1

The Problem and the Promise

The war for talent is over.

Talent won.

If you're the leader of an organization or a team, it's a pretty safe bet that time is precious to you. You want people to get to the point quickly. We'll do that for you right now. Here's this book in a nutshell:

- People know that hiring is important.

- They know that their “system” of hiring is broken.

- They don't know how to fix it.

This book is not for HR professionals, though they may benefit greatly from it. Instead, this is a book for you the leader of a team of any size. It will give you specific, actionable advice about how you can not only fix your hiring problems, but how you can turn hiring into an astonishing competitive advantage. You will improve your hiring quickly, substantially, and measurably. If you wish, you can do all of this without buying any software. The transformation will not be easy, but we will lay out for you a proven method to make it work.

There you have it. That's the book.

If you've reached a point where you have had enough with the pain and chaos of hiring and you want to get really good at it, then you've come to the right place.

The Sorry State of Hiring

We'll get much more detailed later, but let's take a quick, depressing tour of what hiring looks like in a great many organizations. We'll look at hiring from several different perspectives.

Candidates

You may have spent a lot of time thinking about your brand. You may even have detailed, expensive campaigns that focus on what you want to be known for in the mind of your target audience.

Then there's Glassdoor.

It has 50 million unique monthly visitors. It only takes a few clicks to see what employees right now are saying about your brand, and what candidates are saying about the interviewing and hiring process.

Within minutes of walking out of an interview, candidates will post reviews with explicit descriptions of how they were treated. Occasionally, those observations are good; much more often they sound like this:

- “I sat in an empty room for a half hour. I think they forgot about me.”

- “The interviewer walked in and said, “Now, you're here for which job?”

- “I'm a woman and was being interviewed for a technical position. The interviewer sat down and goes, ‘Maybe you'd be interested instead in the position we have in our design department?’”

- “I have a name that's not common in America. Throughout the interview they butchered my name and couldn't even settle on one incorrect pronunciation even after I corrected them.”

Anyone can view Glassdoor ratings. But we at Greenhouse benefit from an additional, eye-opening vantage point by virtue of having more than 4,000 organizations as customers. We also live and breathe hiring, so we hear a lot about hiring practices at organizations of all sizes and stripes. Here are typical situations.

Interviewers

We regularly hear words to the effect of “Shortly before I'm supposed to interview someone, the recruiter will hand me a résumé and say, ‘Spend an hour with this person. Tell me if she's any good.’”

Interviewers are often given no training or instruction on how to conduct a good interview. In addition, they may have no idea what other interviewers will ask or who they even are. As a result, candidates will have three people in a row say to them, “So, tell me about your last job.” Untrained, clueless interviewers will also ask irrelevant or even downright illegal questions, like “Are you planning on getting pregnant?”

When there is no interviewing plan, it's common for interviewers to ask one-size-fits-all questions. They may spend time during the interview brainstorming what their next question will be when the candidate stops talking instead of focusing on what the candidate is saying at the moment.

And because there is no coordination between interviewers in terms of who asks what, gaps can occur where no one asked about important aspects of the job.

If there is no discipline around writing down one's impression right after interviewing a candidate, then soon all those sessions blur together:

“I thought Chantelle was good.”

“Was she the one in the green sweater?”

“No, you're thinking of what's-her-name.…”

Recruiters

Recruiters are extremely busy people, even in the best-run operations. They do heroic work, often with little or no credit. In most organizations, they struggle to keep up and are always putting out fires.

If the day of the week ends in a “y”, then the pressure will be on to deliver candidates. Recruiters are often given extremely little information about the positions they're supposed to fill right away. At these organizations, recruiting is the recruiter's job—a largely administrative one with no recognition. For everyone else, it's a burden that takes away from their “real job.”

A recruiter may identify ten candidates and send them to the hiring manager with a note: “Here's the latest. Tell me what you think. Are these the kind of candidates you're looking for?” They'll get back an email with this helpful, descriptive reply:

“No.”

Recruiters may go to great lengths to piece together interviews for a sought-after candidate to fill a key role, only to have an interviewer show up late or not at all.

Sometimes the pressure on recruiters will result in their not taking the time to use the Applicant Tracking System (ATS) or other tools in the department: “Hey, do you want me to fill these openings, or do you want me to fill out forms?” Soon, this means the tools do not reflect reality and therefore, aren't useful, so why bother to update them? A classic downward spiral.

Hiring Managers

Hiring managers routinely feel as if they're in the dark and are frustrated. They're the ones who requested that a role be filled. They are on the line to fill that role in order to make their numbers, yet they have little meaningful data, no transparency as to what's going on, and no predictability. They often feel as if they're at the mercy of the recruiter and are forever asking, “Where are we? What's going on with this job?”

Just as recruiters under pressure will ignore the systems and tools, hiring managers under pressure will take matters into their own hands. A few years ago, we asked the head of equity derivatives trading at a very major firm how he hired. He said:

How do I make a hire? Here's how it works. I need to hire a trader in Manhattan. I tell someone in HR, and someone in Cincinnati emails me a Word document with a job description. It's absolutely meaningless B.S. It has nothing to do with my business. It's a bunch of jargon. So I look at it, okay, whatever. And then they go away for three months and tell me that they're recruiting for this role. And I hear nothing, I know nothing. Many weeks later, they still haven't made the hire or even sent along any candidates. So, I go take my buddy out for a beer. He's an equity derivatives trader at my old firm. He hooks me up with a couple of people he knows who are solid traders and I meet with them. I really like one. I then email HR and say, ‘I got this person; here's their résumé. They're perfect for the job, so hire them.’ HR puts the person in the system and they get hired.”

It turned out that the formal hiring process at the firm added zero value and the managers were left on their own to figure out how to hire. The hiring of the new trader was not based on a rigorous, structured process that would have helped to minimize bias and deliver the best candidate.

Because hiring managers feel such pain around the process, they may hold onto underperforming employees much longer than they otherwise would: “Maybe I'll suffer with this person and make do; after all, who knows how long it will take to get that role filled again?”

The C-Suite

A venture capital (VC) firm put on a conference for CFOs and invited us to speak about the ROI of good hiring practices. These were some tough, numbers-driven folks. At the end of the presentation, one guy said, “Okay, okay, I accept your premise. I accept your framework for how to think about hiring and I think you're right. That is how we should think about it. But this is HR! If I give them that money, I won't get any of the results you're talking about.”

That type of comment is indicative of a breakdown in communications between the recruiting and business sides of the organization. That leads to the downward spiral of lack of trust and lack of funding. The C-suite can be a place where maximum pressure to deliver results meets maximum distance from detailed information about the status of hiring:

- “We're trying to grow and it's not working.”

- “We've spent a ton of money on systems and I can't get any decent reports.”

- “We know that we have an issue with meeting our diversity, equity, and inclusion targets, yet all I hear are generalities about ‘It's a top-of-funnel problem; there just aren't enough engineering applicants who are women.’”

- “We have as a goal to increase the number of people we promote from within, and we post all the positions. Why is it that we always have to look outside to get the key roles filled?”

Employees Who Refer Friends

Even poorly run organizations recognize the cost savings when employees successfully refer friends for jobs. As we'll talk about in Chapter 6 about finding the best talent, internal referrals are indeed a great thing.

When employees refer their friends, their personal brand or reputation is now at stake. If the hiring experience goes well, then friends stay friends. But too often it's a case where the employee hears about her friend's terrible experience—or never hears anything—and is embarrassed for herself and for the organization: “Oh my gosh, I'm so sorry. It's actually a good company, but that was an awful experience they put you through.” That has a way of quickly drying up the referral channel.

What Hiring Looks Like at the Best Companies

You should know right up front that when we refer to “the best companies,” we do not mean the companies that have the largest list of amenities like gourmet chefs, dog walkers, and dry-cleaning services. Those may be nice, but in some cases they can be poor investments, as we'll see in Chapter 3 when we discuss the ROI of hiring.

Instead, we're referring to the companies for whom hiring has become a huge competitive advantage. It's become woven into their culture so that people support each other to do the right things, and pressure each other when someone reverts to the old ways.

Speaking of the old ways, it's common for people to spend decades being employed in multiple organizations and for them never to see hiring done right. It's always been a mess wherever they worked, so they just kind of assume that “it is what it is” everywhere. Here is what great hiring looks like.

Candidates

When people come across your job posting, the first thing they'll notice is that it's not this dry-as-dust, bureaucratic-sounding document with specifications. It sounds more like an enticing advertisement than a job posting.

If they get an interview, they'll get a detailed document giving them all that information they would otherwise sweat about: where to park, what door to enter, what to wear, and what will happen.

The candidate will have recorded his or her name in advance, so everyone that day will know exactly how to pronounce it.

The interview experience will be friendly and crisp, with each interviewer meshing with the other interviewers, so relevant questions get asked once and all the bases get covered.

At the end of the interview, the candidate will know exactly what the next steps are, and when they'll happen.

When candidates are treated this way, it's not uncommon for them to leave positive Glassdoor reviews even when they did not get the job.

Perhaps most important of all is what happens when you're after the most-sought-after people to join your organization: You can bet that they're weighing multiple job offers and checking out Glassdoor. You can also bet that most of those other hiring experiences will suck.

Interviewers

As soon as you get scheduled for an interview, there's a link in the invite that says you're going to go interview Robbie MacGregor. You click on it and are taken to page with everything you need to conduct a great interview:

- The tasks that are expected of you

- The list of questions you will ask

- A link to any material we have on Robbie, like his résumé and supporting documents he sent in

- The scorecard that you must fill out right after the interview. It's got all the criteria that have been agreed upon as important for this particular job. It is by no means a one-size-fits-all scorecard.

When you meet with Robbie, you are relaxed and attentive because you're following a clear and effective system. After you meet with him, you make a point to fill out that scorecard promptly and completely because you don't want a repeat of that one day when you were called out by the rest of the team for wasting their time.

Recruiters

In the best companies, recruiters are still extraordinarily busy people. But it's a good busy, because they're treated as partners by the hiring managers. They know each other's roles, and there's a mutual respect between them.

Before any applicants are screened or interviewed, the recruiters will be brought up to speed about what this job involves, how it's different from last year's positions, what the key requirements are, and what phrases or lingo to use so that candidates know they're speaking with a person who actually knows something about the position.

Recruiters live in the department's tools, meaning that they use those tools and systems rather than create their own spreadsheets on the side. Better discipline around tools and systems results in more reliable data.

Hiring Managers

Hiring managers still have the stressful challenge of meeting deadlines and goals, but the big difference is they're not doing so in the dark. Systems are not only continually updated, but they work in concert with each other, and that brings a level of regular awareness about the current hiring trajectory in relation to goals.

When the time comes to make decisions about filling positions, those decisions are made with data and confidence, and not merely by the preference of the loudest person in the room. Also, because the hiring manager and recruiter worked closely from the outset on what were the key characteristics needed to fill the position, decisions happen faster and without the false starts that poor communication causes. Those decisions can also stand scrutiny because the process reduces bias.

C-Suite

The really big difference here is you have a level of confidence that you'll be able to hire the staff you need in order to make your numbers.

You have a detailed understanding of the talent plan, how the organization is doing against that plan, and clear expectations for what is going to happen next.

Part of the reason why you have all this good information is you've made a major effort to get visible about how hiring is crucial to the organization. No staff meeting happens without a discussion of hiring. The organization celebrates meeting its sales goals, but it also celebrates meeting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) goals and other hiring benchmarks. You expect all managers to be equally involved with hiring efforts and achievements.

Employees Who Refer Friends

It feels great to be able to actually help friends when they need it, and helping them with a positive job-hunting experience is a big deal.

Of course, the best outcome is when you refer a friend to an organization and the friend is hired. That's especially true when it's a good fit based on data and a thorough interviewing process. But even when your friend doesn't get the job, if it was a positive interview experience then everyone benefits to some degree.

Employees at organizations with great hiring practices become a legion of ambassadors, spreading the word to similar people, literally day and night after work.

“Yeah, right. In your dreams.”

In this book, we're going to stop now and then to address a thought that we're pretty sure you may have at that moment. Right now we suspect that you're torn between being excited at the prospect of becoming badass at hiring—but you feel like your organization will rise to the occasion like a boat anchor. “Our organization is different,” you say. “That might have worked before, but not in today's tough competitive environment,” you say.

We are here to tell you that normal organizations have made this transformation in good times and bad. It's not, as they say, rocket science, nor is it fantasy land. It's actually pretty straightforward stuff.

If we're going to be blunt with each other, you better hope that you're reading this book before one or more of your main competitors does. If they actually read and adopt just a portion of these practices, they're going to kick your butt.

There's a catch, though.

Isn't there always a catch to things that sound too good to be true? So, here's the tough news about this opportunity:

To create hiring excellence in your organization, you as the leader will need to change.

As we said at the outset, this is a book for leaders of organizations, and leaders are extremely busy people. Be that as it may, you're going to have to get much more personally involved in hiring in order to pull this off.

Yes, you have a whole HR department whose job includes hiring. That should be enough, right?

Wrong. You have to become what we call a Talent Maker, which we will describe in much detail in Chapter 9. Your HR department needs you to step up and not just say but show that hiring is a priority. You need to create the space for people on your team to work on the business, as well as in the business, in order to effect this remarkable transformation.

In the years since we started our company, we've been on the lookout for magic bullets to make the change happen instantly and painlessly. Alas, so far we've only been able to find the next best thing: a proven method for putting in the time and hard work in order to create an additional major asset, namely your ability to hire great people at will. This book will show you how to do it.

“So, the Greenhouse founders wrote a book about hiring. It's going to be one long sales pitch for their products.”

We are extremely well-known in the recruiting world, and therefore, it's understandable to have HR folks associate us with being an ATS provider. In case you've never heard of an ATS, it's a common tool in organizations, and it does what it says: tracks the status of applicants, candidates, interviews, job offers, and so on.

Let's get something out of the way: We think we offer a great product, and it's much more than a mere tracking system. You can read all about it on our website. It can accelerate the transformation of your organization. We hope you try it. There, that's our sales pitch.

Back to this book: It is not about our software; it's about the principles of world-class hiring. You do not need our software to become amazingly good at hiring. You can use a free word processor and spreadsheets if you wish. That might not be the most convenient way, but it will work.

Let's put it another way: If you continue with your hiring mess and change nothing, and if your competitor implements just a fraction of what we'll discuss here but uses Google Sheets and Microsoft Word docs, you're in for some rough sledding. Instead, be that competitor who implements. If you want to activate a major hidden tool for organizational success, you don't need any software but you absolutely must become the Talent Maker and catalyst for your team.

Therefore, you'll hear us refer to Greenhouse a lot in this book. When we do, we mean our method and culture of hiring, not our software.

So, why isn't a great ATS the solution to great hiring? Because it's not about tracking poor behaviors better; it's about changing behavior. It's about solving a different set of problems, which relate to how priorities are set, what actions get taken, and how decisions are made.

We actually had a competitor who at one point launched a whole advertising campaign. In effect they said, “Take the hassle out of hiring. We're going to make hiring so easy, you can finally get back to the real job of building your company.”

That was both extremely funny and kind of sad at the same time. All organizations are built from three components: people, capital, and assets. The assets may take the form of intellectual property, machinery, raw materials, signed contracts, whatever. Of those three components, only one—the people one—can create the other two.

Hiring is the mother of all variables, the one that can boost performance to the moon or can crash a company in no time flat. And organizations hope to buy some ATS so they can get back to their real work? That's the attitude of the walking dead, and they don't even know it.

Unique Window

As we said, we have a window into the inner workings of organizations of all types, from the titans you hear about every day, to hyper growth start-ups, nonprofits, multinationals, and old-line established firms. Of course, we're very careful to protect confidentiality and obscure details when necessary. But in these pages you'll get insights that are almost impossible to get any other way: They represent many more experiences than any one person could have in a lifetime. They're more than a management consultant would have because they're rooted in the deep inner workings of thousands of organizations over many years.

Even so, please note that we do not have all the answers, and don't pretend to. We're merely on a journey to get better at hiring and to spread that culture to like-minded organizations with a willingness to listen, try things, occasionally stumble, and always pick themselves up. Including hiring in your core focus is unbelievably rewarding.

“But do we really need another book about hiring?”

Lots of books—including some good ones—talk about how to recruit: ten subject lines to lay on candidates to make them open your email, how to pitch a job, how to do a good interview, how to convince a candidate to take a job, and the like. It's at the practitioner level.

This is not such a book. As we said earlier, we want to have a discussion with leaders, whether they are the C-suite, a department head, middle manager, or team leader. We think a breakdown occurs in the interface between people who are tasked with recruiting, and those who are tasked with the business side and think they can delegate hiring to HR. We want to offer a proven framework for creating an internal alignment and commitment that works for everyone, and succeeds in attracting amazing talent.

If we do our job in this book, the head of HR and the CEO will give a copy to each other.

Companies need people more than ever. At the same time, people need companies less than ever.

Daniel: I graduated from a top engineering school in 1995. When I thought about my options for becoming a programmer, there was only one—work for a company. That's because there was no infrastructure for me to do my own programming work. Software tools cost $1,000–$2,000, and they ran on computers costing around $4,000. They had to be connected to a network running at a company, and remote work was not possible.

When I applied for jobs, I first went to the bookstore in downtown Ann Arbor and I bought a directory that listed the names of companies, their head of HR, and their mailing address. The problem was that the books were published by city. You thought about what city you might want to work in, and you bought a few of these books. There were no online job listings or much of anything online at the time. I had no idea what their salaries were, what the culture was like at the company, or even if there were any job openings to begin with. There were no postings in these books because of the lead time from when the companies submitted their materials and when the printer published and distributed the books.

Sure, I attended job fairs at my school, but only a handful of companies made it to those fairs, and even for those companies, information was scarce. In a real sense, the amount of information I had on a company was not much different from what one of Charles Dickens's characters had on a company in London in the 1800s.

Still, I felt pretty high-tech at the time because I didn't have to type out my résumé and application but could use a word processor! I printed the paper, stuck it in envelopes, and mailed it to companies. Outside of small networks where maybe a friend knew a friend who worked somewhere, I was completely at the mercy of what the company wanted me to know about it.

Let's compare that experience to someone graduating from school just 25 years later. I can easily strike out on my own with programming. I can log into GitHub for free and produce my own software. In fact, I have access to the most powerful design and programming tools in history and they cost me nothing.

I can instantly and immediately distribute my software anywhere in the world. It's my choice whether I charge for it, or give it out for free as a loss leader for the personal brand I might decide to build.

If I feel like exploring the jobs available to me in organizations, I have a global database of basically every white-collar professional at the click of a button. I can get the real-time lowdown from Glassdoor about what it's like to interview or work at any company, and it's uncensored.

I can explore different job openings by filtering as widely or narrowly as I wish. I can also check out job types that I would never have thought about pursuing, were it not for the ease of doing research now.

My word-of-mouth network is vastly larger, because it's so easy to see who are friends of friends and get introduced to them. I can instantly apply to crazy numbers of jobs, and in many cases work from the other side of the globe.

In short, I have astonishing amounts of information and transparency about the job market. In addition, tools make it possible for me to have side hustles or be self-employed full time if I wish from anywhere. The relatively recent days when companies controlled information and you had a choice of a handful of companies (or TV stations) is long, long gone.

People still do apply to jobs, but increasingly it's the jobs that are applying for people. Let's say someone is an engineer, logistics expert, or environmental attorney and starts a new user group on LinkedIn or somewhere else. For a little, while there will be only like-minded people in the group. Pretty soon a recruiter will sniff around, hear about the group, and get added. Secrets don't have a long half-life in recruiting, so before long a bunch of recruiters are in the group, spamming subject-matter experts with offers to interview.

It's true that jobs will often have dozens or even hundreds of applicants. But employers would be making a big mistake if they think that means they have all the power. First, the most competitive candidates have multiple job offers, as we mentioned earlier. Second, a lot of applications are submitted by robot, where someone can click a button and blast a résumé far and wide. Therefore, the number of qualified, desirable, available candidates is far smaller.

What we are seeing in organizations is there's a shift happening, where the head of sales and the head of engineering are increasingly realizing that the success of their own position is based on how well they hire and retain real talent.

Boards are also sitting up and saying things like “What exactly is your hiring plan for the next quarter and next year? Because if we extrapolate the lines on these graphs, you're not going to make your numbers without those positions being filled.”

This system stems from the experience of a great many organizations.

Our approach to hiring is the result of the founders' experience and also the refinements and suggestions from our community. At the start of this book, we think it may be useful for you to understand the beginning of Greenhouse, and how it came about as a result of real-world hiring challenges.

Daniel: I started a consulting company in the early 2000s. Our firm would hire programmers and put them on projects at banks. Early on we didn't have any brand or market power to speak of. What I did have was an engineering and programming background and I was extremely strict about the level of quality that we would accept for a programmer.

Soon, we got a call from a big-name firm in Manhattan, and we had just the person for their needs. The bank would not take our word for it that our person could do the job, and they insisted on interviewing him. I proudly sent our programmer to Midtown, knowing that he would blow the doors off the interview.

After a bit I contacted the client and was told, “Oh, yeah, we rejected that person.” I'm thinking: What? This guy was unbelievably good! Cream of the crop! It made no sense at all. I asked the programmer what happened. He said, “I sat in a whiteboard room with some guy who was totally bored. He obviously had zero interest in being in the room, and barely looked me in the eye. He asked me the nit-pickiest little questions about some obscure, unimportant programming syntax that no one ever heard of or uses. Then the meeting kind of ended and he walked out.”

Wow, that was weird. Hey, maybe it was bad chemistry, or maybe my guy said something that caused a problem, because it certainly was not his level of skill that could be the issue.

But it happened again—and again. And with different programmers and banks. I soon realized that at these big banks, they were just asking one of their programmers to do the interview and putting them in a room with no guidance or instruction whatsoever. The interviewers weren't asking questions that indicated they knew anything detailed about the specific tasks we were asked to find someone for. No one was invested in this; in fact, it could be that the programmer/interviewers might have been a little worried that our people could end up being their replacements.

While this puzzle was unfolding, I was hiring and scaling my own team. Frequently, I had two of my people interview the candidates. I remember on one occasion when I asked how things went, one of my guys said, “That was the best candidate I've ever met. You should not let this person out of the building without making an offer on the spot.” I asked my other interviewer, who told me, “I'm not working with that woman! Do not hire her! Let me put it this way: If you put her on my team, I'm quitting!”

Am I in some kind of time warp? First, the banks make no sense with their response to fabulous candidates, and now my own team makes no sense! I knew both of my interviewers well and they were smart. I had to get to the bottom of this.

There was a Radio Shack in my building, so I went downstairs and bought two digital tape recorders. I gave them to my interviewers and asked them to tape all their interviews so I could listen to them on my commute to and from work.

I listened to a ton of interviews. It was probably a bad idea to be driving at the time because they melted my face. You cannot imagine how bad those interviews were. These were my own smart, hand-picked people, too! I had this epiphany: Oh my God, I'm sending my people into these rooms, and I haven't told them anything useful. Plus, I didn't give any instructions to the interviewers as a group, so I would hear four interviews of the same candidate by four different people. They all were asking the same questions.

Then the candidates would ask my staff questions. Some of my people would give terrible answers because they weren't trained or prepared. A candidate would ask, “So if I join this company, what will the projects be like?” And she'd hear, “Well, um, it kinda depends. Actually I was put on a pretty lousy project for all of last year. I know there's some good projects elsewhere in the company, but I'm not part of those.”

Hence my melted face. What are you doing? Are you trying to ruin my company? After about ten miles I realized that it wasn't his fault. I didn't prepare him for that or any other question. He's a programmer! He was shooting the breeze about his own job, not interviewing someone for a different job.

Okay, I'm an engineer. This is solvable. No one knows what to do here, but it can't be that hard if we all sit down ahead of time. We can agree on what's important for the position and come up with a scorecard. If we care about these five or six criteria, what questions or tests could we come up with that will tell us if a candidate is a star, or okay, or terrible for those criteria? It could be as strict as a programming test for a programmer or as loose as “sell me this pen” for a salesperson. Let's also agree on who is going to ask which questions, so we cover everything on the scorecard. Engineers use data. We're going to collect all these data points, look dispassionately at the data, and use it to determine whom we hire.

That simple set of procedures made all the difference in the very next interviews we did. Night and day. It's one of those things where you think: How could I have been such an idiot to not have thought of this before? And why are there so many other idiots doing the same thing, even in multi-billion-dollar organizations? I didn't have an explanation, other than the blind leading the blind: “This is how we've always done it. It's how everyone's always done it.”

Daniel and Jon met while in school. Jon's path had certain similarities:

Jon: I have a long history as a product manager. I worked at a company called BabyCenter back in 1997 when we were trying to figure out what the Internet was. After the company got bought, I became the first product manager at a company building performance management software for call centers, and then went to Johnson & Johnson, which had acquired BabyCenter and wanted to take it global.

The goal was to set up a media business with local pregnancy websites in 20 countries around the world. We'd launch a site, get a whole bunch of traffic, and then start selling ads against it. It was almost like a franchise model.

The big challenge was that we needed to find local editors in 20 countries around the world. Each editor in turn would need to hire a team—and all of this had to happen very quickly. So how were we supposed to find the best pregnancy editor in Rio, and Moscow, and Beijing, and Kuala Lumpur? We created a whole process around how we would advertise and network, then we planned how we would interview them, including testing their skills in their local language.

We were really under the gun and had to buy our plane tickets all around the world well in advance of even having any candidates identified in those cities. We developed a process so that when the time came to visit a city, we'd have four finalists to interview, we could make an offer on the spot, and get the training started. Then we'd move on to the next city. Our methodical process was good enough that 15 years later, I hear that some of the folks we hired are still there.

It's important to note that we built this effective recruiting machine even though we did not have an ATS.

Not long after, Daniel and I were both at crossroads in our careers. We'd had some interesting similarities in our experiences with hiring and we explored how we might capitalize on that in the form of a company.

We didn't start with the intention of creating an ATS; instead, we got out some index cards and mapped out the system we had in mind. It was everything we learned about designing a structured interview process.

We began to show our process to people we knew, one of whom was Fiona, a product manager at the New York Times. We showed her the steps, and the systematic approach to preparing interviewers, conducting the interviews, generating feedback, and making decisions based on data.

Fiona was like, “Wow, I never thought about it that way. This is easily the best plan I've ever seen for any hire and I'm actually going to use this.” We were just in research mode at the time, but that was pretty encouraging feedback.

Daniel knew the founders of a start-up incubator in Manhattan and he offered to do a class on how to do a better job of hiring. They put it in their newsletter and the next day the room was jammed with 30 people. The discussion went on for three hours.

Then we started to get emails. More than one said words to the effect of: “I was in your class yesterday. I went into work on Monday morning, had a meeting with my exec team, and we changed how we hire—that same day. Thank you!”

Well, that was about all we needed to hear in order to get us moving ahead in earnest. We did the necessary things like write a business plan, incorporate, and raise money. Before long we were up and running.

For quite a while we had no sales team. The buzz we generated from doing a few talks was enough to get the phone ringing. Pretty soon we were doing 10 demos a day and the fish were jumping into the boat. In short order we went from our first 25 customers to getting 25 a month and then 25 a week.

Throughout this book, you will hear about organizations that have adopted a structured approach to hiring. Some of the best improvements we've made to the process have come from suggestions by our customers. All of us, including Greenhouse, are on a path toward continually improving at hiring. The great news is that once you're out of the quicksand that is hiring chaos, you can regularly see the progress you're making.

How We Structured the Book

We like to think in systematic terms and so we've structured this book to give you a logical framework for great hiring.

Part 1: The “Why”

Chapters 1 to 3 relate to the importance of great hiring. You've already gotten a 30,000-foot overview of the background that led to developing our approach.

Chapter 2 takes you through the Hiring Maturity Curve, which is a detailed way for you to understand where your organization is on the continuum from nightmare to dream. You may think, Oh that's easy, we're a mess. But it may be that certain parts of your organization are functioning at higher levels than others. We'll see.

Chapter 3 is about the Employee Lifetime Value (ELTV) model. What gets the focus and priority in organizations tend to be the things where a return on investment (ROI) can be measured, like salespeople, new products, and so on. We provide a way to think about hiring in more quantifiable terms.

Part 2: The “What”

Here is where we dive into the specific competencies of world-class hiring.

Chapter 4 introduces the framework we call “Structured Hiring” at what you might call the 5,000-foot view. It's the core of our approach.

Chapter 5 lays out the first competency, which is to “Own every moment of your hiring experience.” This is primarily about the importance of breakthrough candidate experiences. We hope you will see the hiring process through a different, sharper lens.

Chapter 6 is Competency 2: “Identify and attract the best talent for your organization.” This is, of course, a perennial problem for most organizations, but here you'll discover a more predictable way to get the candidate flow you need.

Chapter 7 is about Competency 3: “Make confident, informed hiring decisions.” The only thing worse than not filling a position is filling it and then regretting it after a short, expensive time. That is much less likely to happen after you read this chapter.

Chapter 8 is Competency 4: “Use data to drive operational excellence and improve over time.” Having the right skills and behaviors to attract great talent is critical. When you intentionally design these things into automated, measurable processes, you will get to the realm of amazing.

Part 3: The “How”

Chapter 9 is called “Talent Makers” and it's all about your potential. Some leaders do things very differently from you with respect to hiring. They spend their time differently, talk about different things, and have different priorities. As a result, they get different outcomes. The good news is you can also do those things and get those outcomes. We describe the three elements that can transform you into a catalyst for attracting and retaining the people who will propel your organization to achieve amazing things.

Chapter 10 covers the challenge of “Changing Minds.” It's one thing for you to be convinced of the importance of becoming great at hiring. It's quite another to effect that change in an organization that's been doing things a certain way for a long time. We provide some approaches that have been effective in other organizations.

Final Thoughts wraps up the book with a couple of important recommendations for you, as you continue or begin your own transformation.

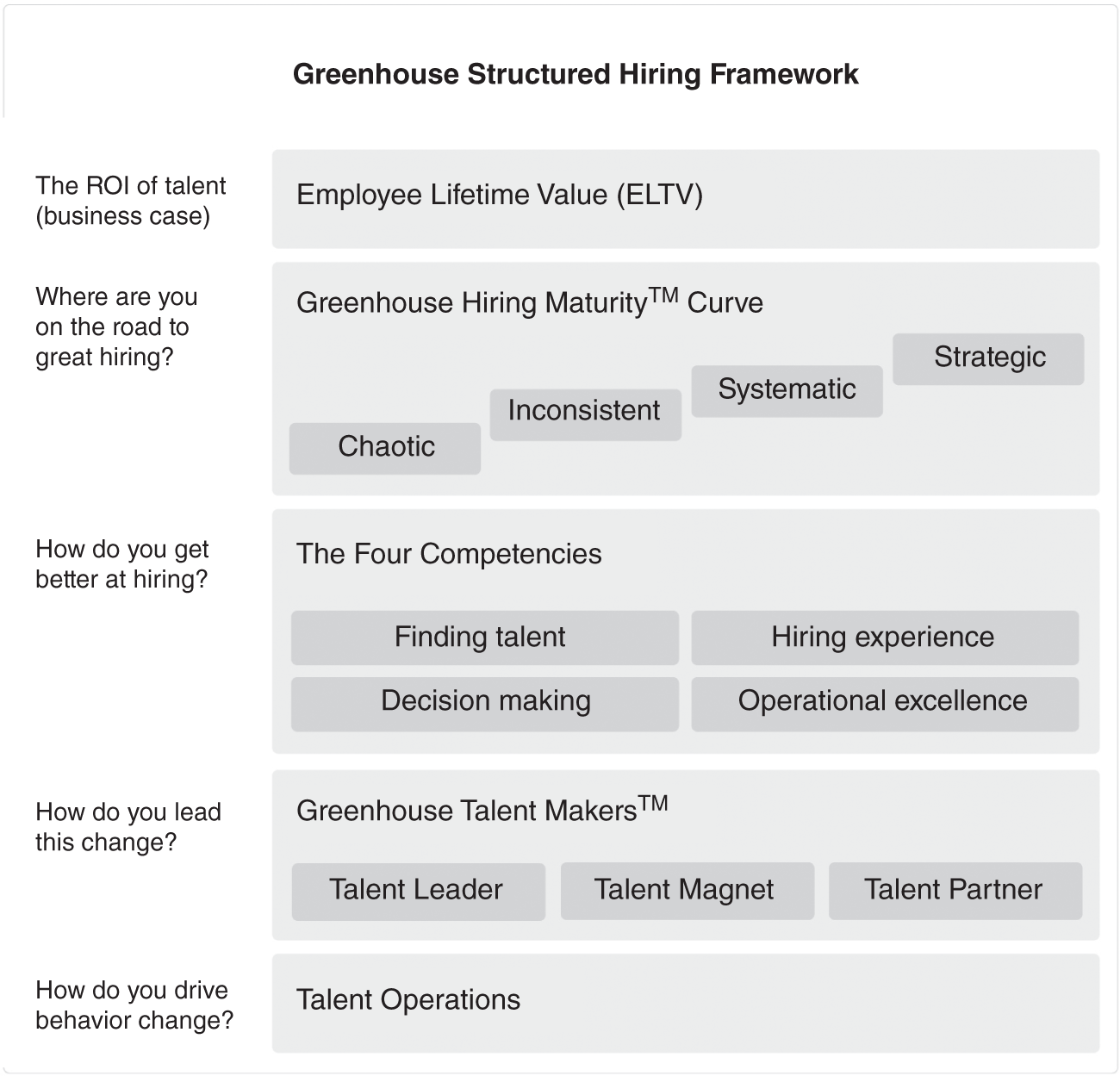

Structured Hiring Framework

We will be covering a lot of concepts in this book. As you read through the chapters, we thought it would be helpful to give you an overall framework for thinking about the major moving parts to structured hiring. You can see that framework in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The Structured Hiring Framework.

Of course, this single volume cannot contain all the examples and resources that we've assembled to support the many concepts you'll read about. Therefore we'll occasionally refer to a companion site we set up at talentmakersbook.com/resources. You'll not only find those supplemental assets there, but we'll add new materials as the hiring landscape changes.

Let's dive in, shall we?