Chapter 1

Backlash

In 2004 I read an article written jointly by Jim Nail, at the time a principal analyst at Forrester Research, and Pete Blackshaw, then chief marketing officer for Intelliseek. They quantified and defined the extent to which a sample set of trend-indicating online consumers were “pushing back” against traditional media. This was a turning point for me. I was working at GSD&M Idea City, an ad agency in Austin, Texas, where I was helping develop the online and integrated marketing strategy team. This was around the time when the first social networks began to gain critical mass. This caught my attention and became the focus of my work.

In this opening chapter, I’ll cover the origin of the social web and the events that ushered in the collaborative tools that consumers use as they make daily use of the information available to them on the social web.

Chapter Contents

- The Early Social Networks

- The Pushback Begins

- The Backlash: Measured and Formalized

- The Main Points

My first involvement with online services was in 1986. I had just purchased a Leading Edge Model D (so that I could learn about the kinds of things one might do with a personal computer). I signed up as a member of Prodigy, launched a couple of years earlier by CBS, IBM, and Sears. The underlying premise of Prodigy was that advertisers—attracted by members—would play a key role in the business success of what was called the first “consumer online service.” On the typical Prodigy page, the lower one-third of the screen was devoted to ads. These ads—more or less untargeted by today’s standards—were nonetheless a significant advancement in the potential for a marketer to directly reach an individual. Although it hadn’t been put to use yet, that computer—unlike a TV—had a unique physical address. The opportunity for truly personal adverting took a step forward.

Prodigy and, in particular, its contemporaries CompuServe and America Online, were in many ways the forerunners of present social networks and targeted online advertising. The thinking was that not only was reaching a large number of individuals potentially more valuable than reaching a mass audience, but that through technology, marketers just might be able to actually do something with these individual connections.

Individual, person-to-person connections have always been highly valued. The real-world community status of highly localized professionals—think of doctors, religious leaders, and insurance agents—comes from the fact that they are personally acquainted with each of the individuals who make up their overall customer base. This gives them the advantage of a highly personalized level of service. Assuming the service itself is acceptable (and if it’s not, they are quickly out of business), this personal bond translates directly into loyalty, a top goal of most brand marketers. Rather than a failure to recognize the value of one-to-one efforts—no rocket science there—it was a logistical challenge that thwarted marketwide adoption of highly localized, personal advertising. Simply put, a mechanism to efficiently reach individuals on a large scale didn’t exist. In the early nineties, that changed.

Although it had been in development for a number of years, the Internet as it is now known began its climb when the National Science Foundation (NSF) and its forward-thinking National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET) program laid the ground rules for it. It was the NSF that championed the cause of an “open” Internet—a network that any entity, including a business, could use for any purpose, including commerce. Combined with the proliferation of low-cost personal computers and the savvy foresight of the bulletin board operators, the opening up of the Internet put in place what is taken for granted now. Today, the “Global Village,” a term coined by Wyndham Lewis in 1948 and popularized by Marshall McLuhan in 1964 in his seminal work Understanding Media, is alive and well. The Global Village is understood in both a historical and a contemporary context through a partial excerpt from Wikipedia: The social and personal interactive norms preceding the 1960s are “being replaced …by what McLuhan calls ‘electronic interdependence,’ an era when electronic media replace[s] visual culture, producing cognitive shifts and new social organizations.” That certainly sounds familiar now.

The release of Prodigy and the significance of the potential of its integrated ad platform in targeting individuals are best understood in the context of the prevailing advertising media of the time, and in particular television. Under the leadership and vision of NBC executive Pat Weaver, TV had shifted in the 1950s from a locally controlled, single-advertiser-per-show model to a network-controlled, multi-advertiser (aka “magazine”) model. While this was great for the networks, marketers, and ad agencies—reaching national-scale audiences was good for business because it provided operational and marketing efficiency—it also meant that viewers were treated more and more like a mass audience. With only four networks in place—CBS, NBC, ABC, and for a bonus point (see sidebar), name the fourth—mass advertising was clearly the wave of the future. To be fair, media planning and placement meant that Geritol was directed primarily toward an audience with an older skew or component. As a young kid, however, I saw plenty of Geritol ads while I watched Ed Sullivan and wondered how a person could ever need “more energy.” Fifty years later, I know the answer: I now get my daily wings from Red Bull. Beyond big buckets such as “older” or “female,” the targeting capability we now take for granted wasn’t really possible. While some degree of targeting was achievable on early radio or locally controlled TV prior to the rise of the national networks, the ability to target a message to an individual was severely limited.

Bonus Point:

Figure 1-1: The New York headquarters of the fourth network

Name the fourth TV network active in the 1940s and ’50s. Hint: It’s not Fox, and I’ve given you a clue in Figure 1-1.

150 East 34th Street, New York. (Scott Murphy — http://members.aol.com/smurphy110/mid/515madsn.htm)

The fourth network, known for shows like Faraway Hill, Rhythm Rodeo, and Chicagoland Mystery Players, was the DuMont Television Network.

During the early years of television, ads made up less than 10 minutes of each one-hour show. The time devoted to commercials has more than doubled since then, with many half-hour shows now showing about equal amounts of program content and advertising. With this much time being devoted to what has become “content” in its own right—look no further than the Super Bowl ads for proof of the notion that ads are a distinct form of entertainment—it’s not surprising that a “pushback” began. The pushback was driven in a large part by the confluence of two major factors: the rise of the Baby Boomers and the arrival of the Internet-connected personal computer.

Spurred on by Boomer spending on electronics and the proliferation of the personal computer, by the mid-nineties the number of Internet websites had climbed from the 6,000 or so of 1992 to more than 1 million—and that was just the beginning. Email—still considered to be one of the earliest “killer apps”—had taken off as well. A developing world it was, too: While it seems incredible, into the mid-nineties email servers around the world sat open and unprotected, an oversight that would prove pivotal in the advent of the social web. Back then, if you knew the IP address or name of the server, you could use it to send mail, no questions asked. We’re talking about mail that recipients would actually get and read. Commercial mail hadn’t really happened yet. However, the combination of the NSFNET lifting the ban on using the Internet for commercial purposes and the relatively unprotected nature of mail servers made what happened next inevitable. The big question of when—and not if—this new medium would be used for advertising and whether or not this would be accepted on a large scale was on more than a few people’s minds. It was a question just waiting to be answered.

Hotel Exercise

Don’t try this at home. Instead, try it in a hotel room. When you’re in an unfamiliar city—and when all you have is a relatively crude remote control—try channel surfing to find out what’s on television. Unless you have a favorite channel and can jump right to it, the odds are higher that you’ll find a commercial rather than program content. The ads can be so thick you’ll find yourself surfing commercials. Don’t believe it? Try it.

A Big Boost from an Unlikely Source

On April 12, 1994, husband and wife Laurence Canter and Martha Siegel unknowingly gave social media—still more than 10 years in the future—a big boost when they provided an answer to the question of whether or not email could be used for advertising: It could. The “Green Card” spam that they launched is generally considered the first unsolicited email advertisement sent over the Internet. The result was explosive, on both sides. Enterprising minds quickly realized there was money to be made—lots of money—and relatively little actual regulation that could be applied to constrain them. The term spammer—loosely based, unfairly, on Hormel’s canned meat—was coined to describe people sending email filled with questionable content. But if you could stand the heat coming from those who made it their business to thwart this newfound advertising technique, you could get rich. Real rich. Real fast.

Just as quickly, recipients and their Internet service providers (ISPs) realized that this practice—novel as it was—was fundamentally objectionable, so they went to work on countermeasures. Cancelbot—the first antispam tool developed to automatically cancel the online accounts of suspected spammers—launched an entire movement of antispam tools. In 1997, author and Austin resident Tracy LaQuey Parker filed and won one of the first successful antispam lawsuits. (In case you’d like to read the judicial opinion, I’ve included a reference to it in the appendix of this book.) A domain she owned—Flowers.com—was used by Craig Nowak (aka C.N. Enterprises) to launch a spam campaign falsely identified as originating from Flowers.com and Austin ISP Zilker Internet Park. Oops.

Why Does This Matter?

The arrival of spam—on a communications channel that recipients had control over—shattered a peaceful coexistence that had been in place for 30 years. Viewers had accepted interruptions more or less without complaint as the quid pro quo for free TV (and amazingly, albeit to a lesser extent, on for-pay cable as well). Even if they objected, short of changing channels there was little they could do. Ads were part of the deal. The Internet—and in particular an email inbox—was different. First, it was “my” inbox, and “I” presumed the “right” to decide what landed in it, not least of all because I was paying for it! Second, spam—unlike TV ads—could actually clog my inbox, slow down the Net, and generally degrade “my” experience. People took offense to that, on a collective scale. Spam had awakened a giant, and that giant has been pushing back on intrusive ads ever since. On the social web, interruptions do not result in a sustainable conversation. In their purest form, all conversations are participative and engaged in by choice. This simple premise goes a long way in explaining why interruption and deception on the social web are so violently rejected.

The relevance of these particular events and those that have followed in driving the evolution of social media cannot be overstated. In one sense, the issues raised by spam—the practice of sending a highly interruptive, often untargeted message to a recipient—triggered a discussion about how advertising in an electronic age could, and more importantly should, work. At the same time, in the early days the messages weren’t as bad, the emails not as junky, and the content not so predatory. In the early days, it was about an annoyance for techies and a perceived (and misunderstood) opportunity for marketers. The questions were as much about how to make money as they were anything else, and not enough forethought was given to the recipient experience. Regardless, these discussions gave rise to the idea that recipients should have control over what was sent their way. The fact that their personal attention was worth money—something that ad execs had long known—was suddenly central in the discussions of the thought leaders who pushed all the harder against those who abused the emerging channels.

The offensive nature of spam, in particular, inflicted collateral damage on the ad industry as a whole. Ironically, and much to its own loss, the ad industry did little to stop it. Unsolicited email rallied people against advertising intrusion, and a lot of otherwise good work got caught in the crossfire. In contrast to TV ads, for example, spam fails to pay its own way, fails to entertain, and often contains deceptive messages. These are not the standards on which advertising was built. At GSD&M Idea City, the agency where I spent many years, agency cofounder Tim McClure coined the “Uninvited Guest” credo, which basically holds that a commercial is an interruption. As such, it is the duty of the marketer and advertiser collectively to “repay” the viewer, for example, by creating a moment of laughter or compassion that genuinely entertains. It is this recognized obligation to repay that transforms the interruption into an invitation. This symbiotic relationship sat at the base of an ad system that had worked well, and with relatively few complaints, for 50-plus years. Beginning with Tide’s creation of soap operas and the Texas Star Theater in the ’40s up to the Mobil-sponsored Masterpiece Theater in the ’70s, viewers readily accepted that advertisers were paying the freight in exchange for attention to their products and services. Measurable goodwill accrued to sponsors simply by virtue of their having underwritten these programs.

No more. By violating the premise of the “Uninvited Guest,” spammers brought to the fore a second and much more powerful notion among consumers: Spammers raised awareness of the value of control over advertising at the recipient level. Spammers galvanized an entire audience (against them) and created a demand for control over advertising at a personal level. With TV, radio, magazines, and even direct mail (the United States Postal Service has long enforced the rights of marketers to use its services so long as they pay for them) there was no viable means through which a recipient could select or moderate—much less block—commercial messages short of turning off the device. With digital communications, control elements are now built in; they are an expected part of the fabric that links us. If advertisers and network executives are experiencing angst over contemporary consumer-led “ad avoidance,” they have, among others, Laurence Canter and Martha Siegel to thank. By introducing unsolicited messages into a medium over which recipients can and readily do take ownership and control, the actions of the earliest for-personal-gain commercial spammers created in consumers both the awareness of the need for action and the exercise of personal control over incoming advertising. Antispam tools ranging from simple blacklists to sophisticated spam filters are now the norm.

As spammers continued to proliferate, spam became not only a nuisance but a significant expense for systems owners and recipients alike. It was only a matter of time before legislation followed. In 2003 the CAN-SPAM Act was signed into law. This was significant in the sense that legislation had been enacted that in part had its roots in the issues of recipient control over incoming advertising. This further validated—and pushed into the mainstream—the idea that “I own my inbox.” From this point forward, it would be more difficult as a marketer to reach consumers using email without some form of permission or having passed through at least a rudimentary inbox spam filter.

It wasn’t just email that felt the impact of growing consumer awareness of the control that now existed over interruptive advertising. On the Web, a similar development was taking place. In 1994, HotWired ran what were among the first online ads. Created by Modem Media and partner Tangent Design for AT&T, these ads invited viewers to “click here.” O’Reilly’s Global Network Navigator was running similar ads on its network, and others would follow. That the HotWired ads ran less than two weeks after the initial-release version (0.9) of Netscape’s first browser made clear that advertising and the online activities of consumers were linked from the get-go. The first online ads were simple banners: They appeared on the web page being viewed, generally across the top. Page views could be measured. DoubleClick founder Kevin O’Connor took it a step further: DoubleClick made the business of advertising—online, anyway—quantitatively solid. With online advertising now seen as fundamentally measurable, marketers sat up and took notice. Online advertising quickly established itself as a medium to watch. One of the results of the increasing attention paid by marketers and advertisers to online media was an increased effort in creating ads that would “cut through the clutter” and get noticed. As if right out of The Hucksters, someone indeed figured out a way. It was called the pop-up.

Like an animated “open me first” gift tag, the pop-up is a cleverly designed ad format that opens up on top of the page being viewed. Variants open under the page or even after the page is closed. Here again, it’s useful to go back to TV, radio, and to an extent print. Certainly, in the case of the TV, when the show’s suspense is built to a peak only to cut away to a commercial, that is a supreme interruption. But it was tolerated and even desired. The interruption provided a way to freeze and “stretch out” the moments of suspense. The pop-up is different. It’s not about suspense or entertainment. It’s about obnoxious interruptive behavior that demands attention right now.

So, it wasn’t long before the first pop-up blocker was developed and made available. Its development points out the great thing about open technology, and one of the hallmarks of the social web: Open digital technology empowers both sides. As brands like Orbitz made heavy use of pop-ups, others went to work just as hard on countermeasures (described in Brian Morrissey’s article “Popular Pop-Ups?” at www.clickz.com/showPage.html?page=1561411). Partly in response to marketers such as X10 and Orbitz, in 2002 EarthLink became the first ISP to provide a pop-up blocker free to its members. Again, the notion that an ad recipient had the right to control an incoming message was advanced, and again it was embraced. Pop-up blockers are now a standard add-on in most web browsers. The motivation for the social web and user-centric content control was going mainstream.

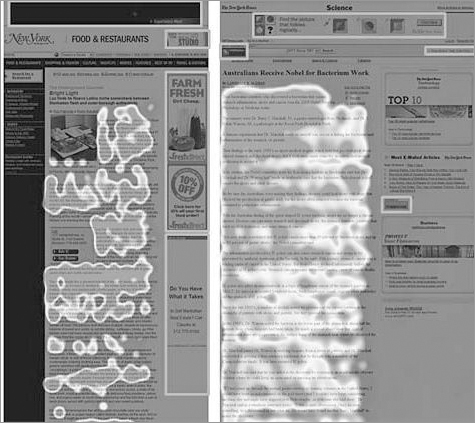

Heat Maps: Passive Ad Avoidance

Passive ad avoidance—the practice of sitting within view or earshot of an ad but effectively ignoring it—has been documented by Jakob Nielsen and others through visualizations such as the heat maps shown in Figure 1-2. Using eye movement–detection devices, maps of eye movement during page scans show that most consumers now know where to look … and where not to look. The advertisements in Figure 1-2 are the least-viewed areas on the page. Complete information on Jakob Nielsen’s “Banner Blindness” study may be found at www.useit.com/alertbox/banner-blindness.html.

Jakob Nielsen heat map showing ad avoidance, http://www.useit.com/alertbox/banner-blindness.html

Figure 1-2: The Heat Map and Passive Ad Avoidance

It was therefore only a matter of time before the combination of formal ad avoidance and content control would emerge in the mainstream offline channels. It happened in 1999, with the first shipments of ReplayTV and then TiVo digital video recorders, launched at the Consumer Electronics Show. From the start, the digital video recorder (DVR) concept was loved by viewers. To say it was controversial among advertisers, programmers, and network operators is putting it lightly. While initial penetration was low—just a few percent of all households had a DVR—in the first couple of years after launch, the impact and talk level around a device that could be used to skip commercials was huge. Most of the early DVRs had a 30-second skip-ahead button—a function now curiously missing from most. Thirty seconds is the standard length of a TV spot: This button might as well have been labeled “Skip Ad.” Combined with the fact that a DVR can be used to record shows for viewing later, the DVR was disruptive to TV programming. In one easy-to-use box, a DVR brings control over what is seen—unwanted or irrelevant commercials can be skipped as easily as boring segments of a show—and control over when it is seen.

Right behind the changes affecting TV were those aimed at the telephone. Long a bastion for among the most annoying of interruptive marketers—those who call during dinner—the telemarketing industry felt the impact of consumer control as the Do Not Call Implementation Act of 2003 substantially strengthened the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991. The Implementation Act established a list through which any consumer can register his or her phone number and thereby reduce the number of incoming telemarketing calls. There are some exceptions (nonprofits, political candidates, and a handful of others are still allowed to call) and some misguided efforts at evasion (exploiting loopholes like pretending to be conducting a survey) but in general the combined acts have been viewed as a success. Well in excess of 70 percent of Americans have now registered on the Do Not Call Registry. In 2007, an additional act—the Do Not Call Improvement Act—was undertaken to remove the “five-year renewal” requirement for those who have registered. Sign up once, and you’re on the list forever unless you take yourself off it.

Note: Are you on the Do Not Call list? Here’s where to find out and to obtain information about the list: www.donotcall.gov.

The Backlash: Measured and Formalized

Think back to what has been covered so far. A set of basic points that connect past experiences with email, online media, and traditional media to the present state of the social web emerges:

- The genie is out of the bottle: Consumers and their thought-leading advocates recognize that they own their inbox, their attention, and by extension (rightly or wrongly) the Internet itself.

- Online, people are annoyed with spam and with pop-ups. Spillover happened, and advertising in general got caught in the fray.

- Offline, people are now looking around asking, “What other interruptive advertising bothers me?” The Do Not Call list was implemented as a result.

If you take these events together—antispam filters, pop-up blockers, DVRs, and the Do Not Call Registry—it’s pretty clear that consumers have taken control over the messages directed their way. The genie is indeed out of the bottle, and it isn’t going back in. At the same time, if you consider the number of beneficial product- or service-oriented conversations that occur on Facebook, Twitter, and elsewhere on the social web using content posted and shared through services ranging from YouTube to Digg, it’s also clear that consumers want information about the products and services that interest them. After all, no one wants to make a bad purchase. Consumers want to know what works, and they want to share great experiences right along with bad ones. More information is generally considered better, especially when the information originates with someone you know. Which brings us to trust….

The idea of trust is perhaps the point on which most of the objectionable ad practices share common ground—that is to say, they lack trust—and the central issue on which the acceptance of social media is being built. It’s all about trust. It’s as if the question that consumers are now asking is as follows:

If you have to interrupt or annoy me to get your ad across, how valuable can what you offer really be? If you think I’m dumb enough to fall for this, how can I trust you?

The link between consumer backlash and the rise of social media first occurred to me in 2004. Recall that I was reading a report from Forrester Research, written by Forrester Research Principal Analyst Jim Nail and Intelliseek Chief Marketing Officer Pete Blackshaw. The Executive Summary of the report is as follows:

Consumers feel overwhelmed by intrusive, irrelevant ads. The result: a backlash against advertising—manifesting itself in the growing popularity of do-not-call lists, spam filters, online ad blockers, and ad skipping on digital video recorders (DVRs). Marketing campaigns of the future must facilitate consumers’ cross-channel search for information, going beyond the brand promises made in traditional advertising.

The report further detailed some fundamental insights, all the more impactful given that the source of the data was a joint report done by Forrester Research and Intelliseek, now part of Nielsen. The audience was a very good cross-section of “savvy online users”—about two-thirds female, with an average household income just more than $50K, 60 percent using broadband, and about 80 percent having five-plus years of experience online. This audience was not a snapshot of what was then mainstream, but rather a highly probable indicator of “what’s next,” of what mainstream would become: overwhelmed, with the result being a backlash.

Working in the ad industry at the time, as I read this report I thought, “Wow. This is simultaneously describing what I do as a professional marketer and how I feel as an ordinary consumer.” Being a “glass-half-full” kind of guy, I saw in Jim’s and Pete’s work two distinct opportunities:

- The opportunity to develop a formal marketing practice based on information that consumers would readily share with each other

- Quite selfishly, the opportunity to ensure better information for me to use when evaluating my own options as a consumer

Social media, and in particular its application in marketing and advertising, is at least part of my response to the first of these opportunities. Implemented well, the second follows from it. What social media is all about, and again especially as applied to marketing, is the smart use of the natural conversational channels that develop between individuals.

These conversations may take a positive or negative path—something I’ll spend a lot of time on in Chapter 6, “ Week 3: Touchpoint Analysis,” and Chapter 7, “Week 4: Influence and Measurement.” Either way, they are happening independently of the actions or efforts of advertisers, with the understanding that just as a marketer can “encourage” these conversations by providing an exceptionally good (or bad!) experience, so too can an advertiser “seed” the conversations by creating exceptional, talk-worthy events. Around these events awareness is created, and a conversation may then flow. Word-of-mouth marketing, like social media, operates in exactly this way. Social media and word of mouth are fundamentally related in that both rely on the consumer to initiate and sustain the conversation.

Advertisers can of course play a role in this: Advertisers can create images, events, happenings, and similar that encourage consumers—and especially potential customers—to talk or otherwise interact with current customers. Social media and word of mouth are also related by the fact that both are controlled by the individual and not by the advertiser or PR agency. This has a deep impact on the link between operations and marketing, a discussion I will take up in Chapter 5, “Week 2: The Social Feedback Cycle.” This theme will recur throughout the balance of Part II of this book.

When you consider the issues that face traditional marketers, and in effect create the motivation for considering complementary methods such as the use of social media in marketing, it’s not surprising that many of them are rooted in the core issues of trust, quality of life, value, and similar undeniable aspirations. The issue of trust can be understood best in terms of the word-of-mouth (including “digital word-of-mouth”) attributes related to trust. Word of mouth is consistently ranked among the most trusted forms of information. As a component of social media, trust seems likely to follow in the word-of-mouth-based exchanges that occur in the context of social media. In fact, it does.

In addition to trust, from an advertiser’s perspective, the primary challenges are generally clutter and fragmentation. The sheer numbers of messages combined with a short attention span (developed at least in part by watching stories with a beginning, middle, and end that together last for exactly 30 seconds) are challenges as well. In Branding for Dummies (Wiley, 2006), a claim is made that consumers receive approximately 3,000 messages per day. Other citations place that figure in the range of a few hundred to well in excess of a few thousand (one set of estimates is available at http://answers.google.com/answers/threadview?id=56750). Even at the low end of the scale, several hundred messages each and every day mean that as humans we have to be actively filtering. That in turn requires some sort of associative decision-making process. In the preface of this book, I made the case that we are social beings and that we have adopted what would be loosely called “social behaviors” because we believe them beneficial. Our ability to deal with incoming information in anything like the volumes estimated makes apparent the need for collaboration in problem solving. Through social media—enabled by the Internet and the emergence of the social web—we are beginning to embrace the tools that significantly extend our collaborative abilities. These tools, taken as a whole, are the new tools of the social marketer.

Chapter 1 has introduced the basic motivation for consumers’ adoption of the social web, and at least partially explained the use of social media to arrive at more informed purchase decisions. Chapter 1 covered the following:

- The increasing influence of the consumer via social content and the diminishing role of the marketer and the primary advertising message

- The cause of the backlash that developed when the practice of pushing ads to consumers moved to the digital platform, a platform over which consumers (end users) actually have control

- The role of trust as a central component in marketing effectiveness in contemporary social conversations