CHAPTER 3

Lessons Learned

Investing is not nearly as difficult as it looks. Successful investing involves doing a few things right and avoiding serious mistakes.

—John Bogle

Whether you are managing your personal portfolio or managing a billion-dollar fixed income mutual fund, your thought process as a portfolio manager must be the same. It doesn't matter the type of market, whether it is domestic, foreign, or a strategy that blends these and others together. The amount of assets you are managing, either for yourself or an end client, is also irrelevant. The focus, your success, must be centered on your disciplined approach, and most importantly, you must do your homework.

We know that history doesn't always predict the future. What it does do is provide insight that, if recognized, may become very useful.

So what type of information or insight have previous market cycles provided to us? First, back-of-the-envelope calculations show that there is a market turning point, a correction, every 10 years or thereabout. There may be more mixed in, depending on how you define a correction.

Let's go back to Black Monday, in 1987, when equity markets plummeted one Monday afternoon. Next, the dot-com bubble represented the turning point in the NASDAQ as it peaked in early 2000. Subsequently, the housing bubble popped in late 2007 and 2008, once again rattling the markets and resulting in a downward spiral for equity markets. Let me point out that two out of the three corrections were negatively felt within the equity markets. The fixed income markets traded as expected; that is, when the equity market faltered, a flight-to-quality bid occurred and flows moved into fixed income. The most recent correction that carries fresh wounds is the housing bubble, which involved the collapse of structured securities. This correction was different; I would not classify it as equity driven. This correction was fueled within the fixed income world. Unfortunately, equities were not immune and felt the pain as well.

PATTERNS EMERGE

If a timeline is constructed, the pattern that emerges is that a correction occurs approximately every 10 years. The time frame between these occurrences can easily be a coincidence. It also may just be the amount of time it takes for the next bubble to form. If we speculate for a moment, following the ten-year time frame, the next correction may occur in 2018; that is, 10 years from the 2007–2008 correction when the housing bubble broke. The year 2018 is also roughly five years from today, 2013. The potential cause of a future downturn causing the markets to spiral downward can be a wide range of events. The suspicious side of me says the European financial crisis, student loan bubble, and geopolitical events that are occurring in the Middle East involving oil-producing countries are surely on the path that could lead to the next disruption. Not to paint too much of a doom-and-gloom portrait, but there is the specter of inflation and how central banks around the world will unwind all the liquidity and cheap money that was injected over the past few years. My hope is that I am mistaken altogether. If not, let's pray that the magnitude of the disruption will be much less severe because investors around the world have had years to plan and take necessary precautions. In any event, regardless of the cause or the exact timing, the point to glean from the comments is that you should not try to time your investments. Timing or fully moving to cash would be ridiculous. The message is: always be alert. Don't just set it and forget it. Remember that statement well. This saying will come up many times throughout this book. Don't just set it and forget it; set it and monitor it. Look for the abnormalities within the markets and the changes that are occurring within the economy.

Let's revisit those painful days and the effects on the markets with the popping of the housing bubble, which commenced in 2007. A relentlessly appreciating housing market that continued to provide homeowners double-digit returns year after year created the implosion of the housing bubble and market crash. These double-digit returns allowed homeowners to refinance time and time again. In some cases, homeowners continued levering up their personal balance sheet by purchasing homes that were too large. It was the typical want and desire scenario, where the mortgage is too big for the paycheck. Additional downfalls that eventually plagued homeowners and later, the markets, were the purchases of second and sometimes even third homes. This was not prevalent in all areas of the country, but Florida, Las Vegas, and parts of Arizona were some of the hardest hit areas. There are many possible reasons for this downturn. It is difficult to point to just one problem. Many individuals, including some government officials, try to pin the start of the problem solely on Wall Street. I don't agree with this view. My opinion might be a little biased, but if you take a step back and look at all the pieces, you just may agree with me. Somehow, the media turned the root of this crisis into a battle between Wall Street and Main Street. There is so much research on the cause of the crisis that days could be spent on this topic alone. Movies have been made and will likely be made for years to come. For the purpose of this book, I will touch on different aspects of the crisis, weaving in real-life scenarios and lessons learned throughout the crisis. I will not be covering the crisis in detail.

Broadly speaking, there were two contributing factors. The first factor was all the excess risk and leverage that certain financial companies were pushing for through different investments. Second, and more important, was all the excess that occurred within the mortgage markets, primarily around lending practices. It almost felt as if greed was running wild again. The root of the problem within the mortgage market was with the lenders, who were providing loans to individuals who were not qualified to have a mortgage. Wall Street might have fueled the meltdown due to overleveraged portfolios and balance sheets, but it did not cause the crisis. The lenders and mortgage companies were awarding loans to individuals who were buying too much house and didn't have the income to support the mortgage. Believe it or not, companies were, at times, providing loans with no proof of income. It doesn't take a genius to realize that this type of lending is a disaster waiting to happen.

It has always been the American dream to own a house, and why shouldn't it be? This idea took full hold with the prime borrowers, as well as within the subprime market. The problem was that the lending activity in both prime and subprime markets included the use of adjustable-rate mortgages. Initially this was not a problem; however, when the mortgages started to reset to higher rates after the initial teaser period, some borrowers had trouble keeping up with the increased payments.

So, what happened with all these loans? Were they securitized? This was where Wall Street joined the party. Financial institutions packaged the mortgages and sold them to investors. This was not a new concept. Investors in these securities were primarily institutional investors and suffered as the different types of mortgages, tranches, and securitized products started to underperform. Some of these securities were utilized by asset managers in both the money market arena and other markets. Whose fault was it? That's a whole other discussion. Almost all sectors within the marketplace were affected by the events that unfolded.

MONEY MARKETS

The asset class hit the hardest through indirect exposure from the fallout was the money market sector. If there is a sector or investor that has felt the brunt of the volatility over recent years, it is the short-term investor. There is no doubt that the landscape has changed, and there is a high probability that the scenery will continue to change in the near future. The best way to look at all the change within the sector is through the regulators' eyes. For years to come, the money market sector will continue to evolve, with strength accomplished by creating a solid foundation through added regulation that will possibly change the industry's characteristics.

Money market securities have faced many challenges that continue to linger even four years after the initial malaise. Treasury bills, agency discount notes, commercial paper, time deposits, and repurchase agreements—better known as repos—constitute the lion's share of front-end money market securities. Investors that place money in a money market mutual fund are indirectly subject to these securities. The exposure doesn't end with fund investors. Corporate treasurers use this market and securities to run their daily cash management function. Institutional and retail investors are also subject to the ups and downs of the front-end securities through short-term separate account strategies. The recent environment has impacted all of these securities, some in positive ways and others, unfortunately, negatively.

Short-term anomalies always occur within markets, which is to be expected. For these anomalies to last for years is a tragedy, to say the least. Over the past four years, change has occurred. Change is usually driven by both technical and fundamental characteristics, and over time, the separation or differentiation between these two drivers has converged. The distinct line in the sand is not so distinct anymore, and the water is muddied. In the wake of the financial crisis, in addition to the primary sectors, subsectors of the money market arena were changed forever. For example, asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) was once a staple in so many money funds and strategies. ABCP helped diversify portfolios by providing new names to managers for purchase. These securities were eligible securities and conformed to the rules and regulations that governed money funds. Rightfully so, there were many programs that carried a solid track record prior to the downturn and to date, still have a solid track record deserving a spot in a money market fund. At the other end of the spectrum, there were tranches of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and other more esoteric securities even within the ABCP sector that made their way into money market portfolios. The ability for them to find their way into the portfolio was beyond me and primarily driven by the triple-A rating and enhanced yield that they carried. Many of these securities were overcollateralized with underlying assets, which helped to enhance the securities' characteristics and attractiveness. What this meant was that if circumstances precluded the money borrowed from investors from being repaid, the underlying securities or assets would then be distributed or sold and the cash distributed to investors. Securities structured with the overcollateralized feature were supposed to bring comfort to the asset manager, and ultimately, the end investor. In a normal environment they might have; that is, until they were tested and all parties involved realized that in the middle of a meltdown, the process is not always as smooth as it may sound. In a normal environment, liquidity is not a problem within most sectors, including those within the front end. When the markets showed signs of imploding, though, liquidity was tested. Unfortunately, the tradability of the front end was severely impacted and liquidity dried up very fast. Portfolio managers shunned ABCP specifically, and the securities prices fell. The downward price movement was accompanied by a sharp fall in supply. This was expected, as many of the issuers of these securities were also the large financial institutions that were fighting the battle with their balance sheets due to downgrades and mark-to-market issues. The price action makes sense. Why would an investor want to lend money to a security owned or sponsored by an ailing bank? The sponsor or financial institution providing support to the security was already in the limelight, as investors were frantically trying to calculate which institution might be next to close its doors. In addition, investors and analysts were attempting to decipher which program sponsor had a rescue plan to save its ABCP program. Confidence continued to erode and remained an issue for some financial institutions. In the time of crisis, many found it very difficult to receive funding, even with a strong balance sheet.

When all was said and done, some of the sponsors stood behind the troubled programs, pumping money into them to support their activity. Others looked the other way and decided to let them fail. Many of the sponsors, some of whom supported the programs, were European financial institutions. Unfortunately, there was not a respite for these European institutions. As the financial crisis in Europe escalated, some asset managers were once again deterred from reentering various sectors within the market, including ABCP.

After three years, supply remains less robust than in prior years. The ABCP market continues to feel pain. As hungry money flowed away from this sector, it went right into Treasury bills and industrial or nonfinancial commercial paper. This was a time when the return of principal was much more important than the return on principal. This concept still arises from time to time, whenever there is stress and strain in the marketplace. Nervous investors who held that view created a strong bid in the marketplace for nonfinancial commercial paper and securities issued by the government. It took a very disciplined investor to hold true to his or her ideals and process and not be swayed by the enhanced yield available through investing in the financial or ABCP sector. The pickup in yield over nonfinancial or government paper was, at the time, in excess of 50 basis points. That might not sound like too much, but in such an ultralow-yielding environment and for paper with short maturities, such as one week or a month, that extra yield is enticing.

Discipline is another theme that will show up multiple times throughout this book. Discipline is the key to success and will test your process time after time and ultimately impact you or your portfolio.

TREASURY BILLS, THE FAVORED ASSET CLASS

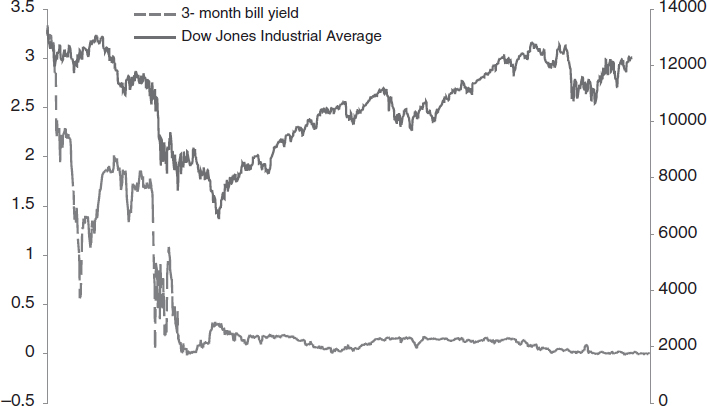

The Treasury sector, Treasury bills (T-bills) in particular, became the asset class du jour even with paltry yields close to zero. The demand for these securities—even with near-zero yields—outpaced agency discount notes, which have the implied support of the government. T-bills remained well-bid through the initial weeks, months, and quarters after the fallout. The risk on trade seemed to have left investors' playbooks. T-bills, which are viewed to be one of the safest investments due to the government backstop and short-term maturity, were again in the spotlight. As noted, this stardom within the different asset classes comes with a price, just like anything else. This time around, the glory was an increase in price, pushing yields to negative levels. If there were any doubts about this status, it was confirmed that, in uncertainty, investors tend to flock to the bill sector. It makes perfect sense that investors will sell risky assets when troubled times arise. This activity is the classic battle between risk appetite and a flight-to-quality trade in the purest form, pushing bills into near-zero and even uncharted negative territory. This flight-to-quality move did not just occur in the U.S. market: The move was much more widespread, touching markets worldwide. Globally, investors were at first looking to shield themselves from credit risk in all shapes and sizes. The risk–reward relationship makes sense. What is unusual is the shift that was witnessed as the equity market started to regain its footing. That is, the risk-on trade was back in full force in the equity markets and now combined with the risk-off trade in the fixed income market, fueling demand in the bill market. It does make sense to some extent that the equity market would regain its traction after the sharp decline in late 2008 and early 2009. Figure 3.1 shows the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the yield of the three-month T-bill from December 2007 through December 2011.

FIGURE 3.1 A unique time when risky assets and risk-free assets rally in tandem.

Source: Bloomberg data.

The initial move between both of the data points depicts the normal relationship. As the Dow Jones Industrial Average started its steep decline, the yield on the T-bill fell right along with it. There were two questions that everyone was asking: Is the equity market going to find support, or is it actually going to zero? If the markets are not going to zero, what will be the driving force and when will the tide turn? As we know, the equity markets did turn. The final days prior to the turning point, the tone within the markets was extremely negative. The 11-plus hour workdays felt like 20. This was one point in time that I would not have wanted to live a day in the life of an equity trader or portfolio manager. The sense of long hours might have been because there was no escaping the negativity. Once out of the office, on the ride home all you heard about were the problems and difficulties within the market. Comparisons on top of comparisons of prior recessions happened constantly. With every headline, there was risk that a credit we owned and held in a portfolio was next in line for the firing squad.

When the markets turned, it felt like a heavy weight was lifted off. But not so fast. The problem: The bill market didn't follow the expected course of action. The bill market should have started to move higher in yields as the battle was now overtaken by the risk-on mentality. Multiple factors have an influence on the short-term markets in which bills reside. This time, there were four reasons bill rates remained low and did not act in normal fashion as the equity market rallied:

- Central banks made accommodations.

- Global growth remained challenged.

- The global banking and financial institutions were in the process of deleveraging and firming up their balance sheets.

- Geopolitical concerns continued.

Figure 3.1 shows how the three-month bill remained well bid, almost flat-lining while the equity market marched higher. As a barometer, low T-bills and even Treasury securities are usually a sign that there are troubled times on the horizon. This time around was different, due to the Fed's ongoing efforts that artificially locked in rates at abnormally low levels. Post-crisis, the Fed has provided a quarterly view on when it believes interest rates will begin to rise. This move is geared to provide additional transparency into the market. This activity may continue to hold rates low unless the economic landscape starts to strengthen. The U.S. economy has strengthened since the equity market bottomed back in 2009. The sustainability of growth is what is in question and probably will be for years to come. Working against the positive growth trends in the United States are the headwinds from Europe and sovereign debt risks that just will not go away. Until these headwinds are removed from the picture, the dislocation is likely to persist. The bottom line: Ultralow T-bill levels are not always a sign of troubled times ahead. Granted, we are not in a perfect environment with steady global growth, low inflation, and a healthy labor market. If we were, my expectation would be that the bill market would be moving higher with the equity market. When that time does arrive, driven by less-accommodative Fed activity or stronger U.S. and global growth, the markets should revert back to the norm, removing the dislocation that has been plaguing front-end investors for the past three years and counting.

The contagion effect plagued investors in the midst of the crisis and is now part of everyday investing life. It makes complete sense that if an issuer of debt falls on hard times, the investor base will become nervous, pulling out of the name. In the fixed income world, hard times might mean a couple of different scenarios. A deteriorating balance sheet is never a good sign for a company. This would raise the possibility of a ratings action. Ratings actions within the fixed income world need to be viewed differently depending on the type of portfolio you are managing. For almost any strategy except a money market fund, negative ratings action could be a buying opportunity at a cheaper price, depending on the reason the action was taken. The spread usually will widen out or sometimes may even tighten even on a downgrade. This type of activity doesn't always occur, but it is known to occasionally happen. Here is a great example. If investors were expecting a multinotch downgrade—that is, more than one step lower—and the rating agency took action and only lowered the credit rating one step, investors would look at this as a victory. Depending on how much widening took place in anticipation of a downgrade prior to the event, spreads may now look attractive and buyers may step in. If you are managing a money market fund, it doesn't matter if the current or new levels accurately reflect the rating activity. Different regulations and guidelines do not permit lower-quality debt in the portfolio. Because lower-quality debt is not allowed, sellers will emerge or buyers will go on a strike with that particular name. What that means is that investors will not provide loans or fund the issuer at the current price levels, or at all. In the end, that would put downward pressure on prices, pushing yields higher. That is a textbook example of supply and demand. It is comparable to what happens to those issuers that are facing financial trouble. Worse, contagion may occur, pulling down companies that have stronger balance sheets with those that are under attack. Contagion could also take place by region, though not because of the obvious issues. The ongoing concern about a sovereign default occurring in the eurozone is a reality. There is one positive in this entire situation: the longer the European governments kick the can down the road, the more time all the financial institutions have to mitigate exposure. The bottom line is that these institutions are able to take the necessary measures to shore up their balance sheets and hedge exposure.

Two ways to accomplish this are by reducing exposure or by writing down the value of the debt they own. With that in mind, contagion has to be looked at another way. What really could bring any one of these companies down? The root of the problem is the lack of investor confidence. The fact that investors are losing confidence will likely create a drain on the company's cash reserves, which may impact and erode the balance sheet. We saw this the day Lehman shut its doors and subsequent days during the week. The equity market was falling, and falling swiftly. The financial sector was punished the most, taking the lion's share of the heavy hits. The part that I remember most vividly is that each day, the stock market—the investors within the market—would latch on to a new name and drive that price down. (The shorts would come out, that is, until the government placed a ban on that type of activity.) Anyway, the shorts would come out, and at times, seemed like they were trying to drive the company out of business. The downward trajectory of the financial institutions' stock price spooked many fixed income investors who already owned the debt of that company. If they didn't already hold a position, they were sure enough not going to put new money to work and invest in a company that was being targeted that day. It was an amazing time, but not in a positive way. Even overnight paper—that is, paper maturing in 24 hours—was not taken down. I was one of those individuals shying away from those names, and rightfully so. The risk was too high. The spiral effect was too real. Balance sheet concerns were not the issue. Markets were moving too fast and too furious. The usual balance sheet woes quickly turned into liquidity concerns, which have the ability to take down a company much faster than the deterioration of a balance sheet.

This is an ongoing theme in today's markets. The run on liquidity or an old-fashioned bank run is a concern today. For instance, if the debt crisis in Europe continues to intensify, financial institutions that have exposure are not likely to go under due to the exposure they have on their balance sheet of sovereign debt. If the entity falls on hard times, it will likely happen because of a run on the bank. The equity market will be falling, driving the stock price of that institution lower and lower. Next will come funding pressure, which is the inability to raise money at market levels. Following that will be signs that investors are removing the institution's name as an eligible investment. You will be able to tell this is happening by the issuing patterns. This is one gauge of how we assess if a company is in trouble. Throughout this entire process the rating agency may still have a top-tier rating on the name. How, you ask? Well, the aforementioned steps could happen so quickly the rating agency doesn't have time to react. The issuing or funding pattern may shift from receiving funding at the one-year point on the curve and slowly moving to shorter maturities. For example, if investors are not buying one-year paper, the company may attempt to issue six- month paper. If investors remain skittish, three months goes to one month, and so on until overnight funding is hard to come by. It is also important to monitor the funding points of an institution. This is accomplished by analyzing certain maturity points and comparing the yield offered that day with yields of the company's peers. For example, if the average for three-month bank commercial paper is 30 basis points but one particular company is paying 50 basis points, you can deduce with high certainty that the company is having trouble finding funding. In all honesty, fear drives markets, and in particular, the front end of the market. In today's environment, this fear turns into the ongoing fear of collapse.

The taxable market was not the only market that felt the wrath of the recession. The municipal market was also under pressure. Ratings were challenged, as were money market securities in the tax-exempt space. It was a challenging time, and without a road map and a disciplined approach, the safe and smooth ride was likely to run out.

MUNICIPALS FELT THE PAIN AS WELL

Municipal bonds are looked at as an asset class all to themselves. At times, this class trades with similar characteristics to the corporate market and other times the Treasury sector. Today, the municipal market has many more similarities to the corporate credit market than it ever did in the past. This is due to a few stark changes and developments within the markets in general over the past few years. Historically, municipal securities have been known for safety and low volatility. Investors were able to invest with confidence that the principal invested would be returned at maturity. Broadly speaking, one reason for this confidence was that states and municipalities are able to raise taxes and in some cases look to the government for funding if needed to fulfill obligations. Additionally, many municipal issues carried what was known as a wrapper. This is insurance from an outside agency to add stability and confidence within the market to investors. In some cases, the insurance wrapper helped the municipality attain a higher rating than it would have without the insurance. There were some instances where the insurance helped the issue receive a triple-A rating. One of the changes alluded to previously is that, in an effort to save money, the majority of municipalities have decided to forgo the insurance wrapper at this point. There are multiple reasons for this decision. For one, the economic climate has changed. Municipalities and states have implemented different austerity packages in order to shore up their fiscal position. As you can imagine, this is quite a daunting task at times. In addition, the fee to insure its debt was enough to curb the prior addiction. Investor appetite was also moving away from the need to have municipal debt wrapped. Driving this move was fallout from the market correction in 2008. Bond insurers over the years started straying away from what seemed to be their core business. Some of these insurers started insuring and taking positions in the structured credit markets. You can draw the conclusion about what happened next. When that market imploded, some of these insurers were hit with multiple claims that now pressured their balance sheets. As a result, their credit ratings were lowered and investors began to fear that the bond insurers that were originally created to provide a backstop to municipal losses were now more a liability than a benefit. This newly attained status as a liability could easily be seen through spread comparison and increased yield. Common sense would tell you that a triple-A insured bond should be more expensive to own with a tighter spread. The exact opposite occurred. Almost all bonds that had an insurance wrapper were treated like bonds on the edge of default. The municipality that issued the debt might have been rated single-A, or even double-A, without the insurance. With the insurance, the rating went to triple-A status, and the bond still traded as if it was a troubled credit. The stigma of being tied to an insurer was hard to shake. The market was very dislocated. Low single-A debt was trading better and richer than debt carrying a double-A underlying bond that, when wrapped, had a triple-A rating. What was once normal turned into what seemed like an episode of The Twilight Zone.

The removal of bond insurance is not going to create turmoil or disorderly activity within the broader market, but how it affects the front end of the investing community is a little bit of a different story. The short-term municipal sector is similar, with its counterpart within the taxable space. Low-volatility, high-quality names are what fund managers fight over. Short-term municipal debt, such as variable-rate demand obligations (VRDOs), is heavily utilized. These securities are issued with a feature that allows the holder to put back the debt at different stipulated dates. In essence, this “put” allows the investor to give back the debt to the issuer. This predetermined schedule may be in the form of daily, weekly, or monthly time horizons. These are just a few examples of the variable-rate demand obligation structure. These bonds are usually triple-A rated. Helping to attain the triple-A rating is the liquidity provider or financial institution that provides the letter of credit to the deal. The letter of credit is usually required because of the put feature. When markets are calm and free of negative headlines, the solvency, liquidity, and creditworthiness of a variable rate demand obligation is never questioned. The problem is that in today's environment, how often do we have a time period, or even a day, when there are no negative headlines or exogenous events taking place impacting investor sentiment? The other problem: Many of the banks providing support through a letter of credit or otherwise are European financial institutions. This concern has grown over the course of the past two years, as the European debt crisis has yet to recede. Some of the institutions providing the letters of credit to the municipal market also find themselves in the middle of the European crisis. The skeptical side of me says that the current situation is starting to carry similarities to the insured market prior to its implosion. The fact that certain European banks have a hand in providing a letter of credit to U.S. municipalities seems a bit out of place. Is the stage set for collapse? Maybe not, but why take the risk? Why introduce a problem that is halfway across the world into a market that is centered within the United States and is a completely different market? European institutions are not the only players; there are other institutions that provide a backstop within the municipal sector. The municipal world is not the place to have European exposure. Why not diversify this risk away? From an investment manager's perspective, it may require them to execute another trade or two. That, however, is their job. By diversifying away this risk, the portfolio manager may also need to give up a couple of basis points in yield—a penalty, if you can call it that, that is worth taking. There are some who might disagree with my view; as history proves, there have not been too many problems within these securities and sector. Though that may be, we have not had to navigate through the type of events that investors have faced over the past few years. In the end, this is not a risk that I am comfortable having.

AUCTION-RATE MARKETS WERE HIT HARD

Before moving on, it is necessary to touch on the liquidity event that took place in late 2007 and 2008 within the auction-rate preferred markets. There is sometimes confusion about the auction-rate and variable-rate demand obligations. From an investor standpoint, the primary difference is that the variable-rate demand obligation has a built-in put feature, as previously described. The put feature is controlled by the investor. They have control. This is a key difference between the VRDOs and auction-rate securities (ARSs). In ARSs, the investor lacks this benefit. The issuer drives the callable feature. If the issuer is not interested in purchasing the security back, it goes through what is called a Dutch auction process, administered by the dealer community. Prior to 2007, the auction-rate market was functioning. I remember having multiple conversations with different dealers about these securities and why I should purchase ARSs from them. They always affirmed that they (the dealer) would step up and buy the security if the auction failed. It sounded great; however, I am not a fool, and when push came to shove I knew that the broker-dealer would be looking out for only one person, and that was not me. Happily, I was not a buyer, and when 2007 hit and the liquidity crunch in the ARS market was in full force, I was smiling. Securities that were trading one day at 2 percent skyrocketed to 10 percent, and in some cases, higher. There were no buyers to be found. The issuer didn't have the necessary funds to repurchase the debt; the dealer community was starting to have balance sheet issues and didn't want to add another illiquid security to its books. With all the options unsuccessfully used and no letter of credit like the VRDOs have, there was no choice other than falling prices and rising yields. Now, if you were a holder of the debt, at the reset date, you were capturing a significantly higher yield than a few days or weeks ago. The problem: There was no liquidity. If you were needed to access your funds, you couldn't; you were stuck. I took a lot of flak for my skeptical view, but in the end, remaining disciplined paid off. I have never been a fan of these securities. I guess it can be said I have control issues, and not having control over the ability to put the bond back to the issuer was a deal breaker.