When it comes to taking a gamble, whether in a casino or on the stock market, many of us believe we’ll win. Knowing the psychological reasons behind this false assumption can help us on the road to success.

W e don’t always act in a rational way when we make decisions about what’s in our best interests. In fact, if we’re in a bad situation, we can often make it worse by pursuing an unpredictable course of action rather than simply accepting our losses and trying to prevent further damage.

The sunk cost fallacy

If we’ve invested in something that hasn’t repaid us—be it money in a failing venture, time in an unhappy relationship, or chips at the roulette wheel—we find it very difficult to walk away. This is the sunk cost fallacy. Our instinct is to continue investing money or time as we hope that our investment will prove to be worthwhile in the end. Giving up would mean acknowledging that we’ve wasted something we can’t get back, and that thought is so painful that we prefer to avoid it if we can.

The problem, of course, is that if something really is a bad bet, then staying with it simply increases the amount we lose. Rather than walk away from a bad five-year relationship, for example, we turn it into a bad 10-year relationship; rather than accept that we’ve lost a thousand dollars, we lay down another thousand and lose that too. In the end, by delaying the pain of admitting our problem, we only add to it. Sometimes we just have to cut our losses.

Prospect theory

Prospect theory

If a choice or product offers an uncertain reward, we are liable to evaluate it on its prospect rather than on its utility. This is to say that we tend to assess something’s value based on what it might be worth later rather than what it’s actually worth right now—and if that “might” is temptingly high, we’re more likely to make irrational decisions and invest too much in something whose utility isn’t worth what we give for it. It pays to be aware of possible future outcomes, but don’t let them rule you: a prospect is not a certainty.

The power of the near miss

A 2016 experiment for the Journal of Gambling Studies found that subjects who narrowly missed out on a win showed elevated heart rates and a greater desire to gamble again than if they lost by a large margin. Always remember that a narrow loss is still a loss, and take a deep breath before you act on it.

The Gambler’s Fallacy

The Gambler’s Fallacy

Do several losses in a row mean a win must be around the corner? Sadly not: this is the gambler’s fallacy, which assumes that the odds of an event happening next time are lowered by it having already just happened. For example, if you flip a coin six times and it lands on heads, what are the odds of it coming up tails? If you guess anything higher than 50–50, that’s the gambler’s fallacy. Evaluate each chance on its own probabilities.

Quantity versus odds

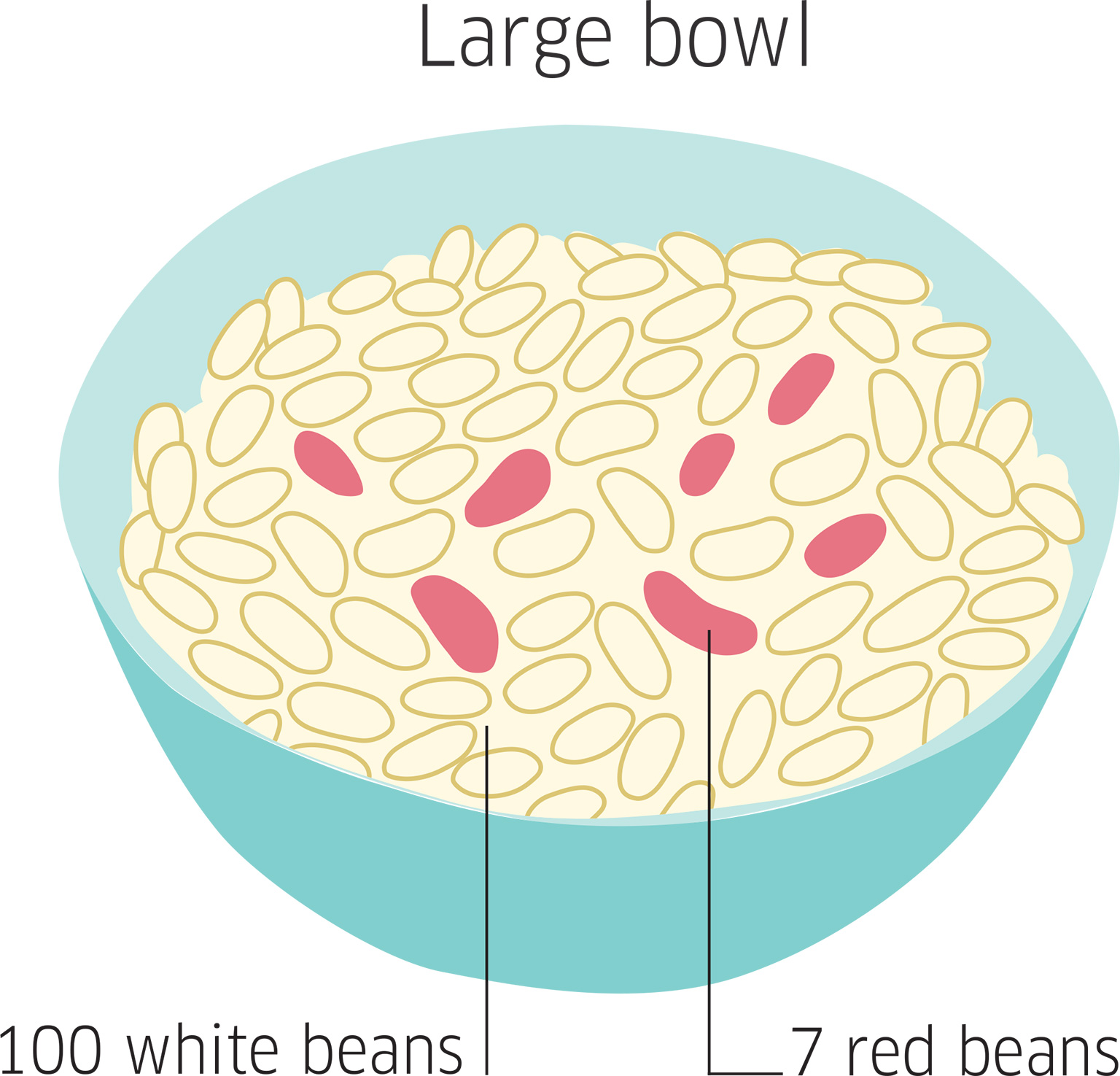

In 1994, psychologists Veronika Denes-Raj and Seymour Epstein offered US volunteers a chance to win a dollar if they could pick out a red jelly bean from a mixture of red and white jelly beans. Offered either a large, covered bowl with more red beans but worse odds, or a small, covered bowl with fewer red beans but better odds, most of the subjects—even though they knew the odds beforehand—chose the big bowl with the worse odds. The sizes of the bowls outweighed their rational judgment about which was the better bet. When making decisions, don’t let quantity blind you to the actual odds.

7%

Chance of Success

10%

Chance of Success

the Fallacy of composition

the Fallacy of composition

We can sometimes assume that the whole will be as good as each of its parts. Suppose, for example, you’re in charge of a startup, and you know that everyone you’ve brought on board is productive and efficient. It might seem logical to assume that, as a result, the startup will be productive and efficient, too—but this isn’t necessarily true. The fallacy of composition fails to allow for how the different “parts” interact with each other—if, for example, your efficient administrator and your highly skilled head of IT each assumes the other is in charge of collating prototype test results, then you have a problem. Equally, a unit composed of good people can still be working on a doomed project, and a project composed of good ideas may lack a stable center. When assembling a team with a common goal, always check the overall view as well as the individuals involved.