Chapter 13. The Internet Con Artists

Obviously crime pays, or there’d be no crime.

When most people think of Internet crime, they picture hackers stealing credit card numbers and racking up huge charges for somebody else to pay. Although this can and does occur, the biggest threat on the Internet isn’t hackers, it’s con artists, many of whom are no more competent at using a computer than the people they’re victimizing.

Whether con artists are fleecing a victim in person, through the mail, over the telephone, or over the Internet, all follow the same basic approach:

Promise a fantastic reward in return for little or no effort. (Victims are usually too blinded by their own greed to question why the con artist would want to help them in the first place.)

Exploit the victim’s trust. (Con artists encourage victims to demonstrate their trust in order to show they deserve the promised reward.)

Collect the victim’s money. (Con artists must trick a victim into giving up money or something equally valuable.)

Not surprisingly, con artists and politicians often use identical tactics. Politicians always promise that they’re serving the voters’ interests without revealing their own motives (Step 1). Then they appeal to the voters’ trust by implying that they’ll benefit if the particular politician is elected to office (Step 2). Finally, the politician appeals for the voters’ support (Step 3), which leads to power and money for the politician. In the case of usual politics, the money goes toward promoting the politician’s reelection and other political maneuvers. In the case of a crooked politician, the voters get conned and left with nothing.

Because nearly everyone would love to make a lot of money without doing any work, all of us are potential victims of con games. To avoid falling prey to an Internet scam, take some time to educate yourself on the different types of cons that have been duping people for years.

Charity Scams

Every time there’s a disaster anywhere in the world, con artists try to take advantage of people’s generosity. These charity scams often involve fake charity websites with legitimate-sounding names that accept online payments, such as transactions made through PayPal. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for example, website names that were not affiliated with any legitimate charities included www.katrinareliefonline.org, www.katrinahelp.com, and www.katrinadfamilies.com.

Phony charity websites can attract people who want to donate money, but con artists often go one step further and actively solicit donations through spam. Such unsolicited email will often mention the name of a fake charity that’s very similar to a legitimate one, such as the National Cancer Society (instead of the legitimate American Cancer Society) or the National Heart Institute (instead of the legitimate American Heart Institute).

These con artists can scam you in two ways. First, if you donate money, you’ll be giving your cash to a con artist instead of to a charity. Second, if you give the con artist your credit card number, you’ll risk having him run up huge charges.

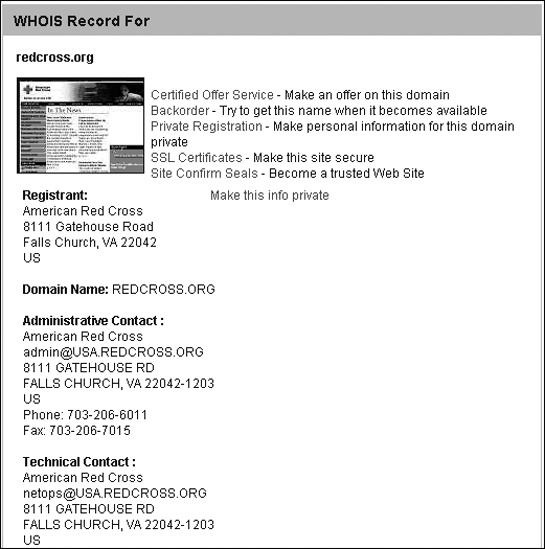

To avoid charity scams, never donate money to any organization that sends unsolicited email, and never provide your information to a telemarketer seeking donations over the phone. Because blanket telemarketing is expensive and time-consuming, few legitimate charities rely on it to raise money. A legitimate organization will provide a website or mailing address if you ask, and making this your standard procedure will ensure that you have the time and ability to investigate the charity. Before you make any donations, check out the charity’s name. Bogus websites often create logos that look similar to those of legitimate charities. A simple search using Google or on the Better Business Bureau website (www.bbb.com) will uncover well-known frauds. You can often tell a fake charity from a legitimate one by doing a WHOIS search (www.networksolutions.com/whois) on the domain name. If the WHOIS search reveals that the owner of the domain name is the charity you expected, such as the American Red Cross for the redcross.org domain name, as shown in Figure 13-1, then the website is most likely legitimate. If the WHOIS search reveals an individual or an organization other than the charity promoted by the website, you might want to investigate the charity more closely before sending any money.

Even legitimate charities themselves can fall prey to con artists. The former chief executive of the United Way once pled guilty to stealing $500,000 from the charity, channeling donations into his own pockets instead of toward the worthy causes they were meant to support. So even if you give to a legitimate charitable organization, it’s possible that your money will not help someone who actually needs it.

If you really want to help others, do the research to find a reputable charity. When you give to that charity, use the methods you’ve researched and verified (by clicking on a secure online link, sending your check to a mail address, or by calling a phone number). Better yet, donate your time by volunteering. That way you can be sure your money isn’t being wasted. For more on giving money to charities, visit the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance at www.give.org. To research and learn about different (valid) charities, visit Charity Search (www.charitynavigator.org). If you suspect that a charity could be fraudulent or dishonest, visit Google and search for the charity name along with words like scandal or scam to find information from people who might have been conned by that particular charity.

Even if you find a valid charity, be careful of their privacy policies. To earn additional income, some charities may sell your name, address, and email address to market research firms, which means you could donate money for a good cause and then wind up getting junk mail and spam in return for your effort.

The Area Code Scam

Some scams leverage the proliferation of newly created telephone area codes. The con artist starts by leaving a phone message or by sending an email claiming that you’ve won a fabulous prize in a contest, or that your credit card was incorrectly charged, or that one of your relatives is in trouble—anything to prompt you to return the call or respond to the email.

If you call the phone number provided in the message, you may be placed on hold, directed to a long-winded recorded message, or put in touch with someone who speaks broken English. In any event, the person on the other end simply tries to keep you on the phone as long as possible because (surprise!) the phone number is really a pay-per-call service (much like a 1-900 number) that charges you (the caller) astronomical rates, which can amount to as much as $25 per minute.

The area code most commonly used in this scam is 809, which is actually located in the Caribbean. Thus, the scammer can avoid American laws, such as those requiring that he warn you in advance of the charges being incurred and state the per-minute rate involved, or that there must be a provision for terminating the call within a certain time period without being charged. However, because no international code is required to reach the phone number, most people won’t even realize that they’re making an international call.

Area code scams are extremely hard to prosecute. The victim actually initiates the call, so neither the local phone company nor the long distance carrier is likely to be of any assistance or to cancel the charges.

To avoid this scam, be careful when returning unknown phone calls with unfamiliar area codes. As more people are learning about the 809 scam, con artists have switched to other area codes such as 242 (the Bahamas), 284 (British Virgin Islands), and 787 (Puerto Rico), as well as 500 and 700 prefixes, which are commonly used for pay-per-call adult entertainment services.

If in doubt, check an area code’s location first by visiting the LincMad website (www.lincmad.com).

The Nigerian Scam

Many people in other countries hate Americans, which isn’t surprising when you realize that many foreigners know the United States only through the actions of stereotypical “ugly” American tourists and American politicians (many of whom are disliked in their own country, too).

People in other countries get most of their information about Americans from American television shows. After watching shows like Sex and the City, lots of people in other countries believe that Americans are not only rich and beautiful, but lousy actors as well.

Regardless of the foreign perception of Americans, the fact remains that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries on the planet. Given the wide disparity between the average American’s income and that of people in other countries, for many people there’s not much guilt or shame in conning Americans out of their money at every available opportunity.

Not only have many scams originated in Nigeria, but the Nigerian government itself has been involved to the point that many believe that international scams are the country’s third largest industry. The general view in Nigeria is that if you can cheat an American out of his money, it’s the American’s fault for being gullible in the first place.

Nigerian scams are often called “Advance Fee Fraud,” “419 Fraud” (four-one-nine, after the relevant section of the Criminal Code of Nigeria), or “The Fax Scam.” The scam works as follows: The victim receives an unsolicited email message, fax, or letter from Nigeria containing a money-laundering proposal disguised as a seemingly legitimate business plan involving crude oil or as a notice about a bequest left in a will.

The fax or letter usually asks the victim to facilitate transfer of a large sum of money to the victim’s own bank and promises that he will receive a share if he pays an “advance fee,” “transfer tax,” “performance bond,” or government bribe of some sort. If the victim pays the fee, complications mysteriously arise that require the victim to send more money until he runs out of money, patience, or both.

With the growing popularity of the Internet, Nigerian con artists have been very busy. Don’t be surprised if you receive email from Nigeria asking for your help. The following is an example:

Dear Sir

I am working with the Federal Ministry of Health in Nigeria. It happens that five months ago my father who was the Chairman of the Task Force Committee created by the present Military Government to monitor the selling, distribution and revenue generation from crude oil sales before and after the gulf war crisis died in a motor accident on his way home from Lagos after attending a National conference. He was admitted in the hospital for eight (8) days before he finally died. While I was with him in the hospital, he disclosed all his confidential documents to me one of which is the business I want to introduce to you right now.

Before my father finally died in the hospital, he told me that he has $21.5M (twenty one million five hundred thousand U.S. Dollars) cash in a trunk box coded and deposited in a security company. He told me that the security company is not aware of its contents. That on producing a document which, he gave to me, that I will only pay for the demurrage after which the box will be released to me.

He further advised me that I should not collect the money without the assistance of a foreigner who will open a local account in favor of his company for onward transfer to his nominated overseas account where the money will be invested.

This is because as a civil servant I am not supposed to own such money. This will bring many questions in the bank if I go without a foreigner.

It is at this juncture that I decided to contact you for assistance but with the following conditions:

That this transaction is treated with Utmost confidence, cooperation and absolute secrecy which it demands.

That the money is being transferred to an account where the incidence of taxation would not take much toll.

That all financial matters for the success of this transfer will be tackled by both parties.

That a promissory letter signed and sealed by you stating the amount US $21.5M (twenty-one million five hundred thousand US Dollars) will be given to me by you on your account and that only 20% of the total money is for your assistance.

Please contact me on the above fax number for more details. Please quote (QS) in all your correspondence.

Yours faithfully,

DR. AN UZOAMAKA

To learn more about scams originating in Nigeria, visit the 419 Coalition website (http://home.rica.net/alphae/419coal). If you’re foolish enough to send money to the con artist running this scam, you’ll most likely receive a subsequent email saying that there were additional delays or problems, such as unforeseen fees, fines, or bribes that need to be paid. The goal is to keep you sending money for as long as possible. In some cases, people have sent thousands of dollars to these con artists while others have actually traveled to Nigeria to meet with the con artists in person. In 2003, a 72-year-old man in the Czech Republic lost his life savings to a Nigerian con artist and took his frustration out by shooting a Nigerian diplomat.

Since the United States sent troops to Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001, a new variation on the Nigerian scam has emerged. In this adaptation, potential victims receive an email supposedly from an American soldier who has discovered a large stash of money and needs help sneaking it back to the United States. Other than using the name of an American soldier instead of a Nigerian official, the scam is the same.

Similar to the Nigerian scam is the advance loan scam, which promises to loan you money at an extremely low interest rate. All you have to do is pay an advance fee for “processing.” Once the con artist receives your money, complications mysteriously occur. You never get the loan you expected, and the con artist walks away with your advance fee.

Work-at-Home Businesses

Another common scam often promoted in unsolicited email promises fabulous moneymaking opportunities that can be achieved at home with little effort. This type of scam is not new. Con artists originally perpetrated these scams using post office boxes and letters; today’s scam artists use the reach of the Internet and the simplicity of email to reach more potential victims faster than ever before. This should give you yet another reason to avoid receiving, let alone reading, any unsolicited email (see Chapter 18 for more information about spam). This section lists some typical examples of these scams.

Stuffing envelopes

The most common work-at-home business scam claims that you can earn hundreds or thousands of dollars stuffing envelopes in your spare time.

First of all, who in his right mind would want to spend his life stuffing envelopes? If this prospect actually appeals to you and you send money for more information, you need to seriously examine your aspirations in life. If you send money, you’ll probably receive the following:

A letter stating that, if you want to make money, you should just place your own ad in a magazine or newspaper offering to sell information to others about how they can make money by stuffing envelopes. There’s no envelope-stuffing involved at all.

Information about contacting mail-order companies and offering to stuff their envelopes for them. Unfortunately, you’ll soon find that stuffing envelopes pays less than Third World wages.

Make-it-yourself kits

Another work-at-home business scam offers to sell you a kit (such as a greeting card kit). You’re supposed to follow the kit’s instructions to make custom greeting cards, Christmas wreaths, flyers, or other products and then sell the products yourself as a quick way to start your own business. The business may sound legitimate, but the kit is usually worthless, and always overpriced, and the products that it claims you can sell will rarely earn you enough to recoup the cost of your original investment.

Work as an independent contractor

Rather than start your own business making products from do-it-yourself kits, why not work as an independent contractor for a company that will take care of the hassles of marketing and selling for you? This scam claims that a company is willing to pay thousands of dollars a month to have you help it build something, like toy dolls or baby shoes. All you have to do is manufacture these items at home and sell them to the company.

If you’re foolish enough to send money, you’ll receive instructions and materials to build whatever product you’re supposed to make. However, the materials are often cheap and easily obtainable for a fraction of the price at your local stores.

What usually happens is that the work is so boring that most people give up before they even get to the point of selling one batch of the product (often there is a high minimum purchase amount listed in the instructions). For those with greater perseverance, the company will often claim that the workmanship is of poor quality (whether it is or not) and thus refuse to pay you for your work. Either way, someone else now has your money.

Fraudulent sales

People have been fooled into buying shoddy or nonexistent products for years. The Internet just provides one more avenue for con artists to peddle their snake oil. Scammers can reach a mass audience by spamming thousands of email addresses every day. Two popular types of fraudulent sales involve “miracle” health products and investments.

Miracle health products have been around for centuries, claiming to cure everything from impotence and indigestion to AIDS and cancer. Of course, if you buy one of these products, your malady doesn’t get any better—and may actually get worse. In the meantime, you’re stuck with a worthless product that may consist of nothing more than corn syrup and food coloring.

Investment swindles are nothing new either. The typical stock swindler dangles the promise of large profits and low risk, but only if you act right away (so the con artist can get your money sooner and keep you from researching the “bait,” only to realize its true nature as a scam). Many stock swindlers visit investment forums or chat rooms, such as those on America Online, and scout these areas for people willing to believe their promises of “ground-floor” opportunities and to hand over money to complete strangers.

Like worthless miracle health products, investment scams may sell you stock certificates or bonds that have no real value whatsoever. Typically these investments focus on gold mines, oil wells, real estate, ostrich farms, or other exotic investments that seem exciting and interesting but prove to be nonexistent or worthless.

Pyramid Schemes

The idea behind a pyramid scheme is to get two or more people to give you money. In exchange, you give them nothing but the hope that they can get rich too—as long as they can convince two or more people to give them money, and so on. The most common incarnation of a pyramid scheme is a chain letter.

A typical chain letter lists five addresses and urges you to send money (one dollar or more) to each of them. It instructs you to copy the chain letter, removing the top name from the list of addresses and putting your own name and address at the bottom, and mail five copies of the chain letter to other people. The promise in the letter is that if you send the five dollars (or more), you can just sit back and wait for fabulous riches to come pouring into your mailbox within a few weeks—one dollar at a time. (Those who want to con others out of money probably realize that it’s faster to simply start a new chain letter with their name at the top.)

Many chain letters require you to sign a letter agreeing that you are offering the money as a gift or that you are buying the five addresses as a mailing list. In this way, the chain letter author says, you will not be breaking any laws.

Most people receive chain letters as unsolicited email, but a unique twist on the chain letter scam, called Mega$Nets, appeared in the early ’90s. Unlike a text-only chain letter, Mega$Nets was a computer program that let people type in their name and address using a specially generated code, which users could buy and then offer to sell to others.

Mega$Nets claimed that it wasn’t a chain letter because people were paying for its software (which was actually just an electronic version of a chain letter). Mega$Nets was spread by people posting copies on personal websites where others could download it and join this “incredible money-making opportunity.”

Multilevel marketing (MLM) business opportunities are similar to chain letters. Valid MLM businesses offer two ways to make money: by selling a product or by recruiting new distributors. Most people who get rich within an MLM business do so by recruiting new distributors. Unfortunately, many scams masquerade as legitimate MLM businesses with the key difference that you can make money only by recruiting others; the only product being sold is a nebulous “business opportunity.”

Pyramid schemes often make a few people very wealthy, but at the expense of nearly everyone else at the bottom of the pyramid. Nowadays, those running pyramid schemes can recruit new members through Usenet newsgroups or by spamming multiple email accounts (see Chapter 18). Once you realize that pyramid schemes need your money to make other people rich, you won’t be taken in by the offers that come your way, no matter how tempting.

The Ponzi scheme

Among the oldest and most common investment scams is a variation on the pyramid scheme known as the Ponzi scheme, named after post–World War I financier Charles Ponzi, who used money from new investors to pay off early investors. Because the early investors received tremendous returns on their investments, they quickly spread the news that Charles Ponzi was an investment genius. New investors rushed forward with wads of cash, hoping to get rich too, at which point Charles Ponzi took the money and ran.

Note

Social Security is basically a Ponzi scheme, because it pays current recipients out of current investors’ funds. This requires more people to pay into the system all the time, which explains why it’s perpetually in danger of going bankrupt.

Con artists are now running Ponzi schemes over the Internet through email, faxes, or websites offering “Incredible investment opportunities!” In 2006, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) accused the owners of 12dailypro.com of running an Internet Ponzi scheme that bilked “investors” out of more than $50 million. These would-be investors were allegedly promised a 44 percent return on their investments in 12 days. After purchasing “units” at $6 apiece, investors would get paid to look at advertisements on the Internet. The money supposedly came from the advertisers, but the SEC claims the money really came from other so-called investors.

Any time anyone promises you unbelievably high returns in an extremely short period of time, chances are good they’re offering you a Ponzi scheme, and if you take the bait, you can kiss your money good-bye.

The infallible forecaster

Any time you receive a letter or email from a stranger who says he wishes to help you for no apparent reason, watch out. Many con games start by offering a victim something for nothing, which plays to the victim’s inevitable greed (proving the adage “You can’t cheat an honest man”).

In the “infallible forecaster” investment scam, a “broker” visits an investment chat room or forum and sends an email to everyone he finds there, offering an investment prediction at no charge whatsoever. The email says the purpose of the offer is simply to demonstrate the broker’s skill at forecasting the market. The free forecast will tell you to watch a particular stock or commodity, and sure enough, the price will go up, just as he said it would.

Soon you’ll get another message from the same broker, containing the prediction that a stock price or commodity is about to drop. Once again, he just wants to convince you of his infallible forecasting abilities—and once again, the price will do exactly what was predicted.

After that, you’ll receive a message with a third prediction, but this time you’ll have a chance to invest. Because the broker’s previous two predictions seemed accurate, many people will jump at this shot at a sure thing. Then the broker takes his victims’ money and disappears.

Here’s what really happened. For the first mass-emailing campaign, the broker contacted 100 people. In half of those letters, he claimed a stock or commodity price would go up; in the other half, he claimed that the price would go down. No matter what the market does, 50 people will probably believe that the broker accurately predicted it.

With these 50 people, the broker repeats the process, telling 25 of these people that a price will go up and 25 of them that the price will go down. Once more, half of the scammer’s potential victims will receive an accurate forecast.

So now the con artist has 25 people (out of the original 100) who’ve seen evidence that he can accurately predict the market. They send the broker their money—and never hear from him again.

The next time you visit an investment-related chat room, newsgroup, or website, remember that you will likely become a target for the con artists who specialize in these kinds of investment scams. So, be careful, keep your money to yourself, and warn others of investment scams. Be vigilant about applying common sense to every offer, and you should be all right.

The Lonely Hearts Scam

The lonely hearts scam involves fleecing a rich victim with the promise of love and affection. In the old days, the con artist had to meet and talk with the potential victim in person, but nowadays, con artists can use the Internet to work their magic from afar.

The con artist contacts potential victims and claims to be a beautiful woman currently living in another country such as Russia or the Philippines. After sending a photograph (usually of someone else), the con artist steadily gains the trust and confidence of the victim through emails, faxes, or letters.

When the con artist believes he has gained the victim’s trust, he makes a simple request for money to get a visa, so the foreign pen pal can travel to meet the victim—purportedly to live together happily ever after. If the victim sends money, complications inevitably arise requiring more money for bribes or additional fees, as in the Nigerian scam.

Sometimes the victim realizes he’s been fleeced and stops sending money, but other times the victim honestly believes that the con artist is a beautiful woman trying to get out of her country. The longer the con artist can maintain this illusion, the more money he can fleece from the victim.

Internet-Specific Con Games

Many con games have been around for years, but others are brand new, created in the wake of the development of the Internet. The primary con game on the Internet involves stealing credit card numbers. Con artists have several ways of doing this: packet sniffing, web spoofing, phishing, using keystroke loggers, and using porn dialers. (Some of these methods have been covered in previous chapters.)

Packet sniffers

When you send anything over the Internet (such as your name, phone number, or credit card number), the information doesn’t go directly from your computer to the website you’re viewing. Instead, the Internet breaks this information into packets of information and routes it from one computer to another, like a bucket brigade, until it reaches the computer hosting the website you’re sending the information to.

Packet sniffers work by intercepting these packets of information. Typically, a hacker will plant a packet sniffer on a computer hosting a shopping website. The majority of packets intercepted on that host computer will contain credit card numbers or other information a thief might find useful.

The packet sniffer copies the credit card number before sending it to its final destination. Consequently, you may not know your credit card number has been stolen until you find unusual charges on your bill.

To help protect yourself against packet sniffers, only type your credit card number into a website that uses encryption (a tiny lock icon appears on the screen, usually at the bottom right, when you’re connected to an online shopping site that uses encryption).

Despite current public perception, the Internet isn’t the easiest vehicle for stealing a credit card number. When you use your credit card in a restaurant, the waiter could copy down the number for his own personal use later. That’s much easier than the time and trouble it takes to install a packet sniffer. A bigger threat to your credit card actually occurs when a company stores it on its (usually insecure) computer. Hackers can break into that computer and steal all the credit card information stored there, including yours, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

In 2005, intruders broke into the network of CardSystems Solutions, a company that processed credit card orders for MasterCard, Visa, Discover, and American Express. The hackers copied the records of more than 200,000 credit card holders. That same year, scammers hoodwinked ChoicePoint, a company that provides consumer data to insurance companies and government agencies, and stole more than 110,000 records containing names, addresses, Social Security numbers, and credit reports. Even Stanford University fell victim to a hacker who broke into the school’s computers and took more than 10,000 records containing names and Social Security numbers. No matter how safe your computer may be, your data stored elsewhere will always be at the mercy of others’ computer security.

Web spoofing

Web spoofing is similar to packet sniffing, but involves setting up a website that masquerades as a legitimate site. To attract victims, con artists may rely on common misspellings of a URL address. For example, someone trying to visit Microsoft’s website at www.microsoft.com might type www.micrsoft.com by mistake and access what appears to be the legitimate site they wanted. But any credit card number sent to this site goes directly to the con artist.

To prevent yourself from falling victim to web spoofing, always verify the correct spelling of a URL address in your browser window. To play it safe, rather than type a URL address yourself, visit a search engine to find the website you want, such as Microsoft or eBay, and follow the link displayed in the search results. Bookmark commonly used pages so that they don’t have to be typed often.

Phishing

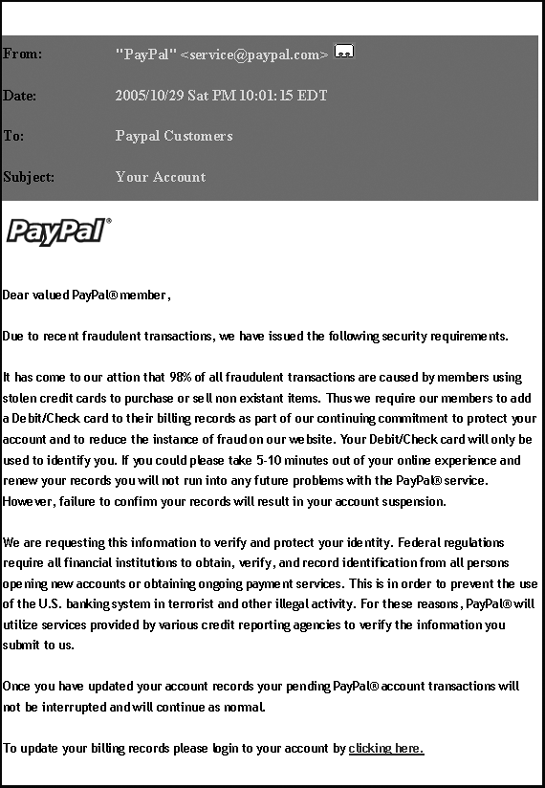

Rather than wait for someone to mistype a URL address, however, most con artists actively phish for victims by sending out bogus emails claiming to be from a bank, eBay, PayPal, or other legitimate organization, as shown in Figure 13-2.

The tone and content of phishing emails are always the same. First, they warn that users must update their account by typing in some valuable information, often a credit card number. To lend a sense of urgency, the email also threatens that the account could be suspended if action isn’t taken. Finally, the email provides a convenient link that leads to a seemingly legitimate web page where the victim can type in his credit card number. Victims enter their credit card numbers and unknowingly give that information to a con artist.

To prevent yourself from falling victim to web spoofing, always verify the correct spelling of a URL address in your browser window. To play it safe, rather than type a URL address yourself, visit a search engine and find the website you want, such as Microsoft or eBay, and follow the link displayed in the search results.

Even then you can’t always be sure that you’re visiting a valid website. Many phishers now take advantage of the way browsers interpret international characters such as the ă or ğ characters in something known as the International Domain Name (IDN) vulnerability.

Phishers simply create a fake website that mimics a real one, such as PayPal’s site. Then they give this fake website the domain name identical to the real one, except they substitute international characters, such as www.păypăl.com. When victims visit this site, the browser can’t display the international characters, so the address appears with the international characters stripped away, as www.paypal.com. Ironically, the only browser immune to this type of spoofing is Internet Explorer, simply because Microsoft never bothered to update their browser to handle International Domain Names.

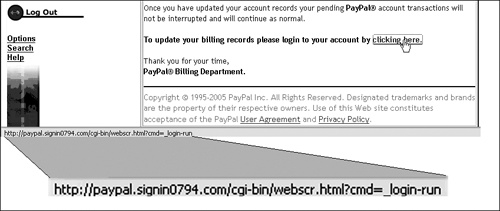

You can often recognize phishing emails by misspellings in the text, as seen in the words attion and non existant in the phishing email in Figure 13-2. Another way to recognize a spoofed website is by examining the link provided in the email. If you move your mouse pointer over the link, your browser will display the actual URL address to which the link points. As shown in Figure 13-3, spoofed websites typically embed the name of the company (such as PayPal) in the URL address along with words such as signin to create the illusion of legitimacy. However, the legitimate business’s domain is not the actual domain of these phishing sites, such as http://paypal.signin0794.com.

If a URL address contains a bunch of letters and numbers that don’t seem to make any sense, chances are good it’s taking you to a con artist’s website.

Since most experienced computer users have received numerous phishing messages purporting to be from PayPal or eBay, it’s getting harder and harder to scam people this way. So, phishers are getting more selective about whom they target, a tactic known as spear phishing.

Unlike ordinary phishers, who indiscriminately send out messages claiming to be from organizations such as PayPal or a national bank, spear phishers send their messages to a select group of individuals, typically those working for a large company such as General Motors or a government organization such as the Department of Agriculture. The messages appear to come from an existing group or department within that organization, asking for a user name or password to gain access to the corporate network. Because the bogus email appears to come from another company department, people are more likely to respond and get conned.

To learn more about phishing, visit the Anti-Phishing Working Group (www.antiphishing.org). To avoid falling victim to the latest phishing scam, grab a copy of PhishGuard (www.phishguard.com), which contains a database of bogus website addresses that phishers use to mimic other companies’ websites, such as CitiBank or eBay. The moment PhishGuard detects that you’re visiting a phishing site, it alerts you. PhishGuard stays up-to-date and effective by having users submit the latest sites to its database.

Keystroke loggers

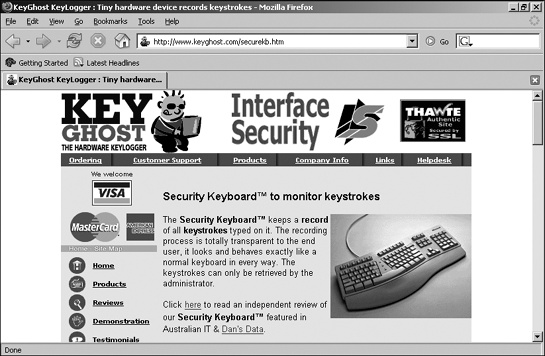

A keystroke logger is special software or hardware that records a user’s keystrokes, such as the characters a person uses to enter a password or credit card number. Software keystroke loggers run like other programs, except they hide in memory. Hardware keystroke loggers connect between the computer and the keyboard. Visit KeyGhost (www.keyghost.com) to view examples of different hardware-based keystroke loggers, including one disguised as a normal keyboard, as shown in Figure 13-4.

If a hacker doesn’t have physical access to your computer, he can still install a keystroke logger by using a remote-access Trojan horse or RAT (see Chapter 5). The con artist simply contacts potential victims through email or chat rooms and convinces them to download and run the Trojan horse, which opens a port and contacts the hacker. Then the hacker can read any files on the victim’s computer or watch the keystrokes the victim types without his knowledge.

To protect yourself against keystroke loggers, buy a program such as SpyCop (www.spycop.com) or Who’s Watching Me? (www.trapware.com). These programs will scan your computer for signs of keystroke loggers and root them out.

Porn dialers

Porn dialers won’t steal your credit card number. Instead, they use another method to empty victims’ bank accounts. Porn dialers get their name from the fact that they often claim to be free programs that grant access to pornographic websites.

Once you download this “free” program, it takes control of your telephone modem, turns off your computer’s speakers, cuts off your local Internet connection, and then secretly dials a long-distance number to connect you to another Internet service provider (ISP), typically located in a faraway land, such as Africa or Eastern Europe.

As far as the victim can tell, the program does exactly what it claimed; it provides access to free pornography. What the victim doesn’t know is that his Internet connection is now on a long-distance phone call to a place halfway across the world. The longer the victim views the pornographic files, the longer he stays connected to this foreign Internet service provider, which may ring up toll charges of several dollars a minute. The customers don’t realize they’ve been scammed until they receive their phone bills. Because the calls were initiated from the victim’s end, it’s difficult to get the charges removed from the phone bill.

Although porn dialers won’t work if the victim connects to the Internet using a cable or DSL modem, they can fool anyone still using a phone modem with a dial-up connection. If you have an external modem, watch the status lights to make sure your modem doesn’t disconnect and then mysteriously reconnect all by itself. If you have an internal modem, your only defense generally is to be careful if a website lures you into downloading “free” software with pornography. (Besides, you should already be suspicious of anyone offering you something for free when you haven’t even asked for it.) If the phone line is used only for the computer, you may be able to remove all long-distance and pay-per-call access by requesting this from the phone company. That option must be implemented before charges show up, however.

Online Auction Frauds

One of the more recent crazes on the Internet is online auctions where people can offer junk, antiques, or collector’s items for sale to anyone who wants to bid on them. Millions of people visit online auction websites (such as eBay), making them a tempting target for con artists. Sellers often have to deal with fraudulent bids from people who have no money or intention of buying. Buyers have to watch out for con artists selling fraudulent or nonexistent items.

The simplest con game is to offer an item for auction that doesn’t even exist. For example, every Christmas there is a must-have toy that normally costs about $10 to purchase, but because of its scarcity in stores, it can cost up to several thousand dollars when purchased from a private seller. Many con artists will claim to offer such a product, and then disappear once they’ve got their victims’ money.

Misrepresentation is another common online auction fraud. Con artists may sell counterfeit collector’s items such as autographed baseballs or sports jerseys. To protect yourself against online auction fraud, follow these guidelines:

Identify the seller and check the seller’s rating. Online auction sites such as eBay allow buyers and sellers to leave comments about one another. By browsing through these comments, you can see if anyone else has had a bad experience with a particular seller.

Check to see if your online auction site offers insurance. eBay will reimburse buyers up to $200, less a $25 deductible.

Make sure you clearly understand what you’re bidding on, its relative value, and all terms and conditions of the sale, such as the seller’s return policies and who pays for shipping.

Consider using an escrow service, which will hold your money until your merchandise arrives safely.

Never buy items advertised through spam. Con artists use spam because they know that the more email offers they send out, the more likely they’ll run across a gullible victim. If someone’s selling a legitimate item, he’s more likely to go through an online auction site.

The Scambusters website (www.scambusters.org/Scambusters31.html) offers additional sage advice:

Don’t conduct business with an anonymous user. Get the person’s real name, business name (if applicable), address, and phone number. Verify this information before buying. Never send money to a post office box.

Be more cautious if the seller uses a free email service, such as Hotmail or Yahoo!. Of course, many people who use these services are honest, but Hotmail and its ilk also make it very easy for the seller to keep his or her real identity and information hidden.

Always use a credit card (not a debit card, cash, or money order) for online purchases. If there’s any dispute, you can have the credit card company remove the charges or help you fight for your product.

Save copies of any email correspondence and other documents involved in the transaction.

Credit Card Fraud

Credit card fraud is actually a bigger headache for merchants than it is for customers. If a thief steals someone’s credit card and orders thousands of dollars worth of merchandise, the merchant pays for the loss, not the owner of the stolen credit card.

So if you’re a merchant, be extra careful when accepting credit card orders. To help protect your business, follow these guidelines:

Validate the full name, address, and phone number for every order. Be especially vigilant with orders that list different “bill to” and “ship to” addresses.

Watch out for any orders that come from free email accounts (hotmail.com, juno.com, usa.net, etc.), which are easy to set up with phony identities. When accepting an order from a free email account, request additional information before processing the order, such as an alternate email address, the name and phone number of the bank that issued the credit card, the exact name on the credit card, and the exact billing address. Most credit card thieves will avoid such requests for additional information and look for a less vigilant merchant to con.

Be especially careful of extremely large orders that request next-day delivery. Thieves usually want their merchandise as quickly as possible—before they’re discovered—and don’t mind adding a bit to the overall charge, which they aren’t planning to pay anyway.

Likewise, be careful when shipping products to an international address. Validate as much information as possible by email or, preferably, by phone.

For more information about protecting yourself from credit card fraud and other online thievery, visit the AntiFraud website at www.antifraud.com.

Protecting Yourself

To protect yourself from scams in general and online scams in particular, watch out for the following signs of a scam:

Promises of money with little or no work.

Requirements of a large payment in advance before you have a chance to examine a product or business.

Guarantees that you can never lose your money.

Assurances that “This is not a scam!” along with specific laws cited to prove the legality of an offer. When was the last time you walked into a supermarket or a restaurant and the business owner had to convince you that you weren’t going to be cheated?

Ads that have LOTS OF CAPITAL LETTERS and punctuation!!! or that shout “MIRACLE CURE!!!” or “Make BIG $$$$$ MONEY FAST!!!!!” should be viewed with healthy skepticism.

Hidden costs. Many scams offer free information, then quietly charge you an entrance or administrative fee.

Any unsolicited investment ideas that appear in your email inbox.

To learn more about scams, visit your favorite search engine and look for the following strings: scam, fraud, pyramid scheme, ponzi, and packet sniffer.

For more information about protecting yourself, you can contact one of the following agencies.

Cagey Consumer

This website offers updated information about the latest promotions, offers, and con games (http://cageyconsumer.com).

Council of Better Business Bureaus

Check out a business to see if it has any past history of fraud, deception, or consumer complaints filed against it at the Better Business Bureau website (www.bbb.org). If you have been the victim of a scam, instructions for reporting it are available through this website.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The FBI runs its own Internet Crime Complaint Center (www.ic3.gov). By visiting the FBI’s regular website, you can find the latest news about the most recently uncovered frauds (www.fbi.gov).

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

Information about consumer protection rules and guidelines that all businesses must follow, along with news on the latest scams, are available from the Federal Trade Commission (www.ftc.gov).

Fraud Bureau

The Fraud Bureau is a free service established to alert online consumers and investors of prior complaints against online vendors, including sellers at online auctions. It also provides consumers, investors, and users with information and news on how to surf, shop, and invest safely on the Net (www.fraudbureau.com).

ScamBusters

ScamBusters provides information regarding all sorts of online threats ranging from live and hoax computer viruses to con games and credit card fraud. By visiting this website periodically, you can make sure you don’t fall victim to the latest Internet scam (www.scambusters.org).

Scams on the Net

For multiple links to various scams circulating around the Internet, which you can search through to make sure any offers you receive aren’t scams that have tricked others, visit this website (www.advocacy-net.com/scammks.htm).

ScamWatch

ScamWatch provides a forum where people can share and discuss the latest cons circulating around the Internet. By talking with others, you can learn how to avoid becoming the next victim (www.scamwatch.org).

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

The SEC regulates securities markets and provides investing advice, information on publicly traded companies, warnings about investment scams, assistance to investors who believe they may have been conned, and links to other federal and state enforcement agencies. If you’re one of those boomers flinging money into the stock market, check it out (www.sec.gov).

The Recovery Room Scam

“Been Ripped Off? We’ll Get Your Money Back!”

After getting ripped off by con artists, many people want nothing more than to get their money back. That makes them easy prey for another kind of scam, known as a recovery room scam. Con artists get the names of people who have been conned and call or send them email, claiming to be federal attorneys or agents who can recover all or part of their lost money for a fee.

Victims are usually so eager to get their money back that they willingly pay this fee up front, not realizing that they’ve just been ripped off by another set of con artists (or possibly even the same one that ripped them off in the first place). Naturally, the victims never get their money back from either con. Recovery room scams can be particularly insidious because they can keep victimizing the same people over and over and over.

Just remember: You can’t get something for nothing. If you want to get something for nothing, do the honest thing and become a dishonest politician. Then you can make laws for your financial benefit and claim that it’s perfectly legal.