PRINCIPLE 3: APPLY THE RESOLUTION FRAMEWORK FOR DIFFICULT CONVERSATIONS (STAGE 2)

Stage 2: Having the conversation

Although we can never fully anticipate what will happen in a conversation and how we or the other person will respond, the preparation should have ensured that we have done enough to be able to focus on what is in front of us. Having prepared, we will be less likely to be worrying about information we do not have to hand or to be thinking on the spot about priorities. We will also have done some emotional groundwork.

This chapter provides the tools to build on that work during the conversation and to respond to bumps in the road that may occur during it.

It is helpful to bear in mind that the emphasis on listening and expressing our opinion, wants and needs may vary when we are having a conversation with the person we are in conflict with (and that therefore directly impacts on us) and when we are managing other people in conflict. However, the closer we are able to stick to the tools in both situations, the more likely we are able to bring balance, dignity and professionalism into the presenting situation as well as get our needs met.

Step 11: Practise expansive listening

Listening seems like a basic skill that all of us can do. However, when we are distracted by our own thoughts, feelings and agendas it can become more difficult to listen to other people. Thinking about and practising how we listen effectively can change the tone of the conversation. It can often give us access to more information or clarity about the situation which can open up options.

When we practise expansive listening, we listen with generosity and without judgement and we provide the other person with a space to be heard. Expansive listening is an art not a science. We will need to become increasingly conscious of how we use the skills and adapt them to our style or changing situations. This will take time and for some of us it is an ongoing learning process. During the course of this process, we may read the situation wrongly, lose focus or give the appearance of being judgmental. This may result in the other person withdrawing their trust or displaying emotions that we don’t know how to respond to.

In other words, we might make mistakes. In fact, I hope that you make mistakes because they will help you learn the approaches that work for you, your clients and key individuals you interact with and ones that do not. It will also mean that you are being brave in your application of the skills and use of them. Mistakes are useful because they shine a light on our practice, where it is not working or an issue that the other person is having difficulty facing up to or addressing.

The components of expansive listening are:

- empathy

- summarising and paraphrasing

- reframing

- listening behind the words

- holding the listening space

- asking the right questions.

One of the initial challenges for all of us is being willing to listen to other person’s challenges in a conflict situation. We immediately might feel that we don’t have time, that listening to other people’s troubles might bring us down, or that we might simply become irritated or bored with their attitude or what they are saying. We often do not want to admit to this as this trait does not tie in with the fact that we are good, kind and considerate people.

Nevertheless, it is quite a natural reaction, particularly when we think that we have the answer or our opinion is perhaps more valid that the other person’s. As such, again, we need to be honest about our reaction and accept that we are having it. This reminds us that we are not necessarily perfect either and then motivates us to listen with slightly more patience or compassion.

Case study

When working with a group of young people on listening skills, one of them said: ‘I don’t really want to sit and listen to other people going on about their problems – I have problems of my own.’

She didn’t show up to the next class but then came back and continued to voice her discomfort when practising the skills. At the last session, she practised her skills on a group of business people from the local area. These were people with different lives and different experiences but because she had done the course she had developed skills that enabled her to actually help these adults. She summarised the benefit of expansive listening better than I could ever hope to when, at the end of the course she said: ‘I realised that listening to other people can make me understand that if I can help other people I can help myself. Through that I have found confidence and am able to speak to people without being aggressive.’

This example illustrates clearly that when we really listen to someone else’s challenges it can help to give us clarity on challenges in our own lives and be an equal to that other person whatever our age or social status. Particularly at the beginning, practising expansive listening may feel like it is taking a long time, we can make mistakes and become frustrated. We need to keep in mind that mistakes and frustrations will serve to improve our practice and insight and, in most cases, we will be able to come back from them successfully.

Empathy has already been discussed in the last chapter under Step 8. There is no doubt that it is tricky to practise empathy with someone who we are in conflict with when they are standing in front of us. However, the preparation will help us to start the process of exercising empathy much the same as we might exercise a muscle. The more we practise and exercise, the more natural it becomes to do it. The techniques below should help to keep us in the frame of being empathetic and make it easier to practise empathy as we truly hear the other person.

Summarising and paraphrasing

Summarising and paraphrasing techniques help us to:

- reflect back to the other person what we have heard

- check that we have understood what the other person has said

- let the other person know we are prioritising listening to them.

When we paraphrase, we present back to the person what they have been talking about, acting as a verbal mirror. Here is an example:

| SPEAKER: | I haven’t been sleeping and I have been up every night worrying about what my neighbour is going to do next. | |

| LISTENER: | So you are having sleepless nights worrying about what your neighbour is going to do next? | |

| SPEAKER: | Yes, I am really worried that they are going to do something stupid like tear down the fence. | |

| LISTENER: | So you are concerned that they might tear down the fence? | |

| SPEAKER: | Yes, or something else. I don’t know what they are capable of, they could do anything. | |

| LISTENER: | So, you are not really sure what they might do? It could be anything? |

At first, it can feel uncomfortable to paraphrase. We can feel as if we are mimicking what the other person has said. This discomfort is generally the only barrier to paraphrasing well. However, when we do it, we often observe a sense of relief coming over the other person that they have had a chance to tell someone what is going on for them and confirm that they have been heard.

Paraphrasing forces the listener to focus solely on the content of what people are telling us and repeating or reflecting back what we have heard. This grounds us in what the other person is actually saying as opposed to what we may be assuming they are saying. It also gives us an opportunity to play back what we are hearing.

In doing this, we are not necessarily agreeing with the other person or telling them that they are right. Rather, that we have fully heard and understood what they are saying. When we do this, the other person will generally either expand on what we have summarised, clarify any misunderstanding they think we may have, or feel they have been heard and move on to what they need to talk about next.

When we summarise, we repeat back aspects of what the person has said using fewer words but not changing the nature of what they have said. We pick out key themes and use key words from what the person has said.

When we use summaries, as with paraphrasing we need to be prepared for the fact that we have misunderstood what the other person has said, or may have said, whether by implication or fact. To check that we are correctly reflecting what the other person has said, we may preface our summary by saying something like: ‘Correct me if I am wrong but you seem to be saying…’ or ‘What I am hearing is you think XYZ – have I understood that correctly?’ Even when we hear something a certain way, it may not be what the other person is saying, and in order to summarise and paraphrase correctly, we need to be open to the fact that we may have misunderstood the individual.

Equally, when we hear what we say through someone else, it can sound different to the way we normally hear ourselves. So, you may summarise or paraphrase word for word what someone has said and they may come back and say that you have misunderstood them. Initially, we might see this as having made a mistake. However, the speaker may hear what they have said played back to them through you and realise that although this was their initial reaction, on reflection this is not what they want to be saying or indeed thinking. Whether this is because they have not expressed themselves in a way that reflects their true or c or that they

may have onsidered thoughts or you have misunderstood is not important. If we have summarised or paraphrased in a way that does not seem true or resonate with the speaker, we can always recover using the same skills. Here is an example.

| SPEAKER: | Anne has a history of being difficult and stopping people getting on with the job. I’m just her next victim. | |

| LISTENER: | So you feel that Anne has stopped you getting on with your job? | |

| SPEAKER: | No, but I think she will do. |

In this case, the recovery will be saying something that shows you have now understood:

| LISTENER: | So you think that she will stop you getting on with your job in the future? |

What is important is that the listening allows the individual to express themselves, help themselves clarify their thoughts and feel heard. If they challenge what you have said or change it, it means that the reflection has been valuable and served its purpose.

Sometimes it is hard to distinguish what is summarising and what is paraphrasing and there will inevitably be some crossover. The table below gives a picture of the distinction between the two techniques.

The listener needs to be careful about how they summarise and paraphrase. When people are talking about us or an organisation that we are associated with and are on some level championing or responsible for, the first thing we want to do is respond and put our point of view forward in order to defend ourselves or the organisation. Also, we may try to structure our summaries so that blame does not fall on us and the other person sees our point of view. In these situations, it will be really important to:

- be aware that we will want to defend and justify ourselves

- choose our words carefully so that our paraphrasing and summarising are as neutral as possible

- be prepared to adjust our summaries and paraphrases where they veer towards being argumentative or attempts at self-justification.

When we are a party to the conflict, we should always remind ourselves that we will have an opportunity to respond later, but the first step is to truly practise expansive listening to get the full measure of the other person’s perspective.

It is very easy in these situations to infer judgement so we need to find ways to make sure our summaries do not do that. So instead of saying, ‘You say I think you are doing a bad job,’ you might reflect back with ‘You are saying that you think that I think you are doing a bad job.’ In this way, we demonstrate a respect for the other person’s point of view without may to agree with it. We also avoid creating any perception of judgement which may cause the other person to feel unsafe about setting out their perspective because they are not being heard. This in turn can lead to a shutdown in all or part of the communication which can escalate the conflict again.

Reframing

When we reframe, we effectively summarise or paraphrase in a way that puts a different frame or light on the situation.

| SPEAKER: | This has gone on for too long. I don’t want to go on like this any longer. | |

| LISTENER: | So you really want this to stop and for things to change and be different? |

The speaker has not said that they want a change or things to be different, but has said that they don’t want things to continue as they are. The listener has inferred from the speaker’s somewhat disempowered statement that they want a change and so reframes the more disempowered statement into an empowered one in which the listener might be able to do something about the situation. There is no doubt that the listener’s judgement or preferences play a part in the reframing and we need to be careful of forcing rose-tinted glasses on the speaker. Having said this, the speaker will generally let us know if the reframe does not reflect what they are really saying, either by actively disagreeing with what we have said or shutting down and not talking as openly or at all. Again, we can amend our summary, paraphrasing or reframing to reflect the corrections that the speaker has made.

There is a concern that when we listen in this way we might lose what we might need to say to the other person, particularly if we want to explain or justify ourselves. However, if we have prepared in line with Stage 1 in Chapter 6, we can always revert to this and know that we will be able to bring these points up at a later stage. At the same time, listening may mean that we change our initial perspective and are able to move through or let go of some of our original points, concerns or issues and focus on what is most important to us.

When we are listening in this way, we should also avoid questions other than an opener such as ‘So tell me what is going on for you’ or ‘Do you want to talk about what has been happening/causing you concern?’ By avoiding questions, we allow people to tell the story and emphasise what is important to them as opposed to what is important to us on the basis of the question we have asked.

Listening behind the words

Listening behind the words means getting underneath what the person is saying. We can do this in a variety of ways:

- Noticing their body language – whether their legs and arms are crossed or they are sweating.

- Listening to important or maybe painful information that they seem to skip over or laugh about when it appears very serious.

- Gently noticing what we feel as they are talking – sometimes the feelings that are triggered in us can reflect their feelings.

We can reflect back the non-verbal communication that we notice as part of our summaries or paraphrasing. When we do this, it is important to acknowledge that it is our experience of what they are saying or how they seem to us.

In this way, we once again leave the door open for the other person to clarify any misunderstandings. For example, ‘When you were talking about that situation you rolled your eyes and I am sensing you were frustrated or irritated by what the other person did.’

Hold the listening space

Often the benefits of expansive listening will come through the ability of the listener to be comfortable with silence. This involves waiting for the speaker to find their words and to take the time to formulate their thoughts and get to the bottom of them.

Generally, we only have to wait for a few seconds to give the person a chance to think about what they are saying or add something that they were reluctant to talk about. Again, this can open up the conversation, increase trust and allow for a more honest communication. It can help the other person believe that we are not just listening in order to respond but listening because we are open to hear what is being said.

It can be challenging to control ourselves for those few seconds to allow a bit of space into the conversation, but try it a few times and see how it can change the direction of the conversations in ways we don’t always expect.

The more we practise these elements of expansive listening, the more instinctive it becomes and the more successful it can be. The success of expansive listening will be evidenced by a recognition that the person we are listening to feels heard, starts to hear themselves and thinks about and builds upon creative options.

You might like to practise expansive listening. Follow the parameters above and write down how you felt.

What did you sense from the other person in terms of what they felt and thought?

Where did you find ourself judging the other person?

What happened when you allowed for silences?

Step 12: Practise expansive questioning

If we are practising expansive listening, the need for questions reduces as the speaker hears back through the listener what they are saying and answers the obvious questions that have come out of what they have said.

The danger in using questions is that we can use them to direct the speaker’s focus towards our assumptions and agendas. So they need to be used with care. Having said that, questions are a great tool for clarifying issues both for the speaker and listener and opening up the options.

The aim of expansive questioning is to facilitate a solution rather than fix a problem. An expansive question will open up the conversation, encourage reflection, elaboration, dialogue and deliberation. Expansive questioning requires us to know that even if we think we know the answer we may not and that the range of answers we may receive are limitless.

Even if we have an impulse to fix, if we can monitor the way we use questions we can translate that impulse into a successful facilitation. All too easily our questions bely our opinions and judgements and can shut down the listener’s ability to look to themselves for the solution. So, we need to actively and consciously use open questions to facilitate the speaker.

Generally, we use open questions to open up the conversation and closed questions to drill down on the detail of the response. Simply put, a closed question requests a yes or no answer and an open question does not. But, beyond this, we must remember that the most effective question is one which we do not assume we know the answer to or that does not blame. Instead, we consciously use questions which facilitate the speaker to dig deep and find the whole solution to the problem rather than the limited solution which we as listener can see.

Open questions

The following open questions open up the conversation:

What would you like to talk about?

What do you mean by …?

What would you like me or your colleagues to do about that?

Is there anything else you think we should talk about?

Bear in mind some key questions in coming to a solution are those that you will have already asked of yourself:

What do you want?

What does that look like?

How far are you/we from achieving that?

What do you/we need to do to get you there?

Closed questions

It is also helpful to be mindful of the sometimes less helpful closed questions that can only be answered with a yes, no or one word answer that risk cutting off the conversation:

Do you/I?

Is it/are you?

Can you/I?

Do you want me to go ahead with that?

Checking questions

These are often (but not always) closed in nature but help to continue rapport when summarising and reflecting back. They also give the other person an opportunity to clarify what they mean.

Can I check that …

How does that sound so far?

Is that your understanding?

Have I got that right?

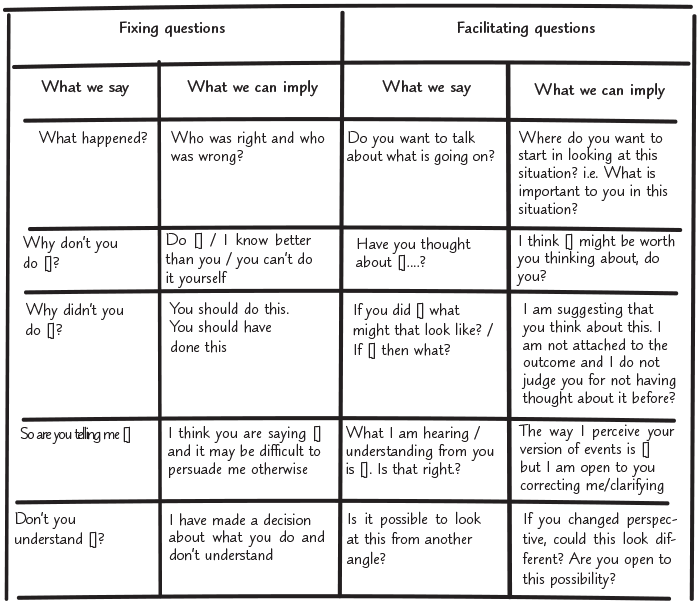

Expansive questions, also focus on facilitating, as opposed to fixing, in the following way

You can practise expansive listening and questioning in the following way:

- Use a very open expansive question to start off the conversation.

- Engage in expansive listening by avoiding questions for at least the first five minutes.

- Before asking the question check what judgements you have – what you think the answer should be.

- Try converting opinions you have like ‘Why don’t you do this?’ into an expansive question like ‘Have you thought about doing this?’ or ‘Do you want to tell me more about your thoughts about this?’

- Check in with yourself by asking yourself if you are leading the person in a certain direction or you are trying to manipulate them to do something.

- Always return to expansive listening in response to the answers to your questions.

- If you get stuck, think about asking the question ‘What do you want?’ or ‘Shall we focus back on what you said you want?’

Step 13: Negotiate

Having prepared for the negotiation, you will have a clear idea of your top and bottom lines and of what is most important to you and what may be important to the other person. You will also have an idea of the key issues and those that you may be more willing to let go of. These need to be clearly front of mind.

We also need to make conscious choices about our strategy and approach. If we are practising all the suggestions, we might find that the nature or the emphasis of the negotiation changes. For example, we may reach agreement on certain issues, additional issues may come up, our fellow negotiator may not react as we expect and our perspective may also change. Accordingly, we need to remain lithe during the course of the negotiation and be aware of our options in terms of negotiation style and strategy as they develop.

Prioritise principles over personalities

The aim in a negotiation is generally to get what you want. Allowing the behaviours of the other person (personalities) to distract us in that process can lose us the opportunity to achieve that.

We can compromise getting what we really want (principles) when we get caught up in our irritation over the other person’s behaviour. We lose sight of the principles we are pursuing by getting enmeshed with personality issues. This can cause us to react to the other person rather than pursue our goals and work through the negotiation.

Choose your negotiation strategy

We can tend to adopt a negotiation strategy without considering whether it is the best strategy for the situation. We can also find ourselves responding to the other person’s strategy unconsciously and not necessarily in the best interests of the negotiations. So, it is helpful to understand what negotiation strategies we and the other person may consciously or subconsciously be using and continue to evaluate their effectiveness during the course of the negotiation.

Here are some common strategies.

Haggling

When we haggle, we negotiate much as we might when buying or selling on a market stall. One person might start proposing a high figure, the other person will respond with a low figure and they will trade figures until they land on a relatively random point somewhere in the middle that they can, generally reluctantly, agree on.

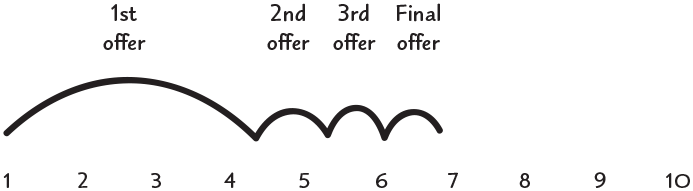

If you adopt this approach, you need to consider your offers carefully bearing in mind that people are generally prepared to make one big leap from 1 (first offer) to 4 or 5 (1st offer), followed by a maximum of 3 or 4 further negotiated adjustments arriving at say 6 or as our final position. On this basis, if you are negotiating a random trade, ensure that your first offer takes into account the distance the person might need to travel to arrive at a negotiated agreement.

- It recognises that an agreement can be reached without agreeing that either party is right or wrong.

- It gets the negotiation moving.

- It clarifies the range.

- It recognises the random nature of the risk of continuing the conflict.

And the cons:

- It’s difficult to logically justify the agreed result.

- There is a danger of being or feeling out of control.

- There is a danger of alienating your negotiating partner by putting in an unrealistic figure.

‘Who blinks first’

‘Who blinks first’ is the strategy where we try to get the other person to make an offer in the hope that what they offer is slightly better than what we were prepared to agree on. It means that we don’t have to expose our hand but it can be a gamble as to who breaks first.

The pros of this strategy:

- It clarifies the other person’s expectations.

- It provides a starting point for negotiations.

And the cons:

- You may expose a willingness to settle on better terms than they are willing to offer.

- You may expose a gap between you and your counterpart that requires substantial further negotiation.

Watch my lips

Some negotiators will go in with one figure or position and be clear that they are not prepared to move from this. However, with a little testing, movement is sometimes possible but the approach makes it clear that there is very little room for movement.

- You are clear on your position and can appear strong.

- Your counterpart may feel that they have to accept your terms for fear that agreement won’t be reached otherwise.

And the cons:

- You may appear intransigent to the other people and unwilling to negotiate.

- You may sabotage the opportunity to negotiate within the grey areas.

Seeking the win–win

Through achieving a deep understanding, not just of the other person’s negotiating position but the reason why they want what they say they want, allows us to create a possibility for a win–win solution.

In order to do this, we are well served by keeping to the following core principles based on Getting to Yes Published by Penguin Random House:

- Focus less on who is right and who is wrong and more on areas of common interests and needs. This means moving away from blame and retribution, which can be hard to let go of. Instead, it involves concentrating on what we both might want and need and, flowing from that, what might work for both of us. It can be summed up simply by the choice ‘Do you want to be right or do you want to be happy?’

- Prioritise the generation of creative ideas and options. Key to the generation of these creative ideas and options will be the use of expansive listening and questioning. Also crucially if all parties can commit to this priority, the flow of these ideas and the possibility for play and creative solutions that we have already discussed, open up. However, even if one person allows for expansive listening, the opportunities to generate these ideas and options grow.

- Work together to establish an objective ‘norm’. Often the reason we are in a conflict in the first place is that we are applying different standards. It is often difficult for one party to simply agree to the other party’s standards. One party might expect the other to start a meeting at 8am, the other party may have worked until 11pm and thinks that 10am is a fair start time. In these circumstances, both parties can look for objective norms: what other people have done, what has happened in similar situations, what experts would say. This may include what other people in the office do or people in other offices do. It may involve speaking to an independent professional or expert or looking at what people have done in the past. The more collaborative the search for these criteria is, the easier they will be to agree instead of them becoming a bone of contention in and of themselves.

These principles are based on Principled Negotiation®, developed at the Harvard Negotiation Project and set out in the book Getting to Yes by Roger Fisher and William Ury (plus Bruce Patton for the second edition).

Identify and manage negotiation styles

The Thomas-Kilmann conflict model instrument sets out five overall ways we negotiate. We all have preferred styles that we slip into by way of habit but we can adjust these styles by consciously choosing the best style for the presenting situation. Also, the more familiar we are with negotiating styles, the easier it will be to identify the approach taken by the other party in the negotiation and to work with their style in order to best achieve our goals.

The negotiation style is different from the negotiation strategy. A negotiation strategy includes the practicalities of what we want to achieve and how we are going to achieve it. The Resolution Framework Part 1 set out earlier includes a negotiation strategy which includes looking at top and bottom lines and the process and tactics we will need to achieve them. Part of our strategy will centre around choosing the style of negotiation we wish to adopt to ensure that it is the most effective in the circumstances. When choosing our negotiation style we will balance using a style that is most natural to us with one that is most appropriate for the circumstances. A strategic negotiator will ask themselves:

- Would it be helpful for me to go out of my comfort zone?

- If my negotiation style hasn’t been working, is there another alternative?

- Is it better to adopt a style which is most comfortable for me?

Our negotiation style is led by and belies our motivations. These will run on a scale of ‘concern for me or us’ which triggers a desire to cooperate and, on the other hand, a concern for results which moves us to want to win by asserting ourselves and our needs. According to the Thomas-Kilmann conflict mode instrument, the five key negotiating styles are accommodating, avoiding, competing, compromising and collaborating. (See the website for more details: www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki.)

Accommodating

This is the approach which leads us to co-operate with the other person without necessarily asserting our own needs. We may do this to display generosity, when we feel we have done something wrong and need to make amends. We may do this when we need to keep the status quo or when we can see that the matters in hand are more important than our own wants and needs. There is a difference between acceding to someone else’s needs because we want to and doing it because we feel we have to. In the latter situation, we can feel that we are not getting anything back and develop resentments which are destructive to ourselves and to the relationship. To avoid this scenario, we need to check our motives and take responsibility for our decisions to ensure that we do not fall victim to this decision.

Case study

Freddie was a manager at a small charity and shared many of the projects with Sarah. Sarah had small children and would often come in late or have to leave early or last minute and asked Freddie to cover for her. At first Freddie was happy to help out but he started to feel taken advantage of. He also started to talk about Sarah to colleagues asking them whether they thought the job was too much for her.

Sensing there was a problem, Sarah asked Freddie if there was anything wrong. This gave him an opportunity to say that he felt slightly taken for granted. Sarah realised that she had not shown him the appreciation she felt towards him. They both realised that when Freddie did not feel like covering for Sarah he could say ‘Not today’. Sarah also recognised that she needed to do more to help out Freddie when she could.

How can you get the most out of someone who is accommodating?

Asking someone who is accommodating what they need can go far to turn around a situation. Together with this, showing a level of appreciation of any compromises they have made can be particularly effective especially when the accommodating behaviour has created a degree of resentment.

Avoiding

When we are avoiding, we don’t co-operate with the other person and we don’t assert our needs. It can be helpful to avoid situations that we don’t feel able to address or which would be better dealt with by someone else (manager, adviser). However, while nothing is being done about the situation, the situation is unlikely to change and the avoidance can leave people feeling uncertain and unheard.

Case study

Jane was director at a pharmaceutical company. Emma reported to her and they had worked well together for ten years. Emma had been a loyal employee who had outperformed on her targets year on year. When Emma’s father fell ill, Emma started to miss targets. Jane felt that her mind wasn’t really on the job and that Emma was not performing in client meetings. Jane was concerned that they might lose one of their most important clients who Emma had previously been responsible for. Jane brought in another individual to work with the client and emailed Emma to tell her. Emma asked to set up a meeting to talk about it. Jane said that she would set the meeting up but was too busy at that time. Jane also postponed a few subsequent performance review meetings. Emma kept on trying to speak to Jane and set up meetings with her but the more she tried the more unavailable Jane became.

After many years of loyal service, Emma decided to get a new job. Jane tried to change Emma’s mind at this stage but Emma said it was too late.

How can you get the most out of someone who is avoiding?

When someone avoids, we can gently but persistently invite them to engage with us. This is different to sustained and insistent demands. Rather, it lets the person know that it is important to us to engage with them about this but respects their boundaries. Alternatively, or as a fall-back approach where we have tried but failed to engage, we may need to accept that they do not want to address or talk about an issue and work with around that.

Competing

Competing is an assertive but uncooperative approach to a conflict situation. We can adopt a competing approach because we want to stand up for what we believe in or to get the job done. It is also an effective approach in an emergency when people need to act decisively. However, a competitive approach can erode the team or community because it marginalises voices or opinions in attempting to achieve the best result. As a result, even the most well-intentioned competing person may end up being or feeling alienated or misunderstood albeit they achieve the result they had originally intended.

Case study

Jimmy was part of a group of five long leaseholders who all lived in separate flats in a Victorian house. He was also a co-director (along with the other leaseholder) and treasurer of the freehold company which owned the leases on the property. Generally, the other leaseholders had let Jimmy manage the property and make payments as and when they needed to for renovations of the property.

Recently, one of the freeholders, Faisal, had had an accident in his flat which had resulted in carbon monoxide being released into the building. Nobody was injured but there was significant damage caused to the roof.

Jimmy sent Faisal a letter saying that he needed to pay for the full renovation of the property or his lease would be forfeited. He did this without consulting his fellow directors of the freehold company. Faisal’s lawyers responded and Faisal confronted a number of the leaseholders. The majority of the leaseholders were very upset at having to be drawn into the situation and confronted Jimmy at a directors’ meeting. Jimmy responded by being confrontational and aggresive towards the other freeholders as he felt that he had acted for them in their best interests when they ‘couldn’t be bothered to do anything themselves’. As a result, the other residents stopped talking to Jimmy and Faisal, factions formed and arguments went on for several months about who was going to pay for the repairs of the property.

How do you get the most out of someone who is competing?

A competitive person can seem like a bulldozer and we can presume that they are hell-bent on getting what they want no matter what. Often, they will be doing this because they think that they have the solution or that they are best placed to deal with a situation.

If we ask someone who is competing what their motives are, we can start to understand why they are taking the action they are taking. This will also allow the competing person to think about what they are doing and demonstrate that they do not necessarily need to tackle the situation alone. Equally, it is helpful to assertively but carefully let the competing person know what our views and commitment to them are.

Compromising

Compromising sits in the middle ground of all the responses. The aim of somebody who is compromising will be to find a solution that will partially satisfy all those involved. The advantage is that some solution is reached and some of the issues, wants or needs are addressed. As a result, it is likely that everyone involved achieves some wins. Compromising can also address issues in a short timeframe without going into too much detail or disruption.

Compromising can be a useful step back from competing and accommodating as we will see. However, compromising will only ever address the surface issues without providing the opportunity to explore the issue in depth.

Case study

Joel was a property investor and Sandy was an interior designer and project manager. They had worked together for many years. Sandy agreed to renovate Joel’s property for a fee of £50,000 which Sandy had reduced from £70,000. This was because Joel had promised that he had a very big commercial project coming up that he was going to use Sandy for. The only condition for involvement in the commercial project was that Sandy had to complete Joel’s property by June.

During the project, additional work was carried out. Sandy’s final bill to Joel was £60,000. Joel asked Sandy for receipts for artisan building work which Sandy did not provide. Joel then said that the works were not finished and required further work which Sandy organised. Joel eventually moved in in September.

As a result of a financial negotiation between their lawyers, Joel agreed to pay Sandy £20,000 but refused to pay the balance because he said that ‘Sandy had been sitting on her hands’. He also said that he had proof that she was working on another job while she should have been working on his job. Finally, he alleged that her boyfriend had done most of the work instead of the artisan builder Sandy had promised. Joel suggested that they sit down for a coffee and talk about it. Sandy said that she did not want to discuss it because she couldn’t believe that Joel had thought that of her. She just wanted to ‘get her money and move on’. That being said, she privately acknowledged that Joel’s accusations had some truth to them.

After a set of fractious email exchanges, Joel eventually paid Sandy an additional £35,000 as a final payment. Sandy stopped getting work from people who Joel had previously referred to her and did not get any more work directly from Joel. Eventually, her business which was based on referrals became no longer viable.

Although a compromise agreement was reached, Joel said that he thought that if Sandy had been willing to have a collaborative conversation with him, it is possible that the working relationship may have been salvaged even if she had been guilty of the things that Joel suspected.

How can you get the best out of people who compromise?

It is helpful to identify and acknowledge the compromising person’s priorities – speed, avoidance of in-depth discussion – and any other priorities that are also important to you. Once you have done that you can explain that addressing those issues are also a priority for you. If you can simplify them and present them in bite-sized chunks, you may be in a better position to encourage the compromising person to address them.

Collaborating

Collaborating is an assertive and co-operative approach and is at the opposite end of the scale to avoiding a situation. When we collaborate, we enter into in-depth discussions and negotiations to explore the other parties’ position, interests and needs as well as clarify our own. The focus of the collaborating parties is on finding a solution that fully meets the needs of those involved.

Collaborating is particularly valuable when a comprehensive solution is required and there are very few, if any, areas which can be compromised upon. It is also particularly useful where those involved need to learn and understand each other or solve a problem through understanding several perspectives. Collaboration can also work to explore the feelings that have been involved in the breakdown of the relationship as well as the facts.

The benefit of collaboration is that the process of exploring the issues in depth and building consensus builds commitment to the solution. In this way, agreements reached are likely to be more sustainable because the parties have worked for and achieved a buy-in to the solution.

Case study

Anthony and Matt had built up a bakery business that had been running successfully for the past 15 years. Anthony had always been very hands-on and Matt had been responsible for the finances. As the business grew, Matt brought in his wife Julie to help run the business. At the time Anthony happily agreed as Julie had been director of finance at a nationwide bakery chain.

Julie and Anthony had a number of small disagreements over the course of the initial months of her tenure. Julie felt that Anthony made irresponsible and ill-thought through purchasing decisions. She also raised concerns about health and safety issues in the bakery and told Anthony that she thought that the day-to-day running of the bakery was shambolic. Anthony said that Julie just wanted to ‘splash cash’ didn’t realise that it was a much smaller operation than the company she previously worked for and she was being dangerously extravagant. When Julie showed Anthony her workings and future plans and projections for the bakery, Anthony said that she was patronising and went to Matt telling him that he wanted to sell his half of the business.

Through a collaborative conversation, Anthony established the following:

- Julie had great experience but his experience was that she was putting him down.

- He didn’t understand how the business finances worked so he avoided spending money.

- He knew the bakery needed better financial and operational management.

- He had valuable talents in product and business development.

- He was scared that Julie and Matt were going to try to kick him out of the business.

Julie established the following:

- She had not acknowledged Anthony’s previous good work and creative talents.

- She was really keen to get involved in what felt like a great opportunity for her.

- She had been over-zealous about introducing new systems and introducing very corporate systems into a small but growing business.

Matt established the following:

- He wanted a new challenge and to exit the day-to-day running of the business.

- He had not worked through with Anthony or Julie the implications of the changes being put in place.

- He wanted to support the business but he wanted to move into a backseat role.

Following a series of collaborative conversations, Julie and Anthony established their mutual passion for the business and Julie started to demonstrate that she could relieve Anthony of some operational stress. Anthony also felt more heard and appreciated and was able to free up some head space to start to concentrate on new product development and potential strategic opportunities. Once this happened, Julie and Anthony were able to have constructive and creative conversations about the business. From there, they agreed to formally define their roles and consider and agree some concrete plans for future growth including changes in management and structure.

Matt and Anthony realised that although their business relationship had been successful it had changed and it was time for Anthony to be less involved in the business. They acknowledged that they had had an inspirational business relationship which needed to evolve. They agreed that Matt would retain a position as board director while pursuing other interests. They also agreed to have a monthly catch-up breakfast in which they talked about business ideas and what was going on for them so that they could continue to benefit from each other’s advice, support and inspiration without necessarily working closely in business together.

Step 14: Follow up

Once the negotiation is completed, we tend to want to walk away from it and expect both sides to follow through on what they have promised. However, we need to allow for the fact that the follow-through may hit bumps in the road. We may revert to old behaviours, we may forget to follow through or we may simply be unable to deliver on our promises.

This can create a new set of resentments and conflicts very easily, particularly due to the added expectation that the matter was to be resolved. So, it is helpful to plan for these bumps in the road with agreed follow-ups with respect to certain actions and to anticipate how the parties may work together and communicate to resolve the situation should things not go according to plan in the future.

In cases where a transaction is easily completed following a negotiation, the follow-up can be very straightforward and may extend to an email confirming that something has happened – money has been paid for example. However, if the negotiation has involved an ongoing relationship, it may be helpful to plan times for follow-ups, establish what will be covered and when and prepare in a similar way to the initial negotiation.

Equally, if the result of the negotiation is for actions to be taken that are dependent on other people, an agreed set of dates for follow-up or notifications of key actions can avoid the need to re-engage in the conflict. For example, in the case of an agreement between neighbours about the removal of a dead tree, an agreed follow-up plan may include:

- notification that the local council has been contacted (within a certain period)

- confirmation that the council had received the request and details of their timetable

- notification of approval by the council

- notice of the date of removal of the tree

- a date for follow-up in case of delay more than six months from the date of the negotiation.