MEDIATION: WHAT IT IS AND WHY IT WORKS

Throughout this book, I refer to mediation even though most of the content will provide solutions that pre-empt the need for it. Why? Because the tools and principles used in the mediation process can equally be applied to situations in which the conflict has not escalated or when two parties are at loggerheads. It is the principles of mediation that enable resolution and that will form the basis of the seven principles.

The principles of mediation and why they matter

Mediation is a voluntary, confidential process in which an impartial third party supports the parties to come to a solution that works for them without giving advice or opinions. Between 70% and 90% of mediations are successfully concluded, indicating that it is an effective way to resolve disputes.

In a formal mediation, the appointed mediator will hold the principles as sacrosanct as they are the fundamental elements of the process that the two parties buy in to and take responsibility for. They are also the keys that establish the trust and independence of the mediator – crucial to support the parties as they reach an effective resolution. The mediator will be the guardian of these principals in the mediation process.

In informal mediation settings, using mediation principles are extremely helpful and the closer they are kept to, the more likely a meaningful resolution will be achieved. However, it is not always that easy to keep to them, partly due to other factors in play and partly to the experience of the informal mediator, conflict coach or ‘resolution agent’.

The role and boundaries of the informal mediator, conflict coach or resolution agent and how they are managed is fully explained in Chapters 8 and 9 in Principles 4 and 5. For example, when we informally mediate an issue between colleagues, we may feel an allegiance to the company and be concerned that we will feel or be compelled to disclose certain issues as opposed to being able to adhere to strict principles of confidentiality. Or an individual may feel that they are obliged to go to an informal mediation, as opposed to going to it voluntarily, as otherwise they may be seen to be obstructive.

Equally, the informal mediator may want to influence the parties to take a decision because they think it is the right one or one that represents their interests. It will be a balancing act that will require the informal mediator to apply the principles imperfectly and hopefully ask for help if they are struggling. Having said that, the principles adopted in formal mediation should be regarded by anyone in the middle of a dispute as standards to reach for and that achieve exceptional results.

The voluntary nature of the process means that it is necessary to come to the table and engage in the resolution process in some way. Whether that choice is because the individual feels that they have no other choice or whether they are choosing to take some constructive steps towards resolving the situation does not necessarily matter. Neither does that choice have to be a whole-hearted or happy one. The degree of commitment to that choice may, however, affect the quality of negotiations.

Often, when we do something because we have to, we can feel that we had no choice and therefore don’t need to take responsibility for what happens. We move into a more child-like state of mind in which we subconsciously put the person who is making us do something in the role of punishing parent and we find ourselves acting out a child-like set of behaviours. Our level of commitment reduces as does our ability to drive the process and make good powerful decisions.

If I turn up at a mediation because somebody has forced me to, then I immediately feel a victim and my level of commitment to the outcome will probably be reduced. I am most likely to rebel against the process and the outcome as something that was not my choice. I will feel justified in my rebellion because I was coerced and may become disruptive as a way to take control of the situation.

It helps to look at the behaviour of young people in this type of situation as their behaviour can highlight in a more exaggerated way our more vulnerable and child-like instincts and reactions. We will explore this in Chapter 5 Principle 2: Take control of your response.

Case study

While writing this book I was working with a group of young people who had been identified as having child protection issues. Although they were pretty tough, they were also vulnerable. I was teaching them personal conflict coaching as a leadership skill. In particular, the course illustrated and modelled how they could become constructive leaders and that their experience could benefit others when they were able to turn the obstacles of conflict into opportunities.

We were considering their natural responses to conflict. During this process, I put the following scenario to them: A teacher puts you in detention unfairly for something you haven’t done. Do you:

- do the detention anyway?

- not show up at the detention?

- show up at the detention but say you don’t think it is fair?

- ask to speak to the teacher about why they put them in detention and to present the case?

- try to disrupt the class?

The overwhelming majority of the young people said that they would try to disrupt the class. When I asked them why, they said they had received the punishment anyway so they might as well commit the crime.

This illustrated very clearly to me that even though I may show up, as long as I feel forced or like a victim, or to some extent powerless, I will feel justified to act in a disruptive manner until such time as I choose to engage in the process.

Being volunteers in the process, we are already geared to make a series of choices and decisions that we can become empowered through. Choices will include:

- If I do not attempt to resolve this, what will I or the other person do next?

- What is important to me?

- What decisions do I need to make?

- Am I prepared to compromise?

- Am I prepared to think about compromising?

Even before the mediation, the process allows the individual to stop and think about the situation they are in and reawaken them to their choices. By requiring someone to volunteer to mediate (or decide not to), they are making a conscious decision about the way they want the situation to progress and, in so doing, put themselves back into the driving seat of that situation. The result is that they are also more likely to have to buy in to any decision or action resulting from that process and deliver solutions that may have not been previously thought of.

Confidentiality is probably the most powerful element in the mediation process and in resolving conflict generally. Specifically, this confidentiality will apply to individual conversations between the mediator and the individual parties.

To preserve confidentiality, the mediator must do the following:

- Explain and guarantee that they will not disclose any information that has been given to them in private meetings without individual authorisation from the parties.

- Double-check whether the parties feel comfortable that conversations with the mediator will be kept confidential.

- Obtain specific authorisation to disclose information if the party who owns the information decides that they want to disclose it.

- Ensure that only the exact information that the party agreed to disclose is actually disclosed – by writing that information down, reading it back and confirming again that it can be disclosed.

- Ensure that separate meeting rooms of all the parties are sound-proofed to the degree that each party cannot hear what is being said by the other.

- Set clear boundaries so that confidence is not broken by, for example, the mediator inferring certain information from one party that they have been told by the other party.

- Include a provision in the mediation agreement that is signed with the parties to keep confidentiality.

- Not disclose any information with respect to the mediation to third parties, in particular the names of parties or their companies if relevant.

Confidentiality provides an opportunity for communication to open up. It allows some freedom for people to say what they think to an independent third party without fear of it being disclosed or of being caught out by it. With the protective cover of confidentiality, individuals start to feel more comfortable about owning or taking responsibility for their part in what has happened without fear of being misunderstood or punished. They can also play with alternative scenarios without having to commit to anything, including amending their bottom-line position. In this way, the reality of what is happening or true, as opposed to the fear of what could happen, can be addressed.

In creating a confidential environment, sensitive information can be discussed and considered, as opposed to being covered up and ignored. It creates space for that information to be considered and strategies to be thought through to address the consequences of that information.

Case study

Jo and Sam went to university together and a few years later Sam asked Jo to invest in his business PROPCO and make some introductions to potential additional investors. They had agreed that Jo would earn a commission on any investment that the business received as a result of the introductions he made. Sam didn’t pay Jo on one of these deals and Jo threatened to take Sam to court. Jo also suspected that there were other deals that he had entered into where Sam should have paid him a commission but hadn’t. Jo also wanted to make sure that Sam would pay commissions to him in the future.

During confidential discussions between a mediator and Jo, it became clear that PROPCO was not making any money and was in danger of closing. Sam acknowledged to the mediator that he should indeed have paid commission on the deal as Jo had suspected but clarified that there had been no other undisclosed deals. However, he also told the mediator that he had some but not all the money he owed to Jo and could not pay him in full. Sam was trying to close a deal with one of the companies that Jo had introduced him to and if he did then he would be able to pay him. However, if that company knew what a precarious position the business was in, he was worried it would not invest.

During further confidential discussions between the mediator and Jo, Jo said that he did not want to take Sam to court and simply wanted to get his money back and know the truth.

Following the discussions with the mediator and having taken legal advice, Jo told Sam what he had told the mediator. The confidential discussion with the mediator gave Sam an opportunity to rethink the situation and work out what the risks and options were before presenting key information to Jo.

Although disclosing this truth was embarrassing and a potential risk for Sam, it allowed for a conversation that was rooted in reality. This in turn resulted in Sam and Jo agreeing a plan for Jo to help Sam close the deal with the investor and for Sam to be more open and clear with Jo about what was going on in the business.

Confidentiality was only one part of the reason that a resolution was reached but it was important. It allowed Sam to be honest and find a workable solution with Jo that could form the basis for them to work together for their mutual benefit.

Mediation is a process with a clear structure and the mediator is simply the vehicle to execute the process. This is important because making it about the process, rather than the mediator, keeps the focus on the parties and the issues. Often, we hand over all responsibility to advisers and then are disappointed in the result. The mediation process allows us to get back in the driving seat and use advisers to their best advantage without handing over our lives to them. This serves as a win–win for both client and adviser.

Key elements of the mediation process are set out in Part 3 of this book.

The requirement for an independent third party who does not give advice or opinions can seem counter-intuitive, but it is essential to obtaining a sustainable solution. The mediator will never know as much about the situation as the respective parties, or even their advisers, and therefore will never be able to see all the angles. By not limiting the process to what the mediator may or may not know, the following becomes possible:

- The solution is not limited by the mediator’s knowledge or lack thereof.

- The mediator does not become invested in their own proposed solution.

- The mediator can focus on what might be possible.

- The parties can start to open up ‘out-of-the-box’ solutions without the limitations of complying or getting things right.

- The mediator can reflect back on the bigger picture including mutual priorities, interests and needs.

Litigation, mediation and other forms of alternative dispute resolution

Although this book focusses on mediation, it is one of a number of forms of what is known as ‘alternative dispute resolution’. This is a term applied to forms of dispute resolution that serve as an alternative to litigation or, in other words, going to court. These will include arbitration, conciliation, mediation, negotiations between lawyers and simple face-to-face negotiation.

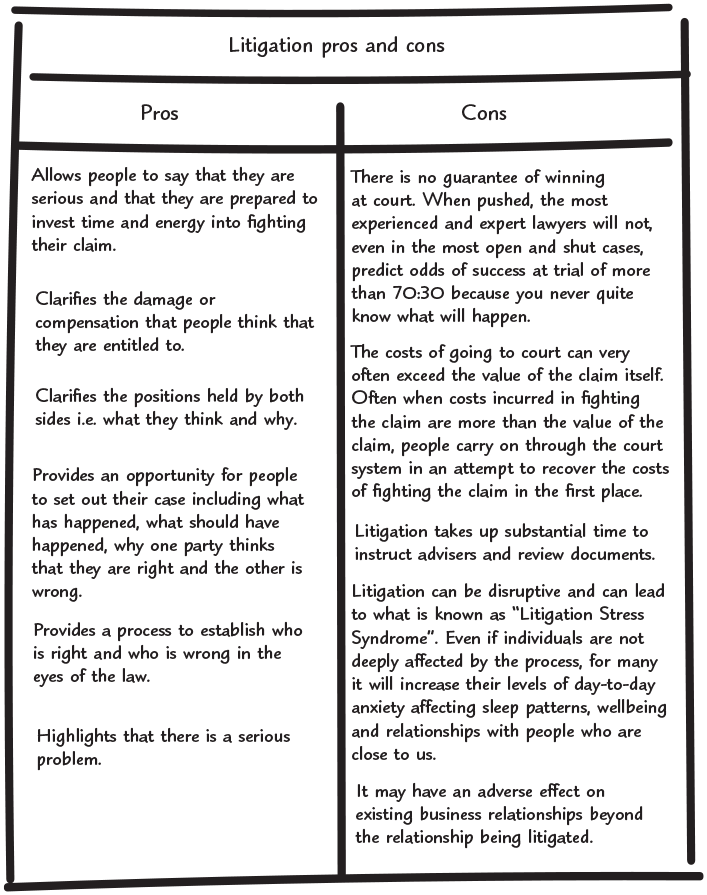

Litigation

Litigation is the action of bringing or being involved in a law suit. It covers situations in which one person takes the other to court, which will also include for the purposes of this book to a tribunal. The most effective use of litigation is in cases where a judgement absolutely needs to be reached with respect to a point of law. The action of starting litigation can be the trigger to explore and move to some of the alternative forms of dispute resolution.

If you are thinking about litigation you will need to:

- be clear about your case: who did what to whom and when

- be prepared to back up your case with evidence (letters, bank statements, contracts) as the stronger your written evidence, the stronger your case will be

- consider taking legal advice and engaging a lawyer

- be prepared to ask other people to get involved as witnesses

- establish whether you have any insurance in place that you can use to pursue or defend the case

- know how much money you have available to pursue or defend the case

- know that even if somebody did something you think was morally wrong, it may not be wrong in law

- think about alternative forms of resolving the dispute.

If you are thinking about mediation before litigation, bear in mind that the other person will need to agree to go to mediation – the mediator will not make them go to mediation for you. You may want to take legal advice and carry out a mini risk-analysis with respect to the following:

- what your best and worst-case scenarios might be if you go to court

- what the likely cost of going to court may be

- how much time it might take to pursue the matter in court

- what your chances of success might be

- your top and bottom lines if you are to enter into an agreement

- how to make sure that the agreement at mediation is kept to e.g. a formal written agreement drafted by your lawyer.

Bear in mind that it is very unlikely that your lawyer will be able to give you a definitive answer with respect to these questions as things change. Even ‘open and shut’ cases can be complicated by new information. However, your adviser will help you to analyse the risks and benefits. Even if you do go ahead with litigation, these questions will be useful to return to and review during the process so that you are clear about the risks and benefits of decisions you make during the course of the court process.

Mediation is often proposed or suggested by the parties before litigation or when litigation is in progress. The threat of litigation can focus the parties’ minds on resolution because of the risks involved and because it encourages an efficient timeframe. Current processes are geared towards winning and therefore escalating the conflict. This is because by continually trying to ‘get one over’ the other person we alienate ourselves from that person on a personal level and we become the opponent. Early intervention, including mediation, is an opportunity to stop the clock and climb off the conflict escalator.

Litigation, or the threat of it, is not necessary for mediation to happen. In fact, mediation can happen at any time and can take various forms from formal to informal. This is because it is a process that helps people to get whatever it is they want out of a conflict situation with another person. That might be money, justice as they understand it, an opportunity to rebuild a working or neighbourly relationship, or an agreement about ending a relationship. It is different from a court process that focusses on a decision being made that requires one person to be right and one person to be wrong on the basis of a set of core standards.

Both processes are important. Sometimes it is important for someone to be proven right or wrong and for wrongdoings to have consequences. Sometimes we need to define and construct our own sense of what justice looks like and create that justice.

Arbitration

Arbitration is a process in which disputes can be resolved outside court and is less formal than court. Unlike a judge who will base their decisions on law, the arbitrator may take into account other factors allowing for a fuller discussion of the issues that may go beyond legal rights and wrongs. The arbitrator will, however, come to a decision or an award which the parties agree to be bound by.

Conciliation

Conciliation is similar to mediation although generally used only for employment disputes. The conciliator plays a similar role to the mediator but will be more likely to put forward a proposal for settlement – unlike mediation where the mediator is not involved in the process of settlement itself. Also, if the party has legal representation, the conciliator may liaise only with that representative and not with the individual.

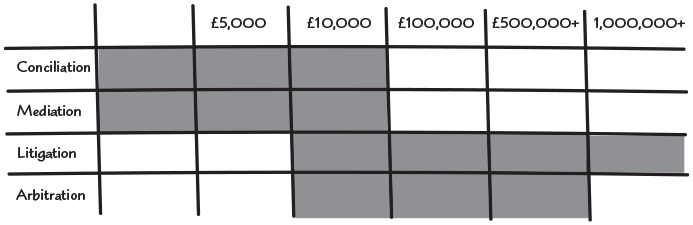

Costs of dispute resolution

The costs of dispute resolution vary according to:

- when the process of resolution starts

- the value of the claim in question

- the complexity of the dispute

- the route taken to resolve the dispute

- where the dispute resolution takes place.

The table below sets down an example of the range of costs involved in dispute resolution in the UK.

It is worth bearing in mind that the fees referred to in the litigation column above may also be incurred when going to conciliation, mediation or arbitration in addition to the cost of that intervention.