Chapter 6

Developing a Proactive Grants System

THE MOST IMPORTANT single aspect of successful grantseeking is initiating contact with grantors early in the proposal-development process. Studies have shown a substantial increase in the success rates of grantees who make preproposal contact with potential grantors. By initiating the grantseeking process early, the proposal developer has the time to contact a grantor well before the deadline and the ability to modify his or her proposal based upon communication with the potential funder.

As the district grants administrator, your challenge is to encourage your grant-seekers to contact grantors and, while doing so, to create the impression that your district has a coordinated grants system. If several grantseekers from your school district contact the same grantor to present different grant ideas, it confuses the grantor and makes it appear as if your district has no priorities. Grantors do not feel that they should make decisions that will influence education in a school district without knowing the district's priorities. Because of this, many grantors (both public and private) will review only one proposal from the grantseekers' entire organization.

Your district's grant system needs to take the issue of access to potential grantors into account for three reasons:

- Preproposal contact means increased success.

- Uncontrolled access to grantors can result in the submittal of multiple proposals to one funding source and the loss of your district's credibility.

- An organized system of preproposal contact encourages grant-seekers to contact prospective funders, thus freeing up the district office's resources and the district grants staff's time.

In addition, your system should respond proactively and in a timely fashion to grantseekers who are investing their time and effort in developing proposals. They deserve to know what degree of support they will receive from the district grants office and what restrictions will be placed on their contact with grantors. Much of this can be addressed by requiring prospective grantseekers to receive district endorsements in advance. This advance endorsement or “sign-on” by district representatives avoids many problems.

Before getting involved in pursuing a funded proposal, the school district needs to know what types of funders their grantseekers are going to approach and what restrictions or rules the district will be subject to by accepting the funds, including those relative to the following:

- Matching funds or in-kind contributions of space

- Equipment purchase, ownership, maintenance, and inventory

- Release time for personnel—percentage of time and replacement for project workers

- Continuation of the project

A proposal sign-on system allows grantseekers to know where they stand relative to their district's priorities and mission before they invest their time and effort. Projects and proposals that address district priorities should receive more support from the district grants office as well as preference with respect to matching funds, space, and equipment.

Education is the key to instituting a mandatory grants sign-on system that is supported by your administration, teachers, other education professionals, and volunteers. All those involved in your grantseeking process must understand the need for a system that respects your proposal developers' time and effort, maximizes the limited resources of your school district, and maintains your district's credibility with grantors. This system can also alert others to the potential of putting interested groups together in consortia. The advance endorsement or “sign-on” system is extremely helpful to those required to prepare proposals as part of their job and find their time and effort are not fully appreciated.

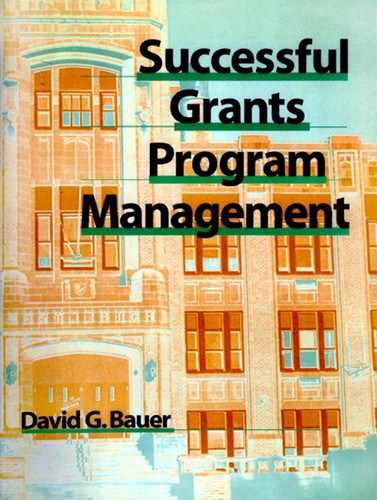

The first step is to have each of your grantseekers complete a School Grantseekers' Preproposal Endorsement Worksheet (Figure 6.1). Putting a sign-on system in place will allow you to track your grantseekers' progress. Assign a grants office identification and coding number to each preproposal endorsement worksheet and log that number in your database along with the grantseeker's name and school and the steps in proposal development that have been accomplished.

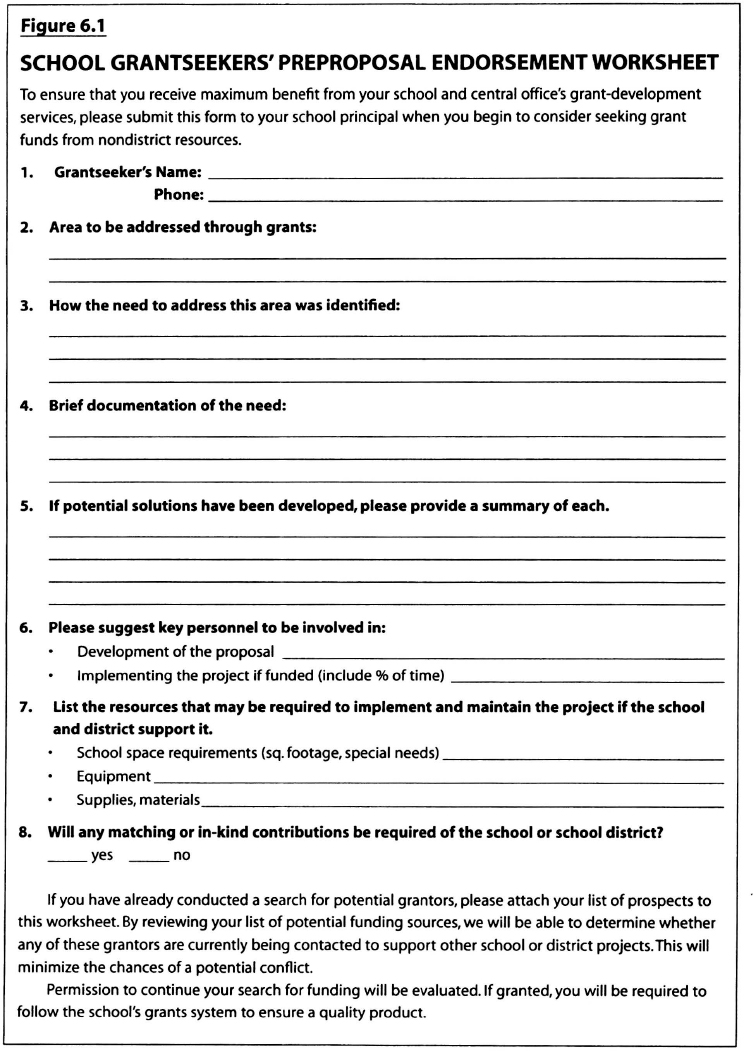

The Tracking Checklist (Figure 6.2) provides your office with a method for each project that is recorded and receives approval:

- District priority

- School/community priority

- Preproposal endorsement worksheet completed

- Preproposal endorsement worksheet returned with status (approved/rejected), signatures, conditions that must be met, and so on

- Search for grants carried out

- Search for linkages carried out

- Proposal being written

- Proposal undergoing review by quality circle

- Submittal process

- Proposal out for signature to __________

- Matching or in-kind contributions needed—amount, type, and funder restrictions

- Special services or assistance required from grants office

- Proposal status—awarded/rejected/pending

By implementing a sign-on system and tracking your grantseekers' proposals through development to submittal, you will be able to prepare a year-end report that includes the following:

- Number of proposal ideas developed

- Number of sign-on sheets returned and the status of each

- Number of proposals under development

- Number of proposals completing a quality review

- Status at year's end (submitted/rejected/awarded/pending)

- Matching funds (pending/awarded)

- Success rate total in dollars

It is difficult if not impossible to recreate this data at the end of the year without some type of sign-on procedure as part of your proactive grants system. In addition, your tracking system will help you see where your grants system is performing well and identify those areas that are not meeting your expectations. For example, if your tracking shows that many grantseekers languish in the proposal-writing stage of development, you can redirect some of the district grants office's resources toward helping them get over this hurdle.

Using Volunteers Effectively

Earlier chapters have encouraged the involvement of parents and other community members in brainstorming problem areas that grant funds could have an impact on and developing solutions to address them. Promoting this positive form of school/community involvement makes the volunteer a vital partner in the grants effort. This is truly what site-based management is all about.

Many theorists believe that positive action is based upon individuals setting their sights on solving problems and improving situations. Dennis Whately, author of Psychology of Winning, points out that individuals move in the direction of their dominant thoughts. By identifying solutions and developing positive ideas, your volunteers set in motion a system that moves toward completing the steps necessary to fund these ideas. Part of your role as district grants administrator is to educate and involve your volunteers to the point where they are committed enough to become involved in the most important stage of grantseeking—sharing their excitement and ideas with their friends in corporations, foundations, and government agencies.

The following sample letters and worksheets will help you encourage your school units to build an active volunteer component into their grants system by establishing grants advisory groups. Tailor these materials to your district grants plan.

Grants advisory groups can be set up by school units, departments, subject areas, or community. Individual advisory groups can then send a representative to a larger school district's grants advisory group that sets district priorities and deals with preproposal sign-on, endorsement, commitment of matching funds, and so on.

Worksheet for Planning a Grants Advisory Group

Use this worksheet (Figure 6.3) to help your schools develop a tentative list of the individuals whom they may want to participate in their grants advisory group. They should avoid placing well-intentioned zealots on the group. Although these outspoken individuals may be highly motivated, they can turn off the other group members as well as potential funders because they often lack the listening skills needed to grasp what the grantor is looking for. Encourage them instead to look for individuals who will make the grantseeking process less work for your office. Help them assess the skills and resources that each potential member will bring to the group.

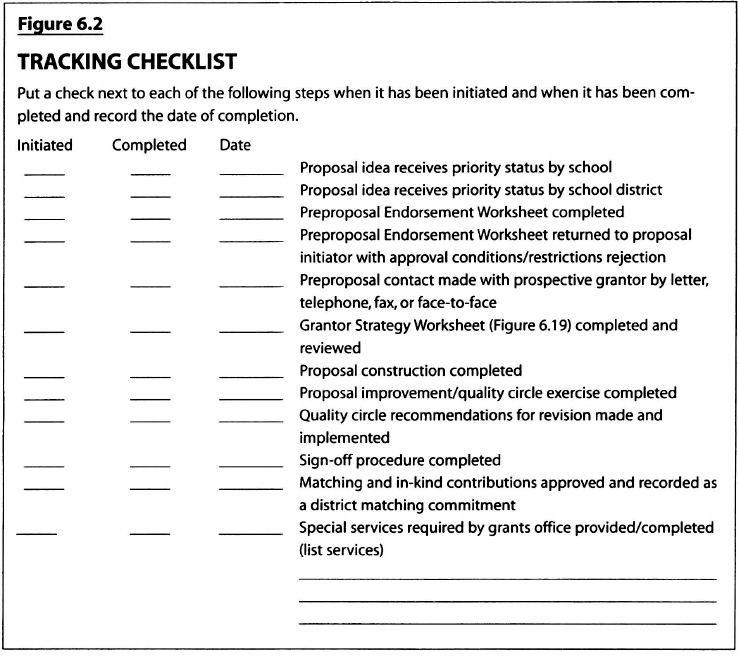

Grants Resources Inventory Worksheet

This worksheet (Figure 6.4) lists some of the resource areas that are helpful in grantseeking. The worksheet can be used in several ways. A quick review of the worksheet may trigger the names of potential grants advisory group members. Once they have been identified they can be asked to complete the inventory by noting their own skills and abilities and also listing the names of any other potential members next to the corresponding resource area. For example, if Sylvia Smith is filling out the inventory, she may indicate that she can provide sales skills. She might also indicate that an acquaintance of hers, Michael Doe, might be willing to provide computer programming services.

Once the group members have been selected, your school units should not be overly concerned with rules regarding their attendance at group meetings. If the member promises to provide the resources and skills needed, what difference does attendance make? For instance, salespeople who travel a lot may not spend much time in their offices or at home. It may be easy for them to make preproposal contact with a grantor in another part of the state or country but difficult for them to attend meetings.

To offer an example, a very productive sales executive on one of my grants advisory groups never attended a meeting but was instrumental in procuring several grant awards. When he was in a city with a potential grantor, I would e-mail or fax all the pertinent information to him at his hotel. This would include a description of the proposed project and information on the grantor, such as funding history or pattern. He would then set up an appointment with the grantor to discuss the project. After his meeting with the funding source he would e-mail or fax information back to me concerning the appropriate strategy to pursue in the proposal. He was highly successful at getting in to see federal and state grantors as well as foundation and corporate sources. In many cases, he was actually given preferential treatment over the grants and education professionals, who, after all, were paid to be there. My advisory group member was donating his time; he was actually being paid to be somewhere else. In reality, the preproposal visit was costing him money. Many grantors will respond favorably to such a committed volunteer.

Your advisory groups need members who are free to travel and who have skills or resources in marketing, budgeting, printing, computer programming, and so on. What could be more ideal than a finished proposal produced by a committee member donating his or her office and secretaries and having the budget checked by their finance department or certified public accountant?

Worksheet for Initiating a Grants Advisory Group

To complete this worksheet (Figure 6.5), discuss your plan to develop grants advisory groups with the faculty and staff in your district and ask them to suggest names of people they would be willing to contact and invite to take part in one of these groups. You may decide to form districtwide groups that focus on district priorities and problems, or you may form groups in each school. Either way, you will be amazed at how many excellent contacts they suggest. Don't be surprised if the spouse of one of your district's longtime volunteers or staff members is the marketing director of a local corporation and that he or she would be happy to donate resources, from graphics to preproposal contact, to your effort.

Sample Letter to Potential Committee Member

This letter (Figure 6.6) should be tailored to the individual and to the scope of the grants advisory group's work. For example, a small district may have one grants advisory group to assist in all grantseeking activities whereas a large district or one with diverse and critical areas of concern may have several, each focusing on one particular school or problem (such as illiteracy, delinquency, dropout prevention, drugs, alcohol, AIDS education, and so on).

The important point to get across in this letter and in phone conversations with potential group members is that they are not being asked for money. They are being asked to lend their brain power and resources to your grants effort. Grants are provided by foundations, corporations, and government agencies, and any help that advisory group members can give in setting up a meeting or even a telephone conversation with possible funding sources will increase your school's chances of success.

It is important that potential group members know that more than $90 billion will be given away by the federal government in 1999 and approximately $150 billion by private philanthropy and that they are being asked to help get some of that money for your school district. They should be reassured that they will not be involved in asking for a friend's personal donation but only in requesting foundation and corporate funds.

Remember, you and your individual school units establish the requirements for group membership. Individuals might ask how long they must serve. I suggest that you leave it up to them.

Webbing and Linkages

Point out to your district's grants advisory groups the dramatic increase in success that is possible when the prospective grantee makes contact with the potential grantor before the proposal becomes a finished product.

The corporate representatives on your district's grants advisory groups already know the value of linkages who can help them get a foot in the door with a client. The corporate world keeps track of who golfs, plays tennis, and vacations with whom. Being able to tap into this network is worth its weight in gold (that is, grant dollars). Because most corporate grants are funded because of a connection to the community, your district's grantseekers need to gather corporate inside information.

It is estimated that there are only about 3,000 full-time foundation employees working for 41,588 foundations, and only 1,000 foundations have an office, so the most logical way to make preproposal contact with foundations is through one of their 300,000-plus board members. The way to contact them is through a mutual friend or link. The same holds true for corporate executives and government grantors. The key is to educate your grants advisory groups about the importance of sharing their linkages. They must be assured that all information they share will be held in the strictest confidence. When one of your schools has an idea for a project suitable for a grantor that one of your volunteers can communicate with, your office will contact the volunteer to discuss the project and to ask for his or her help in setting up an appointment. The contact may be a simple phone call or a breakfast or lunch meeting to discuss the grantor's current interests and how they relate to your school district's project.

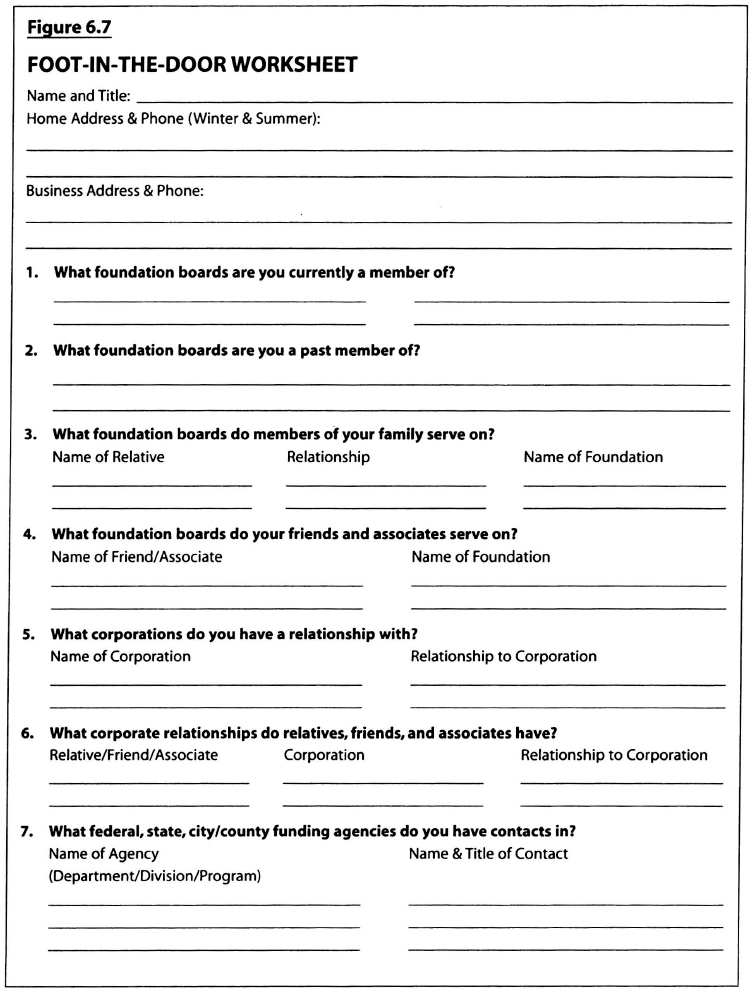

By being actively involved in your district, your volunteers will approach potential funders with attention-grabbers like “We at the _______ school district have developed several solutions to our problem with _______, and we would like to discuss them informally with you.” The grants advisory group members' depth of commitment and the detail with which they complete the Foot-in-the-Door Worksheet (Figure 6.7) also depend on their involvement in developing solutions and the degree to which they feel part of the solutions.

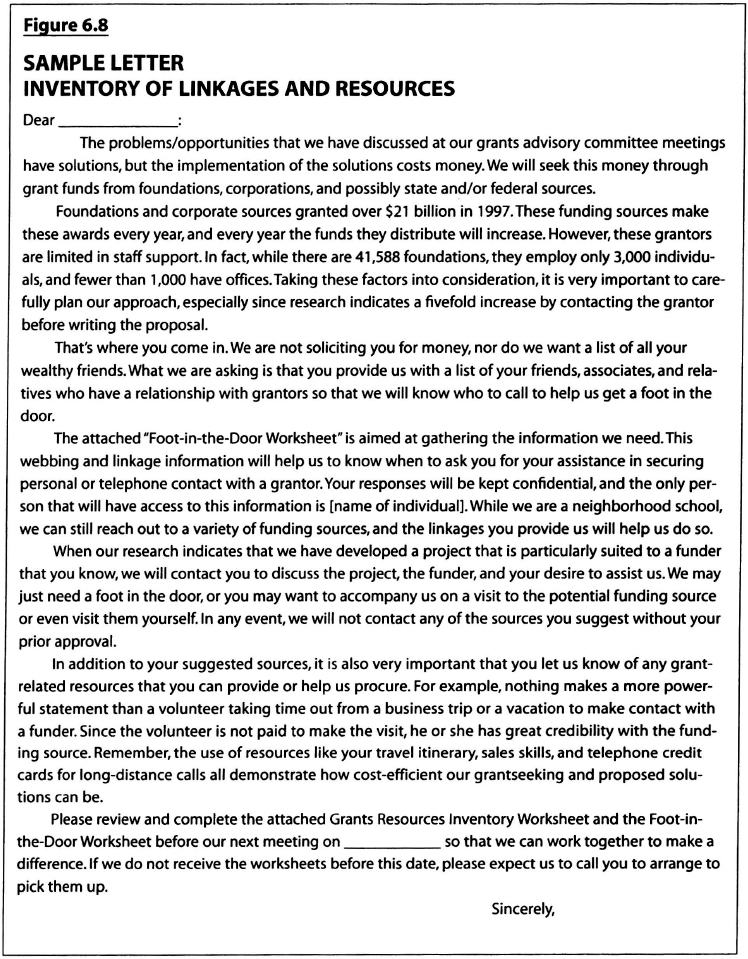

Sample Letter—Inventory of Linkages and Resources

The timing of this letter (Figure 6.8) is very important, and the quantity and quality of the linkages derived from it will most likely correspond to the prestige of the grants advisory group member who signs it. For that reason each group's most distinguished member should sign the letter and introduce the concept of linkages at the advisory group meeting. This will increase the likelihood that inventories and worksheets will be completed and returned.

The sample letter (Figure 6.8) and the Foot-in-the-Door Worksheet (Figure 6.7) are self-explanatory. The questions on the worksheet deal with types of funding sources. The volunteers can add any other information they feel would be helpful.

Someone might ask about the appropriateness of giving the Foot-in-the-Door Worksheet to your school district staff. I suggest that you explain the concept to staff at meetings and ask them to voluntarily share their links with the appropriate grants advisory group (school, department, and so on).

My clients who have organized and utilized their linkages have dramatically changed their grantseeking strategies. One organization I work with has decided to concentrate on those foundations and corporations to which they now know they have a linkage. The organization matches grantor interests with organizational needs and projects, and by getting their foot in the door they ascertain the level of interest and what changes they need to make in their project to make it more fundable by the grantor.

Your district grants office should look at all the possibilities that your linkages can provide before you seek funds from a grantor with whom you have no contacts.

The District Grants Office's Role in Coordinating Preproposal Contact with Grantors

Preproposal contact is one of the most critical steps to grants success. Why? Contact with grantors in advance of writing a proposal allows grantseekers to do the following:

- Confirm their research

- Learn about changes, additions, and new grantor interests

- Avail themselves of valuable information that will help them prepare their proposals (whether in the form of copies of successful grants, newsletters, or priority statements, this information can be incorporated into the project and proposal)

- Understand the proposal review process and how they can become a reviewer

In short, preproposal contact confirms how your grantseekers can incorporate more of the potential grantor's concerns and perspectives in their proposals.

Preproposal contact is also the area that poses the greatest challenge to grantseekers. Even when they know it will help them, they are reluctant to embrace the practice. Your district grants office can provide the initial support for taking this step with a minimal amount of work. You can play a pivotal role in supplying grantseekers with research on potential grantors and access to the friends of the school system who may help them get a foot in the door. In addition, your proposal sign-on system will ensure that contact is made only with those grantors who have been preapproved.

Review the following worksheets and suggestions and decide which services your district grants office will provide to help your grantseekers with preproposal contact and what aspects of preproposal contact you will encourage your grantseekers to take responsibility for. Just remember that leaving the step of preproposal contact solely up to your grantseekers may adversely affect your district's grant acceptance rate.

I ask many grantseekers why they avoid preproposal contact. Their answers vary, but there is one consistent theme: most people would rather write a proposal and place it in the mail than risk having their ideas rejected in a face-to-face meeting.

Whatever their reasons, you must help your grantseekers put them aside. Point out that preproposal contact is less intimidating if they do their “grants homework” and know enough about the prospective grantor to ask intelligent questions that reflect their knowledge rather than expose their ignorance.

Remember that using your district's linkages will help break the ice and that your volunteers may have much less anxiety about contacting grantors than you or your grantseekers. Ask a volunteer who has sales training for help. She or he may be able to make a cold call on a grantor without any problem.

Whoever contacts the prospective grantor should first review the appropriate grantseekers matrix (Figures 4.5–4.12) to reconfirm the values and interests of the type of funder selected for approach. She or he should then review the research collected on each specific grantor. Naturally, any procedural information gathered on a particular funding source should be followed. In general, however, the following suggestions will be helpful.

How to Contact Government Grantors

Contact government agencies by e-mail, letter, phone, and in person, when possible. The first step is to send the agency a letter or e-mail requesting program information and to be put on the agency's mailing list. When appropriate, use the Sample Letter to a Federal Agency Requesting Information and Guidelines (Figure 6.9). Before doing so, check your federal research to see if the agency has provided an e-mail or website address. It is becoming increasingly common for federal agencies to provide program information and even applications on the Internet.

Next, telephone the agency. The Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (CFDA) usually gives the program officer's name and the agency's phone number. Keep in mind, however, the possibility that no one in the agency may have ever heard of the individual because she or he transferred to another office quite some time ago.

Introduce yourself to the person who answers the phone and tell him or her that you are calling for information concerning a grant program. Identify the program by the CFDA reference number and name and ask to speak to the program officer or to someone who can answer a few questions.

It may take one or two referrals to reach the person knowledgeable about the program. Be sure to always ask for the name of the person you are talking to and the phone number and name of the individual you are being transferred to.

Through research, your grantseekers should have collected a considerable amount of information about the potential grantor. This is a good opportunity to validate it. For example, the deadline dates and appropriations in the CFDA can be checked for accuracy.

Tell your new contact what you want! Remember, there are more staff involved in the government grants process than in the foundation or corporate process, and the rules governing freedom of information must be adhered to in tax-supported grantmaking. Staff members are generally willing to provide information.

Your objective is to validate the research that led you to believe that the program was a good match for the project your grantseekers want support for and to discuss their approaches to solving the problem. Ask if you could send the grantor a one-page concept paper and call after it has been reviewed. Also, ask to be put on the grantor's mailing list to receive guidelines, application information, newsletters, and so on.

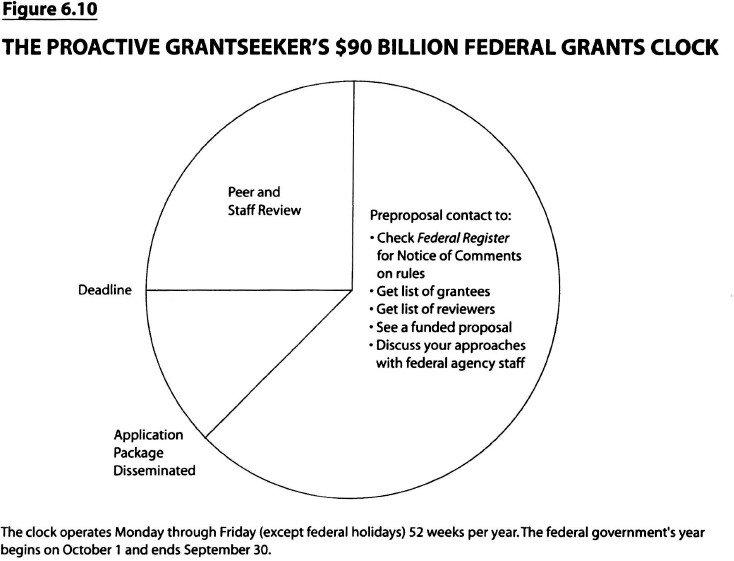

Review Figure 6.10 and then ask where the agency is in its grants cycle.

Ask if the agency published information about its rules in The Federal Register. If so, request the date of publication and page number.

Request a list of last year's grantees. Ask if the list is available on the Internet, or if they will send you a copy. This list of grant winners will help you determine if your applicant school even stands a chance or if it would be better to develop a consortium with other districts, join with your intermediate district, or become part of a college or university's grant. The list of grantees will also tell you who got how much grant money and for what type of projects.

Ask the agency official for information on the agency's peer-review system. Although the Federal Register may have information on the points that the reviewers award for each section of a proposal, you need to know who reads the grant application. Knowing the types of reviewers and the reviewers' backgrounds will help your grantseekers decide what writing style to use and how to construct their proposal. In addition, you should ask the program office how someone from your district could become a reviewer.

After the information-gathering phone call is over, the best strategy is for you, one of your grantseekers, or a volunteer to visit the federal agency in Washington. In a two- or three-day visit contact can be made with several possible funders for your schools' different projects.

Some federal programs actually suggest a preproposal meeting. These agencies want potential grantees to submit the best proposals, even if the agencies are unable to fund them. The better the proposals and the greater the number of requests for funds, the more they can prove that their program is needed, should be continued, and should receive increased appropriations.

You could also invite the funding official to visit your school district or applicant school to observe the problem firsthand. The funding official may come if you invite other schools and districts to an informative session on grants presented by the agency.

You may also ask the program officer if he or she plans to attend an education conference or professional meeting being held in your area in the near future. If so, you, one of your coworkers, or one of your grants advisory group members may be able to meet with the official there.

Who should represent the district at such a meeting? If one of your grantseekers cannot attend, send a volunteer or an advocate from your appropriate grants advisory group. Ideally, a district representative (either you or a coworker) and an advocate should go to the meeting together. Two is the magic number when it comes to representation.

Whoever goes, be aware that dress is important. Federal program officers generally dress quite conservatively. However, program officers at the National Endowment for the Humanities usually dress more casually than those in the Department of Education. Generally, the older the bureaucrat, the more conservative the dress.

Dress for Success by John T. Malloy has a section on how to dress for meetings with government bureaucrats. Although many individuals in the world of education are offended by the notion that people are judged by how they are dressed, it is worthwhile to read this book. Malloy's work was originally funded by an education grant. The purpose of the grant was to determine whether classroom leaders' style of dress had an impact on students' learning and retention; research indicated that indeed it did. Very few educators ever read the research findings and fewer still improved their dress habits because of them, but the important point is that your representatives will be judged by what they wear and therefore should dress accordingly.

What should you or other representatives bring to the meeting? Bring materials that help demonstrate the need. These may include photographs and short audiovisual aids (three to five minutes long), such as filmstrips, videotapes, and slide presentations. You can bring a laptop to present computer-generated materials such as a short, full-motion production with sound, but remember that federal offices are often small and may lack sufficient electrical outlets.

In addition, bring information on your community, school district, individual schools, or specific classrooms. But never leave a proposal behind. Federal bureaucrats know that if you bring an already written proposal with you, you are not likely to change it to incorporate any of their suggestions.

Bring a list of questions to ask the program officer. The questions should reflect your knowledge of the Federal Grants Clock and be aimed at validating information you have already collected about the funding source.

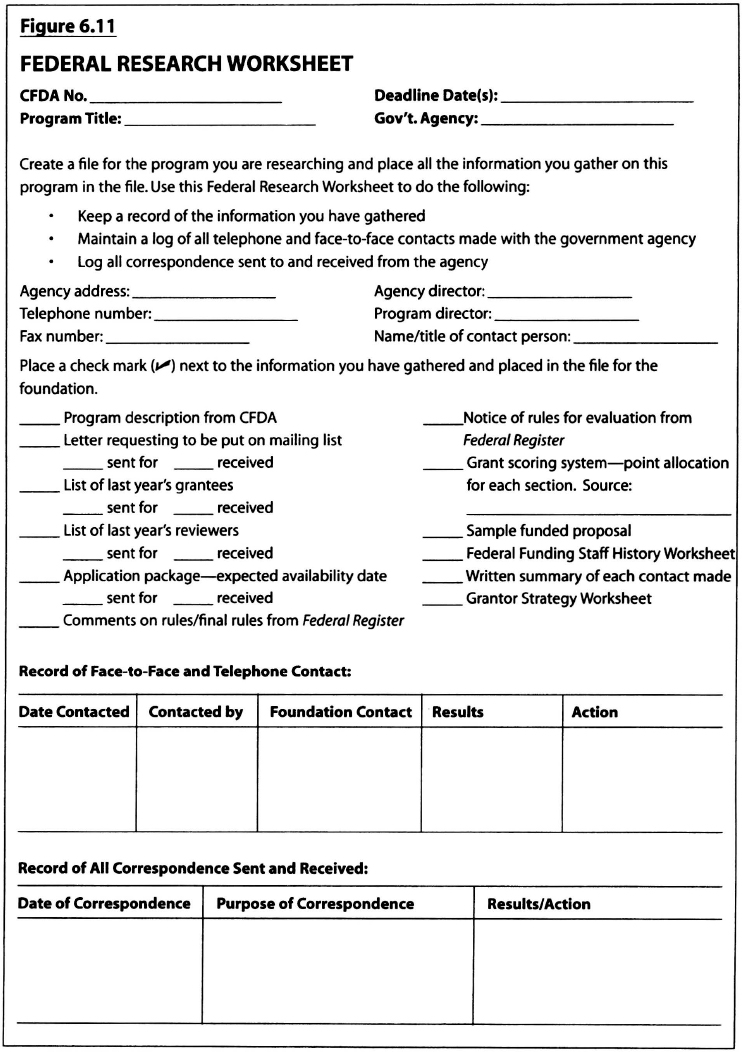

Be sure to file copies of all the information gathered on a prospective government funding source and that all contacts and correspondence are recorded on the Record of Face-to-Face Contact, Telephone Contact, and Correspondence that is part of the Federal Research Worksheet (Figure 6.11). In addition, all information collected on agency personnel should be recorded on the Federal Funding Staff History Worksheet (Figure 6.12).

Contacting Foundation Funding Sources

Most foundations do not respond to requests for information. If your research states “no contact except by letter of inquiry, concept paper, or letter proposal,” do not send a letter requesting information and guidelines. For those who state that reports or guidelines are available, follow these suggestions.

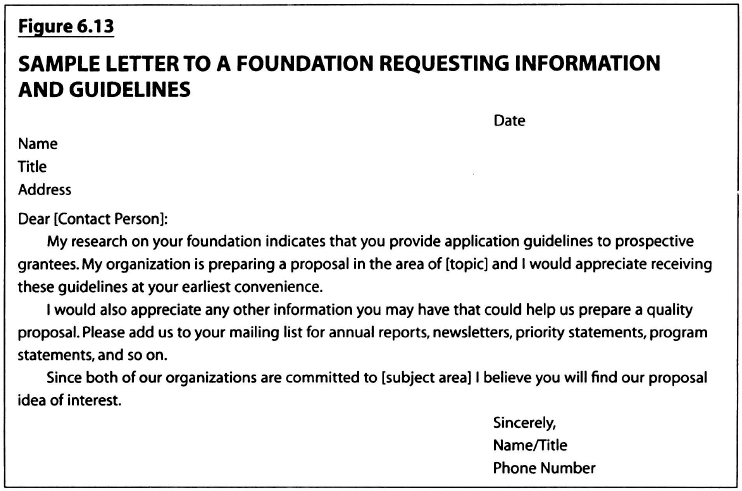

You may request general information, grant application guidelines, annual reports, and newsletters. The Sample Letter to a Foundation Requesting Information and Guidelines (Figure 6.13) can be used with national general-purpose, special-purpose, community, and family foundations, but not with all foundations in these categories. Use the letter to contact only those foundations that state in resource materials such as The Foundation Directory that they have application guidelines available.

Note that this is a letter asking for information only. It is not a proposal. If there is no response to it, a telephone call to the foundation is justified.

But, as probably fewer than a thousand foundations actually have offices, telephone contact is very often impossible. In addition, many of the entries in foundation resource directories do not give telephone numbers. Even if a phone number is listed in an entry or on an IRS tax return, do not call the foundation if its description clearly states that there should be no contact except by letter. However, do not despair. Remember that the 40,588 foundations with no offices still have board members that may be contacted through a linkage with a volunteer or staff member.

If you have not gotten a response to your letter, and you are not aware of any instructions prohibiting telephone contact, by all means telephone the foundation and try to arrange a personal visit. If a face-to-face meeting is not possible, use the phone call to ask the same kind of questions you would have asked at a meeting. Ask the foundation official if you can e-mail or fax a one-page summary of your ideas to him. Also ask if you can call him back to discuss the ideas. Arrange a mutually convenient time to call. A conference call involving a linkage person would be ideal.

Steps for Contacting Foundation Grantors

If permissible, call the contact person. The dilemma is deciding who should establish a relationship with the funder—a district administrator, grants coordinator, or one of the grantseekers. Because many educators are reluctant to make preproposal contact, you may decide to help your grantseekers get started and then step back.

In any event, the caller may find it helpful to review the needs data first as a reminder that she is calling on behalf of the school district, school, students, field of education, or whatever it is, rather than for any private motive. This may help alleviate nervousness.

The caller should introduce herself and state the purpose of the call. (If a secretary or administrative assistant is reached, ask to talk to the foundation director or to a staff person best able to answer questions.) As with government grantors, one purpose of the call is to validate the information already gathered on the foundation. The caller's questions should reflect knowledge of the foundation's granting pattern and priorities. Another purpose is to ascertain the foundation's interest in the grantseekers' approach to the problem or in increasing educational opportunities for children.

It is important that the caller demonstrate that she is different from other grantseekers and that this foundation has been purposefully selected. For example, the caller may say, “I am contacting the Sebastian Jessica Foundation because it has demonstrated its desire to see expanded parental involvement in elementary and middle schools. My research shows that 40 percent of your funds in recent years were committed to this area.”

As with government grantors, the caller should tell the foundation funding source what she wants. For example: “I would appreciate five minutes of your time to ascertain which of the two or three approaches I have developed for the XYZ School would elicit your foundation's support and appeal favorably to your board.” Note: You may use the fax approach here to build their interest. For example: “I would be happy to fax a short summary of the proposed solutions to you and to discuss them with you after you have had time to look them over.” E-mail with an attached short file is becoming more acceptable. You should inquire about this option.

Ideally, the next step is to meet face-to-face with the funder. You can either go to his location or invite him visit to visit you at the applicant school. By visiting the school, he can observe your district's students and see the needs population or problem firsthand. In either case, the funder will expect to pay his way to visit you, just as he will expect you to pay your way to visit him.

If a visit to the funder is possible, who should go? Whether you visit the foundation or it comes to you, your team should be small—usually no more than two. Select an active and concerned volunteer from your appropriate grants advisory group who is donating his or her time to the proposed project. The other person may be yourself or one of your grantseekers.

The team's style of dress should be similar to that of the foundation official. Again, your grantseekers' research will come in handy here, as well as the book Dress for Success. It is important to remember that your goal is to project the appropriate image to the prospective funding source. This is not the time to assert your individuality or state your values. The most important outcome of the visit is that the grantor hear your ideas.

What you bring to the meeting is extremely important. Focus on your objective. What do you expect to accomplish in a person-to-person visit with the potential grantor? You want the following:

- Agreement on the need or problem to be addressed

- To induce the prospective funder to discuss its interest in your grantseekers' solution

- Information on the grants selection process so that your grantseekers can tailor their approach

- To validate your research and in particular to ascertain the appropriateness of the size of the potential grant request

To avoid the common mistake of jumping directly to the money issue, concentrate on bringing material that solidifies agreement on the need or the problem. In many cases, the grantor has difficulty seeing the problem through the eyes of a student or an educator. Use the following techniques to help the funder develop insight into the problem. Your materials should be aimed at educating, rather than convincing, the grantor.

A well-developed presentation on a laptop computer can be very effective, but keep it simple and to the point. Avoid projection systems. Be careful about using technology when requesting a small grant. Your laptop should not cost more than what you are requesting.

A short (three- to five-minute) videotape or slide show, especially one produced by students, can demonstrate the problem very effectively. Whether it is about alcohol abuse or zoology, these tell a compelling story because they enable the funder to see the nature of the need. Or a picture book that documents the need may provide the starting point for a discussion of the problem.

Again, the objective of the meeting is to first establish agreement on the need for the project and then to ascertain the funding source's interests and to discuss several approaches or solutions.

Recording Foundation Research and Preproposal Contact

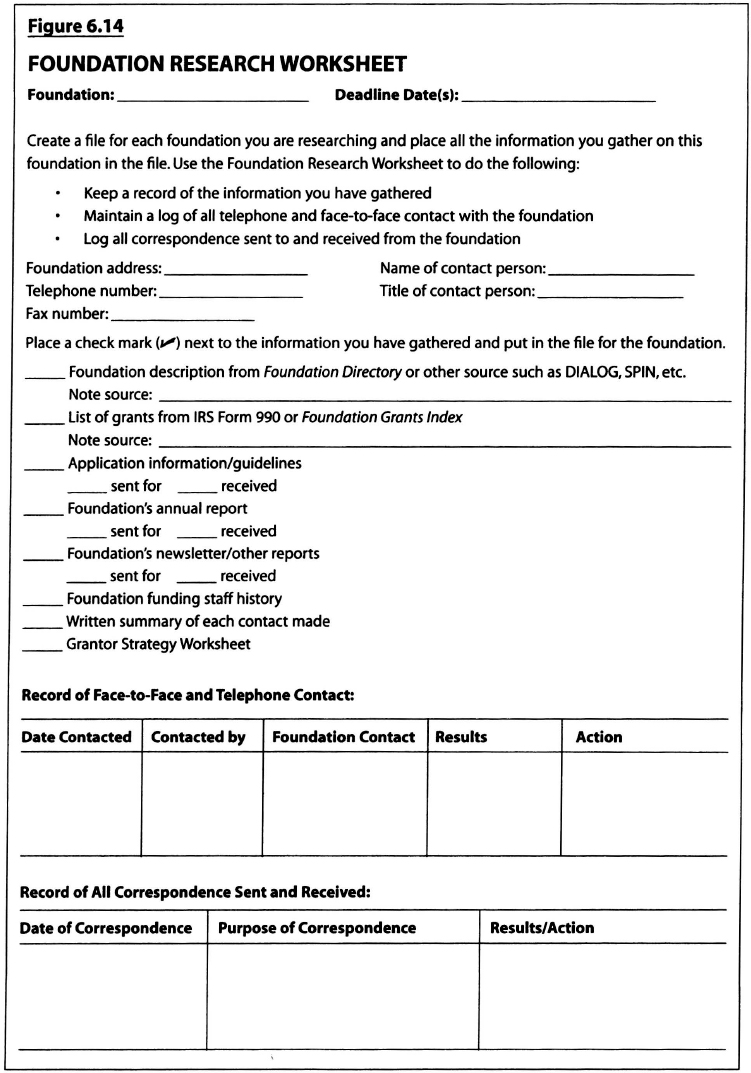

The purpose of preproposal contact is to validate your grantseekers' research on the funding source and to add to that knowledge so that your district can develop a grant-winning strategy. You want your grantseekers to be organized and to take advantage of every possible time-saving technique. Therefore, your district grants office should initiate an electronic or conventional file on every foundation funding source your grantseekers are researching and thinking about approaching. These files should be continually updated and kept together in alphabetical order. Your grantseekers may make copies of these files for their own records, but the original files should be stored in the district grants office. This is a great start toward an organized grants effort.

The Foundation Research Worksheet (Figure 6.14) should be filled out for each foundation that is a possible source of funds. This worksheet will help you keep an up-to-date record of the information and materials gathered. All contact with the potential funding source should be logged on the Record of Face-to-Face Contact, Telephone Contact, and Correspondence portion of that form, even contact that reveals that the grantor has no interest in your project.

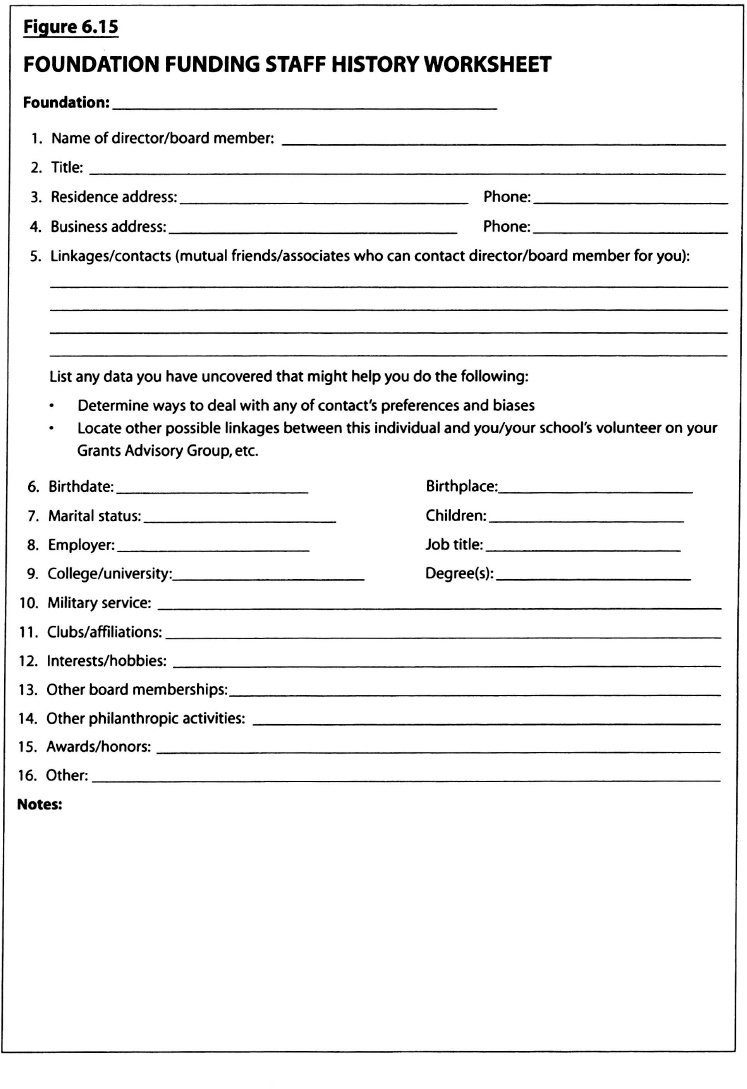

Collect as much information as possible on foundation officers, board members, and trustees. This information can help you and your grantseekers figure out strategies to deal with any preferences and biases you may encounter in your contact with a foundation. It will also help you pinpoint links between the foundation, your school district, a volunteer on your grants advisory group, and so on.

Use the Foundation Funding Staff History Worksheet (Figure 6.15) to record the information collected. Keep the worksheet in the appropriate file.

How to Contact Corporate Grantors

Your district grants office should open a file on corporations that may be potential grantors for your schools' projects. Because many corporations are more responsive to an approach through their employees or sales representatives, you may want to line up your linkages before contacting the actual grantor.

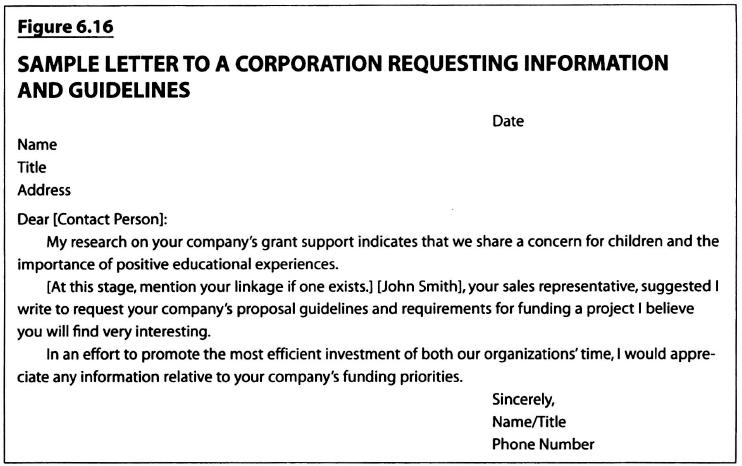

The Sample Letter to a Corporation Requesting Information and Guidelines (Figure 6.16) can be sent to those corporations that actually have a grants staff and a preferred proposal format or application form. In general, the larger the corporation, the greater the chance it will have proposal guidelines.

Before you follow up on the letter by telephoning the corporate grantor, review the reasons why you think the company would value your school's project and how the project relates to the company's products or workers. If you do not know who the corporate contact is, ask whoever answers the phone who would best be able to answer your questions about the corporation's grants process. It may be a local plant manager, salesperson, or corporate granting official.

As with foundation and government grant sources, state the reason for your call; for instance, “I am calling to discuss the opportunity of working together on a grant that has mutual benefits to both the XYZ School and the ABC Corporation.” Request five minutes of the person's time to answer your questions and suggest that you fax, e-mail, or mail them background information. The purpose of sending background information is to solicit comments so that you can tailor your proposal to the company's needs. Be sure to let the contact know that you are presenting your school's proposal at this point.

Summarize the research that has led you to contact the company. Explain that you are not approaching a hundred corporations but only a select group.

If there is a possibility of a conference call, use any linkages and local employee support that you can. For example, you can demonstrate the voluntary involvement of the corporation's employees in your school district by including one of them in the call.

Corporations may actually spend more time reviewing grants than foundations do. One possible reason is that they have employees and offices, even though employees who act as corporate grants contacts may have several other job responsibilities. This often makes it possible for a grantseeker to meet with the corporate grantor in person.

Because of the growing involvement of corporations in programs such as “Adopt a Classroom,” more and more districts are developing historical relationships with the corporations in their area. Naturally, your district grants office should make records outlining the corporation's history with the school district available to the individuals planning to visit the company.

You may even want to invite the corporate person to visit your applicant school to see the problem firsthand and to discuss the corporation's interest in the approaches developed to reduce the problem.

A volunteer might be the best person to meet with a corporate contact. You and your coworkers are being paid by your district to represent it and its schools, but a volunteer is donating time and may even lose income to represent the district. Corporations will be impressed by the quality, commitment, and number of volunteers that your schools can mobilize.

But don't overwhelm the corporate funder with a massive team. Two well-chosen and carefully instructed representatives will be most effective. Again, they should dress similarly to the people they will be meeting and strive to project a serious, businesslike appearance. They should bring along information on the need for the project. As with other funding sources, one of the following might be included:

- A short videotape that documents the need; include facts and, if possible, a testimony or case study for human interest

- A slide-audiotape presentation on the problem or need

- Pictures, charts, statistics, and so on

As corporations have their own management style and vocabulary, it might be a good idea to ask a corporate member of a grants advisory group to help you prepare a short, corporate style presentation to the funding source. This presentation might include colored charts and transparencies.

Recording Corporate Research and Preproposal Contact

Create a file for each of your district's corporate prospects. The corporate files should be kept together in alphabetical order. Again, this will help organize your district's grants effort.

Make sure that contact with each corporate prospect is logged on the Record of Face-to-Face Contact, Telephone Contact, and Correspondence portion of the Corporate Research Worksheet (Figure 6.17). The worksheet will help your office maintain an up-to-date record of the information gathered. It should be updated as additional information and materials are obtained.

Just as it is important to gather personal data on foundation officers, board members, and trustees, it is also important to gather personal data on corporate executives and contributions officers. You can uncover some information on corporate executives by examining various corporate resource materials such as Standard and Poor's Register of Corporations, Directors and Executives.

The more information gathered, the better the chances of developing an approach that will appeal to the funding source. In addition, your chances of identifying more linkages to the corporation will increase. However, please note that your grantseekers should not rule out a particular corporation as a funding prospect simply because they are unable to gather personal data on the corporation's funding officials.

The corporate Funding Staff History Worksheet (Figure 6.18) should be used to record the information collected. The worksheet should be stored in the appropriate corporation's file.

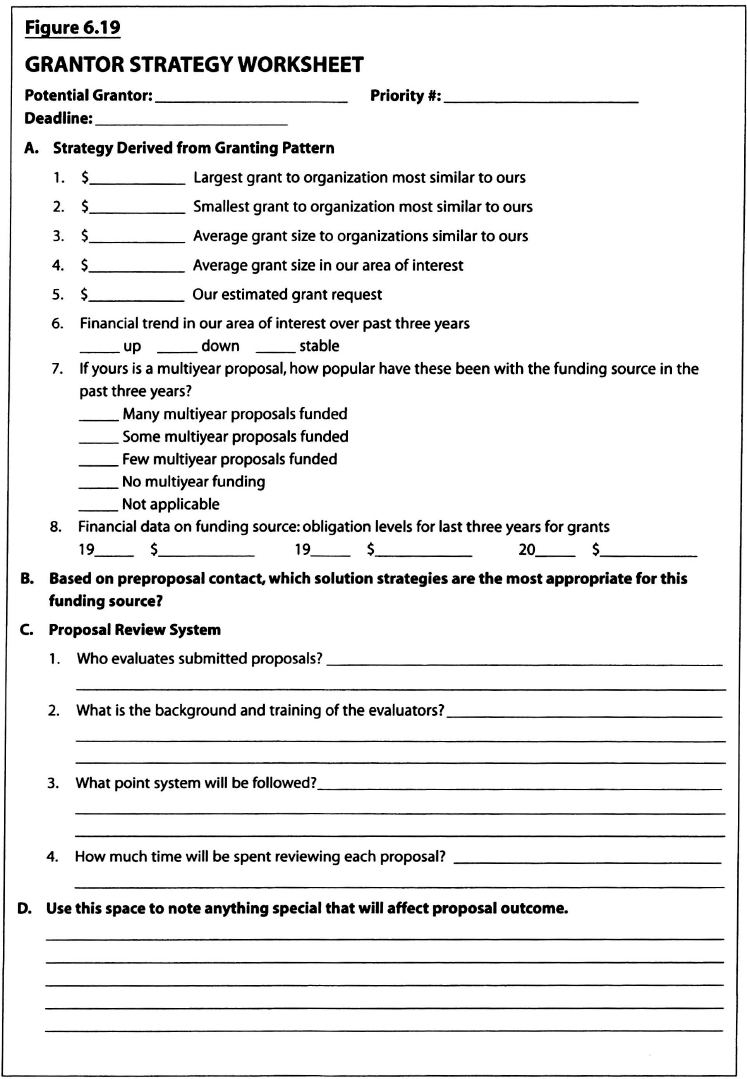

The Grantor Strategy Worksheet

This worksheet (Figure 6.19) should be completed for each funding source your grantseekers are planning to submit a proposal to. It will help you assist your grantseekers in tailoring their proposal to the potential funder's viewpoint.

Every attempt should be made to analyze the funding source's granting history. Even if preproposal contact is not possible, you must at least make sure that the amount your grantseekers are requesting fits the funding source's granting pattern.

Think about who might collaborate with your grantseekers on their proposal and what other groups could submit it so that it might better fit the funder's requirements.

If at all possible, find out who will read and evaluate the proposal. For example, will it be read by staff members? Board members? Program personnel? Outside experts or reviewers? Besides helping your grantseekers write the proposal, this information will be vital to performing a mock review.

The prospective funding sources should be ranked by potential. At this point, your grantseekers should not spend much time writing the proposal. Instead, they should be investing their time analyzing their best prospects for funding.

Although some pieces of vital information will probably be missing, encourage your grantseekers to devise the best strategy they can based on what they know.

Developing a district grants booklet on the concept of preproposal contact has a positive effect on your grants effort. Providing grantseekers with a suggested process for making each type of contact reduces their anxiety and increases their readiness to make the contact. It is unfortunate that many school districts ignore the issue of access to potential grantors. Your grantseekers deserve to understand this process.

Use the worksheets and information in this chapter to help you develop a booklet tailored to your district. The title of the booklet could be “How to Get Approval to Contact Funders and the Preproposal Contact Support Services Provided by the District Grants Office.” This would make it clear to your grantseekers that your office has a sign-on system and services that can help them. And even if it doesn't, you could still provide a preproposal contact booklet containing helpful information, worksheets, checklists, and so on.

If your system is more advanced it may be appropriate to include a section in the booklet on the role of the grants advisory committee and a description of your system for recording linkages.