Chapter 2

The Business of Talent Management

Josh Bersin, President and CEO,

Bersin & Associates

What’s in this chapter?

- The meaning of integrated talent management for today’s organizations

- The elements of the High-Impact Talent Management Model

- A business-driven approach to talent management

- The four steps in developing a talent management strategy

- The governance and business ownership of talent management

- How the key elements of talent management fit together

- The importance of organizational culture

In the last few years, the topic of integrated talent management has become one of the most talked-about issues in corporate human resources. As the head of a research analysis firm, I have the opportunity to talk with hundreds of companies about their definitions, implementations, and solutions for talent management. In this chapter, I share my firm’s findings about the real definitions, best practices, and applications of talent management in businesses today. In particular, this chapter discusses concepts of “business-driven talent management” with the goal of convincing you that, ultimately, talent management is a business strategy, not a human resources strategy.

Defining Talent Management

Books on talent management are certainly not new. In fact, the term “talent management” has been used for many years, referring primarily to management of “the talent,” meaning an organization’s top people. So “talent management” used to refer to the development and succession management of these top leaders. Today, however, the term refers to what we would call an integrated approach to managing all the aspects of an organization that have to do with people. Today the term refers to all the integrated practices we use to attract, manage, develop, and compensate people.

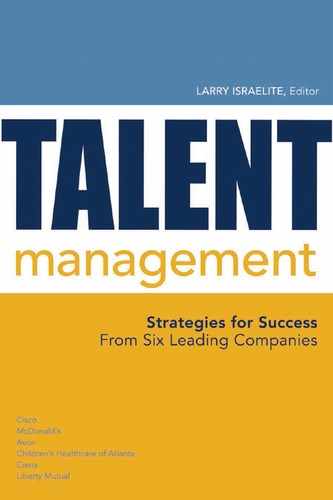

Before we get into the processes of talent management themselves, it is important to realize that in today’s organizations, “the talent” is everywhere. Organizations that used to be hierarchical no longer work this way. The traditional views of “talent” and levels of management that drive the organization have changed (figure 2-1).

In fact, in most highly effective organizations today, some of the most-valued employees (those in what one would call the “pivotal roles”) are functional specialists in sales, customer service, engineering, manufacturing, research, or support. These specialists range from young new-hire employees to senior people in their 50s and 60s. Talent management practices must accommodate the fact that people with high potential go beyond those who can be promoted to management; they are also people who can take on more responsibility as individual professional contributors.

At Qualcomm, for example, one of the world’s most profitable and successful technology companies, people with PhDs and patents are given some of the most important responsibilities. The company prides itself on “depth,” not “breadth,” in talent—because its core business is to out-innovate everyone in the mobile telecommunications market. If its leaders tried to manage Qualcomm with a purely hierarchical model, it would fail.

Figure 2-1. Redefining an Organization’s Talent Well Beyond Its Leaders

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Retail organizations have similar but different challenges. Their most important employees are the high-turnover workers in their stores. Management plays a critical role in recruiting, coaching, and managing these people, but research shows that some of the most important roles in retail are not only managers but the sales specialists themselves. (The source for this finding is proprietary research by Lowe’s Stores, which found that the “pivotal role” in its retail stores is the “sales lead,” a nonmanagerial role.) So how can a talent management strategy ensure that young, highturnover retail employees perform at the optimum level at all times ?

The Manager’s Changing Role

In addition to the flattening of organizations and the general agreement that “talent is everywhere,” we also have organizations that function as networks. Nearly every employee now has a cell phone and access to email, computer, and vast intranet resources. Many employees no longer even work in the same office or city as their managers; rather, they interact and work with teams across the world. Employees can no longer just walk into the manager’s office for help.

This means that many companies have a “matrix” management process, which means that employees both have managers who help them with personnel-related issues and also have a vast network of peers and project leaders with whom they work to get their work done. As a result, the belief that managing means providing one-to-one coaching and day-to-day support has changed. When we think about performance management, coaching, and development, we must consider how the process works across a network of people, not just in a hierarchy.

Consulting firms have been managed this way for years. Employees of Accenture, IBM, Deloitte, and many other accounting and consulting firms have many managers—they have “people managers,” and they have “project managers.” An employee’s ability to work within teams and interact with many people in a variety of roles and contexts is now a core competency. In fact, Bersin & Associates’ research shows that in these organizations, true performance is measured by a matrix of functional competencies (skil s) and span of influence (ability to influence, lead, and col aborate among large groups); for more information, see Lamoureux (2009). Thus, we must think of talent management as the process of managing this vast array of networked resources, not just providing tools to managers.

Talent Pools, Critical Talent, or Pivotal Talent

Finally, consider the fact that an executive cannot possibly manage everyone in the same way. Some roles drive more value than others. In software firms, experienced programmers can write 10 to 100 times as much code as junior developers. In oil companies, exploration and production engineers can drive billions of dollars of market value, while refinery employees have little or no real leverage on the bottom line. In insurance companies, key roles include actuaries and customer service leaders.

As companies implement talent management strategies, they quickly realize that they must focus their energies on particular groups of people, referred to as “talent pools” or “talent segmentation.” By implementing standardized talent management processes and systems, organizations can now target critical pools of talent that need attention and that can drive the greatest potential business impact.

One example of such a solution is the implementation of talent pools at one of the nation’s largest health care and insurance providers. In this industry, the nursing population is a particularly pivotal talent pool; nurses are in short supply, they drive tremendous enterprise value, and their role is changing from one of service delivery to consulting on wellness. Thus, this health care firm needs special types of managerial and talent programs to make sure that it meets its overall business goals.

In this firm, the chief learning officer worked with the CEO and labor leaders to develop a new leadership program focused on the se rviceprovider population. This program focused on providing all service-provider leaders (nurses, technicians, and other roles) with a broad range of skills. The company is using this program as a backbone infrastructure to help this critical population improve its leadership skills and transform its role from service provider into wellness consultant.

The High-Impact Talent Management Model

Bersin & Associates defines talent management as “a set of organizational processes designed to attract, manage, develop, motivate, and retain key people.” The goal of a talent management program is to create a highly responsive, high-performance, sustainable organization that meets its business targets (for more information, see Bersin 2007a).

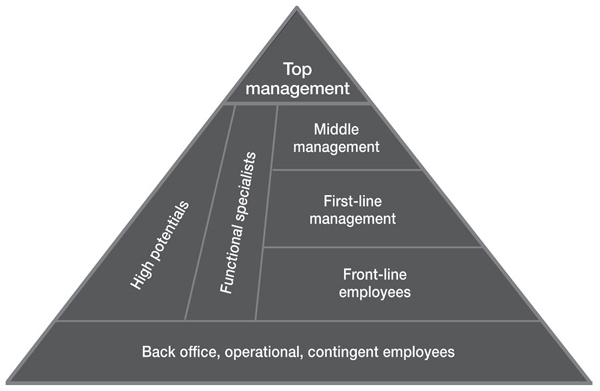

In accord with this understanding of talent management, Bersin & Associates has created a High-Impact Talent Management Model, which has four core functions (figure 2-2):

- talent acquisition, typically consisting of sourcing, recruiting, and staffing

- performance management, referring to the process of goal setting, goal alignment, coaching, manager evaluation, selfevaluation, and development planning

- succession planning and management, which includes processes like calibration and evaluation of employee potential

- leadership development.

Each of these four core people processes is both complex and highly strategic. One of the biggest changes that has occurred in the last few years is the rise of the concept of “integration.” Heretofore, many large and small organizations separated these various human resource development processes among different groups and different managers. Today, they are viewed as interrelated processes that must work together.

Bersin & Associates developed this model after interviewing many hundreds of companies. Remember that although many organizations are not necessarily organized in this way (yet), these pieces fit together into a whole. Consider five key issues, as shown in figure 2-2. First, notice that competency management and learning and development (L&D) form a platform for talent management. An organization cannot develop strong recruitment, assessment, performance management, or leadership development programs without a series of competency and capability models. These models are foundational for a strong talent management program. And our research has found that competency management does not need to be detailed and highly specific; high-level competencies in each area drive 90 percent of the value.

Figure 2-2. Bersin & Associates’ High-Impact Talent Management Model

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Second, leadership development is a critical element of talent management. Although some organizations consider it a training function, our research shows otherwise: Strategic leadership development programs dovetail with total talent management strategies—they establish leadership values and competencies, they train leaders at all levels, and they establish the rules for succession management (and deciding who will become a leader). Leadership development also drives performance management, recruiting, and other coaching skills. In today’s slowing economy, organizations are refocusing their leadership development programs and using them to build skills from the first-line manager up. In fact, many successful talent management leaders come from leadership development backgrounds.

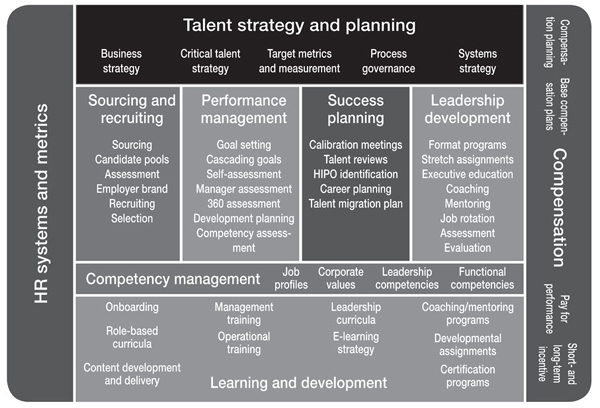

Third, what role does corporate training play in a talent management strategy? Our research shows that, ultimately, the corporate training group (or corporate university) is best viewed as a partner or supporting function to the talent management team. The reason for this is that corporate training has two somewhat tangential missions. On one hand, corporate training groups must develop, manage, and steward what we call

“talent-driven learning” programs. These programs, often considered career development or role-based programs, focus on building deep levels of competence across many stages of an individual’s career. Leadership development is this type of program. These talent-driven programs should be incorporated into the talent management strategy, because they provide stepping stones, waypoints, and development planning anchors for all employees.

On the other hand, much of corporate training falls into a second category, which we call “performance-driven learning.” These programs are shorter term, and they focus on day-to-day process changes, product rollouts, and the technical needs of the workforce. High-performing training organizations manage both types of programs together, working with line training groups in what we call a “federated” model.So, though L&D must support talent management, it must also be somewhat independent—and thus has two roles (figure 2-3).

Sourcing and recruiting, or “talent acquisition”—on the left side of the model shown in figure 2-2—is perhaps one of the most important parts of talent management, because unless the “right people” are hired, the rest of management makes no sense. Ideally, then, the sourcing, recruiting, staffing, and onboarding processes in talent acquisition should be designed and integrated with the other three areas shown in the model. Sophisticated companies (Boeing, for example) take the job roles, competencies, and proven performance measures of high performers and use this information to screen and assess candidates. In most companies, however, the staffing department is still separated from the talent management team. Though this integration is becoming more and more common, today most companies are spending their time first optimizing the areas of performance management, succession, and leadership development. Once these areas are established, they can be used for talent acquisition.

Fourth, compensation is clearly a talent management issue, but it is rarely integrated into today’s talent management portfolio. Again, the reason is mostly evolutionary: “Total rewards” or compensation is quite complex and is typically associated more with finance than with talent management. However, today’s focus on pay-for-performance, pay-forcontribution, incentive compensation, and other variable pay programs has forced organizations to integrate such functions into the design of the performance management process. Bersin & Associates’ research shows that although compensation is clearly a critical driver to organizational performance, it actually has less impact than what people may think; in most roles, compensation is a “hygiene” factor—it must be high enough to keep people engaged, but an excessive focus on compensation does not necessarily improve performance. (Of course, some roles and industries are very compensation driven. Sales organizations are notoriously “coin operated,” so their compensation structures are critical to high performance. Investment banking, real estate development, legal partnerships, and other industries also have traditionally been managed by tremendously large and complex compensation incentives. Many companies in

Figure 2-3. The Two Roles of Learning and Development

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved.

these industries actually suffer from more immature talent management processes and replace them with heavily targeted incentive compensation strategies.)

Fifth, notice the “talent strategy and planning” box at the top of figure 2-2. One of the most immature aspects of the talent management framework is the ability of organizations to actually understand the current state and plan for future talent needs. Though many companies have a good record of open head-count and hiring requirements, our research shows that fewer than 6 percent of organizations have a deep understanding of the skill and capability gaps of their entire workforce, and even fewer model these as part of their business planning process. We believe that one of the next steps in talent management will be the integration of all these processes into the business and financial planning process. In today’s economy, more than 35 percent of all companies are going through some type of restructuring. Without a strong talent planning process, these programs are difficult to implement quickly and effectively.

High-performing companies integrate these processes in a very strategic and dynamic way. Consider Caterpillar, for example. The company has centralized its talent planning and management process under the umbrella of Caterpillar University. The university is now the head of talent programs for the company and has developed a program to integrate skills planning, head-count planning, and monitoring of employee engagement and performance management into the planning process of every major business unit. Lowe’s, IBM, Accenture, and many other high-performing companies are going down this path. Once an organization reaches this level of maturity, talent management goes far beyond human resources (HR) and becomes truly an integrated business process.

It often takes many years to reach this level of maturity. Companies like Boeing, GE, Textron, IBM, McDonald’s, and Aetna have worked hard on these processes for many years, and they now credit their ability to adapt and change to integrated talent management programs.

A Business-Driven Approach to High-Impact Talent Management

Having discussed the technical aspects and history of talent management, now let us turn to the most important issue of all: how talent management drives business impact. Why does talent management matter?

The first thing one must realize is that talent management practices, which look and feel like “HR work,” real y make up the underlying infrastructure for any high-performing organization. Any business, government, nonprofit, or educational venture needs the principles of strategy, alignment, accountability, feedback, leadership, management, learning, and development. These fundamental people processes can be applied in very different ways—but if an organization ignores them, it wil ultimately fail.

At Bersin & Associates, our research has found that “enduring organizations”—those that survive over many years and through many business cycles—have one major thing in common: They realize that their ultimate organizational strength comes not from their technology, products, or patents but from their people, culture, and strategy. These companies use talent management to grow, restructure, change, and adapt to their markets. They use it to select the right candidates, promote the right leaders, and reward the right high performers. But this kind of high-level talk will never cost-justify a new system or a reorganization. So let’s look at some specific business applications of talent management strategies.

Downsizing or Restructuring?

One of today’s top business challenges is the need to downsize and restructure. Though this problem is urgent today, it is actually a continuous problem in any company. Whenever a company restructures, sells a division, or gets out of a business, some positions need to be eliminated and new ones need to be created.

With so many baby boomers starting to retire, the pool of candidates necessary for making these changes may be insufficient. Who should we let go, and who should we keep? Who would be the best people to move into newly created positions in a fast-growing business unit? Who are the people we really do not want to lose during a downsizing? How do we identify the high performers within a low-performing division or business unit? How do we identify the low performers within a high-performing business unit? Do we have clearly defined ratings and skills data to make these decisions? With an integrated talent management program, these decisions can be made quickly and with sound judgment.

Improving Performance and Engagement

Another significant challenge is finding ways to improve individual employee productivity and workplace engagement. How does one deal with such systemic issues across a broad base of employees? The solution requires a heavy focus on leadership and management development, a passion for organizational learning, the alignment of goals and a clear distinction of responsibilities, and clarity about the organization’s mission. These lofty goals are difficult to implement without defining and developing the processes mentioned above. For example, at IBM, which has transformed itself from a computer manufacturer into a leading consulting firm, people are incentivized and rewarded for sharing knowledge with each other in a highly transparent way. This cultural goal drives performance and engagement and is embedded in IBM’s leadership development and performance management processes.

An Aging Workforce and Impending Retirements

In some industries, there is still an impending shortage of workers. For example, Chevron, a highly profitable company with operations all over the world, expects as many as 50 percent of its key employees to become eligible for retirement in the next five years. The average tenure of a Chevron employee will soon drop from 15 to eight years. Though the slowing economy has slightly reduced the impact of this problem, the company sees a tremendous need to rapidly build its skills and leadership pipeline.

The only way to accomplish this is to identify the critical skills; develop successors; revamp career development programs; and implement new approaches to recruiting, onboarding, and employee development. Such programs are urgent if Chevron wants to continue its global growth and its rapid transition from an oil company to an integrated energy company.

Revamping or Improving Compensation Strategies

Today, as a result of the economic downturn, many companies are rethinking their compensation strategies to create more pay-for-performance elements. The goal here is to raise the level of employee performance through incentives, while keeping total compensation levels flat or even reducing them. Who should participate in these programs, and how should they be measured? What level of managerial discretion should be applied, and what are the criteria for making such decisions? Does the performance management process have the maturity and validity to support these decisions?

One well-known retailer implemented a new talent management program and found that more than $11 million in bonuses was handed out to store managers—with very little relationship to true employee performance. But once the new performance management system was put in place, this expense was reduced to $5 million, more than paying the entire cost of the system and the new processes it supported .

Improving Skill Levels and Enabling New Business Opportunities

Suppose your company is expanding into a new area (who isn’t, these days?) and exiting old businesses. How well do your managers understand the ability of their people to move into the new roles and perform the new work? Do you have an overall understanding of skills gaps across the organization? An integrated talent management program should quickly provide insights into these skills and provide the L&D organization with clear direction for focusing on its audience. Even better, when major business transitions occur, the program should facilitate coaching and knowledge sharing as part of key employee performance plans.

For example, when Aetna went through its massive turnaround in the mid-2000s, the company realized that many of its acquisitions were not performing well. Once it rationalized its businesses, the CEO’s first priority was to build a process to align employee skills with business needs. Over a five-year period, Aetna implemented an integrated talent management, skills assessment, performance management, and business planning approach, which built skills development right into the company’s business plan. Today, every employee has a development plan targeted toward the company’s strategic goals—and when a reorganization takes place, the company can quickly identify the right candidates for movement. Aetna today has become one of the most profitable insurance companies in the United States, which it credits largely to its integrated business and talent management process.

There are many other business drivers behind talent management. These include global expansion, rapid growth, and the acquisition of another company. Ultimately, these drivers will be very company dependent and will vary from year to year. But as you will see in the next section, talent management is far more than the solution to a problem—it is an underlying business competency.

The Four Steps in Implementing a Talent Management Strategy

Given the business challenges described above, what is the right way to go about building a talent management strategy? After talking with many companies, Bersin & Associates developed an integrated process and framework, which we’ll explore in this section.

Remember, the viewpoint here is that talent management is not a squashing together of HR roles but something quite different: applying strategic HR disciplines to your company’s business needs. Consider a simple thought: No successful business strategy can succeed without a related talent strategy. This is the essence of talent management: building a process infrastructure that supports business goals.

So how do you do this? Consider these four steps (figure 2-4):

1. Identify the business problem or problems to be solved.

2. Determine the business-related talent challenges.

3. Design the human resources processes.

4. Implement the new systems and processes.

Step1:Identify the Business Problem

The first step in the development of a talent management strategy is to clearly identify the business challenges your organization faces. What are the business goals for the next 12 to 24 months? Into what new products, services, markets, or geographies will you expand? What changes in structure or customer focus will drive your organization? What major new programs, initiatives, or restructurings must you accomplish? This information should be available to you from the company’s one-to twoyear business plan.

Step2:Determine the Business-Related Talent Challenges

Step 2 is, perhaps, the most important and most difficult one in developing a talent management strategy. What business-related talent challenges could prevent you from achieving the goals of this plan? What skills, capabilities, or head-count gaps could prevent you from achieving the goals outlined in Step 1?

In most companies, these questions are very difficult to answer. Only 6 percent of organizations claim to have a detailed understanding of their skil s and capability gaps. Ideal y, talent gaps should be readily available from line executives. In fact, mature talent management strategies wil force business leaders to create talent plans as part of their annual business plans. Once you have established your core talent management strategy, you can start asking business leaders to assess capabilities against this strategy.

In most cases, talent challenges are somewhat obvious (a lack of nurses for health care providers, high turnover level in sales, low skills in manufacturing, and so on). But ideally, you need to do modeling—comparing growth plans with worker productivity plans, for example—to see where expected gaps will develop. In other cases, you will find information readily available in other HR departments: current gaps in performance, high levels of turnover, changes in workforce demographics, or low levels of engagement or commitment. This information should make up this second part of your talent plan.

Figure2-4.The Four-Step High-Impact Talent Management Strategy

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

When Starbucks was expanding, for example, it careful y assessed the number of baristas and store managers required to succeed. Using established turnover rates by store location, its planning staff looked at the local geography to make sure the required labor pool was available to meet expansion needs. Sometimes this process told the company that it had to relocate key managers. Today, as Starbucks cuts back on its locations, it uses this same planning process to predict attrition and plan store closures.

When the military contractor Raytheon started planning its 10-year plan through 2015, it found a pending gap of 25,000 or more technical professionals. The combination of retirements and growth in national defense programs surfaced a tremendous undersupply of technical professionals at various locations. The ultimate solution was an integrated program of career development, relocation of work to new locations, and technical succession management, which required the development of a new technical career model, competency assessment, and implementation of talent management software .

Step 3: Design the Human Resources Processes

Step 3 in developing a talent management strategy is designing (or redesigning) the HR processes required to meet staffing and talent gaps. This is the step that many HR practitioners enjoy the most. Do you need an improved university recruiting program or a new employer brand to attract younger workers? Do you need a career model for the impending gaps in the technical pipeline? Or perhaps the process for employee evaluation should be scrapped and then re-created? We will discuss performance management later in this chapter, because it is, perhaps, one of the most central talent management processes.

In this step, you, as an HR or L&D professional, must think through your options in creative ways. In almost every case, you probably have many HR processes in place—but they may be old or ineffective. How can you improve them to meet the new talent needs? How can you further enlist line managers to help you redesign or streamline the process to gain greater acceptance and value? Many HR professionals design complex, highly sophisticated processes that are difficult or impossible to implement. Bersin & Associates’ research in performance management, for example, shows that organizations that tweak their process over many years end up with simpler and simpler approaches. In most cases, a simple but highly strategic process works better than one with many steps and options.

Most HR processes depend on an underlying job competency model, career model, and set of leadership competencies. Before you rush into designing new processes, make sure these fundamental pieces are up to date, relevant, and aligned with the company’s strategic direction.

Step 4: Implement the New Systems and Processes

The fourth and final step in developing a talent management strategy is implementing the new processes and systems. Many companies believe that software is their first step, and they try to start here (and most HR software vendors push this as well). The problem with this approach is that it is nearly impossible to configure, implement, and roll out talent management software without clear, strategic, well-agreed-upon processes. Remember that the best talent management strategies and programs do not necessarily rely on technology. Many of the world’s best-managed companies implement world-class management and talent processes using paper-based forms and tools. Though paper is certainly not the most reusable and sharable approach, we find it is best to use technology as a tool for solving a problem, not as a tool looking for a solution.

Consider the performance management systems implementation at Teletech, one of the world’s largest and most profitable cal center outsourcing companies. The company had a strong culture of operations management for many years and then decided to implement a new performance management system to help corporate managers better assess skil s gaps on their teams. The business case focused primarily on process automation.

The project leader, a senior HR leader at corporate headquarters, found tremendous resistance to the project because it was not anchored in a fundamental business problem or business change. In the first nine months of the performance management process, the system went through several major redesigns, and the overall implementation could take two years or more. Though we are big fans of HR software, remember that talent management software is not talent management. If you first focus on the problem, processes, and governance, systems implementation can go quickly and successfully. But failure to do so may lead to significantly different, and less pleasant, results.

The Governance of Talent Management

No HR process is more interlocked with business, leadership, IT, and HR than talent management. Remember that ultimately the “owners” of talent management are not HR but the business leaders themselves.

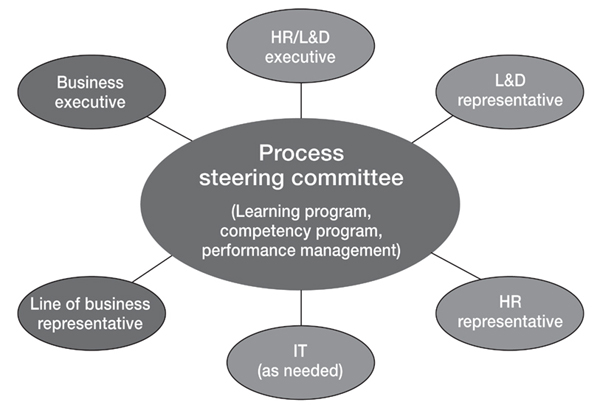

If you tel the organization that “talent management is coming from HR,” you may undermine your entire program. The purpose of the talent management program is not for HR alone to gain information but rather to enable the business leaders, managers, and employees themselves to make better decisions. The program wil clearly have many benefits for HR, but ultimately the processes and systems you implement must be “owned” by line management. This is why the proper governance of talent management processes and program plays such a critical role (figure 2-5).

Look at the elements of figure 2-5. There are many stakeholders who should be involved in the strategy, design, and implementation of the talent management program—including line business managers (at least one from each major division or geographic owner), information technology, L&D, and at least one major business executive sponsor.

Consider, for example, the talent management program at Caterpillar, a large and complex global manufacturer. Each geographic unit of Caterpillar across the world is responsible for its own profit-and-loss statement and has both the authority and responsibility to implement strategies for its local market. The company, however, takes organizational learning, individual learning, and talent management very seriously. The organization currently called Caterpillar University is responsible for global development planning and talent management processes throughout the company. This includes performance management, succession management, and development planning.

To implement global standards while enabling regional control, Caterpillar University works closely with the senior leaders of each business unit. These leaders create common talent plans as part of the annual planning process, participate in the university’s executive committee, and assign senior representatives to work with the university on detailed process design. We call this a “federated” organization model—and it works very well for large organizations .

These people will be the ones who “carry the torch” for the leadership development program, the performance management process, employee development programs, and the new HR portal. They should be consulted regularly for input on program design and project timelines. Remember that talent management programs only succeed when managers adopt them, which leads us to the next topic: business ownership.

The Business Ownership of Talent Management

Who do you think really owns the talent management process—the director of talent management or the vice president of HR? Neither. Ultimately, talent management is not an HR initiative at all but is part of a business strategy. Bersin & Associates’ research clearly shows that if you want the process to succeed, it must be owned by the business leaders in each major division of your company. Your job as an HR or L&D leader is to be the process “steward,” consultant, or change agent.

Figure2-5.The Governance of Talent Management

Enlist business leaders to create adoption, not compliance

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Consider the information shown in figure 2-6, captured from Bersin & Associates’ Talent Management Factbook, which distills research on more than 1,000 companies in 2008 (for more information, see O’Leonard 2008). This research asked companies to characterize their talent management programs into four possible approaches: those owned by a top executive, those owned by HR, those owned by the line of business, and those delegated fully to business managers. In figure 2-6, the percentages given show the relative improvements (or negative impact) in the area listed in the left-hand column for each of the governance models, which are listed across the top. For example, companies that delegate leadership development to individual business areas show a 22 percent reduction in business impact from the average—and those that have CEO sponsorship show a 14 percent improvement over the average.

As figure 2-6 clearly shows, top executive ownership drives higher outcomes than the other models. The reason for this is somewhat obvious: Talent management at its best should influence the behavior of every manager in the company in some way. If managers in your organization do not see the implementation of these processes as part of their jobs, you will find spotty implementation and a lack of engagement.

Consider these statistics: Although approximately 66 percent of organizations claim to have some form of corporate performance management, almost 75 percent told Bersin & Associates that their managers are undertrained or insufficiently focused on employee assessment, coaching, feedback, and development. According to anecdotal research, at least half of new managers receive little or no training in supervisory or management techniques when they take on this new role. (For more on these data, see Levensaler 2008a, 2008b.)

If line managers do not believe that performance management is a major part of their jobs, they will look at the associated process as just one more HR compliance program. And thus, though they may comply with the program, they may not commit to achieving its goals. Organizations need to structure their talent management processes so that line

Figure 2-6. The Positive or Business Negative Impact of Four Approaches Relative to Talent Governance Models

Align with the business first—all business challenges also have talent challenges

Note: The “business impact” referred to here refers to the self-reported business results from this particular process or area. For the thousands of respondents, this data is highly differentiated and correlated.

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

managers and executives do their job because they see its value, and this demands top-level executive support.

The Four Key Elements of a Talent Management Strategy

As organizations implement more integrated talent management strategies, they start to see how performance management, competency management, leadership development, and corporate L&D fit together. Let us briefly examine several key issues for each of these areas.

Performance Management

In many ways, performance management is the core of talent management. As we like to remind people, performance management is management. This process, which is often described as the annual appraisal or “performance management process”—PMP—is understood today by organizations as establishing the foundation for much of the rest of talent management.

Ideally, performance management should be built around an organization’s culture—in some organizations, there is a rigorous, competitive nature to work; in others, there is a highly collaborative, innovative approach. Bersin & Associates’ research has shown that, broadly speaking, organizations fall into one of two camps: the competitive assessment approach, or the coaching and development approach. Of course, all organizations use both to a degree.

When asked to select which they believe best represents their culture, approximately 59 percent of organizations rate themselves as coaching and development related, and 41 percent focus more on the competitive assessment approach.

Our research identified seven separate practices within the defined process of employee performance management:

- goal setting

- goal alignment

- employee self-assessment

- management assessment

- competency analysis and discussions

- 360-degree or peer assessment

- development planning.

As HR professionals know, each of these practices is complex, demanding thought and sometimes training.

Unfortunately, the whole area of performance management is constantly changing; when we interviewed organizations to understand their practices, more than 70 percent were “changing something,” and the changes tend to be widely varying. The reason for this is that, over time, performance management processes tend to start on the left of the chart (with a highly competitive process) and move toward a process focused on coaching and development, following the maturation of a business in general. When the company is small, people can be held directly accountable for results. But as the company grows, roles become more complex, and the ability to coach and develop people becomes more important. We also see a shift based on the business cycle: When companies go through tough times, their process becomes more rigorous and competitive; when they go through times of growth, they focus more on development and coaching. (For more on this data, see Levensaler 2008a, 2008b.)

Ultimately, this process is a vital foundation for talent management because it sets the rules for discussions between managers and employees, it establishes competencies and processes for evaluation, and it produces performance and potential ratings used for leadership development, compensation, and succession management.

Competency Management

Organizations struggle with competency models in many ways. Bersin & Associates’ research uncovered two key findings. First, you cannot implement a sound talent management strategy without a clear understanding of your organization’s core competencies, leadership competencies, and some level of role-based competencies. And second, it is not necessary to overengineer competency management at all—in fact, the process can be quite simple.

As figure 2-7 shows, there are many types of competencies: core values, effectiveness competencies, functional competencies, and leadership competencies. Ultimately, you must think about the purpose of a competency model before you build it: A leadership competency model is used for leadership assessment and development; a functional competency model is used for training associated with a particular job or business function; core values are used for performance management and coaching.

One key best practice that Bersin & Associates found in our research is that for many highly successful companies, fewer is better. Organizations like GE, American Express, IBM, and Coca-Cola, which have been evolving their performance management processes for years, simplify their competency models to eight or fewer competencies. Though many

Figure 2-7. Types of Competencies

© 2008 Bersin & Associates.All rights reserved. Used with permission.

functional competencies are useful for developing training programs, they are usually of little value in real managerial performance management and leadership development.

Our research also shows that although there are many excellent competency models and books, organizations gain the greatest benefits from competency management when they focus on identifying the unique, culture-specific competencies that drive their organization. (Bersin & Associates’ research on the effective use of competency models is available at www.bersin.com.) When we looked at the in-depth competency models in place in eight major corporations in financial services, technology, retail, and manufacturing, we found that the best-performing companies in each industry had markedly different types of competency models in their performance management programs. More successful companies tended to focus on higher-level values, such as quality, communication, and leadership, while less successful organizations tended to focus on hygiene competencies like safety and operational skills (for more information, see Bersin 2007b).

We have found that companies succeed by focusing on one of four underlying business strategies: product leadership, low cost, customer intimacy, and service leadership. In each industry, high-performing companies can succeed by focusing on any of these four business strategies. For example, in the retail coffee marketplace, Peet’s is a product leader, McDonald’s and Dunkin Donuts are low-cost leaders, and Starbucks is the leader in customer intimacy. As you can easily imagine, the competencies required of a high performer in each of these companies may be quite different. Remember that the value of your organization’s competency model is its ability to reinforce and integrate your company’s unique strategy into the everyday life of every employee and manager.

Ultimately, the development of a competency model for leadership and performance management is a highly strategic part of talent management and must be done early and with a strong level of executive support.

Leadership Development

Though many organizations view leadership development as another set of L&D programs, in reality it plays a far more strategic role. As we all know, leaders make organizations succeed: They hire people, define strategies, implement programs, and set the organization’s culture. Only by developing and codifying leadership can an organization grow and thrive over time.

Our research shows that organizations fall into four stages of maturity with regard to leadership development, with the relative percentage of companies at each stage shown in figure 2-8:

- strategic leadership development

- focused leadership development

- structured leadership training

- inconsistent management training.

Many talent management leaders have a background in leadership development. Without strong leadership development, it is very difficult to implement performance management, succession, and many of the other parts of a strategic talent management program. Not only doesleadership development feed the rest of the program, but it is one of the most important elements of a business-driven HR organization.

As figure 2-8 illustrates, most companies still focus on leadership as a subject within management training programs. Though training for new managers and supervisors is important, these are questions to ask: What type of managers do we want? How can we reinforce our culture, principles, processes, and behaviors? Today, more and more organizations realize that to do this, there must be a strong commitment from top executives—with leaders sponsoring the program, speaking at courses, reviewing and selecting leadership candidates, and establishing program strategies.

One example of the power of leadership development is Hewlett-Packard’s dramatic turnaround. When Mark Hurd, the new CEO, started at the company in 2004, he found a highly innovative organization that had lost its ability to focus, execute, and hold itself accountable. He brought a new managerial focus on execution, growth, and profitability. These three principles were developed and driven across all levels of executives using a powerful new leadership development program. We at Bersin & Associates believe that all strong talent management strategies must focus heavily on the principles and practices of leadership development.

Figure 2-8. The Four Stages of Leadership Development

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The Role of Learning and Development

The final element of talent management is the role of corporate L&D. The concepts of integrated talent management have entered the marketplace at the same time many companies are trying to rationalize and consolidate their L&D spending. Thus, one of the big questions companies face is whether or not corporate L&D should be part of the talent management organization.

The right answer is “kind of.” Ultimately, corporate or departmental L&D organizations have two roles: the implementation of what we call performance-driven learning (programs that deal with new products, processes, and systems) and talent-driven learning (programs that develop deep levels of skil s across an entire range of responsibilities in a role). A product rol out would be a performance-driven learning program, and leadership development or sales training would be a talent-driven learning program.

Our research shows that the L&D team must balance its resources so that it doesn’t go 100 percent in either direction. If it focuses too heavily on performance-driven learning, it does not have the time or resources to focus on key talent development programs—and if it focuses too heavily on talent-driven learning, this could lead the organization to build separate, disconnected functional training groups.

In the end, Bersin & Associates has found that L&D is a critical foundational or supporting element of talent management. Organizationally, it is often best for L&D to report to a chief learning officer or director of training and then partner with the vice president of talent management. Organizations that move the L&D team under the talent management leader must make sure that L&D investments are not overly focused on talent programs. In this type of organization (Caterpillar is a good example), the talent management leader must take on a broader and higher-level role, in which all learning and development activities are seen as necessary and valuable.

One important factor to consider in the design and implementation of an L&D strategy to support talent management is that career development programs are highly strategic and important parts of today’s talent management processes.

Figure 2-9 shows the business value (measured on the left) of a talent management program for more than 1,000 organizations, relative to the organization’s fundamental model for career development. On the far left-hand side of the figure are organizations that implement the “manage your own career” approach. These companies expect employees to find their next jobs, plot their career strategies, and create their own development plans.As we move to the right, we have organizations where the manager takes on this responsibility. In these companies, managers are given tools, models, and coaching on how to help employees plan their careers and create development plans. On the far right, we see organizations that try to do this at the business unit or enterprise level.

As the data show, the impact goes from negative on the left to positive on the right, with the greatest value (or slope of the curve) at the managerial level. What this is tel ing us is perhaps obvious: Career or professional development must be focused at the managerial level or higher. If we expect people to find the right jobs or develop the right skil s to achieve individual and organizational goals, we must create models and programs that enable managers and business units to drive career development activities.

One senior vice president of HR at a global defense and aerospace contractor said this: “We used to have the ‘pinball’ model of career development. People bounced around from job to job—some of them bounced out of the machine, and we just kept pumping more balls into the machine. The problem is that many of our best people went out the bottom and, due to impending retirements and demographic changes, we have fewer and fewer technical professionals available to shoot into the machine. We need a more ‘deterministic’ model to moving people into the right roles to help us grow.”

Once an organization realizes that career development is part of its business strategy, the work to build these programs and models will fall upon L&D.

The Importance of the Organizational Culture

As more and more organizations seek to understand how talent management can be used most strategically, one of the most important dimensions to consider is culture. As many researchers have found (Schein 2004; Cameron and Quinn 2005), organizational culture both creates

Figure 2-9. The Higher Value of a Centralized Approach to Career Development Programs

© 2008 Bersin & Associates. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

and reinforces behavior. Many of the processes and programs that make up a talent management strategy (particularly leadership development and performance management, but also training) must be highly customized and adapted to align with an organization’s culture.

As Edgar Schein (2004) states in his research, people in companies do not “see the culture” any more than fish “see” the water in which they swim. Culture defines the underlying assumptions and beliefs that make an organization work.

If your company has a highly competitive environment that thrives on concepts like market leadership, competitive analysis, and growth at any cost (similar to GE), your talent management program must reflect and reinforce this culture. In these kinds of companies, talent management focuses on building organizational and process savvy, and on moving people around from role to role.

However, if your organization succeeds through deep levels of innovation, creativity, and product excellence (Qualcomm and Apple come to mind), your talent management program must reflect this culture and focus on building deep levels of skill, collaboration, and communication of technical excellence—focusing on a more “vertical” or “function-specific” talent management strategy.

And if your organization has a culture of a client intimacy or service (IBM comes to mind), your talent management program may focus on helping people build customer-focused teams, industry expertise, and contacts, and creating an “open listening,” customer-centric set of people processes.

Recognition of and respect for an organization’s culture is a critical element in a talent management strategy, because any program or process that does not fit into and reinforce this culture becomes underused, poorly regarded, or undervalued.

The Bottom Line

Today’s integrated talent management strategies are an important and exciting way to help HR and L&D professionals add value to their organizations. As an HR or learning leader, you must remember that your job in talent management has two parts: On one hand, you are a highly specialized HR and L&D expert—armed with expertise in talent programs, processes, and systems—with a focus on consulting, process design, communications, and change management. On the other hand, you must become a business leader. You must engage with business managers to help configure, customize, tailor, and refine talent management strategies so that they reflect your organization’s business strategies and culture. In this latter role, you have the opportunity to reshape the company and the way it does business.

One of the biggest challenges for all HR and L&D leaders is to stay aligned, relevant, and valued by the business. HR has a legacy of jargon, best practices, and traditions that many businesspeople neither understand nor care about all that much. Talent management, if executed with the principles outlined here, will give you a real seat at the table and enable you to add value to your organization in a highly strategic way.