Chapter 8

Negotiating the Curriculum for Your Current Students in Today's World

One way I like to begin planning for learning experiences in connection to larger ideas and goals that young people have explicitly named, situations that have come up, or even the news is to use Vivian Maria Vasquez's concept of “negotiated curriculum” (2004). According to Vasquez, the negotiated curriculum is a “process for adjusting and reconstructing what we know, naming what matters for us, situating learning in lived experiences in connection to grade level standards” (p. 1). Note this is a stark contrast to designing curriculum for kids to accumulate information and skills in isolation from their lived experience and the communities that surround them.

TABLE 8.1 Template for making curriculum relevant through negotiation.

| Curricular Standards | Revised Curriculum |

|---|---|

| (Reading) Ask and answer questions about key details in a text read‐aloud or information presented orally or through other media. | |

| (Writing) Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well‐chosen details, and well‐structured event sequences. | |

| (Social Studies) Recognize, analyze, and use different forms of evidence used to make meaning in Social Studies (including primary and secondary sources such as art and photographs, artifacts, oral histories, maps, and graphs). | |

| (Math) Understand the relationship between numbers and quantities; connect counting to cardinality. |

Loosely adapted from Vivian Maria Vasquez, Negotiating Critical Literacies with Young Children (2004).

I use a template like the one in Table 8.1 that has been adapted from Vasquez's work on the negotiated curriculum to organize my thinking in terms of what standards I am obligated to teach according to my contract, and spaces for connections and experiences that are relevant to kids that speak to the skills, content, and habits that are embedded within those standards.

In Table 8.1, the standards included on the left are Common Core State Standards. Again, as we are naming essential questions or the big ideas that inform our route, these ideas must be connected to grade‐level standards. On the right, there is space to consider what revisions are necessary to both accommodate kids' academic needs as well as the changing tides of today's world.

To negotiate the curriculum is to create relevant learning experiences that directly speak to the needs of the students you teach. That is, it is working to promote justice in their learning and everyday being, even as they are 7‐ or 10‐ or 13‐year‐olds. Table 8.2 is more expansive than Table 8.1, and helps create space for the negotiated pieces, or the adjustments you make to learning experiences that may have already been written, or that you have planned quite differently in years past.

After brainstorming a negotiated curriculum that is connected to learning mandates, or state standards, the next step is to organize learning activities across a unit into different “bends.” If the learning design is your roadmap, the curriculum is the itinerary for the journey you embark on, and all the activities embedded within that curriculum are the different places you stop and things you experience. Eating a three‐course dinner after one hour of driving wouldn't make sense, just as starting a dynamic group project on day one of the unit wouldn't make sense either. As you pace the different activities with various lesson plans across the unit, imagine the first leg of the journey, the second leg of the journey, and the third leg of your journey. What learning activities make the most sense for your students to engage in earlier? Later? What skills are you teaching along the way in addition to the content? Do your students have the necessary habits to engage in the activities you've created? What habits will you need to teach?

TABLE 8.2 Planning for your current students in today's world.

| Issue(s) and Data | Community Happenings/Situational Context | Areas of Study, Including Texts, Materials, and Other Resources | Actions, Experiences, and Projects | Connected Topics and Further Areas to Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School closure, COVID‐19 global pandemic, social gaps between kids Kids' comments:

| After a series of varied messages from the school district regarding COVID‐19 school closures, students were no longer able to see each other regularly at school. Teachers across the city were told to not address COVID‐19 directly, and many students in the lower grades overheard from older kids at the school that the “germs had come from China.” One child overheard another child say that if they ate Chinese food, they would get COVID. When school buildings officially closed, and all students learned remotely, first graders said they didn't like playing with only one friend. They said they liked playing with “many friends.” Currently, there is a social gap with many kids who continued to attend hybrid learning, vs. kids who were fully remote last year. |

|

|

|

Loosely adapted from Vivian Maria Vasquez, Negotiating Critical Literacies with Young Children (2004).

Unit plans take many shapes and forms, just as lesson plans do. I have lots of curricular maps and lesson plan templates I've used in the past, but, honestly, no template has made an enormous difference in my own work as a classroom teacher, or the many teachers I have partnered with. Rather, it is the style of thinking of UbD, and the adoption of a culturally relevant and sustaining framework as an operational lens, that has made all the difference (combined with teacher agency and human development, of course!). That said, I invite you to use whatever curricular planning tools and templates feel best for you in the name of designing justice‐oriented learning experiences!

There is a common misconception that when you're negotiating or revising a curriculum with the children you teach, you're walking away from standards‐based teaching, or they are missing something vitally important within a curriculum as it was previously written. This is simply untrue. By naming the skills, content, and habits embedded within the standards we are obligated to teach in connection to the questions, ideas, and wonderings students surface in school spaces, we are simply moving through an operational stance of how learning works. Additionally, when we consider the unique human experiences of individual children, and the cultural backgrounds they present within our communities, we are enhancing the learning landscape by building a pathway for strengthened relationships and a more open community of learners.

In the following sidebar are artifacts from students in New York City schools that demonstrate this sort of literacy learning.

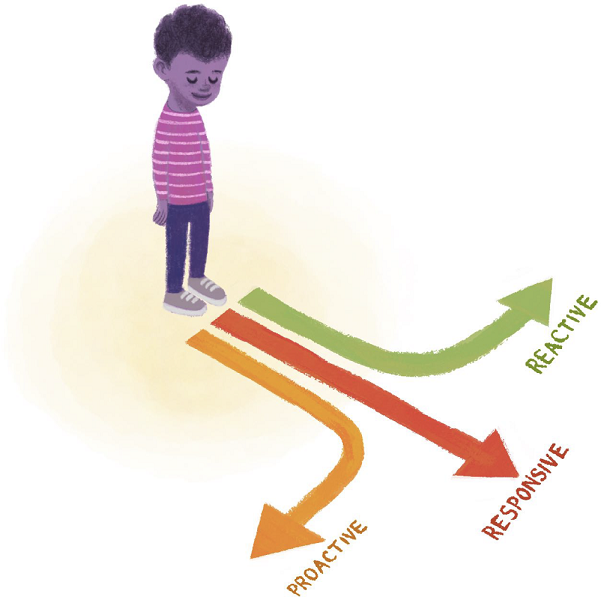

Three Paths for Considering Kids, Justice, and Curriculum Design

Three paths for considering justice‐oriented learning designs.

We are now at the point in our curriculum‐making where we have decided where we want to go, that is, we've documented our big questions, we have engaged in a variety of assessments, and we’ve collected information about our students to understand their personalities, learning needs, and cultural backgrounds more robustly. In stage three of Wiggins and McTigues's UbD, this is where learning experiences are planned. Some people like to think of this part as “lesson planning.” And while that is true, sometimes a lesson plan template can get in the way of creative possibilities. In the end, I almost always will document a period of learning within a lesson plan format. However, before I do that, there's a bit more artistry and strategic thinking involved.

In terms of strategic thinking, the ways educators approach justice‐oriented learning designs typically go one of three ways. First, and most formidable, is the proactive approach. This is when educators deeply understand childhood development, they've studied up and listened and learned about their students' families, cultural backgrounds, and learning needs, they are paying attention to what's happening in all the in‐between spaces of school like the hallways and cafeteria, and it is from those areas that inform how their classroom community is built and how their curriculum goes. One of the most devastating factors during the height of the COVID‐19 pandemic in schools was the inability of educators to do any significant levels of proactive planning; every moment of school changed so drastically on a daily basis, and educators were often forced to make reactive decisions.

Educators also approach justice‐oriented learning responsively. This is usually the best‐case scenario given the resources educators have and circumstances that most educators are situated within. This is when educators witness, observe, listen, and do all the things they would have proactively, but in the case of the responsive teacher, it's not always possible to anticipate what students need or what is going to happen. Rather, they actively listen to students' needs and either respond in the moment or design learning in the coming days to address those needs.

The third strategy, the reactive approach, is also very common. While this approach is better than not doing anything at all in the pursuit toward justice, it often comes too late, after people in the community, usually young people, have already been harmed. For example, after a series of racial epithets were drawn on bathroom stalls, teachers might begin to design learning experiences that address racial acceptance.

These approaches correspond with different ways of designing justice‐oriented learning, which you will find in Table 8.3.

In this section, I will show brief examples of what each of these learning designs looks like within curriculum‐making.

TABLE 8.3 Corresponding approaches to learning designs and curriculum‐making.

| Proactive | Intentionality in Deepening Critical Literacy Within and Across Curriculum. Creating systems in learning spaces that support children in moving through the world as researchers with a critical lens. |

| Responsive | The Inquiry Based Model. Kids serve you the hard information, i.e., the child brings their news/comments to the classroom. |

| Reactive | When Personhood Within the Community Is Threatened. An overt or implicit “ism” is experienced by a group of people or an individual based on their race, ethnicity, gender, or sexuality. |

The Proactive Approach: Intentionality in Deepening Critical Literacy Within and Across a Curriculum

This is where you create systems in your learning space that teach children to move through the world as a researcher with a critical lens.

- Create an audit trail. An audit trail is a visual articulation of learning and thinking that is meant to be visible not only to people in the classroom, but to others in the school community as well (Hartse and Vasquez 1997).

- Make your morning meeting a space where criticality lives. For example, students can adopt classroom jobs where they have a turn to surface concerns about the world that surrounds them, such as “Class Chairperson” (Vasquez 2004).

- Reshape morning workstations (Table 8.4) that allow kids to grapple with and learn more about named issues.

- In younger grades, this often will come from informal play experiences.

- Upper elementary students often will cite news they overhear family talking about, or they see on social media.

- Use protocols such as Sara K. Ahmed's “In Your News” where kids sharing news, whether it be difficult, banal, or silly, is routinized in daily classroom structures (2018).

TABLE 8.4 Morning workstations revised to create space for kids' lived experiences.

| Traditional Morning Workstations | Kids Experiences Are Assessed | Adjusted Morning Workstations |

|---|---|---|

Traditional morning workstations in lower elementary school:

| Adjustments are made to negotiate learning toward justice orientation:

|

The Responsive Approach: The Inquiry‐Based Model

This is when kids serve you the information, for example, the child brings the news or the “tricky topic” (usually unplanned!) to the classroom. Because inquiry‐style teaching is more of a stance than a “thing you can do,” I've included a specific example below that demonstrates this style of teaching from my own elementary school classroom, when I was frequently served “hard news.”

I was teaching fourth and fifth graders when the Pulse Massacre occurred in June 2016, and 49 people were killed at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The day after the shooting, the kids came in, and before we even sat down for morning circle, students were exclaiming: “¡Las arma de fuego!” Since it was June, and we'd been together for a full school year, the classroom community I'd cocreated with the students was strong. They knew that in our class we talked about things—even when other classes didn't. We always have options for how we choose to respond to students' questions, ideas, and wonderings. At this point in my career I was seasoned. I had strong teacher agency and a well‐developed stance in terms of who I was in the world as an educator. I was able to approach this experience from a responsive, active listening space, and inquiry‐based teaching was the mechanism I chose as a treatment toward justice. When kids come in the classroom space talking and saying phrases that include words like “gay,” “guns,” and “killing,” you do not skip over that energy and pivot into silent reading. Rather, you mentally note that students have witnessed a crisis, and they need help processing the bits and pieces they've heard.

The learning trajectory I took is described as follows. (And note, although this community was in New York City, many students came from conservatively religious families.)

First, I revised the schedule to make time for the heated talk. I knew if I didn't, the kids were still going to be talking about the shootings or thinking about them in another way. I also felt my “injustice” body alarms going off: hearing the kids' confusion and dark banter about the shooting was alarming. Queer people were part of our community, and I wanted them to understand how their statements had power to hurt and harm people.

Next, we gathered in our circle space, which we did every day for a variety of reasons. On most days, we gathered to engage in community building, sharing pieces of our lives, our hurts, our celebrations. This day, I engaged in direct teaching right away to clarify terms. As I noted before, many times in social justice education, literacy learning gets lost. In the circle space, I defined the terms, Queer, nightclub, and massacre. Not because I thought those are the types of tier‐two and tier‐three words that should be on upper‐elementary vocabulary lists, but because those were the words the students were saying over and over in the incorrect context, not knowing their full meaning. Kids mimic the grown‐ups who surround them, and their social comprehension models intersect all facets of life—media, family circles, random strangers they overhear at stores, friends, video game chatter. They picked this language up from somewhere, and at this point, it didn't matter from where. What mattered was that they knew the meaning of the language they were using. I am not talking about the inner workings of nightclub life, I don't need to talk about the type of dances or songs people listen to at Pulse nightclub. Again, I am directly responding to the news, words, phrases, and questions kids brought into the classroom space.

Then, I created space for questions. “Time for Questions” was a pretty typical experience for kids in our classroom. It was yet another ritual we held sacred to ensure everyone understood important elements of whatever discussion we had been engaged in. In general, but especially for difficult topics, kids want to know more. They are worried and they are wondering. In this particular scenario, the Queer community has long suffered at the hands of traditional schooling norms. If we are truly working toward justice, it is everyone's job to normalize talking about Queer life in the classroom just like you would talk about married life between a man and a woman in a classroom.

This style of inquiry‐based teaching isn't just like other literacy inquiry. Anytime you have an inquiry based on the nexus of one's humanity that some consider to be incumbent upon their identity markers, you will most certainly have to guard your inquiry with care. For me, I maintain that my open lines of communication with the families of the students I taught, as well as my colleagues, paired with strong foundational learning knowledge, allowed me to engage in conversations with my students that many teachers are not able to have. There was a level of trust between my students, their families, and my colleagues that ensured I was working to maintain the well‐being of the kid‐community. So, I invited community members in, we watched videos, and we read together. Myths about Queer life my students previously understood to be true were dismantled.

Imagine what would have happened if I ignored the heated conversation at the beginning of that day in June 2016? Queer educators often witness their humanity disregarded as their peers stay silent, as they witness books about families like their own being banned.

I haven't figured it all out. I know there are a lot of “what ifs” in regard to what's been banned, or what's not allowed. I try to live in the space of “let's try this” or “how can we work around that?”

Beyond the what ifs, most of all, I think about how this little collective of fourth and fifth graders began to grow their understanding about a group of people and moved from a space of misconception to one of empathy. That group was on a path to loving all peoples, and I felt lucky I got to be a part of that.

My friend Phil Bildner, author and writer of several middle‐grade novels that feature Queer characters, often tells his audiences: “No human being is inappropriate.” That phrase has carried me a long way, not because I believe there is anything inappropriate about a person's sexual orientation, but because, unfortunately, there are many people who do. When I am in conversation with these kinds of people, I center my language in research. Table 8.5 can support your engagements when you are dealing with homophobia, or any number of other “isms” in your school communities.

TABLE 8.5 The dangers of not talking about it with corresponding research.

| The Dangers of “Not Talking About It” | Corresponding Research to Support the Claims |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Reactive Approach: Personhood Within the Community Is Threatened

If your school community has not engaged in self‐reflective work, does not acknowledge the difference between “same” and “fair,” or does not have a consistent infrastructure to address the needs of teachers and students on a regular basis, chances are that someone's personhood has been threatened. Unfortunately, this reactive approach is fairly common because there are many school communities that fit the characteristics described above. However, it is better to say something after a harmful event has occurred, as there is more danger in not saying anything at all.

The work of standing up for those who have been threatened or harmed is enabled through your sense of purpose. Let's say that our purpose is to ensure that all children who participate in learning spaces are able to show up whole, feel valued in their full humanity, and honor others', especially those who have been historically marginalized. While I have many stories I have witnessed in this regard, they are the stories for other people to tell, from those who have been harmed. The following story has been told and shared widely. Professor Patricia J. Williams (2021) recounts threatened personhood in one of her recent essays on talking about race:

My son L. was invited to a neighbor's seventh birthday party. When we arrived, the neighbor child (R.) introduced L. to the small circle of other children, all of whom were white; he did so in hushed tones, seemingly so that adults wouldn't hear. “This is my friend L.,” he whispered. “He's Black!”

While this scenario is not my direct experience, it is representative of a great many witnessings through my life as a former elementary school educator, current parent of Black biracial children, and an educator who visits a lot of schools with hugely diverse student demographics. The teaching and learning I recommend (in the sidebar to follow) to use in the aftermath of an event such as the one described above are, however, derivatives of my own experiences in schools.

The Continuing Journey: A Constant Preparation (Not Necessarily Fun, but Definitely Joyful)

More often than not, I am of the mindset that binaries (the either/or thinking that so many parts of dominant culture amplify and prioritize), are not always applicable or universal to everyone's situation. I've talked a lot about the “packaged” nature of what “should” be done in school spaces for teachers and students that doesn't bode well for the general wellness of people in schools or learning outcomes for students. That said, I hesitate to insert the do's and don'ts columns in Table 8.6, but I recognize that blueprints are valuable in providing direction as people figure out their journeys toward justice. As you parse through Table 8.6, I encourage you to consider your role, your realm of influence, and also legal considerations that are part of your school community. Keep in mind: federal considerations such as those put forth in IDEA supersede what various individuals or community groups may request.

TABLE 8.6 Designing for justice do's and don'ts.

| Do's | Don'ts |

|---|---|

| DO: Anticipate pushback, and practice defending your position. Caregiver/parent to teacher: “You are indoctrinating my child.” Teacher to caregiver/parent: “In this school, we teach from a research‐based curriculum rooted in scientific understanding and childhood development.” | DON'T: Rely on a pre‐packaged social justice curriculum to do your work for you. Above all, this work is about honoring the humans in front of you, and helping them develop a critical, literate, moral core. Always be wary of any reenactment situation! Example: Pre‐curated “Culturally Relevant” libraries classroom libraries might not be expansive or targeted for students in your community. |

| DO: Approach the work with care. Work with a buddy. An affinity partner will work best in some cases. Stay connected to your students' families, and make it a point to be available and initiate consistent feedback (especially positive feedback!). | DON'T: Consider this work a separate subject, an exotic celebration, or a “one and done” project. Example: only teaching about Native Americans in the Fall or Black folx in February. |

| DO: Underscore the difference between kids, surfacing concerns that should be referred to a school counselor or social worker. All educators are mandated reporters. | DON'T: Quit! If you mess up, (and you probably will), don't stop! Keep going. Read more. Try again. Kids and families can be forgiving if you show your investment in long‐term justice. |

Note

- * Note, if you haven't established contact or any kind of relationship with the child's family, this work is going to be really, really hard. But you'll still have to do it.