Chapter 12. The Filesharing Networks

Criminal: A person with predatory instincts who has not sufficient capital to form a corporation.

It all began in 1999, when an 18-year-old college dropout named Shawn Fanning got fed up with trying to find and download music files off the Internet. So he wrote a program that could search for and share music files and exchange instant messages with other people on the Internet. When Fanning released his creation, called Napster, little did he know that he would wind up changing the world.

Note

For more information about filesharing, pick up a copy of Steal This File Sharing Book, published by No Starch Press.

A Short History of Internet FileSharing

Fanning didn’t invent Internet filesharing with Napster, but he definitely made it more convenient. Of course, people have been sharing recorded information for years. Software pirates copied floppy disks, and later CDs, and traded them with each other (see Chapter 6 for more information about software piracy), and music lovers recorded and swapped tape cassettes of their favorite albums, long before Internet filesharing existed.

People have been sharing files over the Internet through websites, FTP sites, and Usenet newsgroups for as long as such technology has existed. Although these vehicles made sharing files easy, searching for files was difficult.

You could use a search engine such as Google to find specific files on different websites, but you’ll wind up sifting through lots of irrelevant links. Or you could use a special FTP search engine to find certain types of files stored on FTP servers around the world, but you’d have to repeat the search for each file and visit and search each FTP site separately.

Usenet newsgroups are great for sharing files anonymously (because nobody knows who posted any file), but they aren’t searchable; people just have to take whatever happens to be available at the time.

The beauty of Napster was that it combined the abilities to search for files and to download files conveniently within a single program. Although originally designed to share only music files, typically those stored in the MP3 file format, Napster defined the basic filesharing model: create a network of computers that can search for and share files with every other computer on that same network.

How FileSharing Works

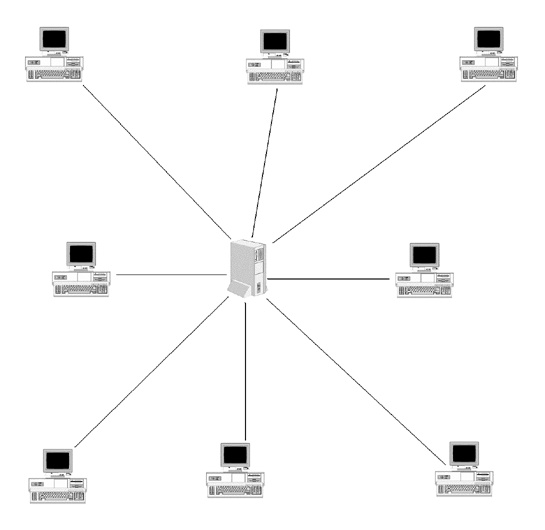

At the simplest level, filesharing becomes possible whenever two or more computers connect to each other. To search for files on the original Napster, people connected directly to Napster’s server and submitted their requests, and then the server queried every other connected computer to determine which ones had the requested files, as shown in Figure 12-1.

Because all search requests went through that main server, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) managed to close Napster down by getting a court order that simply required Napster to shut down its servers. Without the servers, no search requests could take place and, hence, no filesharing could occur. As far as the RIAA was concerned, it had eliminated a rampant source of copyright infringement by stopping people from trading MP3 files of their favorite songs.

The birth of Gnutella

After studying the weaknesses of Napster’s centralized server network design, a programmer named Justin Frankel created a similar filesharing network dubbed Gnutella. Unlike Napster, search requests went through every computer connected to the network, not just the central server, as shown in Figure 12-2. As a result, a Gnutella network could never be shut down at a single choke point.

To publicize Gnutella’s existence, Justin posted the Gnutella source code on the website of a company called NullSoft on March 14, 2000, so that others could study his creation. Within hours, America Online (the owner of NullSoft) ordered the source code removed, but not before copies had managed to spread all over the Internet and a new filesharing network had been born.

Because of its decentralized nature, nobody really controls Gnutella, which means nobody can really shut it down either. Over time, many programs, called clients, have been written to allow users to tap into the Gnutella network. Although there are dozens of different Gnutella clients available, two of the more popular ones are BearShare (www.bearshare.com) and LimeWire (www.limewire.com), which is shown in Figure 12-3.

Warning

Many filesharing client programs may come loaded with adware/spyware. When in doubt, always look for a client that specifically advertises that it is adware- and spyware-free.

Since so many people have created clients to access the Gnutella network, it’s difficult to update and improve the Gnutella network without everyone’s cooperation. As a result, programmers have created a similar, but more advanced, version dubbed Gnutella2, or just G2 (www.gnutella2.com).

Although based on Gnutella, Gnutella2 is an entirely separate filesharing network designed to accelerate file searches. Despite the improvements, most Gnutella2 clients still connect to the older Gnutella network as well, allowing users to search for files on both networks simultaneously.

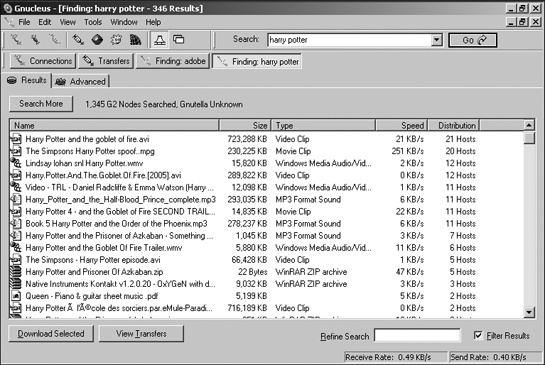

Two popular Gnutella and Gnutella2 clients are Gnucleus (www.gnucleus.com) and Shareaza (http://shareaza.sourceforge.net).

The Ares network

Dozens of client programs tap into the Gnutella network every day. Unfortunately, Gnutella’s popularity has also limited its growth. With no one effectively controlling it, the network cannot change or improve unless all Gnutella clients change and improve at the same time, which is nearly impossible.

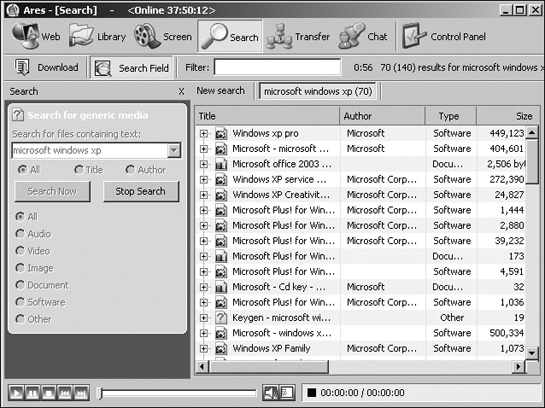

Moreover, even though Gnutella’s greatest strength is its decentralized network, that also causes file searching to take a long time, since each file request has to go through every computer connected to the network. Given these limitations, many former Gnutella clients have broken away and started their own filesharing networks. One of the first examples of these is called Ares (http://aresgalaxy.sourceforge.net).

The Ares filesharing network primarily carries MP3 music files, but you can find a variety of other types of files as well. Figure 12-4 shows some pirated copies of Microsoft Windows XP found on the Ares network, along with Windows XP cracks and key generators.

The FastTrack network

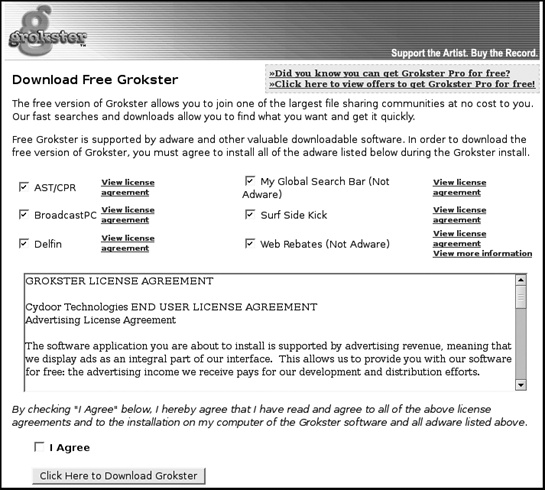

Perhaps the most infamous filesharing network of all is FastTrack, which can only be officially accessed using the Kazaa (www.kazaa.com) client developed by the same company. Unlike Gnutella, FastTrack is a closed, proprietary network that only licensed clients are allowed to access.

Like Gnutella, FastTrack is a decentralized network, but it offers three major advantages. First, FastTrack can download files from multiple sources to speed up file transfers and ensure that you get the file you want, even if one or more computers disconnect from the network. Second, FastTrack can resume downloading an interrupted file transfer so you don’t have to start all over again. Third, FastTrack can search for files quickly by dividing its network into sections, called nodes, where each node is linked to a computer designated as a Supernode.

Rather than search every computer on the network like Gnutella does, FastTrack searches only each Supernode; each Supernode searches its linked nodes for the requested file. This accelerates file searching so that, regardless of how many computers are connected to the network, file searching won’t slow down, as can happen on the Gnutella network.

The biggest drawback of the FastTrack network is that the free version of Kazaa comes loaded with adware/spyware. Figure 12-5 shows a typical agreement specifying all the different adware/spyware that may get installed on your computer when you install the Grokster filesharing client program, which once connected to the FastTrack network just like Kazaa.

If you don’t want adware/spyare installed on your computer but you still want to access the FastTrack network, you can either pay for the non–adware/spyware version of Kazaa, or you can use an unofficial FastTrack client called KLT K++ (www.klitetools.com). The owner of FastTrack, Sharman Networks, frowns upon any unofficial FastTrack clients, however, so they’re constantly changing the network to keep rogue client programs like KLT K++ from working. But then the programmers of KLT K++ rewrite their client program and reconnect to FastTrack once more, until the next time Sharman Networks changes FastTrack again.

To make connecting to the FastTrack network even simpler, grab a copy of Kazaa along with a copy of Diet K (www.dietk.com). Diet K will remove all the adware/spyware that Kazaa installed without sacrificing any of the benefits of the official client program.

Sharing Large Files

No matter how many filesharing networks pop up, they’re all based on the original Gnutella design of a decentralized network. The minor differences among the different networks mostly concern the searching and downloading of different files.

The filesharing networks already discussed were great for music files (typically MP3 files ranging in size from 3MB to 10MB), but they weren’t so great for sharing massive files of the contents of an entire CD or DVD, such popular programs as Adobe Photoshop, or an illegal video file copy of Star Wars. It simply took too long, as much as several hours, to share the contents of a CD (typically 650MB in size) or a DVD (typically 4.7GB in size).

For that reason, programmers soon came up with special filesharing networks dedicated to large files. The two most popular are eDonkey and BitTorrent.

With most filesharing networks, you can’t start sharing any files until you’ve finished downloading them from another computer. With both eDonkey (www.edonkey.com) and BitTorrent (www.bittorrent.com), you can start sharing files even while you’re receiving them, which means you can download and share a file simultaneously, making large file transfers faster and more reliable.

The Problem with Filesharing

From a technical point of view, there’s nothing wrong with filesharing. The creators and owners of many types of files want to distribute them freely as widely as possible. Many musicians release MP3 files of their songs, hoping to attract an audience. Aspiring radio broadcasters can store interviews as MP3 files and distribute them as sound files, known as podcasts, that anyone can download and listen to whenever they want. To find different podcasts, visit the Podcast Directory (www.podcast.net).

Amateur filmmakers may release their projects over filesharing networks to spread the word, and software publishers often release demos of their products via filesharing networks. Many Linux distributions actually depend on people using filesharing networks to spread them around the world.

So, from a technical standpoint, filesharing is great for people who want to distribute their own copyrighted material. The problem is that legal applications of filesharing are dwarfed by the widespread illegal ones.

Because both BitTorrent and eDonkey are optimized for sharing large files, you can often find the latest Hollywood movies being swapped on these networks, sometimes even before they’re officially released in theaters. BitTorrent and eDonkey are also favorite networks for swapping entire music albums and CDs or popular programs such as Microsoft Office or Adobe Illustrator.

If they just want individual songs from an album, most people flock to the older filesharing networks, such as Gnutella or FastTrack. There, they can copy the best songs off an album, store them as MP3 files, and then pass the files around. Their convenience and ease of use make the filesharing networks havens for rampant software, music, and video copyright violations, as shown in Figure 12-6.

The RIAA, the movie studios, and book publishers are trying to crack down on such blatant copyright infringement, but, with so many different filesharing networks available and nearly all controlled by nobody in particular, trying to shut down a filesharing network is nearly impossible. Tracking down individual violators is often too costly and time-consuming, except in extreme cases where individuals are sharing hundreds or thousands of movies or songs, or distributing the latest blockbuster movie or eagerly awaited pop album before it’s officially released.

Although the RIAA has had limited success suing blatant copyright violators, it’s having more success taking legal action against the companies that make the filesharing programs in the first place. In 2005, US courts shut down Grokster, one of the few licensed clients allowed to access the FastTrack network. That same year they also shut down WinMX, a filesharing program that originally tapped into the OpenNap network, but later evolved to form an independent filesharing network. The RIAA will likely continue to pursue legal action against any company that makes money selling filesharing programs. (This still leaves the free filesharing programs untouched.)

Like it or not, filesharing is here to stay. The real debate isn’t how to stop it but how to take advantage of it—legally. The RIAA and Hollywood movie studios claim that filesharing hurts their business. The producers of the 2004 bomb Soul Plane actually claimed that the movie did poorly at the box office because too many people had downloaded an advance copy off filesharing networks, rather than seeing it in theaters. For anyone who hasn’t seen Soul Plane, the quality of the movie can be summed up in one person’s comment on the Internet Movie Database site (www.imdb.com): “Glad I didn’t pay to see this movie.”

Even musicians are torn between the advantages and disadvantages of filesharing. Some claim that it hurts album sales, but others say it increases their potential audience and actually encourages people to buy their albums. The band Queen has even collected the best bootleg recordings of their old concerts and offers them for sale on their own website.

For more information about the latest filesharing networks popping up or getting shut down, visit ZeroPaid (www.zeropaid.com) or Slyck (www.slyck.com), shown in Figure 12-7.

Filesharing networks represent a new opportunity for some and a threat to others. Which side of the debate you take depends entirely on how you stand to profit (or lose) from the continuing growth of filesharing technology.