Chapter 6

The Joyful Work of Building Imaginative Capacities Matters: Know that Learning Predates School

To the Reader: Twilight

By Chase Twichell

Whenever I look

out at the snowy

mountains at this hour

and speak directly

into the ear of the sky,

it's you I'm thinking of.

You're like the spirits

the children invent

to inhabit the stuffed horse

and the doll.

I don't know who hears me.

I don't know who speaks

when the horse speaks.

Credit: Chase Twichell, “To the Reader: Twilight” from Horses Where the Answers Should Have Been: New and Selected Poems. Copyright © 1998 by Chase Twichell. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Copper Canyon Press, coppercanyonpress.org.

One of the many magical parts of traversing the city via subway is the MTA's (Metropolitan Transit Authority) Poetry in Motion. Yes, it's true. Poems adorn the 150‐year‐old+ vessels of this grand city. The poems are situated in colorful, nuanced prints that absolutely pop out of the yellow‐beige‐orange‐murky hues of the D/N/R train walls and its seats. The lyrical force of these poems stands strong, holding the beauty of the ride steadfast. The poems share that matched fortitude with their parents: ride any train in the city and you'll be embraced, lifted, and/or challenged by lines from the likes of Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton, Marilyn Nelson, and Billy Collins.

The train ride offers a space for deep reflection for those who ride it, and after a full day of teaching, I remember a poem on a subway ride that provided deep clarification to a notion that sat in my heart, undefined, but certainly a driver to my teaching. Chase Twichell's poem “To the Reader: Twilight” popped out from the walls and lifted me. I was riding the D/N/R train from 59th Street and 4th Avenue to 4th Avenue and 9th Street from the elementary school I taught at in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, to my then‐home in Park Slope, Brooklyn; neighborhoods touching, but not close enough for a quick walk. “To the Reader: Twilight” massaged my heart with an affirmation, a knowing, that until that point I hadn't yet been able to put into words:

You're like the spirits

the children invent

to inhabit the stuffed horse

and the doll.

“The spirits the children invent to inhabit the stuffed horse and the doll” was, is, probably always will be the thing I seek to protect, to nurture, to grow, name and acknowledge within all the spaces I share with children. There's nothing quite like the life a child gives to a toy, or an invented land erected from scraps of recyclables. Whether I am at home, in the classroom, or spending time with friends, I take the opportunity to reaffirm the majestic mind of children by witnessing their questions, saying “yes” to their strange materials requests, or encouraging a divergent thought.

My will for encouraging imagination within kids and young adults is so strong because I know those majestic minds of theirs are in constant threat of being scrubbed of inquisition in the name of high scores, “good” grades, or prescribed curriculum. The spirits the children invent names the bursting, loveful imagination that surfaces from children's minds, and the growing of these ideas and seemingly impossibilities, are sacred to our craft in teaching.

However, those lovely minds will only be fed the vivacity they deserve so long as they are not diminished by the institutions and systems and traumas that surround them. We must do everything in our power to protect, honor, and cherish those spirits of children Twichell names in the learning spaces we create for our students.

Here's my reflection.

Warrensburg Middle School, Sixth Grade: 1994

It's 1994, and it's the era of talk show drama and MTV. Angie, Kayla, and I were watching three or four talk shows a week, serving ourselves a healthy dose of Ricki Lake, Maury Povich (if our parents weren't home), and sometimes Oprah. During this slumber party, we lip‐synced to Ace of Base, Boys II Men, and The Cranberries; we drank copious amounts of hot chocolate; and we reinvented the talk‐show circuit. Reimagining ourselves as talk show queens, we did our best impressions of the dramatic, confusing, and insatiable guests the hosts would interview.

It's hard for me to remember the made‐up drama, but I do remember when it was my turn to play talk show queen, I chose Ricki Lake. I tolerated absolutely zero nonsense from the guests (Vanilla Ice and Tonya Harding) my friends role‐played. Instead, I served up question after question to the ill‐conceived drama these pretend guests portrayed before eventually posing a multitude of opinions followed with a quasi‐solution. My fervent interview style swayed my friends, and they suggested I consider a career with MTV rather that pursue a college track.

While I clearly never landed a role on the cast of Road Rules or The Real World, I'm grateful for their feedback. I remember feeling my inner life warming through this sort of incremental surfacing of who I could be. In school, the opportunity to assert opinions on pop culture or the merit of celebrity behavior that we young people were so curious about was rare. More often, we were shushed away or had the TV remote “offed” when talk of O.J. Simpson's case was broadcast or when we wondered out loud about Bosnia.

At home, sometimes I had chances to exercise my stance on how things should be, but my parents were working a lot. Making space for me to explain the zeal behind Tonya Harding's attack on Nancy Kerrigan wasn't a priority. My parents listened to me, and my friends entertained my spirit within the safe space of slumber parties, but more often than not, I exercised my assertions in the safety of my bedroom.

It's a wonder that the spirit of the talk show version of myself, the one who solves problems, provokes the idea of “should,” and articulates how things could go survived. From what I remember, versions of that self primarily showed up at slumber parties and moments in class where I had completed my work, stared out the window, and replayed scenarios of tackling topics within my imagination.

Upon reflection, I can't help but notice how I had embarked upon the implicit project of separating my inner life and outer world assigned to me by one of the environments I most consistently interacted with: school.

Question mark.

“Do Schools Kill Creativity?”

Humans are born curious: inquiry is our birthright. The spirit of imagination is intrinsically developed in our most early years of life through our biology, our curiosity, and our interaction with the environments and people that surround us. It is one of the most special components of humanity, a sacred part of who we are, it is what makes us us.

But perhaps one of the greatest tricks Western civilization has played upon itself is that school is the absolute primer for a person's most powerful learning. While school and classrooms and teachers offer great potentiality and momentous learning for students within their spaces, if we are to capture and nurture imagination, it is important for us to understand it from where it starts, from the very beginning.

There is a growing body of research that shows how schooling has actually impeded students' curiosity and creativity. The late educationalist Sir Ken Robinson brought this conversation to dinner tables around the world with his TED Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” (Robinson 2006). With 73.5 million views to date, it is the most watched TED Talk of all time. In his talk, he argues two major points regarding the relationship between schools and creativity. First, Robinson says, “We don't grow into creativity, we grow out of it. Or rather we get educated out of it.” Second, he says, “Creativity is as important as literacy and we should afford it the same status.”

Robinson builds on these points in his later TED Talk entitled “Changing Education Paradigms” (2010), further illustrating schools and the barriers they impose on kids' curiosity. This time, he cites research from more than a decade prior to his first talk, illuminating divergent thinking present in early childhood that dissipates in later schooling by using Land and Jarman's Breakpoint and Beyond research (1992). This longitudinal study demonstrates the inverse relationship between years spent in schooling and creativity. Land and Jarman worked with 1,500 kindergartners with the goal of measuring creativity after every five years spent in school. In the test, students were given a paper clip and asked “What are all the ways you could use a paperclip?” At age five, 98% of those students received a creativity score on a genius level. At the age of 10, 30% of students received a creativity score on a genius level. At age 15, the number of genius‐level creativity scores reduced to 12%, and at the average age of 31, scores reduced to just 2% (Land and Jarman 1992, in Robinson 2010).

There are a number of variables at play in regard to factors impacting the ability to summon creativity throughout school, especially when culture, identity, place, curriculum, and teacher agency are taken into account. I also have questions regarding environmental factors around the distribution of the creativity assessment (How long did students have to take the test? At what time of day did they take it? Who was their proctor?) as well as the assessment itself. However, there is something to be said about the massive and steady decline in scores demonstrated by over thousands of people as they spent more time in school.

So, what does the inverse relationship between students' creativity and time spent in school mean for educators? First, it's important to note that teachers and students have a similar relationship between practical, creative thinking and schooling: The more years we spend within the realm of institutional thinking, the less our sense of self and our imagination is revealed within our pedagogy. In this book, we have worked on a treatment plan to remedy “going through the motions” of school life, regaining our sense of self by digging into our past and our present. We've worked to expand our imagination toward dreaming up future goodness, and the mechanism we use to initiate that process is by both reestablishing and reimagining our pedagogy.

Creativity, Curiosity, and Childhood Development

Creativity underscores all of that work. It is an innate human process; it is how we make new ideas and fashion our thinking, our experiences, and even the materials we use in ways that are most authentic to our unique communities. Creativity is an aspect of our joy, without it, how are we equipped to work toward justice?

On the journey to licensure, teachers experience a course in childhood development to varying degrees. However, it's often before in‐service teaching starts, and it's a body of knowledge that sits on the backburner for many people working in upper elementary or secondary schools. In other words, it's been separated from school‐based decision‐making. More and more often, we see the life of child development disappearing from curricular landscapes for even our youngest children. It makes me shudder.

It doesn't have to be this way: together, we can imbue childhood life back into school!

First, let's consider all kinds of ways and all kinds of things children learn from birth to the time they turn four years old. Each time I delve into the scores of work and research documenting the intellectual life of very young children, I am blown away at how capable they are, by how much they know and are able to do before they even arrive to school.

I didn't start my career in education knowing much about childhood development. Aside from the experiences I had caring for my nieces and nephew, who were school‐aged during my first year in grad school, I'd not spent significant amounts of time with people four years old or younger. In fact, I taught for five years before I spent significant amounts of time with very young people, before I began to deeply explore how synapses and neural pathways and environments and caregivers coalesce with one another to inform what a child knows.

Before I considered how much adverse childhood experiences have power to shape and undo important milestones in life, or before I knew how all the funds of knowledge kids were bringing into school could be embraced and built upon, rather than straightened out and stretched toward assimilation, I was well underway teaching students in high school.

I was mothering my two very young children at the same time I began teaching fourth and fifth graders within an elementary school. They, of course, were my ultimate teachers, and it was from them that I learned much of what I now know about childhood development. In addition to my elementary school‐aged teachers, I've also learned, and continue to learn, by witnessing my own children's development, reading well‐known research from Jean Piaget, Marie Clay, George Land, and Beth Jarman, and reading and listening to lesser‐known (but equally important) work from the advice of bloggers like Janet Lansbury and Dr. Sears, as well as all of my family members. Really, the sources I learn from are endless!

Here, I give you the CliffNotes version on all the things kids learn before they even receive any schooling, from the very beginning. Later, we're going to expand and bridge this information into the kinds of decisions we make at school to sustain deep levels of curiosity for the students we teach, allowing their inner lives to fuse with the outward experience of school.

Powerful and peer reviewed, The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University provides succinct research for understanding “the science” behind childhood development. It's an excellent source for foundational knowledge for how humans learn and all the different ways their environment and early experiences impact the ways in which they engage with their peers, families, and school. The Center on the Developing Child's website is fueled with multimedia for taking a deep dive on the topic. In short, here are salient points regarding childhood development and learning:

- In the first few years of life, over 1 million neural connections are formed every second. Already, as babies, humans are exercising powerful cognition! The brains of babies are strong, and with each day, they grow more complex. The very young brain is constantly revising itself, adding more details to its once simple structure. Sensory pathways for things like hearing and vision are developed first, followed by early language development, and later higher cognitive functions like using a spoon to eat with or learning to walk.

- The strength of cognitive development is incumbent upon the richness of babies' interactions with the humans and environment that surround them. Genes and experience are both at play, and the idea of “rich environments”1 is one that must be complicated … we don't want to adopt assimilationist perspectives! Perhaps you've heard of “serve and return”? Serve and return is the idea that if a baby makes some kind of baby‐contribution to the world, like smiling, babbling, or taking a step, the baby's actions are affirmed by another human, ideally a caregiver, with some type of communicative warmth, for example, a returned smile, an affirmative sentence in response to the baby babble, or congratulatory steps after the walk. If the baby serves, or “contributes” to the world, and is not acknowledged for their effort, the brain's structure develops more weakly, causing gaps in learning and activating early stress responses.

- In the earliest stages of life, brains are most elastic, accepting, adapting, and revising all kinds of information. This is one of the many reasons young children are able to capture and become fluent in more than one language much more easily than adults. Humans are never too old to learn new things, change their habits, or strengthen neural pathways, but as kids and adults grow older, new habits are harder to develop because the brain is less elastic.

- The brain does not work in compartments! All of its parts—social, emotional, and cognitive capacities—are in constant interaction with one another. This is why it's so important to make space for children to explore a full range of emotions in all the spaces they occupy. When we ask them to push their feelings aside, essentially we are asking them to use a small piece of their mind.

So, at the tender age of two, very young children have developed a brain with millions of neural connections, they've used their brains to revise and select and grow new ideas about the world, and, for many, they've built a solid foundation for language learning they'll use throughout their lives. It's no wonder they are so temperamental! They've done an incredible amount of work to simply be.

Working Toward Justice: The Continued Conversation on Student Centeredness

People talk a lot about student‐centeredness. It's a stance that many educators, including myself, have declared over and over again throughout time and throughout many different places. It is what my partner, Cornelius, has named “radically pro‐kid.” But it's more than a proclamation. It's also a deep study on learning, on development, on curriculum‐making, and knowledge‐growing. We've talked about some of those things already, but in reality, working toward student‐centeredness, or thinking about what it means to be “radically pro‐kid” is a never‐ending conversation that evolves as kids grow older, or new kids enter your learning space.

You may be wondering, Why call it radically pro‐kid as opposed to student‐centeredness? In truth, I wish it wasn't such a radical thing to center children and adolescents in the work of teaching and learning. However, as we've explored the scope of kids and school since its inception, there hasn't been a moment in time where children have truly been at the center. Since Thomas Jefferson's original “Bill for the General Diffusion of Knowledge,” along with other white, male intellectuals and politicians like Noah Webster, John Dewey, and Horace Mann, each iteration of schooling has been in the name of democracy and citizenship, but according to each of their preferred social orders (Ravitch and Vitteriti 2001, p. 9). Their ideals of citizenship scarcely include children outside their own white, English‐speaking, able‐bodied, and male identity markers. White, able‐bodied, English‐speaking girls worked until 1972 to be afforded the same rights as their male counterparts.

Arguably, even those children who were considered within the educational paradigm of Jefferson, Dewey, Webster, and Mann were still subjected to the idea that being a good citizen meant being productive, and that to be productive meant high achievement in schools. High achievement is a component of schooling that has been omnipresent in the conversation regarding “What makes a good school?” However, for me, the more important question is, “What makes a child sustain their joy and curiosity?” I argue that when you hold that question tight, when you assert that question alongside achievement‐oriented policies, that is when you are being student‐centered. Because you will almost always be doing this in tandem with policies that have eroded joy and contained divergent thinking, the radical element of this work has surfaced, hence Cornelius's nomenclature: to be student‐centered is to be radically pro‐kid. Therein lies another relationship between justice and joy, and how we work to spread it in our schools.

Immersing Oneself in a Student‐Centered Space

When I work to build student‐centered experiences in a standards‐based classroom, I do so by spending a lot of time in educator spaces. I keep my eyes and ears open in school communities, and pay attention to the felt knowledge I experience by watching how kids relate to, communicate with, or even physically locate themselves to teachers within communities who do the work of positioning children as the center of their pedagogy in ways that are clear and subtle, and are especially evident in the ways children react and respond in the classroom communities they have designed. Keep in mind—I'm in educator spaces in a lot of ways. Yes, I'm a coach, but I'm also a teacher volunteer at a local summer camp, and I also am the parent of two elementary‐aged children. There are numerous spaces where I am watching, observing, analyzing, and sense‐making the multitude of human interactions on a daily basis.

One of the most meaningful and salient observations is the way in which my youngest daughter's pre‐K teacher positioned students at the center of her pedagogy. Markedly, she did so through an undercurrent of love. I wrote about this phenomenon a while ago, for no other reason than that I didn't want to forget it. I knew from the research that this pre‐K year would probably be the most joyful year of her life spent in school. Below, I describe this felt experience and analysis in detail.

2018

My Daughter's Pre‐K Classroom, Brooklyn, New York

Every time I walk into my youngest daughter's pre‐K classroom, my heart swells. At the top of the stairs leading to her classroom, we are first greeted with a carefully constructed and kid‐created three‐dimensional alphabet museum hanging on the wall, on which most days we pause to find the letter “N,” which is how her classroom door is labeled: “Classroom N.” The walls are peppered with the work of inquisitive young minds; recently, stories of the children's families, drawn exclusively by the children, were posted alongside collages they had made earlier, including pictures of people in their lives who were important to them, with other fuzzy and shiny objects decorating the images.

Upon entering her classroom, we go through a fairly typical routine of unpacking, washing hands, and flipping her picture over on a chart to show everyone she has arrived (all the children do this). Also, similarly to many pre‐K classrooms across the country, the classroom has several “areas” that children are allowed to spend time at each morning with one another, including an ever‐changing Dramatic Play corner (since the beginning of the school year, it has shifted from a kitchen, to a doctor's office, and most recently—a gym (with a pretend treadmill crafted out of a yoga mat and cardboard!!!).

However, not so typically, on a wall near the class's daily schedule there is a “feelings wheel,” where children place an arrow alongside the feeling they are currently experiencing. They can choose to talk more about it, or not. Additionally, every Tuesday, they have what is called Friends School, where the school social worker pushes into the class and works quite explicitly on a curriculum that helps the children develop strong social and emotional skills. There is a biweekly parent/caregiver group that coincides with the same curriculum, led by the same social worker, supporting families to build those same skills with their children. Cornelius and I receive a flier in Indi's backpack every week, highlighting the activities Friends School engaged in with tips for us on how to support our child at home.

After about a month of pre‐K, Indi said, “Mama, do you wanna know something?” I said, “YES!” (I usually respond pretty enthusiastically when any kid, especially my own, is on the cusp of articulating an idea that has been percolating.) “My teacher loves me,” she replied, in the same tone someone would tell you a benign fact, like “The sky is blue.” It was clear that in her mind there was no doubt that she was loved at her school, within her classroom, between the adults who care for her every day when her family is not with her. I asked her how she knew, and she said, “Because Ms. H told me.” So, quite literally (and also implicitly through a million other kind and gentle micro‐interactions taking place between teachers and children), my child is loved in school. Just as the sky is blue, it is a fact.

The comment, “My teacher loves me,” was arresting, and it occurred to me that I, too, experienced a similar feeling whenever I dropped her off or picked her up at school: an undercurrent of love. A bit of salve for my fiery heart working in a big giant school system, where sometimes the softness of working with children gets lost in the harshness of a system that doesn't protect grown‐ups' well‐being, that maybe centers itself too much on achievement and not enough on growth and progress. This undercurrent of love so clearly carries a community of children forward because, more than anything, it centers their development and well‐being as the priority of their school experience.

Those notes, put together as an imprint for my work and to capture a beautiful year in school for my daughter to look back on, beckon happy tears: there is nothing like dropping off your child in a healthy school space where they declare evidence‐based love for and from their teachers. I'm also slightly heartbroken after taking that trip down memory lane because it was pre‐COVID schooling, which was not perfect, but certainly more resourced. And I'm also a little rejuvenated—we've so much to learn from the ways of pre‐K!

A few years back, I worked briefly with a pre‐K center on a topic‐based professional development on Universal Design for Learning. When I prepared for the work, I studied the New York State Prekindergarten Foundation for the Common Core standards that the New York State Board of Regents adopted in January 2011. The New York State Prekindergarten Foundation for the Common Core is divided into several domains, with the first domain called Approaches to Learning. Below, find a summarized version of the foundational skills included in this domain:

As I read and reread the text, never before had I seen such appropriate guidance for learning; guidance that could really work for any child within almost any curriculum. Those skills are just a small taste of the guide in its entirety, with other domains including: Physical Development and Health, Social and Emotional Development and Communication, and Language and Literacy. There is a Part B in the document as well, including English Language Arts and Mathematics standards from the Common Core State Standards.

Comparatively, when children start kindergarten within the many states that have adopted Common Core Standards or states that have adopted their own standards in recent years, there are no standards named “foundational,” rather, they are divided into Reading, Writing, Language, Speaking and Listening, and Mathematics, where children are expected to do things like:

CCSS.ELA‐LITERACY.SL.K.1

Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about kindergarten topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups. (Common Core State Standards Initiative)

And:

Use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose informative/explanatory texts in which they name what they are writing about and supply some information about the topic. (Common Core State Standards Initiative)

Many children will be able to work toward those standards and participate in peer collaboration and writing with zeal. They will come to school excited, and rush to their caregivers to tell them about all the wonderful things that happened in their kindergarten class that day. Conversely, many children will experience great difficulty sitting in their chairs on the rug for many minutes, taking turns during conversations and/or during choice time, or even spending six hours of classroom time without having a tantrum, and their caregivers might unpack a note from their teacher in their backpacks requesting a meeting, or a paper that includes how many smileys they earned for the day.

It is with deep realism that many children entering kindergarten are still developing their “approaches to learning,” regulating their emotions, and developing positive relationships with those who surround them. Even more importantly, and of deeper concern, is that many students entering middle school, high school, and even college are still grappling with those same issues. Yet—the crux of their development seems to have been left out of the core of their school experience, leading to just that—an experience where they go to school, as opposed to a place they go to learn.

Placing Kids' Developmental Needs at the Center of Learning in Community

When we think about creating spaces of learning with schools (and I know, it's funny how deliberately we must invest in making a school a learning space), it makes sense to start at the very beginning of a child's experience with school. When children's emotional development and social skills are supported as the impetus for learning throughout the day, really, the fiber that makes the fabric of the classroom community, they feel better and their hearts and minds grow more. When kids feel better, teachers feel better.

In collaboration with teachers, I worked hard to think about what it means to develop the way children approach not just learning, but how to learn with one another. Moreover, we wanted to integrate the work of supporting children developmentally throughout the day, not just tucking the work in on the fringes of the day into a “character education” or “mindfulness” period. We'll start with a bird's‐eye view in a kindergarten classroom, taught by Rachel Sharpstein, and then zoom in, noting how this teacher's work took place over time, with perseverance, and with great care.

When I met Rachel Sharpstein, I had been working as a staff developer for the Teachers College Inclusive Classrooms Project in her school for a few months, working to build inclusive practices with several teacher teams in ICT classrooms.2 During a debrief with the school's principal, it was requested that I support one of their kindergarten teachers working in a general education classroom, mostly teaching by herself, who was feeling overwhelmed and particularly challenged by a few children, and very challenged by the whole class's general dependence on her for everything. The principal suggested I might help create classroom stations, or centers, with her to decrease the amount of whole‐group learning.

As an educator who seldom taught alone, I knew I had to enter this space with great empathy: a 27:1 kid:teacher ratio is rarely easy. I first had an opportunity to visit her classroom. Before I meet with teachers, I usually request a low‐stakes classroom visit to get a sense of their community vibe, to witness and collect important micro‐interactions and other subtleties taking place between kids and kids and teachers and kids, and, also, to note how the room set up affects communication. Then, I engaged with her one‐to‐one, channeling all my active listening skills.

I firmly believe in teacher agency, and one way we can work together to reaffirm teacher agency is to invite teachers to our platforms and include them when we talk about different ways to enact justice and joy in our classrooms. To that end, I invited Rachel to be included in this text. Below, you ‘ll find her voice sharing the journey we embarked upon, underscoring the choices we made to improve both her and her students' experience.

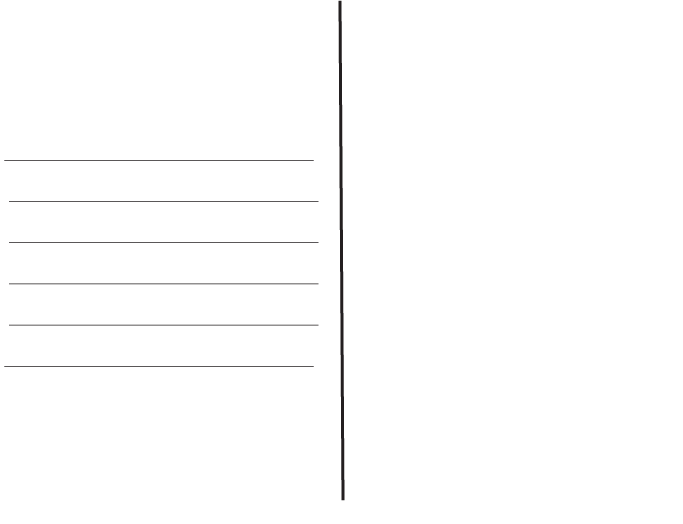

In Figure 6.1, find the materials Rachel and I developed as the Super Solvers became ritualized in Rachel's classroom community.

I want to note: Rachel and I didn't create Super Solvers out of thin air. As we brainstormed and planned together, we also read and researched together. The following articles and texts informed the learning designs we created.

- What Is Shared Imagination & Why Is It So Important to Relationship Development? by Michelle Garcia Winner, MA, CCC‐SLP and Pamela Crooke, PhD, CCC‐SLP from socialthinking.com.

- “The Importance of Educational Partnerships,” Chapter 1 in the book Educational Partnerships: Connecting Schools, Families, and the Community by Amy Cox‐Petersen.

- Whole Body Listening by Susanne Poulette Truesdale.

- Buddy System Tip Sheet: Teaching Tools for Young Children by R. Lentini, B.J. Vaughn, and L. Fox.

We took my field notes from Rachel's classroom that included interviews with students, analysis of student artifacts, and observations of times where children demonstrated high dependency on their teacher, in combination with Rachel's direct experiences and knowledge with the kids, very seriously. Based on new understandings from our research, we named the following skills to serve as the foundation for the teams of Super Solvers.

FIGURE 6.1 Super solvers poster.

Underlying Skills for Super Solvers:

- Expressive language.

- Identify feeling.

- Express feelings appropriately.

- Express needs.

- Identify and apply resources/strategies.

- Efficiency in completing daily routines.

- Compassion.

- Empathy.

- Perspective taking.

Guidelines for Super Solver Student Pairings

From there, we developed guidelines for how partnerships would be developed. This was an important aspect in the development of the learning design. Kids showed they had a really hard time working together, so we wanted to be intentional in how the kids would be partnered. We wanted Super Solvers to be sustainable.

Ritualizing Super Solvers

After we figured out partnerships, Rachel worked to create a schedule where Super Solvers was consistent within everyday classroom life … not just something that popped up every now and then (Figure 6.2). It became a ritual, and students learned to authentically check‐in with one another after lots of practice and explicit teaching.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

| Partnerships | Morning Check In: “How are you feeling this morning? Why?” Positive Thought/Wish: (In mindful position with lights off and closed eyes) Send your Super Solver a positive wish or thought from your heart to theirs. Afternoon Check In: “How are you feeling this afternoon? Why?” | Morning Check In: “How are you feeling this morning? Why?” Afternoon Check In: “How are you feeling this afternoon? Why?” | Morning Check In: “How are you feeling this morning? Why?” Positive Thought/Wish: (In mindful position with lights off and closed eyes) Send your Super Solver a positive wish or thought from your heart to theirs. Afternoon Check In: “How are you feeling this afternoon? Why?” | Morning Check In: “How are you feeling this morning? Why?” Afternoon Check In: “How are you feeling this afternoon? Why?” | Morning Check In: “How are you feeling this morning? Why?” Afternoon Check In: “How are you feeling this afternoon? Why?” |

| Small Groups | Group Games: In groups of two partnerships, play UNO together. Talk about something that went well and something that was challenging with the whole class. | Classroom Problems and Solutions: In groups of two partnerships, give them a picture of a problem in the classroom and have them collaboratively come up with solutions. Share with the class. | |||

| Whole Class | Super Solver Solutions: Create an ongoing list for the week that the kids can add to, recognizing ways in which their Super Solvers helped them solve a problem. Post the problem and solution. Save the charts so that you can analyze the types of problems and solutions and help push them to find new solutions or best practices. | Super Solver Celebration: Write your Super Solver a thank you letter to appreciate she/he for something (specific) that she/he helped you with during the week. Share with class. |

FIGURE 6.2 Sample Super Solver schedule.

Rachel created numerous artifacts and scaffolds for students to actively participate in the various Super Solver rituals, including Thank You Cards (Figure 6.3) and Kindness Postcards (Figures 6.4 and 6.5), where students practiced recognizing each other's helpful actions and affirming each other's presence in their community.

Rachel's development of the Super Solvers rituals had a deep impact on her classroom community. Her students were becoming more independent in their learning, and were also developing supportive social skills with one another. As we continued our work together, she became more independent herself, cocreating a purposeful, deepened core of social‐emotional literacy with the children in her classroom.

FIGURE 6.3 Template used to support students in writing ‘thank yous” in Rachel's classroom community (Sharpstein 2017).

FIGURES 6.4 AND 6.5 Templates used to support students in writing affirmations to one another in Rachel's classroom community (Sharpstein 2017).

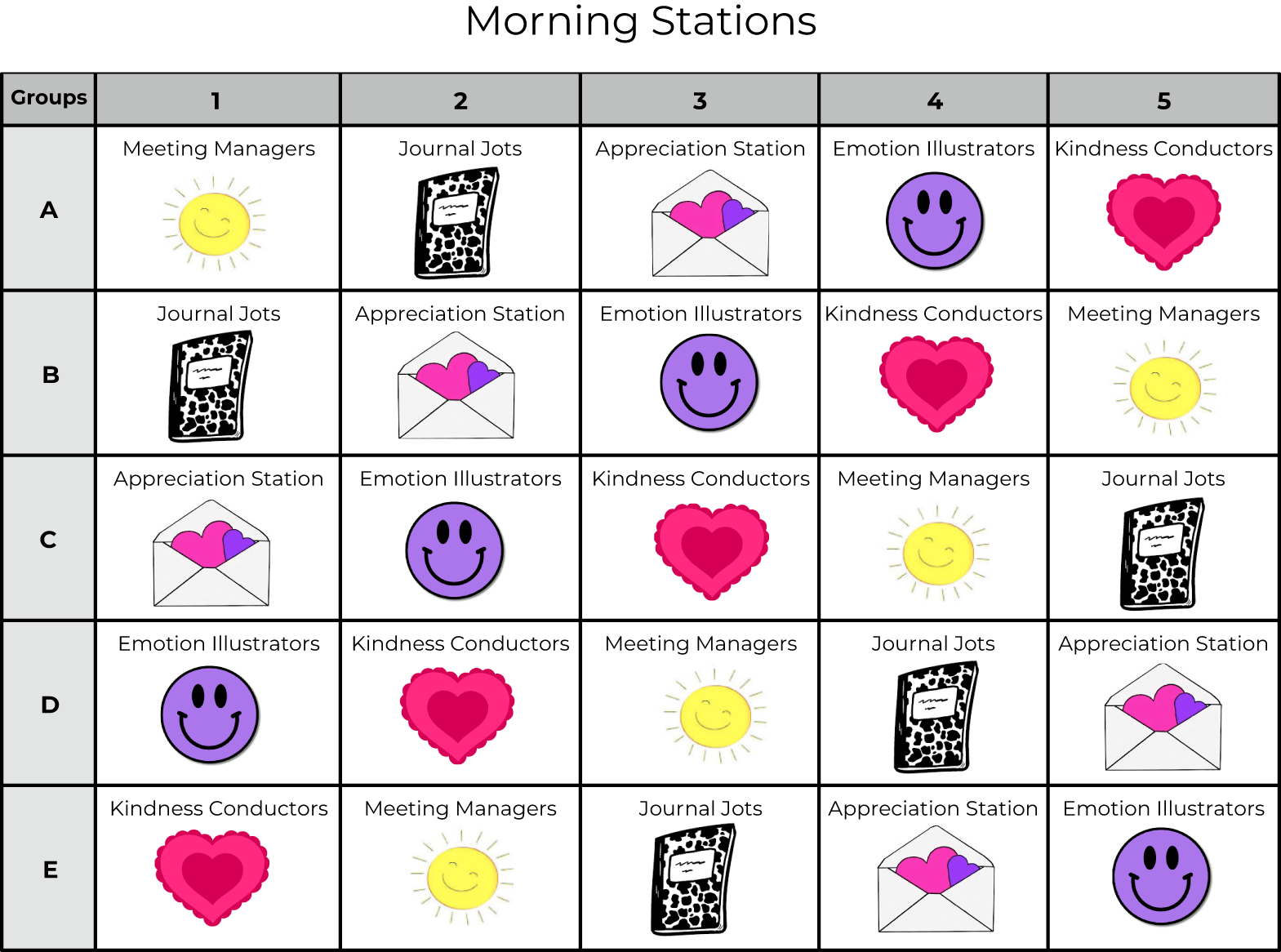

Figures 6.7 through 6.13 are artifacts created by Rachel Sharpstein that supported the students' participation in groups, working toward stronger social and emotional literacy.

FIGURE 6.7 Station schedule.

FIGURE 6.8 Journal jots sample A.

FIGURE 6.9 Journal jots sample B.

FIGURE 6.10 Kindness conductors student instructions.

FIGURE 6.11 Kindness conductors teaching chart.

FIGURE 6.12 Emotion illustrators station.

FIGURE 6.13 Appreciation station.

Rachel Sharpstein had a high degree of teacher agency, and her work was supported by school leadership that built the school from inclusive principles in education. The artifacts and learning designs shown are examples of “homegrown” curriculum discussed in the previous chapter. Rachel was able to share her learning and classroom experiences with other teachers in her school during an Ed Camp‐style, locally derived, teacher‐run professional learning day at her school.

Notes

- 1 Rich linguistic environments are complicated through Sarah Michael's commentary on Hart and Risley's seminal but contentious work, Meaningful Differences, on early language development comparisons between well‐resourced families and lower‐income families.

- 2 Integrated Co‐Teaching, as defined in the United Federation of Teachers contract: Students with disabilities who receive Integrated Co‐Teaching services are educated with age appropriate peers in the general education classroom. ICT provides access to the general education curriculum and specially designed instruction to meet students' individual needs.