Stage two: Clarify

The wise man doesn’t give the right answers; he poses the right questions.

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Once your client has been emotionally and contractually engaged, you need to move beyond what is a relatively narrow field of vision. The goal is to take away some of the haze – to understand the real source of the problem. Only then can you make a firm proposal as to how the situation can be resolved.

It is at this stage that the first dilemma can occur. Often a client will employ you because they have a problem that is urgent and pressing. When the wolves are at the door it is difficult to suggest that your client should set aside time for detailed diagnostics. With a client in panic mode you may be expected to be in the same frame of mind. The expectation is that you will be able to walk in, fix the problem, take the 50 pieces of silver and then let the organization carry on with its affairs.

If you are being paid on a daily rate and employed solely to deliver a focused outcome, your client may well regard activities such as investigation, research and diagnosis as wasteful (and unnecessarily expensive). This is because they (often) think they know what the cause of the problem is already – you are just expected to fix it. But even when time is of the essence, the same underlying disciplines and rigour need to be applied so that errors are not made. Rushing in and attempting a quick-fix is as dangerous as a doctor prescribing an operation based on the patient’s own diagnosis.

You have a legal responsibility to deliver an agreed outcome and you also have an ethical responsibility to deliver the ‘appropriate’ one. Prescribing a solution without correctly diagnosing the cause of the problem may offer short-term income but leads to long-term erosion of your market credibility. If clients realize that a consultant’s solutions do not result in a true resolution of their problem then the jokes about consultants become perpetuated.

The process described in this stage of the Seven Cs model follows this pattern.

- Situation blindness – it can often be hard to get to the real issue or heart of the problem because people operate in a semi-delusionary state where they fail to see, understand or accept what the world is really like.

- Diagnosis – gather information that will help determine the real source of the issue and not just tackle the symptoms.

- Phase mapping – determine the extent to which known and unknown factors within the change process will affect its potential for success.

- Shadow dancing – determine the extent to which unspoken activities and arrangements will affect the situation.

- Culture – understand the cultural factors that affect the change process.

- Decision makers – be clear about who is actually making the decisions, as opposed to who says they are.

- System construction – understand the structure of the organizational system and how it is likely to react to any changes.

- Stakeholders – develop a map that indicates who can influence the outcome of the change and to what extent they have the capability and desire to wield their power.

- Life cycle risk – gauge the level of risk associated with the project.

If we follow these components in the Clarify stage, it becomes possible to ensure that the Create and Change stages actually resolve the source of the problems rather than simply eradicate the evidence.

Situation blindness

One of the initial and changing aspects of the diagnostic stage is ironically to help the client accept that there is a problem. Many clients will call a consultant in and want to move them directly to the Create or Change stage – on the basis that ‘they already know what the problem is!’ This might be akin to the person who repeatedly tries the latest smoking, diet or health product. They believe that they know what the problem is and so want to rush to fix the solution.

When called (or sent) in to resolve a problem it is not unusual to hear the following statements from the clients, stakeholders or line managers:

- ‘There is no problem, I can’t see what the fuss is about.’

- ‘I can see there is a problem but it really isn’t important.’

- ‘It is important – but there is no solution.’

- ‘There is a solution – but it is too difficult.’

- ‘It can be fixed but I am too busy to deal with it at the moment.’

‘Situation blindness’ can be described as a process by which clients, stakeholders and consumers minimize or maximize an aspect of reality for themselves or others. They have created a world that suits the one they want to see and excluded or discounted the idea that an alternative situation might exist.

An example of this can be seen in the smoker who discounts the health issues (even to choose not to read the large health warning on the packet), the drunk driver who believes they become a better driver after three pints or the obese person who looks in the mirror and sees someone who is slim. We can see the same human process in the corporate and business world – almost on a daily basis. Pick up a newspaper and on most days you will see examples such as:

- the organization that has ceased trading because they lost touch with changes in the market conditions;

- the local politician who cannot see the writing on the wall for their tenure and their imminent departure as voters look to select an alternative party;

- the senior politician who believes that a slight indiscretion in their spending will not be an issue with the general public;

- the airline company that accepts that their customer service capability is not so good only when a disgruntled customer sets up an alternative website or posts a sarcastic video on YouTube.

In all these cases, people who sit outside the situation can obviously see what the issue is (like watching Big Brother or TV soaps) but the player in the situation is blind to what is going on. The challenge for the consultant is how to deal with a client who has such blindness and doesn’t want to let go of their safe delusionary state. In other words they are not accounting for the reality of themselves or others or the situation. So in effect the blindness is actually distorting reality in presenting things in a way that helps the person feel more at ease (in the short term).

Shine a light

When faced with a client who is demonstrating signs of situational blindness, it might be best to give it to them straight – tell them to (as my daughter would say) just deal with it and then move on. The risk behind this is that like walking from a dark room into a light room – the experience can be painful, cause an adverse response and initially actually make the blindness worse. The consultant’s role is to make friends, not enemies and so upsetting the client or key stakeholder in the Clarify stage of the Seven Cs doesn’t really work that well in a live situation. The goal is to never drag towards, tell or get someone to see a new way of looking at things – rather it is to help them to choose a new way.

The first step in seeking to shine a light on a problem is to understand what level of blindness the client has with respect to the situation. We can do this by reference to five levels of situation recognition:

- Level 1 – no problem recognized;

- Level 2 – problem recognized but not deemed to be important;

- Level 3 – important but there are no solutions;

- Level 4 – solutions possible but don’t know how or don’t want to do it;

- Level 5 – clarity of the situation and willingness to address.

In seeking to test where the client is on this scale, it can help to structure your questions around the levels. So in working with a manager to address a problem of low performance the consultant might structure the conversation in such a way as follows in Table 5.1. First all of we need to test to see if the client recognizes the problem or external stimuli.

If the client answers ‘Yes’ all the way through the levels then you will get a strong indication that he or she is not blind to the problem being addressed. But if in the process you hit a ‘No’ then this might be the area in which the blindness is occurring, and that area needs addressing before moving on in the Seven Cs process.

So the hardest case might be the client who blocks a level 1 question with a view that they do not see any problem. At that stage, as the consultant you have the interesting situation where you have been asked to work with a client who is blind to issues that need to be addressed. If you get a level 2 statement where the client accepts that there is a problem but not one that is important enough to deal with, then you have a challenge of prioritization. How do you get the client to accept that they might need to make time to address the issue? A level 3 ‘no’ indicates that they see a problem, recognize the importance but believe it can’t be fixed. There is a sense of permanence for them in ‘that’s how it is’. This can be a common blocking level in organizations that have been in operation for some time and people have locked into familiar patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving. A level 4 block is where the client sees the problem, knows it is important and can see ways to fix it – but either doesn’t want to or doesn’t understand how to move forward. At level 5 the blindness has gone and the client chooses to see the problem for what it is and begin the process to correct it.

The net result is that with the aid of a few very simple but structured questions the consultant can rapidly test the client’s situational awareness and gauge the extent to which sustainable change will be viable. This is based on a very simple pretext – if the client is blind to the truth of their current situation then there is little chance that they will be able or willing to fully engage in any proposed change.

Open the blinds

In simple terms, the aim of the consultancy conversations must be to have a level 4 recognition as soon as practically possible in the engagement – with the client, consumers and other critical stakeholders. Although this might sound relativity simple, just think how much money has been spent on smoking, drug and drink health awareness promotion and how much people simply learn to turn out any message that doesn’t fit with their desired map of the world. The golden rule for me is that unless you have some type of deep mind-control capability over the client – you can never ever ‘GET’ them to level 5 recognition. It has to be something that they choose to do. The skill is in influencing the client to make that choice in a pain-free way.

Before we look at how to influence this outcome, it can be useful to understand and map what type of consulting conversation can often happen. The first thing to recognize is that aligned conversation can be very comfortable and attractive. So two people having a level 1 conversation would have a nice easy chat about how great life is. This might be along the lines of ‘isn’t it wonderful that with the new loan in place we are rich and money won’t ever be a problem again’. It can be a delusional state that feels comfortable for both parties – but the reality will hit home at some point. A level 2 conversation is driven by talk about problems that exist but are not important. This might be a conversation in which a married couple talk about the fact that home costs are increasing and they are running over budget – but it is something that is beyond their control because of the increases in the cost of living. A level 3 conversation with the same couple has them talking about how they need to save money, but it is not possible because they still have to live!

In all these examples the conversation will feel comfortable for both parties because the patterns are aligned and complementary. Where parallel conversation occurs then the pattern will be simple – the challenge can be when the conversation is initiated from different levels. This can lead to stress in the relationship and is one to be very careful about.

The interesting point is that while the consultant may operate at a parallel level for a while to help to develop a feeling of easy rapport with the client – at some point the consultant has to develop a strategy to help get to a level 5 conversation. The risk is that if the move to that level is not done with ease or effectiveness then it can jar the relationship creating problems and causing tension in the relationship. However, the act of operating at a different level to the client can trigger certain responses that are of value.

This is not to say that the consultant should not deliberately use a level shift and knowingly create tension – this can be a powerful way of challenging the client. The argument is that such a shift should be a conscious move and not left to chance. The ideal option is to have a range of strategies that enable the consultant to gently ease the conversation up to level 5. These strategies should always be underpinned by a series of key principles and conventions.

- Level ownership – you can’t own the client’s conversation. Although you may seek to influence the way they see the world and the language they use, you have no gift from God to move them to another level. The key thing is not to get frustrated if they choose to be at level 1 or 2 and try to accept that if that is how they choose to view the world then that is their prerogative.

- Level shift – if you plan to shift a level during a conversation then doing it in a false way will in most cases be seen as such by the other person and will tend to make things worse. If you want to shift levels then practise and practise again so that you are able to effect a change seamlessly and effortlessly.

- Level filter – beware when you make assumptions about where the other person is – there will be a chance (strong one) that you are discounting aspects of their patterns to suit your needs and so distorting and corrupting how you are analysing them. It always makes sense to ask yourself why you are making this assumption and how do you know it is true?

Techniques for shifting

The first rule is that if someone wants to be led to their predicament then they will be. No consultant has the absolute power to ‘GET’ someone to see the world in a new way. But where there is a clear invitation to the consultant, with intent to change, then it is very possible to help the client to see their problem in a very new and original way.

So often, the greatest gift that a consultant can offer a client – is not a resolution of their problems – rather it is the gift of an objective viewpoint. When offered with honesty, integrity and care it is one of the greatest interventions that any consultant can offer a client.

Diagnosis

At this stage your primary objective is to discover timely, robust and accurate data. However, before you can start to collect data you must make a methodological decision about the approach you are going to use. There are many schools of thought behind the process of data gathering and research but two common models are the outside-in and inside-out models.

Outside-in model

The outside-in model is based on the idea of prior hypotheses. Data is collected against a predetermined model or mental framework. You will be trying to prove or disprove a specific argument or develop a test bed for future expansion. A strategist might use Porter’s five-forces model (2004) as a tool to understand a company’s strengths in the market; an organizational development consultant will use Lewin’s force-field tool (1951) to map and understand what negative and positive forces are operating in the organization; the marketing consultant might analyse the company’s product-positioning against the portfolio positioning tool. You are working on the assumption that a predefined model or paradigm can help to identify a clear solution to a problem. This type of research is driven by the following assumptions.

- Hypothesis – a predefined model is used as a guiding framework to drive the data-gathering process.

- Independence – there is no subjective bias. The data sits on the table and is manipulated without being clouded by your personal views.

- Value-freedom – objective criteria rather than human beliefs and interests determine the choice of what to study and how to study it.

- Operationalism – concepts need to be operationalized in a way that enables facts to be measured quantitatively.

- Reductionism – problems are better understood if they are reduced to their simplest elements.

- Generalism – in order to generalize about regularities it is necessary to select sizeable samples. Once a statistically sound sample is used then any conclusion drawn from the process is applied across the entire population.

Inside-out model

The alternative approach is built around an inside-out, or grounded, model. With this model the research process is open-ended and uncluttered by the mental framework of the consultant. Any output will be guided purely by the content of the data. This model uses a set of principles that are quite different to the outside-in model.

- Natural setting – realities cannot be understood in isolation from the context in which the study is undertaken. So although Porter’s five-forces model is suitable for the areas Porter studied, it might not be applicable in all contexts.

- Human instrument – only humans are capable of grasping the variety of realities that will be encountered. Rigid and structured data-gathering processes will be unable to pick up the minor nuances of inflection that can indicate so much, for example during an interview.

- Use of tacit knowledge – intuitive/felt knowledge is used to appreciate the existence of multiple realities and because it mirrors the value patterns of the investigator.

- Qualitative methods – the use of words rather than numbers makes the data more adaptable when dealing with multiple realities and patterns and influences.

- Emergent design – it is impractical to assume that you know enough ahead of time to build a research design that could capture all the necessary data – the research process must emerge with the findings from the data.

This approach operates on the basis that discovery and diagnosis is not a black and white process. Since most data-gathering will involve people, there is a good chance that the process will be full of uncertainty, emotion and confusion. The data-gathering process needs to be built around an emergent rather than a fixed design.

Diagnostic process

When you visit the doctor, take a car to the mechanic or attend counselling, it involves some form of diagnostic exercise. Does the doctor warm the stethoscope before applying it to your chest? Did the mechanic clean their hands before touching the upholstery? Did the counsellor find a comfortable seat for you? These issues might seem minor, but they are significant because they indicate a person’s process capability – their ability to appreciate all the factors that will affect an effective diagnostic process.

In the same way, your diagnostic process is likely to be the client’s first experience of your professional capability. You need to ensure that you have a clear map of the process. Even more important will be your capability to explain the process to the client. If your client likes to take an interest in the process then you must have a clear and concise model that will explain how you will define, gather and analyse the data.

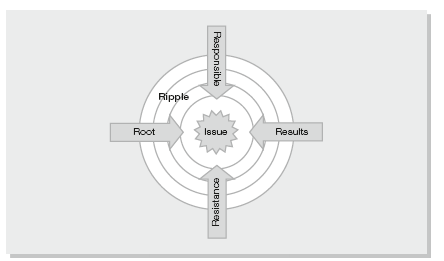

Although there are many diagnostic styles and frameworks used in the consulting cycle, they all fall within three basic actions (see Figure 5.1):

- define what data is required;

- gather the data;

- analyse the data and draw conclusions about the source of the problem.

A range of different tools and techniques has augmented these three steps, but in essence they form the backbone of a typical diagnostic project. Two additional factors that must be stressed are the need to ensure clarity about the actual issues being researched and the importance of taking a reality check to ensure that the diagnosis has not drifted off track.

Figure 5.1 Diagnostic process

Issues

As you start on the data-gathering process, it really does pay to stop, sit down and think about the issues being addressed. Once the data-collection phase begins you often find out that the world has moved on since the contract was signed. People leave, new team members join, organizations merge or split. In many cases the client who initiated the contract might no longer be around to clarify what is required. So, while the contract process within the Client stage does focus on outcomes and deliverables, it pays to spend time at this stage to confirm that the issue is still current and active.

One of the best ways to frame and clarify the issue is to ensure that it is built around a statement of ‘We can’t’, ‘We are unable to’, or ‘X isn’t doing Y’. Once this is defined then it becomes quite easy to map what data is required. We need a negative focus because a positive one can lead to misdirected outcomes. For example, saying ‘We want a new sales bonus scheme’ can lead to a range of outcomes, many of which do not address the real issue causing the problem. What we should say is ‘The present bonus scheme does not encourage a collective style of working between the account managers’. Then the options for resolution are not linked into the provision of a new bonus scheme. The statement offers the problem and goal without presenting a prescriptive outcome.

Using a negative issue statement challenges the client to question what area of the concern is being dealt with and what value will be added by any change. For example, as a consultant you will often be employed simply as an excuse to delay or defer action. The introduction of an external agent can offer convenient breathing space for the client if they are in a battle with others in the company. In forcing the research issue to be framed in this way, both you and the client will have a clear understanding of what is not happening and what information you will need to retrieve.

Data requirements

Once the issue has been clarified and a shared model is held by each member of the data-gathering team, the next step is to make sure you know what data is required. One way to do this is by breaking down the total data load into sets that define a unique package of information to be discovered. The set description will indicate the data type, source, owner, purpose, etc. Only by taking this type of structured approach can you ensure that you do not spend valuable time and money gathering redundant information. However, although this helps to clarify how the data gathering is managed, it does not resolve the issue of how to identify what data needs to be gathered.

Gathering framework

The content and context of whatever problem you are dealing with will drive the actual data sets. But in many cases it can be difficult to take the first step. Modern organizations hold millions and millions of units of data they use to run their business. Once you start to delve into the archives the amount of data will explode. Financial reports, customer complaints, supplier receipts, memos, staff surveys, etc. all come together to form this mountain of information. So in deciding where to start, the framework set out in Figure 5.2 will help to focus on what data needs to be gathered.

Figure 5.2 Data-gathering drivers

In any situation where a change has to be made, there are five sets of data that need to be understood.

- Root – is it possible to carry out an audit to identify the original source of the problem? In the case of industrial action in a small manufacturing company, it might be changes in pay rates, poor industrial relations or a change in government policy.

- Result – what is the true impact of the issue? Is it something that affects the whole organization, one particular group, or is it something that causes a problem for one product area? Whatever the breakdown, you have to collect firm and valid data that describes the impact the issue is having. The data must indicate what is really happening rather than what the client or consumer believes is happening.

- Responsible – whatever the problem, someone somewhere must have allowed it to happen. This ‘permission’ might have been given explicitly – the managing director deciding to reduce the organization’s cost base by running a re-engineering programme. Alternatively, it may have been given implicitly – a parent leaving too many sweets around the house, thus tempting a child.

- Resistance – there is often a temptation to ignore an issue in the hope that it will disappear once the problem has been resolved. However, there can be data elements within this area that might be of interest to you. Consider the resistance that might arise if a company announces plans to change its policy on using company telephones for private calls. The level of any opposition to such a change can indicate a number of important factors, such as the strength of the culture, the extent to which people are prepared to accept centralized decisions or the capability of the people to form coordinated counterattacks to any imposed change.

- Ripple effect – the first four data areas are visible and can readily be measured and mapped. But with any issue there will be an intangible radiation, or energy, emitted as change ‘ripples’ through the organization. This is the anger and emotion that surround a downsizing exercise or the excitement released by an impending global merger. This radiated energy must be understood, since it will often contain the power to amplify or attenuate the change process associated with any consultancy project.

The ease with which these five factors can be translated into data sets is shown in Figure 5.3. The example shows a consultancy project looking at the issue of falling product sales. For each of the five data drivers, a range of hard, focused and relevant data sets are shown. Each of these data sets has a purpose within the analytical framework and is seen to add value to the total picture. Although the ripple factors are perceived as ‘vague’, they can add valuable qualitative data that will help to make sense of the quantitative data emerging in the other four areas.

Figure 5.3 Data map example

Although the data you capture in these five areas might not offer the total picture, it does help to build a robust and rigorous data map that is less clouded by an intuitive and emotional decision-making process. It also offers a simple but effective tool that will help your client and the consumer to understand your data-gathering strategy. As such they will be able to look quickly at the map and point out data sets that are obsolete and other areas where data sets are needed to highlight a certain issue.

Data richness

When planning how to gather data, it can help to take a slightly different approach in setting the boundaries. Data gathering often pushes for hard, tangible and actionable facts, whereas the actual problem may lie in the soft, intangible areas of the business. If you take a clinical view of the problem, the resulting data will offer a robust story about the situation but will have little heart. If, however, it is possible to get data sets that reflect some of the softer issues, it becomes possible to enrich the picture so that it tells the real story of what is happening.

Using the model offered in Figure 5.2, far greater value could be mined by using the full depth and breadth of our capability to gather data. This gathering information can be categorized at the cognitive (head), behavioural (hands) and emotional (heart) level. Just consider the examples below and see if you have had a similar experience.

- Your son starts to keep his bedroom tidy after receiving the fifth warning that it must never happen again. Although there is a short-term change in behaviour, he soon drifts back because he does not understand the reason why a bedroom must be kept tidy and feels that it is not as important as playing with his friends (high hands, but low head and heart).

- A manager listens to a passionate call from the chairman for a reduction in costs and goes back to the office fired up to deliver an improvement. However, although he believes in the need for change, he does not really understand what can be done and what he can deliver personally. The change ends up as something that other people will have to deliver (high heart, low head and hands).

- An organization decides to put its people through customer care training. The goal is to help people to understand why customer service is important and what they can do to make a difference. People complete the course knowing the process they have to follow when dealing with a customer, but the change is short-lived and the old routines soon return because they are unable to translate what they know into what they do (high head, but low heart and hands).

For each of the five factors identified in the model in Figure 5.2, always try to gather data that represents the head, hands and heart factors. For example, if you are trying to get information about high staff turnover in a call centre, Table 5.2 identifies questions that might help to determine what data is required.

Data gathering

Once the data sets are clearly mapped, the next stage is to start the gathering process. You must determine where the data is held and how it can be accessed. This stage of the diagnostic process is well documented so what follows is a simple overview of some of the more common forms of data-gathering.

Questionnaire survey

This is one of the more common methods used to elicit data from a large population. It offers a ‘quick and dirty’ way of gathering information about the views of customers, staff, suppliers, etc. in a comparatively cost-effective manner. The basic steps are:

- decide what you need to know;

- code it into a series of questions;

- send the questionnaires to the target population;

- draw general conclusions from the questionnaires once they are returned.

The major problem with this method is the typically low rate of return. A good result will be a 50 per cent return but it can fall as low as 10 per cent. In this case it is important to ensure that a good statistical model is used to ensure that any conclusion can be generalized as representative of the entire population.

Sampling people at random is relatively simple, but it is difficult to ensure that an accurate representation is drawn from the total population. Although a true random selection might offer a fair selection, it might be that your population does not have an even distribution and there may be heavy clusters of responses from a particular area. You can deal with this possible bias by stratifying your sample. This resolves a problem where a particular tendency exists in the population, such as a localized ethnic group, focused skill set or age profile. For the sample to be representative, random samples should be taken from these particular sub-groups or strata. Another alternative is the quota sample, where the sample is based on a prescribed quota criterion. There is no pre-set makeup of the sample – the criterion is simply to gather sufficient information to meet the sample requirements. For example, the target may be to interview the first 30 people who walk into a shop.

Face-to-face interview

The face-to-face interview has the advantage that it is flexible, probing and sensitive to changing moods in the population. It allows you to get a first-hand feel for the intangible problems associated with the project. Furthermore, meeting people reduces some of the anxiety caused by your presence. The downside is that it can be prone to bias by the interviewer and it can be difficult to compile the information into a meaningful form. These problems can be partially eliminated by structuring the interview carefully. The options are a predefined question structure, limited questions and prompted responses. However, with these options you start to eliminate some of the richness associated with the approach.

Focus group

This takes the idea of the single interview and expands it to a wider group of participants. A focus group might consist of between five and 20 people, and in some cases even more. The initial benefit of this approach is that it brings disparate people together and so saves time. Another important benefit is that it offers the opportunity to extract a sense of synergistic spontaneity from the group. As people interact and share knowledge, so a vein of new knowledge can be elicited that might not have been uncovered by other methods. This data can be used as information to feed into the analysis stage or as foundation data to help construct a questionnaire.

Observing people

In some cases you might want to find out what people do rather than what they say they do. In this case it can be useful to gather data by observing people in their normal setting. This process is sometimes used in process re-engineering. Although you might gather data as to the effectiveness of a particular process, you might also choose to watch how people operate over a longer period. Often this will highlight valuable data that would have been unavailable by other means. The shortcuts that people take to save time or the way that a team interacts can only be identified by observation at close quarters.

Personal logs

Another method is to ask people to observe themselves and to record what actions they take, to whom they talk and what they think about certain issues, noting it in a personal log or diary. Although diaries are often used for social science research, they are less frequently used in consultancy. However, they are a wonderful tool for gathering specific information at local and specific levels within an organization. Diaries record both qualitative and quantitative information and can be constructed to include some pre-analysis coding. The advantage is that they show the perspective of the employees, rather than the consultants, of what is happening. They also allow the use of comparative analysis, possibly to compare how different people feel about the same issue. One final advantage is that diaries operate in the background, freeing the researcher to do other activities.

Customer database

Not all data analysis is concerned with understanding what people think, feel or do. One of the most important assets of any business is the database of financial, operational and customer information. It is also one of the most underused assets in many consultancy projects, partly because it is an erratic process fraught with bias and error. However, there are tools on the market that might help to extract some of the necessary data from company archives – these are divided into two types.

- Predictive modelling – this method is used to determine the relationship between data and the desired outcomes. The most common statistical tools used in this type of analysis include stepwise multiple regression, logistic regression, discriminant analysis and neural network modelling. These models all share the same basic idea – to predict the future, for example how customers will respond to a direct mail campaign.

- Descriptive statistics – these are used to describe and summarize what the existing data sets are indicating and what is in the database and how it is organized. Some common types of descriptive tools are frequency distributions, cross tabulations, employee age profiles, customer profiles, penetration analysis, factor analysis and cluster analysis. While this type of analysis does not predict a future event, it does describe past events very accurately.

Data validity

Although data-gathering methods differ, there are common rules that ensure that the data is of value.

- Be relevant – the process must gather knowledge about the subject area and not just cloud the issue.

- Always take the process for a test run – use a sample population from the targeted areas or use a group of volunteers. Ask them to test drive the process and take it to breaking point so that it will be robust when applied in the field.

- Trying to save money at this stage can severely limit the whole process – as the adage goes, ‘garbage in – garbage out’. If the gathering process fails to deliver data of any real value then the rest of the consultancy process will suffer.

- Market yourself in the data-gathering process – if people receive a dirty envelope with a questionnaire full of typing mistakes, they will form an immediate (poor) opinion about you and the whole process.

- When gathering the data, ensure that people are told why it is wanted and how it will be used – just because people are performing mundane jobs, it does not mean that they have mundane thoughts. Treat the data donors with the same respect you would give the client.

- Be aware of timing – the classic mistake is to come up with wonderful project plans only to find that the data research phase falls smack in the middle of August when everyone is on holiday.

- Above all else, ethics are crucial – unless people believe that their information will be held in confidence then the process and content will end up being corrupted. If the process cannot be trusted then people will only put down what they think the researchers want to hear.

The construction of the survey will often be driven by practical constraints. Although you must take an idealistic stance when you define the methodology for gathering data, at the end of the day the client’s hand is on the tiller. They will have to bear the cost so you must ensure that they are fully aware of the process being used, the associated costs and the potential benefits of each methodology. Make sure you are able to defend each strand in your diagnostic phase. Otherwise your client might start arguing for cuts, with the risk that the whole assignment is put in jeopardy because of insufficient or inaccurate data.

Data analysis

Towards the end of the diagnostic phase you will start to find yourself awash with data. This increases the chance that critical aspects may be missed through data overload. The data analysis phase needs to ensure that the data:

- has been reduced to a manageable size;

- has been synthesized to provide an indication of the root issue to be addressed;

- is prepared in a form that will help to develop a compelling argument for action.

The two views that drive the analysis phases, the outside-in (predetermined analytical model) or the inside-out (emergent analytical model), were described earlier. In the first, you use a degree of scientific rigour to analyse the data and understand how it matches the initial proposition. In the second approach an inductive framework is used, where you draw on some form of emergent cognitive framework to tease out patterns and themes in the data.

Outside-in

With this method, your task is to take the data and find out if it proves or disproves the hypothesis offered at the outset of the diagnostic phase. This is a relatively simple process and can be facilitated by the use of a comparative matrix.

Table 5.3 offers an example of such a process. For example, you might have identified three core propositions that you believe are true. These propositions are then tested against the data collected during the research phase. The result is a number of summary statements, each indicating how the data stands up against the core propositions. Your first proposition may be that senior managers must actively support the change for the transition to be effective. However, data from the morale survey suggests there are doubts about trusting the senior team. The implication is that even if the senior team offers support for the change, staff might not believe it. This offers both evidence that a problem might exist and a compelling argument that the senior team needs to take immediate action.

As an analytical tool, this method is powerful, simple and cost-effective. However, the downside is that it limits your level of flexibility. Since the whole emphasis is on the original hypothesis, this limits the opportunity to pick up on some of the more spurious or complex indicators. At the end of the day, you are simply getting an answer to the question posed at the outset of the diagnosis phase. However, you are unable to say confidently that the questions were relevant and correct.

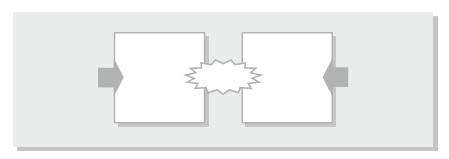

Inside-out

Rather than using a fixed argument at the outset, this approach uses an emergent model where the continuous analysis of the data will drive the questions and processes used. This is often driven by a desire to discover how things ‘are’ within an organization or to come up with an innovative solution that has not been tried before. This search for innovative and creative solutions means that you will be breaking new ground every time the process is used.

The outside-in model is like building a house according to a prescribed architect’s design; the inside-out approach, on the other hand, is like building a house according to the materials available (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Inside-out data analysis

Source check

One of the biggest mistakes people make in data-collection is to draw conclusions regarding the source or root of the problem, only to forget the original issue under investigation. The danger is that after weeks or months of frantic data-gathering, followed by torturous days of data reduction, the consulting team finally let out a eureka scream, and bring forth their view of the source issue that needs to be addressed. However, in this euphoric moment no one thinks to go back to the source problem, undertake a reality check and ensure that a resolution of the problem identified by the data analysis would actually address the issue first raised by the client.

For example, a consultancy team is investigating why sales are falling on a particular product line. After weeks of data-gathering, it comes to the conclusion that the problem lies in the method used to manage the sales team’s bonuses. Although this diagnosis is sound on a superficial level, before the team progresses to the Create stage of the consultancy model, it would pay to undertake a ‘quick and dirty’ reality check. Only when it checks with the original problem raised by the client does it realize that the bonus scheme operates across all product lines but the problem exists only in one area. This indicates that the problem cannot lie solely with the bonus and that a more localized problem must be at work.

The tendency to drift in the diagnosis stage is a common occurrence. After labouring away at the data definition, gathering and analysis, it is easy to lose sight of your goal and slowly slip into another frame of reference.

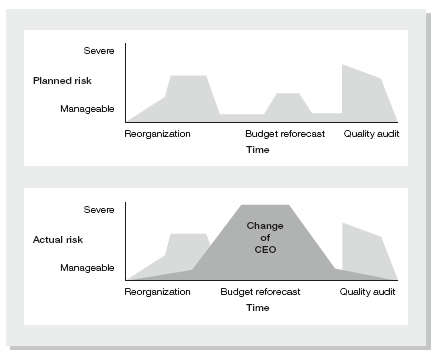

Phase mapping

An important point to consider in the Clarify stage is how the different components within the system relate to each other. Most engagements act on sub-systems of other systems, such as teams within a unit, a unit within a division, a division within a business and so on. As such there will always be external factors that can suddenly affect the engagement. These might include inward investment, changing personnel policies, corporate expansion schemes, downsizing, etc.

Imagine a product development team that needs to recruit new people to complete a market review. Unfortunately, the division within which it sits has budget constraints from head office resulting in headcount restrictions. Additionally, at a group level, there may be plans for downsizing. The decisions taken at each level make sense in isolation, but when taken as a whole result in discontinuities across the organization.

It can help to view these variations at each level as waveforms with differing amplitudes and frequency. There will be times when the waves complement each other and times when they are in conflict. You need to be able to map these energy waves and determine if the change is timely, taking into account any wave conflicts. For example, at times investment will be green-flagged and capital will be readily available. At other times capital might be rationed and teams will struggle to fund their projects. Given the complex structures that exist in many organizations, this change in state will not always be common or clear to everyone. Thus different levels of the organization will have opposite views as to the availability of capital.

In Figure 5.5 the consulting window suggests that the team is about to progress with a capital investment programme that is tacitly supported at divisional level. However, once the business case reaches organization level it is likely to be rescinded because the organization is on a downward cycle. Although the organization has advance knowledge of the impending scarcity of capital at an industry level, this is invisible to the team.

Figure 5.5 Organizational waveforms

The danger is that if you are unaware of this phase misalignment, then time and money can be spent developing a proposal that is rejected once it reaches another part of the system. Although the investment project might make sense to the team based on its local view of the world, if it is unable to appreciate how the world looks to the other systems then it will be frustrated in its change process.

One way to avoid this trap is by networking. If you consider the client system in isolation there is a risk that phase problems will occur. Obviously you must focus on your project area but it is also important to cultivate relationships across other systems within the organization, both vertically and laterally. Only by creating a network of ‘informants’ will you be able to understand the total picture. For example, a police detective will not focus on the criminal in isolation. Shrewd detectives will draw on an entire network of informants and contacts to understand what is happening in other parts of the criminal world. By doing this, they are able to manage both the immediate crime investigation and the bigger picture.

Once you have a clear view of the problem, the nature of the change and the viability for success, you must identify those people with power over any proposed changes. Although your client is often the person that has the power to make decisions on the progress of the project, in the majority of cases many of the real decision makers only come out of the woodwork once the project has progressed beyond the contracting stage.

Shadow dancing

Whenever the client and consultant come together, there are two sides to the association:

- surface issues – these are things that both are happy to share;

- shadow issues – these are the hidden behaviours, thoughts and feelings that they are less comfortable about sharing.

Shadow issues are important because they often drive the force and direction of any change. You probably know people who are scared of spiders or have a particular aversion to a type of food. Although these fears are seemingly silly, they can significantly influence the decisions people make and how they manage their lives.

In organizations, the shadow factors might be all the important information that does not get identified, discussed and managed in the open. The shadow side deals with the covert, the undiscussed, the undiscussable and the unmentionable (Egan, 1994). These sit in the shade of the person and only appear when a light is deliberately shone on them (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 Surface-shadow split

We might see this with the smile of a clown. The public sees the fool who entertains the children. But the smiling face often conceals a sadder person on the inside. They might see themselves as old and weary and not having achieved the goal of running their own circus. Finally, who are they really? Do they know what is deep inside and are they prepared to share that with others?

Although you might be fortunate enough to know your client well, in the early stage of the engagement you are unlikely to be emotionally connected with them. This can be like the first fumbling teenage date, where both kids are trying to second guess and satisfy the goals of the other without compromising their personal values and integrity. In the same way, the early meetings with a client can end up as a series of fumbling encounters, where both people are trying to understand the needs and goals of the other. Part of the reason why this dilemma occurs is because we all operate on these two levels of interaction, the surface and the shadow. The surface issues are considered on an open and level playing field, and the shadow issues are the factors that both sides choose to hide from each other.

In a typical consulting project you might offer what appears to be a practical and sensible change proposition, which the client may rebuff with arguments and concerns about its feasibility. But are these rebuttals coming from the reasoned head of the client or are shadow concerns forcing unrelated and often irrelevant issues to the surface? For example, a re-engineering proposal has been turned down because it involves head office relocation. On the surface the proposal offers a number of financial and operational improvements for the client. However, the unseen shadow implication is that the client’s children’s education will be interrupted and their partner’s work and social life hampered. This type of personal prejudice can swing the balance against a rational solution, thus destroying (for an unknown, or at least unstated, reason) your proposal.

Crucially, when developing a relationship with the client you must listen to what they say and, more importantly, watch what they do. The pained facial expression as your client talks about the business goals or the involuntary eye movement as the topic of relocation emerges are valuable indicators that highlight a shadow problem. They will not automatically tell you about the deeper issues at play but they certainly offer signals that the topic could be explored further to pull out any shadow factors.

Argyris (1992) suggests that there is a fundamental set of behavioural rules that drives shadow behaviour and they cross all nations and cultures. People keep these rules in their heads to help them to deal with embarrassment or threat:

- bypass embarrassment or threat whenever possible;

- act as if you are not bypassing them;

- do not discuss this bypassing while it is happening;

- do not discuss the undiscussability of the undiscussable.

In tacitly following these four rules, people will inherently lock themselves into a ‘I know it’s true because I say so’ style of behaviour. The problem surfaces when you attempt to tackle any of these four rules head-on – asking people to clarify what the problem is and trying to discuss some of the deeper issues as part of the diagnosis process. All of these are likely to trigger some form of defensive reaction that in turn drives up the shadows.

Suspicion often surrounds the diagnostic stage. People are likely to ignore anyone who tries to delve deeply into the shadows. You must be able to mentally climb inside the person under investigation, to take on board their beliefs and goals and feel what they are feeling, no matter how alien or bizarre it might seem. By doing this, it becomes possible to understand what their personal needs are and why they are operating from the shadow side of their personality. To do this it helps to map the nature of the shadows that both you and the client have.

Shadow map

The shadow map is a simple tool that allows you to understand what shadows might reside in you and the client (or consumer) and then determine how to take remedial action to bring to the surface the factors that need to be addressed.

In Figure 5.7 the consultant must be able to reflect on any shadow issues that you have in relation to the client and the project. At a surface level you might be prepared to talk about the project plan, fees, your skills set and other clients with whom you have worked on similar projects. However, shadows for the consultant might be the fact that the project was sold because of pressure from the senior partner to drive up revenue, a concern that the technology is not proven, and maybe that you have contracted to deliver another project at the same time and so will need to split your time across two key clients.

Figure 5.7 Consultant shadow map

In Figure 5.8 the client’s surface issues may be the company strategy and business processes, the current budget and the personal goals that are associated with the success of the project. The client’s shadow issues might be the fact that they know the budget will be cut in the near future, that the project has been tried a number of times before and failed, and that the managing director sees the change as very low on the list of business priorities.

Figure 5.8 Client shadow map

Once the consultant and client come together then we end up with a combination of four constructs (see Figure 5.9) – the things neither wants to discuss; the things the client will discuss and the consultant will not; the things the consultant will discuss and the client will not; and the things that both will happily discuss. The resulting four segments are not fixed elements, since they change in size depending on the level of disclosure and willingness to share undiscussables by the client and consultant. As both players flex their degree of discussables, so the shape of the shadow map will vary.

Figure 5.9 Consultant and client shadow map

When the shadow map is like Figure 5.10 both client and consultant are open in their interaction. The surface area offers plenty of space for both to share the discussable items and so effect a robust clarification stage. The one risk with this shape is being lulled into a false sense of security. It is like the married couple who proudly proclaim their openness to the world, only to find out that one of them has a deep secret that blows the whole relationship apart. Although the bottom-left box is only small, it can contain dangerous viral spores that can kill a relationship.

Figure 5.10 Open interaction

In Figure 5.11 the client is happy to disclose and share many things but the consultant is closing down and is not happy to share what they are thinking and feeling. The first question to ask is why – what is causing them to hold back and create undiscussables in the relationship? Second, what does this large shadow box contain and are there elements in there that can be destructive for the engagement?

Figure 5.11 Consultant withdrawal

Figure 5.12 is the killer shape. Both the client and consultant are limiting their level of disclosure. Now, if this is the start of the relationship then it is a shape that might be expected and possibly makes sense because both sides might have commercial sensitivities to protect. However, if this shape exists part-way through the engagement then it is a dangerous sign because neither party is prepared to open up and share their thoughts and feelings. An example of this shape can be found in large bureaucratic companies that are near to shut-down as all the players in the internal market fight to protect their patch and cover their backs. It is also a style of day-to-day management that can still be found in certain companies.

Figure 5.12 Limited interaction

Effective clarification can only really take place when the (necessary) shadow has been brought to the surface and you are free to understand what is going on. The art of shadow dancing comes in your ability to move two key lines within the shadow map, as shown in Figure 5.13. Although there will always be a variety of strategies that can be used to open up the surface area and shrink the shadow area, they will be primarily dependent on the ability to move the two lines in the direction shown by the arrows. The consultant must be able to move their line from top to bottom to make more things discussable, and the client must be helped to move the line from right to left and do the same.

A caution with this model – your goal is to attain the necessary information to facilitate the clarification of the problem or issue being raised by the client. The key word is ‘necessary’. The danger in surfacing shadows is that all of a sudden you are faced with the undiscussable that you don’t want to deal with and that has little to do with the project on which you are working. This is a real danger no matter what the change being managed. For example, when analysing processes in readiness for a new computer system, the analysts might uncover deep organizational rifts between departments that lead to the axing of a senior manager; the quality auditor may surface the fact that faulty items are actually being sold on the sly by local managers; penetrating questions by the independent financial adviser may uncover deep rifts in a marriage that trigger a divorce.

Figure 5.13 Redrawing the shadow map

Very few consultants or coaches are trained to deal with deep cognitive, emotional or behavioural problems that may surface when they try to clarify a client’s needs. It is therefore vital that if faced with a situation that you are not equipped to deal with, you act responsibly and advise the client to seek appropriate professional help. Unless you are trained, however well-intentioned your actions, you may well do more harm than good. In some circumstances it can pay to agree this with the client when agreeing a contract for the engagement.

Sabotage secrets

Beware also of the sabotage factors that have the potential to destroy a relationship and client engagement. The sabotage secrets are those shadow factors that sit deep in the bottom left-hand corner of the shadow map (see Figure 5.14).

The problem with sabotage secrets is that they are buried so deep that neither the client nor consultant really wants them to be surfaced. This might be the case on the morning after the office Christmas party. When people walk into the room in the morning, a certain number of people probably know that something awful happened and that they were part of the awfulness. However, they choose to stick with the maxim of ‘Let sleeping dogs lie’. All will be fine so long as the dog stays asleep and does not get woken. The problem comes when the deep shadow issue finally does get surfaced – maybe by someone inadvertently sharing some photos from the party. Then it becomes destructive and sabotages the office relationships that had managed to tick along nicely in blind ignorance.

Figure 5.14 Sabotage secrets

People often believe that by keeping these potentially destructive acts at a deep shadow level they can be forgotten. Unfortunately, too often there will be leakage. This leakage might be nervousness when close to certain people, potential panic when dealing with certain information and the constant fear of disclosure that leads to sleepless nights. The paradox is that although the secrets can be destructive when hidden, the process of bringing them to the surface can also be destructive. There is no right answer – the trick is to be aware that secrets can exist for many people and organizations and to be prepared to deal with them if you believe that they are causing a potential problem.

Surfacing strategies

If you really want the client relationship to be open and free of destructive shadows then you will need to develop strategies that will allow you to unearth and expose areas of potential liability. Although the emotional act of making the undiscussable discussable can be difficult, there are simple strategies that you can employ to help manage this process.

- Disclosure – this is possibly one of the most powerful and effective ways to open up the shadow area. If you are with someone who really does not want to open up (and we all generally know this when it is happening to us), be brave and open up to them. Find things that maybe you were not going to share with them and explain that it is quite a deep feeling but that you want to share it with them so as to help the relationship develop. The upside is that by sharing this and demonstrating that you trust them, they might reciprocate and begin to open up. The downside is that they may simply soak up all your shadow information and give nothing back. Only you can decide how far to go with this, but if you feel that nothing is being reciprocated then in many cases it might be prudent to pull back for a while and try an alternative strategy.

- Deflection – this is a displacement process that is often used in marketing. Imagine you are walking down the street and a market researcher inquires if they can ask some questions. They want to test out a new perfume to see if people believe it will make them smell sexier. Now if someone sprays this on you and asks ‘Do you feel sexier?’ – the chances are that it can be really awkward to answer truthfully because you feel embarrassed. However, if the researcher lets you smell the perfume and then shows you a picture of a woman who is wearing the scent, you are more likely to answer the question, ‘Do you think that this scent will make her smell sexier?’ This is because the focus of attention has been displaced. It has created a safe haven where you feel that you can answer truthfully without being embarrassed. In the same way, if you are with someone who is showing signs of having shadows then talk about another friend of yours that has a problem they will not share with anyone. Talk about this and say that you really want to help this person but are not sure of the best way to do it. Alternatively, maybe talk about a TV show or film that you saw recently where the characters caused all kinds of problems for themselves simply because they did not open up when it was important to do so. By making the shadows discussable you may create a safe house for your friend to start to surface some of their issues.

- Direct – if your relationship is strong enough then sometimes you just have to tell it as you see it. Maybe there is no time to pussyfoot around, or someone else is being hurt or damaged because of the shadow games, so you just have to go for it. A friend of mine had a drink problem and we both spent years avoiding the issue and just finding ways not to talk about it, until one day I just surfaced the issue and said how I felt. It did not resolve the issue directly, but it has certainly put it on the table so that we can now raise it again without having to play too many games.

- Drink – liberal amounts of alcohol certainly break down barriers – it happens every night in most city centres after work. However, the downside is obviously that maybe too many shadows can surface, which leads to even more shadows the following morning when you meet the person and realize that you said things that should not have been said – or even worse you passed other people’s private shadows that were shared with you in confidence. In summary, big gain – but big risk.

- Diversion – sometimes it helps to talk about something that takes the other person’s mind off the shadow area. Once the rapport is developed you can gently ease back into the area without appearing confrontational. This way the bond and trust is put in place to ensure that when the shadows are surfaced the other person will not feel too uncomfortable.

- Delay – some issues are best not dealt with there and then. Just wait and bide your time until a convenient moment surfaces when it is appropriate. However, be clear that this is a conscious strategy and not a natural tendency to avoid talking about something that may provoke an emotional response from the other person.

With all surfacing strategies, the objective is to create an emotional connection that will in turn allow you to clarify what is really going on. The danger with these strategies is that they can be viewed and used as manipulative tools. This is a dangerous game to play and one that is diametrically opposite to the shared success outlined in the Client stage. My advice is to use these strategies if they help to build effective relationships, but always be open about the use of the strategy and never try to use it in a covert or duplicitous way.

When using the shadow map there are a number of rules of thumb that are useful to remember:

- Shadow dancing – we often expend more energy avoiding the shadow issues than we do dealing with them. Sometimes it is better in the long run to stop dancing and start delving into the undiscussable areas.

- Shadow management takes courage – in the same way that it is difficult to go home and talk about the unspoken problems that have been dogging you for the past week, surfacing shadow issues with a client or consumer takes immense courage. Never underestimate just how hard it is going to be to dive into the shadow area and how painful it can be once the issues are out in the open.

- Pandora’s box – there are always shadow factors that you need to know about because they impact on your change programme. However, there will always be shadow factors that have no bearing whatsoever on your programme and surfacing them may cause you a problem.

- Professional–personal switch – the danger is that once you have entered the shadow arena the client regards you as their friend. At this point all their problems might start to surface. In this situation you might take that difficult step from a professional relationship to a personal one. Once in this area it can be difficult to move back into the professional one. The consequence is that you gain a new friend but lose a client.

- Terms of trade – often, shadows are managed by trading. Being prepared to advocate and expose a shadow area or secret that you have in the hope that the client will be prepared to expose one of their secrets. You need to understand the trading process and decide how much you are prepared to trade away before pulling up the protective drawbridge.

- Complex shadows grids – don’t forget that you will always have a myriad of shadow grids in operation with your client, the various consumers, different stakeholders and even with your family after you have spent the third week away from home.

Culture

When clarifying how change is undertaken, the culture of an organization needs to be understood. Culture can stall and kill a project with hardly the blink of an eye. All the professional and passionate planning initiated by a consultant will be ruined if the change and outcomes do not align with the culture. You must clarify three things:

- What is the cultural make-up of the target audience?

- What personal cultural bias do you have?

- What is the degree of cultural diversity across the group?

Culture audit

A culture audit is designed to give a clearer view of the culture with which you are dealing. This knowledge is used to aid the diagnostics process, to ensure that an appropriate change methodology is applied and to test the viability of any solutions. This is clearly an art as opposed to a science. An organization’s culture is simply an approximate description of the preferred style that the people choose to use. As you deconstruct the organization, so the approximation becomes less accurate because individual personalities and tendencies will emerge. At best, the outcome of any audit must be treated with some scepticism, and at worst treated on a par with horoscopes. However, generally, it is possible to get a feel for a culture even if it cannot be specifically calibrated. A simple test is to walk into the foyers of three different hotels. There is every chance that within a few minutes you will have an intuitive grasp of the culture of the organization. You will be able to guess what is acceptable to the staff, who wields the power and the extent to which the hotel has verve and energy. Although you would not invest your money on the strength of this, it can offer enough data on which to make a number of broad suppositions about an organization’s operating style.

It can help to think of an organization as an empty canvas that has been painted with a varied mix of paints and colours. Like the artist who slowly builds up a picture, often not knowing quite how it will end up, so as an organization grows it adopts a range of different cultural attributes. When investigating the make-up of the picture, the consultant’s role is to deconstruct the colour base and understand how the way the colours have been mixed contributes to the end picture. Just consider what a varied mix of pictures an artist can create from a simple range of colours. In the same way, although each organization will be unique, they are essentially made up from the same set of cultural attributes.

- Artefacts – can include tools for company rituals, common business definitions, reward systems, logos and office design.

- Beliefs – what does the organization value and regard as being important? This is seen in the moral and ethical codes offered by the business. The difficulty is that beliefs are deeply personal things, so trying to define them at a global level will lead to averaging or levelling and some degree of compromise.

- Control – is power based around the structure of the organization or the capability of the individual? To what extent does this leverage affect political action?

- Discourse – what is the balance between the open and hidden elements within the business? To what extent will people open up and talk about issues in a shared environment and to what extent are issues held for debate in private, closed and secure groups? This gap between the open and hidden levels of discourse can be used to understand the difference between the espoused and actual cultural factors.

- Energy – where is the energy expended? Is it on issues that are concerned with internal processes or is it externally orientated, where the primary focus is on the customers, suppliers and stakeholders?

- Flow – how do people move in, out and within the organization? What is the accepted staff turnover rate, what is the balance between formal and informal recruitment processes and why do people leave the business?

- Generative – to what extent does the organization understand and drive its capability to innovate and learn? Do individuals feel that they are empowered to develop themselves? To what extent is knowledge shared between individuals and what infrastructure exists to facilitate the sharing of knowledge?

One danger with this type of culture model is that it might be viewed as a prescriptive paradigm. Yet culture is dynamic and unpredictable, so dissecting an organization at any time, region or level will produce a range of ideas and themes, some of which align while others conflict. Any culture analysis can offer only a subjective snapshot and should never be treated as the definitive model of an organization’s style of interaction. However, the purpose of the analysis is not only to understand the culture but to also develop a multi-perspective map and to understand how the culture is perceived by the various elements within a business.

Table 5.4 shows how the culture model can be mapped against the hierarchical levels within an organization. In this case, the matrix might highlight potential issues.

- Is there culture blindness between the various layers within the business? Does one layer believe that certain behaviours are natural while another group feels that an alternative set of norms is in place? One example might be that the directors and senior managers believe that learning is encouraged at all levels, while line managers and process operators feel they do not get the opportunity to develop their competencies.

- Is there is a cultural paradox? For example, directors might advocate cross-team migration to encourage knowledge flow across the business. However, from a control perspective, the directors still operate a highly centralized system where all internal transfers must be signed off at senior management level. This creates a ‘gate’ that inhibits internal movement because people are wary of requesting a transfer in case their current manager sees it as a reflection on their ability to retain staff.

Trying to gather information on culture is difficult because it is intangible and subjective. If the goal is to gather descriptive information then that is relatively easy. All the respondent needs to do is outline the world as they see it. You can then undertake a comparative analysis to identify potential mismatches or inconsistencies. However, it becomes harder if you are trying to encourage participants to offer an evaluative comment on the culture. It will be difficult for people to say if anything is good or bad because the response will be biased by the culture in which they exist. And they will often be the least able to diagnose the culture in which they operate. It may be possible to draw objective data from a subjective position through comparative measures. For example, it is difficult to ask someone to describe a sound or a picture, but asking them to describe it in relation to another sound or colour will make life easier.

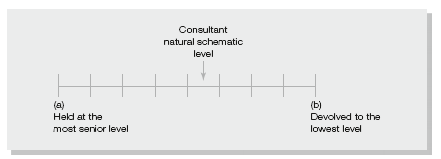

Personal bias

As part of any diagnosis process, it is important to map your own cultural bias. All people have schema, or maps, that drive both the thoughts they have and the actions they take. To understand this you might try to calibrate your own cultural schema. You do this by calibrating your schematic view against a range of alternative views. For example, you might ask yourself the question: ‘When are organizations most effective?’ Choose an answer from (a) when financial control is held at the most senior level; (b) when financial control is devolved to the lowest level.

Once your cultural bias has been mapped (see Figure 5.15) then you can take it into account when developing the client’s map. For example, if you naturally orientated towards the individualistic style of control then some organizations might appear to be excessively autocratic, and vice versa. This can never be calibrated in a truly scientific way since it is built on a subjective precept. However, if you have a clear view of your own schematic map then it can help to temper how your opinions are formed about the client organization.

Figure 5.15 Personal bias indicator

Cultural diversity

In any change process, the level of cultural diversity within an organization will be significant. What seems natural to a white Anglo-Saxon male might appear as rude to an Asian female; what might appear to be a natural action for a Japanese businessman might feel uncomfortable to an American. Cultural diversity is an everyday issue since cultural differences are found in coffee rooms around the world. Whereas culture was once broken simply into blue- and white-collar, now no two cultures will be the same because all organizations are made up from a complex mix of people from different backgrounds. This can emerge as a significant problem when companies try to effect large-scale change. Consider the following example of problems associated with a global merger:

A potentially damaging clash of cultures is brewing among executives at the newly merged oil giant BP Amoco just a month after the deal was approved. British executives fear their new US counterparts do not share their concern about corporate expenses, according to a senior source at the conglomerate. Attention has focused on the retention of a corporate jet by the American chairman, the costs of last month’s board meeting in London, and the use of Concorde by US executives. There is increasing irritation at every level in the company and a feeling that this is totally inconsistent with the culture of BP. (Cracknell, 1999)

Cultural diversity can cause major problems within a company that has an inherent and embedded dislike for change and variety. However, an organization that welcomes the richness of diversity can build on this variety to enhance its ability to sell and operate in diverse global markets.

Your challenge is first to understand the make-up of the cultural mix within the client organization and second to manage the engagement within this bias. There are two main areas to consider – the intra- and inter-cultural factors.

- Intra-cultural mix – this is where an organization is constructed using people from different geographical, religious or ethnic backgrounds. As this internal mix changes, so the overt and covert rules that drive and underpin the organization are constantly being challenged, sometimes in horrific ways. Consider the case of the US oil company that set up a drilling operation on an island in the Pacific using local labour. Within a week all the foremen were found lined up on the floor with their throats cut. It turned out that hiring younger people as foremen to supervise older workers was not acceptable in a society where age indicated status (The Economist, 1984). The absorption of people from different cultural backgrounds is fraught with problems and you must be alert to two things – the mix ratio and the extent to which the diversity is openly accepted. If the mix ratio is one where there is a predominance of one cultural group with the others in the minority then there are issues held in check by the majority group. This leads to the second point, the extent to which the diversity of cultural drivers is discussable within the business. Is it OK to talk about the different cultural beliefs and ideas or are they repressed by the dominant cultural force? Unless you are able to map and manage the intra-cultural dynamics, there is a risk that they will be wasting both your and your client’s time and money.