PART I

HOW WE GOT TO THE PRECIPICE

IN LIFE THERE ARE INFLECTION POINTS WHERE INACTION LEADS to the dramatic acceleration of something bad, but the appropriate action can produce a really good outcome. The world is at just such a point and we do not have much time to make the right choices and take the right steps.

The irony is that what has brought us to this inflection point are the forces that gave the world decades of amazing success. Since around 1950, in at least the Western, non-Soviet portion of the world (as well as in many countries with populations that aspired to be a part of it), we had generally agreed ideas emerging from the embers of the Second World War that guided us in confronting the challenges and taking advantage of the opportunities unique to the time. However, we became complacent and self-satisfied. As the years unwound, we lost the will to question the efficacy and outcomes of the choices we made after the war, and we failed to notice the ways in which technology and other forces were changing the systems we had built.

That was an enormous mistake. Today the consequences of our laserlike fealty to a graying world order are coming into disturbing focus: a set of extremely complex, far-reaching, and obstinate global problems that are already beyond simple responses. Indeed, because we have so far failed to credibly identify these problems—much less address them with urgency and new, imaginative answers—they have begun to mutate into dangerous crises. Crises that we must resolve now.

Throughout this book I describe these challenges in some depth and offer creative solutions. I came to identify these crises through an interesting route. Based on a general sense that the world had become a worrisome place, I visited with leaders in politics, business, and civil society as well as with individuals in coffee shops, hotels, schools, airports, buses, and taxis around the world. I asked them how they were feeling about the future. I learned that people were very worried and they all had consistent deep concerns. To summarize these repeated worries, my team and I coined the acronym ADAPT:

![]() Asymmetry. Increasing wealth disparity and the erosion of the middle class.

Asymmetry. Increasing wealth disparity and the erosion of the middle class.

![]() Disruption. The pervasive nature of technology and its impact on individuals, society, and our climate.

Disruption. The pervasive nature of technology and its impact on individuals, society, and our climate.

![]() Age. Demographic pressure on business, social institutions, and economies.

Age. Demographic pressure on business, social institutions, and economies.

![]() Polarization. Breakdown in global consensus and a fracturing world, with growing nationalism and populism.

Polarization. Breakdown in global consensus and a fracturing world, with growing nationalism and populism.

![]() Trust. Declining confidence in the institutions that underpin society.

Trust. Declining confidence in the institutions that underpin society.

One worry I was surprised people didn’t raise in our conversations was fear of a pandemic. When trying to find a path through the issues addressed in ADAPT, a pandemic would generate two new concerns: how to recover and prepare for the next one and how to deal with the very real political and economic consequences of the decisions taken to address it. It would be another massive disruption, and we would need to accommodate ourselves to its impact just as we will to the other forces described in this book. Indeed, a pandemic would cut across all the elements of ADAPT and risk accelerating them by, for example, hastening the increase of disparities within and between nations and causing a deeper questioning of the trustworthiness of the institutions we have built to manage our lives.

But just singling out these shared worries without using data to determine whether what people are worried about is actually cohering into a legitimate crisis was not sufficient. Thus, joined by the other authors, I set out to examine more concretely these recurring concerns. The result of that work is Part 1 of this book.

We learned that the ADAPT framework was on to something very real. The combination of wealth disparity, the perils of technology, countries aging at different rates, the breakdown in society, and the loss of trust is behind the emergence of four crises: a crisis of prosperity, a crisis of technology, a crisis of institutional legitimacy, and a crisis of leadership. Moreover, as each crisis worsens, it poisons other elements of ADAPT, multiplying the negative impact. ADAPT and its associated crises blend together into a pernicious system.

If we allow disparity to widen and sustain for too long, the risk is that a large number of people will simply give up, thinking that their lives will never improve. But prosperity requires the opposite: that people believe in the future and thus energetically create, work, invest, and build. When belief is lost, innovation to improve society diminishes and technology becomes less of a force for good. This, combined with young countries having limited opportunities to offer their youthful, working-age populations, can lead to unrest, which spreads quickly around the world.

If we are not prepared to manage the negative consequences of ubiquitous technology or develop technology that elevates our cultures, our capacity for cooperation, and our lives, society irreparably splinters into large and small cliques born of self-protecting individualism. To take advantage of these riven societies, political leaders on all sides promote unyielding partisanship rather than thoughtful, inclusive ideas that can improve the lives of many rather than a small base of constituents. In this environment, institutions are neglected or even actively undermined, lose their relevance, and are used as political pawns, even though they are essential to the effective functioning of society. If we continue to fracture in this way and lose faith in the future, society, our leaders, and our institutions, essential changes that can eliminate the pall that hangs over us will never occur.

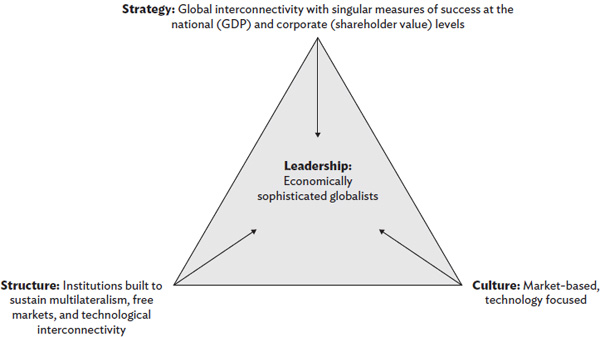

FIGURE P1.1 The shared global alignment that drove seventy years of success following World War II. SOURCE: Created by the authors.

To explore more concretely how we have arrived at this inflection point (and what we should do about it), it is useful to view change through a simple model that I have drawn upon throughout my career as a teacher, leader, and adviser (Figure P1.1). To transform an organization, institution, even a society, four elements must be aligned: strategy, structure, culture, and leadership.

In the wake of World War II, the economies of countries around the globe were decimated and needed to be rebuilt from the ground up. Led in large part by the United States–backed Marshall Plan, which provided the money for European nations outside of the Soviet sphere to put their most severe economic woes behind them, a globally interconnected economy was spawned for the first time, based on this transformation model. The elements broke down this way:

![]() Strategy. Drive globalization and interconnected market economies using these metrics of success: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for countries and shareholder value for companies.

Strategy. Drive globalization and interconnected market economies using these metrics of success: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for countries and shareholder value for companies.

![]() Structure. Build institutions to support growth of GDP and shareholder value as well as the principles of this change model, emphasizing free markets, multilateralism, and technological interconnectivity.

Structure. Build institutions to support growth of GDP and shareholder value as well as the principles of this change model, emphasizing free markets, multilateralism, and technological interconnectivity.

![]() Culture. Operate to maximize the success of markets as defined by very specific measures and continually strive for the next technological innovation to promote efficiency and effectiveness.

Culture. Operate to maximize the success of markets as defined by very specific measures and continually strive for the next technological innovation to promote efficiency and effectiveness.

![]() Leadership. Develop people to become economically sophisticated globalists, placing emphasis on GDP and shareholder value as the key metrics determining a leader’s success and expanding influence across the world.1

Leadership. Develop people to become economically sophisticated globalists, placing emphasis on GDP and shareholder value as the key metrics determining a leader’s success and expanding influence across the world.1

The years 1986–1992 represented a watershed period when this global network model became turbo-charged. In 1986 the City of London was deregulated, which in turn led to a massive liberalization of capital markets everywhere. Two years later, the World Wide Web was created, unleashing an open electronic communications and information forum that would facilitate in ways never before seen global interaction and innovation. In 1989 the Berlin Wall fell and a host of new countries that had been behind the Iron Curtain developed some form of market economy and entered the global community. Three years after that, Deng Xiao Ping’s “southern tour” ensured that China would adopt market-based reforms and global trade as the foundations of its economy, unleashing unprecedented growth in the world’s most populated country.

Until 2007, this model seemed to be working, at least on the surface (Figure P1.2). Global GDP grew at a remarkable rate, bringing billions of people out of poverty, creating significant wealth throughout the world, and increasing overall health and well-being. In the two decades since the late 1980s more than half the world’s population had entered the global economy, buoying developing countries as well as the developed countries to which they sold their products and services.

FIGURE P1.2 Economic and social progress since 1960. SOURCE: databank.worldbank.org.

But the financial crash in 2008 and the ensuing worldwide recession revealed the emerging dark underbelly of that success, which had been lost in the euphoria surrounding the postwar economic and social advances. The downturn brought out of the shadows the many people who were not receiving benefits from the global economic order anymore and the disconnect between them and the more privileged individuals and entities still profiting. The collapse in equities, housing, and capital markets swelled the ranks of the disadvantaged, making them even harder to ignore. This post-2007 period is when the global problems and people’s worries identified by the ADAPT framework began to make themselves known. To further explain:

![]() Asymmetry. One of the gains of globalization was that labor rates were normalizing around the world. This was great for people in emerging nations and for owners of capital in developed nations, but not for those who lost their jobs or who had stagnant wages due to globalization in places like France, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States, where manufacturing used to be a desirable job with decent salaries and benefits. At the individual and regional levels, globalization was a core cause of asymmetry.

Asymmetry. One of the gains of globalization was that labor rates were normalizing around the world. This was great for people in emerging nations and for owners of capital in developed nations, but not for those who lost their jobs or who had stagnant wages due to globalization in places like France, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States, where manufacturing used to be a desirable job with decent salaries and benefits. At the individual and regional levels, globalization was a core cause of asymmetry.

![]() Disruption. Rapidly accelerating technological innovation has caused disruption in many ways. The Internet helped create global platforms for economic exchanges and transfer of information, thus spawning new businesses and increasing efficiency dramatically. But it also disrupted traditional industries, which had often employed the people whose lives had already been harmed by globalization. In addition, advancements in technology that have made our lives easier have accelerated climate change and threatened our very existence.

Disruption. Rapidly accelerating technological innovation has caused disruption in many ways. The Internet helped create global platforms for economic exchanges and transfer of information, thus spawning new businesses and increasing efficiency dramatically. But it also disrupted traditional industries, which had often employed the people whose lives had already been harmed by globalization. In addition, advancements in technology that have made our lives easier have accelerated climate change and threatened our very existence.

![]() Age. Such upheaval in the job requirements in major industrial and service sectors is just one of the ways that age (countries with populations that are increasingly too old or too young) exacerbates the challenges inherent in the ADAPT framework.

Age. Such upheaval in the job requirements in major industrial and service sectors is just one of the ways that age (countries with populations that are increasingly too old or too young) exacerbates the challenges inherent in the ADAPT framework.

![]() Polarization. While simple measures such as shareholder value for organizations and GDP for nations offered an easy way to keep score and make capital investment decisions, they also created a singular focus on economic success to the exclusion of social well-being, missing the very real problems being experienced by large swathes of people who became disenfranchised. This led to increasing polarization, which was amplified by the unintended consequences of technology.

Polarization. While simple measures such as shareholder value for organizations and GDP for nations offered an easy way to keep score and make capital investment decisions, they also created a singular focus on economic success to the exclusion of social well-being, missing the very real problems being experienced by large swathes of people who became disenfranchised. This led to increasing polarization, which was amplified by the unintended consequences of technology.

![]() Trust. As disillusionment has grown and optimism about the future has ebbed, institutions (a wide-ranging term that includes tax systems, universities, the police and the military, and government agencies, to name just a few) have struggled and often failed to offer any solace or stability to people caught in the crossfire of these negative trends. That has precipitated a perilous loss of trust in institutions and leaders.

Trust. As disillusionment has grown and optimism about the future has ebbed, institutions (a wide-ranging term that includes tax systems, universities, the police and the military, and government agencies, to name just a few) have struggled and often failed to offer any solace or stability to people caught in the crossfire of these negative trends. That has precipitated a perilous loss of trust in institutions and leaders.

It is an intriguing accident that for each of these crises, we have ten years to respond: billions of African youths will reach working age by 2030; the protests ranging from the Gilets Jaunes to those in Hong Kong are harbingers of larger protests and global fracturing to come; continued inaction toward climate change for ten more years will likely produce irreversible consequences; large groups of retirees that will make big demands on government budgets will predominate in ten years; institutional failure will be at a breaking point in ten years; and technology platforms and their consequences will likely have rewritten the rules of manufacturing and most service industries by 2030. We have ten years to midnight. And the clock is ticking.

It is not that we have ten years to start the process of solving these crises. No, we have ten years to mostly address these crises. This will not be a simple task. It requires completely rethinking assumptions that for upwards of seventy years seemed self-evident. We have to reframe our ideas about political economies, reshape the institutions that once made our societies work, rein in technology and platforms that harm us while elevating the good, and find a way to bring a fractured world together. And do all of that at a scale that is rarely addressed over centuries, let alone ten years.

Part 2 of this book offers some solutions we could adopt to address the crises. They are not exhaustive—many more people and many more ideas will be needed to address all the challenges the world is facing—but they are a start. None of the solutions we propose works on its own; together, they form a system. Without addressing each crisis, we will fail to make progress on all of them as a cluster. Any individual or organization might, of course, focus on one or other of these potential solutions, because it is more relevant to the particular circumstances they find themselves in. As global citizens collectively we need to perceive of them as a group.

These chapters can therefore be thought of as a proposal to reframe the dominant logic still driving after all these decades our concepts of growth in the world, countries, regions, cities, and organizations. Certainly we should retain the basic elements of the past seventy years or so that still serve us well. But we should eliminate strategies that produce only negative outcomes now; we should update our thinking, our institutions, and our behaviors to attend to the very different realities that we face today.

As you read this book and give some thought to our collective worries and their associated crises, keep three things in mind. First, these are shared concerns that may vary in form around the world, but they are pervasive, affecting us and people in our communities everywhere. Thus solving them will require the participation of leaders and citizens from places big and small. It is not useful for people in one region to punt on a problem because they are not the primary cause of it.

Second, realigning global attitudes to a more shared and cooperative vision, as that vision is evolving today, will take time. Yet some of these issues are very big and strikingly urgent. They cannot wait for a new system of ideas and global relationships to emerge before being confronted. Hence, to borrow an oft-used analogy, we have to rebuild the plane while we are flying it. Even as we immediately address the most urgent issues, we must design solutions that accelerate the development of equally important long-term and ongoing needs, such as building and reinvigorating essential institutions, forging shared cultural and social bonds, rekindling innovation for social good, and reviving support for imaginative and open-minded leaders.

Which leads to my third point: solving today’s global crises will involve steering through apparent paradoxes. We need to do things that may seem inherently at odds with each other. Let me offer two examples. In Part 2, I argue that we must place a much greater emphasis on local economies and politics than we do now. Yet we cannot ignore enormous global issues that are by definition too large and interwoven throughout every region in the world to be managed by local efforts; nor can we neglect the wider interdependencies that even local programs must navigate.

Similarly, if we hope to build technology that enhances the global community and serves as a bulwark against the challenges that can harm us, we need to develop in schools and organizations people who are technically capable but also studied in human nature and how systems facilitate and impact our lives. Generally we are not doing that now. How many engineering programs do you know that also teach sociology, political science, and psychology? How many humanities students also have expertise in computer science and engineering?

With these rules of the road in hand, let’s see where this takes us. As you learn about our shared worries and the precipitating crises, it is my hope that ideas for action will surface so that the solutions will jumpstart, influence, motivate, and boost the steps that you are already thinking of taking.