CHAPTER 6

Age, Accelerating the Four Crises

First impressions upon landing in India are vivid. You are surprised by the diversity of vehicles and animals sharing the road, sometimes oxen and elephants with hordes of bicycles, motorbikes, three-wheel taxis, cars, trucks, and buses. But it is the pedestrians who approach you at the stoplights you notice most. The first time you see the deep brown, sad eyes of a girl in a tattered dress tapping on your car window, asking for any change you can spare, creates an indelible memory. You are struck by the dust on her dress, shoes, and hair, causing you to see the dust everywhere and realize you are sharing a two-lane road with six lanes of traffic. You are confronted by the number of people on bicycles or motorbikes who are in their twenties. They seem never to stop. How could the world have so many twenty-year-olds all in this one place?

The experience in Japan is quite different. If you are in a car, it may be the cleanest you have ever sat in, the driver has white gloves with no dirt apparent, and the roads are immaculate, wide and seemingly empty of people. If you have just arrived from India, your first question may be, Where are all the twenty-year-olds? Should you drive into rural areas, you may feel that you’ve entered a region of ghost towns; according to a 2013 Japanese government report, more than eight million properties in Japan are unoccupied, and nearly a quarter have been abandoned, meaning that they are neither for sale nor for rent.1 Scattered among the abandoned houses are old people with forlorn expressions; the young have fled to the cities. Many of the abandoned homes are unattractive to potential buyers because they have been the sites of suicides or “lonely deaths”—seniors who have died in place and remained undiscovered for often long periods of time.2

Demography Accelerates the Institutional Crisis

Demographics has created a time bomb for the world and we don’t have much time left on the clock to address it. The world population, which was just over three billion in 1960, has grown to just under eight billion. And these eight billion are sharply divided into two very different groups: one in countries whose populations are shrinking and aging rapidly and the other in countries that have large populations of young people. The result is a classic mismatch of resource and need. Even more important, age acts as an amplifier of the other crises, making all of them more urgent. The divide between rich and poor, both in and across nations, becomes greater. Disruption of society accelerates as labor forces and tax bases in older countries dwindle, while unemployment and unrest in younger countries grows. Young migrants seeking opportunity stoke the fires of populism among older populations. The failure of institutions to address the pressing needs of either group feeds the crisis of institutional legitimacy around the world.

At the extremes there is a more than thirty-year gap in median age between the world’s oldest and youngest countries.3 It is mind-blowing to think about a three-decade difference between the median age of given countries. There are not just a few countries on either side of this gap. There are fifty countries with a median age over forty and thirty-seven countries with a median age under twenty. That is roughly one-third of all the countries reported in the CIA’s World Factbook. Japan is the third-oldest while India is the eighty-sixth youngest, but many of the youngest countries are in Africa. In Europe such countries as Italy and Greece are aging at an even faster rate than Japan.

FIGURE 6.1 Share of the population age sixty-five or older, 2010 and 2050 (percent). NOTE: Caribbean countries are included in Latin America. SOURCE: United Nations Population Division World Population Prospects, 2012 Revision.

At the broadest level, nations like Japan are those with a rapidly growing population of elderly citizens; these countries tend to be more affluent overall and there is a well-established correlation between affluence and declining fertility rates. They enjoyed extraordinary success under the economic model much of the world adhered to for seventy years and remain wedded to that model as a solution for their problems rather than reframing their thinking for today’s challenges. Conversely, young nations are less affluent and tend to have much higher fertility rates. Their leaders see the immense risks associated with a young population needing education and economic opportunity, but they have neither the funds nor the systemic vision to address these risks.

Despite the appearance of two very different worlds as shown in Figure 6.1, there is of course only one, and the problems of the youngest populations and the aging populations are a recipe for disaster for all of us. Let’s take a look at how age augments, amplifies, and accelerates the crises and poses different challenges for institutions in old and young nations.

Age and the Prosperity Crisis

In developed older economies, age and asymmetry compound each other in many ways; a good way to get a sense for how massive the problems are—and how they are threatening to bring many of these economies to their knees—is to look at old age dependency ratios. Every country in Figure 6.2 has a median age over forty. A ratio of 100 percent would mean that there was one person over sixty-five for every person in the workforce. For most of the twentieth century, every one of these developed countries had a ratio of less than 25 percent, but by 2030 all will be north of 35 percent, with Japan over 50 percent. This spells disaster for these nations by 2030 unless something is done. Why? Because most of these economies have relied on those in the fifteen to sixty-five cohort to supply the labor and the consumption upon which the economies run.

At the same time, these people saved money for retirement, contributed to various public and private pension schemes, paid taxes to fund services for seniors, and directly supported their elderly relatives. The skyrocketing old age dependency ratios illustrated here have pulled the rug out from under this system. Not only is the sixty-five-plus cohort growing in number, but they’re living longer too. For far too many of these senior citizens, personal savings are proving inadequate as the portion of life spent in retirement and typically in less robust health grows longer. Welfare systems and social safety nets, which these people contributed to, or at least counted on, were designed with a different set of assumptions about how many would call on those systems for support and, critically, for how long they would be dependent on them. With both savings and support systems proving inadequate to the needs of the older population, many of the elderly are falling into poverty or near-poverty.

FIGURE 6.2 Old age dependency ratio, select developed countries, 1950–2050. NOTE: Ratio of population aged 65+ per 100 population 16-64; UN Medium Variant. SOURCE: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

Meanwhile, the burden of supporting the elderly weighs on a shrinking labor force. The result is that workers are facing higher taxes paid into the system, whether they be for pension and welfare schemes or to subsidize healthcare costs; increased calls for financial help from elderly relatives; and decreased ability to put aside money for their own retirement. Affluent citizens in these economies benefit from generous retirement plans, healthy investment portfolios, and appreciating real estate values; it is these very people who tend to fill leadership positions in government and business. They are insulated from the problems most citizens face and thus don’t bring the proper sense of urgency to these problems, but these pressures from an unfavorable dependency ratio are contributing to the hollowing out of the middle class. With old age dependency ratios increasing into the foreseeable future, this downward spiral will only become worse, contributing to further inequity and dysfunction.

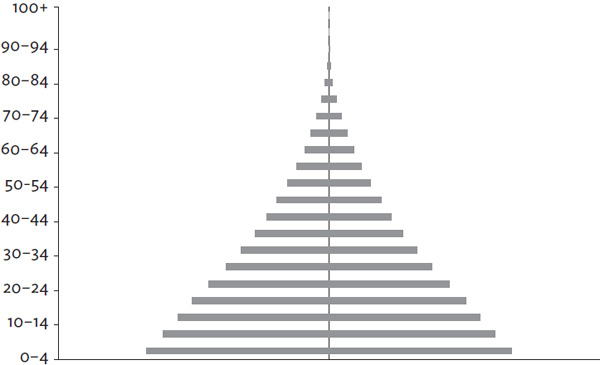

FIGURE 6.3 Sub-Saharan Africa population by age, 2030. SOURCE: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

And what of the developing economies with much younger populations? As has been mentioned and shown in Figure 6.3, Africa is home to many of the nations with the world’s youngest populations. According to the 2020 CIA Factbook, there are thirty-one countries where the median age is under twenty years old.4 Of those, twenty-eight are in Africa. By the UN’s estimates, these African nations had a total population of 866 million in 2015; by 2030 that number is expected to grow to 1.29 billion, of which 261 million will be between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four. This represents a huge number of people who will be in need of education or meaningful employment. By UN estimates, in 2030, Nigeria alone will have nearly 54 million people in the fifteen to twenty-four age cohort, while Kenya will have more than 13 million. In part, this enormous challenge is due to what most people would consider to be good news: childhood mortality in Africa has dropped precipitously in recent decades, as it has in much of the world.

In the past, these nations might look to developed economies to provide aid in the form of funding or loans, but with developed nations increasingly beset by the age-driven or age-exacerbated problems described above, help may be less likely. Among those developed nations that see it in the interest of the global economy to help any way they can, the sheer size of the problem is daunting at best and insurmountable at worst.

Age and Institutional Disruption

Younger developing nations like those in Africa are likely to be deprived of what has been a stepping-stone to establishing a middle class in the late twentieth century: labor arbitrage. As a true global economy developed after World War II, industrial corporations from developed countries found that they could lower the largest component of manufacturing (labor costs) by setting up locations in countries with low labor rates. This phenomenon had obvious benefits for the home country but also provided important sources of employment in younger developing nations. These enterprises gave local workers the opportunity to learn and copy. Taiwan and South Korea, to name but two examples, grew rich by following their “workshop of the world” strategies. However, as artificial intelligence and robotics sweep the manufacturing sectors of most developed nations, this well-trodden road to bolstering a middle class may be disappearing, leaving nations like those mentioned in Africa, as well as populous, youthful nations like Indonesia, with fewer options at the very time when more are needed because of their growing youth population.

Moreover, economies that have made some progress already providing offshore labor to the developed world are seeing erosion of jobs in those sectors. For example, if we look at who is most likely to be affected in India’s highly lucrative IT outsourcing business, it will be the least skilled and thus those least able to find other work. Over the next decade we’ll see robots doing the entire job of some skilled workers as well.

If technology has disrupted business models and industries around the world, age is an equally potent disrupter of institutions, infrastructure, and societal norms. In developing economies, where educational systems have often struggled to make a notable difference in terms of employment readiness to even a small slice of the population, the huge increase in young people brought about by declining childhood mortality rates and fewer instances of extreme poverty now takes the form of a tsunami threatening to swamp all in its path. Even those who have worked hard to improve literacy will struggle to keep up. In Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous country, where the median age hovers around thirty, twelve years of education are compulsory, yet most of the population is functionally illiterate. India, soon to be the most populous nation on earth, believes it will need to build more than half a million new schools by 2030.5 It’s easy to see that the cost of infrastructure required by these burgeoning young population cohorts is immense. Across the developing world, young people are streaming into cities that were built for much smaller populations. The consequences of not meeting these needs are high unemployment, depressed economic growth, social unrest, and increased emigration—especially of the best and the brightest.

In older developed nations, age is equally disruptive but in different ways. First, automation in the workplace threatens to further undermine the ability of the labor force to carry its senior citizens. PwC has estimated that developed nations may have anywhere from 20 percent to just under 40 percent of current jobs at risk of automation in the next fifteen years. Of course, new jobs will be created as well, but the biggest question will be whether those who have lost jobs to robots and AI will have the skills to fill the new positions. In any event, significant job loss will result and those displaced by automation will find themselves competing for social safety net funding with the burgeoning elderly population—at the same time that those funds are put under greater pressure because of a diminished tax base. The aging tax base threatens to squeeze funds for infrastructure investment in older nations, where in many cases the need is enormous; many developed nations, including the United States, are faced with crumbling cities, roads, and bridges built for a different time. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the American Society of Civil Engineers has estimated that the total infrastructure gap in the United States will reach $1.5 trillion by 2025.6

Meanwhile, the healthcare systems in many older countries are already struggling to handle the growing legions of retirees. Healthcare costs per capita are skyrocketing throughout the developed world; the ten largest OECD members have seen this figure in United States purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars increase more than 160 percent over the past two decades.7 The growing healthcare sectors in these countries are of course a source of employment for those displaced by automation elsewhere, but pay is often lower than what could have been earned on the factory floor.

![]()

Clearly, the challenges outlined in the first part of the book are enormous and seem too overwhelming to successfully corral. If we try to employ answers copied directly from those who guided us in the post–World War II period, we will be relegated to watching or, worse, participating in exacerbating our problems and cause irreversible harm. A better approach—an imperative one—is to adapt the underlying ideas from the model that helped generate so much success to address their unintended consequences. Exploring those new solutions is the job of Part 2 of the book.