Chapter 7

Moving from Idea to Project Plan

THIS CHAPTER HELPS grantseekers select the best proposal strategy and create a grant-winning plan that provides for sound project management.

Much of the work of a successful district grants office consists of encouraging and monitoring the pace at which grantseeking occurs. Some zealous grantseekers may view the steps to developing a credible, organized, and ultimately successful proposal as roadblocks inflicted by a system that requires too many forms, worksheets, and approvals. It is usually those with a great idea but a poorly developed plan who create the most problems.

The time to develop an easily administered grant is while it is being constructed, not after the award notice. Sound grants administration principles are grounded in proper planning. An easily administered grant is founded in a proposal that provides an analysis of the tasks that must be carried out to bring about the suggested change and includes the job description of all staff; the requirements for staff; consultants' work descriptions; the cash flow by activity; and an inventory of all supplies, materials, and equipment needed.

In reactive grantseeking, there is a mad rush to finish the proposal by the deadline and no time for preproposal contact with the funder or for review and rewriting. The budget is usually created in the final hour before the proposal is signed and submitted. By then, asking the proposal developer to slow down and create an organized planning document or a spreadsheet that outlines all the activities or methods so cash flow can be projected is out of the question. But should there be a mistake or a legal or credibility problem, the district grants person will be the first to be called before the superintendent.

Your school administrators and district grantseekers must be educated to the increased chances of grants success if they follow a grants plan such as the one suggested in this chapter. The credibility and image of the entire district rest on each proposal submitted to a grantor. Even when grantors must reject your district's proposal, you want them to have read a well-organized document. Some grantseekers mistakenly think they can dazzle them with their brilliance and baffle them with their bull. But grantors usually subscribe to the KISS concept—Keep It Short and Simple. They are offended by disorganization because it wastes their valuable time.

A quality proposal is based on an easily understood plan that provides the rationale for the proposed activities and expenditures. Some grantors require that it be described in a budget narrative form. Others prefer to see it visually displayed on a spreadsheet. Even when not required by the grantor, your grant writers should complete a spreadsheet that provides the detail necessary to prepare and negotiate a budget.

Both you and your grantseekers need a project management system that allows you to track each project's progress, locate the equipment purchased under each grant, and maintain your schools' credibility within your district and outside of it. Grantseekers often complain about their inability to control and expend grant funds that are accepted by their school district for proposals they have written. This complaint can be avoided by employing an effective project management system.

Up to this point in your proactive grants system, your grantseekers should have documented a problem and come up with several possible solutions for it. Some will want to send the prospective funder a proposal that outlines several solutions, hoping the funder will select the one it prefers. But you should encourage submitting only proposals with one solution—the solution that will appeal most to the grantor.

Your grantseekers' research and preproposal contact should have helped them choose the solution or approach that most likely offers the prospective funder what it wants. If it was possible to procure a copy of a proposal the grantor has funded in the past, this also should have provided them with an idea of what objectives, methods, and format the funder prefers.

Research should at least have uncovered the range of grant awards, including the high, low, and average grant size; geographic preferences; and types of projects preferred. If the proposal requires more funds than a single grantor is likely or able to invest, you will need a project plan that identifies several prospective grantors and the amount of funds needed from each. The plan should also clearly delineate which parts of the project each grantor will fund.

As your grantseekers become more and more involved in developing proposals, you must remind them to view their proposals through the eyes of the funding source and to make every effort to tailor each proposal to each prospective grantor. This reinforces the values-based approach to grantseeking. Remember, the funder may not see the methods, budget, or grant request the same way you and your grantseekers do. In fact, each type of grantor will view these differently. For example, government grantors require longer, well-organized proposals that allow them to easily identify matching or in-kind contributions and may require a written description linking each budget expenditure to a method. In contrast, most corporate and foundation funders prefer a short letter of proposal and a businesslike approach that relies on cost analysis of each step in your plan.

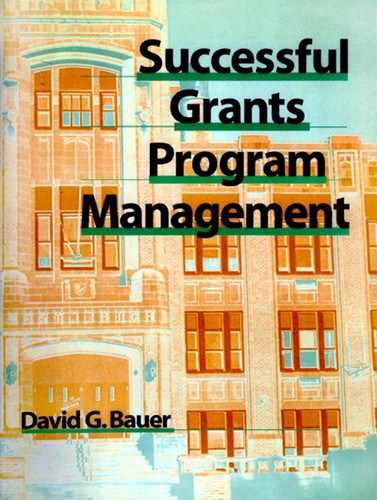

Whatever their type, all grantors require that you have a clearly defined plan. Just as good teachers have well-developed lesson plans, funding sources require grantees to have well-developed plans before they give funds. The Project Planner (Figure 7.1) should help your grantseekers format their grants. (The Project Planner is presented here with permission from the American Council on Education.)

The Project Planner

Think of the Project Planner as a lesson plan or spreadsheet. The proposed plan is developed when the grantseeker (proposal developer) is ready to focus on the solution or approach believed to be the most interesting to the prospective grantor. The plan must show the percentage of time and effort the key staff spends on the project, outline consortium arrangements and the use of consultants, and identify any matching or in-kind contributions the grantseekers' school will provide.

The Project Planner helps your grantseekers develop a clearly defined proposal methodology, plan, and budget. Once completed, it allows them to define and refine several aspects of the project:

- An adequate staff pattern that describes who is needed to do what tasks when (helping ensure that job descriptions match the tasks that must be accomplished)

- An easily scanned overview of the prescribed activities and how they relate to costs and the attainment of the objectives

- A logical framework on which to evaluate the tasks performed by consultants

- A detailed analysis of the materials, supplies, and equipment related to each objective

- A defensible budget and cash forecast

- An efficient way to keep track of in-kind or matching donations

- A basis for dividing costs among multiple funders

- A working document that makes it possible to assess the involvement of multiple organizations and the responsibilities of consortium participants and subcontractors

Project Planners appeal most to funding sources that are familiar with and use spreadsheets themselves (corporations, for example). Recently they have become an addition to government proposals. Federal program officers and their grant and contract officers are now trying to pinpoint inflated budget items, and will push grantees to agree to carry out their proposal for less money than originally requested. They are simply trying to negotiate, a process that requires give-and-take. But most grantseekers just take what the federal grantor says it will give. The Project Planner helps your grantseekers to truly negotiate.

Standard federal budget forms use broad budget categories. These make it difficult to demonstrate that a project will be compromised if less money is granted than requested. But a Project Planner shows how a reduction in funds will impede methods or activities and negatively affect the proposal's objectives. This link between cause and effect is crucial to negotiating the final award because the achievement of a proposal's objectives is shown to be directly related to bringing about the degree of change desired by both the grantee and the funder. The Project Planner allows grantseekers to present a clear picture of the relationship between project personnel, consultants, equipment and supplies, and the accomplishment of their school's proposal.

If you and your grantseekers are not familiar with spreadsheets, the Project Planner might seem a bit overwhelming. But there are many ways to complete it, and the only real mistakes one can make are mathematical (incorrect addition, multiplication, and so on).

Look at the Project Planner as a tool that helps your grantseekers identify the costs of carrying out the methods and activities in the proposed plan and how those costs will be divided among all partners in the agreement. They decide how detailed the breakdown of activities should be. The more detailed the breakdown, the easier it is to document the costs assigned to each activity and to defend them in budget negotiations.

The basic purpose of the Project Planner is to provide a clear plan that results in the educational change described in the project objectives. Therefore, we must look at how to develop objectives before we examine the general guidelines for filling out the Project Planner.

Objectives

The district grants office should remind the proposal developers how important it is to develop objectives that demonstrate the type of change the grantor values. Proposed plans should meet or exceed the educational change defined in their objectives. My rule is: no objectives, no need for a plan; no plan, no chance for a grant and no need to bother grantors.

Your district grants office will find that it pays off to provide grantseekers with guidelines for constructing quality objectives that result in quality proposals, which in turn lead to grant awards. Include guidelines for constructing objectives in your district's booklet on how to write a grant-winning proposal.

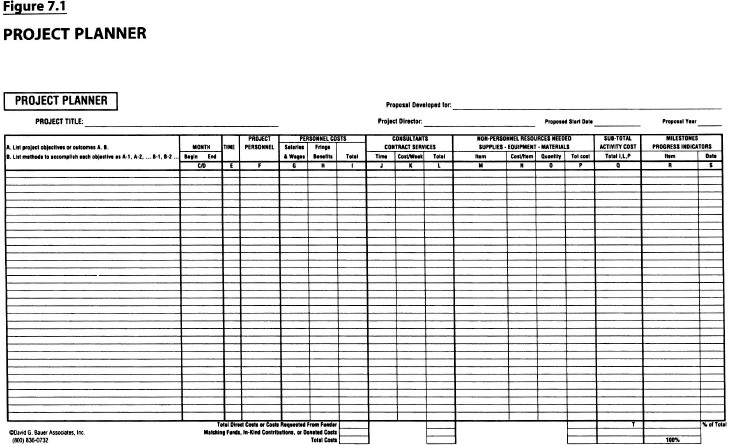

A well-constructed objective tells the funder what will change and how much if funds are granted. Graduate training may have given you experience in setting affective, cognitive, psychomotor, and behavioral objectives, but many grantseekers do not understand the difference between an objective and a method. Some mistakenly write objectives that focus on the approaches, steps, or methods that will be used to bring about the change. This confuses what will be accomplished with how it will be accomplished. Objectives deal with what will change; activities and methods tell how it will be brought about.

Objectives should be reviewed to be certain that there is more than one way to achieve each one. If the objective in question suggests that there is only one possible approach, then you are dealing with a solution, not an objective. A well-developed objective focuses on an outcome, implying that more than one strategy could reach it. If your grantseekers are confused about the difference between objectives and methods, ask them why they are performing a particular activity. Their reply may give them a clear sense of what will be measured as they close the gap in the area of need.

An objective provides a measurable way to see how much change should occur by the conclusion of the project. A method tells how it will be accomplished. Objectives say what you want to accomplish, methods say how. Being aware of this distinction can dramatically strengthen a proposal.

Developing objectives may appear tedious, especially when your grantseekers are eager to move on to proposed solutions and proposals. But keep in mind that well-written objectives that focus on measurable change do the following:

- Make the proposal more interesting and compelling to the funder

- Enable grantseekers to measure the changes the proposal suggests

- Increase their school's and the district's reputation as a source of excellent proposals

The Understanding and Creating Measurable Objectives Worksheet (Figure 7.2) may help your grantseekers develop objectives. In addition to suggesting that they review the guidelines for constructing objectives in your district's booklet on how to write grant-winning proposals, you may also suggest that they consider the more detailed guidelines in the Teacher's Guide to Winning Grants (see bibliography), but, in general, a well-written objective includes an action verb and statement, measurement indicator, performance standard, deadline, and cost frame.

Action Verb and Statement

The direction of change to be accomplished is based on the information provided on the Needs Worksheet (Figure 3.3) and Goals Worksheet (Figure 3.5). Remember, you and your grantseekers are not suggesting or promising that a goal will be met or a gap entirely eliminated by funding the proposal. You are suggesting that a measurable part of the gap will be closed by means of its prescribed actions, methods, and activities. You are not certain that your proposed approach will be entirely successful, but you believe it will benefit education by at least partially closing the gap and expanding knowledge of what works.

For instance, any project aiming to promote educationally responsible behavior in parents, teachers, and students is unlikely to close the gap entirely. Thus a grant proposal should suggest that the project will lessen, not eradicate, educationally responsible behavior in parents, teachers, and students.

When you ask your grantseekers what will change as a result of a project, some answers will have to do with knowledge and others with values and feelings. In the example just cited, some might specify outcomes in the area of cognition or knowledge, others in the area of attitudes and feelings. Because such issues are complex, suggest that your grantseekers ask for help from the college or university faculty members on their grants advisory group when constructing objectives.

Measurement Indicators

Just as there are many ways to accomplish objectives, there are several ways to measure change. Your grantseekers should begin by asking themselves what students will do differently after experiencing the methods aimed at solving the problem and how the change can be measured. Are there standardized tests or evaluation instruments for this purpose? If not, can a way of measuring the desired change be developed?

In the sample project to increase educationally responsible behavior in parents, teachers, and students, the reduction in the gap between what exists now and what ought to be can be measured in a variety of ways. For instance, we could look for behavior that indicates a developing sense of responsibility: improved grades, decreased absenteeism, higher percentage of students successfully completing their grade, more time spent on homework, more teacher-parent contacts, more parent-child talks about education, and less time spent watching television. We might even develop an Educational Responsibility Scale that contains questions aimed at surveying many of these points.

Performance Standards

A grantor will look at the objectives, note the size of the grant requested, examine the measurement indicators, and compare the amount of the request with the expected amount of change.

For a multiyear project, your grantseekers may want to create objectives stating a one-year goal for change and increase the amount of expected change over subsequent years. For example, in the educationally responsible behavior project, the objective could be to achieve a 25 percent increase in one year and a 40 percent increase by the end of year two.

Deadline

Most government grants are for one year because of the way the federal budget appropriation cycle operates. However, there is a movement in Washington to allow multiyear awards because it is difficult to demonstrate behavioral change in just twelve months. In addition, it often takes a good part of a year just to develop and conduct pretests that provide the baseline data for post-tests.

Thus far in our discussion, the objective of our sample project might be expressed like this:

To increase educationally responsible behavior in parents, students, and teachers in the XYZ Elementary School (action verb and statement) by 25 percent (performance standard) at the end of one year (deadline) and by 40 percent (performance standard) at the end of year two (deadline), as measured by the Educational Responsibility Scale (measurement indicator).

Cost Frame

Your grant developers should include the cost of accomplishing the change in the body of the objective. This will demonstrate that they have total command of their proposal. They know what they will measure, how they will measure it, when it will be accomplished, and how much it will cost. This provides a stark reminder of how much it costs to accomplish educational change. The one catch is that your grant developers cannot know the cost until they have completed their project planner. Now that they have a proper objective, they are ready to tackle this task. Caution them to use pencil when completing the project planner so that corrections and changes can be made easily.

Completing a Project Planner

The following general guidelines follow the format of the planner sample shown in Figure 7.1.

Objectives and Methods

In the column labeled A/B, list the project objectives and label each—for example, Objective A, Objective B, Objective C, and so on (if the grantor prefers another format for labeling objectives, use that instead). Under each, list the methods that will be used to accomplish each of the objectives. Think of the methods as the tasks or activities that will be used to meet the need. Label each method under its appropriate objective; for example, A-1, B-1, C-1, and so on.

Month

In column C/D, record the month each activity or task will begin and the month each will end. For example, writing 1/4 signals intent to begin the first month after receiving funding and carry out the activities over four months (sixteen weeks). If the expected start-up month is known, note it here.

Time

In column E, record the number of person hours, weeks, or months needed to accomplish each task listed in column A/B.

Project Personnel

In column F, list the names of key personnel who will spend a measurable or significant amount of time on each task or activity listed and on each objective. (The time has already been recorded in column E.)

Personnel Costs

In the next three columns, list salaries and wages (column G), fringe benefits (column H), and total compensation (column I) for each of the key personnel listed in column F.

Start by coming up with a rough job description by listing the activities each person will be responsible for and the minimum qualifications required. Determine whether each will be full- or part-time by looking at the number of hours, weeks, or months they will be needed. Then call a placement agency to get an estimate of the salary needed to fill the position.

Be sure to include services that will be donated. Put an asterisk next to all donated personnel and remember that these individuals' fringes as well as wages will be donated. Identifying donated personnel is crucial when matching or in-kind contributions are required, and may be advantageous even if not; matching contributions show good faith and make your schools seem a better investment. Indeed, put an asterisk by anything donated (such as supplies, equipment, materials) as you complete the remaining columns.

Consultants and Contract Services

In the next three columns, list the time (column J), cost per week (column K), and total cost (column L) of assistance to be provided by consultants and other contractors. These are individuals not in your normal employ who provide services not normally provided by someone in your district. (Note: No fringe benefits are paid to these.)

Nonpersonnel Resources: Supplies, Equipment, Materials

Use the next four columns to list the supplies, equipment, and materials needed to complete each activity and to itemize the associated costs. In column M list the items; in column N list the cost per item; in column O list the quantity of each item; and in column P list the total cost.

Do not underestimate the resources needed to achieve the objectives. Grantseekers should ask themselves and the project's key personnel what is needed to complete each activity. Again, designate donated items with an asterisk.

Subtotal Cost for Activity

Add columns I, L, and P—the totals of personnel costs, consultant and contract services, and nonpersonnel resources—and note the sum in column Q. Your grant developers can do this either for each activity or for each objective. If they do it for objectives, they will have to add the subtotals for all of the activities that fall under the objective.

Milestones and Progress Indicators

In column R, list what you will give the funding source to show them how the project personnel are working toward the objectives (such as a quarterly report). Think of these as milestones or progress indicators.

In column S, record the dates by which the funding source will receive the listed milestones or progress indicators.

Involving Corporate Volunteers

Corporate volunteers can be extremely helpful in preparing the Project Planner. They may have access to computer software that can develop a spreadsheet and a forecast of cash flow for your project. However, as your school's representative to the corporate world, you must be aware of the problems in communication that can occur when you involve corporate people in developing educational programs.

Many corporate staff have been exposed to business seminars on management by objectives, matrix management, total quality management, and the learning organization, to name a few. The management theory vocabulary, and that of the corporate world in general, is much different from that of the field of education. Hence, confusion can result when an educator and a corporate individual work together to develop goals or objectives. For example, in education, goals are long-range desires. They are normally part of a “guiding statement” and are therefore nonmeasurable and usually nonobtainable. In the corporate world, goals are daily steps taken to accomplish objectives—what an educator would call methods or activities. To make matters even more confusing, objectives in the corporate world are long-range and normally part of a guiding statement; in education they are what we want to accomplish and are measurable.

It is easy to imagine how this difference in understanding could extend to a proposal submitted for corporate funding. It would therefore be wise to ask one of your corporate volunteers to review the proposal prior to submission to ensure that the vocabulary is appropriate for a corporate funding source.

Project Planner Examples

One way to complete a project planner is shown in Figure 7.3. In this sample the project director's salary is being requested of the funder, as are the salaries of two graduate students who will assist the director. The services of the project director and the graduate students are being contracted from West State University. Therefore, their time commitments and costs fall in columns J, K, and L on the Project Planner.

The project director will ask West University's Human Subject Institutional Review Board to examine the procedures involved in getting the students, parents, and teachers to agree to write contracts for change. It is anticipated that she will work half-time on the project for twelve weeks during months one through six and full-time for twenty-four weeks during months seven through twelve.

This case shows considerable matching and in-kind contributions, as indicated by the asterisks. For example, the school district is donating the salary and fringe benefits of the project secretary. In addition, a significant portion of matching and in-kind contributions are coming from the Jones Corporation, which is donating the use of its corporate video production facility.

Although these contributions demonstrate frugality, commitment, and hard work, “overmatching” can become an issue. When a proposal has a huge matching component and requires only a small amount of grant funds, a prospective grantor may conclude that the entire proposal should be funded through matching and in-kind contributions. Still, most matching components are viewed favorably by grantors.

Grant writers sometimes create a second, more detailed project planner once they receive word that their proposal has been awarded. Figure 7.4 shows how Activity A-4 from the previous example could be outlined in more detail. Naturally, cost estimates could also be developed for each of these more detailed activities. Keep in mind that some grantors may require such detail.

Using the Project Planner for Budgeting

It is best that you, the district grants administrator, review the Project Planner with the proposal creators to ensure that they have included all the elements necessary to develop a realistic budget and the success of the plan. With this in mind, several key areas need emphasis.

Budget Development and Negotiation

The budget, in whatever form it is requested, should reflect the Project Planner totals for personnel costs (column I), consultants and contract services (column L), and nonpersonnel resources such as supplies, equipment, and materials (column P). By pointing out the importance of subtotaling the costs for each activity in column Q of the Project Planner, you will be ready to help your grantseekers negotiate a grant award. Beginning to discuss the strategy for negotiating the budget while finishing the plan will enable you to set the stage for an accountable and defensible budget.

The negotiation itself, however, should not be based on the budget categories (personnel, consultants, supplies, and so on). Rather, it should be based on the methods or activities that make up the budget totals.

Review with your grantseekers the effect of reducing funds for each activity. What impact would it have on attaining the change indicated in the objective? You may be able to reduce the size of your request by eliminating an activity or two without having much effect on the project; however, if you eliminate too many activities you will probably not be able to accomplish your project as outlined. Instead, it may be preferable to modify the objective and reduce the amount of expected change or the number of students or participants the project will reach.

The district grants office must be involved in negotiating the final award and in altering the objectives and methods to arrive at the final budget. Overzealous grantseekers can become their own worst enemy. In their desire to please the grantor and their excitement over the grant, they want to appease and appear appreciative and congenial. But they may go too far; it might seem as though they would settle for any amount of funding. Without being given reason to think otherwise, the grantor may come to believe that the budget was not realistic to begin with.

A well-developed Project Planner and a sound budget counter this. Some grantseekers will try to convince you that a district grants administrator simply cannot understand their high-tech plan. Generally they are merely ill-prepared. When completed accurately, the Project Planner can help you understand the proposal and provide valuable assistance in the negotiation of the final award.

The credibility of the school district depends on the impression the grantor gets when negotiating the final award. Your office must be part of that process in order to administer the funds later.

Matching and In-Kind Contributions

The district grants administrator will be required to document any and all costs that have been designated as matching or in-kind contributions.

Each year more grantors are requiring that school districts demonstrate commitment to their projects through a system of contributions. As funding becomes more limited and competition increases, this practice will become even more common.

How does a school district that needs outside funding to accomplish its projects demonstrate that it has resources to donate to a grant? It might seem paradoxical, but try to look it from the funder's point of view: they want to see commitment!

To help document commitment, your grantseekers should consider the time their advisory group members have volunteered to the project. Can this be considered an in-kind contribution? Ask them to review their Project Planner. Are there any personnel costs or nonpersonnel resources that could be donated instead of requested from the funder? Finally, are there any hidden costs in their schools that could qualify as matching contributions? For example, I once worked on a grant proposal that called for developing an in-service course for teachers as a way of effecting change in the classroom. In seeking to meet the funding source's matching funds requirement, a school administrator revealed that under the teachers' contract the district was required to pay each educator a salary increase after completion of the course. We calculated the average age of the participating teachers and the total number of years that the increase would be paid out to all teachers, multiplied this figure by the salary increase, and were allowed to claim the resulting figure as a match.

I cannot guarantee what a grantor will accept as a matching or in-kind contribution, but be creative. Proposal developers should review their project and look for every possible matching contribution. If they have a grants advisory group, the members may volunteer some of the match by lending the use of facilities and donating equipment, printing, travel, and so on.

Cash Flow

As an administrator, you may or may not be praised for helping to develop the proposal, but you will surely be blamed if problems with cash flow arise. You can avoid trouble with cash flow by doing the following:

- Having a project plan that forecasts your cash requirements properly

- Making your school district aware of the cash forecast by pointing it out in the proposal sign-off process

By analyzing the Project Planner, your proposal developers gain the information necessary to determine their cash flow needs. Column C/D of the planner designates the beginning and the end of each activity, and column Q tells how much money will be required to accomplish each activity. By transferring this information to the Grants Office Time Line (Figure 7.5), your proposal developers will have a fairly accurate estimate of their cash flow needs. Some public and private grantors will accept cash forecasts as an adequate expenditure plan and will provide payment in advance, thus minimizing your district's cash investment.

Grants Office Time Line

The Grants Office Time Line is a visual representation of the proposal's time frame. It also shows an estimate of the cash required to stay on schedule.

From the Project Planner, transfer your activity number to column 1 of the Time Line. Then draw a line from the activity's projected start date to its completion date. For example, if the activity is to begin in the second month of the project and end in the fourth month, draw a line from 2 to 4.

On the far right of the line, write the total cost of the activity from column Q of the Project Planner.

Federal and many state funders require a quarterly cash forecast. In these cases, place the estimated cash forecast in the appropriate quarterly column at the bottom of the Time Line. Estimate the total cash needed for those activities that take place over several quarters or that require advance expenditure, such as equipment purchase.

Your proposal developers will benefit from a booklet on how to create a grant-winning plan. This booklet should include samples of completed project planners tailored to your district along with the federal budget pages that reflect the column totals from the project planners. The booklet should also include instructions on how your district grants office can help grantseekers obtain copies of funded proposals to serve as models.

The subsequent chapters help you move from the Project Planner spreadsheet to the written proposal.