Memory is part of our ancient survival kit—but how do we make a Stone Age brain work for us today? Whether we’re trying to retain information or maintain our optimism, it helps to know how memory functions.

Why do we have the capacity to make and access memories? The most likely explanation is that this function evolved not so much to allow us to recall the past, but to inform us how to react in the present and attempt to predict the future. Knowing this can be useful to us as we look for ways to retain information, and it can also help us to manage our expectations.

Think about the context

Need to remember something? Studies show that our memory is adaptive—that is, it is hardwired to help us fit into our environment the best we can. A 2007 study (see “Survival instinct,”) found that we’re far more likely to remember ideas that we associate with survival, so if there is a piece of information that you have to remember, try picturing it in that context. Not to the extent that you panic yourself, of course—the scenario could be imaginary, or related to positive “survival” traits such as making allies or attracting potential partners.

Don’t discount the positive

Memory may help us survive, but it can also undermine us. Studies find that we’re highly prone to a fallacy known as “duration neglect,” and that this can lead to negative thinking.

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Jason Riis give the following example: a music lover listens with delight to a long symphony, only to be shocked in the final bars by the scratch of a damaged recording. The listener is likely to say that the experience was ruined, but in fact, only the memory has been spoiled—for more than an hour, the experience was very pleasant.

We tend to evaluate remembered experiences based on either their most dramatic moment or their ending—a phenomenon known as the “peak/end” rule. When motivating yourself, be aware that you may be liable to putting too much emphasis on bad moments purely because they were intense. Don’t let that intensity discourage you. A “failure” may have had months or years of success preceding it. Remember all the facts, not just the dramatic ones, and you’re likely to feel more confident.

survival instinct

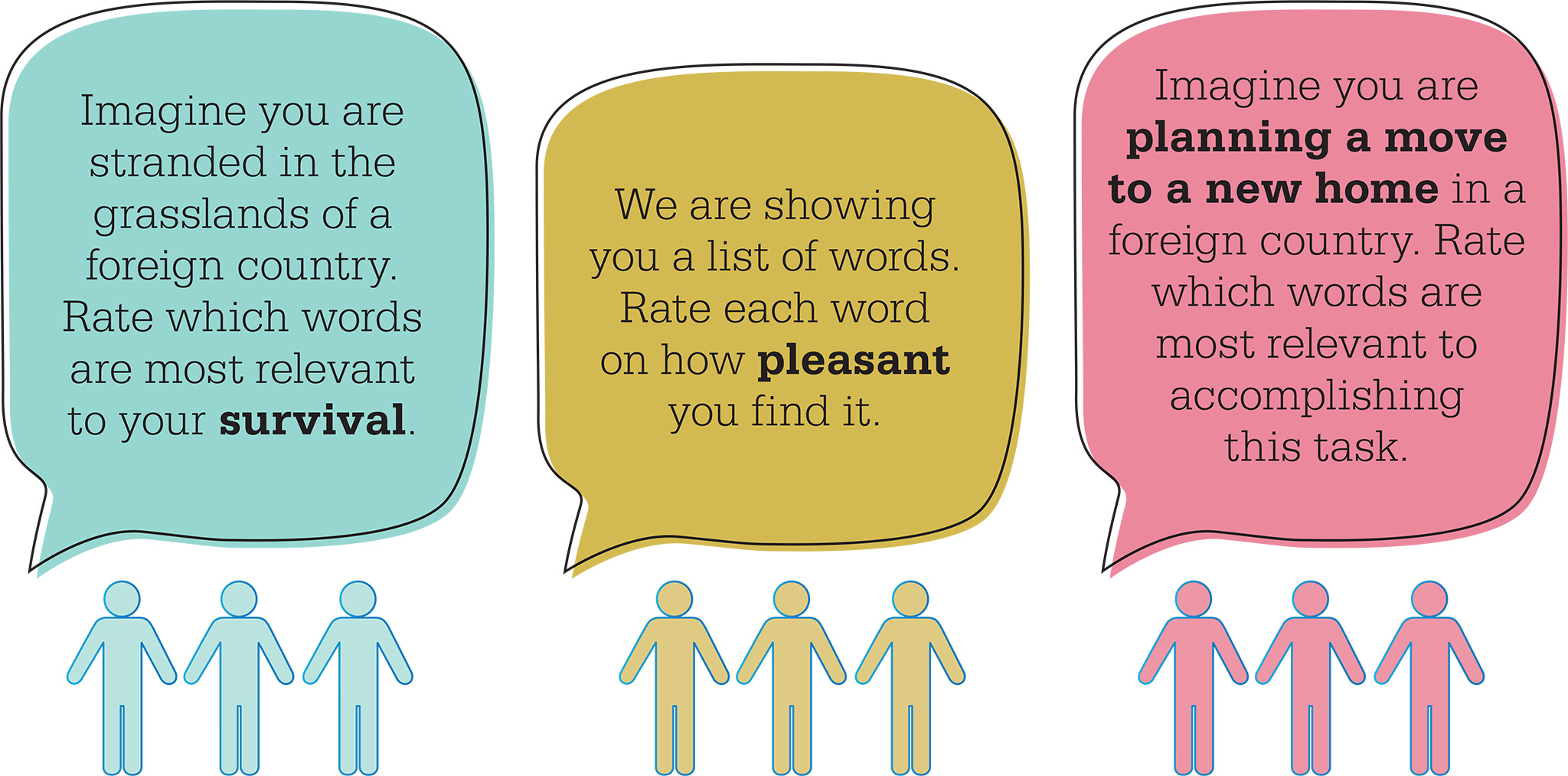

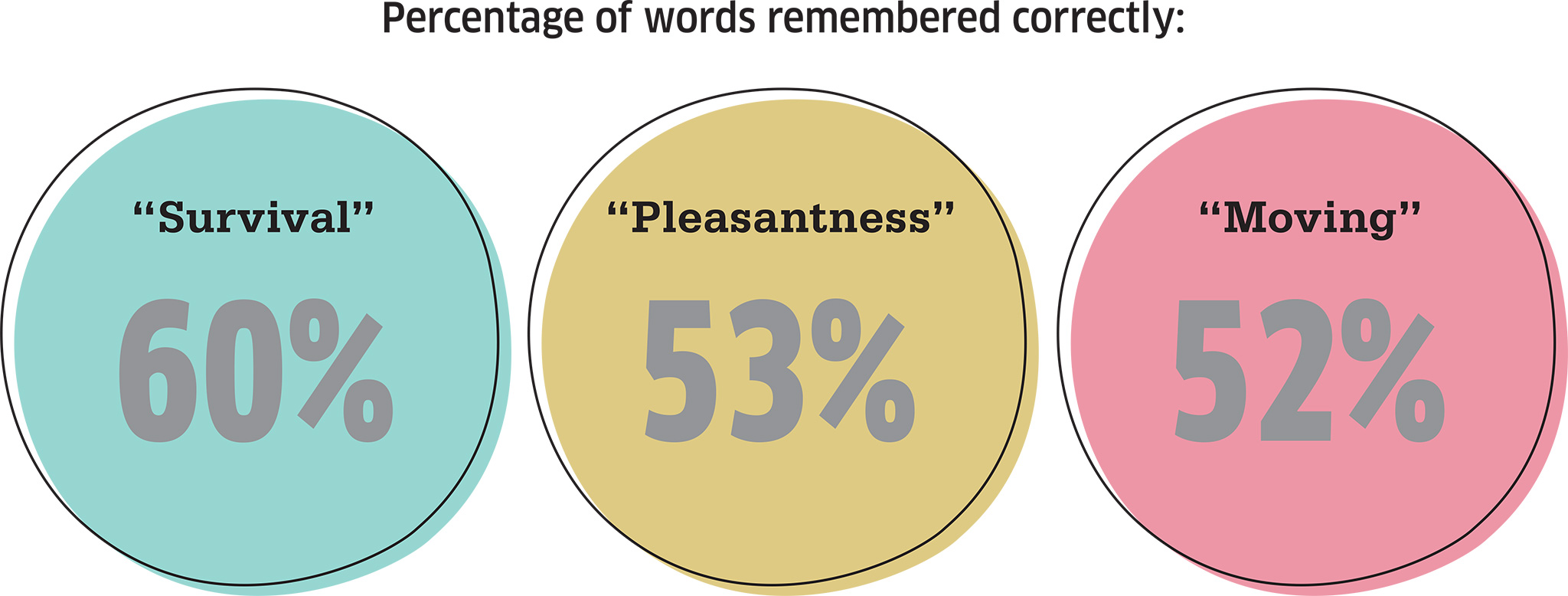

A 2007 international experiment asked three groups of volunteers to read lists of randomly selected words, such as “stone” and “chair." Each group was then asked a different question:

Even though the word list was the same for each group, the volunteers who were asked to think in terms of survival had the best recall. This is “adaptive” memory: we remember best what helps us adapt to—and survive in—our environment.

The Memory Palace

The Memory Palace

The ancient Greeks and Romans were master speechmakers, and they worked without notes. Their trick was to create a “memory palace,” in which they placed outlandish reminders in a familiar setting. You can try it yourself. Suppose you want to make a speech about growing the market for a product, an advertising campaign you developed in Canada, and your desire to test it out on social media. Picture this:

- You are outside your home. There is a huge plant on the doorstep, shooting up at great speed. (This reminds you of the word “grow.”)

- You enter your house. There is a dancing clown in the hallway with a maple leaf for a nose. (This looks like the leaf on the Canadian flag, which reminds you of the ad campaign.)

- You walk into your kitchen, but it’s full of tiny computers gossiping about your toaster. (That’s your reminder for “social media.”)

Classical rhetoricians remembered their speeches not word for word, but topic by topic. Contemporary science proves they were right to do so, because our visual-spatial memory is more powerful than our ability to retain verbal and numerical information. If you need to remember something, try creating your own memory palace, populated with outlandish cues.