Chapter 11

Administering Federal and Private Grant Funds

THE PREVIOUS CHAPTERS outline the broader responsibilities and challenges that the district grants office must deal with to help their schools attract more grant funding. But many such offices are not yet involved in preproposal contact, developing linkages, or other techniques for increasing grants success. Administrators from these offices perhaps view themselves as fiscal agents, accountants, or bookkeepers responsible for administering grant funds. Although the fiscal functions of a grants office are critical to a district's eligibility for grants, the office should have other responsibilities as well.

It should be the gatekeeper between the district's grantseekers and potential grantors, because even one error in communication between the two can result in the immediate rejection of a proposal.

The proposal writer, in some ways, is like a child waiting all year for his birthday. He wants to know what he'll get, and he wants to know now! So before your proposal writers call to see what they might be getting later, it is imperative that you give them explicit instructions about contacting grantors when a proposal is still in play.

Federal Grantor Contact After Proposal Submission

Once your school's proposal has been logged by a federal grantor, it is considered to be in submission. During this time it will be assigned to a review panel and spend several months in the review process.

To put it bluntly, a federal agency will consider contact by you or your grantseekers during this time as an attempt to unfairly influence the review and outcome. So contact with the funder should be made only on the rare occasion when further information should have an impact on its decision, as when one of the following is the case:

- A new advance in education allows you to drastically cut the grant amount requested (because of new equipment, software, assessment tools, or the like)

- Another grantor has agreed to partially fund the project, so you need less money

- You need to pull your school's proposal from submission because another funding source has decided to fund it totally

Short of these or other dramatic reasons, instruct your grantseekers to avoid contact with the grantor while their proposal is being reviewed.

There is a healthy sense of paranoia in Washington concerning the peer-review process; in fact, congressional involvement in the grants award process has been investigated several times by federal watchdog agencies. Grant awards are supposed to be determined by peer review that is based solely on published selection criteria and therefore removed from political intervention. To avoid any problems, just remember that contact by elected officials on your behalf or by your grantseekers while their proposal is in submission could be viewed as an attempt to influence or subvert the review process, which could result in the disqualification of your proposal.

Foundation or Corporate Grantor Contact After Proposal Submission

Contact with federal bureaucrats may be a legal issue during this period; with corporate and foundation grantors it may be an ethical issue. Considering how few grant-related employees most private grantors have, contacting them may also be difficult. The situations in which contact with foundation and corporate grantors are allowed should basically be the same as with federal grantors. Significant changes in the requested amount should be forwarded in writing to the grantor with a brief but thorough explanation of what has occurred and how it will modify your proposal. Significant changes in a proposal should be relatively rare.

Any contact aimed at influencing the proposal outcome should be through the linkage your district has to the grantor's staff or board members. It's okay to tell your contacts or links that you submitted a proposal; indeed, your grants office should forward a copy of the submitted proposal to them with a note of thanks for the help. They may then mention the submitted proposal to other board members as they golf or dine, or speak on your behalf when the proposal comes up for review. The choice of if, when, and how to act is up to them—but they must know of your submittal first.

Dealing with Rejection or Acceptance

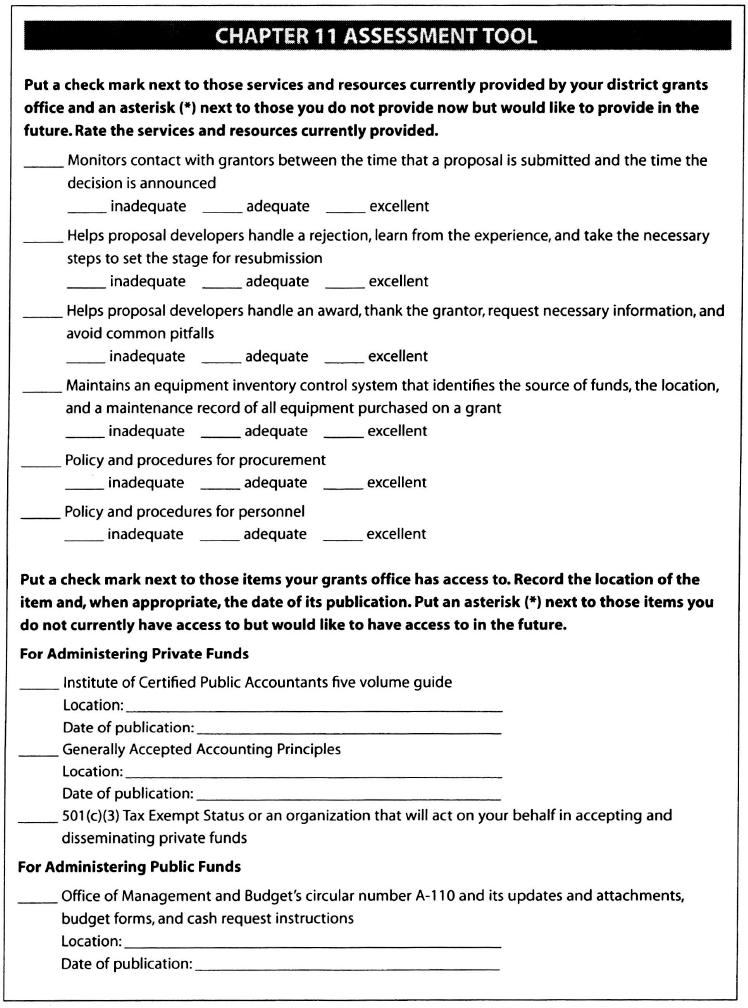

Dealing with proposal outcomes is a good topic for one or more booklets (see Chapter Two), the information in which could also be placed on your website. These booklets should outline the steps proposal developers must take when their proposal is rejected or awarded by public or private grantors. Don't overload and frustrate your grantseekers by giving them federal guidelines and a myriad of assurances that must be complied with before their grants are awarded. They will respond much more favorably to a short, well-written booklet that summarizes the information they need. Build your grants system from the point of view of the grantee and the grantor. Ask how much the grantee needs to know about grant rules and regulations and how much assistance your office can provide. What would you require and feel comfortable with if it were your money and you were the grantor?

Trying to develop an inclusive grants document, some districts have developed a manual with hundreds of pages of forms, rules, and detailed procedures. This is too much.

Rejected grantseekers need encouragement. A short booklet on what to do when a proposal is rejected should deal with the rejection in an educational and problem-solving manner. In addition, coordinating your grantseekers' response to rejection can enhance your district's image with the grantor and increase your chances for future funding.

A similar document on what to do when a proposal is awarded will enhance your office's working relationship with your grantseekers and with the grantor. The booklet should clearly define everyone's role: grantee, grantor, and grant administrator. All want to get good projects under way, but getting off on the right foot is best for everyone.

Basically, two district grants administration systems must be dealt with, private and public.

Private Grantors

Private grantors do not require as many forms or operate under as many rules as their government counterparts. But they do expect that the funds they grant will be handled in a businesslike manner.

Rejected Proposals

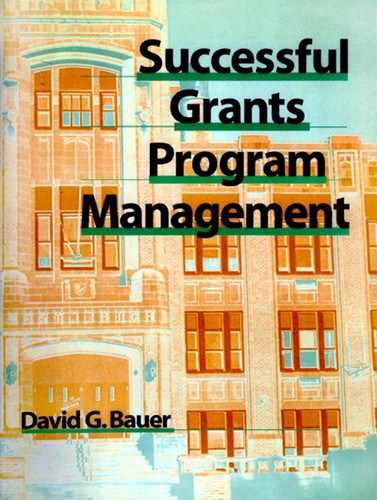

What is the district grants office's role when the private grantor rejects the proposal? Disgruntled grantseekers want to put the disappointment behind them and generally forget to send or e-mail a thank you letter. Therefore, your office should take a lead role in helping unsuccessful grantseekers continue the process by suggesting that they do so. It will have little or no bearing on the rejected proposal, but may have significant impact on the outcome of resubmittal or new submittal. Review the Sample thank you Letter if Rejected by a Foundation or Corporation (Figure 11.1). The purpose of this note or letter is to thank the funding source for investing time in reviewing your proposal and to advise them of your intentions to reapply. The letter could also ask why the proposal was rejected. Most private grantors won't respond, but by asking you demonstrate that your district wants to learn all it can from the rejection.

Awarded Proposals

Your district grants office's role in the proper administration of a grant award begins with the recognition of the award and continues through to completion of the project and the submittal of evaluation and closeout forms. All contact with the grantor should flow through that office. A thank you should be sent as soon as the amount of the award is established and agreed upon by both the grantor and the district. The thank you letter should be signed by your highest-ranking district administrator or another person deemed most credible by the grantor. It could be the school board president, the principal, a volunteer, a linkage, or even a corporate employee who is a volunteer in your district. The letter could be jointly signed by an administrator and a volunteer.

The thank you letter should request information on the transfer of funds to the district, special payment procedures or schedules, and any preferences of the grantor concerning public relations or news releases (see Figure 11.2).

Acceptance of funds by a school district can pose problems for some foundations. Many stipulate that their awards can be received only by nonprofits that have a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status or equivalent from the IRS. Foundations prefer this so that fiscal responsibility rests with the recipient of the award.

Your district is a nonprofit but may not have 501(c)(3) status. If your district does not have a school foundation or other 501(c)(3)-designated group, you may need to request that your award be given to a 501(c)(3) that will process the grant on your district's behalf. For example, you could use your local community foundation or a 501(c)(3)-designated education or youth group in your area to act on your behalf in accepting and disseminating the funds.

Ultimately you should set up your own school foundation. David G. Bauer Associates can provide your district with information on setting up a school foundation and a list of consultants who specialize in this field (see information at end of book).

Most foundations, corporations, and fraternal and social groups expect that your grants administration system will follow the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) guidelines on record keeping. For more information contact AICPA, 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10036-8775, (212) 596-6200. Its website is http://www.aicpa.org/

When it comes to budget changes and closeout, it is difficult to receive written approval for budget reallocation from all but the largest of foundations and corporations. Ninety percent of private grantors meet only one or two times per year and are focused on reading and acting on new proposals. If you wait for permission to reallocate funds between budget categories, you may never receive a notice of approval or it will arrive after the grant is completed. Because foundations make grants from a trust or fund and must, by IRS rules, grant at least 5 percent of the value of their assets each year, you will create problems if your school district returns unused funds from the previous year. One approach is to notify the grantor that your office will be transferring funds from one budget category to another in thirty days unless you receive notification to the contrary.

Private grantors expect you to follow your district's normal business procedures for contracting, bidding, purchase, maintenance, and inventory of equipment. Your district grants office should have an inventory control system that identifies the source of funds, the location, and the maintenance records of all equipment purchased on a grant.

Public Grantors

Federal and state funding requirements are not nearly as exasperating as some make them out to be. The guidelines and regulations are quite clear and reasonable when you consider that the rules are meant to safeguard tax dollars. The federal bureaucrats that you made preproposal contact with are generally very helpful and when approached correctly will assist your efforts to operate an effective and responsible grants administration system.

Rejected Proposals

What can the district grants office do when a federal or state proposal is rejected? Help grantseekers learn as much as possible from the experience. Toward this end, send a thank you letter requesting information on the scores and comments of the reviewers. This will help your grantseekers learn what they did that was correct and what could have been better. As the district grants administrator, you are in a good position to discuss the comments and scores with the federal or state program official because you are not ego-involved in the proposal and can accept and use the information provided to help your grantseekers improve the proposal for resubmission. You position your school district in a positive manner by thanking the official for her or his time during preproposal contact, for any materials provided, and for the effort of the staff involved in the evaluation process.

Even if the federal or state agency sends the reviewers' comments without your requesting them, a thank you letter is still in order. You can tailor the sample letter in Figure 11.3 to your system. (Although this letter is for federal funding sources, note that it can be adapted to state funding sources as well.)

Awarded Proposals

As previously mentioned, it is good policy to inform your grantseekers that contact with the grantor after their proposal has been submitted can seriously jeopardize the proposal's outcome. Based on your grantseekers' research and preproposal contact, you may have an idea of when the proposal outcome will be announced. If so, you can contact your congressperson's office to alert him or her to a possible upcoming announcement of a federal grant award to your district. Be certain your congressperson knows you do not want or expect him or her to contact or pressure the agency concerning your proposal. Your purpose is to alert him or her regarding the expected decision and to coordinate the announcement of funding. This is a valuable opportunity to use the grants mechanism to alert the public to your district's efforts to obtain resources from outside the district.

Ask your congressperson to contact your district grants office if and when he or she is informed of your award. All federal applications require identification of the applicant's congressional district. When a proposal is selected for funding, the system is designed to notify the congressperson's office—often before notifying the grantee. You may even read about your award in the newspaper before you receive official notice. If your congressperson informs you of the award, suggest that the congressional office and your district superintendent's office develop a joint public relations release to the media.

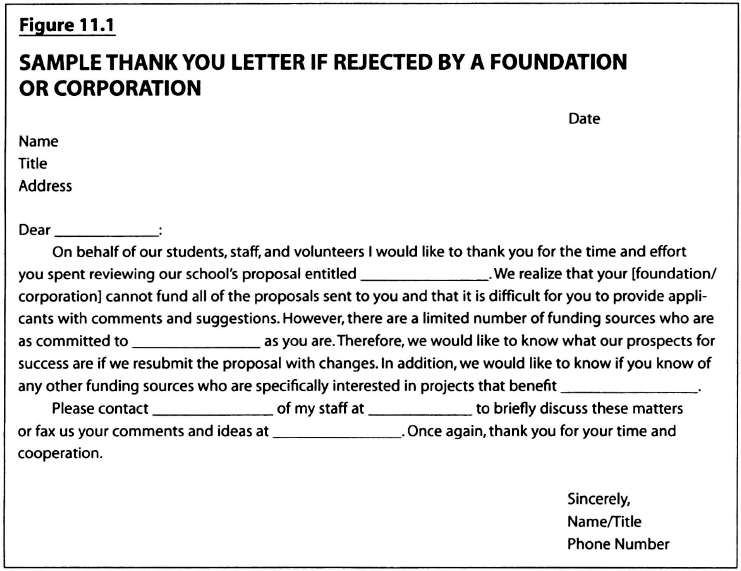

Whether or not your district grants office takes this opportunity to work with your congressperson, your office should lead the way in submitting a thank you letter to the grantor. The letter should include requests for reviewers' comments (your grantseekers want to learn what they did correctly and what they could have done better), procedures for instituting a grant payment plan, forms that will be necessary for periodic reports, and a completed address label to use in returning the requested information.

Your thank you letter should also acknowledge the grantor's work in reviewing the proposal and contain an invitation to visit the district. Tailor the sample letter in Figure 11.4 to your system. (Although this sample letter is for federal funding sources, note that it can be adapted to state funding sources as well.)

The requirements you now face about record keeping, budget changes, cash requests, equipment, and inventory control are all covered in the Office of Management and Budget's circular A-110. This circular is entitled “Uniform Administrative Requirements for Grants and Agreements with Institutions of Higher Education, Hospitals, and Other Nonprofit Organizations.” The twenty-six-page circular, with its updates, budget forms, and cash request instructions, is your guide to federal rules regarding your district's grant. Available from the U.S. Government Printing Office—Superintendent of Documents, or on the Internet at http://www.doleta.gov/regs/omb/index.htm, the circular covers pre-award requirements, post-award requirements, after-the-award requirements, and contract provisions in an appendix.

The following is a summary of the information contained in the circular. Refer to the most current circular for specific information on each of the sections within each of the subparts:

- Subpart A—General: Purpose, definitions, effect on other issuances, deviations, subawards

- Subpart B—Pre-Award Requirements: Purpose, pre-award policies, forms for applying for federal assistance, debarment and suspension, special award conditions, metric system of measurement, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, certifications and representations

- Subpart C—Postaward Requirements:

Financial and Program Management—purpose of financial and program management, standards for financial management systems, payment, cost sharing or matching, program income, revision of budget and program plans, nonfederal audits, allowable costs, period of availability of funds, conditional exceptions

Property Standards—purpose of property standards, insurance coverage, real property, federally owned and exempt property, equipment, supplies and other expendable property, intangible property, property trust relationship

Procurement Standards—purpose of procurement standards, recipient responsibilities, codes of conduct, competition, procurement procedures, cost and price analysis, procurement records, contract administration, contract provisions

Report and Records—purpose of report and records, monitoring and reporting program performance, financial reporting, retention and access requirements for records

Termination and Enforcement—purpose of termination and enforcement, termination, enforcement

- Subpart D—After-the-Award Requirements: Purpose, closeout procedures, subsequent adjustments and continuing responsibilities, collection of amounts due

- Appendix A—Contract Provisions

When you consider that most of your district's requirements are equal to those called for under the government circulars, federal grant funds should not instill fear and trepidation in your district.

Most grants administrators' problems occur when their business office is involved in controlling purchase orders and bidding contracts. The business office may follow federal guidelines, but their purchase orders may not be seen by your grants office, and even though the correct procedure is followed the project director of the grant may purchase items not called for in the proposal. The business officers' responsibility is to make sure that there are funds available under the budget category and to bid out the purchase, not to look at the proposal's objectives and methods and question the project director relative to changes in purchase.

Similar problems occur when the grants office is not involved directly in personnel transactions. Even when the district personnel office follows federal guidelines for hiring, without a direct link to the grants office and to the functions that the proposed grant employee will perform, some project directors may abuse the system and hire inappropriate grant personnel.

In an effort to lower the payroll for central administration, some districts reduce the number of grants administration staff. The need may be real, but the district's ability to attract outside resources is directly related to the quality of its grants administration system. Therefore, districts that reduce the staff and the administrative functions performed by their grants office risk not only their credibility but also their access to future funds.

In addition, an inefficient grants administration system can mean the loss of funds intended to reimburse the grantee for costs of carrying out projects that are difficult to charge directly to the grant. These indirect costs include those needed to provide classrooms, office space, security, restrooms, payroll, personnel support, and so on. Although these reimbursable costs clearly play a critical role in supporting a district, they can be overlooked or undercharged if a district does not have a diligent, knowledgeable grants administration staff.

For example, many school districts are aware of their indirect cost rate for restricted federal programs (the restricted cost rate) but unaware of their rate for unrestricted federal programs (the unrestricted cost rate). Districts that find themselves in this predicament often apply their restricted rate to all federal grant programs, even programs that allow them to use the unrestricted rate. In one school district I worked with, the grants administration staff was unaware of the district's unrestricted rate, so it applied the 2 percent restricted rate to all federal grants. With a little work, I was able to negotiate an unrestricted rate of 26 percent, which resulted in $25,000 more in reimbursed indirect costs from just one grant!

As you can see, the decentralized grants program exposes the school district to oversights as well as to legal and ethical problems. Even the most well-intentioned and ethical project director needs a system of checks and balances, which the grants office can provide.