Chapter eight. Formulating the Mess1

1“Formulating the mess” and “idealized design” are synonymous with the name Ackoff. However those of us who associated with him long enough have formulated messes and produced idealized designs so many times that each has, inevitably, come to develop a unique version of his/her own.

In a nutshell, systems thinking is about defining problems and designing solutions in an environment characterized by chaos and complexity. According to Ackoff: “We fail more often not because we fail to solve the problem we face but because we fail to face the right problem.”

Unfortunately, today we are not confronted with a single problem but a system of problems, or in reality a “mess,” and defining this mess is the most important step in confronting our current challenges.

We formulate the mess to create a shared understanding of the underlying interdependencies, assumptions, values, and reinforcing reward system that are responsible for regenerating the problematic patterns repeatedly.

A mess is neither an aberration nor a prediction. It is the future implicit in the present behavior of the system. Mess is the consequence of the system's current state of affairs. In formulating the mess we are more concerned with the dynamics and not static analysis. Not only do we need to learn what is wrong, but we need to know how we got there and why a system behaves the way it does.

Keywords: Alienation; Corruption; Coupling/de-coupling; Drivers for change; Early-warning system; Insecurity; Maldistribution; Mediocrity; Obstruction analysis; Polarization; Risk and vulnerability; Scarcity; Stock market capitalism; Structural conflict; Systems analysis; Systems dynamics; Terrorism; Tolerance of incompetence

We fail more often not because we fail to solve the problem we face but because we fail to face the right problem.

R.L. Ackoff

The obstructions that prevent a system from facing its current reality are self-imposed. Hidden and out of reach, they reside at the core of our perceptions and find expression in mental models, assumptions, and images. These obstructions essentially set us up, shape our world, and chart our future. They are responsible for preserving the system as it is and frustrate its efforts to become what it can be.

The mess is formulated to achieve the following aims:

• Understand the underlying assumptions and reinforcing operations responsible for regenerating the problematic pattern repeatedly

• Develop a shared understanding of why the system behaves the way it does and generate a shared understanding about the nature of the current reality among the major actors

• Minimize the resistance to change and maximize the courage to act by making the real enemy explicitly visible and believable

• Identify the areas of greatest leverage, vulnerability, and/or possible seeds of the system's destruction

Formulating the mess is to map the dynamic behavior of a system. It is to capture the iterative nature of the multiple feedback loops by demonstrating the nature of interdependencies in the system. It is the future implicit in the present behavior of the system, the consequence of the system's current state of affairs. The essence of the mess is the systemic nature of the situation. Parts are coproducers of one another. Improvement of one part without considering the reinforcing impact of the feedback loops on it will not be effective. Messes are very resilient; they have a way of regenerating themselves. It is this quality that makes a mess an intractable phenomenon. The prevalent powerlessness and impotency in dealing with the mess lead to the inevitable denial on which messes thrive.

Formulation of the mess is a three-phase process of

1. Searching

2. Mapping

3. Telling the story2

2I have adopted this classification on the suggestion of my old friend and colleague John Pourdehnad. Look for a more elaborate classification in J. Pourdehnad (1992).

8.1. Searching

Searching is the iterative examination that generates information, knowledge, and understanding about the system and its environment. It is about watching how a system actually behaves, learning its history, and understanding why it does what it does. The search phase of mess formulation involves three kinds of inquiry:

1. Systems analysis

2. Obstruction analysis

3. System dynamics

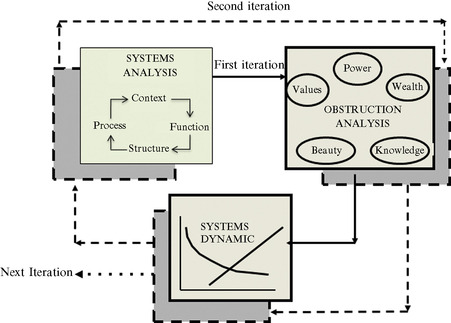

The three inquiries evolve iteratively (Figure 8.1). With each successive cycle of iterations, we try to achieve a higher level of specificity. In the first iteration we try to get a feel for the whole; define the system boundary; identify important variables; note areas of consensus and conflict; and identify gaps in information, knowledge, and understanding. Between iterations, we try to fill in the gaps. In subsequent iterations, we verify the assertions made in the previous iteration; obtain agreement on significant issues; and develop an interactive model to understand the behavior of the system.

8.1.1. Systems Analysis

Systems analysis is used to develop a snapshot of the current system and its environment that describes their structural, functional, and behavioral aspects without making a value judgment (see Table 8.1).

8.1.2. Obstruction Analysis

Obstruction analysis is used to identify the malfunctioning in the power, knowledge, wealth, beauty, and value dimensions of a social system (see Table 8.2).

Scarcity, maldistribution, and insecurity in any of the five dimensions represent what we have called first-degree obstructions and their reinforcing interactions produce second-order obstructions as discussed in Chapter 4: polarization, alienation, corruption, and terrorism.

8.1.3. System Dynamics

System dynamics is about dynamic, not static, analysis. It is not only about learning what is wrong but also about how we got there. This includes searching for the why question: why the system behaves the way it does. This requires understanding the nature of multi-loop feedback systems and interactions of interdependent variables in the context of time (see Table 8.3). The trick is to capture the complexity produced by the cumulative effect of repeated actions. For example double-digit growth, for a short period of time, not only may be desirable but also in all likelihood might not produce many negative concerns. However, repeating double-digit growth for a long period of time is not only a formidable challenge, but it would also have many negative and undesirable consequences.

Table 8.1, Table 8.2 and Table 8.3 are to be used only as guides or examples of the types of questions that may be examined in the search process. Use them if you find them to be useful for the specific case or context you are considering, but do not let the forms take over the content. Trust your intuition. Think about purposefulness, multidimensionality, and counterintuitive behavior. Remember, this is an iterative process. Avoid getting lost in the jungle of information. Start by looking from 30,000 feet above, and then generate enough information to establish the relevancy of each variable under consideration.

In a search process, time is an important consideration. The available time defines the level of generality and the degree of specificity that can be achieved. However, the available time should be allocated to each part of the inquiry to permit a pass through the cycle at least twice to understand, at a minimum, the holistic nature of the situation and identify the significant elements of the mess.

Having completed the first iteration of systems analysis, obstruction analysis, and system dynamics, we must pause to make sense of what we have already learned. We need to make explicit assumptions about the set of critical drivers and major events and their relationships to be able to develop a tentative picture of the whole. Subsequent iterations will clarify, verify, and/or modify this picture. But we use this picture initially to develop a guideline of what we need to know in more detail in further iterations.

8.2. Mapping the mess

The search phase usually identifies a large number of issues, obstructions, and drivers. To make sense of these findings, we have to synthesize them into a few categories so we can examine their interactions and understand the essence of the mess.

The process involves grouping various phenomena into categories or subsets, then identifying themes, each of which is the emergent property of its constituent elements (members of subsets).

Generation of these themes usually requires an interactive discussion to achieve a shared understanding of the grouping criteria. Each theme should be (1) defined clearly so there is no confusion about what it represents and (2) substantiated in terms of its prevalence. Themes should not reflect isolated occurrences. A litmus test for the validity of the themes is that, when presented to relevant stakeholders, a clear sign of recognition results (an “aha” experience).

Finally, after all relevant themes are identified and substantiated, the relationships (interactions) among the elements must be addressed.

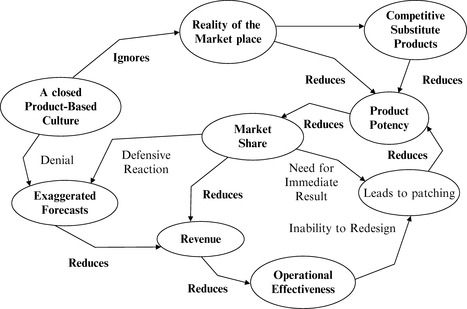

Each theme is normally a mini mess in its own right; however, for the purpose of studying the interactions, we would initially treat each theme as a self-containing whole. In subsequent iterations, if a theme were to emerge as the central concern we would break it down further into smaller components so their interactions with the other elements of the mess could be properly represented. Developing pictorial representations of the interactions among themes is essential to capture the interdependency and holistic nature of the mess. 3Figure 8.2 is an example of such a representation, one in which the following themes have been identified:

3Peter Checkland (1981) uses a similar method of mapping to capture “the shape of systems movement.”

• A closed product division culture

• Technological change in the market niche

• Product potency

• Operational effectiveness

• Exaggerated forecast

• Patching

This type of diagram can be constructed and read by tracing numbers on the graph and the lines of interactions as follows.

As a substitute product gradually gains acceptance, a gradual loss of product potency results in decreased market demand. In a closed divisional culture, the identity of any division is defined by the viability of its market niche. Any threat to this niche constitutes a threat to that division. Therefore, the first reaction to this unpleasant reality is denial. The division, to protect itself, repeatedly issues exaggerated forecasts, which prove false and damage its credibility. This increases the pressure to improve sales by reducing cost at any cost. But the change in the marketplace demands a redesign to improve product potency. Meanwhile, pressure to produce immediate results encourages short-term remedies. An ineffective operational system, under this pressure, is not capable of redesigning the product, so it patches minor changes onto the existing product. This further increases the cost, reducing the sales and, most unfortunately, granting precious time to the competition to solidify its position. The vicious circle thus continues.

Once the elements of the mess and their interactions are mapped, it will be easy to see why and how the current mess has evolved. The above mess, unfortunately, is a well-known phenomenon that is produced whenever a successful product division misses a technological break relevant to its field. As put beautifully by Watson Jr., unfortunately “Probability of missing a technological break is directly proportional to the level of success the organization had achieved in the previous technology.”

Mapping the mess is the heuristic process of defining essential characteristics and the emergent property of the mess. It involves finding the “second-order machine” residing within the system. This unanticipated consequence of the existing order produces paralyzing “type II” properties that create inertia, prevent change, and frustrate attempts to make significant improvements. To achieve an order-of-magnitude improvement in any system's performance, the second-order machine has to be recognized and dismantled. Exaggeration of the winning formula, combined with a possible change of game, faulty measurement, and reward system more often than not will point to a set of seemingly innocent, simple, but deep-rooted assumptions that are at the core of the second-order machine.

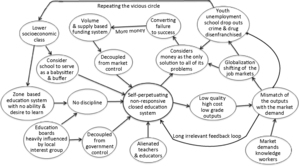

Figure 8.3 attempts to map the mess of the public education system. Although produced specifically for a given state, it captures the generality of how the system has been uncoupled from both market and government control, and how it has been able to convert its undeniable failure into success by exploiting the false assumption that money can solve all shortcomings in education.

8.3. Telling the story

Mess is not a prediction; it is an early warning system. Proper packaging and communicating of the message is as important as the content of the message itself. Formulating and disseminating the mess is a significant step toward solving it. More often than not, knowledge of the mess helps dissolve it. A believable and compelling story that reveals the undesirable future implicit in the current state has to be developed. Assume that things will go wrong, if they can, all at the same time. Try to produce a resonance and show how a system breakdown can occur. The challenge is to create a believable shared understanding of the current reality and its undesirable consequences, thus creating a desire for change. The story should consider the stake, influence, and interest of the relevant stakeholders. It should not assess blame or make people defensive. The mess should be presented as a consequence of past success, not as a result of failure. Remember, the world is not run by those who are right; it is run by those who can convince others that they are right.

Generally, there seems reluctance on management's part to share the mess with other stakeholders, especially the members, under the pretext that this might discourage them. Not only does this practice defeat the purpose of formulating the mess, but it is also counterintuitive. It has been my experience that members of an organization, more often than not, are aware of the nature of the mess; in most cases they are simply not allowed to talk about it, or they might not be able to articulate it as completely as during the formulation of the mess. What they really do not know is whether management is aware of the mess or not. Usually, sharing the mess brings a sigh of relief and a willingness to confront it.

8.3.1. Formulating the Mess: A Case Review (Story of Utility Industry)

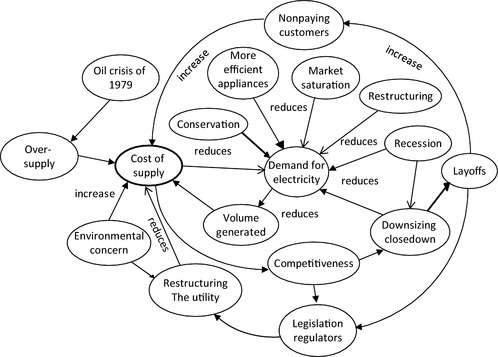

This section is a sample of a real mess formulation. It represents the mess of the utility industry during the early 1990s.

Figure 8.4 represents the context of the utility industry where the oil crisis of 1979 had created a mindset of insecurity. This mindset resulted in a double jeopardy of over-supply of power generation combined with policies that reduced demand. Counterintuitively in a fixed cost regulated environment this combination resulted in a higher per unit cost of electricity leading to a vicious circle of reduced competitiveness, downsizing, recession, layoffs, and an increasing number of nonpaying customers, thus adding to cost of supply and pressure to restructure the industry.

XYZ is a name of a fictitious corporation reflecting a typical utility company at the time. I am sure many will easily identify with it.

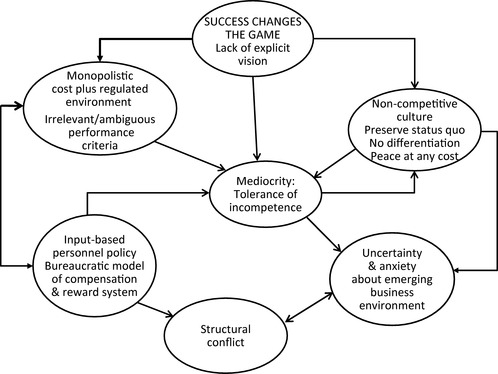

Mapping the mess of the XYZ Corporation followed the stated iterative process. It involved observing how the system behaved, understanding its history, and appreciating why it does what it does. We identified sets of internal and external behavior that coproduce the mess. These behaviors were categorized around major themes. Generation of the themes involved extensive discussions so a shared understanding of the grouping criteria was achieved.

Each theme, therefore, symbolically represents a complex set of behaviors reflecting the collective subjectivity of the mess team. The critical elements of the mess include:

1. Success changes the game, lack of explicit vision

2. The monopolistic, cost plus environment

3. The non-competitive culture

4. Mediocrity, tolerance of incompetence

5. The input-based personnel policy

6. Structural incompatibility and conflict

7. Uncertainty about the future

But the critical step was to produce a graphical representation of the interactions and reinforcing impact of each element of the mess on the whole. Recall that elements of the mess all happen at the same time. They are not represented properly by written language, which naturally is sequential and linear. The pattern of interactions among the themes is developed and pictorially represented (Figure 8.5). A deliberate effort was made to provide in-depth explanations as to why the system behaves the way it does and what was responsible for this behavior.

The initial investigation indicated that the source of XYZ mess is not significantly separate from the overall mess of the industry to which it belongs. It also became equally apparent that the emergent mess is so profound and overpowering that it warrants an in-depth understanding of it. Mess, as was pointed out, is highly interrelated. It is a system-wide phenomenon. No part of a mess can be dealt with independently of other elements. Messes, therefore, cannot be dissolved partially or locally. No sooner is an element of a mess removed than the remaining parts regenerate it. This explains why, despite recent management's best efforts, the mess has not gone away. Mess is an exaggeration. It is a deliberate concentration on major obstructions that intensifies the system's rigid lock into a specific context. The idea is that awareness of the mess is the precondition to its dissolution. Once we know where the long-term consequences of our actions are taking us, we are likely to make the commitment to take the necessary measures and act preventively. The systemic properties of the mess are the unintended consequence of the past success. Mess is the legacy of the old game. Given the general context of the regulated utilities, it is only natural that the mess is more or less typical of the industry as a whole. The mess is XYZ's long-term adaptation to a long-secured context. Had the advent of deregulation not rendered the erstwhile context of utilities obsolete, the mess would not have been considered a mess. It would still be regarded as an adequate adaptive response to an uncontrollable dominant environment. It is the mismatch between the existing culture and the new challenges that is fraught with unintended (i.e., catastrophic) consequences. Therein lies the age-old lesson behind the rise and fall of man-made institutions: success changes the game and converts, by default, the very secrets of success to the ultimate seeds of destruction.

The mess of XYZ is the product of an exaggerated imbalance: excessive attention to a particular aspect of the system (cost plus, input-based, friction-free, variety-reducing, and stability-oriented characteristics) and extreme neglect of the others (performance-based, entrepreneurial, market-driven, change-oriented, and variety-amplifying characteristics). Suboptimization, given enough time, has made virtual evils out of proven virtues. Under the circumstances to achieve an order-of-magnitude improvement in the performance of XYZ requires that this second-order machine be recognized and dismantled. Understanding the mess, therefore, provides XYZ with a powerful tool to realize its transformation effort.

8.3.2. Success Changes the Game, Lack of Explicit Vision

The utility system of America, despite whatever self-criticism is leveled at it, was the envy of the world. To have covered and provided for the insatiable energy needs of a vast continent in a span of a few decades could not have been achieved without gigantic vision, phenomenal leadership, and Herculean effort. Even today, a comparable achievement would be a daunting challenge to other industrial societies, even in terms of internal technical consistency and operational reliability, let alone the sheer scale. In America the utilities used to be looked up to as icons of modern management. They were not waiting for rate increases to be granted. Efficiencies kept pushing costs down. But with success came complacency. The system stopped developing since it was pointless to improve a system that was already perfect. Therefore, feeling no need for any new sources of variety, utilities closed their gene pool, exclusively dealing with the insiders to the industry.

As a consequence, strategic thinking became a casualty of

• A retroactive pride in the past

• A shift of focus from new discoveries and frontiers to safeguarding what has already been achieved

• Crisis management, the organization operating in a reactive mode responding only to problems as they emerge

• Erosion of core competence

An annual planning process identified as strategic planning is performed. The plans generated are in effect operating plans that evolve into “to-do” lists for the upcoming year. Lack of an articulated strategy has caused XYZ to forego new business opportunities. In the absence of a new vision for a more exciting future, the system engages in a constant struggle to preserve the old, a nostalgic preoccupation with the rear-view mirror.

8.3.3. Monopolistic, Cost Plus, Regulated Environment

The nature of XYZ is defined by its exclusive franchise operating in a cost plus regulated environment. No other single factor has been more responsible for influencing the nature of XYZ — being what it is, and behaving the way it does.

Utility regulations were originally established to correct the utility industry's abusive business practices, restore public confidence in the monopolistic system, and serve as a proxy for competition. Once the industry's abuses were curbed, rate making evolved into the validation process in a cost plus system. The cost plus environment performed reasonably well in the post-war era, and even more so in the 1960s, as new, less expensive energy sources were developed and rate decreases became the industry norm. Price decreases fueled an expanding economy, stimulated customer demand and elevated the industry's stature, and added value to shareholder investments. However, the 1970s ushered in shortages, embargoes, high inflation, record interest rates, environmental regulations, and the “China Syndrome,” all of which propelled costs and the industry into a more contentious relationship with customers and environmentalists. In response to higher prices, environmental concerns, and public pressures, regulators implemented “social justice” into rate design and regulation. During the 1980s, environmentalists and self-interest groups used the regulatory arena to promote conservation programs, force even further social justice into rate designs, and promulgate rules designed to displace the electric industry from its traditional role of plant builder, owner, and operator. In the cost plus regulated environment, the regulator looms omnipotent. What it does overrides almost every other source of influence in the operation of a utility company. The necessity to cope with the regulated environment has led to a bureaucratic competency in the form of an ability to manage costs and allocation techniques to the best advantage of the system. The cost allocation skills, perfected to an art form, then shape all operating policies, procedures, and processes. This context leads to ambiguous and irrelevant performance criteria. Typical business measures are usually disregarded in lieu of a cost plus regulatory environment. For example, the ill-defined social and economic agenda defies the establishment of meaningful performance measures. In a sound competitive environment, for example, it would simply be dismissed as facetious to expect that a company should not only reduce the demand for its output but also at the same time pick up the tab for it. Once the survival of the system becomes independent of its performance, the luxury of operating in a cost plus third-party payer environment leads to the emergence of a totally new game with its own unique ground rules and motivational consequences. People realize over time that they can afford to ignore the early warnings and to look up to the regulator as the main source of their viability with a limited concern for the effectiveness of the organization and the discipline of a real marketplace.

The cost plus system is terminally ill. The customer base resents it, and the political machine will surely demand its demise. While the future model for rate regulation and the industry as a whole has yet to be designed, it is clear that a new industry leader or set of standards will emerge for others to follow. Any new performance standards will probably draw heavily from the competitive model and will, at least initially, favor cost efficiency initiatives and reward creative entrepreneurial efforts.

8.3.4. The Non-Competitive Culture

The organizational culture of XYZ, influenced by a cost plus regulatory environment, is characterized by the following attributes:

• Non-competitively regulated environment conducive to peaceful coexistence of peers

• Mutual respect of players for well-established and sacrosanct territories

• A mainstream tendency to comply with the law of averages; a bias toward being similar and non-threatening among like-minded peers as opposed to being differentiated and distinct from the other utilities

• A time-honored respect for such communal values as stability, harmony, and camaraderie over competency

• A habitual expectation of taking for granted guaranteed earnings and continued growth

• An unspoken assumption that the survival of the system is independent of the efficiency of its operation

• Looking up to “regulators” as the single source of change, albeit a benign one

• Considering the regulator as the real customer, who determines the future, instead of the end user who has no choice

• Determining the inputs (size of personnel, years of education, length of seniority, etc.) instead of the outputs (innovations, productivity, performance, etc.) as the basis of status and benefits; change is perceived as a threat to hard-won security and status

• A much greater sensitivity to errors of commission as opposed to errors of omission, an implicit denial of the fact that organizations fail more often not because of what they do but because of what they do not do

• The need for power overriding the need for achievement: status and membership are enhanced more by patronage and loyalty than competitive behavior (who you know is as important as what you produce)

• Not recognizing the significance of vital talent and relevant technology

• Formation of identities around the closely guarded turfs, rather than the whole, which is conveniently ignored

• The unities of command being the overriding vehicle to manage conflict, remove confusion, create alignment, and correct deviation

• Considering the superior–subordinate relationship as the only building block of the organization, leading to hierarchical one-dimensional structure

8.3.5. The Input-Based Personnel Policy

The compensation and reward system of XYZ is based on a mechanistic model. This model was originally created in response to strong unions' demands for social justice, fairness, and security for workers in large industrial concerns. The conventional model is still dominant in a majority of manufacturing environments. Notwithstanding the obvious flaws of the conventional model, the competitive nature of these industries produces a balancing effect, which makes the model workable despite its vital shortcomings. Unfortunately, however, in cost plus non-competitive environments, the model brings out the worst of protected bureaucracies. At XYZ, the model's absence of clear performance measures has become a major obstruction. It has become an integral part of the second-order machine that determines the essential character of XYZ and makes it behave the way it does. For instance, marginal performers can receive favorable reviews and remain with XYZ for many years. To compensate for the consequential underperformance, additional personnel are then utilized to accomplish the designated work assignments. Personnel policy, once in place, takes a life of its own. No aspect of the organization is too hypersensitive to redesign; therefore it is no accident that the conventional compensation system has long endured as a default value despite its crippling effects. The following summarizes the characteristics of the conventional compensation system of XYZ. As pointed out, these manifestations are not unique. They are shared by many organizations that have adopted the traditional model. The existing system is characterized by “job” evaluation. It is the job and not the occupant that is the focus of evaluation. Fixed or base pay is determined by the job content and the qualifications derived from it. Different people having the same job get essentially the same pay. The system reflects the motto that constitutes this mechanical notion of fairness, that is, “equal pay for equal job.” The system avoids differentiating people based on the differences that make a difference. The overriding concern seems to be with stability and ease of measurement. Since average performers constitute the commanding majority of employees, it is therefore believed that compensation based on the typical average performer produces less dissatisfaction, and results in a more stable work environment. The system is selectively geared to the features that are common to all jobs. The real occupant is deliberately ignored. It is implied that considering the occupant's unique talents, skills, and interests as well as performance and contributions would involve personalities, intangibles, complexities, and subjective judgments. It is, therefore, imperative to deliberately insulate the process of evaluation from individual judgment “no matter how good it is.” Such job evaluation systems are products of machine age thinking. They assume that organizations are machines consisting of structurally defined tasks whose outputs are determined by their structures. All inputs are, therefore, limited to job statements. The relevant human elements, be it the personal judgment of the manager or the characteristics of the occupants, are conveniently eliminated from the process in the name of objectivity. There is an overriding concern with the ease of accuracy and measurement. In the name of objectivity, the process gets linked to the easily measurable dimensions such as years of experience, levels of formal education, number of employees, size of budgets, and so forth. This reconfirms the fact, widely ignored in human systems, that “the wrong criteria accurately measured” produces unintended and self-defeating consequences. The following list summarizes some of the conventional system consequences, which are widespread in organizations driven by such a model:

• Encourages empire building (inflates budget and staff to achieve salary-earning status)

• Encourages bureaucratization and resistance to change

• Rewards mediocrity and discourages differentiation based on talent and performance

• Encourages promotions to higher levels of incompetence as a means of salary increase

• Creates inflated (top- and bottom-heavy) organizations

• Generates indifference and alienation

• Raises the entire pay base by averaging the whole system rather than selectively differentiating the occupants in terms of their performance

• Replaces the need for achievement by the need for power

8.3.6. Mediocrity, Tolerance of Incompetence

XYZ operates in a force field that drives everything toward average. The gravitation toward normalcy comes from three separate and yet interrelated areas:

• A cost plus regulatory environment, and irrelevancy of performance criteria

• Commitment to a non-competitive culture

• An input-based personnel policy

The convergence point of these reinforcing drivers generates an entropic process, a systemic gravitation to non-differentiation and uniformity. The welfare of the system, therefore, requires maintenance of a state of predictability, harmony, and conformity. Risk and tension are anathema. Motivation to achieve competitive advantage and desire to excel are invitations to disruption and a serious threat to peace and healthy balance. Differential tendencies away from the established norms are discouraged. Innovation and entrepreneurial tendencies are treated as social pathologies, discordant deviations from the state of normalcy. To maintain this desirable state of uniformity and equality, the system has to develop a capacity to tolerate incompetence. Success is defined by being average, maintaining a low profile, and making no noise. Consequently, the system, under inertia, slips into a downward spiral of organizational ineffectiveness. Vitality suffers; banality sets in. When competence becomes irrelevant, then nobody is indispensable. Therefore, maintaining a proper relationship with the source of power becomes the ultimate criteria for success. If left unchecked, this process will ultimately result in an unacceptable level of non-performance. To counter this and produce the necessary levels of output, the system has some degrees of differentiation. Unfortunately the only feasible means for differentiation, under the circumstances, is the creation of multilayer hierarchies. Proliferation and subdivision of real tasks into insignificant jobs allows successive cycles of promotions to the levels of incompetence. The by-products of an overpopulated workforce further obstruct the workflow. Since the strength of a bureaucratic chain is determined by its weakest element, the organization became increasingly self-absorbed. Inflated workforce took a life of its own and created enough internal work to keep it busy. Redundancy proliferates. Process becomes an end in itself. Need for duplication is never ending, since those who want to do something realize that they could hardly rely on others for effective and timely support. This context is responsible for the experience of the following paradoxical duality. An implicit appreciation and desire to preserve the system that produces these opportune levels of generous benefits, security, and peace of mind militates against the natural human desire for a rational alternative that promotes earned distinction, legitimate authority, and recognition through superior performance. Witnessing the wasteland, therefore, pains the social conscience. Widespread expressions of frustration and criticism are reflections of experiencing this ongoing tension. The frustrating struggle of trying to resolve this dilemma gives rise to the prevalence of a denial syndrome: a tendency to blame the actors for the shortcomings of the system rather than the system itself.

8.3.7. Structural Incompatibility

XYZ is faced with a series of incompatibilities in its architecture (structure, function, and process) that arise from the requirements of new realities in its environment. The present structure of XYZ is consistent with an organizational legacy that proved extremely successful in an era when the system was operating in a stable and growing environment. It is a typical organizational structure, a dominant form of organization in corporate America today. The model was initially developed (by Alfred Sloan of GM) to meet the increasing challenges of managing growth in diversified markets. The basic architecture of this model is made of a series of semi-autonomous divisions operating under the central control of a powerful headquarters (the brain of the firm). Each division is a miniature of the whole and responsible for operating in a predefined product/market niche. The assigned niche defines the identity, viability, and scope of the operation of each division. The required competency of each division is a prediction of the demand and preparation for it. Otherwise, the divisions are expected to follow a pre-established mode of operation with no deviation. The administrative functions are the essential means of central control. These functions are duplicated throughout the organization. Conversely technical competencies are diffused and differentiated across product divisions in the form of local technologies. Since each division is to operate with a predefined product, technology, and a given market territory, interactions between them are minimized. This reduces conflict and complexity and increases focus and accountability. Success is achieved by staying the same and cloning the product divisions in several markets, a perfect model for a stable and growing and predictable business environment. This perfect structure, however, becomes grossly dysfunctional in an unstable and unpredictable environment latent with new sets of obstructions and opportunities. To be viable in this environment requires flexibility and core competency. Note that state-of-the-art capabilities, which are specific to a particular operation and cannot be successfully duplicated in different contexts, are not considered to be core competencies. Incompatibility of control and service functions at the corporate level produces unnecessary confusion, making both functions ineffective. Service providers are expected to perform a control function while simultaneously providing a service. As a means to avoid the control/service conflict, services that could be easily and effectively shared are duplicated. This chimerical quality results in continuous boundary disputes and loss of accountability. On the other hand, control functions, by being part of a service company, lose their proper legitimacy to be taken seriously. This, especially in a context of a culture that avoids bad news and conflicts in exchange for peace, does not provide a proper setting for an effective learning and early warning system. It reduces the control function to a minimum, mostly a bureaucratic form (i.e., supervision). Finally, determination of the attributes and capabilities that are to be common to all parts of the organization and those that are unique to specific parts of an operation is of paramount importance. The critical question, then, is the process (how) by which these objectives are to be achieved. Ironically both centralization and decentralization, as two complimentary processes, can be instrumental in this regard. So the question is not whether to have a centralized or decentralized operation, but to distinguish between what should or should not be centralized/decentralized. This question cannot be resolved free of context; for example, as long as a business is operating under a regulated environment, it makes a lot of sense to centralize the administrative functions. This will easily produce the internal consistency and uniformity that are so essential to regulatory oversight. But if it becomes necessary to operate in a non-regulatory environment as well, then centralized administrative functions, in their present form, will surely stifle the new businesses. They should be decentralized to keep them confined to the regulated business.

8.3.8. Uncertainty About the Future

XYZ, like other members of the energy industry, is entering uncharted waters. Once characterized by the stability of a publicly regulated environment, the industry has suddenly found itself in the throes of unpredictable change. The familiar and closely knit environment is being thrown open. Deregulation is ushering in the market and competitive forces will reshape the industry beyond recognition. The future, if anything, is uncertain. No one knows, with any degree of certainty, what it will look like. What is certain, however, is that the future of the utility industry is not going to be what it used to be. The only certainty will be uncertainty. The challenge is to excel in an environment where the competition defines the opportunities and the end user picks the winners. Great Britain and Canada are already in the throes of total utility restructuring. Washington and Wisconsin are leading the United States and began experimenting with new forms and relationships for doing the same differently. Connecticut has taken a “wait and see” approach and others, such as Massachusetts, are bracing for the turbulence that lies ahead.

No one knows what direction the future of the utility industry may take, but there are speculations, which include:

• Opening the energy industry to market-driven competition and management

• Emergence of the independent producer as a major player

• Rise of brokerage: wholesale traders and, in particular, retail wheelers

• Prospects of a change in cost equation by inclusion of the environmental costs

• Rate differentiation

• Introduction of mergers and acquisitions

• The prospect of limited growth opportunity in the traditional energy business

The emerging new reality, whatever shape it takes, will be pregnant with an array of new threats and opportunities. In light of the possible impact of the emerging reality, different stakeholders have already begun reassessing their expectations. Most important, the prospect of limited growth of energy is the source of anxiety not only for the stockholders but all the other stakeholders of the organization, because the viability of the system is growth based. Insufficient growth will have two disturbing effects: internally, it will upset the built-in cost increase system, and externally, the emerging new game will disrupt the peaceful coexistence of the peer utility companies. The game will become essentially zero-sum; some will win at the expense of others. Anxiety seems to be the order of the day.

8.4. The present mess

8.4.1. Drivers Defining the Behavior of the Present State of the Economy

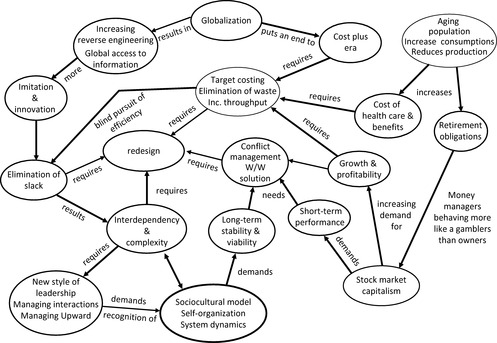

Discussion of the formulation of the mess would not be complete without at least partially dealing with the critical drivers that define the behavior of today's economy. The following interactive models represent an attempt to capture the interdependencies among the major drivers and demonstrate the nature of the complexities characterizing the emerging current mess.

8.4.2. How the Game Is Evolving

The first formulation (Figure 8.6) captures the dynamic interactions among four critical issues:

• Globalization

• Stock market capitalism

• Aging population

• Realities of sociocultural systems

The model demonstrates why design thinking is rapidly becoming the basis for executive education. The scheme not only deals with the impact and consequence of each of the four drivers, but it also captures their reinforcing effects.

Globalization has two critical impacts. First, it puts an end to Alfred Sloane's famous and dominant cost plus model. Price is no longer considered a control variable; it is defined by the global market. Cost is increasingly becoming the control variable. To compete cost needs to be reduced and throughput needs to be increased. But cost and throughputs are design driven. To reduce cost by an order of magnitude, the product and the throughput process need to be redesigned. The second impact of globalization is increasing global access to information and knowledge and thus reverse engineering. This leads to imitation as well as proliferation of technology. To cope with this duel challenge also requires redesign.

Iteration of redesign and need for continuous improvement increasingly removes slack and redundancies from the system and makes the interdependencies among the parts more and more pronounced. This is the essence of emerging complexity, which demands a whole new form of leadership — managing interaction and managing those you do not control. Managing upwards requires a paradigm shift and understanding of the sociocultural model, self-organization, and nonlinear dynamics. This ironically leads back to learning design thinking.

The aging population also has two impacts. It increases the cost of health care and retirement obligations, which puts additional pressure on cost reduction. In addition, retirees have a tendency to rely heavily on money managers to manage their savings and provide them with income for a much longer life expectancy. Money managers usually do not act as long-term, interested stockholders; they are more like gamblers who will cash out at an opportune time to bet on a more promising horse.

Expectation of stock market capitalism for double-digit growth and short-term earning performance that is met by emphasis on quarterly performance and continuous mergers and acquisitions conflicts with the stakeholder's expectation of long-term viability and stability. To dissolve this conflict and create a win/win environment that presents both short- and long-term success requires redesign capability.

8.5. Current crisis and future challenges

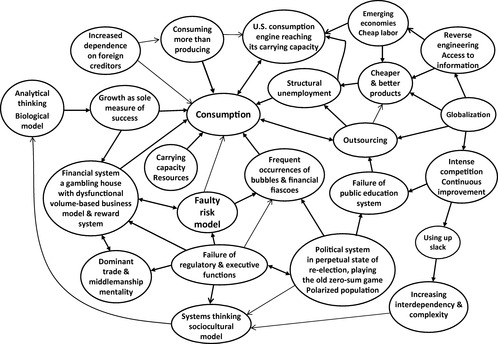

In the second model (Figure 8.7) I have tried to capture interdependencies among other drivers and obstructions that have a major impact on the emerging mess and the future challenges. These concerns include:

• Growth as the sole measure of success

• Behavior of financial systems

• Failure of public education

• Outsourcing and realities of globalization

• Structural unemployment

• Radically polarized population

• Political system in a perpetual state of re-election

• Carrying capacity of American consumers

To sustain a growth paradigm, based on biological thinking, requires increasing levels of consumption. Unfortunately sustaining double-digit growth, which has become the unquestionable expectation of “stock market capitalism,” is not feasible and the dominant growth paradigm, despite its tremendous success, is reaching its carrying capacity. The problem is reinforced by the behavior of a financial sector with a volume-based business model. The banking sector, instead of performing its critical function of providing necessary loans for operation of the economy, is engaged in trade and middleman-ship, enjoying 57% of corporate profit and draining the talent pool with a disproportional reward system, while the economy is in recession with more than a 10% rate of unemployment. Failure of public education (25% dropout rate), combined with the realities of globalization, and outsourcing have produced the unfortunate persistent levels of structural unemployment. But above all, the political system, with a radically polarized population, is engaged in a perpetual state of re-election and playing the zero-sum win/lose game. It is in no position to deal with the emerging level of complexity and challenge confronting it.

Unfortunately, dissolving this complex mess is beyond the capability of any disjointed efforts. Maybe the time has come to question the validity our growth paradigm and analytical thinking. A shift in paradigm may be in order.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.