Chronic stress is bad for your health and performance, but if you want to get things done, a moderate amount helps you focus and perform at an optimum level. The ideal state is when you’re both engaged and productive.

It is detrimental to suffer from constant pressure and stress. However, an eight-year study of 30,000 American adults found that, while stress shortened lifespans, it did so only in the cases where the individuals had described stress as harmful to their health. People whose stress made them miserable were damaged by it, but people who were stressed—but not distressed—were able to survive it much better. What does this mean?

Recasting stress

The “misattribution of arousal” may provide an answer (see “Is it stress you’re feeling?”). Emotions produce physical sensations, but we experience similar sensations for a variety of emotions, and the feelings we experience can be easily confused. What for one person is painfully stressful can be, for another, exciting and challenging.

A study by Alison Wood Brooks published in 2014 in the Journal of Experimental Psychology showed that, instead of trying to remain calm in stressful situations, people perform better when they recast their stress as excitement instead. This can be achieved with positive self-talk (for example, saying “I’m excited!” out loud to yourself), and by viewing the situation as an opportunity rather than as a threat.

Hitting the sweet spot

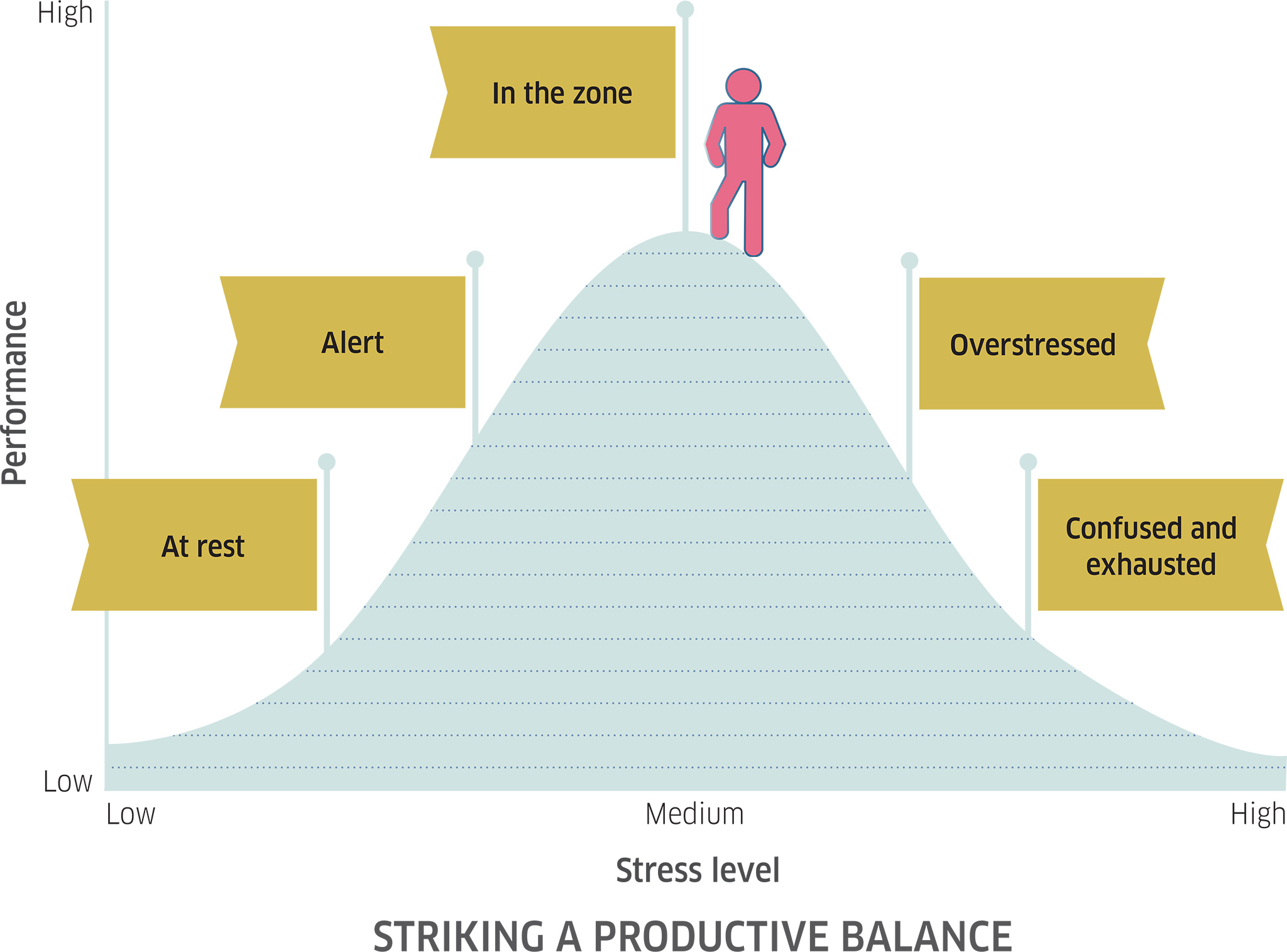

Some kinds of stress are just too much, no matter how positive your attitude. But exactly how much, according to what psychology calls “the Yerkes–Dodson law of arousal” (see “Optimum performance”,), varies from challenge to challenge:

- If you’re not stressed at all, you won’t be alert enough to perform well.

- If you’re under the right amount of pressure, you’re “in the zone,” performing at your peak.

- If you’re too stressed, your performance will start to suffer.

Instead of eliminating stress altogether, what you need to do is avoid excessive stress.

Preventing avoidable stress

How do we circumvent inordinate levels of stress? Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin recommends a “pre-mortem”: consider what might go wrong in any given situation, and prevent, minimize, or think about what you can ahead of time. Stress strains the hippocampus, the part of the brain associated with memory, which means you can become muddled. Levitin advises storing important information in places you can always access (such as digitally, or in “the cloud”) so you don’t have to rely solely on your memory. Anticipation won’t fix everything, but it can make a difference when you’re in a pressurized situation.

optimum performance

The Yerkes–Dodson law of arousal suggests that there’s an optimum stress level at which we perform at our best—when we are “in the zone” and functioning productively. As a general rule, purely physical activities call for higher levels of arousal, because stress sets our bodies to “fight or flight” mode—necessary for when we are, for instance, competing in a sprint race. For a purely intellectual activity, such as reading a book, our stress level would need to be on the low side to place us “in the zone.” The graph below shows the “zone” for an activity that combines physical and intellectual performance, such as an orienteering challenge. Here a medium level of stress sets us on the right track. When deciding how much stress is too much, think about what kind of task you’re undertaking and monitor your stress level accordingly.

is it stress you’re feeling?

is it stress you’re feeling?

An experiment performed in Canada in 1974 by psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron showed how we can misinterpret the sources of our stress. Male passersby who had walked over either a safe, steady bridge or a shaky bridge were approached by a female researcher on the other side, asked to fill out a questionnaire, and then given her number and told that they could call her if they had any questions. The men who’d walked across the less stable bridge were more likely to call the woman. Why? They’d noticed their trembling knees, rapid breathing, and butterfly-filled stomachs, but had attributed them to their attraction toward the woman, not the terrors of the bridge. This “misattribution of arousal” occurs when we misidentify the true source of our feelings. Make a habit of asking yourself whether what you are feeling is fear, stress, or excitement, so you can react appropriately as circumstances demand.