Chapter 4

McDonald’s Talent

Management and

Leadership Development

Neal Kulick, Vice President,

Global Talent Management

(Retired as of July 2009)

What’s in this chapter?

- How talent management is structured at McDonald’s

- A step-by-step explanation of how McDonald’s built its talent management capability

- The impact of the talent management approach on McDonald’s

McDonald’s Corporation is a $23-bil ion-plus global business with more than 31,000 restaurants in 118 countries serving more than 55 mil ion customers each day. Founded by Ray Kroc in 1955, at the tender age of 54, McDonald’s has been in business for more than 53 years. It has had a long track record of outstanding and steady growth and, since going public in 1965, has provided outstanding total returns to its shareholders. McDonald’s more recent history, specifical y from 2000 to 2009, has been particularly interesting for several reasons, each of which is explained below.

For the first time in its history, the business declared a loss (for the fourth quarter of 2002). In spite of significant growth in new restaurants and huge investments in capital to support this growth, the business was not earning sufficient returns on investments. Additionally, it was clear that restaurant operations, the hallmark of McDonald’s success, were suffering and that quality, speed, and cleanliness performance had slipped. Our customers noticed, and they told us about it.

McDonald’s stock price hit a low of below $13 per share in March 2003, and in December of that year the board of directors made the decision to replace the CEO. His replacement, James Cantalupo, 60 at the time of his appointment, had recently retired from the company after a long career in finance and international operations. Appointed as his COO was another long-time McDonald’s executive, Charlie Bell, who started as a McDonald’s “crew” member in Australia and progressed rapidly in the business. Charlie was only 43 when appointed as COO. The board charged Cantalupo and Bell with “righting the ship”—getting McDonald’s back on track and turned around.

In 2003, they, along with other key business leaders, crafted a turnaround strategy that is stil in place—labeled McDonald’s “Plan to Win.” This global strategy, which has been adopted in every market, essential y laid out five areas of focus—known as the “five Ps”—and standards for each:

- people

- product

- place

- price

- promotion.

Each market, working under this common Plan to Win framework, was able to customize and localize its specific approach, as long as the market remained within the framework. This governance philosophy was labeled freedom within a consistent framework, and it, too, is still in place today as McDonald’s overall governance philosophy.

McDonald’s Talent Management and Leadership Development McDonald’s went from its historical focus of building new restaurants as the primary growth strategy to getting better, not bigger. The growth of new restaurants was scaled back almost completely so that the overwhelming focus could be on improving the existing 30,000-plus restaurants already in the system. The other growth strategy of acquiring new brands to scale (including Boston Market, Chipotle, Pret à Manger, Donato’s Pizza, and the like) was also reversed, because it was determined that these new brands would take too long to scale in a meaningful way and, more important, they were a distraction to the management team and others in the system. The bottom line was that the focus was back on McDonald’s restaurants to grow revenue significantly with better quality, service, speed, cleanliness, value, and new products.

Tragedy struck McDonald’s in 2004 in a way that few other companies have known or likely will experience. The first tragedy occurred in April 2004, at McDonald’s owner-operator convention in Orlando. Early in the morning of the first day of the convention—which was attended by more than 15,000 owner operators, employees, and suppliers—Jim Cantalupo suddenly died of a heart attack in his hotel room, only a few hours before he was scheduled to give the opening keynote speech. Needless to say, this postponed the opening session on Monday morning, and the board of directors had an emergency meeting to appoint Charlie Bell as the new CEO. The convention went carefully forward with Bell and other key executives leading with remarkable skill and sensitivity, moving on in a way that enabled everyone to express their emotions with regard to the tragedy and support one another, but still go forward with the most important business at hand.

The tragedies would not end with the loss of Cantalupo. Shortly after Bell returned to Chicago the week following the convention, he was diagnosed with colon cancer. He battled the cancer valiantly but had to resign in December 2004 and died in January 2005. The board named Jim Skinner, a former “crew kid” with more than 30 years of service, who had progressed to his then-current role of vice chairman, as the new CEO.

Skinner wasted no time in establishing his priorities and communicating them to both the board and to his entire leadership team. He launched his CEO agenda with three priorities. One of these was talent management and leadership development. It was clear that the tragedies suffered by McDonald’s, with the loss of two CEOs to illness within a 12-month period, influenced his priorities, for the importance of having a deep internal pipeline, and maintaining it going forward, was never clearer to him or the board. McDonald’s received a great deal of positive press for its ability to have a deep pool of executive talent ready and able to step up to the CEO role in a short time. After all, Skinner was McDonald’s fourth CEO in a 24-month period. And there have been only seven CEOs in McDonald’s entire history.

As of this writing, in December 2008, McDonald’s has had an incredible run of success. The company has experienced 68 consecutive months of positive comparable sales (that is, improvement in sales for a particular month relative to the previous year’s same month). This is the longest positive run in McDonald’s history, and the stock price hit an alltime high in September 2008. It has been one of the few stocks in the Standard & Poor’s 500 that has managed to maintain its value during the economic crises of 2008–2009. In 2008, McDonald’s served 58 million customers a day!

Expanding Talent Management to the Leadership Level

McDonald’s has had a long history of focusing on its people and on talent. Most of this history, until recently, has focused on the talent in the restaurants (crew and management). With more than 1.5 mil ion employees wearing a McDonald’s uniform worldwide, people have been and always will be at the center of McDonald’s success. Ensuring that al restaurant staff are properly trained and motivated is key. To accomplish this, Hamburger University was established in 1961 as the training center for al restaurant and supervisory staff employees. HU, as it is known, is based in Oak Brook, Il inois, at Corporate Headquarters, but it has seven regional branches throughout the world. Approximately 5,000 students attend HU each year, and since its inception there have been more than 75,000 graduates. McDonald’s focus on talent management was reassessed in 2000 by the then-chairman/CEO, Jack Greenberg, who realized that the business 72

McDonald’s Talent Management and Leadership Development was struggling in the marketplace and was concerned that there was not enough focus on developing McDonald’s leadership talent. He believed that the time had come to put much more emphasis on developing leaders at McDonald’s and wanted to form a new organization to focus on both succession planning and leadership development. This new organization was funded and established in July 2001 and charged with building a succession planning and leadership capability to ensure that McDonald’s would have a high-performing leadership team in place both “today and into the future.”

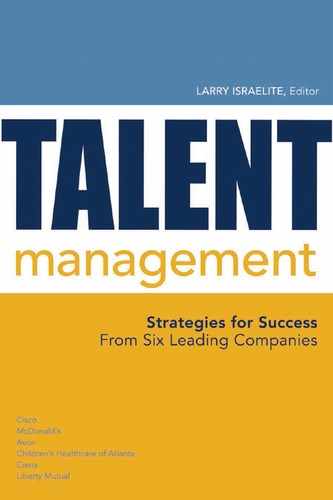

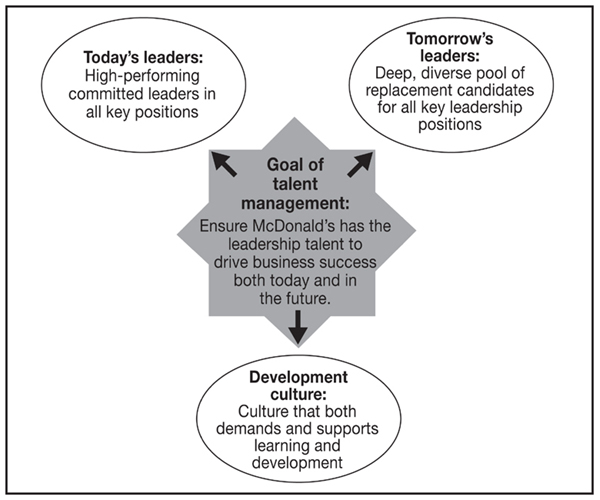

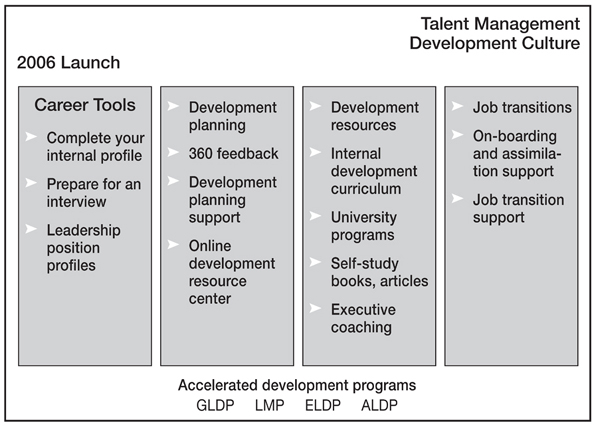

Figure 4-1 shows the message map that was developed to communicate this new organization’s overall goal of talent management (center) and the three subgoals. Figure 4-2 describes the four major process areas that the organization has in focus.

Taken together, these four areas—along with compensation/benefits, which remains as a separate organization but is within human resources (HR)—define what is now called talent management at McDon-ald’s. Building a capability and capacity for these four key areas has been the focus of the organization since its inception in 2001.

Figure4-1.The Goal of Talent Management Tomorrow’s

Figure4-2.The Scope of Talent Management

What follows are some details about how this capability was built and what has been accomplished. We’ll also look at initiatives that fell short and at what could have been done differently and, presumably, better. This chronology occurred, as stated previously, across the tenure of four different CEOs in this short seven-year time frame.

Step 1: The Starting Point—Fixing the Performance Management System

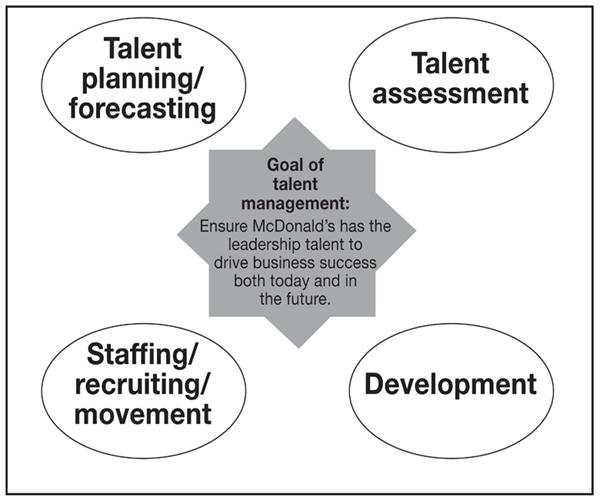

Until 2000, McDonald’s performance management system seemed to work well. At least it was making a lot of people happy in that the distribution of ratings, especially among the top leadership team (top 200), was significantly skewed to the positive. The ratings for 2000, using the five-point scale in use at the time, are shown in table 4-1. At this time, the business was performing extremely poorly, and the stock price was declining steadily. A total of 38 percent of these officers were rated as “ready now” for advancement, and another 60 percent were rated as “ready future.”

Table4-1.Ratings for McDonald’s Performance Management System, 2000

| Rating | Percent Receiving the Rating |

| Exceptional | 60 |

| Outstanding | 38 |

| Good | 2 |

| Needs improvement | 0 |

| Unsatisfactory | 0 |

Without differentiating between individuals on performance and potential, there was no way to install a succession planning process at McDonald’s. Therefore, it was decided that it was time to change the culture at McDonald’s from one of “entitlement” to one of “earning.” One aspect of this change was to fix the performance management system. These significant changes were made and implemented, effective in 2002:

- Moved from five to three rating categories, with new rating labels.

- Established target rating distributions of 20 percent in the highest category, 70 percent in the middle category, and 10 percent in the lowest category, as a way of reducing rating inflation.

- Added demonstrated competencies to the evaluation criteria, in addition to simply assessing performance against goals, so that ratings were based not only on what was accomplished but also on how it was accomplished.

- Established calibration roundtables for performance and potential assessment.

- Aligned compensation systems to ensure that pay differentiation matched performance differentiation.

The decision was made to introduce the new performance management system at the officer level so that the top 200 leaders would personally experience the new process before it was implemented with their teams. As expected, the first year resulted in a lot of anguish in that a high percentage of officers received performance ratings in the middle category (significant performance). This was the first time in many, if not most, of their careers that they had been rated less than outstanding or excellent! Fortunately, the shock wore off in time for the new system to be implemented globally over the next few years. The new performance management system resulted in clearly differentiated ratings, as illustrated in figure 4-3.

There were several “lessons learned” related to changing the performance management system:

- You can’t do talent management unless there is a performance management system in place that clearly differentiates both performance and potential.

Figure4-3.Performance Rating Guidelines

- You don’t move to the 20/70/10 distribution guideline without upsetting people, but the good news is that they wil get used to it!

- Aligning compensation is critical.

- Starting implementation at the top will help get support for full implementation (misery loves company).

Step 2: Establishing a Talent Management Plan Process and Review

In 2002, once McDonald’s had a performance management system that clearly differentiated on performance and potential, we could begin to assess the depth and diversity of our talent pipeline with much greater confidence. To accomplish this, a Talent Plan template was developed as a guide for every major business unit (area of the world) and every major country to utilize. This template laid out what was expected in the Talent Plan and provided samples and illustrations to support it.

The key elements of the Talent Plan were

- forecast of leadership requirements tied to the business strategy for that business unit

- assessment of the performance and advancement potential of each member of the current leadership team

- identification of backups and feeder pools for all key leadership positions

- if replacement gaps existed, an action plan to close the gap

- diversity analysis and an action plan, with the general rule that diversity improvement should occur year over year

- a retention strategy for top talent

- a leadership development strategy for the business unit and individual development plans for key talent.

Talent Plan reviews were established at the senior management level on an annual basis. The CEO met with each of those reporting directly to him in the April–May time frame to review and discuss his or her talent plans in detail. Similarly, senior leaders reporting to the COO also had their plans reviewed. HR’s leadership was present during these reviews, but the meetings were led by the senior leader, not the HR leader.

These Talent Plan reviews were meant to be iterative and based on discussion. The goal was for senior managers to report on the strengths of their leadership teams today and the depth and diversity of their leadership pipeline. During these sessions, many critical issues were discussed with the CEO and/or COO, who provided their viewpoints and insights.

To ensure that this planning process was tied to meaningful metrics, five key goals were established, although it was not expected that all these goals would be met in the initial years. The goals were as follows:

- A total of 95 percent of the current leadership team would meet or exceed their performance objectives.

- A total of 100 percent of lower performers would be on improvement plans, with dates to either “improve or remove” them from their roles.

- A total of 90 percent of the key leadership positions would have adequate succession candidates, including at least one ready now and one ready future candidate.

- There would be 95-percent retention of the top talent, including both the highest performers and high potentials.

- There would be written development plans for all those with high potential.

The first time these plans were completed and reviews took place, the results and metrics were not encouraging:

- More than 50 percent of the key leadership positions lacked adequate backups.

- There was a clear need to improve diversity, especially gender diversity.

Based upon these findings, it was clear that McDonald’s needed to take steps to accelerate the development of the feeder pool to build up the depth and diversity of the next generation of leaders. This would be the next step in the evolution of McDonald’s talent management capability.

McDonald’s learned these lessons from the establishment of this Talent Plan process:

- The first iterations of a Talent Plan will be a bit disappointing—it takes a few years before the plans reflect sufficient quality and detail.

- There is a need to reinforce the strong linkage required between the business strategy and the Talent Plan, because this linkage may not be made as naturally as one might expect.

- It is important to establish a disciplined follow-up process to the plans so that commitments that are made within the plans are tracked and leaders are held accountable.

- It is useful to start at the top of the organization and then work your way down through all levels.

- Goals and metrics are important, but be careful not to put so much emphasis on them that you may encourage managers to “stretch the truth.” (Example: If a metric is the percentage of leadership positions for which there are strong backup candidates, there might be a tendency to list names of individuals as backups who are really not as strong as required.)

Step 3: Designing Accelerated Development Processes to Build the Depth and Diversity of Feeder Pools

With the goal of increasing the depth and diversity of the replacement pools for McDonald’s top 200 leadership positions, an accelerated development program was designed and piloted in 2003. The program was titled the Leadership @ McDonald’s Program (LAMP). The program was global, with 24 high-potential directors/senior directors assessed as having the potential to assume a “top 200” position within the next three or four years. Participants came from Europe, Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East, Latin America, and the United States, with a wide variety of functional backgrounds. From a diversity standpoint, there were 40 percent women and 39 percent minority participants representing 11 countries.

Candidates for LAMP were nominated by the senior leader of their respective organization and screened and admitted into the program by the CEO. Criteria were provided to guide the nomination process, including the goal to nominate a diverse group of candidates so that we could achieve our goal of building up the diversity of our feeder pool. That said, no specific numerical targets were set for diversity. Fortunately, and to the credit of the senior leaders who nominated candidates, our first class was extremely diverse.

The goals of LAMP were to

- broaden participants’ understanding of our business, from a global and cross-cultural perspective

- enhance leadership skills, with a special focus on those skills and perspectives required of a more senior leader, both today and into the future

- build relationships and a strong network among the participants

- provide exposure to business issues and best practices outside McDonald’s

- reinforce the commitment to continuous learning and selfdevelopment

- provide senior leaders with the opportunity to get to know the participants better via active participation and dialogue during the sessions

- provide special recognition for participants via their being nominated to participate in LAMP, hence building their level of organizational engagement.

LAMP participants went through a personal orientation with a member of the Talent Management Team. The purpose of the orientation was to provide each participant with a realistic picture of the program, including the time commitment. Given that LAMP participants were expected to continue their normal work assignments during the duration of the program, LAMP was a significant overlay on their already busy schedules. It was expected that their participation would take approximately 25 to 30 percent of their time.

LAMP was primarily designed using McDonald’s internal resources, but there was a strong partnership with an outside consultant/facilitator who worked shoulder to shoulder with the internal staff both to design and execute the program. The combination of internal and external thought leadership proved to be outstanding, as the program design was unique for McDonald’s, reflecting outside thinking and experiences, but also relevant and appropriate to the company’s culture.

The key elements of LAMP included

- a nine-month program with six classroom sessions of three to four days each

- a third-party assessment and a 360-degree (boss, peer, direct report) survey feedback

- detailed personal development plans based on the results of the assessment and feedback

- executive dialogues at every session

- coaching, both by the program facilitators and by peers

- leadership modules, focused on enabling program participants to step up to greater leadership roles

- a university experience, comprising two weeks at the Thunderbird School of Global Management, as part of a consortium with other major companies

- an action learning project

- a presentation to the senior leadership team.

The initial LAMP pilot was extremely successful. The feedback from participants was outstanding, and follow-up with their managers indicated both increased capabilities and extremely strong commitment to their own continuous development. Many LAMP participants took the lessons they learned from the program and applied them on the job, including doing a much better job coaching and developing their own direct reports.

One measure of the success of LAMP was the fact that the area of the world (AOW) presidents for Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and Africa, and the president for Europe asked the Talent Management Team at Corporate Headquarters if they would do a “LAMP-like” program just for their AOW. They felt that their need to build their own feeder pools was so great that they needed to give more of their people a LAMP experience than would be possible if the program was done only on a global basis with a fixed number of participants. By doing a similar program in their own AOW, they could accelerate the development of 15 to 20 people with high potential rather than the three to five if the program remained global.

When both AOW presidents offered to totally fund their program, the Talent Management Team was excited to partner with their HR leaders to build and deliver such a program. In 2004, three separate accelerated development programs were in place: the European Leadership Development Program (ELDP); the Asian Leadership Development Program (ALDP); the Middle Eastern and African Leadership Development Program; and LAMP Americas, which now focused on the United States, Latin America, Canada, and the corporate office.

If we fast-forward to 2009, here are some statistics related to these three programs:

- Since 2003, there have been four LAMP sessions, three ELDP sessions, and three ALDP sessions, with a total of 200 graduates.

- Women made up 42 percent of the participants in all programs, and 36 percent of the participants have been from minority groups (counting only participants from the United States, where minority group definition is tracked).

- Participants have represented 45 different countries.

- A total of 37 percent of the graduates of all programs have been promoted.

By most standards, these statistics demonstrate that these accelerated development programs, implemented in response to significant gaps in the replacement pools for McDonald’s top 200 positions, have successfully filled those gaps. Further evidence of this fact is that McDonald’s now has moved the number of key leadership positions for which we have strong backups from 50 percent to more than 80 percent in the five-year period since these programs were first piloted.

The LAMP efforts have a strong pull and a strong brand within McDonald’s. Graduates of the LAMPs, once they are promoted, are anxious to identify potential leaders they can send to these programs, and it is considered high recognition to be selected to participate.

Several important lessons have been learned as a result of designing and delivering accelerated development programs to grow top leaders:

- Start small, with a pilot, and establish a brand.

- The length of the program matters. Having the program conducted over a several-month period (in this case, eight to nine months) provides much more sustained attention to development not possible when a program is “one or two weeks and done.”

- Action learning projects have to be chosen carefully and have to have strong sponsors. Also, the projects need to scaled correctly and be relevant to leadership.

- Programs in different areas of the world need to be shaped and customized accordingly. This can be done while still keeping the core elements of the program intact.

- Be careful not to put too much focus on those with high potential, thus making other managers feel that they are not valued.

Step 4: The Launch of the McDonald’s Leadership Institute

In 2006, a few years after McDonald’s began delivering accelerated programs in three areas of the world, it was decided that it was important to address the development needs of the entire leadership population, both those with high potential and others. For this reason, and because McDonald’s wanted to send a clear and loud signal that leadership development was one of its highest priorities, the decision was made to launch the McDonald’s Leadership Institute. The institute would not have “bricks and mortar” but would be a virtual center for providing development resources to leaders from middle management to senior officers. The institute would house all the accelerated development programs and develop additional programs, such as

- transition programs for newly promoted directors and officers

- core programs (two-to three-day workshops) on key leadership and business topics that would be aligned with both the competencies expected of leaders and the direction of the business

- an Online Development Resource Center containing development-and career-related resources supporting personal development that could be accessed from anywhere in the world

- leadership dialogues on timely topics through which senior leaders could meet face to face with employees, and often with external thought leaders, to discuss key topics relevant to the business.

Figure 4-4 shows the scope of the resources contained within the Leadership Institute, which change frequently in response to business needs.

The institute launched a new initiative in 2006, the McDonald’s Global Leadership Development Program (GLDP), that focused on accelerating the development of some of the highest-potential officers. The program was completely funded from the CEO’s budget, which sent a loud message regarding Jim Skinner’s support for leadership development. The GLDP was a truly global effort built using a combination of internal expertise and external thought leaders. The GLDP faculty comprised a combination of external speakers/facilitators and senior leaders. Several members of the McDonald’s Board of Directors also participated.

The program design focused on

- knowing the market and the customer

- executing to deliver results

- leading innovation

Figure 4-4. Scope of Resources for the McDonald’s Leadership Institute

- paying attention to ethics and values

- enhancing self-awareness and driving for continuous personal development.

The initial 20 program participants came from all over the world to attend the three-week course (made up of three one-week sessions spread over five months in both U.S. and non-U.S. locations). There was a great deal of “stretch” built into the program that forced participants to think beyond McDonald’s in a broader, more strategic way than they were accustomed to doing. Several members of the 2006 class have been promoted as of this date. The GLDP’s second course of study took place in 2008, and plans are for the program to run every other year to to ensure that its high standards are maintained.

The McDonald’s Leadership Institute continues to grow, and its brand has become increasingly prominent within the company. The institute and HU have a strong partnership and are collaborating on several major initiatives to ensure that their focus and curriculum are totally aligned from crew training through officer development. The vision and end goal is for every McDonald’s employee to understand the leadership and technical requirements for every role at every organizational level and to know how to access the development support needed to meet these requirements. Though there is still a great deal to be accomplished, significant progress has been made, and there is a strong commitment to “stay the course” until the vision has been achieved.

The Impact of Talent Management Initiatives

It is clear that talent management initiatives have made a significant contribution to McDonald’s, thanks to the efforts of many. There is now a strong discipline for talent management processes, and solid metrics to measure success are being tracked on a yearly basis. Let’s look at three of these metrics. The first metric is the strength and diversity of the current leadership team, which includes

- the annual performance rating distribution

- the percentage of leaders assessed as having advancement potential

- the percentage of lower performers on improvement plans (“improve or remove”)

- year-over-year changes in diversity.

The second metric is the depth and diversity of feeder pools, which includes

- the percentage of key leadership positions for which there are at least two backups identified (year-over-year improvement)

- the diversity of feeder pool candidates.

The third metric is the retention of top performers and those with high potential, which includes the percentage of those rated exceptional (top 20 percent) and leaders with advancement potential who are retained each year.

Progress has been made on all these metrics, and, for most, we are at levels of performance that are within our target levels. (For confidentiality reasons, the data on actual results cannot be shared.)

The commitment level of our CEO and our senior leadership team has been strong and has been sustained for several years. Senior leaders are modeling behaviors that demonstrate their commitment to talent management and leadership development. CEO Jim Skinner credits the focus on talent management and leadership development as one of the, if not the most, important factors accounting for the company’s financial and market performance.

McDonald’s has been receiving much recognition for its talent management efforts in the external community. In 2006, it was ranked by Fortune magazine and Hewitt Associates as one of the top companies for leaders. In 2009, it was also recognized as a top company for leaders by Chief Executive Magazine and Hay Associates. Overall, though McDonald’s is extremely pleased with the progress it has made in the talent management arena, it is also recognizes that there is much more to do. Three areas where progress needs to be made are

- forging a stronger linkage between talent planning and strategic planning—this is occurring, but the rate needs to increase

- making better use of planned job moves to accelerate development—finding creative ways of overcoming the barriers imposed by mobility restrictions and work/life balance issues

- improving overall execution.

Conclusion

McDonald’s has taken a carefully planned approach to building its talent management and leadership development capabilities since 2001. It started by fixing its performance management system, the foundation for any and all talent management initiatives. It progressed steadily and was bolstered by strong support from its senior leadership team. Some of this support was generated or “awakened” by the untimely and tragic deaths of two CEOs in little more than a year, which made talent management and succession painfully real for McDonald’s—and they have been real ever since. The metrics that have been tracked over the last several years attest to the fact that there is now a strong leadership team in place at McDonald’s and a strong pipeline of internal leadership talent ready to replace them. The performance of the business reflects this strength.