Stage seven: Close

This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end;but it is perhaps the end of the beginning.

Winston Churchill

The contract is over, it is time to say goodbye and move on. But like watching a good play or tasting a fine wine, it is that last memory that will remain and that may cloud the recollection of the total experience. This ‘recency’ factor means that the last items presented are more likely to be recalled than those that went earlier. Therefore it is important for you to manage the exit carefully and not just assume that it will be OK to ask for the money and leave.

Failure to stage-manage the closure process has led, and will continue to lead, to many disasters.

- Consultants were convinced that now the project action had been completed, no formal review was necessary with the client. Although they were paid, no further contracts were offered because the client felt that the consultants had not been prepared to listen to the client’s view of the outcomes.

- Although the board was happy with the new processes that consultants had helped to deliver, it was starting to question the real value of the change. It believed that it could have made the change itself, and so could have saved a substantial amount of money. The problem was that the consultants focused on telling the board what had been delivered. If they had communicated how the company had changed as a result, the board might have understood that there were elements that it could not have delivered itself.

- The consultants had finished a great piece of work and the client and consumer were happy and keen to build on the work. However, the consultants were relatively new to the consulting world and felt that they should not be trying to sell on the back of success. They believed that if the client had wanted further work done they would have indicated that as part of the relationship. The end result was that both parties split with an unspoken resolve not to work together again and hence there was a lost opportunity.

- The consultants closed the project down and left to work on another project. But many parts of the client’s organization had built a close working relationship with the consultants and tended to call on them for advice on many of the core issues within the project. Their departure meant that people felt slightly let down and were not keen to make use of their services again.

So, when closing an engagement you must avoid the entirely natural urge to say goodbye with a cheery wave on the assumption that everything will be all right because the project outcomes have been achieved. There are many tangible and intangible issues that need to be addressed at this stage, and you must work with the client to ensure that time is made available for the closure process.

Within this stage of the Seven Cs cycle, the following issues need to be considered.

- Look back and learn – encourage your client to consider what has been learned over and above the planned outcomes of the change.

- Look to let go – the onus is on you to ensure that at the point of departure all unnecessary levels of dependence have gone from all sides of the relationship. The key question is can they fly solo?

- Look at the value – it is important to understand how the outcomes from the change have tangibly delivered improvement to the operational or commercial viability of the organization.

- Look forward – on the assumption that the consultancy assignment has been handled professionally and has delivered the appropriate outcomes, then it may be appropriate to investigate what opportunities might exist for further work.

- Time to say goodbye . . . – with all great relationships, letting go can be hard. But if we don’t then we become responsible for the creation of a dependent relationship which may give short-term gain – but will generally lead to longer-term problems.

Look back and learn

The consultant is responsible for ensuring not just that the job is done, but also for helping the client group understand how it was done, why it worked and how the client can repeat a similar exercise by flying solo. A key component in the Close stage is the ability to learn and reflect on what actually happened rather than what people think happened in the project.

The after-action review (AAR) is a powerful tool that can assist in managing this process. It does this by eliciting feedback under a relatively controlled process. Typically, all the key participants who supported the engagement or operation will take time out to examine – in a non-incriminating manner and with the objective of organizational learning – how the project was managed. Their aim is to identify learning points and suggest ways that the next cycle can be improved.

The whole AAR process is designed to be simple so that it can be easily used in any situation. It follows a set of five primary questions.

- What did we expect to happen?

- What was the objective of the piece of work?

- Did we have a clear outcome?

- Were the players involved clear about the change?

- Were the measures communicated and understood?

- What are the different perceptions from each member of the review?

- What actually happened?

- What was the outcome?

- How do we know?

- What does each person perceive to be the outcome and what are the perception gaps?

- What explicit evidence do we have?

- What anecdotal or intangible evidence do we have?

- What worked and what did not work?

- Was there any gap between what we expected to happen and what actually happened?

- How would we rate the outcome against our expectations, the client’s expectations and the consumer’s expectations?

- What helped the good to be good?

- What caused the bad to be bad?

- What helped the success or caused the failure?

- What alternative courses of actions might have been more effective?

- What have we learned?

- What should we take forward to use next time?

The AAR creates a safe container, where people are able to express freely what they perceived to have happened without fear of recrimination. Although it would be foolish to think that this can always be guaranteed – because people are people – the use of a formal agenda and structure with defined ground rules about behaviour and desired outcomes can go a long way towards facilitating an open learning process. The key factor is that it should always deal with the process and not the people. If the review begins to focus on ‘who’ rather than ‘what’ then it is heading down a spiral of recrimination and blame that will kill any chance of real tangible learning.

The primary benefits of any effective AAR will be that it:

- creates a temporary pause where people can take a breath;

- allows the client to test intended outcomes against actual outcomes;

- allows for triangulation of data – pulling together different sources into a single document;

- identifies what to keep, what to let go and what to amplify next time round;

- links the three threads of operational, tactical and strategic change under a single review process;

- captures and communicates learning based on fact rather than fantasy;

- allows for immediate fixes rather than waiting for lessons to go round the bureaucratic structure;

- signals a deep desire on the part of the change team to learn.

The US Army has been using this process as a way of managing learning after missions. The Army began the AAR process in the 1980s and has been refining it over the years. It was first used shortly after the Vietnam war, in the Mojave Desert, where 8000 US soldiers were conducting battle training, and it has been suggested that much of the US Army’s success in the Gulf war came from its use (Financial Executives International, 2002). For many consultants, the process of engaging a client group will be very similar to an army mission, so the AAR is a powerful tool that can help the consultant to take learning into new client engagements and help the client to bring learning back into the business for free.

Look to let go

All through the life of the change process, the drivers tend to be based around growing the relationship – improving the association so that the consultant develops a high degree of trust and responsiveness with the client. However, as this relationship grows, so the level of dependence grows between the various players. The problem is that at the end of the day both you and the client have to let go and break away from the relationship. The onus is on you to ensure that at the point of departure all unnecessary levels of dependence have gone from the relationship, because ‘to have a situation where there is chronic dependence on consultants is an implicit admission of ineptitude in management’ (O’Shea and Madigan, 1997).

At the start of the relationship you are often seen as ‘the expert’, someone who has all the right answers and will be able to solve the problems. While this can help to ensure that buy-in takes place, the danger is that a dependent relationship is formed – one in which the client is sometimes unwilling to let go of your perceived expertise. This can be seen in the patient who will only go to see one particular dentist or the preference that you might have for a particular car mechanic. However, a problem can arise when the dentist or mechanic decides to move. You are left high and dry, without anywhere to turn when the next problem surfaces. Thus there is a difficult balance in any client relationship – you must be close enough to develop a trust-based association, but distant enough to allow independence and freedom.

A common pattern in consulting projects is shown in Figure 10.1. The first stage is where you meet the client. There is still a freedom of choice about the relationship, like a couple out on a first date sizing each other up. Once there is an agreement that a relationship will be formed, you will typically have quite a high level of dependency on the client. You will need help in understanding the working of the system (at the Clarify stage), access to the right people and confirmation that the initial work seems to be effective. However, once the process goes into the Create and Change stages, there is a shared dependency – both parties have invested time and reputation in the relationship and cannot afford to see it fail. Beyond this, in the Confirm and Continue stages, you are probably coasting and might well be starting to think about the next project. However, the client now has a strong dependency on you to prove that the outcome is as agreed, otherwise it might reflect poorly on them. In the final Close stage both you and the client should be back at the start of the loop, able to reflect on the relationship in the cold light of day. It is from this rational position that any decision is made to pursue further options for working together.

Figure 10.1 Dependency loop

Problems can arise if you try to close the relationship while the client is still dependent on you. Change projects often fail because the consultant has gone and the client and the consumer are left high and dry without the real confidence or ability to run with the change. As a result, one of several things can happen:

- the client’s organization reverts back to the state that existed before the change;

- the client re-employs the consultant to return and fix some of the problems again;

- the client turns against the consultant and employs a different firm to fix the problems.

Whichever option is followed, the end result is unsatisfactory and one that you should try to avoid. Dependence is a positive state only when both parties are aware of the condition. If one or both groups is unaware of the reliance then this can only lead to an unhealthy situation. Your goal is to develop a relationship that is based on a spirit of mutual interdependence.

Look at the value

The bottom line for any change must be to add value to the system being changed. This might be through modifications to people’s behavioural routines, the implementation of a new information system, or the completion of a strategy to meet an international standard. If the core value cannot be extracted from the outcome then it becomes difficult for the management team to justify the time and expense of the change to the stakeholders of the business. In the closure stage, you must ensure that the added value is clearly understood by and communicated to the client and the end consumer. The notion of recency is paramount at this stage, because their lasting memory of you and the consulting engagement will be heavily influenced by the final messages and signals that you send out. Hence, you must ensure that the message of positive added value is included in all interactions with the client (Lascelles and Peacock, 1996). It is important that you present your role in developing this added value in as simple a form as possible. Developing grand outcome statements or strategic presentations is useful for those people who have been involved in the change, but will mean little to those in other parts of the organization. It is essential that you leave the client with a simple message that can be readily shared across the organization.

There are two aspects to the value management process.

- Value management – identifying the area of the business value improvement that has been managed.

- Value differentiation – counteracting the impact of value shift in the mind of the client and consumer.

Value management

Value management is about the ability to understand clearly and communicate where value is being created. Value in this sense is a tangible function – something from which the client will receive benefit, be it commercially, emotionally or physically. Nagle and Holden (1995) define it as the total savings or satisfaction that the customer receives from the product – economists refer to this as the use value or utility gained from a product. In consulting terms, it might be defined as the benefit or gain that the client receives following the change engagement. Although your contract will clearly indicate the change that must be made to satisfy the commercial or social relationship, it might not include a specific focus on the value that will accrue on conclusion of the change.

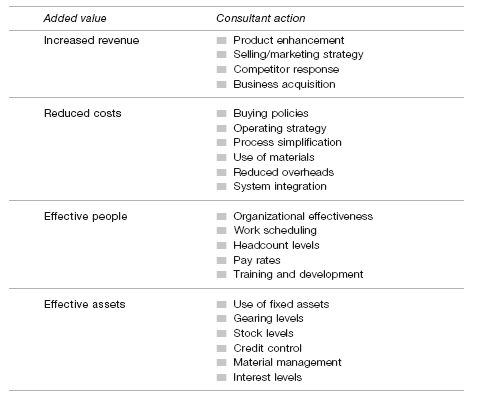

Although there will be commercial consulting engagements that fall outside this definition, the vast majority of programmes will realize value from the change. As an example, typical consulting actions have been listed in Table 10.1. By allocating actions to simple headings it allows a consistent message to be communicated to the client and consumers. Although your engagement might be highly complicated and detailed, unless you are able to offer the end consumer (and other stakeholders) a clear and succinct reason for the change, then your action might fade into history along with all the other change programmes.

Table 10.1 Value-added categories

Value differentiation

In many cases, just offering the customer a review that sets out the value delivered is not sufficient. Consulting is a trade-based operation where the ability to sell products and services is a core competency. You must ensure that the closure process not only reinforces what you have delivered but shows how your services stand apart from what a competitor might have delivered. The art of the closure is in reinforcing the factors that differentiate your outcome from that of your competitors, as well as confirming what might be perceived as the commodity element of your proposition (see Figure 10.2). Value differentiation might be seen as the difference between the value of the work that you have undertaken and that which might be delivered by a comparable competitor.

Value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder and is not always an absolute element. Although value might be defined as the savings or satisfaction that the client and consumer receive from the engagement, there are many factors that drive this level of satisfaction. Consider the cost of a litre of petrol. This is a commodity that sells within a narrow price band, no matter where you might be. You might quite easily define the value of the product and equate it as being equal to the economic cost. Now switch to a different scenario – you have run out of petrol and the nearest garage is a mile down the road. How much would you be prepared to pay for the fuel now? The guess is that most people would be prepared to pay a price premium of 50 per cent to save the effort of walking further to get some more fuel. Now consider that you have run out of fuel on the way to an important client meeting. This meeting will be the final clincher in what has been a prolonged and difficult sales process and, unless you are there to close the sale there is every chance that the client will switch to a competitor. What value does a litre of fuel now hold? In cold economic terms, it can equate to a percentage of the revenue that you will receive from the client contract, which in many cases might be the price of a new car.

Figure 10.2 Differentiated delivery

So, value must be measured from the perspective of the client and consumer, not from the consultant’s perspective. Value is driven by the availability of comparable alternatives. So even if you have delivered exactly what has been specified in the contract, if the client feels that they could have achieved the result at lower cost via an alternative route, then your sense of value contribution will be minimized. In a simple world, this would not be a problem because the client’s view of the perceived value would be constant over the course of the change. However, the reality is that over the life of any change project the client’s perception of the value that you are adding could well change. By the end of the project they may be willing to pay the bill, but do so with a sense that true value has not been delivered.

Imagine you are walking down the high street and you see a shop that is selling your favourite brand of jeans at a third discount to the normal price. You decide to buy a pair and at the moment of decision you are convinced that this is a fair transaction, one where you will receive value from the purchase. However, as you walk out of the door you notice that the shop on the other side of the street also has a sale but it is offering the same jeans for half price. Your sense that the jeans were a good purchase will be immediately reduced and in many ways you might blame the shop for ripping you off.

The same can happen in one of your consulting assignments. You begin the engagement on the clear understanding that you are responsible for re-engineering one of the company’s core processes. All goes well, but at the end of the assignment the client starts to ask questions about the bad press that process re-engineering has received. They even start to question if the change was really necessary after all. Although they know in their head that you have delivered the agreed value, their heart tells them that something does not feel right and the only person they can blame is you. Here lies the quandary. From your perspective the appropriate and agreed value has been delivered, but from the client’s perspective the value is suspect.

Clearly, you cannot prevent a change in the environment or how the client sees the world, but you can have an array of arguments that will help to ensure that the client and consumer are made aware of the unique value you have offered as part of the change. These arguments can be used to help the client to realign their understanding of value, and in particular to see the value that your project has realized – even if there has been a significant change in the environment. Examples of the differentiated propositions might include the following scenarios.

- Service performance guarantees – if the client is not satisfied with the final outcome, any part of the delivery will be reworked free of charge.

- Faster delivery – your ability to mobilize resources is such that any client demands are met without delay.

- Licensed proposition – you own the rights to the intellectual capital and no other provider is able to deliver the same product.

- Trusted client relationship – the closeness of the relationship means that no other supplier is able to get close to the client.

These differentiators are crucial because they offer options that the competition might not be able to replicate. Although they are not in themselves unique, any competitor wishing to replicate the proposition will have to mobilize the necessary resources – and this takes time.

So, when an engagement is being closed it is important to ensure that the core added-value elements are communicated. But it is also important to ensure that the client understands how your particular differentiated proposition is embedded in your delivery. This reinforcement must be communicated on a logical and emotional level. The client must understand the cold logic of your differentiator, so that they are able to compare it with the competition. Second, they must feel how your service is different so that they can sell you and your ideas to others with a sense of passion. Finally, wherever possible encourage the client to touch the difference – wherever your solution has a tangible factor, ensure that the client touches, smells or feels how it is different from your competitors’ offerings. By ensuring that they understand the differentiated value there is a greater chance that the closure is successful and further repeat business can be won.

Look forward

No matter what the scenario, the best time to make a sale is the point when the customer voluntarily says how great the previous product or service has been. At this point they are happy, have found benefits from your offering and might already have made the decision to purchase again – so your sale process is simply a question of ‘What they will buy?’ rather than ‘Will they buy?’ From a commercial perspective, when this happens the cost of sale is so low as to be negligible. Logically the point on the Seven Cs life cycle where this will happen is in the Close stage.

Although this may be the logical thing to do, now be honest and think about the following:

- How many of the recent change programmes in your organization have been properly closed?

- How hard is it to get a repeat sale if you don’t know what the client thinks or feels about the current engagement?

- How many of your recent engagements have you ‘properly’ closed down?

- To what extent do you actively and consciously use the Close stage to trigger a repeat engagement?

There is plenty of evidence that both the client and consultant consistently underplay the Close stage. In many cases this is because all the effort is directed to the early stages. We all aspire to meet our new client (for potential revenue), create a relationship, understand the problem and then help to develop a sustainable solution. The trouble is that this is where it often stops – so many change programmes follow the pattern of Client, Clarify, Create, Change and runnnnnn . . . (see Figure 10.3). There is often little measurement post-implementation, and neither the client nor the consultant rush to deal with the factors that help the change to be sustainable. There is certainly an almost complete absence of an effective Close stage.

As a consultant myself I do feel bad making such audacious statements, suggesting that as an industry we are not professional and fail to take the engagement through to its logical and natural conclusion. But after running many events, seminars and client meetings where this issue is raised, I can count on one hand the number of clients who have said that I am wrong. At one consultancy conference I heard a financial director of a large company say that over the course of a year not one consultancy engagement had delivered any of the anticipated benefits. And what is worse is that all the delegates (consultants) nodded their head and agreed that it happens all the time. The failure to close an engagement effectively is one of the primary reasons for the poor brand reputation of the change industry, and will eventually lead to its destruction.

Figure 10.3 Incomplete change programme

It is the courage to build on the current engagement that is key to any successful (and profitable) client partnership. Most consultants will allocate time to find new clients and will work to promote a product or service, but this is costly and takes valuable time away from the real work. The effort needed to keep identifying new prospects can be quite draining, so the alternative approach is to focus on the development of high-value, long-term, profitable partnerships. A useful model is the Build framework, which defines the journey that an effective client–consultant partnership might follow. The framework is outlined below, together with advice on how to guide the client through the journey.

The build framework

The build process is built around three factors.

- Build dimensions – indicate how you help facilitate a desire on the part of the client to enter into a partnership relationship. Any relational process is built around three elements – the buying behaviour, an intellectual appreciation of the product and an emotional appreciation of the consultant or their product.

- Build steps – the different stages needed to progress the client from stranger to valued partner.

- Build drivers – the specific action you can take to manage each step change and so help people to move along the partnership journey.

The build dimensions

There are three primary dimensions that underpin any commercial relationship.

- Cognitive or head – what the client is thinking.

- Affective or heart – what they are feeling.

- Behaviour or hands – what they actually do.

A human being is a complex system involving an interaction between these three dimensions (see Figure 4.2). The effective consultant makes sure that they understand how all three interrelate and impact on the nature of their commercial relationship with the client. By understanding the three dimensions it is possible to build a series of actions that will help in managing the migration of a client from someone who has no interest in purchasing your services to a partner who passionately promotes you or your services to their colleagues.

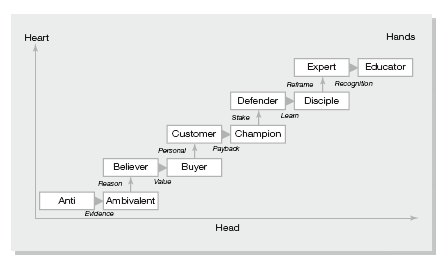

The build steps

The first time we meet a potential client it might be fair to assume that they have little desire to work with us – in many cases they might be anti the whole notion of using the services of an external agent. Certainly, the collective brand of the consultant is often seen in a very poor light. The jokes, bad press, corrupt working practices and other problems that seem to surface on a regular basis all come together to create a negative brand image. However, our goal must be to run an engagement that delivers value through sustainable change, and as a consequence move the client away from this perception and ideally help them to value our services. Over time and repeated engagements, the hope is that the client will become even more enamoured with the value that we can provide, and eventually reach a point where the relationship might be viewed as a trusted partnership – similar to that you might have with a cherished doctor or trusted financial adviser. Our goal might be to help the customer to progress effortlessly from a position where they might be fiercely opposed to the product or service, through to a position where they are a keen market advocate. So the journey might be one of a managed shift from ‘anti’ to ‘educator’ (see Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Building the relationship

However, the journey from anti to educator, albeit powerful, is rarely completed in a single step. To help the client make this shift they will often have to go through a number of steps.

- Anti to ambivalent – the client does not really have a strong belief either way.

- Ambivalent to believer – the client accepts the general need, but not necessarily for the consultant’s service.

- Believer to buyer – the client is prepared to make a single transaction purchase.

- Buyer to customer – an ongoing relationship has developed with the client.

- Customer to champion – the client will happily promote the consultant’s proposition.

- Champion to defender – the client is such a strong advocate that they will counter any criticism against the product.

- Defender to disciple – the client’s belief is such they want to learn more about the product.

- Disciple to expert – the new knowledge puts the client in a commanding position as an authority figure.

- Expert to educator – the client has the capability and desire to help others to make a similar journey.

The build drivers

These build steps offer a powerful way to categorize a client’s progression towards a partnership relationship. Although the steps do not provide a scientific or accurate portrayal of exactly what the client is thinking and feeling at any time, they offer a simple and symbolic analysis of the client and their relationship with you.

Once you understand the stages at which the client can be within the relationship, the next step might be to understand what you need to do to migrate them along the journey. How can you manage the relationship to help the move to a partnership level (if that is what you want the relationship to look like)? We do this by understanding the drivers that impact on the two dimensions of heart and head:

- What is it that we need to do to help improve how the client feels about us or our services?

- How can we help them to see the rationale for purchasing our services?

Each of the build steps is indicated below along with the driver that might be used to help the client step to the next level. Each step is also categorized as a head or heart action.

- Anti to ambivalent (head: offer evidence)

As with a consumer who is opposed to any use of the product, the first logical step may be to offer logical evidence to demonstrate that no harm will come to the client from the association with the consultant. This is generic data and not necessarily specific to the consultant’s product or idea.

- Ambivalent to believer (heart: reason to believe)

The emotional shift from ambivalent to believer is indicative that the person believes in the need for the benefits associated with the service, but has not yet bought into the need to make a purchase. The risk of getting the client to this stage is that once they believe in the need then a competitor may come along and steal them. This is why it is important not to lose sight of the next stage and ideally move the client to buyer as quickly as possible by offering firm evidence why your service offers the best value in the market.

- Believer to buyer (head: offer value)

The shift from a position where someone believes in the need for a product and actually buys the service is driven by the logical appreciation that they will derive a benefit – that there might be a financial, emotional or rational payback resulting from the cost of sale. Interestingly, although it might be that the decision to buy is driven by an emotional pull, generally the customer will be able to rationalize the decision.

- Buyer to customer (heart: make it personal)

The buyer stage can be seen as a transactional position. This is where cost will take precedence over the nature of the relationship as a buying determinant. The shift to a customer level comes once the relationship is personal. At this stage the buyer wants to come back rather than purchase from one of the competitors. Cost becomes less of a logical decision criteria – instead the nature of the relationship becomes more dominant. Research has revealed that up to 80 per cent of repeat client purchases are driven by the nature of the relationship rather than the quality of the previous project.

- Customer to champion (head: personal payback)

The logical shift from customer to champion is a subtle but important one. It is the point where the client is prepared to tell others in their organization about their experience and its value. This helps to increase market penetration and starts to reduce the cost of the sale. The customer will often make this shift because they see some form of personal payback from promoting the service. This might be in the form of brand association or political power.

- Champion to defender (heart: stakeholder)

The emotional shift from champion to defender is indicated by the willingness of the client to act as protector in cases where other people criticize the proposition. The drive for this will come from having a personal stake in the ideas associated with the offering and viewing any attack as a personal criticism of their decision to support the idea.

- Defender to disciple (head: lead through learning)

At this level the customer sees the sense in learning more about the proposition and so takes on a disciplic or committed student role. Their goal might be to acquire knowledge so they can deploy it for personal or business gain.

- Disciple to expert (heart: reframe)

The step from disciple to expert happens when the learner is able to take the ideas associated with the product and use them in a new way or direction. They do this by adding value through reframing the basic concept and presenting it to the market in a different form. At this stage they have internalized the learning and may start to present it using their own maps. This indicates immense buy-in – but the risk is if they get it wrong.

- Expert to educator (head: recognition)

The final stage from expert to educator is where the client has acquired so much expertise that they are selling the proposition to their peers. At this level the cost of the sale has almost been eliminated and the client is acting as a market advocate. There is often a need at this stage to shift the nature of the relationship from teacher or guide to that of a professional peer, where their value and expertise is openly acknowledged.

Figure 10.5 shows how the client will ideally progress up the build levels.

Figure 10.5 Build levels

Close by building

The build model is designed to help people to make choices in how they develop a successful partnership and to understand how to progress people through the various levels in the build framework – possibly to take someone who is an anti all the way through to the educator level.

However, it is rare for a client to be taken through all levels of the framework in one engagement. The ultimate goal of the build framework is to ensure that when closing the current engagement, the client is helped to understand the value that has been delivered. By helping the client understand and appreciate the value at an emotional and cognitive level it becomes possible to step the client up a level on the build model. Thus if the client started the current engagement as a buyer, then you should aspire to get them up to the customer level; if they started the existing engagement at champion level, use the project as an opportunity to migrate them to defender level. There is no optimum approach – the goal is simply to be aware of the current level, the level to which they should be migrated, and what action will help them to make the shift.

The Close stage is not the point to say goodbye – it is the point to say hello. In saying hello it makes inherent sense for the client and the consultant to reflect on their relationship and jointly decide if they want to move towards to a partnership – one that will create shared success for both parties (see Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6 Partnership build

The danger at this stage is that you might decide to use the warmth of the closure as a chance to sell a new set of services to the client. Although this might be appropriate in a few cases, the broad principle must be that taking this action will sour the relationship. If you have not re-engaged the client by this stage then it is better to walk out as a friend, and then re-enter the door at a later date with a new offering.

Time to say goodbye . . .

Interestingly one of the more common problems in consultancy, but often least considered, is just how difficult it can be to say goodbye. Like the close of a great film, the end of a song or closure of a loving relationship, they all come with a stress that is very personal, intangible and often hard to manage. It is the very fact that the emotional aspect of consultation is deemed not to be at the ‘tree-hugging’ end of the spectrum that it gets ignored or ridiculed. But consultants are human beings, working with clients who are humans and in most cases are trying to effect significant and sustainable change on a large group of people who also have human characteristics. So it behoves us to take these human characteristics seriously and in particular to explore the social nature of human beings.

These issues became very real and apparent to me after working with a team of people for over six months. We came to the point where my work was done, they were self-sufficient and we had validated that they owned the change from that point on. I remember standing in the room and experiencing a multitude of thoughts and feelings – from satisfaction in the outcome, to pride in their ability to run with the change, and finally my realization that I no longer added value when I walked into the room. Even that, in many ways, my walking into the room distracted and detracted from the process they were managing. At that point it was clear that I had hit closure and could walk away.

I then remember (embarrassingly) standing in the room repeatedly asking people if they were OK, if there was anything I could do or if they had any final questions. After this had dragged on for a while I forced myself to say goodbye and left the room. This is the critical moment that so often can prevent us from making a clear and considered exit from an engagement, instead dragging it out as yet another extended sub-project of another review process.

Thinking about what happened for me at that moment, there were three key drivers that we employed.

- Teamwork – after being part of a virtual team for so long and building levels of trust, empathy and openness, there was a huge sense of loss. At that point my role in the team was ended and my collegiate relationship with them would either die or move to a new relationship. This is driven on the basis that people, in the main, need connections with other people – hence why imprisoning people in solitary confinement is used as a powerful threat.

- Leadership – as the initial lead consultant on the team, the de faco notion was that people would listen to me – not necessarily do what I say, but it would be taken into consideration. So my sense of value and self-worth was fuelled and expanded by this temporary sense of ‘perfection’. Like an addict, it is easy to get used to, value and finally seek out this type of leadership relationship because of the deep pleasure it can bring. So the potential loss of this feeling can cause people to either try to hold on to leadership or to seek out a new one to fill the gap. This can be seen in so many ways with the unwillingness of prime ministers to realize that their time has come and it is necessary to hand over the reins to someone else.

- Care – this comes from the softer or humanistic school of consulting. The argument is that as human beings we all need to feel loved and cared for. We need to feel this as much as we need food, water and air. In the same way that we feel hungry in the absence of food, people can feel deprived when they don’t feel cared for.

The need for teamwork refers to the extent to which individuals need to have social connections and associations with others (high or low). The need for leadership refers to the extent to which individuals want to lead, influence and control others. The need for caring refers to the emotional connections with other people and the extent to which individuals seek acknowledgment, belonging, and acceptance by other people (high or low).

There is no right or wrong position on this matrix – but it can raise questions about the consultant if they have high needs on one or more of the three dimensions. If they have a high teamwork need, the risk is that the pull of the relationships and connections will make it difficult to walk away. For the consultant who has a high need to lead, direct and command, the act of walking away may leave them feeling empty and valueless. The consultant who has a high caring quotient may feel undervalued and emotionally pained from the loss of regular pats on the back from work colleagues.

There is no simple or single way to resolve these dilemmas – but there are things they can put in place to help in resolving them.

- From the outset of the engagement (the client stage) ensure that the Close stage is considered and that target dates are written in the diary. The relationship must be accepted as finite and not as a permanent connection.

- Take the time to reflect on previous closure processes to understand the personal drivers and their power – understanding what the drivers are helps the consultant to manage the unexpected feelings better.

It is all too easy to underestimate the soft stuff in a consultancy project. As the big, sexy process changes are underway – the computer screens are blinking and the bridges are being built – it is easy to ignore the softer human aspect of closure – but continual lessons from a range of projects indicate that a failure to address the closure stage properly and professionally will lead to bigger problems – ones that will come back to bite us in the longer run.