About this Chapter

Planning is the part of strategic cost analysis that is crucial to decisions on corporate strategy. Your ability to plan and control the costs of activities for which you have responsibility is essential to ensuring that organizational strategy is viable and capable of being pursued successfully. In this chapter, we explain the planning process and your probable involvement. In the next chapter, you will learn how to use the financial information generated from the techniques we discuss here to monitor and control your own responsibilities.

Strategic cost planning will involve the consideration of various scenarios and determining which plans will attain the desired objectives. To achieve both short-term and long-term goals, progress toward them must be monitored and controlled by managers regularly comparing and analyzing actual performance against the plans.

In your organization, you will find that one or both of the two techniques explained in this chapter are used. Standard costing concentrates on the daily operations and the continued achievement of short-term goals. Although a method routinely used in large manufacturing organizations, it can also be used in the service sector. The technique is very close to the daily production process and the relationship between inputs and outputs.

Budgetary control is concerned with the proposed strategy over a longer time period. The long-term strategy is determined, usually for one year, and periodic monthly subgoals set toward the proposed strategy. Budgetary control, in various forms of sophistication, is found in nearly all types and sizes of organizations. It would be unusual for a manager not to be monitoring and controlling the activities for which they are responsible without a budget. It is also the one topic where the application of performance measures and human behavior are most frequently observed.

In this chapter, we first explain standard costing and discuss the different aspects of setting the standards and where you may be involved. Because of the importance of budgetary control in most organizations, the concepts and principles of the subject will be a major part of this chapter.

Standard Costing

Key Definition

Standard costing is a system of cost ascertainment and control in which predetermined standard costs and income from products and operations are set and periodically compared with actual costs incurred and income generated in order to establish any variances.1

Standard costing is a long established practice and has been strongly linked to the manufacturing sector. It is claimed that the technique was implanted in the UK after the First World War and developed further in the 1940s. Although the practice in the United States has been more widespread, there is no evidence that it is more advanced in that country.2

Despite the introduction of new techniques that we discussed in the previous chapter, the surveys that have been conducted show that it is in operation in a majority of firms in Malaysia,3 and its use has not declined in a large number of firms in both developing and developed countries.4

We suggest that the main reasons for the continued success of standard costing are that it is relatively easy to understand and provides information that can be understood and acted upon by managers. Taking a simple example, managers need to plan the cost to manufacture an item. This allows them to determine the selling price and the profit they expect to make. If the actual cost incurred is different from what is planned, managers need to understand the reasons so that action can be taken. In the following sections, we explain:

•How to set standards

•Calculating the reasons for any difference between the planned and the actual cost

It is important to bear in mind that in conducting an analysis, the total cost of a resource is a result of two factors: the usage or quantity of that resource and the price per unit of that resource. If we are going to conduct an analysis that captures the interaction of these two variables, we need a technique that does the same. Standard costing allows us to conduct a detailed analysis of the factors.

In the previous chapter, we noted that process costing, in many organizations, is accompanied by standard costing to ensure that managerial monitoring and control of costs are achieved. Standard costing therefore sets out certain levels of performance and measures actual performance against that standard. Any difference, known as a variance, is investigated.

Standards can be set for various activities, but in this section, we will use material and labor costs as exemplars, as they illustrate the technique and are the standards most commonly found. You may not be involved with material and labor costs, but the principles we demonstrate are transferable to other areas of activity. In the next chapter, you will learn how to analyze the information arising from the standard costs of other activities.

Note that in the aforementioned definition, reference is made both to the costs incurred and to the income generated. Standard costing is used to examine differences between the planned revenue and actual revenue and not only to investigate costs. In our discussions, we explain how standard costing can be applied to the revenue.

To establish standards of performance for an organization, the working conditions must be defined and a decision made as to whether ideal or attainable standards should be set. Ideal standards are based on the best possible working conditions and usually assume that operations are at full capacity with no wastage, breakdowns, or idle time. Although ideal standards present a rigorous approach, the fact that they are unlikely to be achievable, can demotivate employees and distort the strategic plans. Attainable standards are more widely used because they are based on realistic efficient performance and allow for potential, but acceptable, deviations from perfect performance.

The philosophy and strategic and financial sophistication of an organization will determine the approach to its standard setting. Some of these approaches do not have any analytical basis and are little more than repeating past mistakes, as you can conclude from the following list.

•A prior period’s level of performance. Although this may reflect the successes of the past, it may also include the deficiencies and not take into account changes in both internal and external conditions that may have taken place.

•The levels achieved by comparable organizations. This is a more analytical approach and has certain competitive attractions, but caution must be used to ensure true comparability.

•A backward-looking assessment of what should have been achieved. This “after the event” approach rarely provides credible data for monitoring and control.

•The levels of performance that the company wishes to achieve in order to pursue its strategic plans.

You need to understand the basis used by your organization to set standards, as this represents the performance levels you are expected to achieve. You may find that your organization involves you fully in setting the standards for your area of responsibility or asks you to comment on the feasibility of the standards set.

To integrate usage and price, the standard cost is the planned unit of cost that is calculated from technical specifications and economic and market conditions. The technical specifications specify the quantity of materials, labor, and other elements of cost required, and these are then related to the prices and wages that are expected to be in place during the period when the standard cost will be used.

To determine the appropriate standard for both usage and price of a resource, a careful analysis must be conducted on a range of information. To set standards for materials and labor, the organization will refer to the following:

•Materials: quantity and price

◦Analysis of past data

◦Job specifications, which should list required materials

◦Engineering plans that provide a list of materials

◦Recipes or other documents specifying materials required

◦Time and motion studies

◦Price lists provided by suppliers

◦Expected economic environment

◦Predicted actions of suppliers, competitors, and customers

•Labor: quantity (hours) and rate

◦Analysis of past data

◦Time and motion studies

◦Contracts that set labor rates

◦Prevailing rates in the area or industry

◦Expected economic environment

◦Changes in labor supply and demand

As a procurement manager, you can expect to be involved in the materials pricing standard. As an engineer, chemist, or production manager, you will assist with the quantity of the materials. Similarly with labor standards, a range of managerial knowledge and experience may be called in to assist in setting standards.

At this stage, you will realize that standards are going to be set for the cost of the inputs, the labor, and the materials, and you therefore need to know the price for the inputs and the amount of usage for a certain level of production. The total cost of a particular input will be the amount used, multiplied by the price paid for a specific quantity of that output.

Applying this principle, the use of 30 meters of a particular material at $2.00 per m, will have a total cost of $60.00.

One difference in setting standards is that for labor. With this input, we are interested in the planned time that direct labor will take to complete a certain volume of work. This is usually measured in standard hours or standard minutes. The important point is that a standard hour is a measure of production output, rather than a measure of actual time. For example, a company may determine that 600 cost units should be produced in 1 hour. In a 7-hour day, the actual total production is 4,800 cost units. That actual output can be converted into standard hours as follows:

4,800 units/600 = 8 standard hours of production.

You will appreciate that if you have managed to achieve 8 standard hours of production in 7 actual hours, labor is being very efficient. In the next section, we will examine how this achievement can be measured in financial terms and integrated into a cohesive analysis of the activities.

Calculating the Variances

A variance is the difference between the standard or planned level of performance and the actual performance achieved. In this case, we are interested in analyzing the cost performance. To do this successfully, we need to know the interaction between the usage and price of a resource to give the total cost.

A simple example will demonstrate the calculation of the standard and the variance. Suppose that you intend to make some fruit juice, and you decide to buy oranges. Your investigations establish that you require 50 pounds of oranges for the quantity of juice you want. A survey of fruit suppliers shows that the price would be $1.20 per pound. The total cost to you would therefore be: 50 pounds × $1.20 = $60, and this is your standard. Unfortunately, when you buy the oranges, you find they are of an inferior quality. Now, you need 60 pounds, but the price is only $1.10 per pound, giving a total cost of $66.

Say that you compare your total material cost to your standard, and you have an adverse or unfavorable variance of $6.00 because you paid more in total than you planned. This can be expressed using the following formula:

(standard quantity × standard price) – (actual quantity × actual price)

(50 pounds × $1.20) – (60 pounds ×$1.10) = $6.00 unfavorable (U).

At this stage, we have information on the total cost, but we need to pursue our analysis further. We need to know the financial consequences of buying more oranges than you planned (a quantity variance) and that of paying less per pound than you planned (a price variance). The following formulas can be used:

quantity variance: (SQ – AQ) × SP = (50 – 60) × $1.20 = $12.00 U

price variance: (SP – AP) × AQ = ($1.20 – $1.10) × 60 = $6.00 F.

The two subvariances of quantity and price can be netted off to give the total variance. In this example, we have referred to a quantity variance. In some organizations, they will calculate the amount of materials purchased, not necessarily used, and in others they will calculate the actual usage and refer to it as the usage variance.

The more detailed analysis informs us on the interaction between the usage and price of the resource on the total cost. From this, we can make decisions on the quality of materials we are using and the price we have to pay for each unit of the material.

In the next chapter, you will learn how to calculate and analyze variances: the differences between the standards set and the actual performance achieved. It is this information that contributes to strategic cost analysis. At this stage of setting the standards, you will appreciate that there are many organizational benefits to be gained:

•The practice of using past performance as a guide is removed, and the standards demonstrate the strategic plans of the organization.

•Standards are set for future activities, and they encourage managers in making decisions aligned to strategic priorities.

•Implementing standards requires a thorough examination of the organization’s production and operations activities. Every stage in production is minutely examined, and the most cost-effective and efficient procedures are established.

•Responsibility for performance is identified with specific managers.

•A viable and credible benchmark is established, against which actual performance can be compared.

•The setting of standards encourages the coordination and integration of the various functional activities.

•The regular updating of standards encourages a continuous review of activities.

•Where managers are properly trained (as they should be) in the investigation and analysis of standards, they will become more effective.

Although standard costing offers many organizational benefits, there are aspects that you need to consider when assessing the implementation and maintenance of the system:

•In a turbulent economic environment or where the organization is breaking new frontiers, it may be impossible to gather sufficiently robust data to set viable standards.

•Even with a fairly simple system, implementing and updating a system can be costly.

•If any of the standards become out of date or lose their relevance, the entire system has reduced its credibility.

•Busy managers may suffer from information overload and ignore the data.

One of the considerable advantages of standard costing is its flexibility in application. You need not have a full-blown system covering all aspects of the organization. You may only set standards for material usage if that is a significant cost and you wish to ensure tight control. In the following chapter, we cover a wide range of different standards. It is important that you are selective in the standards that are of benefit to you. Also remember that there are other control methods that may be more appropriate in certain conditions.

Budgetary Control: Overview

The importance of budgets to strategy formulation cannot be overemphasized. A recent study found that in most organizations the budget process is explicitly linked to strategy implementation. Indeed, budgeting was identified as an important means for implementing strategy.5 As a manager, in probability, you will be involved in establishing the budget for your area of responsibility.

A budget is a financial representation of the strategy of an organization. In constructing a budget, a careful analysis of all planned costs needs to be conducted and the choice of alternative courses of action assessed.

A typical budget:

•relates to a defined time period (usually 12 months divided into shorter periods)

•is designed and approved well in advance of the period to which it relates

•shows expected income and expenditure

•identifies responsibility levels for various parts of the budget

•includes all capital and revenue expenses likely to be incurred in furthering the organization’s strategic objectives

•is not an accounting exercise but a managerial planning and control system

Functional budgets will be constructed based on departments or some other identifiable area of activity. These functional budgets will be integrated to form the master budget that encompasses all the organization’s operations and activities.

To ensure monitoring and control of actual performance against the budget, an analysis of differences arising between the actual and planned performance needs to be conducted regularly. Managers responsible for governing costs allocated to their centers should investigate any differences. You will learn in the next chapter how to assess and investigate these variances.

We emphasize that a budget should be released well in advance of the financial period. It is understood that this will not occur until the board or governing body of the organization has given its approval. Because of the substantial amount of work required in generating, integrating, and obtaining approval of the budget, they are sometimes issued after the financial period has commenced. Unfortunately, all too commonly managers spend the first few months of a new financial period working to an informal budget or even using last year’s budget as a benchmark.

If your organization is not efficient and issues budgets after the start of the operating period, you are at a disadvantage. Without the details of the organizational strategy that are encompassed in the budget, you have no platform to manage successfully. If you are working in such an organization, make it very clear to your superiors on what basis you are using as a plan. It may be the budget for last year or the actual performance for last year. Do not fall into the trap of agreeing to manage as best as you can.

Advantages of Budgetary Control

You now have the broad picture of what budgetary control is about, but you may wonder whether all the work involved is of benefit. We return to that issue at the end of the chapter, but we first consider the advantages of budgetary control:

•Strategic formulation and implementation are enabled by the formal planning process.

•Control and assessment of actual performance are ensured by the regular and frequent comparisons with planned performance.

•Corrective action can be taken in a timely manner where actual performance is unacceptable, or unforeseen economic events intrude.

•Coordination of the various organizational functions is established.

•Communication to all managers of organizational objectives and progress toward them is achieved.

•Responsibility of managers for the performance of activities and functions within their control is clearly determined and reported upon.

•Consensus on organizational objectives and motivation to achieve them is developed through a carefully conducted budgetary control process.

•A comprehensive analysis is conducted of all costs incurred by the organization.

Approaches to Budgetary Control

Most advice is that budgetary control is improved in an organization where the process is participative; managers are involved in establishing the budgets for their own particular function or level of responsibility. In practice, it is frequently less clear how this is to be achieved and the benefits of coordination of activities enjoyed within a reasonable time period.

Setting budgets takes a significant amount of your managerial time, and the greater the amount of discussion and participation, the longer the process is likely to take. One of the requirements of a good system of budgetary control is that the budgets are prepared, agreed, and disseminated prior to the commencement of the financial period.

This will mean that you are trying to make plans for a future period. If the budget period starts in January 2018, you may be asked in October 2017 to contribute to setting the plans for your own area for the forthcoming year. In other words, in October 2017, you will be attempting to determine your activities for the months of October, November, and December 2018, as well as the preceding months. This is a test of your managerial skills and the issues you should assess are the possible

•changes in the size of the organization’s market and its market share

•competitors’ strategies

•changes in interest rates or exchange rates

•sources and costs of external funding

•changes in costs and availability of energy, materials, and labor

•changes in legislation, social pressures, environmental concerns that will affect the organization

•effects of the activities of other related organizations

•changes in climate, consumer demographics, or foreign political powers

•actions and influences of global bodies

You will appreciate that setting budgets is not merely about predicting the future. By setting out the organizational financial and managerial strategies and the actions that must be taken to achieve them, managers at all levels are making business plans that help meet the financial objectives.

The approach to budgeting will depend on a number of factors from the prevailing style of management to the funding of the organization. We discuss three approaches found in practice. You should bear in mind that in some organizations, all three approaches may be operating simultaneously in different parts of the company.

Top–Down Budgets

With this approach, budgets are determined at the most senior level in the organization and there is little or no participation by managers. You will find that most textbooks decry this approach to budgeting, but there are specific reasons why you find this in practice. Because academics may find that it does not correspond with their managerial philosophy, does not mean that the system is of no value to the organization. We have identified the following reasons for the top–down approach.

Managerial Style

There are senior managers who believe that it is their responsibility to manage and that authority is held at the top positions in the organization. In a particularly turbulent economic environment, decisions may need to be made quickly, and participative budgeting may enhance the decision-making process, but it will undoubtedly slow it down.

Sources of Funding

Many organizations do not have control of the generation of their own revenue. If you consider government organizations, they rely on tax dollars for their funding. Usually, departments and various bodies will carry out political lobbying to obtain their share of the tax revenue. The decision on the allocation is made at the top and will often be passed down together with a list of priorities that must be achieved. The opportunity for managers to participate in the allocation is constrained by the political decisions.

Similarly, organizations such as charities and art, community, sport, and other groups will be heavily reliant on donations and bequests. Although considerable effort may be made to improve the inflow of dollars, to a large extent budget strategy will concentrate on spending the dollars effectively under the mandate they have.

The Markets

It is easy to forget that directors are not making decisions in a vacuum. They are answerable to their shareholders and, possibly more dauntingly, the analysts and the stock markets. Also, the performance of the organization, as measured by earnings and various ratios, will be compared to its competitors. The market will have certain expectations, and the board must shape its strategic plans to meet, and if possible beat, these expectations.

Company Size

There is evidence from the UK that in businesses of 10 to 15 employees, the owner-managers impose budgets, if there are any, that must be rigidly adhered to by junior managers.6 One would anticipate that, in many small businesses, budgetary control is basic, and the full concentration may be on the cash inflows and outflows, and owners may consider that private information.

Although we can identify reasons for top–down budgeting, it does have its problems. Frequently, managerial initiative is heavily constrained by the requirement to comply with the budget. You may find yourself becoming demotivated and not search for savings or ways to improve the performance of the company. If you understand the principles and procedures of budgetary control, as explained in this book, you can make a valuable contribution to your company’s success, which is usually recognized.

Bottom–Up Budgets

With this approach, budgets are gradually built up from input from the managers most closely connected with particular activities and functions. The arguments in favor of this approach are strong but not totally persuasive. The philosophy is that full participation by those most closely affected by the budgetary control system will lead to more realistic plans, employees will be more highly motivated and organizational performance will be improved.

There are examples where organizations have encouraged a high degree of employee participation in the budgetary control system and have apparently enjoyed improved performance. Of course, these examples are often of companies that are well organized and financially secure. It can be difficult to prove that participation in budgets was the sole reason for success. Sometimes, where a company has been in financial distress, working cooperatively with employees has turned the company around. Closer examination will usually show that the success may be more likely due to agreed wage cuts, and thus reduced labor costs, and efficiency and productivity improvements that needed to be introduced in any event.

Scenario Planning

In various forms, organizations have found that this approach permits participation, enhances integration, maintains a strategic approach, and can be accomplished within a reasonable time frame. The first stage is for senior managers to obtain forecasts, often from external agencies, of various economic indicators, such as exchange rates, inflation, market growth or decline, material availability, or consumer confidence.

For the next stage, an organization may select one scenario or alternative scenarios and the strategies that could be pursued. This information is then distributed to managers for their inputs. Depending on the company’s policy, the managers may be able to select the scenario or strategy they find it most credible. Having made this selection, the manager then establishes the budget for his or her section.

The less choice of scenarios and strategies that the manager can select from, the quicker the process and the easier to attempt to integrate the various management inputs into one cohesive master budget.

It is important for managers to build into their scenario the influence of external agencies. If a company is seeking external finance, there is a tendency to construct a budget that is acceptable to the financiers. If this happens the budget may be too optimistic and is unachievable. Managers within the company will quickly realize that they will not be able to perform at the level promised and the budget will fall into disrepute.

Another factor to consider is whether the organization is the recipient of any government or other external funding. It is not unusual, especially in periods of economic decline, for governments to seek cutbacks in the funding they are willing to provide. Companies should resist the temptation to make across-the-boards cuts. Difficult although it may be, the strategy must be to target those parts of the organization that are not making a useful contribution. To do otherwise will result in a lack of commitment to a budget that attempts to make general cuts throughout the organization.

Developing Budgets

Incremental Budgeting

With this type of budgeting system, the new budget is set by adding or deducting an incremental percentage to either the current year’s actual income and expenditure or the present budget. This can be as unsophisticated as merely adding a percentage to all items to allow for inflation. At a more sophisticated level, there may be varying amounts of incremental increase to recognize some required or desired changes in activities. The organization usually has assumed that it is in a stable environment where planned performance is relatively certain and consistent from one year to the next. This type of budget has the following advantages and disadvantages.

•Advantages

◦The system is simple and quick to implement.

◦Managers are not confronted by significant changes in operations and the consequent demands on their time.

◦The integration of functional budgets is maintained and interdepartmental relationships kept consistent.

◦If activities become suddenly constrained by external forces, the organization may have no choice but to cut all budgets and is therefore recognizing the reality of these constraints and can do so quickly.

◦The deficiencies in actual performance or previous budgets are repeated.

◦The assumption is that the organization is successful and will remain so. Consequently, little or no strategic planning takes place.

◦There is no motivation for managers to look for cost reduction or efficiency gains.

◦There is no effort to achieve improved performance levels.

◦There is the tendency for managers to spend their budgets to ensure they will receive an equivalent amount in the next budget.

Zero-Base Budgeting

This approach was pioneered in commercial organizations by Texas Instruments as “Objectives, Strategies and Tactics.” The concept was developed by Peter A. Pyhrr, and in a Harvard Review article he called it zero-base budgeting.7 The essence of the concept, which has changed little over the years, is that the onus is placed firmly on each manager to develop his or her budget from scratch. In other words, the costs of all activities must be justified by you as a manager from a zero base, unlike incremental budgeting where current actual performance or budget is a benchmark to which agreed increments are added or deducted.

This approach means that no operations, activities, or expenses are automatically funded merely because they already exist. This makes the budget much more relevant to the particular conditions expected in the budget period and the strategy to be pursued rather than incremental budgeting. It places a substantial demand on you as a manager to prove the valuable and essential contribution your area of responsibility makes to the organization’s success.

Organizations using zero-base budgeting will develop their own individual approach, but there are usually three main stages.

•Stage 1. The organizational objectives and strategies are spelled out in as much detail as possible. The question being asked is “What are we trying to do and how will we do it in the environment we anticipate?” You will note that the predicted environment is essential to the question. The various levels where managers will be responsible for determining the budget are identified.

•Stage 2. Managers at these levels must spell out the specific activities they will conduct to meet the organization’s strategy and the budget required. Wherever possible, alternative methods should be proposed with their costs and advantages and disadvantages. You should also incorporate your opinion on the implications of not conducting that activity.

•Stage 3. The activities and how they will be conducted at each decision level are then selected. This is usually conducted by top management to ensure the efficient integration of all the functions. You would not want the distribution department to be closed if another manager’s budget was based on the assumption that it would remain in operation!

As can be envisaged, this procedure is expensive and time consuming but does have analytical rigor. Most organizations will only implement zero-base budgeting where there are significant changes anticipated or new ventures are to be undertaken. Some organizations find it useful to conduct partial zero-base budgeting in different parts of the organization at various times. You may find it useful to carry out an informal zero-base approach on your own responsibility area. It may provide useful illumination on how to improve your performance.

Rolling Budgets

Both incremental budgets and zero-base budgets suffer from the same problem. They are set prior to the commencement of the financial year, and given the speed of change and general uncertainty in the external environment, they can soon become outdated. Assuming that much of the decision making that goes into them gets done in the fourth quarter of the prior year, by the end of the following year, traditional budgets reflect thinking and data more than 12 months old. One response to this is the use of rolling budgets.

These can take many forms but the main concept is that prior or present actual performance is used as a basis for setting budgets for near-future performance. For example, a company may be monitoring monthly performance. It will use actual performance over the last 12 months as the basis for establishing the budget for the next 3 months. As each month passes, the company extends its time frame into the future using recent actual performance as a guide.

Activity-Based Budgeting

Activity-based costing was examined in Chapter 2, and it is a logical step to move the concepts into the budgeting process. It is essentially a reversal of an ABC system. In ABC, the movement is from the resources to the activities and then finally to the products and customers. In ABB, the movement is from forecast of the products and customers to the activities to achieve this forecast and finally to the resources required to support the activities. The main difference with ABB from traditional budgeting is found in the treatment of overheads. Traditional budgeting calculates the cost of operating an organizational unit, such as a department. ABB constructs a budget based on the demands of a particular activity for resources.

A simple example using a flexed budget illustrates the principles. Compare this to earlier examples in this chapter where the concentration was on a department and the production output. Now we are concentrating on the cost driver of machine hours.

A production department has a separate maintenance function and has determined that its cost driver is machine hours, which is an ABC measure. For two financial periods, the fixed cost of the maintenance department is $30,000, and the variable cost per machine hour is $3.00. In the first financial period, it is predicted there will be 6,000 machine hours and in the second period 7,000 machine hours. The budget for the two periods is shown in Table 3.1. By using machine hours and a flexible budget, we have been able to capture the different demands on resources and the impact of variations on activity.

The claimed advantages of ABB mirror the claimed advantages of activity-based costing. You should be better able to identify the resources you require, and this will lead to realistic budgets that are closely related to strategy. It also links the resource costs to the expected outputs and defines your responsibilities as a manager over certain activities.

Table 3.1 Budget for two financial periods

Take a few words of caution: Do not be surprised if your organization does not exactly follow the models you find in textbooks. As stated in Chapter 1, organizational systems are a function of environmental and firm-specific factors. They are also there to help develop and achieve the strategic objectives of the organization.

Budget Implementation

Basic Requirements

The ability to conduct strategic cost analysis will depend on the effectiveness of the budget system. There are several criteria that should be satisfied for an effective budgetary control system. Indeed the list can be so long as to deter any organization from adopting budgetary control. We list below what can be considered to be the main features, and you should check to ascertain whether these are present in your own place of work.

•Organizational

◦A sound and clearly defined organization

◦Effective accounting records and procedures that are understood and applied

◦The recognition at all levels that budgetary control is a strategic activity and not an accounting exercise

◦Strong support and the commitment of top managers to the system of budgetary control

•Managerial

◦Managers responsibilities for areas of activity are clearly identified

◦The education and training of managers in the development, interpretation, and use of budgets

◦The participation of managers in the budgetary control system

•Procedural

◦Budget decisions are made in a timely manner before the commencement of a financial period

◦An information system that provides data for managers so they can make realistic predictions

◦The correct integration of budgets and their effective communication to managers

◦Regular feedback on actual performance against budget so that corrective action can be taken

Budget Centers

Organizations usually draw up individual budgets for each budget center. There are typically departments, functions of the business, or any other activity where a manager will be responsible for the monitoring and control of that budget center. As a manager you can expect to receive a budget and to be responsible for ensuring that you meet the budget and can explain any divergences.

A budget center can, financially, have different forms that will affect the manager’s responsibilities and the issues that have to be addressed. Table 3.2 shows the type of budget center, the manager’s responsibility, and the problems.

Budgetary control is frequently referred to as responsibility accounting, and Table 3.2 shows why. By regular financial performance reports, early feedback is provided to the manager for corrective action, performance assessment, and evaluation of strategy.

In Table 3.2, we have referred to the controllability of costs by the budget center manager. The concept and reality of controllability is hard to define, as a manager is rarely the only person in the organization that can influence certain costs. Also, some costs may be controllable in the short term but not the long term. Uncontrollable costs can usually be identified as the responsibility of senior management and often include the allocation of overheads.

Table 3.2 Budget center responsibilities and problems

As a manager, you will use the budget to work toward the strategic goals of the organization. The budgetary system therefore needs to be clear, transparent, and credible. You may find that a motivating factor is also built into the system, and managers may enjoy a bonus based on their performance against the budget.

Integrating Functional/Operational Budgets

Budgets are drawn up for individual budget centers. This allows an analysis of the costs for each center and also reflects the overall strategy of the organization. It is essential that these functional or operational budgets are integrated; otherwise, problems will arise, such as more products being made than can be sold, or the machinery or labor being unavailable to meet the planned output for the month.

The setting of functional budgets is therefore an iterative process. It is usual to start by establishing the sales budget monthly for the coming year. This will quantify the products or services to be sold and put them in financial terms. Having established the sales budget, attention can be given to the production budget. This will show the quantities needed to meet the demands of the sales budget, and a decision will be made on the inventory levels to be held.

In the next two sections, we demonstrate the first steps toward producing a sales budget and the related production budget. Our simplified structure demonstrates the principles, but in reality the process will be more complex and time consuming than our examples.

Sales Budget

The sales team will predict the quantities to be sold in different geographic areas, as this may affect the price received in overseas markets. The organization may also be offering a range of services and products, so a quantitative budget will be required for each one. The quantitative sales budget will then need to be converted into a financial budget. At this stage, the accountant may work with the sales team to determine whether there are any special taxes or import duties, volume discounts, or similar regulatory requirements that may affect selling prices. At a later stage, the accountants will also have to resolve the problems of foreign exchange rates.

With the sales budget in place, it is then possible to conduct an analysis of the costs that will be incurred on resources to achieve the level of sales. At this stage, the analysis of the costs and the decisions made must be in line with organizational strategy, and the detailed information will include such items as

•number of sales people required and the costs of salaries, cars, and other travelling expenses

•office space and equipment required

•commissions paid to agents

•special promotions and discounts

•an advertising budget for print, television, and other outlets

Having given you the scope of the work required, we will go back one stage and show an example of compiling a sales budget from outside the manufacturing sector. In this example, the sales budget needs to be constructed from the availability of certain resources. The example also demonstrates the relationship between strategy and budget development.

Example of Creating a Sales Budget

Ensafe is a consultancy that advises homeowners and commercial organizations how they can make their premises more energy efficient. There is substantial demand for their work, but Ensafe has difficulty in recruiting consultants. Last year was financially successful, and the company has now made the decision to pay higher salaries to consultants to expand their work force.

The company employs commercial premises consultants (CPs) and domestic premises consultants (DPs). The 12 CPs were paid $100,000 last year, and the 8 domestic premises (DP) consultants were paid $80,000 last year. Travel and related expenses for the consultants averages 20 percent of salaries. The cost of running the general office is $140,000 per annum.

The revenue is based on billable hours, and all consultants are expected to bill for 1,500 hours. The rate charge for CPs is $100 per hour and for DP consultants, $70 per hour. The income statement for last year is shown in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Income statement

Ensafe is considering an increase in all salaries by 10 percent and recruiting two more CP and three more DP consultants. It is expected that office expenses will increase by 5 percent. Ensafe is preparing the budget for next year and wishes to make a profit of $350,000 minimum.

The first stage that Ensafe needs to do is to calculate the budget for the total costs. To this they add the target profit to arrive at the revenue figure of $3,507,000. You will note that Ensafe has drawn up the financial statements to the nearest thousand dollars, which is the usual practice unless greater detail is required. In the budget in Table 3.4, the fees for the consultants have been calculated using the additional consultants but retaining the hourly billable rate.

Table 3.4 confirms that to achieve a profit of $350,000, revenue of $3,507,000 is required. Even with the increased number of consultants, the budgeted revenue is only $3,255,000. Merely increasing the number of consultants will not achieve the targeted profit. Ensafe may have to increase its billable rate per hour, but first the company needs to determine its strategy and what the market will accept. This will raise questions on whether the company intends to concentrate on domestic residences or commercial premises. The company also needs to assess the availability of consultants and whether the salaries being offered are sufficient inducement.

Table 3.4 Ensafe budget

Budgets both contribute toward the development of strategy and reflect the financial implication of budget proposals. It is impossible for Ensafe to prepare a credible budget without a strategy and also impossible to adopt a strategy without knowing the financial consequences.

Production Budget

Having considered the consultancy business, we return to a manufacturing organization to demonstrate the calculation of a production budget. The production manager will use the sales budget as the starting base, but a decision will need to be made to determine the amount of inventory that will be held.

Example of Creating a Production Budget

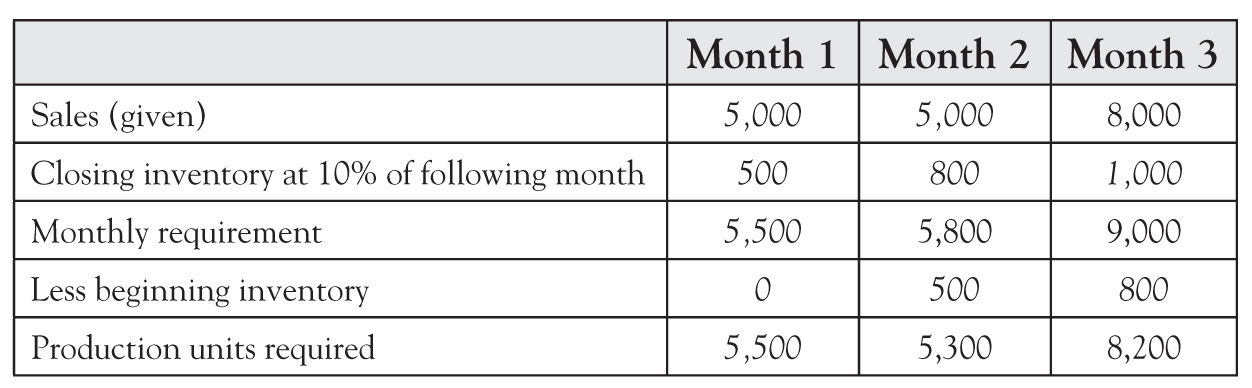

Tapcov starts a new business to manufacture covers in three sizes for cars, motorbikes, and other items. The production manager has been given the quantitative sales for the first 3 months of the year. He is also told that sales are expected to be 10,000 in Month 4. It is also agreed that he will have a closing inventory at the end of each month of 10 percent of the sales units for the following month.

You should have no difficulty in understanding that the production run in Month 1 must include the closing inventory to form the opening inventory of the next month. In Month 2, we have a total demand of 5,800, but as there are 500 units in inventory, the production requirement is 5,300 units.

Having worked out the quantities to be produced, these now need to be translated into financial terms. The production manager or the accountant may do this, and we will assume that these are the figures used:

•Materials. Each cover requires 2 meters of material priced at $1.50 per meter.

•Labor. Five covers can be made in one hour at the labor rate of $10.00 per hour.

Table 3.5. Tapcov quantitative production budgets: Quarter 1

In Table 3.6, we have considered only the direct costs. The production manager now has the problem of determining the overheads for the department—the indirect costs. There may be supervisors’ salaries, maintenance costs, and depreciation of machinery all specific to that department. The production manager can also expect that a share of the factory overheads will also be allocated to the budget. These probably will be uncontrollable as far as the production manager is concerned.

Even with this simple budget you will realize that both the procurement manager for the supply of materials and the department responsible for employment of workers must be involved. There is also the funding for machinery and the acquisition of other resources to be resolved. You will also appreciate that the more detailed the information, the better will be the analysis. There can be a tendency to concentrate on the direct production costs such as materials and labor with insufficient effort spent on the analysis of overhead costs and how these support the organizational strategy.

Because of the complexity and time taken in setting budgets, there are criticisms of the technique. But you will appreciate how it coordinates the activities of managers in the achievement of the strategic purpose of the organization. Also, regular monthly reporting of the actual performance against the budget will allow managers to take corrective action and discuss with colleagues the implications for their own departments.

Table 3.6. Production budget: Quarter 1

Financial planning is a critical aspect of strategy. In this chapter, we have explained the development of standard costs and of budgets. Standard costing is widely used in manufacturing, particularly for direct costs. We have discussed how standards should be developed from valid sources of information so that the standards have credibility. We have also indicated how standard costing is used as a basis of identifying possible reasons for actual direct costs to differ from the standard. These differences are known as variances, and we explain the calculation and interpretation of these in the next chapter.

Budgetary control is a major financial planning exercise and completely wedded to corporate strategy. We have described the different approaches that companies have and these are

•top-down budgets imposed by senior management

•bottom-up budgets where all managers participate at an early stage

•scenario planning that attempts to predict the future environment the company will operate in and allows managers to generate budgets within these parameters

There are different methods for developing budgets:

•Incremental budgeting is where the new budget is set by adding or deducting an incremental percentage to either the current year’s actual income and expenditure or the present budget.

•Zero-base budgeting is where each manager develops his or her own budget but must justify the presence and costs of all activities assuming a zero base.

•Rolling budgets can take many forms, but usually prior or present actual performance is used as a basis for setting budgets for near-future performance.

•Activity-based budgets are like a reversal of ABC, and attention is given to the costs of activities that are used to produce and sell products and services, rather than the functional department costs.

Toward the end of this chapter, we considered the procedural aspects of budgeting and the systems and committees required to implement a budget. We would emphasize that the process is extremely time consuming, and unless the budgets have credibility, managers can become disillusioned. We also used examples to demonstrate the development of budgets and their integration.

Planning is the part of strategic cost analysis that is embedded in the development of corporate strategy. It is impossible to develop budgets without a corporate strategy or to generate corporate strategy without budgets. In the next chapter, we look at standard costing and budgets from the aspect of monitoring and control of actual performance—strategy in action.

Notes

1.Hussey (1999).

2.Fleischman, Boyns, and Tyson (2008).

3.Sulaiman, Almad, and Alwi (2005).

4.Zoysa and Herath (2007).

5.Libby and Lindsay (2010).

6.Pilkington and Crowther (2009).

7.Becwar and Armitage (1998).