” and making Alderman, city staff, and often the Mayor available at meetings, Somerville facilitates active engagement down to the street level. Decision making through ResiSTAT set the stage for the neighbourhood planning that Somerville is now known for, the smart governance practice reflects a culture “pickled in the idea that transparency is king” [23]. It is a prime example of an innovative government program that “will create new ways for citizens to make their voices heard, giving them the ability to provide input into regulations, budgets, and the provision of services” [6].

12.2.2 Planning Somerville

12.2.2.1 SomerVision

When Curtatone entered office, he ushered in an era of governance that strove “to be abnormal.” SomerVision, a community-based approach to urban planning and the City's first comprehensive plan, is one of the cornerstones of Curtatone's abnormal approach. It focused on creating shared values and measurable goals until 2030. Lauded with the Comprehensive Planning Award for a municipality over 50,000 population by the American Planning Association Massachusetts Chapter (APA-MA), it was developed over 3 years by a 60-member steering committee and supported by the OSPCD; it is the guiding document for decision making in Somerville [24]. Monthly Steering Committee meetings, a series of community values workshops, showcase events to review the draft plan, a widespread public survey, and discussions through ResiSTAT meetings fostered a strong sense of community ownership. The language of the goals, policies, and actions outlined are the result of the public process, largely unedited by City Hall.

The implementation strategy, including a map and measurable targets on housing, job creation, open space, transformation areas, and transportation, ensure that SomerVision sets measurable goals and a way to evaluate progress. These targets began with back-of-the-envelope calculations that evolved through an analysis of a wide range of variables [25]. Today, SomerSTAT uses SomerVision to evaluate the work of the OSPCD, but perhaps more critically, OSPCD is increasingly trying to use the STAT team as a resource to build out their analytics. The SomerVision process generated tremendous community feedback. In the years since it was published, the City has grappled with how to quantify the results of their robust commitment to public participation; a commitment that continues to deepen and evolve.

12.2.2.2 Somerville by Design

The accountability and transparency Curtatone trumpets extend to a public-engagement model described as “outreach–dialogue–decide–implement.” This process is distinct from the “decide–present–defend” model used by planners for decades. OSPCD sees it as a fundamental shift, a “new method for planning (that) acknowledges that the best results usually occur when informed residents collaborate with public officials to establish a vision for their neighborhood's future” [26].

Much like SomerSTAT led to ResiSTAT, bringing data-driven decision making into the community, SomerVision led to Somerville by Design (SBD), urban planning at the neighborhood level. An iterative approach to community-led planning, the SBD process is interactive and relies on a few tried and true strategies: (i) grow a crowd – crowdsource and encourage regular participants to bring new people in; (ii) bring meetings out into public space; (iii) translate – build a diverse crowd; (iv) use feedback loops – review previous decisions made through public process; (v) create interdisciplinary teams – work with consultants with complimentary expertise that balance out the skills on staff; and (vi) get speedy results – upload designs and output in real time to build on momentum from public meetings [27].

A recent process diagram of SBD, created by SomerSTAT and recognized by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, Boston's regional planning agency, as a leading practice, emphasizes that community process begins without a preordained plan, solutions are crafted through an iterative feedback loop in which problems are identified and best practices and new ideas are explored before arriving at a solution. Decisions are made in coalition.

City Hall departments have been reorganized as a result of SBD, ensuring municipal staff work in teams, not silos, to address the multidisciplinary challenges inherent in sustainable development. The SomerSTAT framework is integrated early on, providing a valuable, data-rich, feedback loop. For smaller cities, such as Somerville, city departments can have a greater impact when they work across departments in multidisciplinary teams that are organized around specific physical boundaries, such as neighborhood by neighborhood. With each new neighborhood that the SBD approach takes on, departmental silos weaken, and interdepartmental teams emerge to address the challenges inherent in the type of sustainable development the community is promoting for their future. The citywide integration of SomerSTAT has provided a valuable, data-rich, framework for this planning and feedback loops.

SBD is orchestrated in collaboration with an impressive breadth of citizen activists. The gear work behind SBD is made transparent through the charrette process to engage stakeholders quickly and meaningfully.3 Novel ideas are tested through Tactical Urbanism4 – short-term action to test long-term planning ideas – allowing innovative or misunderstood projects to be vetted by neighborhood stakeholders.

One of the key elements of the SBD planning method is the facilitation of a constructive and critical discussion with stakeholders that informs the ongoing improvement of the process. Each neighborhood planning effort is approached with a similar strategy, but the specific engagement tools are calibrated to the unique neighborhood needs. This constant improvement of the process and quick ability to adapt is a key example of how Somerville's smart governance is helping change the way neighborhood planning is done today.

Neighborhood Planning

In anticipation of the construction of seven new Green Line subway stations, Somerville launched a series of station area planning efforts in 2012. The first of these plans, Gilman Square, was the testing ground for this approach to planning. The planning process had a number of objectives – most notable to ensure that the local community had strong control over the future of their neighborhood as development pressure increased with the oncoming transit. The Gilman Square Station Area Plan went on to win the Congress for the New Urbanism New England's Urbanism Award for its innovative public-engagement methods as well as it visionary plans for the future station area.

Close interaction with the local community allowed the planning team to collaborate with several long-time property owners. The resulting plan creates a new public square at the intersection of three of the neighborhood's most important streets. Once the station is constructed, it will open directly onto this new Gilman Square resulting in the creation of a remarkable new public space that will include both public and private redevelopment projects, a new park, and prominent civic tower (Figures 12.3 and 12.4). In order to accomplish this feat, land trades between public property, both street right of way and existing open space, and private land will need to occur, new streets must be constructed, and the city and the transit agency will need to work in close coordination. This complexity would not be possible without a shared vision established though the SBD process fueling years of implementation ahead.

Figure 12.3 Gilman Square.

Source: Courtesy of Russell Preston.

Figure 12.4 Gilman Square, rendering of new public square abutting the proposed Green Line MBTA station.

Source: Courtesy of David Carrico.

Prior to the SBD Gilman Square process, no one expected this type of result. No one had considered a new civic space, let alone discussed how one might be built. The SBD method was able to uncover real hidden value for the community. Exploring value creation opportunities that change the public right of way has now become a common task in all neighborhood-planning projects.

In Davis Square, an existing transit-served neighborhood in Somerville, public space is short supply and an important public amenity that the city was looking to improve. While researching previous planning efforts, the Somerville by Design team tackled an unsuccessful, previous plan to convert a small public parking lot into a new plaza (Figure 12.5). In the spirit of Tactical Urbanism, the team decided to resurrect this idea and temporarily convert the space during the course of the multiday design charrette (Figure 12.6). The 12 parked cars that are there most days were removed in exchange for food trucks, live music, and circus acrobats (Figure 12.7). With the installation of comfortable seating and ongoing programming, it was only a matter of minutes before local residents began to use the new public space (Figure 12.8).

Figure 12.5 Davis Square, Cutter Plaza existing conditions.

Source: Courtesy of Dan Bartman.

Figure 12.6 Davis Square, Cutter Plaza pop-up plaza 1.

Source: Courtesy of Russell Preston.

Figure 12.7 Davis Square, Cutter Plaza pop-up plaza 2.

Source: Courtesy of Dan Bartman.

Figure 12.8 Davis Square Cutter Plaza image build out.

Source: Courtesy of Urban Advantage.

The plaza was not intended to be a spectacle. The team used it to attract the public into the planning process while testing the idea of converting parking to a public plaza permanently. By locating the studio space for the charrette in an empty storefront adjacent to the pop-up plaza, the planning process drew stakeholders who normally do not attend planning events into the creation of a long-term vision for their neighborhood. Through traditional public meetings, plan presentations, and town hall style debate, the previous public review of the proposed plaza was unsuccessful. Tactical Urbanism, coupled with crowdsourcing tools such as Twitter and Facebook, enabled the team to produce the pop-up plaza in a few weeks and to facilitate a conversation about the space in real time. Together, these tools allowed for a more sincere discussion about what the plaza could do and how it could serve the neighborhood resulting in overwhelming support of the permanent conversion of the parking lot to a pedestrian plaza.

The creative class that resides at, works at, and visits Union Square, another Somerville neighborhood, has made it one of the Boston region's most coveted. It is a center for the arts. It houses one of the country's largest maker spaces, Artisan's Asylum. It will also be one of the first neighborhoods to have a new Green Line subway station constructed. Tensions are high in anticipation of this new transit. In 2014, the city launched its most intensive neighborhood planning effort to date to establish a clear vision for the community in advance of the rail arriving.

In addition to addressing concerns about the potential radical changes to the community's character that the transit access could create, the neighborhood planning was tasked with creating a vision for more than 40 acres of land identified by the city's comprehensive plan as transformation redevelopment. How do you accommodate new transit-oriented development to take advantage of the new subway station and plan for the creation of a regional job center with millions of square feet of new development, all while preserving the authentic character of an innovative and art-oriented community? This question would test the limits of what was possible with the smart approach to planning that is SBD.

In Union Square, the planning team expanded on the typical SBD approach in four phases. The first is coordinating not only the planning team but also key members of the local community. Several events were hosted to crowdsource how to plan with the community; the idea is to plan for the planning together. This effort aims to educate the community on the process, ask how it can be made more sympathetic to local neighborhood conditions, and reiterate that there will be a beginning, middle, and end.

A small group of “community connectors” were organized in Union Square. Their role was to utilize their existing communication networks – through their various blogs, websites, Twitter, Facebook, and email lists – to push the planning team announcements further. This group also included the busybodies that every neighborhood has – people who know everyone, talk to everyone, and are generally the nods in the social fabric of the community. Supporting this naturally occurring communication network in the real world with digital assets allows the planning team to reach wider and deeper into the community than is typically possible. When you answer the “who, what, when, where, and how” questions together with the community, trust is easier to establish and it allows for a more genuine understanding of the community.

The second phase in Union Square consisted of helping the community establish a vision for their future through a series of community workshops. The community braved the worst winter on record to help make a better plan. Dozens of neighbors attended a neighborhood walking tour of Union Square on a Saturday morning at 7 a.m. in January with below-freezing temperatures and 2 ft of snow on the ground (Figures 12.9–12.11). They worked together in a space without heat but with translation services in four languages, conducting visioning and community mapping exercises. Long lauded for their facility with community engagement, mapping has become a much more powerful tool with the use of Google Earth and mobile apps that bring the technology to constituents to manipulate.

Figure 12.9 Union Square, walking tour.

Figure 12.11 Union Square, out in the cold.

The third phase was hosting a multiday design charrette. The key is to bring the designers to the community by setting up a temporary studio where they are able to receive real-time feedback from stakeholders. The charrette concluded with a comprehensive pin-up of all the ideas drawn and developed. Setting up a fully functional design studio in a temporary space that can support the work of dozens of consultants for a week used to be a much more expensive undertaking. In Union Square, the studio took place in a recently vacated post office. By utilizing inexpensive printers, cellular Internet hot spots, and cloud file-sharing services, an old post office was transformed into a fully operational design studio in only a few hours. The technology that allows for multiple consultants, from different firms, to plug into the studio instantly did not exist 5 years ago. Integrating this technology into the process has allowed for resources to be reassigned from administrative cost to higher value programming such as Tactical Urbanism installations or broader stakeholder engagement. This use of project management software and cloud services also allows the city to select a network of consultants to work collaboratively without the need for cumbersome project administration.

The fourth and final stage is to capture all the discussions that folks have following the charrette by hosting a series of plan open houses. These events usually have live music, local food, and a casual atmosphere to encourage discussion. They are designed to be fun events. In Union Square, one of the open houses was held in an underutilized parking lot transformed into a public courtyard with food, seating, and a bike repair kiosk. During the open house, new and refined plans are posted, encouraging conversation both between stakeholders and the planning team and among neighbors. At this stage, it becomes clear which ideas the neighborhood has embraced as their own that, irrespective of the plan document, will take on a life of their own.

These open houses conclude with the publishing of a draft plan, which is open for public comment online, beginning another discussion with the community as detailed elements of the plan are debated through various threads. This phase of the process usually includes another tactical intervention demonstrating several improvements conceived of in the plan. This type of short-term action helps keep what can be a long process for the public fun and interesting while providing the planning team a last point of feedback before publishing the final plan.

The draft of the Union Square Neighborhood Plan received the Comprehensive Planning Award from the American Planning Association's Massachusetts Chapter in 2015 further demonstrating the impact that this innovative approach to neighborhood planning is having on the region. The SBD method would not be possible without the deep support of the city's leadership at the highest level, their commitment to an iterative approach that is not always predictable, and their use of emerging technology to seamlessly connect the project team to the selves and to the community.

Technology in the Somerville by Design Process

Proakis says Somerville is continually looking to technology to support a seamless dialogue, where “technology isn't replacing that (community) interaction but augmenting it so it becomes more meaningful.” In 2014, Proakis was awarded Planner of the Year by the Massachusetts Chapter for the American Planning Association. Proakis believes that “as a City we do more public communication using technology than anyone else I know” [19].

Technology is used both in the service of community-led dialogue and to facilitate the design process. The municipal team relies upon web-based technologies to interface with one another and the Somerville citizenry, enabling collaboration that, while rooted locally, attracts talent beyond the city limits. Consultants work across platforms, using Asana to manage projects with the City Team and Slack, an instant messaging application, to communicate internally.

At the center of the Somerville by Design, internal process is Dropbox. The cloud-based file-sharing services have allowed the city to establish project folders that team members from multiple offices and, sometimes, spread all over the country to seamlessly share files with simple version control. This virtual server is the bedrock of the method, and without it, this approach would be far more difficult.

A typical planning department's familiarity with graphics software stops at PowerPoint. The use of Adobe's Creative Cloud has been another cloud-based solution that has allowed for the city's planning staff to not only work in the sources files created by the consultant team but also to become key contributors to the creation of deliverables by using InDesign, Illustrator, and Photoshop collaboratively with consultants. The use of this platform is now required by all offices working on SBD projects. Somerville has invested in their staff in a smart way by placing them at the center of creating the multiple deliverables required by this iterative planning process.

In additional to the internal project management and production technology, the integration of a number of externally focused platforms has been needed to further support this sincere approach to placemaking. In order to truly create a transparent planning process, the planning department needed to set up their own communications platforms so that information could be transmitted in real time to the various stakeholders engaged in the multiple planning efforts occurring throughout the city. OSPCD hosts a WordPress Blog and uses the freedom of the blogosphere and an SBD Twitter account as disruptive tools both to push information out in real time and as a tool for engagement. They also developed and managed their own MailChimp email list; most departments and even teams within their own departments have their own listservs [28].

All these tools were activated outside the City's Communications Department and established communication channels. OSPCD staff were not experts in communications, but by integrating this technology into the SBD method they have acquired, sometimes through trial and error, the essential communication skills needed to maximize the impact of these social media platforms. These tools now facilitate and promote honest dialogue about the future of the city.

Establishing these communications platforms has allowed for the increased use of online surveys and polling to further understand the community's preferences. These platforms have varied from free series such as Survey Monkey to premium ones such as MindMixer. The use of these tools requires that OSPCD juggle sometimes a dozen accounts at a time, with some staff spending up to a quarter of their time on outreach [28].

Furthermore, OSPCD staff seek emerging software to meet their needs. For example, Senior Planner Dan Bartman spent years looking for a web-based platform to gather public feedback through the planning process. Through Internet searches and listserv queries, and after rejecting possibilities that would need to be rebuilt from the ground up and adapted, he discovered MarkUp. With an eye toward advances in the field, Bartman realized the City of Los Angeles was using MarkUp to collect feedback on documents for the Re:CodeLA project. Built by Urban Insight, Re:CodeLA's web design consultant and the planners and programmers behind Planetizen.org, MarkUp was not designed and deployed to be a stand-alone product. OSPCD persuaded Urban Insight to launch OpenComment – a rebranding of MarkUp – with Somerville and Somerville by Design as its first customer and early adopter [29].

Staff emphasized the heightened accountability that follows government forays into social media and open technology. Previously, for instance, remarks made at a conference out of town largely lived and died there. Today, OSPCD and the Mayor's office live-tweet highlights and engage in conversation via Twitter, with experts in the field as well as engaged Somerville residents who use the forum to hold staff members to a new level of accountability [30]. Remarks are picked up and monitored, raising the level of dialogue and breaking down barriers between the community and City Hall. At community meetings, residents expect staff to be up to the minute with information from Open Comment, to access all relevant documents in real time, and for any hard paper designs or surveys to be quickly uploaded for public access. Constituents can live-stream community meetings online, review public documents with ISSUU, participate in open conversation with MindMixer, and submit feedback via Open Comment. However, as Senior Planner Melissa Woods noted, on any given issue, people regularly join the conversation mid-process, explaining they were unaware of the ongoing dialogue.

12.2.2.3 Smart Cities and Planning in Somerville

At present, Somerville is undergoing several future-oriented planning processes, investing in smart governance to sow the seeds of a resilient and sustainable city. From neighborhood, open space, and transit plans, Somerville residents are actively involved in envisioning their future, using technology through the planning process and planning for future technology.

For several years, the City has partnered with Gehl Architects, a firm founded by legendary urbanist Jan Gehl, to foster a human-scale approach to urban life. Curtatone has embraced Gehl, an urban designer known for systematically measuring human behavior in cities, celebrating local research that “has shown that small changes in the build environment can make a huge difference” [31]. Gehl Architects have been studying humans and their use of cities for decades. Most cities have no idea how their parks, plazas, or sidewalks are used. They know more about the flow of automobile traffic at any given intersection than they do about the humans that live, work, or visit those same streets. Somerville has begun to integrate Gehl's systematic method for documenting the use of public space throughout the city in order to establish a baseline for ongoing improvements to the public life of the city.

This process starts by collecting data and by counting people – watching where they walk, what they are doing, and observing how the space functions. These metrics can verify certain assumptions about how the space is functioning and can provide guidance about what improvements can be made to encourage a more vibrancy to unfold. Continued measurement and verification of these human activities will be used to support the ongoing implementation of a larger vision for the area. Somerville has begun to measure what matters.

This focus on the human scale has been made possible through the SBD process. Fine-grained improvements will lead to more walkability, greater reliance on biking as a mode of transit, and great enjoyment of the public realm. These improvements can now be identified and systematically tracked, evidencing short-term gains that may be worth long-term investments in permanent infrastructure. This approach has allowed Somerville, a small city with limited resources, to achieve improvement in public life without the substantial investments often required to upgrade the public infrastructure that has such direct control over the vibrancy of the city's streets and squares.

Observed to be pursuing “an innovation economy agenda,” Somerville is employing smart governance and utilizing technology to foster nimble growth [32]. While the Mayor has been pitched on smart cities by IBM, Cisco, Verizon, and a swath of start-ups touting, for example, street lights as cell towers that transmit data and generate municipal revenue, Somerville is “not looking for a global, all encompassing platform” [23]. Wary of both committing to a single technology and burdening constituents with an early adopter tax, the city is discerning in its commitments. The city, in partnership with Code for America, is taking small steps – adding GPS to plows and writing smart technology into union contracts – and bigger steps, partnering with Audi to test self-driving car technology [23]. The partnership with Audi allows Somerville another avenue to explore how to get more out of the city's existing streets. This objective is shared across issue areas; the basic question is, how can the city build on its existing assets, and how can technology facilitate this capitalization? At the same time, Somerville is advocating for innovative technology and services to be brought to scale for small cities [23].

Somerville is moving into a new phase of open data and data management, trying to carve a path that continues to empower staff and residents alike. Many cities launch highly celebrated open data initiatives without a smart governance strategy behind them. Somerville did just the opposite, beginning with SomerSTAT, the city is moving from a well-managed community process to now enlivening its open data platform [30].

While the city has an existing open data portal, the majority is 311 data that is housed by constituent services and static [20]. At present, they are undertaking back-end work to incorporate data from the Assessors, Inspectional Services, Public Safety, and so on. They are moving toward a data dashboard and focused on owning their own data in vendor contracts. They seek out firms that respect that objective, clearly stating the “new expectation that our data is our data all the time” [23]. Moving forward, the Mayor's office aims to develop an application programming interface and transparent code that constituents can tweak [20, 29].

As cities look for ways to become more resilient, officials would be wise to embrace proactive community-led planning and the technology that enables it. The direct public involvement ongoing in Somerville informs City Hall of future opportunities for growth. As Brad Rawson, co-lead on SomerVision and now the Director of Transportation and Infrastructure for Somerville, emphasized, “Community led planning can lead to fiscal stewardship” [25]. Community members guide the plans for improving their neighborhoods; their commitment evidencing a level of community attachment any Somerville resident can attest to [6]. Temporary installations and other Tactical Urbanism approaches test the concepts developed through community-led planning, resulting in a more collaborative public process.

As Somerville hones its approach to community-led planning, the city is increasingly focused on the neighborhood level. This hyperlocal method has resulted in authentic plans for each neighborhood that, when combined, create a richer and more vibrant picture of the city than possible without such a high level of public dialogue. The city is simultaneously committed to integrating the latest technologies into the planning process and planning to ensure that Somerville benefits from smart technology at the appropriate scale.

12.3 Looking Ahead

12.3.1 Lessons from Somerville

Somerville is looking ahead to SomerVision 2.0 – a strategic plan that will be developed through robust community process. Curtatone aspires to guide the city toward the Net Zero and Vision Zero goals while receiving a AAA bond rating. This is the sustainable and resilient future of Somerville. The various goals Curtatone is championing can go hand in hand, but at present there is no organizational policy or strategy in place to ensure that they are aligned. The Mayor's dual commitments to managing for results and for transparency through community process have raised the level of engagement and constituent expectations. To get there, the city will have to further blur the lines across departments, moving beyond OSPCD to build a truly multidisciplinary plan.

Moving forward, City Hall will benefit from a more coordinated approach to technological engagement, especially through social media. At present, the various websites and listservs, while aiming to reach the maximum number of people possible, also ensure that communication is fragmented. Increasing virtual access to public meetings will invite greater participation. Moreover, the use of social media is largely limited to an English language audience. The city's hardworking SomerViva team of language liaisons is working to address these issues. With a new official Somerville City Hall website to be rolled out in 2016, there is potential for more intradepartmental alignment. A mapping feature, for example, will allow community members to self-select their neighborhood and opt-in to hyperlocal notifications.

Constituents routinely asked, “How did you get that number?” While they are eager to have the data readily available, some aspire to a data platform that allows constituents to answer that question themselves. To do so, OSPCD must continue to “STAT the plan” – working in tandem with the SomerSTAT team – and partnering with the community to build capacity. The level of research and analysis possible will grow exponentially once data sets are active on the city's dashboard. The potential for innovation will increase as community members can explore and engage with community assets in a whole new way. It may be possible to set outcomes-based metrics through an open and collaborative process in which community members can see both variables and results.

There is an understandable hesitancy in the public sector's commitment to quantitative targets, to pin down numbers that voters can reference time and again. OSPCD understood that few of their constituents would familiarize themselves with the full plan document; they wanted “headlines” to bring more people into the planning process, with full acceptance of the accountability that follows. Today, more than 5 years after the plan was published, the principle targets have “congealed in people's minds” [25]. The targets in SomerVision have helped build the community's planning skills, but few understand them to be iterative goals. OSPCD is aware that traditional plans are static documents and that “the day a plan is exported from InDesign it is already out of date” [29]. Staff are looking for ways to make plans “living documents”, using technology not just to improve access and dialogue but to make planning ever more iterative [29].

By advancing a culture of planning through technology, the legacy of one set of numbers loses its hold as the pace of discussion quickens and language becomes more ephemeral. Curtatone has an ambitious agenda and sees technology as a tool for the curious, posting that his interest in technology is really a quest of the curious that “technology enables curiosity (in the) pursuit of new ideas, to foster ingenuity and innovation” [32]. In his efforts to remake government in the image of a social enterprise, Curtatone encourages people to aim high and then figure out how to reach the stated goal.

Data can smooth the path, allowing for a more informed discourse when filtered through the tacit lens of the community. When the city needs to prioritize the allocation of resources, determining, for instance, how to ensure they are addressing deficiencies in the sewer system, planning for capital projects and greater resiliency, sensors can provide information on weak points in the infrastructure. This hyperlocal information can support a decision to fund repairs in one neighborhood over another, encourage residential storm water management through appropriate plantings, and even win the expansion of existing urban farms and gardens.

Cities flourish where there is a vibrancy to the life humming within, where technology “honors and leverages community assets” rather than molding them [25]. Somerville must continue to foster the authentic places that have instilled such a strong sense of community connection and employ technology to achieve a human-scale, sustainable, and resilient city. Doing so will require systems thinking, drawing on the economy of cities, to maximize the potential as a transit hub and center for innovation. Smart governance will enable smart cities to be in command of their own fate [25].

12.3.2 Recommendations

For cities looking to embrace the technology behind smart cities, smart governance will be critical to successful implementation. Somerville offers a strong case study for a small city, grappling with increasing demands on City Hall under resource-constrained conditions. For those looking to learn from the Somerville experience, the following can pave the way:

- 1. Plan for the future, the future is now

Planning for urban growth and health must be an ongoing process. Trading the conventional linear process for one that allows sequential planning efforts to overlap with previous ones is essential.

- 2. Respect authenticity in placemaking

Cities are in competition with one another. To foster community connectedness, smart governance must protect and advance authentic places.

- 3. View cities as dynamic, polycentric systems

The complex web of human life and activity that occurs in cities is what makes them the center for innovation. Smart cities must honor the parts that make the whole.

- 4. Invite data into all corners of City Hall

Quantitative analysis must be seen as a carrot to achieve results otherwise unimaginable and increase transparency not a stick brought down by management to expose deficiencies.

- 5. Craft community-led planning processes

Fostering a culture of iterative planning elevates the process with local insight and ensures community buy in.

- 6. Employ technology to advance engagement

Low-cost technology, when well coordinated, can expand outreach, increase the diversity of perspective by eliminating traditional barriers to participation, invite talent beyond City Hall, and gain trust.

- 7. Facilitate multidisciplinary teams

Smart cities face wicked challenges that belie traditional government departments. Collaboration is essential to efficiency and success.

- 8. Work at the neighborhood scale

Neighborhoods are dissimilar. A one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate; when appropriately applied, technology can illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of each neighborhood, and local insight can interpret the information to improve upon existing assets and shore up necessary deficiencies.

- 9. Aim high

Setting goals and inviting those within and around City Hall with data to determine those goals are empowering and need not be constraining.

- 10. Focus on resiliency and sustainability

From fiscal health and public health to educational and environmental policy, smart cities of the future will be increasingly resilient and sustainable (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Recommendations table

| Recommendation | Rational | Action |

| Plan for the future, the future is now | Planning for urban growth and health must be an ongoing process | Trade the conventional linear process for one that allows sequential planning efforts to overlap with previous ones is essential |

| Respect authenticity in placemaking | Cities are in competition with one another; authenticity fosters community and cannot be replicated | Protect and advance authentic places |

| View cities as dynamic, polycentric systems | The complex web of human life and activity that occurs in cities is what makes them centers for innovation | Honor individual parts of the city while taking a holistic approach |

| Invite data into all corners of City Hall | Quantitative analysis can achieve results otherwise unimaginable and increase transparency | Use data as a carrot, not a stick |

| Craft community-led planning processes | Local leadership elevates the process and ensure community buy in | Foster a culture of interactive planning with local insight |

| Employ technology to advance engagement | Low-cost technology, when well coordinated, can expand outreach, increase the diversity of perspective by eliminating traditional barriers to participation, invite talent beyond City Hall, and gain trust | Integrate technology with low barriers to entry into public sector projects |

| Facilitate multidisciplinary teams | Smart cities face wicked challenges that belie traditional government departments | Collaborate for the sake of efficiency and to achieve more successful outcomes |

| Work at the neighborhood scale | Neighborhoods are dissimilar. A one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate | Use technology to illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of each neighborhood and local insight to interpret the information to improve upon existing assets and shore up necessary deficiencies |

| Aim high | Ambition and inclusion are empowering | Set goals and invite those within and around City Hall with data to determine those goals |

| Focus on resiliency and sustainability | From fiscal health and public health to educational and environmental policy, smart cities of the future will be increasingly resilient and sustainable | Apply a resiliency and sustainability lens to every project and make them foundational |

Final Thoughts

Somerville, Massachusetts, exemplifies the possibility of municipal leadership and urban innovation. The case study illuminates how smart governance enables best practices in community-led planning and design. Smart cites can integrate these principles with emerging technologies to become more resilient and sustainable.

Questions

-

1 How do you define smart governance?

-

2 What is an authentic place?

-

3 How can a city's comprehensive plan inform the creation of neighborhood plans?

-

4 Give an example of a community-led planning process that has informed how the city used data for decision making.

-

5 Give an example of how data can inform physical planning.

-

6 How can city government better organize their departments to be more responsive to the concerns of creating authentic places?

-

7 Name three technologies that can allow city government to get innovative at low cost.

-

8 How did Somerville overcome its resource limitations to create smart neighborhood plans?

References

- 1 NewAmerica (2014) Stephen Goldsmith and Susan Crawford at New America, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

- 2 CSIS. (2014). “Smart Governance: How public policy can keep pace with technological developments.” Retrieved from http://csis.org/event/smart-governance-how-public-policy-can-keep-pace-technological-developments (accessed December, 2015).

- 3 PPS. “What is Placemaking?” Retrieved December, 2015, 2015, from http://www.pps.org/reference/what_is_placemaking/.

- 4 Townsend, A.M. (2013) Smart Cities; Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for the New Utopia New York, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- 5 Mechling, J. (2002) Information Age Governance: Just the Start of Something Big? governance.com, in Democracy in the Information Age (eds E.C.N.J. Kamarck and S. Joseph), Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp. 141–160.

- 6 Goldsmith, S.C. and Susan, C. (2014) The Responsive City, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

- 7 Thornton, S. (2015). “The Smart Chicago Collaborative: A New Model for Civic Innovation” Retrieved December, 2010, 2015, from https://www.livingcities.org/blog/444-the-smart-chicago-collaborative-a-new-model-for-civic-innovation-in-cities.

- 8 Keane, T.M.J. (2006) The Model City, Boston Globe, Boston, MA, New York Times Company.

- 9 Schwarz, H. (2014) The Most Influential Cities in the Country, According to Mayors, The Washington Post, District of Columbia The Washington Post Company.

- 10 NCL. (2015). “All-America City Award.” Retrieved December, 2015, 2015, from http://www.nationalcivicleague.org/previous-all-america-city-winners/.

- 11 Byrne, M. (2011) Somerville among 100 best places for young people, Boston, MA, New York Times Publishing Group, Boston Globe.

- 12 SHPC (2013) A Sampling of Industrial Somerville, Somerville, MA, Somerville Historic Preservation Commission and the Somerville Bike Committee.

- 13 Dungca, N. (2014) Somerville is top biking city around, Boston Globe, Boston, MA, The New York Times Company.

- 14 NWS. (2014). “Living in Somerville.” Retrieved December, 2015, 2015, from https://www.walkscore.com/MA/Somerville.

- 15 Goldsmith, S. (2009) Somerville's Joseph A. Curtatone. Management Insights, Governing.

- 16 Preer, R. (2005) Harvard Students Help Somerville Revamp Its Budgeting Process, CommonWealth.

- 17 COS(A) XXX. SomerSTAT. Retrieved from http://www.somervillema.gov/departments/somerstat (accessed December, 2015).

- 18 COS(B) XXX. “Mayor.” Retrieved December, 2015, 2015.

- 19 Proakis, G. (2015b) Personal Interview, Director of Planning. Somerville, MA

- 20 Stewart, S. (2015). Personal Interview, Director of SomerStat. Somerville, MA

- 21 COS(C). A Report on Wellbeing; The Happiness Project. Retrieved from http://www.somervillema.gov/departments/somerstat/report-on-well--being (accessed December 2015).

- 22 COS(D) (2015). ResiSTAT http://somervilleresistat.blogspot.com.

- 23 Hadley, D. (2015). Personal Interview, Chief of Staff Somerville, MA

- 24 APA-MA (2012). APA-MA is pleased to announce winners of the 2012 APA-MA Awards Program which honors outstanding planning projects and planning leadership.

- 25 Rawson, B. (2015) Personal Interview, Director of Transportation and Infrastructure. Somerville, MA.

- 26 OSPCD 2015. “Our Planning Methodology.” Somerville by Design Retrieved December, 2015, from http://www.somervillebydesign.com/about/.

- 27 Proakis, G. (2015a) Somerville by Design; Eight Strategies for Public Participation, Lessons from the SBD Charrettes, OSPCD, Somerville, MA.

- 28 Woods, M. (2015). Personal Interview, Senior Planner. Somerville, MA.

- 29 Bartman, D. (2015). Personal Interview, Senior Planner Somerville, MA

- 30 Staff, C. o. B. (2015) Personal Interview, City Staff. Somerville, MA.

- 31 COS(E) (2014). City, Congress for NEw Urbanism to Host Screening of “The Human Scale” at Somerville Theatre Jan. 30. Somerville, MA, City of Somerville

- 32 MIT (2014) Enterprise Forum Cambridge, in A Tech-Friendly Mayor (ed. R. Cronk), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.