21. Power to the People: Participant-Driven Health Research at Genomera

Technology entrepreneur Greg Biggers is a problem-seeker. In 2008, he came across personal genetics when he listened to Hugh Reinhoff, a medical geneticist and founder of MyDaughtersDNA.org, spell out his lifetime challenge and took participant-driven health research using personal genomics as his own challenge. Reinhoff had set up a laboratory in his attic equipped with second-hand DNA analysis equipment in order to figure out the genetic basis of his daughter’s undiagnosed syndrome. Deeply touched by Reinhoff’s painstaking and inspiring effort, Biggers realized that analysis of DNA and health data was no longer the exclusive realm of scientists. He also realized that health-related issues were incredibly personal, that deeply touched people’s lives. So, he left his job in a software company, raised seed funding, and started Genomera with a small group of software developers and an expert advisory board. By founding Genomera, Biggers embarked on an ambitious journey to change health research.

Genomera is a company doing participant-driven health science research that combines personal health experiments, scientific evidence, and social networking. Described as “health meets Internet and social software” to “heal the world,” Genomera explores the intersection of health literacy and citizen science. Does daily meditation or relaxation practices reduce average blood pressure? How does the vitamin D intake affect sleep? These are research questions that initiated scientific protocols at Genomera. Many people are concerned with health issues that might not be interesting for a research laboratory, from scientific and economic point of views, because they are either too mundane or too rare.

In order to address these concerns and interests, Genomera developed a platform for research that is intuitive but rigorous enough to support sophisticated research and rigorous and scalable health science studies. In its online platform for health science, supported by cloud-based software, participants can design and implement scientific studies themselves. The service reaches out to two emerging areas in health research. On the one hand, the company provides a platform for citizen science research that caters to the quantified self and personalized medicine communities that design and carry out experiments by and on themselves. These are trying to answer questions such as, how does magnesium affect my sleep and how does my genomic profile moderate this relationship? On the other hand, the service draws on a trend of crowdsourced clinical trials, providing a way of recruiting trial participants with available personal genomic data who are willing to contribute to research.

This health research platform is participant-driven, bears no hierarchical structures and is enhanced by a social networking component that supports research protocols and discussion of findings. Many members of Genomera have profiled their personal genome and shared it in the platform for research purposes. Therefore, the pool of members with genomic data is a considerably valuable asset for Genomera, which can use it to market its platform as a service to larger pharmaceutical companies.

Joining Biggers at the very early stage of Genomera were other two experimenters in personal health research; Raymond MacCauley, formerly at biotech firm Illumina, and Melanie Swan, founder of DIYgenomics, had been developing Quantified Self experiments and knew Biggers from health-hacking meetups, whom they told they were eager to create a platform to support data collection in those studies. Biggers had begun developing Genomera and they joined the company. In 2011, the seed funding accelerator RockHealth, specialized in health start-ups, funded Genomera with $20,000. The company proposes an innovative business model for clinical trials and health research, based on personal health collaboration, which is radically different from the current paradigm in pharmaceuticals.

How Does Genomera’s Research Platform Work?

Genomera is functioning in private beta mode, which means that the platform is under development and interested people are required to ask for an invitation to become member. Any member interested in a particular health-related problem can propose an experiment. Initially, most study proponents were people who actually suffered from a health condition, or people who related to these problems through a personal relationship. Then, other members will help to formulate testable hypotheses and to design a research protocol in order to create a scientific experiment that will be carried out by the members of the community.

People who participate in the study as data participants perform the protocol on themselves and share their data with the group for joint analysis. A myriad of online tools and low-cost genomic tests, accessible today, enable participants to collect a large amount of data about how their body is behaving during the experimental period. After data collection, people enrolled as discussion participants collaborate online to produce results and discuss findings.

By facilitating health research carried out by “lay scientists,” Genomera is part of an emerging movement for citizen science. In July 2014, there were around 18 public studies in progress and 15 in the design stage. Using Genomera’s platform for health studies, as an organizer or as a participant, is free of charge. Revenues are expected to come from sponsorship and from services provided to other companies or organizations, such as test referrals and advanced analytic services.

WOW: Participant-Driven Health Research

Say people start with an interest in, for instance, how nutrition affects sleep or how their diet is appropriate for their genomic profile. By working together with easy access to data collection tools, reaching findings and gaining insights is faster and cheaper than in research laboratories. MacCauley believes that this kind of citizen science is fueled by a personal appeal motivated by a self-interest in one’s own health and the possibility of generating immediately actionable information. Eventually, participants running the study can obtain results that are important for science and health practice.

“We want to give any individual a voice in health sciences and let them influence or actually set the agenda, so they can use evidence-based science to find answers to the questions that matter most to them.”

—Greg Biggers interviewed for digital agency Possible in 2013

One study, Butter Mind, intended to analyze the effect of butter consumption on cognitive skills. It was inspired by a university professor who was intrigued by an intuitive perception that eating butter everyday improved his reasoning. Genomera ran a study lasting for 21 days and engaging 45 people who ate a daily dose of either butter, coconut oil, or none of these, and performed also daily math quizzes. Thus far, there were two different studies following up on the results of Butter Mind.

“Since the first study we helped orchestrate [on vitamin B metabolism], we have proven two important items. That participant-driven research is credible and productive, and that Internet study operations bring efficiency and scale to the world of health research.”

—Greg Biggers interviewed for Nature in 2012

Early studies, such as Butter Mind, contributed to developing Genomera’s platform by providing data to improve collaboration process, data collection, participant engagement, and results. Despite acknowledging that these earlier studies have worked as a proof of concept, the company has not disclosed details regarding how the platform introduces scalability in health research or how it is a credible alternative to current clinical trial methods.

For Biggers, a novel health research model, that is more participative and democratic, requires that people are able to develop new roles in science making structures. Science projects at Genomera do not follow hierarchical structures. Everyone involved is a collaborator, either as an organizer or as a participant. Participants can take part in data collection as well as in the discussion of results. Moreover, almost everything in participant-driven studies is openly accessible, including design, participants, results, and unidentified data.

This way of doing science is utterly different from the modus operandi of public and private research laboratories, bearing more resemblance with garage laboratories and hackerspaces. Daring to propose a radically different model for doing health research is risky for the research process. Genomera needs to address concerns regarding results bias, random assignment, and experiment control, which are brought about by a model in which scientists who formulate research questions and design study protocols are also participants in those studies. These are challenges that Genomera faces when positioning its health research model as an alternative to conventional health research beyond genome-centered studies and opening up space for participant-driven science.

In addition to this, Genomera seeks to take advantage of how people behave socially regarding health issues and to boost that in favor of health discovery. The company’s insight is that participant-driven health research can be enhanced by the fact that people in their daily lives gossip and exchange information about how they deal with health issues, and what works for them and what does not. For instance, many people are self-medicated, others advise their acquaintances or their online readers about health and nutrition matters. A more productive and systematic approach to information exchange for health studies was put in place by PatientsLikeMe, a research network for patients with chronic diseases to share experiences and learn from others with the goal of improving well-being in the face of enduring medical treatment. Meanwhile, at PatientsLikeMe, patients generate data about their condition in everyday life settings, which can be used by researchers, organizations, and regulators to improve products and services.

Users of Genomera are not necessarily suffering from a disease; they can be interested merely in how their body reacts to different physiological and environmental conditions. They create individual profiles, upload personal data, including genomic and phenotypic data, follow research protocols, and track data over time. They also comment on their personal experience throughout the studies and discuss various issues related to the condition or effect being researched. By integrating a social networking component, the company provides a space of communication and interaction, which attracts people into becoming members of the community, in addition to a structure for systematic research.

SO WHAT: Cost Compression in Health Research

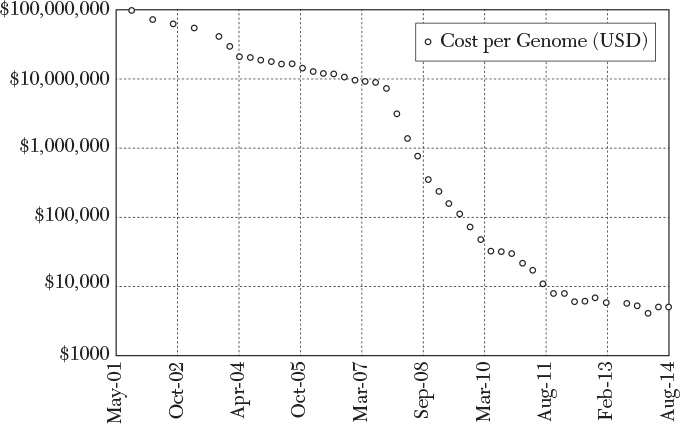

Research conducted through Genomera is largely facilitated by the plunging marginal costs of DNA sequencing (see Figure 21.1). Nowadays it is cheaper and faster to gather more data on human genomic profiles, largely due to the plummeting costs of human genome sequencing, the culmination of a decade long, large-scale public and private effort to reduce the cost of DNA sequencing which was previously around $1 billion.

Figure 21.1 Falling DNA sequencing costs1

1Wetterstrand KA. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). Available at: www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts. Accessed April 16, 2015.

Thanks to personal genomic services, the cost of ordering a DNA test and receiving personal genomic data in digital form has decreased dramatically in recent years. For instance, 23andMe offers personal DNA tests for about $99. Despite the radical cost reduction, in clinical trials and health research, the combination of genomic data with health records is scarce, even though it would help understand the incidence of diseases and the effectiveness of therapeutics at the individual level. An individual-oriented medical research would allow physicians to make personal recommendations and design individual therapeutics instead of prescribing drugs that are effective for the average population but often fail to provide effective results in specific cases.

Researchers affiliated with public and private institutions can launch studies and recruit participants from Genomera’s pool of members for academic and commercial studies. A recent study under development, initiated by DIYgenomics and the Center of Cognitive Neurorehabilitation of Geneva University Hospital in Switzerland, examined dopamine genes and rapid reality adaptation in thinking. It is based on ongoing research carried out the University, which aims to determine whether “genetic variants related to dopamine processing in the brain impact the processing of memories according to their relation with ongoing reality—in healthy volunteers.” The study involves 85 data participants and 17 discussion participants. The protocol required that participants confirm absence of neurologic disorders, submit personal genetic data, provide background demographic data, and complete memory filtering tasks throughout the study period. Since it will be used by Genomera to learn about collaborating with a university and a hospital, some of the data is also made available to academic research.

By integrating the personal genomic data of participants in its data collection protocols, Genomera designed a research platform that enables clustering the findings according to particular genetic profiles and drawing conclusions that support personalized medicine. This facilitates collaboration with research laboratories and companies, which is advantageous in the recruitment of research participants. Besides having an automated genotype-phenotype recruiting tool, Genomera developed capabilities to mobilize community members around a study, orchestrate protocol tasks, and collect data in digital format in a cost-efficient way.

How Genomera Is Different from Incumbents

Traditional clinical studies are expensive and time-consuming, which results in slow-paced drug development and medical breakthrough. Genomera proposed to break open the bottleneck of clinical trials that constricts the flow of research. In addition, its premise is that it only takes an enough number of people willing to follow a study protocol that can address a problem of their interest. The company is trying to prove that rigorous research can be carried out by a distributed pool of members forming an online community, outside laboratories, yielding useful results.

“In some ways, we want to be to health studies what something like WordPress or Tumblr is to a blog. We’re the infrastructure that makes it possible, but the actual work is because the people are doing it.”

—Greg Biggers interviewed for digital agency Possible in 2013

An alternative model of crowdsourced clinical trials is the platform created by Transparency Life Sciences (TLS), launched in 2012, which intends to cut clinical trial costs in half by opening the protocol design process to patients, physicians, researchers, and other stakeholders. The company created a Protocol Builder, which is patient-centered, is comprised of an extensive list of questions targeted at particular drug development programs which focus on drugs for chronic diseases. According to TLS, the goal is to rescue pharma compounds, which were shelved because moving them along the pipeline was too costly, and develop those using ideas from the crowd of patients, patient advocacy groups, physicians associations, and professional groups.

Crowdsourcing methods have called the attention of big pharmaceutical companies that also seek to lower the costs and increase the speed of clinical trials. In 2012, Pfizer terminated a pilot social media recruitment process for a clinical trial of an overactive bladder drug that took place in 10 states in the United States for 1 year. Pfizer’s “clinical-trial-in-a-box” expected that participants recruited through social media platforms would carry out the research protocol at home and report results using personal computers and mobile devices.

Eventually, recruitment was deemed very challenging and did not meet the expectations that Pfizer held. The online recruitment carried out in digital patient communities and typical web advertising channels failed to draw a sufficient number of participants. Moreover, the company explained that it was trying to do many different new things at the same time, since the trial included online recruitment, at-home study drug delivery, mobile- and web-based data reporting, online identity verification, and centralized investigator site. The organizers concluded that the recruitment strategy should be improved toward being more tailored to virtual trials and that the support and engagement of trusted healthcare providers could be important.

Contrary to Genomera’s research platform, Pfizer’s crowdsourced version of clinical trial focused on lowering costs by using online recruitment and allowing participants to perform tasks locally and report remotely. Genomera hosts health studies that are participant-driven, which encompasses a deeper level of engagement from participants, increasing the chances of success.

The company developed an intuitive and friendly system that makes people enthusiastic about what scientist do—formulating questions and looking for answers—and makes them feel comfortable with conducting research on themselves. On the one hand, people armed with their own genetic data are able to carry out simple research protocols, generate data in their real-world setting, and analyze results by comparing them against different genomic profiles. This creates knowledge about each person’s responses to physiological and environmental conditions, and to medical substances, enabling the creation of individual therapeutic profiles.

On the other hand, allowing people to organize studies and ask for specialized support to pursue a research question increases the pipeline of new ideas and questions. This could unleash new flows of discovery with a much lower cost compared to research carried out in research laboratories and companies. At this point, Genomera comes closer to a citizen science platform for massive health research. Unlimited study capacity could be generated as people become organizers and investigators in health science studies instead of subjects or participants of trials. Furthermore, a participative model for health research, combined with opportunities emerging from lower technology costs and wider access to testing services, reduces greatly the costs of research.

Genomera claims that, in a participative model, clinical studies will move toward people becoming shareholders of the benefits of research. Yet, the possibility of participants reaping the rewards of research triggers interesting questions concerning the contrast of Genomera’s model with the conventional pharma research model. Would participants be co-authors of published scientific outputs? Would they be owners of the intellectual property generated in the research project? The way Genomera evolves in the future may show whether participant-driven health research has the potential for radically redistributing the benefits of research to participant stakeholders, including intellectual property, authorship and patents, and blurring the boundaries between subject and object in research.

Finally, a participant-driven model generates engagement and attracts resources for health problems that are important for a minority of the population with rare diseases or for people in regions of the globe with very little resources. As it is designed, Genomera’s research platform may fill the gap of research on therapeutics and health conditions that are not economically attractive to big pharmaceutical companies, or simply are not a priority for organizations with scarce resources.

Challenges

One of the most salient challenges for Genomera is building trust within the group of potential research participants and within the scientific community. Firstly, getting more people involved, as organizers of studies and as participants, is critical in growing a community of “lay scientists” that is one of the most important assets of Genomera’s business model. Secondly, the company tries to build legitimacy and credibility among scientists, not only to validate their operations but also to generate business opportunities. In 2012, Biggers reported that the “goal of a prospective, longitudinal study that can yield scientifically valid results has almost been achieved” but no further details were released. In addition, Biggers spoke on behalf of Genomera at the U.S. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues about the company’s business model and platform, and how lay people designed and carried out research protocols, but also conducted analyses and collaborated with academics. Ultimately, Genomera aims to generate useful, rigorous clinical studies that may be published in scientific journals.

Outlook

It all started with a group of health hackers wondering how butter increases the brain’s ability to focus, and evolved to founder Greg Biggers addressing a U.S. Presidential Commission with a speech on personal genomics and citizen science. Biggers himself acknowledged that, at first at Genomera, they thought the scientific community would think they were insane for being serious about citizen-driven health research, even feel threatened. When Nature Medicine got captivated by their story, Biggers tried to persuade them from not reporting it, as he expected hostility, but when the story came out he came across a rather empathetic reaction from many scientists. Genomera was trying to make a difference in people’s lives and it was just what they had dreamt about when they became scientists. Genomera offers to heal the world by laying out the playground for curious, engaged minds to do health research together, from the mundane to the outstanding kind. It wants to make health research as a no-brainer as finding out how a spoon of butter in the morning can improve our math skills in the afternoon.

Genomera’s participatory research model is poised to flourish at the intersection of various mounting trends: citizen science, quantified self, personalized medicine, crowdsourcing in health research, and open innovation in drug development. Its platform for participant-driven health research has pushed down the barriers for doing sophisticated health research by lowering costs and by making it accessible to an increasing number of people.

From the Perspective of Dr. Markus Paukku, a Study Participant

The Genomera website only hinted at what exactly was happening on the social platform. The website modestly stated, “We’re crowdsourcing health discovery by helping anyone create group health studies.” A quote from a futurist stated that this was the “Facebook of science.” The site also had a picture of the CEO of Genomera testifying to the U.S. Presidential Commission on Bioethics. I joined the fray and signed up for the private beta.

Genomera had received some media coverage in Wired, Fast Company and similar outlets heavily slanted to all things technologically novel, start-ups, and Silicon Valley. Genomera is seeking to overcome the bottleneck restricting health science discovery providing consumers demand evidence-based answers, speed and engagement while offering researchers the needed efficiency and scale, as well as cohorts and data. Billed as a platform where anyone can organize scientific trials “working together, sharing data, supporting one another, comparing with one another, achieving insight faster together”—I was curious what exactly this looked like.

The community of trials organizers and participants are engaged in various types of studies investigating everything from the effects of caffeine on sleep to do common variations in the MTHFR gene keep vitamin B-9 from working? The platform offers a wide range of studies—in design, in progress, in analysis, and an archive of instruments utilized in trials.

The high involvement of the participants had been reported in the media but was still surprising. While some studies only required minor changes in diet and behavior, such as eating butter while doing math exercises, many trials on Genomera had a higher threshold for participating. Genomera clearly had a community of dedicated citizen scientists with access to, and interest in sharing, personal medical data. The website made it very easy to upload personal genome raw data from commercial companies such as 23andMe, deCODEme, FTDNA, or Navigenics. At the time of writing the aforementioned vitamin B-9 study had 49 data participants each volunteering their genomic data and committing to blood tests measuring homocysteine levels. I found a relatively less involved study entitled, “Sleep: Magnesium’s effect on sleep quality” which only required daily supplements and the monitoring of sleep via survey.

Genomera offered a window into the world of consumers, citizen scientists, amateur geneticists, and those comfortable identifying with personal biological experimentation. The data-driven hacker mentality aimed to rapidly gain results and leverage the social platform to ask new questions, propose new research, and access scientific trials. The falling price of genome sequencing suggests that emerging community will continue to grow potentially renegotiating the traditional divide between the medical community and patient, scientist, and consumer.

As for the results of my magnesium study, I personally did not notice any effect. However, the idea behind the Genomera platform is to build a community that collects and aggregates data from all participants with the aim of teasing out hidden patterns. This data is available to all participating in the study. As for the overall results, at the time of this writing the study was still ongoing, over 2 years after the trial was initiated. While, from this single user’s perspective, albeit one without a reference point, the platform had not delivered medical insights “faster” it had created a place where one could ask and seek to answer questions “together.”